Davey Davis's Blog, page 11

February 3, 2024

David Davis: Members Only

I’ve never needed stitches, other than for my transsexual surgeries (see above). I’ve never cut my finger too deep, never broken a bone, never been hospitalized for anything that wasn’t first scheduled by an administrator. All the recreational suturing I’ve received has been over virgin skin or a hole I already have. Daemonumx calls one of these latter procedures the “bellybuttonectomy,” and she’s given me at least three.

January 23, 2024

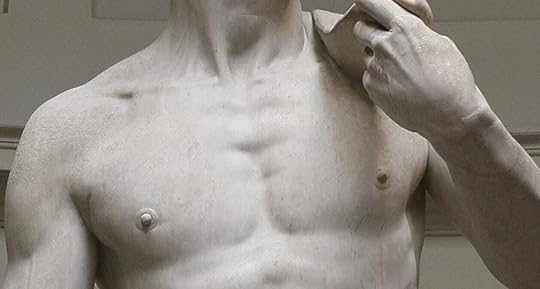

David Davis

I don’t think of myself as a slut. I’m always surprised when I’m referred to as one, whether it’s with the recognition of a fellow traveler, or within a context where it is, theoretically, only a fantasy, or even as an attempted insult. These days, to be called a slut gives me something of an anthropological pause, a gentle but insistent sense of disidentification: Me? A slut? <Staring off into the sunset> You really think so?

I’m not denying my lifestyle or quibbling over my body count. It’s just that slut doesn’t feel like me. I mean no disrespect the proud sluts in my life, and I’m certainly not arguing against my more-than-reasonable inclusion among their ranks. But over the years, slut has acquired an insufficiency, an obsolescence. Changes to my gender, pop feminism, and queer social mores are all in there, to be sure, but it seems like something else is going on.

Of course, masculine women are not sluts the way normal women are. When I was younger, I often found myself in situations—parties, book fairs, demos—where I was, if not unwelcome, then at least assumed to be unable to relate to the fears and frustrations of life as a slut. I was ashamed of the emotions stirred up by what were usually oversights, and mostly kept them to myself: I’m fem in my own way! I may not look it, but I was once a girl, too! Rapists don’t care how pretty you are! These encounters made me feel lonely among comrades. They made me feel undesirable, though the cash in my pocket said otherwise. They made me feel as if a lie that had long been told about me had been suddenly retracted, without apology, before I could even begin to deny, much less reclaim, it.

Last weekend, I went to a party where feet penetrated holes, bound dykes dangled over the floorboards, and someone was ridden like a pony over big-gauged knee piercings. (Unfortunately, this last scene happened after we left, so I can only enjoy it via social media.)

I love parties like this. At their best, they both distill and amplify the feeling you get when you share a sad story with someone who can laugh at, rather than look away from, its cruel absurdity. It’s brave to accept pain, but I think it may be braver to share it with someone else or to witness it for them, especially if you care about each other. I knew most of the people in attendance, but even if I hadn’t, I would still have felt like I belonged there. When I looked around me, I was puzzled by the notion that we could be violent1. Violent, in that context, feels as foreign to me as slut does.

I don’t remember hearing slut (or seeing it written on someone’s body in ink or blood) that night, but I’m sure it was there, one of the many handy tools of negotiated sexual degradation between friends.

Most mornings, the first thing I do when I wake up is tidy my apartment. This extension of my meditation practice relaxes me, and builds anticipation for the first treat of my day: a hot cup of drip coffee, black.

I count as an accomplishment the fact that I can now do my tidying, most mornings, without aural distraction: no TV, no Democracy Now!, not even Schumann, who is the artist I listen to the most, according to Spotify2. It gives me the space to not think, which is naturally one of the best ways to foster thoughtfulness. This morning, while doing dishes, it occurred to me that it’s been five months since I’ve had sex with a stranger. That last stranger has since become a lover, so for our purposes he doesn’t count, pushing the timeline back even further.

Do I feel the need to correct this? I wondered, rinsing a preferred porcelain mug. Yes, but not strongly enough to act upon it right now.

It feels unnatural for me to not be available—up for it, ready and willing, submissive and breedable, etc.—in that way. I have been a slut, by all common definition, for many years, perhaps my whole life, at least according to the people who raised me. It’s the story, often sad but often not, that I have always known about myself, and it makes me uncomfortable when I can’t see myself in it. In the parlance of SSRI adverts, I don’t feel like myself. I wonder if this could be a good thing.

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

I have been following the coverage (or lack thereof) of Columbia University’s use of chemical weapons on students protesting the Palestinian genocide. There are too many worthy places to direct our attention at this time, but for anyone looking for more evidence of how these foreign atrocities affect “us” “here”: these students (who are consumers, by the way, paying to attend this institution [when is the customer wrong?]) have been assaulted with chemical weapons used by the Israel Defense Forces against Palestinians and which American police departments have acquired from them in the past. Even if all you care about is your own safety, the relationship between the IDF and the American military/police, funded by our tax dollars, should galvanize you.

1Even “kinky” straight people are like this, yet more evidence that “kink” and “leather” are not the same thing.

2Couldn’t tell you a single thing about him or his music but here we are.

January 19, 2024

David Davis 45, part 1

Do you remember your first sex scene? Was it in a book, a film, or another kind of media? To my surprise, the first that came to mind for me didn’t include sexual intercourse at all.

I was 7 or 8 years old. While flipping channels with my sisters, I accidentally landed on Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. In the “sex scene” in question, an ultra-racist standout from Spielberg’s 1984 blockbuster, our hero, Indy (Harrison Ford), witnesses a ritual human sacrifice that culminates with the removal of a still-beating heart from a captive’s body. I remember fire and drums, the bloody penetration of one man by another, and the gruesome certainty that I had stumbled across an unspeakable evil of Biblical proportions.

But not even my horror was a match for my remorse: I knew my dad and his wife would punish me for watching even just a few minutes of this grownup movie without permission. I wanted desperately to confess, to be reassured with fact (Don’t worry, it’s all pretend!1) and forgiveness, but to do so would first mean getting in trouble. My agonizing only lasted a few minutes, I’m sure, but after what seemed like hours, I finally came clean.

It turned out that my parents didn’t care about what I had done, certainly not enough to punish me for it. They were amused by my histrionics—and I can understand why, now that I’m an adult myself. I don’t remember what happened after that.

My immediate association of an occult, Orientalist cannibalism with sex comes as no surprise for an Evangelical child raised by racist anti-intellectuals whose primary values, shame and work ethic, were cherrypicked from religious pig-ignorance and right-wing propaganda. I was a particularly guilt-ridden kid, obsessed with the potential for transgression, all of which felt sexual to me, because as I understood it the sexual was the greatest taboo of all. Violence was one thing; I remember, at around the same time as the above anecdote, my dad explaining to me over dinner that capital punishment didn’t violate the sixth Commandment, that in fact Jesus Himself would have been, in a way, too primitive to understand why Americans needed the leeway to put some people in the electric chair2. Sex, on the other hand, was unforgivable.

When I ask, Do you remember your first sex scene?, I want you to be as free-associative about it as I was because, 90 years after the Motion Picture Production Code and 150 after the first Comstock law, the distinctions between art, commerce, and moral and legal obscenity—all of which dictate both sex and scene—remain unclear. How is a sex scene more or less sexual because of the gender(s), races, and sexual identities of its performers (both as actors and characters)? Because of the medium and genre in which it’s found? Because of where and when and by whom it was made? When does a sex scene cross over into pornography (and by framing this question in this way, do I limit us with a false spectrum, a careless conflation of genre or form, or something else)?

The sex scene is neither discrete nor contained. Like all sex(uality) it is constructed, disciplined, and often punished. This makes it a perfect site from which to explore the leaky, smushy, capaciousness of fantasy, desire, and profanity; to share and discuss our favorite sex scenes; to analyze texts across media; to investigate our horniness and disgust; to elevate our discussions of art to something more interesting than, Does consuming this make me a good person? Does creating that make me a bad person?

More to come soon. I’m excited for this one!

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

1These are people who regarded The Exorcist (1973) as a docudrama, so the odds were not in my favor.

2I was taught that “Thou shalt not kill” was the sixth Commandment, but I’m discovering that it’s ranked differently in other Christian traditions. In any case, my dad is a bad person.

January 12, 2024

David Davis

You can set a sundial by it: 6–12 weeks after something bad happened, my body will take a vacation from functioning correctly. Like Kafka’s bug man, I will awaken one morning in a state of anxiety that slowly, excruciatingly clarifies into a realization that something is wrong.

Nowadays, my autoimmunity flares are usually mild, and with a little effort—rest, medication, a depressingly bland diet—my symptoms will disperse. Some joint pain and an upset stomach aren’t so bad, not when compared with the years of my life when they were at their worst, a fever pitch of suffering that prevented me from holding down jobs, staying awake in class, even regulating my body temperature. And yet somehow, these reminders are worse than the pain they hearken back to. How could that life ever have been worthwhile? I wonder, indulging in the coward’s rhetoric. If that were true, even a little, I wouldn’t have worked so hard to stay alive.

In “On Risk and Solitude”—found in On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored: Psychoanalytic Essays on the Unexamined Life—Adam Phillips writes movingly and persuasively about the developmental importance of risk-taking. For the adolescent, the pursuit of risk is an exercise in “fearless passivity,” a surrender of the self that echoes the dependence of infancy while simultaneously striving to differentiate itself from it. In risk-taking, he suggests, the adolescent is communicating the questions that his infant self might have asked of the mother, had he the capacity.

It is not that the adolescent is attempting to “own his body”…as part of his separation from the mother, nor is he simply taking over her caregiving aspects. He is testing the representations of the body acquired through early experience. Is it a safe house? Is it reliable? Does it have other allegiances? What does it promise, and why does it refuse?1

With this essay, Phillips challenges the historical pathologization of risk-taking in psychoanalytic literature, speculating as to what we might call the “positive” reasons for so-called sexual perversions: perhaps, he says, these perversions are a way of keeping alive the risk-taking part of the self, the “fearless passive” who “both knows and refuses to know” that there comes a point in treatment (/in our lives) when we must do the thing we most fear.

“We create risk,” Phillips writes, “when we endanger something we value.” Perhaps risk-taking is also the reverse-engineering of being alive. I’m endangered, therefore I am; I’m entrusting myself to the unknown, therefore I have something to protect.

Over these past four years of DAVID, I’ve written a lot about risk: emotional, sexual, artistic, interpersonal; the risks of having an identity, of heavy S/M, of dyke cruising. I’m on the record regarding risk’s potential role in a good life as I understand it, but I’ve never felt unconflicted on this point. It is easy to assume responsibility for everything, to find every fault within oneself, and in so doing to use risk not as enrichment, but as avoidance, depersonalization, abandonment. In this way, we engage in the fantasy of control, and fantasies, as we know, are characterized by their impossibility. A fantasy can never come true.

Naturally, Phillips has plenty to say about that, too: compulsive risk-taking is “always constituted by a fantasy of what has already been lost—only the impossible, as we know, is addictive.” Reading this, I was reminded of the epigraph I included in my first novel, by the French writer Robert Pinget: “When you’re expecting bad news you have to be prepared for it a long time ahead so that when the telegram comes you can already pronounce the syllables in your mouth before opening it.”

I love control and I hate control, a contradiction for which I have often castigated myself. By way of psychoanalysis, a discipline about which I still know very little, Phillips suggests the possibility of understanding this as something other than a paradox. He ends another essay, the luminous “First Hates: Phobias in Theory,” with these words: “the aim of psychoanalysis is not to cure people but to show them that there is nothing wrong with them.”

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

1Bolding mine.

January 3, 2024

David Davis: Members Only

That’s Lily, Terry says. At our knees, a morose old dog gazes up and a little to the side, as required by canine politesse.

Hi, Lily. I add prosody to my voice for her benefit, but I don’t offer my hand for her to smell. Though I like dogs, I’m afraid of most of them.

Come on in, says Terry. He has the kind of smile that people call toothy: big, friendly, imperfectly impressive. He’s wearing blue sweats and a grey hoodie. Lily, of course, isn’t wearing anything, not even a collar. I follow them down the long, narrow hallway.

The apartment is very gay, which sets me at ease. Playbills with bottle-necked chanteuses, flyers with slogans and pink triangles, a Target rainbow or two. Even when I’ve fled his apartment in anger, a gay guy has never made me feel endangered. Not yet, anyway.

Terry sits on the couch. Although our messages had been terse and transactional, I heed an instinct and climb onto his lap.

December 29, 2023

David Davis

This is not a review of Poor Things (2023), which I hated. These are just some notes, with errors and misrememberings and things like that. Sorry if I got anything wrong. I don’t super care.

Willem Dafoe’s Godwin is Frankenstein and Emma Stone’s Bella is his monster. God resurrected beautiful Bella’s dead body, along with the brain she was pregnant with when she jumped off a bridge. Born again Bella is a big baby who must re-learn how to walk, speak, and reason—a “lovely r- - - - -,” in the words of Ramy Youssef’s Max, God’s pathetic assistant. (I will be talking about ableism shortly, but the use of this word not what makes Poor Things uniquely ableist1.)

In any case, Poor Things reassures us that Bella is not a r- - - - -. As her doctor daddy observes, her physical and intellectual development happens at an astonishing clip. As Bella becomes someone who can speak in full sentences, walk on her own, and masturbate with round fruit (??), she is granted the dignities accorded to real persons: after she violently resists God’s assignation of Max as her husband, her father gives her permission to go off on a sex vacation with bad-boy buffoon, Duncan Wedderburn (Mark Ruffalo, always good for a comic turn).

With Bella’s journey, Poor Things reveals itself to be both bildungsroman and picaresque2. Together with Duncan, she travels the world and discovers the joys of fucking, the evils of capitalism, the suffocation of polite society, the tedium of sex work, and the pleasures of autonomy, which as we know are rare for any woman, especially one with a mind of her own3. After a lot of adventures and cool full frontal4, Bella returns home for God’s deathbed and her marriage to Max, which is interrupted at the last minute by Alfie, her first brain’s husband, an evil man who almost succeeds in castrating her5. Luckily, spirited Bella gets the better of him. She goes back home to Max, watches God die in his own bed, and, in a heartwarming turn of events, decides to carry on her father’s important work as a grave-robbing baby re-animator6 (??).

The final scene of Poor Things includes at least three of God’s Frankensteins. There is Bella, her successor, Felicity (Margaret Qualley), and Alfie, who was for some reason not murdered, as he should have been, but instead kidnapped and brainswapped with a goat. Felicity is not a prodigy like Bella; Alfie is ruminating on the lawn. Ha ha! Unlike Bella, they are stupid.

My beef with Poor Things isn’t in the delight it takes in the behavior of stupid people, or not exactly. As much as it disgusts me, the use of people with intellectual or cognitive disability as props and punchlines is not exceptional, in cinema or elsewhere. But such low-hanging fruit becomes hypocritical in a film that fancies itself a feminist hero’s journey. After insisting on her own sexual agency, having a political awakening7, and doing sex work, through which she encounters gay sex and socialism through another worker, Toinette (Suzy Bemba), Bella makes her treacly return home to enter adulthood via heterosexual marriage, an estate big enough to require servants, and the continuation of her father’s legacy as, again, a grave-robbing baby re-animator.

As we can see from Bella’s happy ending, her experiences have shaped her—and rattled the men around her—without really disrupting the balance of power. Which is fine. Not everyone is a freedom fighter. Most of us are just out here living our lives. (And I think it’s neat, and not nothing, that Poor Things permits Bella to be a prostitute that rejects shame or censure.)

But ultimately, the class consciousness garnered on Bella’s perverted adventures doesn’t really take her anywhere; it tempts us with socialist whoredom, but not any socialist behavior, by her or any other whores. Her return to God’s luscious steampunk manse is triumphant but empty: Toinette has dumped prostitution and Capital to join Bella in perpetuating God’s legacy; Max, the guy who thought fucking a two-week old in Emma Stone’s body was sexy, will assist; the maid who cares for Felicity is served a drink on a tray, an empty signal of equalization that doesn’t negate her status as proletariat; and Alfie, who has been sentenced to the life of a r- - - - -, as Max might put it, for his vicious brutality, lows or brays or whatever it is that goats do.

I hated Poor Things because I felt condescended to. Its bawdy grotesqueries, its sex and violence, are merely shocking or titillating, rather than interesting. In its transgression for the NPR crowd, it’s giving self-serious Barbie (2023), with (somehow) more baby talk, or, as I said on Twitter, girlpower Forrest Gump. I don’t think Barbie was a better movie, but if I had to choose to watch one of the two again, I’d pick the doll—and I hated Barbie, too.

If my claim that a movie with such lively action is boring seems disingenuous to you, I’m sorry. It’s just that Poor Things insists that the nothing it has to say is something, and a progressive something like that. But in the bygone tradition of the Grand Tour, Bella’s hero’s journey—from which she returns changed, but ready to embrace more of the same—lacks emotional resonance. It’s little more than prolonged slumming, shot with a fisheye lens.

See you in the New Year! Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

1Although I do think it’s an interesting screenwriting choice, given that this kind of language (mental retardation, etc.) did not come into popular usage until the mid-twentieth century, which is, I think, notable in a Wes Anderson-esque steampunk that seems to situate itself as Victorian—that is, in the nineteenth century. Pay attention to anachronism; it is not random.

It just occurred to me that this film is based on a novel, so the use of “r- - - - -” may be carried over from the original text. I’ll never know, because I shan’t read it. Nevertheless, it’s still a choice.

2Is that a thing? Sorry if not.

3Even if it is actually her baby’s mind.

4I’m not being sarcastic. I love when movies don’t treat sex scenes like plutonium.

5I mean this in a sort of Freudian sense, but also in a literal one, because Alfie wants to cut her clit off in order to curb her promiscuity. I think I’m remembering correctly that the Victorian steampunk doctor he hires uses the acronym “FGM,” which is hilarious to me. Anachronism is not random, but it is sometimes really stupid!

6I just realized that Bella’s first name was Victoria. Victor Frankenstein…Victorian England…anyway.

7Bella discovers the existence of an ambiguous global underclass, to which she tries and fails to give some money before sort of moving on. Knowing they’re there is all the growth that’s needed, I guess.

December 26, 2023

David Davis 44, part 4

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 of my series on Method acting—what it is, and what it isn’t.

Most of My Dinner with Andre (1981) takes place at Café des Artistes in New York City, where Wally (Wallace Shawn) eats dinner with his old friend, Andre (André Gregory). Over the course of their meal, the two men share a long, meandering conversation about art, spirituality, and finding meaning, which is initiated when Andre tells Wally about recently hitting a wall as an acting teacher. I had nothing left to say, he explains. I didn’t know anything. I couldn’t teach anything. Exercises meant nothing to me anymore.

But, Andre goes on, he was convinced to take on a group of students in a remote Polish forest inhabited by only wild boars and a hermit. Though there was a language barrier (the Polish students didn’t speak English and Andre didn’t speak Polish), his students were chosen because they, too, were questioning the theater. Together, the Doubting Thomases do improv, as they would in any other workshop, with one important difference, as Andre explains:

Except that in this type of improvisation, the kind we did in Poland, the theme is oneself. So, you follow the same law of improvisation, which is that you do whatever your impulse, as the character, tells you to do, but in this case, you are the character. So there's no imaginary situation to hide behind, and there's no other person to hide behind. What you're doing, in fact, is you're asking those same questions that Stanislavsky said the actor should constantly ask himself as a character: Who am I? Why am I here? Where do I come from, and where am I going? But instead of applying them to a role, you apply them to yourself.

The purpose of Andre’s workshop is learning how to play again. I would define play, a habit or skill that many of us must work to develop as adults, as feeling and acting extemporaneously upon sensation and desire. A willingness to play produces a feedback loop of self-esteem: play engenders self-confidence that, when exercised, nourishes the creative, innately curious, pro-social mechanism of play. The cycle continues from there.

How is play different from art? I would say that art is play disciplined; that art is play at work, perhaps.

I was reminded of Andre and Wally’s exchange by a recent interview with the French actor Isabelle Huppert. “When Huppert takes on a role,” writes The New Yorker’s Rebecca Mead:

“…she enters it as if arriving in a new country without having read a guidebook, alert to its strangeness and fascinated by its distinctiveness. ‘Sometimes I read these interviews with actors who say they prepare, and they imagine the characters’ background, and family, and where they come from,’ [Huppert] told me. ‘Well, it’s not my way of doing it. To begin with, I don’t believe in the idea of playing a character. I just believe in the idea of playing states—joy, sadness, laughter, listening, talking. That’s all I think about. In order to have the fiction come through you, you have to get rid of the idea of a character. The character is like a prison. And you could go further in that way of thinking—since it’s not a character I don’t need to know anything about her.’”

Huppert makes no specific claims about the Method here, but its muddled shadow looms so large over the past century of screen and stage that I think it’s safe to say they’re in conversation. With this tension in mind, Huppert’s approach could be seen as diametrically opposed to common misconceptions of the Method, which was of course developed by the Stanislavksi mentioned by Andre. If Stanislavski’s Method is thinking, then Huppert’s is embodied.

But I think of Stanislavski’s system, the infamous Method, as something akin to meditation. As yoga prepares the body for the stillness of meditation, the Method prepares the actor for the embodiment of acting. From this perspective, Huppert is not opting out of this process, because she never needed it. She always knew how to play.

See you in the New Year! Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

December 14, 2023

David Davis: Members Only

With one exception, I haven’t been monogamous with my romantic partners since my first gay relationship in my early twenties. That one exception was a compromise with disaster: in the latter half of the same decade, I very smartly agreed to monogamy with a woman who loved to violate the terms of our non-monogamy.

You’ll be shocked to learn that trashing my values only gave her more opportunities to cheat, which she preferred to do in the shittiest ways possible.

December 7, 2023

Your favorite DAVIDs of 2023

I can count the number of DAVID-driven hate emails I’ve received on one hand, but they’ve left their mark. Last spring, a number-and-symbol address sent a message that was mostly gibberish, save the solitary legible, if inexplicable, statement: You have gonorrhea! Yet within the week, my doctor confirmed that I did, indeed, have the social disease. I felt seen, if nothing else.

Luckily for me, most of you are able to see me in a much friendlier way. Over the past almost-four years, DAVID has continued to grow and change, and aside from the occasional evil clairvoyant, almost everyone has been super nice about it. So, thank you for being here, truly. Thank you for subscribing, sharing, responding, and supporting me in other ways, like buying my books. Your money helps me pay off my student loans and your participation fuels the tragic feedback loop that is my desperate need for attention. I couldn’t do it without you.

Read on for the top 10 DAVIDs of 2024.

This essay about my first heavy bondage/abandonment scene isn’t just the top DAVID of the year, but of all time, supplanting my 2020 piece on bad dads. It turns out you guys love it when I suffer for no good reason. Fuck you very much.

When would I know that it was time to panic, that he wasn’t coming back? Four hours? More? What was my worst-case scenario? Through the slit below my chin, the sunlight had begun to fail. How long would it take before I had to piss myself? How long before I felt the torture of thirst? Of course, all of that would only happen if something tragic befell my friend, like a car accident. I imagined him on the sidewalk in front of his apartment, unable to enter because of a police barricade or clouds of smoke. How selfish I am, I thought, worrying about his misfortune or death because it would mean that I would be stuck here, afraid and suffering, and not for his own sake.

what is the trans experience without trans people?

A transphobic encounter while promoting my second novel, X, came to represent a nascent desire to make art about transness in a different way. This resulted in my third novel, Casanova 20: or, Hot World (forthcoming in 202?!), which you’ll also find excerpted behind the paywall.

I enjoyed researching this essay about sleeping with cis men as much as I enjoyed writing it.

That cis men of all orientations lie to themselves in order to have sex with me is nothing new. I used to think I could predict the nature of these lies based on the liar telling them: some straight men think of me as a girl, some gay men think of me as a boy, and some bi men think of me as the best of both worlds, as they’re inclined to put it. What I’ve learned since going on hormones is that not only are these lies unpredictable, they’re often not even internally consistent.

Fat needles. Fainting. Femme tops. Nuff said.

Most of the time, the needles go in my back, where I can’t see them. I tell people it’s because I’m squeamish, which is true. Last night, when Daemonumx was suturing and piercing me amidst others doing similar—pussies were sewn shut; hand-sketched designs came to florid life under painstaking scalpels—I kept my eyes averted. I’m already prone to fainting as it is.

I wrote about one of 2023’s standout queer discourses, the fall of Lex, and Make the Golf Course a Public Sex Forest!

As the punchline it’s come to be, Lex encapsulates the limitations imposed on those of us who can’t access the freedom of public sex in the same way that (some) cis men can. I’m like super open to pushback on this, but I suspect that this is why you can have a Grindr and not a Grinda; that is, a lesbian sex app that is explicitly about fucking, rather than about dating, relationships, networking, and, implicitly, monogamy in which any capital exchange happens behind the plausible deniability of a marriage contract. It’s one thing to pony up the overhead for such an apparatus. It’s another to execute the kind of backend enforcement required to manage any risk of solicitation to an extent that satisfies stockholders, VC funds, credit card companies, and the feds that it could be a safe bet.

As the world degrades, knowing what emotional regulation is, and how to do it, is only going to become more important. This one’s at the intersections of family, ableism, and PSTD.

Over the past few years, as we’ve belatedly learned about things like PTSD and the parasympathetic nervous system, C’s behavior has begun to make sense to us. It’s not that she was being set off by nothing for all this time—it’s that we, her caretakers, didn’t recognize her triggers for what they were. It wasn’t that what we interpreted as violence was a symptom of willfulness or malice—it’s that the overwhelm of sensory stimuli and trauma response made it difficult, even impossible, for her to do anything other than scream, cry, and hit. She was not bad, as we had been telling her, and each other, for her whole life. We were not making her life safe enough for her to ever be good.

Every once in a while, I get a little squirrelly on the topic of writing for money.

Only gradually have I realized that my favorite question—Are you a writer?—is a somewhat sadistic one. Curious about people but for the most part too nervous for most normal socializing, I’ve learned, in a sort of instinctual way, that putting someone on their guard is a great way to control the conversation. Any good interviewer knows that simply giving their subject enough rope is likely to be more successful than even the most incisive line of inquiry. Gently prompt someone to account for something they feel even a little conflicted about and nine times out of ten you can sit back, relax, and let their neuroses carry you away.

if I didn’t hurt myself so much, then I wouldn’t hurt so much

We call it RACK, or “risk-aware consensual kink” for a reason: sometimes your shit gets wrecked.

What began as a meditation on incest fantasies became a portrait of one very special trick.

When Pony Brad arrived for our first session, the other girl and I took care of business, then brought him to the Green Room. Pony Brad pointed at me and said, “You’re my aunt,” and at the other girl and said, “and you’re my sister.” Straightforward enough. So far, so good. Time to put on the old razzle-dazzle and make out with a bitch I lowkey despised while pretending that we were all related.

I think this one is kind of sexy! Which reminds me: I need to write about writing sex. Look forward to that series, along with others about masculine socialization, dreams, sex scenes, feeling, and John Gielgud, in 2024.

See you in the New Year! Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

December 3, 2023

David Davis 44, part 3

You know, there was a film being shown by this Black lesbian club on the Columbia campus and they put up signs that said, “no Jews allowed.” And as someone who plays a lesbian journalist on The Morning Show, I am more offended by it as a lesbian than I am as a Jew, to be honest with you.

—Actor Julianna Margulies

A few months ago, I began a series about how common misconceptions about Method acting inform the ways we understand not just films and plays, but the (bad) behavior of the artists who create them. I used Jonathon Majors and Tom Cruise to begin exploring how these misconceptions are cynically leveraged by industry agents, lawyers, and executives to reinforce any definition of art or authenticity that align them with capital—to the point that an artist’s violent interpersonal behavior can be entirely excused, especially if they happen to be bankrolled by a billion-dollar franchise.

There’s no need to limit ourselves to Majors or Cruise. It’s all too easy to come up with celebrities whose violent behavior has been downplayed, dismissed, and even defended because it was executed within the moral void that the Method supposedly creates. Dustin Hoffman, who was not just famously but infamously scolded by Laurence Olivier for depriving himself of sleep to prepare for a scene in John Schlesinger’s 1976 film, Marathon Man (“My dear boy, why don’t you just try acting?” the great Shakespearean is said to have said), brought this approach to the set of Kramer vs. Kramer three years later. According to a , Hoffman, “allegedly slapped…and taunted her with the name of her recently deceased boyfriend during…filming”1. Anything that gets you into character, right? How generous of Hoffman to support his colleague in doing the same!

I think of the Method as a dialectic2 of sorts: this series of techniques, exercises, and preparations for performance is undertaken in order to create the circumstances for artistic inspiration—meaning that while it cannot guarantee that inspiration, per the Method’s father, Konstantin Stanislavski, such inspiration almost certainly cannot happen without it. Contrast this with this “the ends justify the means” interpretation of the Method that I’ve outlined above, which reduces this somatic tradition of art-making to a rhetorical framework: This violence didn’t happen, and if it did, it doesn’t matter, because it was done in the name of Art. In this mindset, not only is art is degraded by the elevation of violence, but violence becomes a prerequisite of Art, a designation that can only hope to one day measure up the most valuable commodity of all: the intellectual property.

Which brings me Julianna Margulies, she of The Good Wife fame, whose recent racist and genocidal statements (and non-apology) regarding black lesbians, queer and trans people, and the Palestinian people—who, at the time of this writing, are undergoing a post-“humanitarian pause” intensification of assault by the Israeli army, which is using AI technology to create a “mass assassination factory” of cornered human beings—drew outrage from anyone of conscience.

Now, to be clear, as far as I know, Margulies is not a Method actor. I can find no evidence that she had any Method training, nor has she made any other statements aligning herself with any of its associated schools of thought. But her bizarre claim of lesbian identity in order to access an (implicitly white) lesbian moral authority over the black dykes, queers, and trans students of Columbia University who are agitating against Zionism for free Palestine—all because of a role she plays for Apple TV!—immediately made me think of the ways that the Method is wrenched from its long, complex, interdisciplinary, and often politically progressive history of the performing arts to reinforce patriarchy, white supremacy, and capitalism3. Like the worst offenders of this co-optation, Margulies has allied herself with a nonexistent person (a random lesbian) over living, breathing, bleeding Palestinian people; no, not even with a nonexistent person, but with an identity category that politicians and warmongers are only too eager to pervert to keep us dykes, fags, and trannies that are in solidarity with the oppressed in line with their murderous objectives.

The 2016 Pulse nightclub shooting was the first time I ever heard Republicans prayerfully invoking the rights and safety of people like me—people “like me” meaning white gays, convenient pawns to shore up pro-war, pro-imperialist, and anti-Arab and Islamophobic sentiment. That’s where my mind goes when I hear shit like this from people like Margulies, all them of practically drooling over the fantasy of us getting thrown off rooftops so they can make real their other fantasy: the elimination of the Palestinian people.

Margulies’s impoverished conception of personhood is laid bare by her hackneyed approach to her art. One betrays the other. “Not in our name!” is insufficient, but it is the first step toward a bold and active solidarity movement; it is the beginning to something of substance, which I have not yet, but hope to, attain.

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

1Remember when Hoffman went viral in 2013 for an interview where he cried about kinda realizing that women are people when making Tootsie (1982)? Then a few years later he got MeToo’d. Luckily, his friends who love women and are definitely not racist, like Liam Neeson, Bill Murray, and Chevy Chase, all came to his defense.

2No promises that I’m using this term correctly. Here’s a meme.

3Jade gets me: she sent me the link of Margulies’s statement with the very same idea.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 55 followers