Davey Davis's Blog, page 21

February 16, 2022

David Davis 37, part 5

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

Listen, I’m 33 years old, which means that when I watch my teen sister use YouTube, I feel like Jane fucking Goodall.

The apparatus appeared when I was in high school and she not even a twinkle in my stepdad’s eye. While we both now go on YouTube, I simply adopted it; she, Bane-like, was born in it, using it exponentially more frequently and utterly differently than I do. The influencers, recaps, gameplays, unboxing videos, and tutorials that she watches are, for her, like after-school television was for me when I was roughly her age, but while being distinct from “adult” culture (which makes sense, given that a discrete children’s culture is more easily commodified). I use these things on occasion when I need to. She’s been marinading in them her entire life.

Though we’ve had the requisite conversations about online safety, I try to stay aware of her YouTube activities (I worry a lot about her getting red-pilled or catfished), which is hard to do because what I’ve seen is, for my tastes, excruciatingly tedious. Minecraft experts with names like Dream. Something called Five Nights At Freddy’s, which for years I thought was an unlistenable music group, but which turns out to be a “survival horror video game.” Hypnotically-breasted anime characters. White guy comedians who are not even comically unfunny but who, I have to admit, I would probably have found cool and hilarious were I her age. I never feel the distance of the almost-twenty years between us as much as I do than when she briefly welcomes me into her online media habits.

Because if you sat me down in front of YouTube and ask me to share something with you—something fun and funny and entertaining—this is probably where I’d go first.

While preparing to wrap up this series about the art of the interview, it occurred to me that some of my favorite interviews are ones in which the subjects upend what can feel like a disciplinary or even humiliating ritual, particularly if those subjects aren’t straight white men. Not that straight white men aren’t capable of this as well—I don’t care one way or another about actor Jonah Hill, but his refusal to allow interviewers to talk about his body as if it were disgusting is cool—but they’re not what tends to capture my attention.

Divas on divas, made by ex-Gawkerite Rich Juzwiak all the way back in 2011, is not just the upending, or even co-opting, of the interview by divas in conversation with other divas—it’s also pure gay adrenaline. Interlinking clips of pop stars and singers like Lady Gaga and Mary J. Blige talking about other pop stars, Juzwiak makes you feel like a speedball at the mercy of an alpha warming up for the big match. From Janet Jackson activating my fight-or-flight response by demurely implying that Madonna is classless, to Mariah Carey simply saying, No., at the mention of Christina Aguilera, this ten-minute clip is a daisy-chain of feminine terror, not a one of them failing to rouse the panicky bliss of seeing a straight woman and knowing, in your bones, that gay people are obsessed with her.

Between the slams, real generosity offsets, and even enriches, the cuntiness: Whitney Houston describes Mariah Carey to Wendy Williams as “a little lamb chop.” Celine Dion calls Mariah “fabulous, with a lot of class.” Britney Spears, infamous for her sweetness, doesn’t have an unkind word to say about anybody, even Madonna, who everyone else obviously hates. My favorite clip is one where Whitney, leaning back in an almost-caricature of seriousness, her upper lip just a little too firm, allows that Madonna, “works hard at what she does.” Fatality!

True to form, Juzwiak has collated camp for us, poking fun at these women’s expense while simultaneously taking an authentic pleasure in their sense of humor and ferocious nerve. While not the sole domain of women, is the campy interview—an upending by interviewer, subject, and audience, sometimes all at once—not predominated by them? Before Zach Galifianakis did Between Two Ferns, there was the iconic (and unironic) Nebraskan broadcaster Leta Powell Drake, who died this past September; Tom Cruise may have made that couch a legend, but that furniture first belonged to Oprah, who gave him the stage and both hands to hold.

To rephrase a question I asked in Part 1 of this series, how does a good interview hold its audience’s interest over time? Juzwiak made this superclip over a decade ago, and it comprises celebrity culture going back before I was born, and yet it still maintains its hold on me, thanks in no small part to the power of the internet.

But this doesn’t mean that its appeal remains static. It changes as I change, its pleasures shifting with time (I only love Whitney more. I only love Madonna less). When I remember with Divas on Divas, I’m remembering with myself, too.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

February 14, 2022

GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY: a new giveaway

I’ve known of interdisciplinary artist Zach Ozma for many years now. Friendly satellites back in Oakland, where I encountered him through our mutual friend, writer Emme Lund, Zach and I didn’t really get to talking until he was touring in New York to promote the Lambda-winning WE BOTH LAUGHED IN PLEASURE: The Selected Diaries of Lou Sullivan, which he co-edited with Ellis Martin, in 2019. I liked him very much right away; handsome and accomplished though he is, Zach’s cozy effervescence makes it impossible to feel intimidated or uncertain around him.

I hope you keep this in mind when I tell you that this working artist of some renown is going to be GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY’s second special guest star1. How exciting slash don’t be shy!

That means that you can now submit your queer art questions for the chance to have Bad Gay and Zach answer them. Everyone who submits under this theme gets:

(1) 3-month subscription to GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, which includes access to our archives

(1) Chance to have their question answered by the good doctor and our esteemed guest

(1) Entry into a raffle for stickers, pins, and posters made by Zach, plus the big enchilada: this Zach Ozma creation

But wait a minute. Queer art questions—what does that even mean? The prompt is open-ended, but here are some thought-starters:

queerness, art, queer art, artistic practice, artistic jealousy, feelings around success/failure, how to get or stay inspired, how to prioritize art in your life, what the hell is queer art anyway??, the weirdness of being curated as ~queer~, am I really making art?, should I quit my jobs and move to the mountains to make art? what does queer art do?

So, to recap: Send your queer art question to badgayadvice@gmail.com by midnight on Sunday, February 20. Have a mutual aid or reparations project to recommend? We prioritize individuals, groups, and orgs led by and for black, POC, indigenous, trans, queer, incarcerated, disabled, drug using, and sex working individuals, so please send them our way! You’ve shared $2,827 in subscriber funds, so it’s gonna be a big one 😎.

GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY is an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of projects like No New Jails NYC, , SWOP Minneapolis, For The Gworls, St. James Infirmary, No North Brooklyn Pipeline, and SWOP Behind Bars, plus many more.

1Revisit our first, when friend-of-the-column, Frankie, advised a reader on sex, gender, and kink.

February 8, 2022

David Davis

When I was younger, I did not understand how poet Minnie Bruce Pratt could refer to Leslie Feinberg, who used a variety of pronouns in hir public life as a transgender lesbian and revolutionary communist, as she and her in their home together. They had this intimacy, as Pratt describes in a recent interview, “as lesbian lovers.”

February 7, 2022

David Davis 37, part 4

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

John Berger said that glamour cannot exist “without personal social envy being a common and widespread emotion.” I will pretend, for just a little bit, that we’re helpless against this truism. That it is romantic, rather than implicating.

In profiling legendary talk show host Dick Cavett in earlier installments of this series, I’ve examined the art of the interview mostly in terms of the Interlocutor’s creative choices. But since I think of this art form as a collaborative one, I should also consider the interviewee in this rough survey of what it means to be publicly questioned, sometimes before a live audience and often with the purpose, spoken or otherwise, of generating money-making attention through scandal or humiliation. After spending so much time with Cavett’s interview with actor Richard Burton (which I jokingly refer to as my favorite movie), it seemed only natural that Burton’s ex-ex-wife, actor Elizabeth Taylor—in her time considered one of the most beautiful and controversial women in the world—would appear to me as a fitting subject.

There are countless interviews with Taylor from which to choose, but the first that came to mind was one she held with Barbara Walters in 2006 to promote her book, Elizabeth Taylor: My Love Affair With Jewelry.

The Taylor of my teen years ought to be distinctly unglamorous: an elderly, embittered woman whose tabloid-trashings for her age, weight, marriages, substance use, relationships with other celebrity weirdos, like Michael Jackson, and disjointed political commitments1 are just about as old as my pre-war grandmother. Shilling a book that is a capitalization on her history of glamour, she comes across as wispy, unfocused, goofy. “Shame on you!” she says, searching for a camera to glare at when Walters mentions that the kids of today aren’t familiar with Burton. He was, she says with a snarl, “a hunk!”

Even when I saw this interview for the first time, I sensed the depth of that glamour, legible even for someone who had only seen her onscreen in the live-action version of The Flintstones (1994). Over the years, I return to it for a good laugh, because it really is quite funny. It’s a puff interview for coffee-table book with a woman who is no longer taken seriously, if she ever has been (although Burton, and many others, have praised her talent—as distinct from her beauty or cultural impact—over the years). But still, the glamour is there, straddling grand lady and gay icon to generate the tension required for camp, where worship and denigration, over-identification and ownership, meet in the meat of affective satisfaction.

“This red is from god,” she declaims, gesturing to a chain of rubies among her collection. “And those green little things…” She doesn’t even say “emeralds!” She’s so goddamn rich—the collection was valued at over one-hundred-million at the time—she doesn’t even have to call the rock by its name!

There is something alluring about a woman who will not apologize for being so fabulously wealthy, so fabulously fabulous. She feels like royalty, like she was sent down to earth by god. Her beauty and acclaim is so tightly enmeshed with her scandal and humiliation as to be a part of it, like gemstones in a Cartier necklace, and yet somehow, even with my disbelief unsuspended again, she endears herself to me, this bizarre old woman.

“Personal social envy…” as Berger said. The remarkable thing about having one’s consciousness raised is that what you think doesn’t always change how you feel.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

Subscribe & Support Mutual Aid

1Pro-gay and pro-Zionist—the latter to a weird and disturbing degree—until her death, she anticipated the neoliberal moment, as it were. Icon!

January 28, 2022

David Davis

Years ago, I came across an evopsych-y theory for OCD that got stuck in my brain.

Certain obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviors, the argument went, were of use in early human societies, meaning that those who expressed them had more opportunity to reproduce and thereby pass on that genetic tendency. The clusters of characteristics that now fall under the umbrellas for hoarding1, contamination, or scrupulosity OCD2, for example—which are here and now pathologized as mental illness—actually provided a reproductive edge. Maybe today’s collectors were yesterday’s top-dog protein gatherers. Maybe obsessive cleanliness, even when existing in the absence of germ theory, staved off disease. Maybe the kind of person inclined to ritual and mystical meaning-making could be a little intense 10,000 years ago—but maybe that same person used their inclinations to help build culture that enriched social life and strengthened the collective.

More recently, I read a book about OCD that posited the above theory’s opposite. Certain newer studies suggested that OCD’s calling-card behaviors—like counting, collecting, and checking—actually predate meaning. That is, you did not learn about the danger of germs and only then, when encountering an environmental trigger that culminated in a DSM-V-able OCD, become germaphobic. Rather, your body decided that it needed to wash its hands until they bled; needed to count the stairs up to your apartment every day 13 times, at minimum, very very very important; was simply just gonna lock and unlock the front door so many times that you were late for work that day. Then your unconscious mind filled in the empty bits to give all of that activity some purpose.

Context creates the narrative, giving discrete events the reassuring structure of plot, but the compulsion never relied on a story to exist. What’s worse than needing to pray for everyone you know before you fall asleep or they will all die a fiery death? Knowing that you must go through with it despite the fact that you also know this isn’t true.

Now, listen. I don’t know much about OCD, and next to nothing of medical history, psychology, all that stuff. I have no idea which, if either, of these theories is true, or is generally accepted by the medical establishment, or even if I have accurately regurgitated them here for you.

But I can tell you which theory is more appealing to me, as a person with an interest in obsessive and compulsive behaviors, whether or not they qualify as mental illness. I like the latter notion: the idea that sometimes our bodies do things without our brains, and that for some reason—the need for internal coherence or fantasy or self-protection of some kind—our brain then decides to cover our body’s tracks. It feels godlike to make meaning from nothing, even if that meaning isn’t strictly factual (which isn’t to say that it isn’t real). Considering the frequency with which his abominations are found walking the earth, it sounds like god is often wrong, anyway, so maybe this inductive approach to suffering makes us more like him than we realize.

a.image2.image-link.image2-730-584 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 125%; padding-bottom: min(125%, 730px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-730-584 img { max-width: 584px; max-height: 730px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-730-584 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 125%; padding-bottom: min(125%, 730px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-730-584 img { max-width: 584px; max-height: 730px; } Needles are my sweet spot. I’ve had my fair share of bad medical experiences, but few involved needles, per se, though I did develop a brief aversion to blood draws after I was in a year-long paid study where I went in twice a week for labs. I could only count on a real phlebotomist being at the clinic 75% of the time; otherwise, I got stuck with a specialist (an OB/GYN, usually, as the study had to do with so-called “women’s health”), and MDs suck major ass when it comes to finding and tapping veins, even with me, whose veins are often complimented in that kind of scenario. I’m vain about my veins.

Anyway. When Dahlia got me into needleplay almost ten years ago, I came to it without any needle baggage. I didn’t have any latent psychic needs to address or any phobias to overcome. I did it because it’s a fairly easy, low-risk, relatively inexpensive way to be hurt and produce blood that doesn’t really scar, or even leave many marks, if you don’t want it to. And also because Dahlia likes it.

A decade later, I’ve had thousands of needles inserted into my skin by her and other people, and as with any other practice, I’ve gotten better at it. The first or second time, Dahlia only put in a handful—maybe eight, maybe just four—and they were probably 26g, or something like that (which is quite small. Standard size for blood draws is 21g, I believe). I was so high off the adrenaline that I went to another room to be alone so I could laugh. Now I can take dozens of needles at a time, sometimes quite big ones, before it starts to feel like an effort. Sometimes my top fucks me with them—which is to say, they twist and pull, yank them out then reinsert at a different angle, finding ways to make the tiny pain of broken skin feel more like a knife than a pinprick. Sometimes they do other things, like wrap me in plastic with the needles still inside and hit me with leather, as Jade and Ez did the other night.

I still get that adrenaline rush, just like the first time, but it’s rarely as strong, and it takes much more than a casual scene to induce that drug-like euphoria. Because if you want intense highs, you must first experience intense lows. That’s the deal—I don’t make the rules. You have to feel pain and fear if you want to also feel the good stuff, and I make it a point, these days, to have easy scenes as well as stressful ones. Depending on the scene, in fact, a few needles can even be a nice way to unwind before bed.

There is still an element of punishment to needleplay, because of course it hurts; but that pain is the only way in which it resembles the other kinds of discomfort that interest me. My needle scenes are the least hierarchical, with very little in the way of power exchange. There is no roleplay, no humiliation other than a little teasing, no direct lines to negative early experiences, like spanking, or raced, gendered, and classed sociocultural associations, as is necessarily the case with corporal punishment. My relationship with needles was created consensually, in adulthood among other adults in fun, sexy contexts. Now that I think about it, it links most closely with the tattoo as it’s constructed today where I am: adult, consensual, more or less amoral and apolitical, vaguely sexy, a little challenging, like running a 10k.

What I’m saying is that needles are, in a way, a blank slate for me. They do not put me in conversation with my distant past, like other aspects of SM, and the older I get, the more I appreciate and value this aspect of the experience. My body needs to regularly indulge in discomfort to be comfortable, for some reason. But what sets needles apart, as a way to fulfill that need, is that there is a minimum of psychic distress that must be undergone in the process. I want the sensation and I join others to take it. As I make and remake meaning from it, I am not fighting against an ancient narrative, fossilized by culture and neural memory. In writing my own story, I am struck, again and again, by how fragile the categories of both pain and pleasure really are.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

Subscribe & Support Mutual Aid

1Noting that “hoarding” is the more common—and far more stigmatized—term for collecting OCD behaviors. I’ve used it here because it’s one that people recognize, but please using “collecting” when you can instead.

2That is, if an illness of the past can be said to be an illness of the present, even provided it could be produced because of similar conditions, which it couldn’t.

January 22, 2022

David Davis 37, Part 3

a.image2.image-link.image2-651-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 89.42307692307693%; padding-bottom: min(89.42307692307693%, 651px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-651-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 651px; }

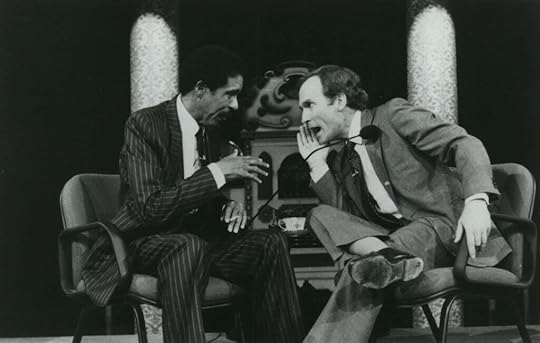

a.image2.image-link.image2-651-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 89.42307692307693%; padding-bottom: min(89.42307692307693%, 651px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-651-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 651px; } There are two sides to the Dick Cavett coin, but we’re capable of nuance here at DAVID, aren’t we? It suits our subject, too. “You invert things so beautifully,” actor Richard Burton, the star of Part 2 of this series, tells Cavett in 1980. Five years later, while interviewing director Paul Schrader about his bio-drama, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters, he makes the mistake of saying that writer Yukio Mishima killed himself at the age of 54. “45,” Schrader corrects him. “I always reverse numbers when it’s the other side of the world,” Cavett charms back.

As much as I’ve appreciated The Dick Cavett Show’s YouTube renaissance, it’s generated a lot of Cavett lionizing without enough Cavett critique. In an early-pandemic piece for the BBC, Christina Newland claimed that Cavett was the “greatest talk show host of all.”

Cavett’s style of hosting and of initiating genuine conversation with his guests – neither pandering to them nor acting smugly superior – reflected how entertainment and cultural spheres were liberated by the bohemian spirit of the 70s.

Now, I like this piece. It’s an informative bit of writing that captures the nostalgia that streaming Cavett can evoke for people born after his heyday, especially when compared with the dismal quality of late-night television in the 21st century. As Cavett himself said a few years back, “There’s no honor, now, to have a talk show.”

But while I agree with Newland that Cavett is one of the greats, if not the greatest, she’s dead wrong about his treatment of his guests. Though genuine, funny, and at times even sweet, Cavett can be not just smug and superior, but cruel. In fact, there are guests with whom he is nakedly dehumanizing, particularly when those guests are white women, and especially when those guests are black men; unsurprisingly, precious few black women were ever on The Dick Cavett Show as guests during its prime, and off the top of my head, I can only think of two—Shirley Chisholm and Alice Walker—out of the dozens of episodes that I’ve seen. To overlook this tendency toward bigotry (to dust off a word that Cavett himself would have used back in the 70s) is not just to do a disservice to those guests, but to misunderstand Cavett as an interviewer.

Though Cavett’s challenge as the Interlocutor—at which he often succeeds, and which others so often fail—is to draw history, insight, truth from his guests, his own shortcomings, as we may euphemistically refer to his supremacy logics, regularly overwhelm him. What makes these failures so striking, at least to me, as a white person of redacted gender, is that I get the sense that he does it defensively; in moments of powerlessness, insecurity, or mere dead air, Cavett will jockey for the top by belittling his guests, and when this happens, the guest in question is rarely a white guy.

This tactic for self-aggrandizement is far from unheard of among men and white people, whether or not they/we are hosting a talk show. But when I use the word failure, I mean it in the sense of Cavett’s project as interviewer, rather than in the sense of him being a nice person. In these moments, Cavett changes the focus of the interview; that is, he fails at his task of revealing his subject, and instead reveals himself.

a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 150%; padding-bottom: min(150%, 1092px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 1092px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 150%; padding-bottom: min(150%, 1092px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-1092-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 1092px; } These failures are all the more striking when you consider Cavett’s reputation for control. Taut as piano wire, Cavett’s penchant for preparation is so severe that it actually works against him; he would go on to joke that in the early days of his show, he trained himself to have stock questions at the ready for when he missed what a guest said because he was “too wedded to his notes.”

This reputation for control is why Cavett’s loss of it when with a guest who isn’t a white man is so fascinating, to me, anyway. This isn’t to say he doesn’t sometimes go in on white male guests1, but he tends to be forgiving of even the trickiest weirdos, from the Thin White Duke to Brando at his most lampooned. At worst, the energy Cavett brings to these guests isn’t unlike that of a kid brother: irritating but harmless. As Esquire writes, while he doesn’t throw softballs, he’s “no firebrand griller,” either.

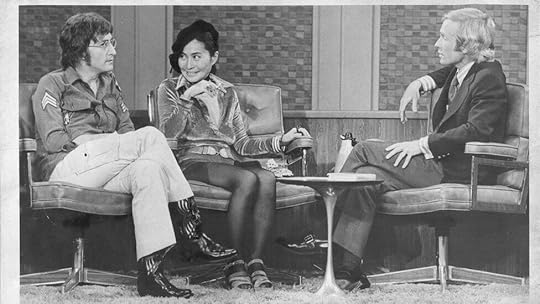

A possible emotional inverse of impish, an adjective often used to describe Cavett, is, I think, waspy, which is how he can be with the women he interviews, especially if they are regarded as sex symbols. “Here they are, Jayne Mansfield!” is the joke that famously got Cavett his breakthrough writing gig on Jack Paar’s Tonight Show, and I’ve often thought that its offense is located in the assumption that Cavett has the altitude needed to condescend so hard. For every interview where he mansplains to Gina Lollobrigida or speaks over Yoko Ono’s head is another where his attempts at belittlement fall flat because, well, he’s a little bitch. Most of the women he interviews, white or not, have been socialized to disappear male aggression with grace and camouflaged wit, but a lot of them let it rip with Cavett, who’s so easy to humiliate it’s almost not fun. Whether he’s being ganged up on by Janis Joplin and Gloria Swanson (a setup that feels like an acid trip in and of itself), or Lucille Ball and Carol Burnett, one has to wonder if Cavett actually likes it. He certainly asks for it.

a.image2.image-link.image2-751-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 103.15934065934067%; padding-bottom: min(103.15934065934067%, 751px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-751-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 751px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-751-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 103.15934065934067%; padding-bottom: min(103.15934065934067%, 751px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-751-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 751px; } It is easy to recognize the sexism in Cavett’s treatment of (mostly) white women because, broadly speaking, we still only recognize sexism as a white woman’s problem2. I would suggest that Cavett’s treatment of the black men who are guests on his show is also sexualized, perhaps even to a higher degree than that of his white women guests.

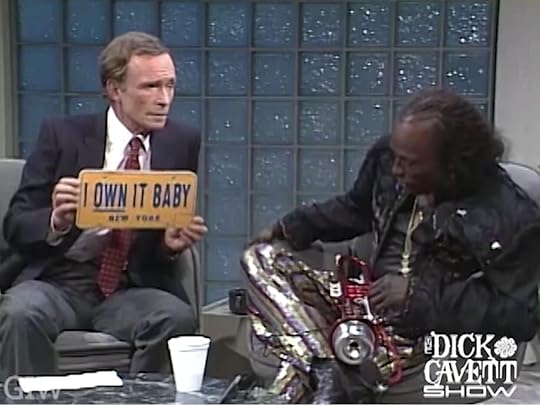

Take his 1985 interview with Eddie Murphy. It begins with Murphy teasing the house musicians, a group of white guys who’ve never been to New Orleans, for calling themselves the New Orleans Jazz Band. I’ve said that Cavett is charming, but Murphy, as we all know, could out-charm him any day of the week. Still in the midst of his atmospheric rise to fame, Murphy’s charisma is soft yet sparkling. As Cavett triangulates the young comic’s burgeoning career with that of the even-then legendary Richard Pryor, he quickly draws Murphy into a conversation about his earliest memories. When he brings up Mark Twain out of nowhere, you barely have enough time to recognize that you’re on edge before he asks Murphy, his voice rippling in gleeful caricature, “Are you offended by the word ‘n- - - - -?’”

Murphy’s demeanor transforms. “Why…Where is this coming from?” he asks. He is bewildered. He hardens.

“Did I say that?” cries Cavett, campily clutching invisible pearls.

The interview continues. Though he recommences his teasing, Murphy is never once rude, but neither, I think, is he ever warm again. I was shocked to hear the word come from Cavett’s mouth, though perhaps I should not have been. While surely informed by my inexperience with racism, however, my shock was also due to having watched, just before, one of Cavett’s sycophantic interviews with Pryor, the comic genius that he plainly idolizes—and whose work inspired Murphy, too.

The sexualization takes more shape when you zoom out from this one interview. While talking with Marc Maron decades later, Murphy says that he got to know Cavett well outside of The Dick Cavett Show. Cavett “popped up” a lot, Murphy reports. “I used to hang out with Dick Cavett a lot. If you dared him to do anything he would do it.” Once, while watching Diana Ross perform at Madison Square Garden together, he dared Cavett to grab Ross’s ass. “Why you doing this to me?” Cavett plaintively demanded. But then he fucking did it—went right up onstage and did it, to Murphy’s bemused entertainment. While I won’t excuse Murphy’s role in this scenario, Cavett’s willingness to entertain it screams humiliation bottom. How can such a grudging fixation on someone, described in some circles as a fetish, not be sexual, I wonder? To speak of triangulation again (and to evoke, on some level, Barbara Kruger): how can you, as a man, sexually assault a woman at another man’s invitation and not feel an erotic charge with him?

From all that I’ve seen and read, Cavett appears to simultaneously worship and revile black men, compulsively seeking their attention by provoking outrage and offering bizarre displays of submission, usually in encounters that make him appear more like a member of the entourage than a friend. There’s another story, this one told by Cavett himself, about going on vacation with none other than Muhammad Ali. When Cavett cooked breakfast for the both of them, he turned around to find that Ali had eaten all of it.

When he realized what he’d done he put on a hilarious, pitiful sad look and murmured, “Oh, Dick. You never gonna invite me back.”

It was so sweet, I almost cried.

Like all bigots, passive and active, Cavett has this tendency to position himself as a pseudo-victim, even in this attempt at humor, which lands for me as both condescending and pathetic. It’s akin to the extremely cringe largesse that Norman Mailer demonstrates when the writer and Ali are on The Dick Cavett Show together in 1970. “I came here to pay my respects to you tonight, that’s why I came on after you,” Mailer tells Ali, offering his honor like an adult giving a child a ballon, grinning with all of Spongebob’s teeth and none of his humanity3. Mailer waits, as if expecting Ali—who almost went to prison and missed out on four of his prime athletic years for refusing to be drafted into America’s imperialist war against the people of Vietnam—to be grateful for his praise. Ali’s response is steeped in a quiet dignity that imperils the remainder of the interview with its restraint. It punctures Mailer’s balloons. It makes shit awkward.

a.image2.image-link.image2-663-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 91.07142857142857%; padding-bottom: min(91.07142857142857%, 663px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-663-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 663px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-663-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 91.07142857142857%; padding-bottom: min(91.07142857142857%, 663px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-663-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 663px; } Over the past few years, I’ve begun to think of the interview as an art form, one serious enough to merit rigorous critique. Cavett, like almost everyone, is a person of his time, and we are hardly surprised that he demonstrates racism, sexism, and the like over the span of his 50-year career. These are, in my opinion, personal ethical failings with personal and social ramifications for the people they effect.

They are also artistic failings: to succeed creatively as an interviewer, one must interview a subject, and the subject can’t be a subject when they’ve been objectified. But even in his obscuring of his subjects, Cavett, as I’ve said, reveals himself. To paraphrase painter Francis Bacon, when you paint something, you’re painting yourself, too.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

Subscribe & Support Mutual Aid

1There are exceptions, as with the famously homosexual and at that point socially dethroned writer Truman Capote. “I haven’t seen very many people for the last three years,” Capote tells Cavett in 1980. “A lot of people would say it’s because you have no friends left,” Cavett lobs back.

2Exacerbated by straightness, cisness, money, thinness, non-disableness, etc.

3Like any normal person, I loathe Norman Mailer, who physically sickens me.

January 17, 2022

David Davis

a.image2.image-link.image2-663-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 91.07142857142857%; padding-bottom: min(91.07142857142857%, 663px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-663-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 663px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-663-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 91.07142857142857%; padding-bottom: min(91.07142857142857%, 663px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-663-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 663px; } I haven’t written about sex in a while. As I wrote a few months ago, I have been trying to think about it less: I’m sick of intellectualizing every emotional fluctuation and fantasy, every craving and mood.

There are risks to this compulsive cataloging, itself a reaction, in part, to the modern world’s technologically-produced proliferation of pleasures, with which identity and a variety of disciplining forces (e.g., criminalization, medicalization) have become intertwined. The “oracular” algorithms that clog our feeds with ads for so-called genderless clothing and TikToks that mirror back at us our own cherry-picked characteristics, like our ethnicity or our interest in vegan baking, supposedly know us better than ourselves. Initiating a feedback loop of identity, desire, and ultimately consumption, this artificial knowledge informs and influences—produces, as the theorists say—what those selves are, and could be.

These risks don’t come without rewards. The at-times paradoxical blend of radicalization and co-optation, like consciousness-raising vs “awareness,” or therapy1 vs. self-help infographics, with which we locate our selves in this hegemon, sometimes favors us. In 2020, when I was writing a DAVID series on genital preference, I tweeted: “the cool thing about having sex with a lot of people is getting to see a wide variety of bodies in sexual and non-sexual situations. it has informed my understanding of so many things, especially so-called ‘genital preference.’” The interrogation of our own desires, as I went on to tweet, has implications for our identity and self-conception; this can be (politically) formative as well as regressive.

These interrogations are why I could be radicalized by my marginalization, such as it is, and why, more importantly, I could build outward from my individual identity to a politic that’s not actually about me. It’s funny to think that picking up a Reader’s Digest in an auto shop when I was 17, in which I read that masturbation is actually okay and won’t kill you or make you go blind, was one of the many small revelations that made it possible for me to eventually become a person, which was foundational to my eventually becoming a political person.

These revelations are temporally as well as quantitatively incremental. Learning how to decouple sex from procreation, heterosexuality, and monogamy, and to subvert the scripts we’re trained from birth to follow—that is, to denaturalize sex—requires time and exposure to people, experiences, and information. Not all of these exposures make sense to us immediately, like the Reader’s Digest article did for me; revelation can be cumulative, contextual, a practice in hindsight, and not just a lightning bolt.

For example. A year after reading that Reader’s Digest, while drunkenly fooling around in a car with some straight guy, I became too distracted by what he looked like to fuck; instead of getting angry or pressuring me, he listened while I talked at length about much I wished I had his body (?!?!), then drove me to a Jack In The Box and bought me food to soak up the booze. I’ve always looked back on that experience with gratitude—he was kind to tolerate my strange behavior, and he didn’t even try to rape me. Only relatively recently did I understand what was actually going on between us, or between me and his body, anyway.

Moments like that one that help drive that denaturalization of sex, but rarely are they totalities unto themselves. It’s context, like I said. But there’s something else to it: the sexual self-knowledge that leads to political awareness and action must be chosen, again and again. It cannot be passive, because sexual repression, cissexism, comphet, and capitalism are not working passively against us. Which isn’t to say that they exert their pressures uniformly. The pressure comes from all sides, not just above.

For example. We are aware that heteronormativity motivates with punishment. It also motivates with incentive, which is something that straight people have a harder time acknowledging, especially these days. The gender and sexual scripts that we all know, though maybe don’t always recognize, often offer both punishment and incentive: girls wear pink, boys don’t cry, marriage is romantic, the nuclear family is safe, natural, and eternal. There are scripts for sexual intercourse, too, and while they can be stifling, constraining, or boring (or worse), these scripts are also incentives in themselves. That’s because, when you believe that there’s only a handful of ways to fuck, sex becomes remarkably easy. This is one of heteronormativity’s incentives to conform.

I don’t mean that straight people can’t or don’t do weirdo sex shit, or that being able to do a handstand while getting drilled means you have some kind of advanced understanding of sexuality and yourself, or that sex that looks normative can’t be pleasureful. What I mean is that we’re initiated into sex as something that can be learned, mastered, and replicated, over and over, like it’s a product on an assembly line. It is always the same, across time, space, and bodies. We’re all familiar with the script of cis man and cis woman having vaginal intercourse2, so much so that most of us can do it in our sleep, even if we don’t appear in the script whatsoever.

So what’s the benefit of this sex script, then, if it’s so deleterious to pleasure and connection? How is this an incentive of heteronormativity, and not a punishment? Well, if you know exactly how sex is supposed to be—what you’re supposed to do, how you’re supposed to do it, and how it’s supposed to make you feel—then you don’t have to be present for it, do you? You can do it, or have it done to you, in your sleep. It’s not just that deviation from “normal” sex is pathologized, criminalized, or unimaginable—it’s that following the script for normal sex can be done with a minimum of static, if not effort or pain. Heteronormativity renders sex as a specific series of acts that is done with specific people, with specific goals in mind, so much so that concepts like consent are challenging to understand and difficult to introduce into our sexual practices. Sexual practices like consent that we, as good feminists or leftists or whatever, can all agree are good are also difficult, because they require effort, negotiation, vulnerability, accountability, and presence.

a.image2.image-link.image2-480-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 65.93406593406593%; padding-bottom: min(65.93406593406593%, 480px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-480-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 480px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-480-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 65.93406593406593%; padding-bottom: min(65.93406593406593%, 480px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-480-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 480px; } Like I said, there are risks to overthinking it. But being present can often feel uncomfortable, and no more so than when you’re trying to unfuck your approach to fucking. These sexual scripts seem simple enough on the surface, but they have roots. They’re like mushrooms that way, with fruit that we see, and miles of mycelium hidden deep underground, so that it’s easy to mistake an ecosystem for a single organism.

My advice is to follow pleasure, but there is a caveat: pleasure, like sex, like gender, like desire, also needs to be denaturalized. This is where more challenging avenues to pleasure, like difference, pain, and even abstention, come into play. I recommend those, too.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

Subscribe & Support Mutual Aid

1This is not to say that we aren’t critical of therapy or its role in the medical-industrial complex.

2A euphemism that I actually avoid because of its inherent implication of penetration of a certain kind. Put another way, why does “vaginal intercourse” mean cishetero penis-in-vagina? Why wouldn’t it mean any other configuration, including one in which penetration isn’t happening, isn’t happening in the vagina, etc.

January 8, 2022

David Davis 37, Part 2

a.image2.image-link.image2-540-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 74.17582417582418%; padding-bottom: min(74.17582417582418%, 540px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-540-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 540px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-540-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 74.17582417582418%; padding-bottom: min(74.17582417582418%, 540px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-540-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 540px; } Forgive me if you’ve read this spiel before, but 2020 was hard. I spent half of COVID-19’s inaugural year at my mom’s house in Northern California, helping her care for my older sister. On top of multi-day shifts with C (whose needs can often be intense), I was working full-time and freelancing, too, petrified of getting laid off again, as I had in the first months of the pandemic. My gay family was hundreds and thousands of miles away, and I was by myself in a town where I don’t know a soul, other than estranged relatives and two of my three sisters, who due to age and other factors are more like my children than my peers. There have been times in my life where I have felt more isolated and exhausted, but there haven’t been many, and 2020 was the first that the possibility of my sweet C, alone in a hospital that might consider her IQ reason enough to let her drown on dry land, ornamented my nightmares.

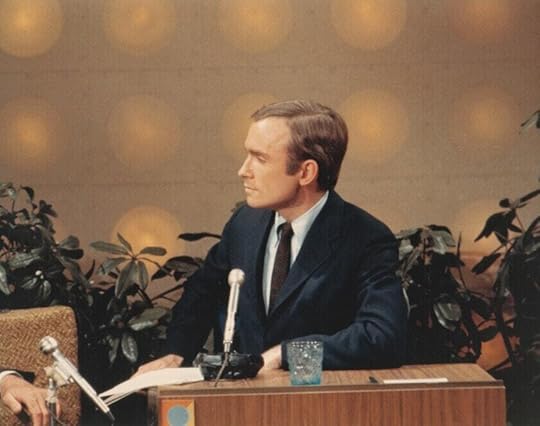

I don’t remember why I started watching episodes of The Dick Cavett Show on YouTube, but suddenly it was a part of my solitary nighttime ritual, the hour or two before sleep when I laid down on my mom’s yoga mat, chain-smoked joints, and anticipated another 16-hour-day of muting C’s screams over Zoom meetings while trapped indoors by viral plague and fire season. Delighted by the seemingly endless roster of famous subjects—including Salvador Dalí, Katharine Hepburn, Judy Garland, Miles Davis, Muhammad Ali, Marlon Brando, Orson Welles, Lucille Ball, Truman Capote, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Richard Pryor, and my beloved Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni—I found myself entranced by the pedantic patter of this boyish Midwesterner, who over the course of almost 40 years of hosting his self-titled talk show has aged from Pinnochio-esque whippersnapper to batty examiner emeritus.

I started joking (mostly to myself, because I was mostly alone) that my new favorite movie was Cavett’s 1980 interview with Welsh actor Richard Burton, the Shakespearean heartthrob considered the successor of Laurence Olivier, and of a generation with Richard Harris, Peter O’Toole, and Oliver Reed (though in the interview he talks at length about his close friendship with American actor Humphrey Bogart, born a quarter-century before him). I was already familiar with Burton, but not overly, my association being mostly his leading role in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf (1966) and his supporting role as wife-guy to Elizabeth Taylor1, to whom he was married (and divorced) two times.

But despite Cavett’s reverential preamble to the episode, the actor, whom he describes as “graceful without effeminacy,” needs no introduction. Leonine yet poised, unleashing his languorous baritone with the razored elocution we recognize from his stage work, Burton’s fading physical beauty describes an unassuming yet arresting comfort in the spotlight. If you haven’t seen this interview, go watch it—right now. I could watch it over and over, and have, letting it play in my apartment as I do dishes or clean, sometimes catching myself raptly listening, while leaning on a broom like Cinderella, to what Vanity Fair called Burton’s “Welsh-barroom raconteurship.” You can’t believe that it’s extemporaneous, the way he spins outlandish yet tender stories about his coal miner father, expounds on the craft of acting, muses on attachment trauma and alcoholism, and coyly divulges old Hollywood lore; and yet were you told it was a performance, you would also find it unbelievable.

Shoeless, in a blue suit and brown tie, Burton appears older than 54, and indeed, he is only four years from his death of complications from alcoholism. Aged both by drink and his resemblance to a Roman statesman2, he speaks beautifully of his home—“I don’t know if it’s the coal dust in the air or the eternal rain, but certainly most Welsh people sing mellifluously,”—casually recites from Hamlet in both English and German, and charmingly disparages his looks, his acting, and his writing, calling his diary “unreadable,” though at the time you could find excerpts of it in magazines like Ladies’ Home Journal3. He doesn’t watch television and doesn’t like being touched by other actors, particularly when shooting love scenes. He tells Cavett that he calls everyone he respects by their full first name, and then, after an avuncular feint to the contrary, proceeds to call Cavett by his, igniting, briefly, a kind of male homosocial warmth that’s hard to describe without irony. Dudes rock.

But that’s all I’ll say about that. If I don’t leave Burton alone now, I never will. This post is not about him, but the man sitting to his right, in earth tones to suit the drab tail-end of 70s talk show decor. Petite and fine-featured, he’s a sparrow to Burton’s eagle4. In 1980, Cavett is 12 years deep into his solo show, in control, even if obviously impressed by his guest. Almost ingratiating, but not quite, he guides Burton through his earliest childhood and into the most sensitive of subjects of his life—booze, women, and the insecurities strong enough to plague a man who got halfway to an EGOT—navigating commercial breaks as gracefully as Burton the stage. “You are clever,” Burton tells him, and as abashed as Cavett plainly is, the little bird is unflappable. “You’ll notice that more and more as we go,” he says, and his audience laughs.

a.image2.image-link.image2-737-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 101.23626373626374%; padding-bottom: min(101.23626373626374%, 737px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-737-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 737px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-737-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 101.23626373626374%; padding-bottom: min(101.23626373626374%, 737px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-737-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 737px; } Then in his mid-forties, Cavett had had the kind of early success that, even skewed for his being a white guy and all, seems ridiculous in the age of the internet. After reading that Jack Paar, then the host of The Tonight Show, needed material for his opening monologue, Cavett wrote some jokes, put them in an envelope, and went to the RCA Building, where he hand-delivered them to Paar himself. Parlaying his luck (doesn’t that story feel massaged, like Lana Turner’s soda fountain?) into a writing gig on The Tonight Show and a brief career in stand-up, in 1968 he began hosting for ABC, and continued doing so, on one network or another, until 2007.

The Dick Cavett Show’s glory days, writes Esquire, “were undoubtedly in the early Seventies…The immensely more popular Tonight Show with Johnny Carson traded in big laughs, and his legacy can be felt in the fact that every current late-night host is either a former comedian or writer. But Dick Cavett, despite his stand-up background, was a conversationalist first and foremost. His was a subtle, impish wit. He was simultaneously disarming and confrontational. It made for some of the greatest televised interviews ever broadcast.” But Cavett is not remembered like his contemporary, Carson, or Carson’s successors, from David Letterman all the way through to James Corden (although when Stephen Colbert had Cavett on last year, he told him that he was his idol). For a guy who had enough of a presence to be threatened by President Nixon himself, he seems, if not forgotten, then often overlooked, at least here in his own country.

a.image2.image-link.image2-549-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 75.41208791208791%; padding-bottom: min(75.41208791208791%, 549px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-549-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 549px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-549-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 75.41208791208791%; padding-bottom: min(75.41208791208791%, 549px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-549-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 549px; } I think this is because Cavett wasn’t like those other guys. “Cavett facilitates,” writes Christina Newland, fellow Cavett stan, “wry and unassuming, chairing gatherings that have the intellectual air of an old-school Parisian salon.” Though he talked often about being a comic, he was not an entertainer, like Carson. Though sometimes provocative or combative, he was not a provocateur, like Howard Stern, nor a pugilist, like Letterman. He was not an edutainment hack, like Jon Stewart or Colbert, nor a babysitter, like Jimmy Kimmel, nor a plant, like Seth Meyers, nor a dead-eyed consent manufacturer, like Jimmy Fallon.

No. As Esquire writes, he was a conversationalist, and while he wasn’t always as successful with his guests as he was with Burton, he cultivated something that it’s easy to feel nostalgic about, even if you weren’t alive to see it. Like many of us, I’ve spent the pandemic yearning for Before. As Newland writes, “Watching his show now, cooped up, makes me yearn for the days of public intellectualism, when the contrasts between people were celebrated for producing the most striking and engaging discussions, rather than manipulated and exploited for entertainment.” I think I disagree with the mythologizing inherent in her claim, but I feel, very deeply, the emotion from which it stems.

But more on that next time.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022).

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

Subscribe & Support Mutual Aid

1The star of her own interviews and to whom we will return over the course of this series.

2Often cast as a Roman onstage, Burton reminds Cavett’s audience that his native Welsh is deeply influenced by Latin, the language of Britain’s old conquerors.

3And today you can find them on Twitter.

4Or maybe it’s better to be specific with the red kite, the national bird of Wales.

January 1, 2022

David Davis

a.image2.image-link.image2-400-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 54.94505494505495%; padding-bottom: min(54.94505494505495%, 400px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-400-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 400px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-400-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 54.94505494505495%; padding-bottom: min(54.94505494505495%, 400px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-400-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 400px; } When I thought to join everyone in ranking the books I read in 2021, my list reminded me that Maurice was among my favorites1. E.M. Forster’s novel of homosexual love in Edwardian England, which was not published until after his death in 1970, is notable and unique for its happy ending, on which the great author refused to compromise. Forster’s “posthumous novel of gay life,” as Alexander Chee describes it in one of last year’s standout essays, follows the eponymous homosexual in his desperate struggle against the “unspeakable vice of the Greeks.”

In its attention to detail, Forster’s portrait of a young man’s developmental trajectory from innocent to lover is as painstaking as the removal of orthodontia, and yet as joyous as public sex. When he meets Clive, the agent of his first heartbreak, Maurice spends the night pacing the lawns of Cambridge, “his heart glowing.” Though the following morning, and for the next few years, he will compartmentalize his desires from his gender, race, and class obligations, Maurice’s “heart had lit never to be quenched again, and one thing in him at last was real.”

This flame stands him in good stead in conflicted Clive’s kissless purgatory, in the physician’s hostile exam room, in the hypnotist’s sterile oblivion: Maurice goes on to find Alec, the upper-class Clive’s groundskeeper, and Alec finds him, in return. “He knew what the call was, and what his answer must be. They must live outside class, without relations or money; they must work and stick to each other till death. But England belonged to them. That, besides companionship, was their reward. Her air and sky were theirs, not the timorous millions’ who own stuffy little boxes, but never their own souls.”

The publication of Maurice was a coda: as text, with its articulation of the unspeakable (including that for which Forster, personally, could have gone to prison); and beyond, with an afterword contextualizing the author’s creative decisions: “I was determined that in fiction anyway two men should fall in love and remain in it for the ever and ever that fiction allows, and in this sense Maurice and Alec still roam the greenwood.” As real as their world feels to me—who among us has not had to choose between our souls and a closet-case?—Maurice the modern novel concludes as fairytale, with the two lovers disappearing into an England where “it was still possible to get lost,” as the author writes. Following two world wars, “the wildness of our island…was stamped upon and built over and patrolled in no time. There is no forest or fell to escape to today.”

Though Maurice and Alec get their happy ending, modernity keeps on its inevitable grind, in a process of attrition rather than progress. “We had not realized that what the public really loathes in homosexuality is not the thing itself but having to think about it,” Forster wrote in 1960. The ruling class would maintain control through, in part, the criminalization of free sexuality: “Clive on the bench will continue to sentence Alec in the dock. Maurice may get off.” Though we must be suspicious of our separatist impulses—which, uninterrogated, replicate those same hegemonic structures we wish to flee—Maurice and Alec’s alternative to assimilation, even if imaginary, is what saves Maurice from obsolescence, even here, even now.

I’ve begun 2022 with another novel about (homo)sexual outlaws. Lucy & Mickey, American author Red Jordan Arobateau’s “butch trip through life before Stonewall” is worlds away from Maurice in subject matter (impoverished butch/femme dykes hustling to survive in late-1950s Chicago), style, perspective, and reception. But it shares with Maurice an insistence on pleasure as truth, as real, though for queers it can only take place outside of real life.

In opposition to that real life, to the nuclear family, straight jobs, white supremacy, and the cages of foster care, mental ward, and prison, Lucy & Mickey’s main characters live the Life, the extralegal existence relegated to the poor, the drug-using, the sex-working, the gay and transvestite, the black, brown, and indigenous. So long as Arobateau’s protagonist, teen butch dyke Mickey, chooses the Life over straightness, she will never really be a citizen, fighting to survive the great apathy of “the shops and factories that didn’t want to hire her. Restaurants and bars that didn’t want to serve her,” and the more targeted threat of the police state.

But together with Lucy, the femme she meets while turning a trick to save herself from starvation, Mickey can find her own greenwood, steal “a piece out of this insane world with its trade & its freaks.”

“It’s a dangerous world out there. Dangerous to the heart,” Mickey thinks to herself. Like Maurice’s flame, the heat of her lust keeps her warm, if not safe.

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022), here.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

Subscribe & Support Mutual Aid

1It was one of three Forsters I read last year, alongside Where Angels Fear to Tread (biting but homey) and Aspects of the Novel (trippy as fuck).

December 26, 2021

David Davis 37, Part 1

a.image2.image-link.image2-660-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 90.65934065934066%; padding-bottom: min(90.65934065934066%, 660px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-660-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 660px; }

a.image2.image-link.image2-660-728 { display: inline; padding-bottom: 90.65934065934066%; padding-bottom: min(90.65934065934066%, 660px); width: 100%; height: 0; } a.image2.image-link.image2-660-728 img { max-width: 728px; max-height: 660px; } Has someone ever made you feel as if you were the most interesting person in the world? Though most of us are neither Joe Exotic nor Raven Leilani, we enjoy, now and again, indulging in the fantasy that we might someday join their number, that we’re one lucky break away from real recognition—an It Girl in the making, an influencer on the rise, an undiscovered genius vibrating in the wings.

The ability to make other people feel interesting belongs to the same kingdom as the ability to tell stories. I’ve met raconteurs, too, but their magic trick is more obvious. The Storyteller holds you in thrall, spinning yarn on the the knife’s edge of credibility. I’m thinking of an acquaintance who seems to live in a telenovela, always with a semi-legal caper, near-death experience, or absurdist breakup to share as she works her way through her pack of Marlboro Reds. She is a Storyteller because she can convince me, for a few breathless minutes at a time, that she is the main character. While her math may not always add up (Wait a minute, I thought you said that the cop went home with the meth-dealing performance artist?), my skepticism never outweighs my entertainment.

The Interlocutor, meanwhile, casts Main Character Syndrome upon you like a spell. Intoxicated by their attention, your fallback anecdote, secret grudge, or bland trauma suddenly become worthy of analysis, laughter, and commiseration. You find yourself revealing more than you ever though you would, confident in the Interlocutor’s thoughtful but unobtrusive goodwill. Is it authentic? It doesn’t matter. “My only advantage as a reporter,” wrote Joan Didion, whose death last week prompted a bunch of her quotes to recycle their way through through Twitter again, “is that I am so physically small, so temperamentally unobtrusive, and so neurotically inarticulate that people tend to forget that my presence runs counter to their best interests.” What makes a good Interlocutor? You never see them coming and they leave without a trace.

We all have Interlocutors, of various levels of skill, in our lives. They are the historians, the gossips, the nurturers, the middle children, the conflict-averse, the fawners who’ve figured out how to hide in plain sight. I’ve no wish to pathologize—some people are simply curious—but I’m fascinated by the Interlocutor-type who wants none of my fascination, who strives not just to redirect attention from themself, but to control it entirely, rationing it out like a key-ringed steward. Appraising both subject and audience with learned perspicacity, in total control—or so they like to think—this Interlocutor-type only seems averse to the spotlight. They actually quite like it, provided that they’re running the board.

If I sound critical, it’s only because, as a writer, I’m deeply envious of the Interlocutor’s power to expose others while disclosing nothing of themself. Tempted by the discursive immediacy of online, I sometimes succumb to the fantasy of writerly tease-and-denial: that I am controlling my readers, rather than interesting them, being in conversation with them, or telling them a story. But then I remember that I am here to communicate, not to obscure. As someone who writes for a living, I must do my best to prevent this transactionalism from seeping into my art. Just because we must work within the attention economy doesn’t mean we need be defined by it.

Nevertheless, there’s much to be learned from the Interlocutor as artist and artisan. At its best, this rare and pleasurable talent pinpoints the narrative ore in a continent of content. This DAVID series will feature my favorite interviewers as a dissection of the interview as mode, craft, and object d’art: How does the Interlocutor convince1 their audience and their subject that the latter is the most interesting person in the world?

David tweets at @k8bushofficial. Preorder their second novel, X (Catapult, 2022), here.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, an advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

Subscribe & Support Mutual Aid

1Or trick

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 55 followers