Davey Davis's Blog, page 17

December 27, 2022

David Davis 40

Unbelievable as it sounds, there are aspects of my personal life that never make it to the internet.

I understand why this may be surprising. For one thing, the general conflation of public and private for feminized people means that my fiction is more closely associated with the real me than it is for other kinds of people. For another, my candidness on Twitter and IG likely lends to the impression that no filter exists between my life and its digital render. Of course, this is an illusion with which all of us who have social media must negotiate. To exist on an increasingly privatized internet is to be a product (one that can never be totally self-managed) to be marketed, whether or not we ourselves are selling something (though I certainly am, and not just subscriptions to this very enriching and charming newsletter).

Open as I may seem, I am calculating about what I share with you here, whether it’s about my sex life, my natal family, or my art. It would be a lie to say that my calculation isn’t informed by my bottom line, but for the most part it comes down to a question of my own, perhaps idiosyncratic, notions of vulnerability. In this world where my nudes are online, my sex change has been documented, and my identity, likeness, shopping habits, and location are available to the highest bidder, my idea of personal may be unorthodox, but rest assured it’s intact. It includes my romantic relationship with my lover, or the parts of it that comprise what’s most precious to me (and likely most boring to you).

Still, the boundary between public and private is not impermeable, and occasionally crossing it can be helpful in illustrating a point.

Lesbian processing is an extreme sport. This occurred to me after a recent conversation with Jade about sex, leather, and our relationship; in essence, about how we talk to each other. The conversation was a successful one, but due to its duration and intensity (and the makeup sex that followed) it was a good example of what we usually mean by lesbian processing, an epithet informed by stereotypes about women in general being overemotional and queer women in particular placing a hysterical, unscientific, and unsexy level of importance on communication; this being set in opposition to normal heterosexual relations, which happen without anyone having to think, without there even needing to be consent, because these relations are natural and unchanged and unchanging since forever.

When you’re a dyke, your fate is to always be seen as either utterly ridiculous or an ugly threat. I’m old enough now to have a sense of humor about lesbian-specific things—from bed death to dyke nods—that I’m supposed to feel ashamed of. As with the other stereotypes, lesbian processing is something that we dykes often poke fun at ourselves, but I think that the humor limns what should be a goal for all intimate relationships: regular and honest communication among equals. When done correctly, processing, lesbian or otherwise, is a tool for deepening connection and intimacy. Having the opportunity to say yes as well as no, to negotiate and to compromise, to share as well as to maintain private. Outside the four walls of a corny joke, lesbian processing is a cog in a communication style, one that fosters the trust that Jade and I need in order to do a lot of fun things together and separately while also being, as a friend said recently, the “most monogamous non-monogamous couple” they know.

The physical and mental exertion. The sweat and the tears. The gender non-conformity. Lesbian processing is an extreme sport. This is not an original thought. It’s probably on a snapback somewhere, or on a bumper sticker in Portland, or scrawled on the bathroom wall at Eli’s in Oakland or Ginger’s in Brooklyn. But platitudes are platitudes, and as it bubbled up, it collided with another thought that I’ve been mulling recently: that the social activities requiring the most communication, willingness, and consent are the very same that straight culture and its institutions take great pains to forbid us1.

It’s tempting to follow this thesis to its converse, especially for someone who, like me, abhors a power vacuum. I could suggest that the social activities requiring the least cooperation—the ones that are executed in a manner that’s unthinkingly rote at best, that are promoted, normalized, and ultimately socially, economically, and legally enforced—are actually the least consensual. I could locate the coercion in the acts themselves, rather than in the dynamics wherein they take place. I could position the mechanism of heterosexual sex as inherently violent, as if it were a static, graspable thing instead of a fluid intangible, much like we like to say about our own genders and sexualities.

But for my benefit as much as yours, I will insist on an alternative: that there is no sex act or actor that is inherently safe or dangerous, and that an outsider looking in cannot know better than the insiders do.

In my first book, the earthquake room, one of my characters echoes an observation that I’ve long held close for myself: “if straight people have something to say about us at all, they’re probably wrong. in fact, the opposite of what they say is probably true.”

This idea has been a sort of anti-internalization spell since I was a young gay, and I still rely on it all these years later. When I’m told that lesbian SM is patriarchal, or that drag queens are groomers, or that fisting is violent—ancient, rust-jointed canards you’ll hear just about everywhere, from liberal LGBT types to right-wing politicians, from radical feminists to Christian fundamentalists—I have trained myself to first consider the source before deciding to believe. I don’t even really need to be told these things. They’re felt and known in the body, the way you’d feel the current of a river if you walked the floor against it.

Because not only are SM, genderplay, and queer-coded sex not inherently violent2, but when done successfully they require total collusion from all involved. Vaginal fisting, for example, is a queer-coded sexual practice that is widely regarded as risky, and even dangerous, when—as with other kinds of penetration with other objects and holes—risk and safety depend on a constellation of factors, one of them being the bottom’s level of sustained arousal3. It's often framed as an edge case, as inaccessible to most “normal” people, even to gay people, when it’s actually an activity that I think many, if not most, can participate in (as tops if not as bottoms) with just a little knowledge, practice, and patience—and not even that, sometimes. As I tweeted a while ago, the first time I fisted someone vaginally, it was almost by mistake, because some people can be fisted easily, even as others struggle to take the average-size penis, or dildo, or even a finger or two.

But as we observe in contexts where sexual censorship meets capitalist commerce in a culture that hates women, gay people, and pleasure, fisting is positioned as inherently obscene, unsafe, violent. Just ask anyone trying to post content on sites like OnlyFans that use vague or subjective language to circumscribe activities like fisting, roleplaying, or gaping, which not only further stigmatizes sex work and consensual sexual activity, but relies on normative definitions of extremity to pick and choose which content creators are censored, and therefore economically deprived.

Just as prostitution is made dangerous by criminalization, or our society ableist because it’s designed to be inaccessible right down to the handlebars and street curbs, the sociocultural conditions in which we find ourselves are intentionally hostile to life, meaning they’re intentionally hostile to connection. The more time, effort, and attention a sex act requires, the more difficult it is. I won’t say that a kiss (or a blowjob) requires less connection than a fistfuck, but it does require less overhead (to use a capitalist term), and that’s before we even factor the identities of the kissers (or whatever) involved.

Lesbian processing is an extreme sport. Being both gay and non-monogamous puts me at heightened risk of being annoying. Like vegans or those who use they/them pronouns, the non-monogamous have a reputation for sanctimony and condescension meant to conceal the flaws in a less-than-peachy romantic relationship. I’m not interested in pretending that Jade and I don’t have to deal with jealousy, or insecurity, or hurt feelings, not because I mind lying but because I think it’s silly to aspire toward perfection that doesn’t exist (especially because its puncture is more humiliating than the failure to reach it in the first place). But I don’t think romantic relationships have to be hard, or any harder than any other kind of relationship, and my relationship with Jade isn’t hard at all. It makes my life better and easier. That’s why I’m in it with her.

When our friend made the cheeky comment about us being the “most monogamous non-monogamous couple,” it was a kind of joke. Like the notion of lesbian processing is a kind of joke. A relationship style, like a communication style, takes place over time. It can be cherrypicked for absurdity or failure or even a punchline, but when it becomes its own kind of normal, farce loses its steam. I guess what I’m trying to underline here is the difference between normal and everything else, and how very rarely we take the time to examine why one is one and not the other.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

1Straight here is, as I use it, understood as more capacious than mere heterosexuality. Straight is white supremacy, imperialism, carceralism, and capitalism. It’s anti-queer and trans, anti-woman, -child, and -elder, anti-black and -indigenous, anti-whore, anti-sick, anti-crazy, anti-poor, anti-migrant and -refugee.

2I recognize that some of us in leather have reclaimed the idea of violence, in the same way that some of us have reclaimed slurs; for the most part, I’m one of those people. This is not a rebuttal of that reclamation. What I’m trying to do here in tandem is re-examine the conflation of violence and violation, to decouple a range of sensations from retrograde notions of consent. Just because something feels good doesn’t mean it’s consensual (see the footnote below); just because something causes pain doesn’t mean it isn’t. As if pain and pleasure are even that easily delineated, anyway!

3I should note that arousal does not necessarily constitute consent.

December 17, 2022

David Davis

Between work, this newsletter, my novels, my lover and friends and hobbies—being alone, yoga, running, sex and violence, dancing—I’m a busy girl. Every December, I resolve to spend less time on Twitter and more in bed (alone) with a book, and every December I look back on the past year with not a little regret.

This December, I’ll allow myself some rationalization: for the most part, the books I read this year were challenging, enriching, diverting, and beautiful. A few are still in process (Dancer from the Dance by Andrew Holleran, Palo Alto by Malcolm Harris, and The Passenger by Cormac McCarthy). Some were began but never finished for reasons outside my control (Sam Delany’s About Writing was lost to summer depression, and anyway it had to go back to the library), others because they were not at all pleasurable to read (Jordan Castro’s The Novelist, Anita Brookner’s Hotel du Lac). I even discovered, to my heartbreak, a Manuel Puig that I not only didn’t adore, but couldn’t stomach: his first novel, Betrayed by Rita Hayworth.

DAVID is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

I don’t include near-misses and abandoned ships in my final count, but if the point of these end-of-the-year lists is to peek over the shoulder of our parasocialites, they give a fuller sense of how I read, if you’re curious about that: messily, sporadically, furiously, judgmentally (if not always critically). Jade says that when I’m obsessed with a book I spend a week or two talking endlessly about how its author is Just like me!, whether or not they are and whether or not their work resembles mine; I think this sensation is the closest I get to feeling seen, and delight in knowing that this recognition has very little to do with the liberalism’s CVified identity politics. That’s the power of literature, baby! If an artist is doing their job, I fall in love with both of us.

Anyway, here’s what I read this year. Wish me luck for a more readerly 2023!

Cataracts, John Berger

In the Cut, Susanna Moore

Heat and Dust, Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness, Da’Shaun L. Harrison

Tell Me I’m Worthless, Alison Rumfitt

Pig Earth, John Berger

Candy Darling: Memoirs of an Andy Warhol Superstar, Candy Darling

Palmares, Gayl Jones

How to Write an Autobiographical Novel, Alex Chee

Sensational Flesh: Race, Power, and Masochism, Amber Jamilla Musser

The Continuous Katherine Mortonhoe, D.G. Compton

Civilization and Its Discontents, Sigmund Freud

Bad Gays: A Homosexual History, Huw Lemmey and Ben Miller

How Far the Light Reaches, Sabrina Imbler

Gargoyles, Thomas Bernhardt

Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World, Wil Haygood

My Cousin, My Gastroenterologist, Mark Leyner

What Belongs to You, Garth Greenwell

The Big Goodbye: Chinatown and the Last Years of Hollywood, Sam Wesson

Brother Alive, Zain Khalid

Couplets, Maggie Millner

Limbic, Peter Scapello

Death in Venice, Thomas Mann

Shuggie Bain, Douglas Stewart

At Certain Points We Touch, Lauren John Joseph

See you next year. Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

December 12, 2022

David Davis

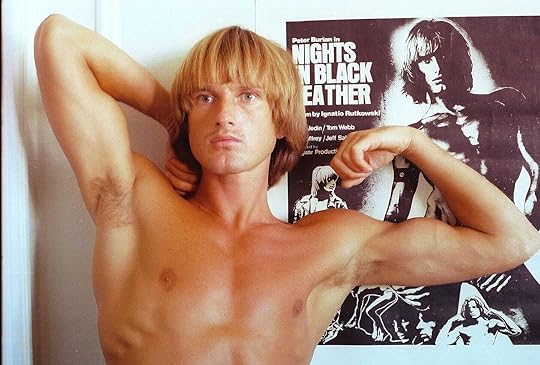

A beautiful young man strolls through a field of white flowers—perhaps one of the many clearings to be found in San Francisco’s byzantine Golden Gate Park. Our beauty encounters another beauty, though this one is nowhere near as beautiful as our original, a truth we gather less by comparison than by the composition of the shots; the actors’ wardrobes; and the way the camera follows the slow, almost contemplative movements of our anointed one. As the other watches, the beautiful young man undoes his skintight leathers to stroke and climax from among the fallen white flowers, surrounded by the violins of what’s known colloquially as Pachelbel’s Canon.

When Peter Berlin’s That Boy was filmed in the early seventies, Johann Pachelbel’s “Canon in D Major” had not yet become the anthem of weddings and college graduations. Sweet yet plodding, its growing popularity since the 1980s has turned the canon into the West’s aural shorthand for major life events that are serious but rote, sentimental yet unfeeling, normal and yet far from natural. One may suspect that the bridal tenderness the music imbues That Boy is an intentional juxtaposition with its hardcore gay sex, arthouse plotlessness, and leatherfuck1 finale2, but I like to think otherwise.

Philosophical, romantic, imaginative, comical (though whether that’s intentional is also unclear3), and ultimately transcendent, That Boy encapsulates the mythos of Berlin, legendary muse of Mapplethorpe and Warhol and pre-internet “photosexual” whose documentation of his own beauty “gave a world starved of blatantly gay visual role models a new conception of the beautiful, empowered, self-loving, sensual, shameless gay man.” As his alter-ego, Helmut, Berlin struts Lou Sullivan’s Polk Street (now gentrified into oblivion), where he is observed by all with the fascinated adoration of his park cruise. In art as in life, Berlin is his own fantasy, too4: “Every guy I meet is in competition with myself. I get into my persona. I look at myself; I have sex with myself.”

As art, and particularly as pornographic art, That Boy collapses fantasy with the stylization of a real man’s life that is and remains, by all reports, utterly dedicated to cruising. While he has called the camera his “dream lover,” Berlin’s artistry does not, cannot, supplant the reality of his body among other bodies. “Real for me,” he told Aperture a few years ago, “is when I walk the streets and you pass me, I look at you, you look at me, we pass each other, and then I look back, and you look back, and you stop. That’s real! That will never happen inside a computer.”

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

1I don’t want to fail to acknowledge that a few explicit Nazi symbols appear in That Boy, much of it on the leather regalia of the final scene. While Berlin’s provenance—he was born to a well-off German family in Nazi-occupied Poland in 1942—is not immaterial here, military, police, uniform, fascist, and, indeed, Nazi symbolism have never been uncharacteristic of leather subcultures in the USA. I’ve written toward these connections before, but I’m far from any kind of authority on them.

2Contrast it, too, against the UX of whatever porn aggregator where you view it. (I don’t recommend using those, but I’m not going to pretend it isn’t available there!)

3“There's a comic tinge to his eroticism,” writes Armistead Maupin. “[H]e's too preposterously doll-like to exist. I think of him as the Bettie Page of beefcake.”

4Although at one point in That Boy, Helmut meets a blind man who, as the only person immune to his glamour, joins his near-solipsistic fantasy of himself. (Cringe!) As Berlin told W in 2019, “I was always very visual. I get my whole information through my eyes.”

December 7, 2022

Your favorite DAVIDs of 2022

Below you’ll find DAVID’s most-read posts of the past year, plus my favorite series, which didn’t exactly rank with you all but which was, I think, some of my most solid writing.

And by the way, thank you for reading in 2022! It was a pretty big year for me. I said hello to new experiences and goodbye to GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY. I reviewed books, movies, and flavors. I made a case for girlfriends and against intelligence. For my non-DAVID writing, I published my second novel and almost nothing else, other than an essay on a documentary called BloodSisters: Leather, Dykes, and Sadomasochism for the short-lived Astra Magazine (RIP).

It’s fair to say I’ve been quite productive this annum, but I feel as if I haven’t really flexed yet. With any luck, I’ll have something to show for myself soon. Until then, this newsletter will keep coming out more or less weekly. I hope it’s nice for you. It is for me.

1. On the gangbang2. An interlude on heteronormativityIf America’s incest fantasy could be peeled apart, like a banana, the fruit inside would be thick, sweet, and less convincingly phallic than its exterior might suggest. My theory is that the substance of this edge fantasy is an intimacy that can be taken for granted. Imagine.

3. A hookup yields reflections on trans life[W]hile drunkenly fooling around in a car with some straight guy, I became too distracted by what he looked like to fuck; instead of getting angry or pressuring me, he listened while I talked at length about much I wished I had his body (?!?!), then drove me to a Jack In The Box and bought me food to soak up the booze. I’ve always looked back on that experience with gratitude—he was kind to tolerate my strange behavior, and he didn’t even try to rape me. Only relatively recently did I understand what was actually going on between us, or between me and his body, anyway.

4. “Gender is not my boundary”This is also fascinating to me: the chaser who can’t learn the language he needs to get the pussy he wants. From the couch, I peer into his wife’s office, where a Peloton twists in the shadows like a dozing xenomorph. I suppose a chaser like Max doesn’t have to learn anything he doesn’t want to.

5. On going underThere was a popular meme, for a minute there, that non-binary people were sharing that said something to the effect of If you’re attracted to me, you’re gay. Which, if that’s your experience of yourself, sure, fine. But I’m much more interested in the challenges of maintaining what are, for most of us, deeply held understandings of our own genders and sexualities when they are fundamentally incompatible with those with whom we vibe and fuck. How can straight people and gay people have sex? It happens all the time! How can dykes fuck fags? Literally every day. How can one be a monogamous sex worker? Easily! How can your identity not invalidate mine when our bodies push against each other? I don’t know, but it can!

6. Let a thousand fisting daisychains bloomHe struggled to convey what it was about golden showers that he liked so much, and why they brought him to what was essentially a brothel, rather than to the feet of an open-minded girlfriend. This mystifying urge left him both verbose and inarticulate, as our deepest erotic desires do for most of us; though he was no poet, G’s passion, which he was happy to leave more or less unexamined, felt poetic to me.

7. An interlude about straight peopleTo say that the deviant subjects produced by white supremacist patriarchy are welcome at Pride so long as they don’t use it to indulge in deviance is to contradict oneself. They’re already deviant because they exist.

8. Can I smell this public rose? Can I smile in the street?As a result of this penchant for taking out the trash, I’m one of those lucky gay people that has had very few heteros in their day-to-day life for many years. It’s not my intention to be categorical, but since I won’t tolerate disrespect from someone who’s not paying my rent…well, you know how straight people are.

9. An interlude on craft, work, and fantasyI looked out the window, where below me a cumulus shelf of orange sherbet witnessed our howl to New York City. No one could see me crying, but what if they did? I think it would be okay.

10. On Dick Cavett and the art of the interviewThough I’m fundamentally repulsed by his prioritizing of style and structure over “the great idea” (which he called “hogwash”), my dear Nabokov’s dedication to component can be read as another kind of subversion. “Caress the details, the divine details!” he urged, which dictum we can reappropriate for our anti-work perspective: what is work if not effort with a capitalist agenda, rendering pleasure incidental?

We all have our special interests. Mine happens to be a problematic nonagenarian talkshow host that my girlfriend refers to as my “interview man.”

I don’t remember why I started watching episodes of The Dick Cavett Show on YouTube, but suddenly it was a part of my solitary nighttime ritual, the hour or two before sleep when I laid down on my mom’s yoga mat, chain-smoked joints, and anticipated another 16-hour-day of muting C’s screams over Zoom meetings while trapped indoors by viral plague and fire season. Delighted by the seemingly endless roster of famous subjects—including Salvador Dalí, Katharine Hepburn, Judy Garland, Miles Davis, Muhammad Ali, Marlon Brando, Orson Welles, Lucille Ball, Truman Capote, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Richard Pryor, and my beloved Sophia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni—I found myself entranced by the pedantic patter of this boyish Midwesterner, who over the course of almost 40 years of hosting his self-titled talk show has aged from Pinnochio-esque whippersnapper to batty examiner emeritus.

See you next year. Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

December 1, 2022

DAVID: Members only

Though it offers a steam room, a sauna, and bodywork services, Oakland institution Piedmont Springs is best known (among my old milieu of Millennial punks and queers, anyway) for its private outdoor hot tubs.

Wedged between a garden store and a bookshop, the spa’s shabby foyer leads to a wood-paneled corridor, beyond which are the patios that are so popular you should aim to book a week in advance. Hang your bag on one of the wall hooks and, once your escort closes the door behind you, strip down and surrender yourself to the caldera. If clouds bruise the square of sky above, it’s easy to imagine that you’re cloistered in the core of a Pescadero yurt, the air piquant with sequoias and sea salt.

From Berkeley’s women-only backyard nude tub with the hottest temps I’ve ever braved; to gay bathhouses like Steamworks and Eros; to the geothermal pools scattered throughout the Bay Area, there are plenty of local institutions distinguished by their potential for sweat and anonymity, but Piedmont Springs is probably my favorite. You can go with your friends to shvitz. You can go with your dates to fuck. You can go with your regular because, for the price of $27 per person per hour (though I think it was cheaper, back in my day), it’s one of the most convenient places for professional piss play outside of a private residence.

Discreet and relatively inexpensive, with minimal cleanup—there’s a shower in the corner and drains in the concrete floor—you can work with the sun on your shoulders and a jet massage as consolation prize if your client no-shows. Not that G ever did.

November 30, 2022

David Davis

MICHELLE HANDELMAN, 1995. PHOTOGRAPH BY J.C. COLLINS.

MICHELLE HANDELMAN, 1995. PHOTOGRAPH BY J.C. COLLINS.With the recent announcement that the newly-launched Astra Magazine is not long for this world, I thought I’d re-share “Pain is the Point,” which I wrote for them about Michelle Handelman’s film, BloodSisters: Leather, Dykes, and Sadomasochism (1995), over the summer. Featuring my friend Daemonumx, femme4femme torture, the feminist sex wars, and fist-fucking, “Pain is the Point” is a sentimental piece about an important film, one to which I’ll surely return in the years to come. Even if you don’t read my essay, see this movie. It’s worth it.

Just so this post isn’t entirely self-serving, I’ll note that this essay was edited by the illustrious Spencer Quong, a sharp and thoughtful reader that I recommend to any writer.

All right, then. As you were.

Want exclusive DAVID content? Paid subscribers help me pay off my student loans & earn my undying love.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

November 22, 2022

David Davis

Max, surname “Grindr,” is in my phone, but our short message history doesn’t tell me much about him. He claims that we’ve already met—Before I went to Barcelona, remember? I don't. My recall can’t be trusted, and I’m pretty slutty, but because I like to record things I have a spreadsheet of people I’ve slept with recently, and Max isn’t on it.

Instead of blocking him, however, I admit that the possibility that he’s lying is kind of hot.

I'm honest, Max promises. It's probably my sole virtue.

He sends me a photo of his cock and it’s big and pretty, so I decide to see what happens.

My doubts are confirmed when I arrive at Max’s Upper West Side apartment building. Even my THC-addled brain would remember a place like this. It’s new, built in that boxy, trendy style that you can see for yourself if you Google “gentrifier architecture.” A man in a suit hustles to open the door for me, then makes a phone call. A second suited man is seated at an island at the end of a glass corridor, beyond which is a landlocked garden with a redwood deck. Though he watched the first doorman make his call, the second screens me, too. At the top of the elevator and down a hallway, a short middle-aged man that I don’t recognize answers my ring. He is wearing a plaid button-down over khakis. He smiles.

Max is not attractive, but I didn’t expect him to be. He told me he was “ethically non-monogamous,” so the only reason he wouldn’t send me a photo of his face is that he knows it can’t do the heavy lifting his dick can. But it’s not so much his appearance that I don’t like—that ranks fairly low for me, when it comes to these things. It’s his demeanor, his vibe. Ushering me into a foyer that’s half the size of my own apartment, Max is politely apologetic, and not interested, seemingly, in convincing me to stay. As I look around, I realize why.

I start removing my coat, spinning on my heel to take it all in. There’s unblemished marble and unsmudged steel. The appliances, Scandinavian and Japanese, are brand-new. Whoever cleans the place obviously doesn’t live here. I see, from the corner of my eye, that Max is watching me. By the way he holds himself—tensely, as if waiting for the Russian judge’s decision—I can tell there’s room to be bratty.

I’ve never seen you before, I announce, tossing my things on an upholstered chair the color of ivory and cream and the shiny side of tungsten.

I guess not, Max says, still smiling. His glasses have thick, black frames. I thought you were someone else.

I laugh at him. Another t boy?

I was going to offer you a drink, Max feints, but why don’t I give you the tour first?

Even New Yorkers use this expression, even those who don’t have more than a room to call their own. This is not the case for Max, whose apartment, glass-walled like the lobby below, has two offices, three bedrooms, and a stunning view of the River. Any single piece of furniture costs more than my rent, or at least my student loan payment. The walls are full, though not cluttered, with vast paintings and prints. As we move through the apartment, Max recounts the origin and value of every piece, with a smattering of boorish detail. Have you heard of so-and-so? He painted this before he killed himself. The art, most of it reminiscent of Basquiat and Banksy, is, without exception, hideous. One painting features Donald Trump with a ball gag in his mouth and graffiti-esque squiggles around his body.

When we return to the open kitchen, Max announces that he’ll make me a Negroni (hold the Prosecco), taking care to explain to me what exactly that is. I know what I look like to him, in my crop top and piercings. I think of the little white trans boy he mistook me for, and wonder how old he is.

We take our drinks to a circle of Eames chairs, where Max tells me about his homes in Maine and the aforementioned Barcelona; I half-expect him to ask me if I’ve ever heard of it. When he stands and turns to dim the lights, he exposes his cheap, ill-fitting boxer shorts. He won’t tell me what he does for a living—or used to do, since he retired years ago—but says he divides his time between consulting for a nonprofit and writing books. He is coy about what consulting means, as he is about the books, although, he says slyly, they both did quite well.

And what do you do? he finally asks, seizing his Negroni from its makeshift coaster, a copy of Artforum.

I also write books, I tell him. He Googles my new novel. A New York Times Editors’ Choice! He almost hollers it. Oh, fuck you, David!

Max is impressed and sheepish; his evening has taken an unexpected turn. I take a big swig of Negroni. It tastes great.

We talk some more, which is to say, I listen some more. He tells me about his wife, his adult children (who he believes are older than I am), the sex positive community he was once a member of in San Francisco (but you're too young to know what that is). Max is under the impression that his sexual lifestyle—polyamory, group sex, gay sex, casual sex—is a recent development made possible by the creation of a “market” by hookup apps. When he tells me that older men, like him, couldn’t find beautiful young boys, like me, before Grindr, I laugh in his face. He laughs with me, looking more confused than pained.

Still, he senses that I’m having a good time, and I can’t say I’m not entertained. The Negroni starts to hit and the apartment is warm. All is going well. Max starts putting the moves on me in the most juiceless way imaginable.

You're so fabulous, he says. Now we’re on a couch together, our empty glasses abandoned in a different room. I find you so incredibly appealing.

I find him fascinating, if repulsive. I don’t want to have sex with him, but I do want to see if I can get things out of him, this wealthy man who seems inclined to generosity. It’s a fun game. He asks me my age, and is shocked to learn that I am, in fact, older than his adult children. The transsexual he had me confused with was 19. In comparing us, he struggles to describe the trajectory of our transitions, though of course I did not ask him to. This is also fascinating to me: the chaser who can’t learn the language he needs to get the pussy he wants. From the couch, I peer into his wife’s office, where a Peloton twists in the shadows like a dozing xenomorph. I suppose a chaser like Max doesn’t have to learn anything he doesn’t want to.

In the interest of keeping my options open, I decide that I won’t have sex with him, but that I will let him cum. I take my clothes off, and Max admires me while I stroke the shaft of his big, pretty cock. I know what you like, Max says, affecting an unnaturally deep voice. He wraps his fingers around my throat. He doesn’t have a strong grip, so his bad form isn’t dangerous. I repress more laughter. (I wish that this sort of thing wasn’t fun, but it is.)

When he cums, and he cums quickly, Max emits a loud, abrupt scream. Remember that (maybe apocryphal) viral video about a group of scientists who recreated the voice of a mummified neanderthal and it’s hilarious? That’s what he sounds like. As his blood pressure returns to normal, he gazes up at me, squinting a little without his glasses. I await more compliments, or else more demands. Instead, he asks me why the Times chose my book. He’s still catching his breath.

I’m caught off guard. But I tell him why they chose it, or why I think they did, anyway. I’m still wondering if I’m even close to right when then Max says something else: that trans kids shouldn't get to transition until they're at least 18.

Only the day before, the most recent transphobic hit piece from the Times, this one about the “dangers” of puberty blockers, had rocked Twitter, the platform itself newly acquired by a billionaire transmisogynist who’s since reinstated a bunch of banned accounts, including Trump’s. Max’s projection is obvious to me—put the tranny faggot in its place, while insisting on the clockiness that is clearly more to his erotic tastes—but I can’t escape the coincidence. How can I, with the Times’ audience right here with me, a liberal with cum on his belly and Campari on his breath, a rich white straight man—I don’t care who he fucks—with everything to lose and nothing to fear?

No. I don’t care to argue with him, but it must be said. You’re wrong.

Realizing his mistake, Max attempts to explain himself. He tells me about a trans girl whose family he knows. Her parents did not permit her to medically transition until she was 18, and she turned out just fine, he insists. He misgenders her until I correct him. It’s difficult, I think, to balance dominance with satisfaction.

Kids die because of that mindset, I say. There’s nothing else.

Only kids from bad families! Max retorts.

The game is over. I used to mock women who had sex with men for free—who’s the loser now? I go back to the living room for my clothes. Max is still talking about the girl who is now beautiful and happy and surged up, intercutting her story with fantasies about fucking me with his cis boyfriend, who’s 24 and, according to him, has a long, skinny dick. I wonder how much he pays the boyfriend. A lot, I hope.

Max insists on getting me a car home. He shows me his phone, proving that he’s ordered a copy of my book. Now that the balance has been restored, he is generous again.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

November 17, 2022

David Davis

I identify more strongly as a sadomasochist than as a lesbian. I hang out in the gay community because that’s where the sexual fringe starts to unravel. Most of my partners are women, but gender is not my boundary…If I had a choice between being shipwrecked on a desert island with a vanilla lesbian and a hot male masochist, I’d pick the boy. This is the kind of sex I like—sex that tests physical limits within a context of polarized roles.

If it seems like I quote Patrick Califia’s “A Secret Side of Lesbian Sexuality” in every other newsletter, well, can you blame me? Like Alex Chee on E. M. Forster, Kim TallBear on sex and family, Astra and Sunaura Taylor on animal liberation, or Patricia Lockwood on Vladimir Nabokov, Califia on desire is, for me, a long revelation. Each time I return to this essay, it revitalizes me, as the backs of shampoo bottles like to say. If I step away for a few years, I may even discover, upon my return, that a challenging concept has suddenly slid into focus.

When I read this passage for the first time, I was awestruck, but I also believed I understood it completely. Green as I was, I figured I followed its elucidation of the work of freedom, the intellectual effort required to define and then pursue one’s desires (Gender is not my boundary!) as, if not distinct from social mores and pressures, then at least plastic enough to be played with. (I also perceived within it the kernel of transsexual privilege, which is that we get to have sex with everyone we want to because we are more beautiful and special than normal people, but that’s besides today’s point.) Over the years, my body has grown into this knowledge: I grasp the work of this kind of freedom. I am doing it all the time.

But in thinking that I understood this passage completely, I was mistaken, as I learned when I returned to it recently and sensed something new there. For a long time now, I’ve trusted in desire as a route to freedom; or trusted that freedom can be found in the honest embrace of desire. This is because I owe my desire everything. When I was young, it brought me to gay people, who eventually brought me to my current political commitments, which are broader than gayness, and include the commitments of those coalitions of which I’m not a member. Desire need not always be fulfilled—in fact, I think it oughtn’t be—but it should always be acknowledged, if not explored.

Gender is not my boundary. In my first reading of this line, I understood it as an imperative of sorts: If there is a boundary, it must be crossed—and thus, annihilated. Very genderqueer, as the enbies of my generation called ourselves. With this perspective, connection happens in the wake of destruction: like vampires, in making more of those like ourselves, we eliminate those who are not. But what if, instead of destroying boundaries, you brought them along with you to that island?

At an event in London a few weeks ago, I had a wonderful conversation about my book, leathersex, and dyke drama with Christie Costello. She asked me to define leather, and I did my best before putting the question back to her. I won’t paraphrase her answer, but were I to centrifuge it, the juice would gather round the word excess. Excess of gender, excess of sex, excess of feeling and of affect.

I think of Christie’s excess when I think of my new reading of A Secret Side of Lesbian Sexuality. Califia’s hot male masochist is my straight person, or my gay man, and these are not exceptions to my being a dyke, but rather included by it, subsumed by it. I connect more with highly-gendered people than people with whom I, ostensibly, share genders. Which in the context of this reading means, to me, that I do not bring people unlike me to the island, but rather that have found new ways to experience our likeness. Our connection by way of extremity is our similarity.

Who would be on my island? Total tops and absolute bottoms of a variety of genders and sexualities. I don’t switch in scene, but between them, occupying alternately strict realities that remain, like gelatin molds, soft yet fast. For this reason, I can identify with straight people, even those who don’t know what topping and bottoming is, over gay people who don’t fuck that way, or who are switchy or vers, or otherwise less rigid in what it is they do. This diversity of connection needn’t be a hierarchy of values; there is no right way, just the way that I fuck. That is desire. This is the kind of sex I like—sex that tests physical limits within a context of polarized roles. (NB: “queer” and “bi” and concepts like those work just fine for lots of people, by the way!)

My connections with highly-gendered people, and with people whose sexual sensibilities are, like mine, structured, controlled, formalized, rigid, inflexible, and courtly, overlap, extending even to straight people (and always has, I suppose). Benighted straight people! Straight women who are unwilling to give up the hidden power of heterosexuality and straight men whose sense of straightness is unshakeable, or is different from the conventional understanding of straightness (trade as straight, a queered heterosexuality that is, nevertheless, straight)—I love that shit. I also hate it. But I do love it. At any rate, it’s complicated.

There was a popular meme, for a minute there, that non-binary people were sharing that said something to the effect of If you’re attracted to me, you’re gay. Which, if that’s your experience of yourself, sure, fine. But I’m much more interested in the challenges of maintaining what are, for most of us, deeply held understandings of our own genders and sexualities when they are fundamentally incompatible with those with whom we vibe and fuck. How can straight people and gay people have sex? It happens all the time! How can dykes fuck fags? Literally every day. How can one be a monogamous sex worker? Easily! How can your identity not invalidate mine when our bodies push against each other? I don’t know, but it can!

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

November 10, 2022

DAVID: Members only

Photo of me :) by Tamar Shlaim

Photo of me :) by Tamar ShlaimThe working-class Glaswegian families of Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain abandon each other with miraculous ease: in the slums and SROs of Thatcherite Scotland, sisters betray brothers, fathers belt daughters, husbands deceive wives. Everyone is drunk or high or dissociated, and all are prone to random violence, beatings and sexual violence sometimes doled out with a mourning as disconcerting as glee. They drink and despair and self-destruct (sometimes metaphorically, sometimes not).

Dramatic as Shuggie is, for the first hundred or so pages, I thought it had been overhyped. My friend, Liz, who has great taste, raved about the 2020 Booker winner. It was well-paced -and constructed, I reckoned, and certainly entertaining—in the sense that it held my attention—but stylistically, I found it somewhat bland. Good? Yes. Excellent? I wasn’t convinced.

October 30, 2022

David Davis

When it comes to the humane treatment and conservation of other species (once-discrete concepts that seem to degrade every time we get another one of those U.N. reports), the name of the game is similarity: if we can convince the skeptical that non-human animals are just like us, our case for their mercy grows that much stronger.

By this standard, Sabrina Imbler’s1 How Far The Light Reaches: A Life in Ten Sea Creatures, is a great success. Over the course of this book of essays, they transpose the human body against those of various marine creatures—their grandmother and the Chinese sturgeon, sexual predators and carnivorous sand worms—to reveal the linkage between our wars and their migration, our family lives and their ecosystems, our industry and their disappearance. We (The West?) see the world as an entropic hinterland to be conquered and controlled. With their meticulous prose, whose discipline can’t conceal the enthusiasm of a true lover, Imbler disproves and rebukes the paradigm, leaving, if not a replacement, then room for something else.

This space is where transcendence happens. In “We Swarm,” their essay about Jacob Riis Beach and salp, the blobby marine invertebrate better known as the sea grape, they write about how it feels to experience our own permeability:

The poet Ross Gay asks if joining together all our sorrows—all our dead relatives and broken relationships, all the moments that make life seem impossible—if joining all these big and little griefs together, if that constitutes joy. As I watched the other beachgoers floating amongst the [salp], all of us strangers until this strange, shared moment, I imagined my body chained to their bodies. My sorrows to their sorrows. My survival to their survival.

Light has many moments of beauty, and many more of passion—Imbler’s fascination with the deep’s inner workings is endearing and contagious—but what’s really interesting about it is that Imbler is so good at this showcasing of similarity that they manage to cancel it out. Deposited into the same wading pool as feral goldfish, dancing yeti crabs, and necrotic blue whales, we are given the opportunity to espy resemblance we would not have otherwise noticed. But we are also given the opportunity to see difference up close, to appreciate its magnitude in a way our imaginations could never have conjured. Connection happens, but awe remains.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here. Also, I’ve had some interviews over the past few weeks. I’ll be in London next week, so find me at Foyles and elsewhere if you want to get a book and say hi.

1In case disclosure is warranted, Sabrina—friend of the newsletter—is a friend and a person that I like! And I think they’re a fabulous writer!

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 56 followers