Davey Davis's Blog, page 18

October 23, 2022

David Davis

It’s distasteful to admit that breaking the taboo did something for me back then, when I was still ignorant of the problems that being gay can cause. But when I first started dating L, I quickly discovered that more thrilling than holding her hand in public, appalling the religious, or feeling superior to heterosexuals was being able to say the words my girlfriend.

The pleasure this elicited came from someplace old, older than the adolescent urge to shock or infuriate. Saying my girlfriend produced the satisfaction of a child declaring their age, right down to the month, for the benefit of an inquiring adult (“Seven and three-quarters!”). I was not one of those little girls who wanted to get married; the phantom I was supposed to have been would likely have spoken of her future husband the way I say my girlfriend today, which remains: bashful, arch, incredulous, smug.

Venturing into a new kind of homosexuality is fun, especially when you can do it with your friends. Last night, I went with two other t boys to one of those grimy gay bars where you can drink cheaply, cruise in the dark, and sometimes get robbed. We stood around in a basement more sewer than grotto gossiping with each other and chatting with wasted guys, barely making it home in time for dawn.

In my experience of transness, public life is a paranoid arithmetic: how clocky am I alone? How clocky am I with Jade (less clocky as trans, it turns out, but whether I’ll read as a man or a butch woman is 50/50)? How clocky am I with my trans friends, all of us comprising a spectrum of passability that bloats like yeast, then implodes like a star, recombinant as DNA and inverted as we are, with every lightshift, jacket removal, gesture? Who knows.

At some point in the night, a tall white man approached us, too drunk to stand up straight. I’ve been married for forty years, he announced, and I just realized I’m bisexual.

Female-socialized as the three of us supposedly are, we smiled and cooed. That’s nice, I simpered. Congratulations, S lisped.

But the man was despairing, looking back over the lost years, hand to his forehead, high above mine. I’m bisexual, he soldiered on, and I need support!

The three of us shifted our eyes. You should drink some water, babe, I said. J, always effortlessly masculine, tapped the man’s shoulder with an open hand.

The man stumbled off, having been gently made aware that we weren’t offering what he was looking for. My hilarity—how bisexual can you be if you zeroed in on us, sis?—was a soft landing for my bitterness. My conscience said: Everyone deserves love and support, and the closet is a brutal shame. But my life was its rejoinder.

It’s raining today. Out late, up late. Instead of doing what needs to be done, I did nothing, until I went out for the ingredients for tonight’s dinner with Jade and a few friends. On Manhattan and Greenpoint, I remembered that I needed to supplement the pair of beautiful ceramic dishes a dear friend made for me, unless I wanted to serve my guests from pots and colanders. I got three bowls—two matching white, one angular and lined in blue—at the 99¢ Discount.

Groceries and bowls in hand, I sat outside a cafe near my apartment with a book (Zain Khalid’s remarkable Brother Alive) to wait for Jade. She arrived flecked in rain, like perfect fruit.

I got bowls! I pronounced.

Jade laughed. In her tote were a pair of beautiful ceramic dishes, because she knew I needed them. Then she was off to her tattoo appointment, fruit stung for beauty’s sake.

I’ve noticed the small and intentional reclamation of lover, that I’ve been predicting for a few years, has started taking place. I love it—love the word lover, and how gay people use it. I use it occasionally myself, and suppose that if it really does have a moment, even just among a wedge of New York-adjacent dykes, that I’ll use it even more. But while it feels good to say—a hearkening back to beloved gay people I’ll never know—it’s not my girlfriend. It can’t be.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

October 20, 2022

DAVID: Members only

Now that GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY has gone up to the big advice column in the sky (though BG and I may have a few tricks up our sleeves yet…), I’ve started thinking about how I’m going to do this subscriber-only content thing on my own.

October 13, 2022

GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY: Farewell

GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY is coming to a close. No regrets here—we’ve had a great run.

Two years into the mutual aid fundraiser that my anonymous gay therapist friend and I made at the beginning of the pandemic, our subscribers have sent over $30k to the orgs, projects, and people listed below. Bad Gay and I hope you’ll continue supporting them to the extent that you can. As for our gratitude, there are no words, other than that I feel very lucky to know BG’s true identity (and home address). Best of luck to you all, but they still have to give me advice when I’ve done something stupid.

Before I share BG’s parting message, a little housekeeping.

All subscriber funds through the end of the month will be sent to Food Not Bombs. After this post goes live, they’re getting the roughly $2,680 that’s currently in the bank. Anything that trickles in between now and October 31st will be sent there as well.

As of November 1, EYE will be keeping subscriber funds to pay my student loans (Dark Brandon or not, I’m still pretty deep in the red). You are welcome to unsubscribe! In fact, I encourage it! Send that $5 to someone who really needs it, or buy yourself a nice PSL with all the fixings. DAVID will remain free, though I’ll never turn a jaundiced eye on your financial support. I may even occasionally reward subscribers with exclusive content. In fact, I almost certainly will.

GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY will continue to be paywalled, though I’ll probably unlock posts here and there. You can always subscribe to get full access to the archive, which will be available in perpetuity, or at least as long as DAVID exists.

And now, your farewell message from my dear BG. It’s been an honor to have been assumed to be you for all this time! (BG is not me. I am not BG. Not all gay people are the same. I don’t give advice, usually.)

Dearest readers and advice-seekers,

In the depths of a strange time for the world, my dear friend David and I concocted GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY to connect to each other and to all of you, to have a few laughs, and to put money directly into the hands of organizations and causes that mean a lot to us. We are extremely proud of the $30,578 we were able to raise over the past two years.

We used David's platform to develop a very particular bit of fun—advice tinged with truth-telling, warm disdain for queer antics, humor, and genuine calls for all of us to see ourselves a bit better so we can do a bit better. Bad Gay, despite my credentials, was only my clinical voice in part. There is a therapeutic lens underneath the glibness in the columns, but Bad Gay has David's voice in it, too. We spend a lot of time dissecting the communities we love, the people we love (both parasocially and actual-socially), and the patterns of gleefully ill-behaved queerness that we, I think, both believe is our inalienable right: to exist and be messy and learn.

Thank you to the advice-seekers, the readers, and the subscribers who helped us get funds to the people that need them, and most especially to David. I would be remiss, as I wrap up, not to remind all of you to dig in and ask yourselves, whenever possible, "What is my commitment to suffering?"

Have fun, keep fucking up, and we'll see you around.

Bad Gay

GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY MUTUAL AID RECIPIENTS

Free Ashley Diamond (As of this summer, she is now free!)

Venus Cuffs’ ongoing NY-based fundraiser

Minnesota Prison Writing Workshop

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

October 6, 2022

David Davis

Stills are from “The Rape of Christ,” one of the scenes deleted from Ken Russell’s “The Devils” (1971) for obscenity

Stills are from “The Rape of Christ,” one of the scenes deleted from Ken Russell’s “The Devils” (1971) for obscenityIn “A Secret Side of Lesbian Sexuality,” Patrick Califia makes passing mention of bottoms outnumbering tops in the San Francisco leatherdyke scene of the late 1970s. Califia wasn’t the first to notice the queer “top shortage” we’ve heard so much about. But I once read, somewhere, that at the dawn of leather—or maybe even before “leather,” what we call the gay sadomasochist subcultures born of American postwar veteran and biker clubs—this phenomenon was reversed. A half-century before Califia was on the scene, according to my source (Maybe it was Mark Thompson? Maybe you can track it down?), it was the bottoms who were in short supply, forcing tops to compete for their flesh and attention.

Though in the past I’ve been forced to do extra legwork in order to weed out the fakes and the freaks, I’m a good masochist who’s lived in big cities for almost 15 years, which means I have both the ability and the privilege to avoid said top shortage. But of course I’ve noticed, or thought I’ve noticed, an imbalance in the roles that anchor our erotic lives. For as long as I’ve been in leather, my sadist and top friends have been in high demand, the inverse of pass-around Pattys, servicing a bevy of needy pincushions and thirsty holes. This imbalance appears—or is at least bitched about—in the broader queer culture, too, brought to more mainstream attention in gay thinkpieces over the past five years, though these seemed to have peaked not long before the pandemic began.

Has a fad discourse receded back into the ether where it belongs, or has something real shifted? Recently, my friends and I have been going through a gangbang phase, and in the process I’ve realized that there are more tops and (true) switches than strict bottoms in my life. For instance, it’s been no trouble staffing our gangbangs, where tops will outnumber the bottom by at least 5 to 1. On the other hand, finding bottoms to take all our cocks and boots is, if not difficult, a disproportionately taller order than finding said cocks and boots. By the logic of the so-called top shortage, it should be the other way around.

What gives? I have my theories. For all the blood and guts-rearrangement, bottoming isn’t necessarily harder or riskier than topping, but when you reach a certain level of play, where experience takes precedence over a willingness to try new things, a seasoned bottom is as much of a luxury as an expert top (an open-minded novice can only bring you so far—getting good at being used takes a lot of practice!). Perhaps inflation has gotten us here, too, rendering the bottom’s skill set more dear than ever and skewing its value in relation to the top’s, like the dollar superseding the pound.

Then there’s the makeup of our gangbangs, which this summer have happened among friends and friends-of-friends. We don’t have a greater responsibility to our bottom’s welfare because we know their name, but there is a difference, I think. Among strangers, respect is understood; among friends, love. We may sleep with our bottom after the gangbang is done. We will certainly be there for them the morning after, and the morning after that. Which is to say that in a gangbang of friends and lovers, rather than of strangers, where experience and intensity and intimacy converge, the needs of the bottom are greater than ever. If the bottom requires a satisfaction that a single top can’t provide, they will also require commensurate protection from themselves, from the ravages of their own desires.

“It takes a village,” I said as I lifted our bottom up onto the bed, their arms bound behind their back with pink rope. We laughed. Another friend helped me support our bottom’s weight, while a third held their legs apart so a femme in black vinyl could push herself inside.

Suppose there was, for a time, a top shortage. Suppose that it’s now gone, for some reason. Because bottoms have become more brave and voracious, perhaps. Or because tops crave a challenge for their caretaking skills, more developed since the country has undergone a mass-disabling event. Or because all of us have greater rage to excise, and a deeper need for connection.

Even if this reversal, from a plurality of bottoms to a dearth of them, is real, all of this is anecdotal and personal and highly speculative; if the top shortage is indeed now a bottom shortage, it may well be a phenomenon limited to my individual sexual ecosystem, which is admittedly bigger than most. But so much has changed over the past few years. Is it so unreasonable to think that this change brought about a significant, even seismic, shift in our erotic lives? Where once the role of the victim was more popular, now the role of the predator is. Perhaps it has become more difficult to need, or more appealing to control. Perhaps both, or neither, or something else.

In a gangbang, the bottom receives more attention, stimulation, focus, and (after)care than their tops do. This isn’t to say that their top(s) do not also receive these things, but the one who gets fucked, who struggles, bleeds, weeps, and withstands, will need first aid, comfort, tenderness, and relief that the top will not, in ways that the top will not. What has changed, over the past few years, to have altered the resonance of these experiences?

For the summer’s first gangbang, I shared my girlfriend with my friends, negotiating, managing, and running her turnout for an intimate group leatherdykes. It felt like being an auteur directing my favorite actress—a star is born! I felt very close to Jade, and very close to my friends, all of us together, a family, focused on our bottom—our main attraction, our doll, our charge. Afterward, we ordered french fries and ate them in a big hotel bed, lingerie traded in for oversize t-shirts, talking about this and that until we fell asleep.

I have not always liked sex, but what I’ve always appreciated about doing it in a group is the redistribution of responsibility. Less pressure, without diminishing returns. In some circumstances it can feel communist, utopic. With a gangbang in particular, everyone other than the bottom can tap in and out as they like. Sometimes you are active (co-starring as fist-fucker, or playing a supporting role with tongue or toy), and sometimes you sit, watching actively as a voyeur, or passively as you rest, maybe with an arm slung around someone’s shoulder (this is a time when I feel so comradely, so fraternal). You step in and out as you’re needed, restoring yourself with a snack, a drink, some drugs, a piss.

Two dear friends have recently had their first child, and I haven’t spend as much time around an infant since my youngest sister was born when I was 18. Even with two adults (two-and-a-half with me, someone who is not as helpful and can’t breastfeed, but can hold, bottle feed, burp, and entertain), the work of a baby is very demanding; even with all of my years of caretaking—my whole life, with babies of many ages, and people of many needs—I marvel at the effort required to be someone else’s universe.

I have never wanted children of my own, but I adore them, especially infants. After I met my friends’ baby, I told my therapist about how good it felt to care for someone whose requirements, while extreme, can be completely and entirely met. I love that their need is not in vain with me. Unable yet to question whether they will get what they want, I can ensure, as long as I am with them, that they won’t have to.

If America’s incest fantasy could be peeled apart, like a banana, the fruit inside would be thick, sweet, and less convincingly phallic than its exterior might suggest. My theory is that the substance of this edge fantasy is an intimacy that can be taken for granted. Imagine.

The urge to break the incest taboo suggests a powerful craving, one highly gendered but ultimately plastic, for sexual and filial certainty that can never be rent asunder, no matter the risks—such as being caught, whether by another family member, or your friends at school, or the authorities. To fantasize about incest suggests the fulfillment not just of desires, but of needs. I want this so badly that I need it. And it’s right here, provided for me by someone wise enough to know, and strong enough to give. Maybe it’s punishment. Maybe it’s nurturing. Maybe it’s an orgasm.

As a lover, I strive to take taboo desires on their own terms, doing my best not to assume that they are facades for something more real. But as a writer, I’m curious about the affects smuggled inside them, hidden below the surface like a cooking pot’s nascent simmer. I suspect the incest taboo contains an aggression that’s at turns righteous and indignant. In scene, it feels to me like a furious demand for authenticity. By that, I mean: the great harm of child abuse (which is really what we’re talking about when we talk about the incest fantasy) is the betrayal. The second great harm is the denial of the first, the universal gaslighting by family, church, TV, school, doctor, policeman, and culture. To embrace the incest fantasy affirms that you are not crazy (or maybe you are, and who gives a shit?), that harm really was perpetrated by those entrusted with your care and growth, and that while your response to it was not of an uncomplicated and uniform rejection, that that’s okay, too.

You don’t have to be a survivor of literal CSA to see the appeal in that, I don’t think.

When I look around me at the reading, the rave, the sex party, I see gay people of all backgrounds, the vast majority of whom have survived some kind of schism from their natal family. Even those who retain those connections completely do so under duress. But this is not unique to gay people, though in a way it’s reassuring to pretend that it is. As much as “chosen family” has arisen to describe a specific solution to a certain kind of gay abjection, people are exiled from their natal families all the time, and for all kinds of reasons. The nuclear family is created by the state, only to be broken by it—by foster care, prisons, and mental facilities; by the institutions of marriage and divorce; by wage labor, debt, and poverty; by gendered, racialized, and ableist divisions of labor and love.

Is it any wonder that incest has an appeal for some of us? We were promised a family, and a home, an unconditional love that can never be broken, no matter what we do or don’t do. We were promised that harm, should there be any, would always come from without. We were promised that there was recourse for injustice and failure. We were promised, if not safety, then community.

We were also promised that the closest intimacies happen in families; if it happens within the family it is, by definition, love, even if it hurts or is scary. If love does take place outside the family, it must be legitimized by the family’s legal reorganization, via marriage or adoption. One is bred to question if you can really have love outside of your birth family, which means that losing it means losing love, all of it. If you manage to overcome these terms—which constitute heteronormativity, among other things—and replace that love, is it any surprise that that love feels like the family you lost?

In times of fear and disaster, the bonds that don’t break are strengthened, or so they say. Jade and I started dating not long before March 2020, so we can also joke about COVID fast-tracking our romantic relationship. Where would we be, as a couple, without it, I wonder? Would we still be at this gangbang, with these people?

One of the linguistic patterns of gay hookup apps like Grindr, I’ve noticed, is the inclusion of the term body contact on a list of desired activities. Kissing, oral, rimming, body contact—as if the first three can be accomplished without the last. The language is both unappealingly clinical and yet endearing to me, functional in its straightforwardness, but almost too useful to be erotic, to my ears, anyway. And yet, as someone who has felt starved for touch for years now, I understand it. I use it myself.

I want to walk into the room where my friend is being fucked, take off my clothes, and fuck my friend, too. I want Jade to stroke my hair while someone gets pushed against the plate glass, their body flush with the skyline. I want to conspire with another top about swapping girlfriends, radiating laughter. I have been telling men whose names I don’t know that I love them. I take the person that I love the most and I give her away. I can afford to be generous; it feels good to have someone, and it feels good to share the having.

Incest, as the state understands it, was never about child abuse. The taboo is somehow big enough to contain sodomy, gender nonconformity, non-whiteness, the reasons for which we’re accused of grooming everyone around us, yet it’s not big enough to stop children from being harmed, particularly by their legal guardians, whether those are natal family or the state. Under suspicion of love, what you have to offer is criminalized, explicitly or tacitly.

This summer’s gangbangs weren’t my idea, but after COVID, which for me meant years without other lovers and months without my girlfriend, I was ravenous. Then monkeypox happened. Still reeling from one plague, here was another. I could feel the deprivation in my body. Could others too? I’ve been fucking a lot, unable to decide if it’s good or bad. But it feels good, so who cares? I know how close I am to losing it again.

Of those who have survived AIDS, COVID, and MPX, many have been permanently affected, not just directly in their bodies, but by extension: by stress, lost jobs, worsening work conditions and healthcare, the constriction of social services, skyrocketing rent and the shrinking dollar. The nuclear family, our supposed safety net, is further exposed for what it is, the bones splitting the offal from below. It was never going to work, for us, anyway. Is that why desire for incest in our porn has skyrocketed (I promise I’m not just revealing my personal curation)? Why it continues to shock, despite featuring in our most popular mainstream TV shows and films?

As the emotional valence of the family changes, so must the anti-family. Our erotic lives are never untouched. Is that why the top shortage went away? Is that why?

What does a top (or bottom) shortage tell us about the world? I don’t know. I don’t want you to think of this is a diagnosis, much less an attempt at an explanation. In times of change, I leave that to the experts.

I’ll leave you with this: instead of “chosen family”—an expression that I’ve come to loathe—I prefer the unwieldy but much more beautiful “consensual sentient state of relationship,” as Rena Davis-Phoenix puts it in Michelle Handelman’s BloodSisters. But what does that accomplish, I wonder, that gangbang doesn’t, and so much more succinctly, too?

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, DAVID’s advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

September 25, 2022

David Davis

In grad school1, my advisor was a mediocre homophobe who was occasionally good for solid writing advice. This was a decade ago. At 24, I was still an unthinking grinder, pestle to my own empty mortar, so it verged on the revelatory to hear a real writer—with books and a teaching job and everything—insist that sometimes the best thing you can do for your manuscript is sit at a sunny window and daydream.

Her enduring mid-ness aside, I’ve come to think my advisor was onto something. Over the years, I’ve discovered that the window is not just indispensable, but undeniable. The body needs time and space to process. When I force the painstaking, backbreaking effort needed to go sit by the window, I’m often rewarded with a passage that wouldn’t come or a plot hole finding its bite. Sometimes I can’t connect the window to any writing accomplishment, but its proximity makes me feel better. Unfortunately, restoration counts as one of its benefits, too.

My advisor had a lot of ideas, some of them about the legitimacy of trans people, but she failed to offer any suggestions for actually getting to the window. I had to figure that out myself. I believe in hard work, if only by virtue of its difficulty, which is a belief that leaves little room for reverie. When I feel myself resisting the window, a state of mind more daunting than eight hours in front of my laptop, I try to make it more palatable with a reframe: if doing nothing in front of a window is hard, then it counts as work, right? (And shouldn’t hard work be its own redundancy?).

It helps to enlist other writers, ones I actually respect, to strengthen my case for the window. “So much of making art is the time spent not making art,” Raven Leilani told BOMB Magazine a few years ago. Craft is earned with effort, but isn’t guaranteed, not least because the conditions of that effort are never a given. “To make anything,” Leilani went on, “you need the means and time, and you need to be intact, and that is frustrated by the racist, sexist, and capitalist forces that all contribute to your erasure. So to be able to make art is a privilege and a refusal of this erasure.” The window, then, is not just a gift, but a responsibility and a provocation.

This understanding of craft, then, requires work—a nonnegotiable for anyone who must draw a wage to survive—while also requiring its subversion. Craft becomes the workday’s byproduct, a silver lining wrung from the laborer along with the value that their labor produces. It’s also a powerful antidote to the contemporary push to literally separate art from the artist, an anti-worker project if I’ve ever heard one. Art, as Gretchen Felker-Martin wrote last year in a piece about moral panic as back door to censorship, is the culmination of “both labor and experience,” a stance with which any self-interested worker, artist or not, should wholeheartedly agree. (The window watches me, a taunting cyclops.)

Though what we do is usually described as intellectual or even white-collar, as writers we cannot fail to conceive of what we do as labor, even those moments between, when one sits by the window, chin cradled in palm. My soft-handed job is preferable to any I’ve ever had, but that doesn’t mean it’s not work, an uncomplicated position that seems—with the past week’s “Are baristas proletarians?” coursing through Twitter like Taco Bell through a Millennial’s colon—to nevertheless be controversial.

Divisive, anti-worker propaganda aside, sure, the notion that we do as writers—artístes—is not actually work can be so very tempting. Such a possibility frees us from having to think about the ways in which our embodiment complicates our politics, our experience, and our identity, and thus our art. “The body can seem like a problem, but it can also bring us together,” counters T Fleischmann. With their book, Time is the thing a body moves through, Fleischmann seeks to “push against some forms of knowledge” by working/engaging with visual artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres without having something “definitive” to say about him. Gesturing, flirting, suggesting, winking, nodding, cruising, and fantasizing, Fleischmann wants to meet the body on its own terms, resisting certainty as both form and praxis. (What does the window know that it can teach me?)

And yet work, as a straightforward, quantifiable exchange—x hours in, y words (dollars/clicks/books) out—remains seductive. “The form demands discipline, and through that discipline, urgency,” says Leilani. In that urgency there is purpose and, supposedly, a reward; a pot of gold tantalizes at the end of the rainbow. Though I’m fundamentally repulsed by his prioritizing of style and structure over “the great idea” (which he called “hogwash”), my dear Nabokov’s dedication to component can be read as another kind of subversion. “Caress the details, the divine details!” he urged, which dictum we can reappropriate for our anti-work perspective: what is work if not effort with a capitalist agenda, rendering pleasure incidental? Indeed, in his rebuke of Nabokov’s whole deal, Updike invokes the writer’s essential dialectical tension: we dash our inherent “will to manipulate” (hi, liar!) against the “banal, heavily actual subject.” How romantic. Like an open window on an autumn afternoon, chilly Brooklyn below inching past on its Saturday errands.

I prefer to view my work as a writer as being in service of my political commitments and, failing that, my own pleasure. It’s a lot of pressure. Reducing art to work can be freeing, if not liberating. It’s something that working people do, this craft of mine. Decent, salt-of-the-earth, but moral only insofar as it’s constitutionally bracing, like a loaf of home-baked bread. Or a window that, I just noticed, needs Windexing. This reduction plays into the pleasure I take in artists who conceive of themselves as tradespeople, or even better, as workmen, as Jack Nicholson calls himself in a 1986 interview with Rolling Stone. “My first acting teacher said all art is one thing—a stimulating point of departure. That’s it. And if you can do that in a piece, you’ve fulfilled your cultural, sociological obligation as a workman.” Workman. Ah. Bracing, honest. Puts hair on your chest.

Of course, this pleasure is a fetish of sorts, relying on fantasies of what work is, does, and feels like. In opposition to an increasingly always-on office environment, or scraping together a living from the gig economy, or clinging to what remains of the twentieth-century’s union gains, the notion of clocking in and out at a satisfying, decently compensated 40-hour-per-week job (don’t forget the pension!) is such a fantastic fantasy that one might forget altogether that even if it were attainable to you (it almost certainly isn’t), that attainability relies on the exploitation of workers of which you can only imagine. (Do those workers, either alienated within the imperial core or conscripted into its replication outside its borders, have a window?)

Now it’s dark, and my window has lost some of its potency, though if I crane my head, I can see the ghostly Manhattan skyline through the trees and condos. In writing about the window, I’ve failed it. My book is still not done.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, DAVID’s advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

1A phrase I only rarely let loose from its rubious attic chains. Please don’t ask me about it.

September 17, 2022

Phyllis Christopher's "Dark Room"

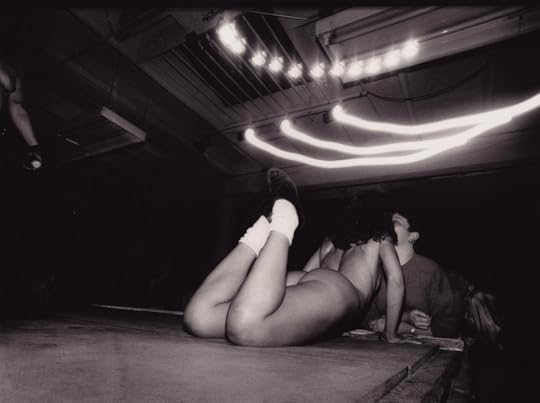

"Dancers", Club Ecstasy, San Francisco, CA, 1991

"Dancers", Club Ecstasy, San Francisco, CA, 1991If you watch porn, you may have encountered camerawork that’s almost surgical in its focus, trained on specific parts of performers’ genitals with a fixity that might make you feel like an OB/GYN (or urologist, or proctologist. Whatever). With this kind of closeup, you’re telescoped almost inside your subject, to the extent that someone glancing over your shoulder may not even recognize the mucus membrane that fills your screen.

Whether this perspective is the result of a creative decision or practical circumstance—like low production value, for example—there’s nothing wrong with getting up close and personal with pussy. Ethically and artistically speaking, it’s no more objectionable to me than fixating on a face or a foot, which is to say, not at all. But since I’m not a genital fetishist for whom hole successfully synecdochizes the whole, such a limited visual range just doesn’t do it for me. My loss, I suppose.

Unfortunately, we’re rarely in the habit of judging erotic art by whether we find it arousing, unless we’re looking at it critically as art, in which case its potential to arouse will probably be grounds for artistic dismissal. In art that is regarded as non-pornographic, zooming in on a single body part might read as familiar, lingering, or personal. For art that’s considered pornographic, however, such good faith is rarely extended. A certain kind of feminist might echo a certain kind of anti-feminist in arguing that, in a porno, this closeup is objectifying because it replaces a person with one of their components. (Have I reinforced this tendency by describing this kind of camerawork as surgical, thereby associating it with our meatiness under the doctor’s knife?)

We don’t make such mistakes here, of course. What am I but a sum of my parts?

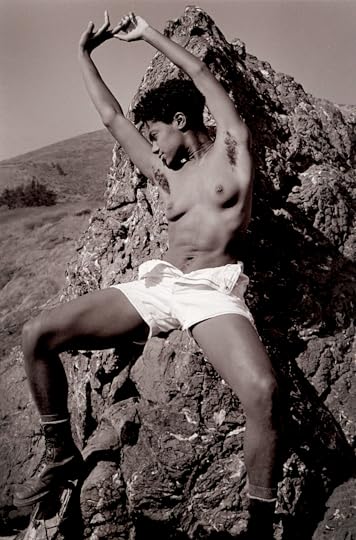

On Our Backs Pin-Up, Marin, CA, 1991

On Our Backs Pin-Up, Marin, CA, 1991The distinction between “good” and “bad” closeups came to mind while I paged through Phyllis Christopher’s Dark Room: San Francisco Sex and Protest, 1988-2003, a sumptuous and stunning archive of lesbian and queer life1. In “Tongues, San Francisco, 2000,” an open mouth engulfs another, the blunt smudge of tongues contrasted against the gleam of teeth, metal, and lip. Something, perhaps a human figure, is reflected in the ball of a piercing, bright against the black of the throat. Though we know what we’re looking at, this image is difficult enough to parse that all that we do know about it is that it’s (homo)sexual. Lascivious. Pornographic. Have the dykes who serve as our subjects here been dehumanized by this perspective?

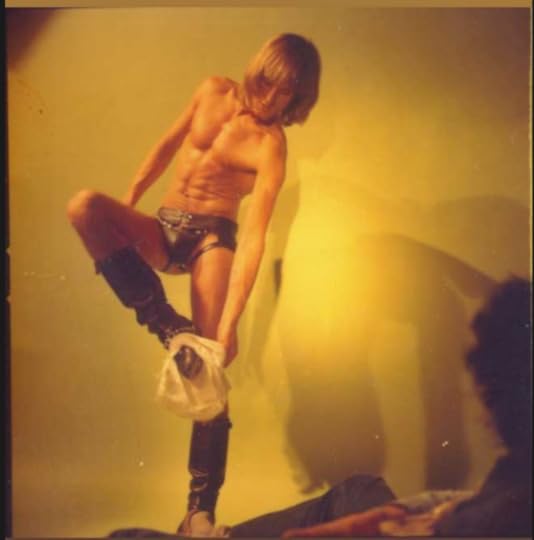

Dancer, Club Ecstasy, San Francisco, CA, 1991

Dancer, Club Ecstasy, San Francisco, CA, 1991Re-situated in a context where the pornographic is not a dead-end, the closeup takes on a new emotional valence. Very little in Dark Room would escape classification as dirty, seedy, blue, and yet these images from our gay past feel like home to a certain kind of homo, whether or not you’ve ever lived in the city by the Bay. From street brawls with pigs to spreads for On Our Backs, Dark Room zooms all the way in on taboo with butch on butch fucking, titty gloryholes, bloody live performances, go-go girls and boys, whips and chains, butch/femme “roleplay,” as it was once known, and strippers of all kinds, reveling in an intimacy that the straight lens would likely seek to flatten.

Marcus, San Francisco, CA, 2001

Marcus, San Francisco, CA, 2001Though its subjects are often genital—pierced nipples, pissing pussies, winking vulvas—Dark Room’s closeups also feature genitalia that only dykes would recognize, our means and methods of fucking that hide in plain sight: hankies, mouths, fists (“Do Lesbians Cruise Hands?” asks a cartoon in “Cartoonist Kris Kovich, San Francisco, CA, 1992”).

That’s the other thing about the zoom: allowing for a level of anonymity, it becomes a queer tactic of safety. “I think we were developing a lesbian visual language,” says Christopher in an interview with Shar Rednour at the end of Dark Room. “Maybe it didn’t mean so much to other women, like they thought it was just fashion. But to me it was very important because it was the way we identified each other in crowds and in smaller cities.” Having found each other, of course, there is opportunity to zoom out again. The lens widens, restoring the whole from which the hole emerges.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, DAVID’s advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

1You can see more images from the book here.

September 6, 2022

David Davis

In my early twenties I was denied top surgery because I was too feminine. It was explained to me by medical professionals with jack o’lanterns for hearts that the way I looked and lived my life meant it was unlikely that medical transition was what I actually wanted, which fundamental desire was buried deep in the very quick of everything that’s wrong with me, like a beetle in dung. My already-embattled relationship with femininity grew a new ring: usually too butch by default, I was now too faggy. Hello Kitty was definitely involved.

Some genders are best understood in terms of volume. For some, excessive does more work than any single label can, while neatly accounting for the consequences of gender variance without forcing you into essentialisms or explanations. There is a reason why I identify with femmes so deeply, despite our playful pretense of being perfect opposites.

Like when I’m out of town, as I am right now, Jade complains that she’s been weakened by years of not carrying her own bags, which normally I don’t let her do; now that I’m gone, she’s helpless! This is an inside joke that butch/femme type of gay people love to tell ourselves: we both know that Jade is actually capable of carrying her own bags and that I wouldn’t actually die of embarrassment if she did, but to pretend otherwise complements our genders, lifelong sensations comprised not just of pinpricks of euphoria (as everyone insists on calling it these days), but insecurities in need of regular reassurance from someone who understands without relating too directly.

One of gender hierarchy’s tricks is making us believe that intimacy only happens by way of similarity (which myth sits paradoxically astride the idea that it only happens by way of heterosexual copulation, itself dependent on difference). This is a natural conclusion of allowing the notion of balance to limit your desire. But if both of you are too much, then your genders can never cancel each other out.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, DAVID’s advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

August 25, 2022

David Davis

Smothering though our bewitchment by “generation,” as an organizing principle, may be, I think it’s safe to say that The Brave Little Toaster—Toy Story’s darksided 1987 ur-text—is a millennial touchstone. Following the adventures of a group of household appliances searching for their “Master,” the young boy they live to serve, our inanimate heroes are animated by creamy colors, cheerful singalongs, and the ever-present threat of obsolescence, physical destruction, and ultimately psychic death. Such is the fate of the dubiously-gendered sentient consumer good.

Toaster's first kill happens just a few minutes into the movie. Taunted by a malevolent air conditioning unit who claims that the little boy will never return to the vacation cabin where they all live, Toaster and its friends accuse Air Conditioner of jealousy (Master doesn’t play with HVAC, you see), triggering it until it overheats and explodes, leaving behind a smoking corpse wedged into the windowsill.

Voiced by the late, great Phil Hartman, the cruelly sarcastic Air Conditioner is obviously a caricature of Jack Nicholson. Sneering and leering like the Great Pumpkin of New Hollywood himself, Air Conditioner’s filtration design suggests Jack’s shining cupid’s bow, broadly and brightly dimpling and from which point gravity’s obligate rainbow drags his facial excess down into cinema’s original Jokerfied grin. From the raspy voice to the idiosyncratic cadence to the plasticine brow, there’s no missing the resemblance. But for me, Air Conditioner didn’t register as a cameo, as it were, because I didn’t recognize the source material. It would take years, both of caricatures like Hartman’s and the opportunity to see the original himself in other movies, for me to pick up on the homage.

When my parents were children, cinema legends like Peter Lorre (another film star lampooned by Hartman in Toaster, he as a bag-eyed light fixture), Katherine Hepburn, and Humphrey Bogart often turned up the cartoons they watched. I wonder how often my parents recognized them, and how often they were assumed to be a strange new character in a harem of scribbled freaks. Nicholson’s ambience took place before my awareness, while I was still in the early stages of sponging up the culture; I suppose that’s how ambience works. But eventually, Nicholson would come to be as recognizable to me as Jesus, Elvis, the president, etc., as I was reminded when Jade and I watched Easy Rider (1969) for the first time last week.

Nicholson’s role as the alcoholic lawyer who delivers the film’s keynote—“What you represent to them,” he informs his hippie comrades hours before his own brutal murder, “is freedom.”—got me. Earnest and boyish, he’s a pre-calcified Nicholson, who for all his remarkable versatility suffers from the constraints of caricature, as all greats must. When was the last time he was in something? I wondered. Now 85, he’s elderly enough that he no longer appears at Knicks games or in the tabloids along with Lindsay Lohan. One assumes he’s been made comfortable in a mansion, smoking stogies and reminiscing about a coffee shop called Poopie’s, up on the strip, the phlegm rich and murky in his agéd throat.

I love a genius. Every so often I develop a little romance with a new one, sacking the library for their books and piping in podcasts about their illustrious lives. In one interview, Jack humbly responded to a question about missed opportunity (he famously passed on The Godfather, among other classics) by quoting his own mother: “All comparisons are odious.”

But comparison is its own pleasure, and there’s much to be found in the long life of a great and productive artist. I’ll never be anything but a writer, but as artists I think we ought to study forms other than our own, which is why I care about the Method, or Italian Neo-Realism, or queer of color critique. Gone about a certain way, comparison erodes the difference upon which it relies. Caricature is undone, and yet ever ascends.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, DAVID’s advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

August 11, 2022

David Davis 39, part 3

Frankie and I met up at Metropolitan. For a few hours, we sat at a corner table on the back patio, smoking, drinking, and wiggling our fingers at trans people we recognized from the internet. After dishing about our jobs, our girlfriends, and Gretchen Felker-Martin’s banger episode on the Gender Reveal podcast our conversation landed on people who are stuck—those pitiable souls who can’t admit they’re queer or who won’t transition, and maybe never will.

Why do grownup transsexuals like Frankie and I have any interest in stuck people? Because we’ve been them ourselves, to varying degrees, and will never outrun the risk of becoming them again. Because, deep lez though we are, she and I know people like this, and as long as heterosexuality exists we always will. For as much sturm und drang there seems to be around community—what it means, what it does, who’s in, who’s out—the construct is nothing if not dynamic. Community is something you do, not something you have or are in. As such, stuck people meander in and out of our lives as friends, lovers, coworkers, acquaintances, nemeses. Are the stuck people here with us in the room right now? Often! Even if they do tend to have one foot out the door.

You can’t talk about closet-cases without talking about chasers, too. Many people, and not just the straight ones, are fond of accusing our biggest fans (as well as our fiercest enemies) of secretly being among our ranks, which is facile and stupid and transphobic, actually. But that doesn’t mean that cis fascination with us—of both the positive and negative tenors—can’t be located in their relationships with their own genders. As trans people, we are symbol and proof of the world’s unraveling, which sounds pretty dramatic until you’ve been on this side of things. In our realness, trans people expose systemic artifice so foundational that departing from it in thought or deed can literally drive you crazy. Confronting that is terrifying, especially if you’re cis, since in that case you actually have something to lose if the whole thing were to ever come tumbling down. This means, incidentally, that cis fascination with us is also about power. But when is gender not about that, too?

Are all chasers stuck? No, I don’t think so, though of course many of them are. If you’re trans, and particularly if you’re transsexual, then you’ve surely encountered someone who loves you because they can’t see you—only themself, or a version of themself that they wish existed. Or perhaps they see you so much they can’t see themself at all. However you slice it, you’re not having a person-to-person interaction with them, or only rarely. How can you, if not everyone in the room is a person?

Frankie and I can happily bitch about chasers at length, but for my money there’s a time and a place for them, as long as you know what you’re doing. It can be fun or sexy to be worshipped, especially when the reason for that worship is why the rest of the world reviles you. If everyone is going to be obsessed with us, at least the chaser variation comes with perks.

My advice for indulging chasers is this: think of your time with them as a vacation from being a person, rather than an exiling from humanity. Just don’t forget that vacations, by definition, are temporary.

In part one of this series about gendered social contagion, I said that I wanted to write about “the cis people who saw my transness” before I knew of it myself. The chaser can’t see anything but my transness; in this way, they’re indistinguishable from almost all other cis people.

Who was my first chaser? I asked myself. Not gay men on hookup apps. Not the cis femmes who talk about trans mascs as if we’re pets or men, but can’t find it in themselves to date anyone else. Not the dykes who asked me not to transition, but watched trans porn exclusively. Not the straight men with force fem fantasies that could only come to life in the dark. Not the straight women who felt I should be grateful to fuck them, and met any disinterest on my part with indignation and shock.

If we’re defining the chaser as someone who calls their obsession with your gender love, then my first chasers were probably my parents. Which is to say that the people most invested in making sure I wasn’t trans played a role in bringing it to pass.

In liberal terms, the rights of trans people are often framed along the lines of “expression.” It’s inhumane not to permit us to be authentic to ourselves, goes the logic; when given the opportunity to do so, we are bravely living our truths. However well-meant, the closet understood as facade positions us, a priori, as liars. As I wrote in another post, “If our genders are produced, that means that the concealment, deception, and revelation of deviant genders is also produced.”

I don’t think the closet metaphor goes far enough when understood in this way. For me, closeting was not like wearing a mask or a costume, allowing for at least some part of “the real me” into the daylight. It was like being dead. Gender organizes how we share information about ourselves—that is, it’s how we communicate. Our genders inform and shape how we are polite and rude, gentle and violent; how we convey want, need, desire, and interest. Like age, race, class—a whole mess of things—gender (like community) is something you do. Even agender people must interact with people with genders, in cultures and milieus organized around normative gender, and are beholden, on some level, to gendered interaction, particularly in how others understand them. Without your gender (or lack thereof), as you understand it, you are nothing. Maybe, like me, you’re spiritually dead. Maybe, like trans people without the luck and safety I’ve had, you’re literally dead.

So. Say your gender isn’t safe. Say your only alternative, for the moment, anyway, is death. The thing about chasers is that they, like transphobes, see dead people. As I walked home, thinking over my conversation with Frankie, I wondered what would have happened to me if the chasers had never found me, over and over again. They’re cogs in the system that produces deviant genders, sure. But they’re the bloodhounds that sniff us out, too. Maybe a better comparison would be one of those fish that live on the shark’s pearlescent underside, feeding with the focus only a parasite can offer.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

This week, Astra published my piece on Nitehawk’s Pride screening of BloodSisters: Leather, Dykes & Sadomasochism (1995), feat. my leather associate, Daemonumx, if you’d like to give it a read.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, DAVID’s advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

August 5, 2022

David Davis

Mom got up early to get C ready. After she left, C circled, trying to pick a fight with me. I sat at the kitchen table and waited for her. You can offer me a drink at Starbucks, brother, she would attempt, and I would offer it, and she would get overwhelmed, go to her room and wail, then come back and try again. Still, she has done very little screaming this visit. No door-slamming, no name-calling. Mom and I have remained calm, though I got short with C in the car this morning when she, to be contrary, insisted that our grandmother was not a grandmother.

I was driving C to Grammy’s because there was no one else to watch her, and Mom and I had work. I don’t like putting Grammy at risk of COVID, but she insisted, and Mom is exhausted. I’m exhausted, too. On the way there, we saw a truck that said SOCIALISM on the back window. You couldn’t see the part that said SUCKS until the truck was a half-block ahead of us. On Grammy’s street, I waved to two ancient white people before I realized both were wearing bright red MAGA hats.

Grammy was the same but frailer, hair now lapsing white. Your mother is incredible, she said. I tried to be polite; I was not supposed to have seen her again before she dies. C wanted me to leave, kept touching my wrist and looking at the car. Your legs are swollen, she said, shaming me in front of our grandmother, who hates my body. You look wonderful, Grammy said. I forgot that she has cancer again.

In the car, I cried. I think my tears are less salty now, but also more buoyant, rising up from my skin like the kind of nipples that are my favorite.

The ash is on the street, like dust, and in the plants, like big grains of salt. I wanted to call Mom and ask her to tell me I’m not a bad person, but I didn’t. The tears smeared my mineral-based sunblock (chemicals are dangerous). The fire is still going, but the air quality is better today. Grammy does not understand how contagion works and probably never will.

Find me on Twitter. Get my second novel, X, right here.

Subscribe to support GOOD ADVICE/BAD GAY, DAVID’s advice series from an anonymous gay therapist who’s not afraid to hurt your feelings with the truth. (Sample an unlocked post for a taste of what you’re missing.) 100% of funds go to support a rotating selection of mutual aid and reparations projects.

Want advice? Email badgayadvice@gmail.com for a free 3-month subscription.

DAVID is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 55 followers