Davey Davis's Blog, page 9

May 24, 2024

David Davis, part 7 ½

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, and Part 7.

Though I’ll soon be attending a local screening of Hellraiser (1987), the first film in the franchise based on Clive Barker’s The Hellbound Heart, the series is one I mostly enjoy in theory1. I’m squeamish in the cinema, and B-ish horror tends to disturb me far more than the higher-production stuff, retaining as it does the scrappy anti-authoritarianism that defines the best of the genre. Though I’ve seen Hellraiser before, there’s a strong chance I will still cover my eyes as Barker’s Cenobites, the S&M-inspired beings who transcend sensation and dimension, pursue the pleasures of eternal torture.

It will come as no surprise that the Cenobites were inspired by Barker’s visits to 1970s S&M clubs, which were aesthetic and “emotional” inspirations, as the writer relays:

There was an underground club called Cellblock 28 in New York that had a very hard S&M night. No drink, no drugs, they played it very straight. It was the first time I ever saw people pierced for fun. It was the first time I saw blood spilt. The austere atmosphere definitely informed Pinhead: “No tears, please. It’s a waste of good suffering!” 2

I invoke the dreadful Order of the Gash for a reason. In warning you away from the sadists, dominants, and tops who prioritize the “optimization” of skill and technique over safer, more connected play, I see the Cenobites as inspiration for us all: they’re doing it for the love of the game, and isn’t that the spirit of leather? These sexualized yet sexless adrenaline freaks have been playing for so long that they no longer differentiate between pain and pleasure (let alone consent and violation3). There’s no profit-driven perversion of “health,” “community,” or “intimacy” here, just good, clean fun!

While last time I wrote that the SDATs that you and I are after aren’t optimizers, I’d like to expand the premise of this post so we can talk about what they do instead: safer sadists, dominants, and tops don’t optimize. They do build skill individually and collectively out of a desire to engage in more risk-aware and pleasurable play.

May 22, 2024

David Davis 46, part 7

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 6.

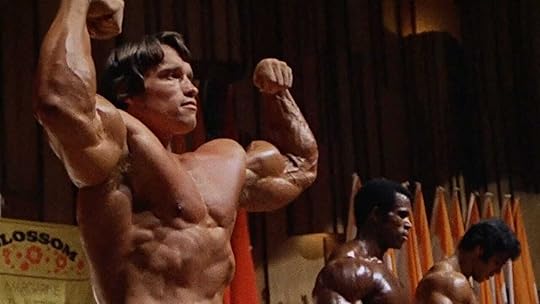

Of course I wish I had a normal body, but it’s becoming more difficult to separate what that could look like from the rituals of normalcy I see around me. The regimens that produce this normal body—one that is thin, buff, or powerful, but ideally a combination of the three—have become increasingly inextricable from the body itself. Had I that normal body, I would no longer live to stay alive. Instead, I would live to attain an ever-evolving suite of health goals (many of which have little to do with overall longevity). Is that any better, to be freed from the tedium and time-suck of disease, only to become a Sisyphus of another sort?

Hustle and grind, gain and cut, crush and shred, maximize and master. Having been sick, and occasionally disabled, for most of my life, the concept of health optimization sparks a furious fascination within me, and it’s only gotten worse as the optimizer’s influence has grown. For the optimizer, the body is not a living thing. Not unlike a corpse on the pathologist’s table, it’s an object that, with the proper technology and data, can be known, refined, and even perfected. Institutional divestment from healthcare, general austerity, and the myriad oppressions of non-normative bodies in a failing consumerist culture have resulted in this: the repackaging of lack as an opportunity to bootstrap, which is then, most cruelly of all, sold back to us as a luxury good1. If you’re not furious, you’re not paying attention.

Now, the optimizer is far from irrational. Even more than balanced blood sugar or faster splits or boosted mitochondrial function, their reward is a sense of control and the promise of conformity, which come at a premium in late capitalism. Health optimization can improve your literal health, but quality of life runs deeper than what we as individuals can dictate; we all know, intuitively if not otherwise, that thin, healthy, white people are treated better and afforded more2. This context incentivizes buying into the myth that it’s possible manage your body to the extent that your environment can no longer affect you. Forget plummeting food, water, and air quality, lack of equity in education and medicine, or endemic microplastics—if you buy the right fits, chug the right shakes, do enough reps, and run the right functional tests, none of that has to be your problem.

Like the microplastics in our bodies, the optimizer ethos permeates our culture—social/media, policy, commerce, you name it. This is by design: American capitalism (ableism 🤝 racism 🤝 eugenics) puts the onus of survival on the individual, which means it’s your fault if you’re sick, and doubly so if you stay that way. Even if you aren’t sick, you still must be a competitor, not in order to achieve personal satisfaction or even material success, but to just get by. “Survival of the fittest” is not a dictum or a destiny, but rather a description of conditions, and its misconstrual is a prime example of this ethos’ entrenchment in all our lives.

Which brings me to this edition of my guide for vetting sadists, dominants, and tops: why would leather spaces be exempt from the seduction of optimization, which creates a commodity out of health (as well as various nebulous notions of wellbeing, wellness, and hygiene)? Especially now that leather has proven to be just as vulnerable to appropriation, co-opting, and commodification as any other subculture?

If anything, the optimizer brain worms may have an even easier time finding purchase in our scene. Because in leather, we don’t just value skill, power, precision, discipline, and control, and the ego required to accomplish them—we fetishize them! We want our SDATs to know what they’re doing (and to be absolutely insufferable about it). So how do we know when that desire for more knowledge and greater technical skill has crossed over into optimizer territory, a place where risk management and connection take a back seat to ego? We may know that safer sadists, dominants, and tops don’t optimize—so how do we use that information to weed out the SDATs who are lost in the sauce?

More on that next time.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Variations on this theme include the tradwife, which is super hot right now.

2I include “white” here because of the centuries-old racialization of health and weight, about which you can learn a lot from Sabrina Strings’ Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia, Da’Shaun L. Harrison’s Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness, and C. Riley Snorton’s Black on Both Sides: A Racial History of Trans Identity.

May 10, 2024

David Davis

The more I read about gay life during the early years of the AIDS epidemic1, the less lonely I feel.

Perhaps I haven’t earned that loneliness, being privileged to have friends that I trust will care for me when I need them to. But COVID has made my world smaller, less spontaneous, more exhausting. I rarely go out anymore, because masking at most clubs and parties is cumbersome and of course not 100% effective. Two bouts with the virus have damaged my already compromised immune system, making one of my favorite hobbies, promiscuity, more onerous than the adventures it promises. Even if COVID were eradicated tomorrow, I’m painfully aware of every potential apocalyptic pony waiting to flee the barn. I hoard medication, obsess over mucus membranes, and agonize over pricy prophylactics, all the while resisting a growing revulsion at the thought of other microbiomes, human and animal alike.

But then I think of the gay people living during and immediately prior to my childhood who also feared contact with other living beings, dreaded the doctor (if they could find one to treat them), and raged against the CDC and FDA and the US government and all the other governments, besides. At each epidemiological encounter with loss, deprivation, or injustice—whether personal or witnessed through social media—I think, There is a precedent for this. It’s cope, but it’s also true. When I can’t fuck, party, breathe, seek healthcare, or move through the world as I would like to, I think of writers of a certain era who wrote about life with or surrounded by HIV/AIDS: Andrew Holleran, Essex Hemphill, Guillame Dustan, Hervé Guibert2, David Wojnarowicz, Reinaldo Arenas, Gary Indiana, Bob Glück. If they could live with it, so can I, I think, choosing to forget, for the moment, how many of them didn’t survive.

Comparing HIV and COVID-19 as social phenomena, public health failures, or symptoms of white supremacy’s colossal destructive force is a tricky business, not least of all because HIV hasn’t gone anywhere. We ought never forget that the differences between them are stark—I personally do not attend a friend’s funeral every week—but then, so are the similarities. Like all illnesses in a world in which healthcare is not a human right, they gravitate toward populations made vulnerable by their relative distance from capital. Immune-trashing viral diseases that could be mitigated, contained, or even eliminated if those in power cared to make the effort, HIV and COVID are, as we say about mismatched eyebrows, sisters rather than twins.

The image at the top of this post is from Nicholas Ray’s breathtaking In a Lonely Place, a film noir starring Humphrey Bogart as a Dixon “Dix” Steele, a down-on-his-luck screenwriter cynically seeking his next payday among the barflies and mercenaries of 1950s Hollywood3. His desire to write is stymied by the very industry that gave him his earlier success, and his resulting misanthropy—which manifests as an indiscriminately violent temper—prevents him not only from being satisfied in his work, but from finding happiness in the people around him. Why write at all?

Old Hollywood is good for movies about frustrated writers doomed to much worse than professional failure: Leave Her to Heaven (1945), Sunset Boulevard (1950), The Bad and the Beautiful (1952)4. Lining them up now, I can’t help but notice their chronological placement between the second World War and the arrival of New Hollywood in the late 1960s. Their shared themes signal a post-war existential crisis, perhaps, for working artists in the aftermath of the Great Depression and the rise of McCarthyist repression. Despite our differences, I see myself in these fictional writers, as I see myself in the all-too-real writers of the first AIDS generation: artists whose personal circumstances force them to doubt the future. Why write at all?

I have written three books, two of which—the earthquake room and X—are published. Inside me are many more, and it is my greatest wish to make and share them. But if you want to know the truth, I don’t think I’ll have the chance. With current and incipient pandemics, climate collapse, rising fascism, and the foreign horrors in which my country is implicated, I fear the window for that kind of writing life, let alone career, is closing. I’ll get out one or two more, I suspect. After that, the writing, if and when it happens, will stay with me.

As sorry for myself as it makes me feel, failing to obtain a certain kind of career in a certain kind of consumerist economy would be no tragedy. But if there is a world after the fall of the American empire—and I hope very desperately that this happens sooner rather than later—there is little reason to think I’ll make it there, which leaves me at something of a personal impasse. I will keep writing until I can’t anymore, but how? To what end? For whom? The work of solidarity and survival is cut out for me, but as for my vocation…well…there are more questions than answers.

The more I read about gay life during the early years of the AIDS epidemic, the more I understand that I cannot only look to those writers for the lives they lived. I must also look to them for the deaths they died, all of them characterized by fear, suffering, and, yes, loneliness. In my better moments, this reassures me.

If you have a few dollars to spare, please help Lina and her family evacuate Gaza. Every life is priceless.

Thank you for reading and sharing. Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Buy my book. Learn the history of this newsletter.

1By which I mean the 1980s through the mid-1990s, although evidence suggests a decades-long emergence, including an illness referred to as “junkie flu” or “junkie pneumonia” that was killing homeless IV drug users in New York in the 1970s.

2And through him, his lover, Michel Foucault.

3Bogey is so fucking good. Peel back his snideness to find a yearning lover, not unlike Casablanca’s Rick Blaine, at your own risk. Beneath him lurks yet another man: a shark-eyed killer with a rage so terrifying you forget it’s trapped in the body of a middle-aged chain-smoking welterweight.

4If you’re looking for a worthwhile homage, the Coen brothers’ Barton Fink (1991), starring sweet baby angel John Turturro, is excellent.

May 2, 2024

David Davis 46, part 6 ½

Last time, I wrote about the difference between fantasy and reality in terms of SM. I also wrote about fantasy and reality terms of safety, and the way that post-traumatic fantasies of control can make it more difficult to assess risk and build intimacy, two skills crucial for protecting ourselves and those in our communities.

TL;DR: if your SDAT cannot tell the difference between what they desire/fear and what is actually happening/may happen, they are not prepared for safer play—especially if that play is heavy.

April 29, 2024

David Davis

“I will kill you.” Done with the right kind of deadpan, this is the funniest thing you could say under the circumstances.

“I will fuck your husband.” If I haven’t already!

“Wanna see my cunt?” Asking this as a means of offering “proof” only reaffirms their logic, but asking this an act of sexual aggression (that they implicitly asked for, by the way) is great.

Hold eye contact while peeing my pants. A last resort since this one actually inconveniences you, but the catharsis appeals to me. It seems that most doctors and scientists, even ones that are trans-informed, haven’t cottoned on to one environmental reason why trans people are more prone to health issues like UTIs: a lot of us are afraid or unable to use public bathrooms.

Look around with confusion with my eyebrows screwed up like Jim Carrey, then point at myself, mouthing, “Who, me?” I’m imagining her getting increasingly frustrated as you meander around the bathroom pointing at random stuff—other people, empty stalls, your reflection in the mirror.

The Jojo Siwa seppuku dance. Karma’s a b*tch and so am I.

“Do you have a moment to hear about our lord and savior, Jesus Christ?” There’s an argument for having some JW literature or Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health on your person while out and about.

“Do you when you you you when you when when wheeen when when you—”

Pull her hair. I think violence is appropriate in a lot of situations, including this one. Sometimes more extreme measures are called for, but getting your hair pulled is so demeaning, and there’s something about the way it’s gendered as something done between women that just does it for me. I’m more of a woman than you ever will be, bitch!

“You aint even the 💨” I don’t know.

“Okay, ugly.” Short, sweet, and to the point.

If you have a few dollars to spare, please help Omar and his family evacuate Gaza. Every life is priceless.

Thank you for reading and sharing. Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Buy my book. Learn the history of this newsletter.

April 24, 2024

David Davis 46, part 6

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, and Part 5 ½ .

The party was almost over. I was gathering our things in the locker room when someone approached me from behind. As if he and I were elsewhere, fully clothed and totally sober, Nes politely introduced himself and complimented my book. A perfect gentleman, but unintimidated—I liked that. After a brief and friendly chat, we went our separate ways.

Though Nes and I reconnected on Grindr, our mutual narrative began at that party: the Bawdy locker room, usually the site of hazing-themed gangbangs, was our meetcute. It was only months later, when we were properly dating, that he revealed that he had watched me for hours that night, describing my movements with the detail I now recognize as a function of his impressive recall1. I had been caught red-handed in the act of living, and although everything he relayed—where I stood, what I did, who I spoke to—was doubtlessly true, I could remember almost none of it.

Our meetcute became a shared experience for which I wasn’t fully present, a rearview depersonalization. Had I even been there, at Bawdy, if so little of the night had returned home with me? I was reminded of dreams I had when I was a child: my eyes wouldn’t open all the way, forcing me to crane my head like a parrot in order to see what was happening around me. What I wore, when I sat in the hot tub with Jade, how I glanced at him without knowing we would soon know each other—to witness my own absence through Nes was embarrassing, destabilizing, and very hot.

If you attend a sex party, you do so with the intention of being observed by strangers. This is not a bug of (semi)public sex, but a feature, which you must admit to yourself if you’re going to have a good time. As a Bawdy volunteer2, I was recently called to explain this to a nervous newcomer. “What do I do if someone is looking at me and I don’t like it?” they asked, scanning the dim over my shoulder.

Dykes have been throwing sex parties for far longer than I’ve been alive, but most that I’ve encountered have not done what Jade and Daemonumx are doing with Bawdy, their queer bathhouse party, and Bruise, their public leatherqueer party, which is establish as a social baseline an integration of dyke and fag approaches to consent, cruising, and safety. For many dykes, there is a learning curve for public sex because of the restrictions—as well as the protections—of so-called “female socialization”3. To boldly reconfigure one’s understanding of safety in order to attend a sex party organized by people who refuse to entertain gender policies, requirements for government names, and STI monitoring is no mean feat4. But to cruise necessarily means exposure to unexpected people, unreciprocated desires, complicated feelings and conflicts, activating situations and environments, and, enmeshed with all these, breathtaking possibility. To cruise is to be more free, and freedom is always undertaken as risk.

What Nes did only became “stalking,” as he and I call it, after I learned about it, when my awareness transformed his attention into a shared fantasy between people who straddle straight, dyke, and fag worlds, as we transsexuals often do. But even if he had never told me what he did, the act would have remained a neutral one. Being the subject of someone else’s interest or desire, even if the content of those desires is violent—and with him, it definitely is—does me no harm whatsoever.

As I told Bawdy’s nervous newcomer, the responsibility of the party itself is to intervene when someone in attendance is threatening or hurting someone else. “If anyone fucks with you,” I reassured them, “come get me and we’ll take care of it.” But I reminded them that they had come to enjoy public sex with and among other queer people; that discomfort is not the same thing as harm; and that to be known in ways that aren’t always under our control is, in fact, why we were all there in the first place!

In Sexuality Beyond Consent: Risk, Race, Traumatophilia, Avgi Saketopoulou writes:

…we do not know what our unconscious will produce or, thus, what we will encounter. Therein lies also the difficulty with which one must contend: even as the unconscious is never “ours,” in that its force is not under our “command,” it is also of us, which means that we are responsible for its effects in the world.

As screen, cipher, and/or obstacle to the psychoanalytic concept of the unconscious, the fantasy is one thing and its expression is another (kinda sorta). Which is to say that I don’t believe that I need to have been threatened with a knife in order for my arousal at the notion of knifeplay to be ethical. In fact, I don’t believe I need to impose an ethics on my arousal at all, which appears spontaneous and unreasonable to my conscious mind (unlike my behavior, over which I do have control, and for which I must be accountable in any community worth its salt).

This doesn’t mean the distinctions between fantasy and reality don’t matter to me, or that I can’t sympathize with someone, like Bawdy’s nervous newcomer, whose past experiences and socializations have made them wary of being perceived in stigmatized erotic contexts5. As someone who has been sexually assaulted in spaces designated for queer public sex, I understand the instinct to clamp down, draw lines, and exercise a fantasy of control because it feels safe, even if it actually isn’t. Gone uninterrogated and untreated, PTSD manifests as theater: it feels terrible, and it doesn’t even work.

Nes knows, as I do, that our way of relating to each other is right because it comes naturally to both of us. And here, of course, is yet another opportunity to unpack natural and what it means: one reason why Nes’ gaze is so exciting to me is because I have been stalked by men I once knew and trusted, men for whom my humanity vanished when they got angry. It was their terrifying behavior, not their fantasies, that obliterated the consent I had once extended them, and, in a few instances, made me feel as if pleasures like public sex, S&M, and community were no longer available to me. It’s only be resisting fantasies of my own control that I could begin regaining that sense of safety.

I’m sorry to announce another two-parter in this series, but I needed this preamble in place before digging into why safer sadists, dominants, and tops know the difference between fantasy and reality. More on that next time.

Thank you for reading and sharing. Find me on Twitter & Instagram, get my second novel here, and learn the history of this newsletter here.

1Sorry, I’m a pothead! is the expression I picked up from Bambi to explain my relative lack of memory. Perhaps this is why I’m attracted to people who abstain (Jade, like Nes, remembers everything).

2Between COVID and malaise, I’ve pretty much only been going to parties thrown by my friends, so naturally I get roped into helping.

3This is one reason why the “male/female socialization” binary fails: birth assignment cannot account for our gendered experiences (not to mention all of the other kinds). Jade and I were both assigned female at birth, and yet for reasons of race, ethnicity, class, family dynamic and configuration, and much more, we have sharply divergent experiences of our genders. We’re not gay together because of our birth certificates. We’re gay together because we live gay lives. “We who are socialized like this experience that”—girl, who the fuck is we?

4Because these practices are, for various yet interlocking reasons, transphobic, homophobic, racist, whorephobic, ableist—you name it.

5When I am surrounded by straight people, their gratuitous flaunting of their state-sanctioned sexuality collides with my weird body to generate what I experience as an intense and uncomfortable sexual pressure. Why is it that I must abide that discomfort, while those who feel it in contexts where eye feel safer can claim harm or abuse—often while having opted into those rarified contexts in the first place?

April 18, 2024

David Davis

I’ve somehow made a dent in my list since last time, but the library holds, ARCs, and night stand staples continue to accumulate. There are too many books! And yet there isn’t enough money to go around for working writers, especially for those of conscience!

As the institutional divestment from writers of all kinds continues to accelerate, I hope you’ll keep buying books, going to readings, and patronizing your local library. It’s good for you, good for artists, good for everyone.

In the meantime, here are a few notes on some of what I’ve read this year so far.

Mobility, by Lydia KieslingMobility, “a brief segment of the history of global capitalism and climate change,” per the Washington Post, is the story of the credulous Bunny, the white, elder-Millennial child of American diplomats who muddles her way from a dead-end degree into a career in the marketing branch of a Texas oil company.

Bland, docile, and only occasionally likable, the aptly-named Bunny is defined by a skin-crawling passivity at once alien and implicating. “The earth is getting warmer,” she gingerly offers in response to the regurgitated propaganda from one of her industry’s many shills. “It’s, like, a fact. Species are going extinct every minute?” But though she encounters alternatives to collaboration—like her sister-in-law, Sofie, a no-bullshit journalist who knows which way the wind is blowing1—her complicity is as inexorable as the capitalists she serves.

Like The Golden State, Kiesling’s debut novel, Mobility is powerfully readable. Unlike The Golden State, which only foretells of a more general American decline, Mobility presents a hair-raising timeline—one chillingly syncing with my own lifespan—of incipient climate collapse. Though a bildungsroman in the literal sense, Mobility can be read in multiple ways: as a clarion call to action, while there’s still something to be done; as an Acme-style DETOUR sign hovering like a mirage over a bottomless chasm; and as a cautionary tale for those who would choose momentary comfort over everything else.

An Honest Woman, Charlotte ShaneA lot of compulsive behavior can be understood as an attempt to learn the unlearnable, to teach yourself something you’re failing to learn. Whatever insight you’re chasing might be categorically unknowable, or beyond your specific capacity, or maybe you trap it but almost instantly lose it, and so track it down again, committing the same mistakes while you do. The mistakes can become an element of the sequence, the superstition. The mistakes might not be distinguishable as such. Maybe, no matter how inefficient or painful, they’re not mistakes at all.

With her new memoir, excerpted above, Charlotte Shane charts a through-line from her formative years as a girl among boys, to her adulthood as a lover of men, with all the intelligence, humor, and sensitivity we’ve come to expect from her. An unconflicted yet rigorously self-aware heterosexual, Shane and her refusal to apologize for herself—as a woman who desires pleasure; as a sex worker with an unquenchable interest in other people; as a person in pursuit of experience—has never been more refreshing.

Why do I want what I want? Do what I do? Be what I am? In seeking to answer these questions for themselves, the best memoirists offer a schema for those of us similarly preoccupied. This is why genuine honesty, of the sort Shane seems to effortlessly exhibit, is so profound: the truth is only known when someone is first brave enough to name it.

Koolaids: The Art of War and The Wrong End of a Telescope, Rabih AlameddineIrascible in tone and intercrural, one might say, in form, Alameddine’s debut novel, Koolaids, is set in both San Francisco and Beirut, moving fluidly between characters shaped by the AIDS epidemic, American racism and homophobia, Western imperialism, and the Lebanese Civil War. A Christmas gift from Bambi, Koolaids’ arrival felt like a queasy stroke of luck, as both:

A welcome queer historicization of various twentieth-century Middle Eastern conflicts, about which I know very little, at a time when the Zionist entity had already slaughtered nearly 20,000 Palestinians since October 7.

A touchpoint for my next project. In his Rechy-esque novel of vignettes, conversations, diary entries, film scripts, and reportage, Alameddine produces a compellingly choral narrative in which it can be difficult to determine which character is speaking when. And yet it plays. I can’t be more specific about its use to me, but suffice it to say I was grateful for what this format does and reveals.

Thus Alameddine-pilled (who isn’t??), I rushed to Thriftbooks.com and ordered another of his books at random, without reading the synopsis (I like to surprise myself). When The Wrong End of a Telescope arrived in the mail, I dove in without delay. It was only when I realized that the first-person novel’s protagonist was a trans woman that I checked the endorsements—the most prominent from Susan Stryker herself.

Despite Stryker’s sign-off (which includes her name in the acknowledgements), I was ultimately disappointed in Telescope’s use of transness. To be sure, the story of Mina, a lesbian Lebanese doctor who journeys from America the island of Lesbos2 to help the refugees fleeing the Syrian Civil War by boat, is sensitively rendered; there is no explicit transmisogyny, that I can clock, on the part of the author. What’s more, the cis characters, most of them refugees—particularly Sumaiya, who under Mina’s care conceals her terminal cancer diagnosis from her family so as to ensure their safe passage to Europe—feel painfully, complexly real, their lives rich with hope, fear, humor, resilience, and righteous outrage at their unjust deracination from everything they know.

But because Mina’s transness has almost no bearing on her life (other than her estrangement from her natal family, a process that mostly remains in her past), I began to doubt the authenticity of Alameddine’s other characters, who otherwise felt so real to me. Though Mina came out in 1980s America, the garden variety anxieties of trans life, particularly for women, never really materialize. We get the sense that she doesn’t always pass—a safety concern for any trans person, particularly one who is away from home alone—but the only instance that she’s clocked seems like more of a setup for another character’s (incidentally quite moving) anecdote than a slice of the transsexual experience.

I finished Telescope with so many questions about its main character: what does Mina’s trans community in the States look like? How do her medical needs inform her time in Lesbos? Does she worry about hopping planes, crossing borders, and negotiating aid with police, bureaucrats, and disaster tourists? Perhaps Alameddine didn’t want to include these details for fear of distracting from his other characters, the casualties of a brutal civil war, whose stories are the novel’s primary focus (and rightfully so). Perhaps he did not want to risk stereotyping or 101-ing an experience he does not share. Perhaps there’s another reason I haven’t thought of.

In any case, I finished the book wondering if Mina’s transness is a plot device rather than a facet of a fully realized character—and in my humble opinion (my apologies to the great Stryker!), Telescope suffers for this uncertainty.

Horse Crazy, Gary IndianaGary Indiana’s third novel is about a white gay writer, age 35 and living in New York (like me 👀), who is plagued by Gregory, a beautiful younger man who may or may not be straight, may or may not be a junkie, may or may not have HIV, and may or may not return our protagonist’s increasingly desperate affections. They never fuck. They often fight. Meals go uneaten, books unread, and work undone, and yet nothing really happens except for our protagonist’s exquisite dissatisfaction, the potency of which becomes more poisonous by the day.

After reading Indiana’s Do Everything in the Dark last year, I told Jade that he and I are the same, which is what I always say when I enjoy another author’s work. After reading Horse Crazy, plus Indiana’s recent interview with the Times, my sense of identification has only grown. A fag obsessed with hustlers, true crime, and unattainable beauty, a Truman Capote meeting Thomas Mann? Like, bring bring, hellooooo? Who can introduce me to Gary???

Cuckoo, Gretchen Felker-MartinFollowing the runaway success of her debut novel, Manhunt, Gretchen Felker-Martin is returning this June with the vivid, relentless, hair-raising Cuckoo, about a group of queer and trans kids escaping the conversion camp from hell. A Carpenter-meets-King fantasia made all the more horrifying by its relevance to American LGBT youth at this moment, Cuckoo pushes queerphobic notions of monstrosity and contagion to their limits with gratuitous violence and terrific feeling.

I have a LOT more to say about this remarkable book, but I’m hoping that someone will pay me to say it. My completed review is cooling on the windowsill as we speak, so if I don’t get any bites, I’ll share it here for all of you3.

A Painter of Our Time, John BergerMy new book, Casanova 20, is about a painter at the end of his life. To prepare for the editing process, I returned to this epistolary4 comfort read, a pellucid—though only occasionally transparent—meditation on the meaning and purpose of art, artists, and art for the people.

Despite the ghosts that haunt protagonist Janos Lavin, a Hungarian communist exiled to London following the Second World War, Painter always soothes me; it has a quality that my friend, Liz, calls coziness, which often characterizes quiet novels about domesticity and process5. Perhaps this is because Painter is about an artist, like me, while also being about a painter, unlike me. As Janos writes in his diary:

I am a painter and not a writer or a politician or a lover because I recognize a climax in the way two hanging cherries touch one another or in the structural difference between a horse’s leg and a man’s leg. Who can understand that?

The first time I read this passage a few years back, I wrote Who indeed! in the margin. In 2024, the annotation stands. I can understand that, and yet I can’t! The older I get, the more I find myself in artists who are not writers; Berger’s contrast generates a voluptuous charge that never fails to give me pleasure.

A Short History of Transmisogyny, Jules Gill-PetersonGender as a system coerces and maintains interdependence, regardless of anyone’s identity or politics. Trans misogyny is one particularly harsh reaction to the obligations of that system—obligations guaranteed by state as much by civil society. The more viciously or evangelically any trans misogynist delivers invectives against the immoral, impolitic, or dangerous trans women in the world, the more they admit that their gender and sexual identities depend on trans femininity in a crucial way for existence…The collective power of trans-feminized people, including trans women, lies in how many others rely on us to secure their claim to personhood.

In the last year or so, I graduated from dog-ears and inky exclamation points to a more grown-up version of marginalia: shredded bits of Post-Its slid lengthwise into pages I’d like to return to later. Nowhere has this change been made more evident than with my copy of Gill-Peterson’s latest, which now resembles the flank of a multicolored hedgehog.

Despite the slimness of this volume, there is so much in A Short History to consider—not just Gill-Peterson’s insights into the global structuring logic of transmisogyny here and now (as well as there and then), but how this logic might be reimagined within a post-scarcity feminism in which exceptional femininity is no longer suppressed.

These innovations are already happening—Gill-Peterson offers Latin American mujerísima, a trans-feminist identity/affect/movement that envelops trans-feminized people while resisting white supremacist, imperialist, cis-centric transness, womanness, and legibility—but they will require more from us collectively, including a radical abundance mindset. “How might trans women lead a coalition in the name of femininity,” Gill-Peterson asks, “not to replace or even define other kinds of women, but to show what the world might look like for everyone if it were hospitable to being extra and having more than enough?”

Phew!

While I don’t have the time to blurb all of the ARCs I receive, I do my best to promote the interesting ones, especially if they’re by other trans people. Here’s what’s next on my list, including a few to look out for this year:

Sexuality Beyond Consent: Risk, Race, Traumatophilia, by Avgi Saketopoulou. I’m way behind on 2024’s hot-ticket item for sex nerds. It’s been languishing in my stack, but I have a feeling I’ll be getting to it soon. If I’m a good girl, I’ll finish it before wrapping up my current series on vetting.

Failure to Comply, by Cavar. This “epistolary, time-flipped dreamscape” follows I, a biohacker on the run from an authoritarian government hell-bent on mining their memories. By all signs ambitious and original, Cavar’s newest is sure to be of interest for anyone into “trans dystopia carceral state ~vibes~ and themes,” as they wrote me.

Feminism Against Cisness, ed. by Emma Heaney. Heaney’s new collection of writing resists a fallacy that most take for granted: that assigned sex determines sexed experience. “To say sexual experience is material is different than saying sexual difference is natural or eternal: far from it,” she writes. Featuring work by Cameron Awkward-Rich, Kay Gabriel, Marquis Bey, Jules Gill-Peterson, and more, Feminism Against Cisness is bursting with promise. I’m excited to read it.

Still Life, by Katherine Packert Burke. If the gorgeous cover is any judge, Packert Burke’s debut is sure to be a breath of fresh air. As I wrote above, I love a novel about process, and Still Life is about, at least in part, a writer grappling with her next book (not to mention her stalled career). There’s plenty of transsexual drama, too. Make sure you pre-order, girlies.

The Song of the World, by Jean Giono. A recommendation from the aforementioned Liz. So far it’s reminiscent of a French Cormac McCarthy—right up my alley, in a way I never anticipated. Liz is good for that.

New Yorkers are probably already aware of this fundraiser for a local woman who was grievously harmed by her partner. If you have any cash to spare, please send it her way.

Thank you for reading and sharing. Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel here. Learn the history of this newsletter here.

1Which the WaPo reviewer refers to as the book’s “necessary but exhausting leftist,” which I think is so outrageous considering its subject matter. Moderates really do view people of conviction as tiresome, I suppose.

2Say that five-times fast.

3That’s the nice thing about having a newsletter. If no one wants to publish me, I’ll do it myself :)

4I consider diary/journal novels epistolary but I actually don’t know if that’s true.

5It’s also the least sexually awkward work by Berger that I’ve yet come across. He was so progressive in terms of sex, and yet non-cringe lovemaking was often beyond him, IMO!

April 15, 2024

David Davis

The humidity brings the darkness close, like a cat sleeping against your body. The air gusting from the train station becomes clammy, gains velocity. Urban petrichor—oil, mildew, river—suddenly overwhelms the quotidian fragrances of piss and rotting food. A few moments before water begins stubbling the pavement, I think of my umbrella, at home on the shelf by my door, flanked by weed gummies and N95s.

It descends like a veil, its rush quelling the anxiety of having been caught unawares: It’s too late now. Accept your fate1 . Through my glasses, windows and wristwatches and wrappers take turns flashing white, losing and regaining their composure as I hurry back to my apartment. Every surface boils with new prisms for the light’s piercing, a dilemma for the astigmatic who has not yet let go and let God. I learned the word surrender from a skywriting witch, and so have always associated the concept with looking upward.

The world is getting hotter. I’ve known this since childhood, but it became something I think about on a daily basis in the late teens, when wildfires first began keeping Californians indoors for weeks—even longer—at a stretch. My home, stolen land built on borrowed time, is drying up. My city, meanwhile, is melting, as Margaret Hamilton might say2. If only it was something I could know second-hand, through the observations of native New Yorkers. But I know it myself, even after having only lived here for five years. The seasons are softening into each other, though the highs continue to spike. More water, more heat, more closing darkness.

Like you, I do what needs to be done. But for some reason, the cyberdystopias of my youth are where I turn for relief: the monsoon skyline of Blade Runner (1982); the violent petri dish of Neuromancer’s Tokyo Bay; the digital mists of Transmetropolitan. Twentieth-century sci-fi lent new dimension to the noir’s dark precipitation, and to my displeasure, I move through it in real time. That is what a future could look like, I think, desperately searching for something between miracle and horror, though I can’t see a thing, blinded as I am by the storm.

I know I can’t reassure you, though I seek reassurance for myself. Perhaps it’s most meaningful to offer you my company. I’m here. Are you?

DecrimNY is fundraising to cover transportation, meals, and direct support for a May 15th trip to Albany, where they will be advocating for the Stop Violence in the Sex Trades Act. Please donate if you can.

Thank you for reading and sharing. Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel here. Learn the history of this newsletter here.

1Twitter recently told me that this sound is indistinguishable from that of chicken frying.

2Did you know that Betty Danko, Hamilton’s stunt double in The Wizard of Oz (1939), was severely burned during the “Surrender Dorothy” skywriting sequence? She was hospitalized for 11 days and her legs were permanently scarred.

April 8, 2024

David Davis 46, part 5 ½

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, and Part 5.

In her recent piece about seminal lesbian film Desert Hearts (1985), Drew Burnett Gregory does a close read of a sex scene. The closeted Vivian (Helen Shaver) is seduced by Cay (Patricia Charbonneau), who talks her way into her hotel room and takes off her clothes as Vivian moves through increasingly unconvincing postures of refusal. Although Vivian asked Cay to leave just a few minutes before, they’re soon making love. As Drew writes:

Watching this film in 2024, it would be easy to dismiss this exchange as a product of its time — either the 1950’s setting or 1980’s when it was made. But I find it far more interesting to acknowledge that while a no should always be taken as a no, there’s still a truth to this moment. Many queer people need a push — whether it’s someone being sexually forward or someone giving an unprompted nickname or, in my case, a queer woman suggesting I try her lipstick long before I was ready.

Power, as Drew writes, isn’t a math equation. It’s the matrix within which such equations occur. Vivian and Cay’s sex scene takes place at the nexus of queer and straight courting mores; in the wake of onscreen heteronormative ravishment fantasies; is contextualized by the intense social stigmatization of queerness (specifically in 1950s Reno); and is complicated by a character’s inability to say yes to what she wants without help. But when filtered through mainstream discourses about sexual consent, this scene loses the nuance that makes it authentic and the depth that makes it specific to a love story between mid-century women of different ages, experiences, and sexual identities.

In the 1950s, anything resembling Vivian and Cay’s sex scene wouldn’t have been permitted outside a dirty movie theater. Today, something like it could easily be found in Oscar bait1, but it wouldn’t last a second in a consent training, whether in a corporate office or a queer infographic. I’m not the first person to point out that those mainstream consent discourses, particularly the ones serving government, business, or legal interests, are focused on the getting of consent, as if it were the receipt you present while leaving Costco as proof you aren’t stealing the flat-screen in your cart.

While appearing to recognize that various affirmations of “consent” can be cajoled or even coerced out of someone, the mainstream response to sexual consent violation is to define consent in increasingly narrow terms to which we can hold everyone (especially survivors). What results is a framework that prioritizes would-be violators over anyone else (especially survivors). These are the people that brought you Consent is sexy and enthusiastic consent, or who see low numbers of rapist convictions and think, We need more people in prison, not, We need less sexual violence and more resources allotted to those who survive it.

If we can learn anything from No means yes, yes means anal, it’s that the special phrase that prevents sexual assault (by pretending it’s all caused by misunderstanding) cannot exist in a context where consent is the exception rather than the rule.

There are no words, situations, or people that are inherently safe or unsafe. That’s why safer sadists, dominants, and tops want your consent—and understand that it’s complicated.

April 2, 2024

David Davis 46, part 5

Read Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, and Part 4.

Another day, another book about sexual consent—if such a thing is even possible! For The New Inquiry, Sohum Pal reviewed Manon Garcia’s The Joy of Consent: a Philosophy of Good Sex, which “asks if consent could be retooled to serve the ideal of ‘good sex,’ sex which is not only pleasurable, but also ‘a moral good.’”

Yikes! I haven’t read Joy myself, so I’ll rely on Pal to do the heavy lifting for me, beginning with Garcia’s muddled logic: “Of predominant concern for Garcia is the condition of patriarchy, but one might easily extend the same question to the logics of colonialism and racism, of ableism, or of economic class (Garcia never arrives at such questions…).” And then there’s the limited scope: “Garcia seems somewhat mired, perhaps because her prescriptions rely on the thin premise that there is a unitary act called sex, a denial of the possibility that any sex between any two (or three or four or more) involves new negotiations of preferences and practices.”

Pal notes Garcia’s inclusion of BDSM in a historical survey of philosophies of consent, which leads directly, he writes, to her questioning whether the social hierarchy allows for any consent at all, ever, period. For Garcia, the tricky issue of sexual consent is a nut to be cracked—until an actual redistribution of power is the nutcracker, in which case the entire exercise suddenly falls into question.

BDSM’s various consent frameworks often pop up in texts about sexual consent, but rarely are their logics taken seriously by the academics that put them there—how can they, while dismissing sex workers as drivers of patriarchy (speaking of chestnuts…), as Garcia does? For her, BDSM is an abstraction within the greater abstraction of consent, not a real thing that real people do (unless they’re mentally ill, but this naturally disqualifies them from the category of “real people”).

Here’s the thing: any narrative that frames sexual assault as an aberration rather than as deeply normalized will only ever root around in the mud of its own normalcy. A failure to engage in the material contexts in which questions of consent arise results in books like Joy, which, per Pal, “[claim] to be speaking in universalisms but only [deploy] evidence from heterosexual, gender binary particularities”1. Even if a white-washed, straight-laced version of patriarchy is the problem, as Garcia argues, the solution will not be discovered by those served by it.

As I mentioned last time, there’s a strong argument to be made that the connection, presence, and community required to pull off a safer SM practice means that that practice is extremely consensual, even more so than vanilla sex—not by necessity, but by design2. In positioning BDSM as little more than a foil of the mystical “moral” (🤮) sexual encounter, the thinkers churning out claptrap like Joy not only fail to solve for real sexual consent, but reinforce the reactionary and conservative strains of thought animating its dominant discourses. As Pal writes:

“Consent is a heuristic for assessing the legality of a sexual situation, but it cannot be a heuristic for understanding what is desired or desirable sex. This is the difficulty with desire—there are no intellectual shortcuts or heuristics to be taken. Rather, in understanding our own desires and the desires of others, we are forced to take a step into the darkness, complete with the risks of guessing wrongly and falling through.”

What if sexual consent isn’t to be found in normalcy? What if a bold pursuit of it is what led us to SM in the first place? What if a desire for pain, control, or stigmatized sensations and relations—in opposition to legal, consecrated, procreative, heterosexual sex—is what actually produced the advanced consent practices that you and I are currently thinking our way through?

I’m being a little provocative, but also…not? This series isn’t just about tracking down the SDATs whose habits, practices, and beliefs cultivate safer play. It’s also about divining what it is that we want before, during, and after we get it—which really matters when we’re involving other people in our desires.

It’s tempting to make a home in Garcia’s world. If only sexual consent was always as easy as yes or no. If only creating more laws to punish its transgressors would eliminate the violence bred by police, prisons, and the state. If only putting even more of the onus on survivors of sexual assault (and those slated to become them by an inegalitarian society) could unpaint this corner. But it’s not always that easy. And caging people doesn’t reduce the incidence of sexual violence. And sometimes there really is nothing that you could have said or done to have prevented that person from hurting you.

I don’t have all the answers, but I do know this: safer sadists, dominants, and tops want your consent—and understand that it’s complicated. More on that next time.

Thank you for reading and sharing. Find me on Twitter & Instagram, get my second novel here, and learn the history of this newsletter here.

1I think Pal’s language is clunky here, but you get the point.

2I am obviously not saying that consent violations don’t happen with SM, or that consent cannot exist in normal sexual contexts.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 56 followers