Davey Davis's Blog, page 6

November 22, 2024

What I've been reading and watching

What I’ve been reading

What I’ve been readingBooks

It’s been an Irish autumn for me. A friend gave me a trio of Claire Keegan’s slim volumes, as they like to call them, and I couldn’t put them down: Foster, So Late in the Day, and Small Things Like These (now a film, which I haven’t yet seen). While all Keegan’s novels and stories are melancholic page turners, each a keen and bluish dissection of misogyny, Small Things—set in County Wexford in the 1980s—is the superior specimen. She really hit her stride with Bill Furlong, the upwardly mobile son of an unwed mother who discovers the local convent’s training school for girls is a Magdalene laundry, because he is somehow a good man, and you really believe it. Inspired by the recent fanfare around Sally Rooney’s fourth novel, Intermezzo, I also listened to Conversations with Friends on audiobook. It was as dishy, diverting, and (on one or two occasions) humblingly relatable as I remember Normal People being1. Keegan and Rooney are a funny pair of spoons: the former does postmortems of patriarchy, while the latter’s characters are as preoccupied with interpersonal right-doing within the big P as they are with creating the conditions for it2.

From Ireland, I bopped over to the Caribbean, Florida, and New York City for Nights in Aruba, which took a little of the shine off Andrew Holleran for me, to my surprise. The self-centered perspectives of Dancer from the Dance and The Beauty of Men provide both charming and disenchanting looks into twentieth-century gay life with protagonists who are both saturated in and exiled from their own desire. Nights, which draws on the author’s life—from his upbringing in Aruba, to his military service during the Vietnam War, to his strained and claustrophobic relationships with his parents and sister—while often beautiful, and even emotionally incisive, suffers from a main character whose defining characteristic is avoidance. Maybe I’d have more patience for it if I found Holleran’s stand-in, a pathologically apolitical young man who prefers his family’s abuse to almost any other relationship, to be sympathetic, but his ennui wore on me. I can only take so much (literary) masochism before losing interest.

This whole audiobook thing is because I’ve started rowing four or five days a week, so I need something to listen to that isn’t Democracy Now! because I refuse to be alone with my thoughts for even an instant. Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights3, an old favorite, was only 99¢ on one app or another, so I’ve been working my way through that, although this go-around has been admittedly more of a slog. Could be the medium; could be that, due to my advanced age and thousands of hours of therapy, the tragedy now outweighs the romance. When I get sick of all the little voices the audiobook reader has to affect so I can tell the difference between Cathy and Cathy, Jr., I switch over to whatever film studies nonfiction is free or immediately available on Libby, like Harlan Lebo’s Citizen Kane: A Filmmaker’s Journey or one of the many about 2001: A Space Odyssey4.

My goal is to have read 40 books by the end of the year, and while I don’t think I’ll quite make it, I’m doing my level best with what’s on my night stand: Kaveh Akbar’s Martyr! (so far funny, good-hearted, and ambitious), Anton Solomonik’s forthcoming Realistic Fiction (more on this fascinating story collection to come), Anne Moody’s Coming of Age in Mississippi, Georg Lukács on Lenin, and my Gary Indiana backlog. Pray for me, if you’ve ever prayed5.

What I’ve been watchingFilm

A few weeks ago, Nes took me to Film Forum to see Shuchi Talati’s splendid Girls Will Be Girls (2024). While I initially resisted—I’ve never been a fan of coming-of-age in any medium—Girls’ Mira (Preeti Panigrahi) and the stellar script won me over. Set in a boarding school in the Himalayan foothills, Girls follows high-achieving Mira’s disruptive romance with another student, which her mother (a smokin’ hot Kani Kusruti) supports at first ambivalently, and then inappropriately. To say that Girls gets emotionally incestuous with it wouldn’t be inaccurate, but I don’t want to sensationalize what is, at its core, a gentle yet fearless movie about what it means for a girl to be a grown-up.

Some other 2024 releases I saw recently:

The Substance, which was so boring and pointless I wanted to walk out. Everyone who enjoys this film as anything other than a smorgasbord of practical effects is a fool! What a waste of Demi Moore.

Heretic, which was good, clean fun. I agree with pretty much everything Fran had to say about it, but you really do have to be a Hugh Grant fan for it to work, I think.

Desire Lines, a hybrid documentary that Anthology Film Archives screened for its Narrow Rooms series. The narrative sections left a lot to be…desired…but the transfag interviews were really lovely. Plus, Nes and I got in for free because we’re clocky.

Plus some older fare:

I Heard It Through the Grapevine (1982). The election was still looming over the BAM screening I went to with Jade in October. Spritely, amber-voiced James Baldwin returns to the American South to talk with old comrades from the civil rights movement, people who where there at the March on Washington and risked their lives on freedom rides, protests, and sit-ins. Directors Dick Fontaine and Pat Hartley6 intercut their recollections with archival photographs and footage of profound suffering and humiliation: a white woman dumps a jar of ketchup onto a Black man’s head at a lunch counter; firefighters turn hoses on human beings that strip bark from trees and clothing from skin (pinioned against a building, a man shields the bodies of smaller people with his own). Baldwin joins a former teacher who tells the story of being incarcerated and tortured, along with her classroom of children, for protesting school conditions in Jimmy Carter’s Georgia (Carter, who is still alive at, like, 100, is these days hailed as a hero while his handlers cast his vote in the presidential election between genocidaires); as a new generation of schoolchildren learn her story, someone in the row behind me sobbed. I don’t have the luxury to be afraid, one man tells Baldwin while speaking of his youth as a political prisoner, because my grandmother lived through so much more, and her grandmother before her; now older, he devotes his life to teaching children, and his gentleness with them is almost destabilizing. The exhausted disillusionment of Baldwin’s interviewees is certainly not inspiring, in the sanitized way we like to use that word these days, but it is…motivating? Encouraging? I don’t know. Though carefully and boldly done, Grapevine is not a pleasant movie. In fact, it’s harrowing. But I needed to see it because it’s proof that courage is real, and that people have it all the time. Through it all, there is Baldwin’s sensitive eye and queenly warmth, his easy but nervous smile, his voluminous silences and insistent, even overwrought, speeches. He hugs easily, befriends curious children, offers his subjects sympathy without asking them to lie to him or to themself. Many of them believe integration failed; none have rose-colored glasses about the incoming Reagan administration. In the face of all this, is the great author cynical? I do not know. I do not think so.

Starship Troopers (1997): Of his fascist space fantasy, Paul Verhoeven said: “All the way through I wanted the audience to be asking, ‘Are [the characters] crazy?’” It’s difficult for me to tap into the shock and horror America’s great Dutch portraitist sought to elicit: I don’t think the ultraviolent teen soldiers are “crazy” at all, even though I know they are. I’m not really sure why I’m not crazy in the same way, to be perfectly honest.

Foxy Brown (1974): My favorite fun fact about Pam Grier is that she came in second in a beauty contest in her hometown of Denver. Breathtakingly beautiful and almost studiously badass, Grier’s best-known contribution to blaxploitation is campier than Coffy (1973), her other big one, despite of course also being brutally, graphically violent. If you enjoy the genre, there’s a lot to love about this movie, but the script’s management of Foxy’s sexual assault, and her hilariously gruesome revenge, is one of my favorite elements. If you’re promising me rape revenge in your movie, then somebody better die—at bare fucking minimum!

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1I tried to read Beautiful World, Where Are You? and got bored.

2Some may attribute this to her Marxist politics, which others have questioned in light of her subject matter. I don’t really care either way because Rooney has been unambiguous about her support for Palestine and her condemnation of Israel, which is unfortunately not the majority position among a lot of these big-time authors.

3All the cool girls are reading it.

4A favorite film of mine now, and a favorite book of mine from childhood, in no small part because Clarke was one of the first authors to create a world in which homosexuality could be ethically neutral. Imagine that.

5Another Kubrick favorite.

6Who was not originally credited for her work.

November 13, 2024

A stupid question

A few hours before Folsom Street Fair began, Jade put some needles in my back and plugged each one with a miniature cork. I put on a hoodie—it was a chilly September morning in San Francisco—and we walked through the Tenderloin to SoMa, where the police barricades had gone up the night before. By 11 am, the clouds had faded. It was warm enough that I could comfortably stroll around in little more than a pair of Mr. S-branded neoprene shorts.

November 4, 2024

Who can say it?

Last month, the Arc of the United States—an organization that serves people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD)—published a blog post about the r-word. Alongside some questionable but well-intentioned editorializing, the post very briefly sketches the evolution of a 60s-era “neutral medical term” into a cruel yet ubiquitous epithet for people with IDD1. This evolution, the blog post acknowledges, encompasses the Arc itself: until 1992, the organization’s name was an acronym for “Association for Retarded Citizens.”

The timing of this blog post is not coincidental. While legally, clinically, and culturally we’ve begun to correcting for the harm caused by the pejoration of the r-word, it “stubbornly lingers in our vocabulary and even in some state laws,” as the Arc writes. With what feels like an “r-word resurgence” memeing its way across social and cultural media, “stubborn” is an understatement. (I have questions about this resurgence framing, but more on that later.) In any case, any reasonable person will agree that the r-word justifies and reinforces the dehumanization of people with IDD, which permits us as a society to physically and sexually abuse, financially exploit, deprive of resources, incarcerate, and kill them at much higher rates than people without IDD2.

Of course it does—that’s what slurs do! Scholar of dehumanization David Livingstone Smith talks about language as a precursor, if not a technology, of dehumanization that can predict more literal kinds of violence. “When you get that kind of rhetoric,” says Smith, referring to the Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant referring to Hamas/Palestinians3 as “human animals” and “monsters,” “you just know there will be terrible atrocities following from it.”

I won’t make the claim that the use of the r-slur by some random Twitch streamer or your asshole coworker is the same thing as official propaganda issued by the architects of genocide. I do mean to compare them, however, in order to get us thinking about the fungibility of language and physical violence. It’s for this reason, in fact, that I’ve (mostly) given up on lecturing people that I don’t have relationships with about using the r-word. They will stop using it when they see people with IDD as people, and this will not come about through lectures (which isn’t to say that social pressure—and social consequences—don’t have a role in supporting and enforcing social safety). In my experience, a non-disabled person willing to use the r-slur is already willing to do much worse to them, if they can get away with it. Something more robust is needed than a half-baked culture war.

The r-slur topic is what got me thinking about this new series4. I’m curious about the online discourse surrounding a slur that many of people it describes can’t participate in (!), as well as the collective decision among progressives to refer to r-slur users as “childish,” “immature,” or “trapped in middle school”5. I also intend to write about other points of entry into the topic, from “who can say it?” and reclamation; to the relationship between the slurred subject and the slur respecter; to the unsaid and unsayable simultaneously conjured and repressed by the slur’s signifier, signified, and anyone else in the room. And I think I can do it all without invoking Lord Voldemort.

Shemaa and her family are still fundraising to evacuate Gaza. Send me your receipt of donation of any amount and I’ll send you 1 free month of subscriber-only content.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1As are all slurs, one supposes.

2More often than not, people have more than one disability or more than one aspect of their identity serving as a pretext for this kind of dehumanization. This summer, after Mohammad Bhar, a 24-year-old Palestinian man with Down syndrome and autism, was mauled to death by an Israeli military dog, I did not want to say anything about it to anyone, on social media or real life, because I felt I could not do so without reinforcing the common perception of people with Down syndrome as sweet, childlike angels, a benevolent dehumanization has never been enough to protect them from far crueler kinds. What could I say about Mohammad that could not also be said about any other victim of Israel and its handler, the United States government—but may not be? Would those of us watching (I hesitate to say witnessing) the genocide of Palestinians from a few thousand miles away have accorded another young Muslim Palestinian man without IDD the same pity (I hesitate to say compassion)? Is receiving his horrific suffering with saccharine contempt any better than suspicion, or even apathy? In comparing Mohammad with non-disabled young Palestinian men who are branded as terrorist, we dehumanize all of them. For this I am so sorry. Fuck Israel and fuck America.

3I don’t conflate these categories myself, but the IDF definitely does whenever convenient.

4It’s one I’ve written about before.

5That’s so interesting, isn’t it? It feels like the next closest thing to calling them stupid; that is, to calling them the slur right back, which you can’t do—or can you?

October 28, 2024

David Davis

Body scan

Body scanMind: Head? Psyche? Or should I say brain, as I did for my last body scan? I never know which word to begin with when describing my mental state, which is really my emotional state, which is really my physical state. How can I possibly deconstruct the bodymind when the difference between here and eternity is a geriatric Manx for an alarm clock, followed by 15 minutes of light stretching and a cup of coffee?

As the dirty election approaches, the genocide bleeds on, and the world tracks for temperature rises of 2.6-3.1C this century1, all the little tricks I’ve learned from therapy, S/M, and surviving into my mid-thirties aren’t enough to settle me. Why should they? All signs point to very bad things in the very, very near future. But it’s almost disturbing to discover how much settling is still possible when my immediate physical needs are met (and at the moment, I’m very privileged to say that they are). (Oh yeah, I forgot about COVID. There’s that, too.)

Accountability time: I’m trying to write less about doom here on DAVID because I don’t think I add much, other than despair, to already-well-documented phenomena like climate collapse, fascism, disease, etc. I don’t think it’s useful, much less interesting—to me or to you, my beloved readers—to pop up every fortnight or so with yet more, I’m fretting, I’m panicking, and oh boy, am I ever scared! I wouldn’t say that I’m entirely at peace with the ways I’m which preparing myself for what’s to come2, but I do think this tendency undermines what it is that I am doing. I’m involved in North Brooklyn Mutual Aid3! I recently got a pen pal through the Prisoner Correspondence Project! I have made peace with death4! I’m looking into gun ownership! It also falsely inflates my sense of what agency I do have: there is actually very little that I can do in the face of all this, not least because nobody knows what’s going to happen. Even the information shaping my expectations is limited, colored, and biased against what I can know and learn from the internet which is, famously, designed to propagandize and feedback loop me into compliance or usefulness.

Over the past few weeks, I learned that Aruba has a lot of cactuses because it’s an arid xeric landscape5, saw a movie about what it’s like to attend boarding school in the Himalayan foothills, and finally gave up on a book about quantum electrodynamics (though not without coming to a half-understanding of the concept of action within physics). Just the other evening, Jade was served a TikTok showing how cargo ships stave off pirates while passing through the Guardafui Channel. I was suddenly overwhelmed. “The world is so big!” I exclaimed. On this planet, there is a functionally infinite number of lives (human and otherwise) I know nothing about, in locales as strange and foreign to me as Mars. My understanding of the world is minuscule, as is my life. This isn’t to say that its vastness, or the future’s unknowability, means nihilism is an option. But how it all shakes out isn’t just not my business—it’s beyond my capacity. Almost everything is, except what I owe the lives around me.

Sinuses: I don’t know if this happens to any of you, but once a quarter I wake up with an insistent congestion that is suddenly and volcanically resolved by me blowing my nose approximately 50-75 times. What emerges is healthfully clear but just as satisfying to expel as the hot, green morass that comes after debarking a plane at the tail end of a severe respiratory infection. Anyway, it just happened again the other week and it felt really good. I wish it would happen, like, every other day. More sustained than sneezing or cumming and much more pleasant than puking, it’s the kind of bodily function that really makes you feel like you’ve accomplished something.

Left thigh: My carving is healing really well, thanks so much for asking. After various needles and a caning from my boyfriend, I’m taking a brief tolerance break from pain that isn’t brought about my newest hobby: the rowing machine. If you’re doing S/M as a masochist type, I highly recommend it!

Shemaa and her family are still fundraising to evacuate Gaza. Send me your receipt of donation of any amount and I’ll send you 1 free month of subscriber-only content.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1The world’s biggest producers of greenhouse gases aren’t even on track for our best-case scenario’s worst-case scenarios—more on that here—and that’s not to speak of the impending collapse of the main ocean current system in the Atlantic, which would have devastating global implications and which is increasingly likely to happen (if it hasn’t already, there’s no way to be sure).

2What an ominous way to express the future.

3Speaking of mutual aid, revisited a cool piece about Aileen’s, a hospitality space for women in the sex trade, in Federal Way, Washington.

4If not aging or suffering lol.

5This island (you know how I am about my islands), located in the Lesser Antilles, is indeed desertlike, but that’s only partially due to its climate (which is changing, like everywhere else); Spanish colonization brought massive deforestation, drastically changing its landscape.

October 25, 2024

David Davis

It’s funny how sex passes through you. Gary Indiana—the huge bitch and faggot forefather who died yesterday—said that. Or rather, one of his characters did, in his novel Rent Boy (1993). I think I’ve overheard a million john life stories and another million whore life stories and once you plow off the bullshit the john’s story’s always “I’m lonely” and the whore’s story’s always “I came from a dysfunctional family,” its hustler hero complains. Rent Boy is about being desired, an inversion of another Indiana novel, Horse Crazy (1989), which is about the trials and tribulations of the poor bastard doing the desiring. If only these states of excruciation were mutually exclusive! But their author knew, even if his characters don’t, the truth: sex has a funny way of passing through all of us.

I have nothing to say that the elegies of social media haven’t said better, so I’ll leave you with a few humble recommendations for things to read and watch by and about the departed. Though I’ve only been reading Indiana for a few years now, I know, as all of us do, that something has been lost to us as artists, or New Yorkers, or Americans, or whatever. Thank god the work persists.

By Gary Indiana

“Fuck Israel,” (VICE, 2012)

“A Coupla White Faggots Sitting Around Talking” (short film, 1981)1

Some of his last published work: “Malaparte!” (The Ideas Letter, 2024) and “Five O’Clock Somewhere” (Granta, 2024)

About Gary Indiana

“A Vision of Neoliberalism in Flames,” by Christian Lorentzen

“Gary Indiana, The Art of Fiction No. 250,” interview by Tobi Haslett

“Gary Indiana Doesn’t Travel in Any Circles,” interview by Andrew Marzoni

“Sleep When I’m Dead,” by M.H. Miller2

Shemaa and her family are still fundraising to evacuate Gaza. Send me your receipt of donation of any amount and I’ll send you 1 free month of subscriber-only content.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Liz Purchell turned me on to this one.

2“You want to do what the artist wants, but you don’t want to go down in the books as the jellyfish killer.”

October 21, 2024

David Davis

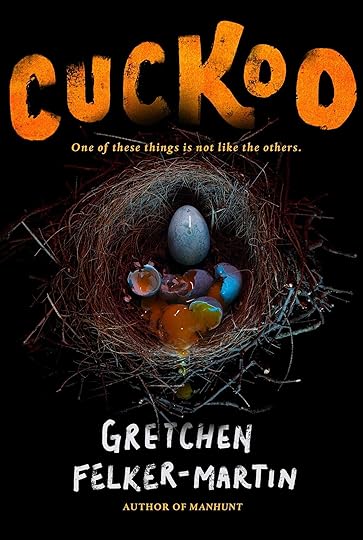

I used to publish articles and reviews in places other than DAVID, but I rarely do these days. As rates worsen, the time it takes to pitch, write, and revise for publication is too much—I simply can’t afford it. Which means that when I think a book or movie is worth writing about for someone other than myself, it must have really had an effect on me.

Unfortunately, I couldn’t find a home for my review of Gretchen Felker-Martin’s Cuckoo, but Natalie Adler at Lux Magazine made space for me to cover it within a piece about conversion therapy in new queer horror for their Fall/Winter issue. Now that it’s available in print, I wanted to share my original review of Cuckoo with you all, as both companion and endnote to the Lux piece, and as a paean to Gretchen, a writer I think the world of.

The first half of Cuckoo, the searing second novel by Gretchen Felker-Martin, is set in the mid-nineties. Sent away to be scared straight in a remote Utahn compound, the teen prisoners of Camp Resolution are coming of age in a country in which anti-sodomy laws haven’t yet been ruled unconstitutional, euphemisms like “reparative therapy” are still picking up steam, and nascent Trojan horses like “porn addiction” are waiting patiently for widespread internet use. These campers aren’t referred to as queer unless they’re being bashed (by a relative or camp counselor, take your pick), let alone as trans, the inchoate prefix-as-identifier that had yet to attract the opportunistic sex panic now taking the West by storm. Camp Resolution isn’t about “identity.” It takes high-schoolers captive for one reason only, as Pastor Eddie reminds Cuckoo’s protagonists after their first day of back-breaking labor and beatings: because their families are fucked up.

Which isn’t to say that these queer and trans teens are not also fucked up in the eyes of their captors, but for them, their sexual and gender deviance are symptomatic of a deeper problem. As Pastor Eddie explains, their parents don’t have the guts to guide them toward something better, to teach them how to be in the world. “The minute things got hard, they pushed you out of the nest and paid someone else to fix the problem,” he says. “They’re weak, and they abandoned you.” Had their families been better, is Pastor Eddie’s point, they wouldn’t currently be providing slave labor in total isolation from everyone they know, including the one or two relatives who might see their imprisonment for what it is.

Pastor Eddie’s irony is obvious to anyone who doesn’t hate children. It is true, if perversely, that Shelby, Nadine, Gabe (later Lara), Felix, John, Malcolm (later Mal), and Jo wouldn’t have been kidnapped and sent to the middle of nowhere if their families had been better. Though hailing from diverse backgrounds and family configurations, each camper shares in common home lives of tragic neglect and violent abuse. Like all conversion camps, Camp Resolution outsources that neglect and abuse for families that have realized, on some level, that they’re not equipped to dehumanize their children to the satisfaction of American heteronormativity. Along with the schools, clinics, and prisons, conversion camps—the bloody brick-and-mortars squatting down-funnel from sport and bathroom bans—are just the market meeting a demand.

Pastor Eddie’s speech will prove to be the gentlest example of the tough love that Cuckoo’s protagonists must endure until they return home at the end of the summer. But of course, none of them are supposed to. Not as themselves, anyway.

Like Manhunt, Felker-Martin’s first novel, Cuckoo brings to life a constellation of characters and their myriad backstories with rapid-fire dialog, breathtaking action, and tightly controlled revelation of plot. Obscenely graphic and terrifically feeling, Cuckoo maintains its focus at a relentless pace as Camp Resolution’s newest cohort susses each other out among gun-happy counselors and their belt-wielding apparatchiks. Segregated by birth assignment in their lodging and labor and surveilled within an inch of their lives, the campers are nevertheless able to recognize each other—sometimes even before recognizing themselves. Watching “the transsexual” Felix in the girl’s shower, Jo registers one of the fleeting attractions over which entire Twitter discourses are waged. “‘He’s kind of hot,’ she thought, wondering if that made her less or more of a lesbian.”

Felker-Martin toggles deftly between her many main and supporting characters, demonstrating with surgical precision the conflict between their senses of self and the “reality” being shoved down their throats. Even the dipshits still complaining about the needless complexity of they/them for a single person can follow along with the campers whose very bodies are at odds with white and cis supremacy; can empathize with the desires that are mostly undesired but, like all desires, inexorable. The morning after hooking up with John, Malcolm’s fatphobia shames his pleasure in hindsight: “In the light of day, he felt embarrassed by how eager he’d been. How much he’d liked it.” Though the campers’ backgrounds and responses to their capture—Should they tough it out? Fight back? Cooperate, like the prefect-style campers that enforce just as brutally as their counselors?—are unique and appropriately conflicted, not a detail about their personalities, pasts, and hopes for the future is wasted. Among the misgendering, deprivation, and broken bones, I found myself wondering how such significant suffering could be imposed upon characters so obviously beloved by their author.

From the campers’ memories of home to their bloody resistance against their captors, Cuckoo’s constant violence is a petri dish of power, an opportunity to observe its flow around and between identity categories that aren’t the explicit projects of the conversion camp’s bare life. As pretexts for their collective punishment, the campers’ queerness and transness serve to reinforce all modes of oppression: John’s fatness is integral to his father’s understanding of (and disgust in) his son’s effeminacy; Felix’s insistence on his maleness defies his immigrant father’s hopes for assimilation into American culture; Malcolm’s attraction to other boys, while not incidental to his abuse, is convenient cover for a mother who has turned her rage at her absent husband back on her children; Shelby’s girlhood is tolerated by one of her white adoptive mothers, but is seen by the other as a punishment, in the wet-dream register typical of gender-critical types (“The lit butt pressed to Shelby’s arm. The smell of burning flesh. You cannot do this to yourself, Andrew. You cannot do this to me.”). While they’re incapable of feigning the normalcy that would have allowed them to fly under the radar—as many of us would have, if only we could—not being straight isn’t really why they’re here at Camp Resolution. Their crime is having survived the physical, emotional, and sexual abuse their families decided that they deserved. Their queerness or transness makes destroying the evidence that much easier.

Which isn’t to say that Felker-Martin renders scapegoating as a uniform experience. Cuckoo balances a diverse cast of characters who must organize, despite their differences and disagreements, in order to save themselves. These teens aren’t at Camp Resolution because they are queer or trans. They are fags, dykes, and transsexuals, or perhaps some other slur, or perhaps nothing at all. The words both used and denied in order to degrade these children describe real power imbalances that cease to matter when the campers start to suspect that even if their counselors don’t kill them, something else will—something that slithers under the cabins and peers up at them through the floorboards. With her characters’ bitter jokes about concentration camps, environments designed to use identity for the sole purpose of its annihilation, Felker-Martin underscores the co-optability of liberal identity politics. Camp Resolution is no True Directions, the conversion camp from But I’m a Cheerleader (1999) whose earnest goal is to correct gender transgression and restore its campers to happy, healthy heterosexuality. Like other conversion camps, it promises rehabilitation it can never deliver; unlike other conversion camps, its harsh physical labor and arbitrary punishment conceal something even more sinister, something that’s causing campers to waste away, suffer blinding headaches, and begin sharing the same dreams, night after night.

Camp Resolution runs on queerphobia, but the monster at its heart is no metaphor. Its purpose unclear and its reach octopodean, the creature the campers call the Cuckoo is a massive, cervix-textured, foul-smelling alien lifeform that colonizes human bodies—“They’re going to take us. Our faces. Our lives,” is Jo’s horrified realization—then sends their replicas back to their unsuspecting families, hatchlings hungry for the faces (and then some) of the people that betrayed their hosts’ utter helplessness.

Able to convince families all over the country to hand over their own offspring, the Cuckoo grows, feeding on the queer and trans poster children of the American identity crisis that has gone on to take the lives of Nex Benedict and Alex “Boo” Taylor, to name two murdered youth from 2024 alone. That crisis is literalized by the Cuckoo as an extraterrestrial mother-parasite of Lovecraftian proportions from whom the imitations of human bodies protrude like tumors, mimicking the voices and words of the parents that gave the campers up. Their delayed realizations of their abandonment are among the most painful scenes in the book. “She sent me here to die,” thinks Gabe, shattered. “They both did.”

With Cuckoo, Felker-Martin forsakes euphemism to paint an exacting portrait of the campers whose lack of power begins with the wrongness of their bodies. In her extended descriptions of the Cuckoo’s unearthly incarnation, we see the same unflinching language reconstituted to convey its fleshy, weeping, even gynecological horror. Two different kinds of monster held up for our comparison—how could we fail to tell the difference? How could anyone?

With research showing a relationship between conversion therapy and suicidality, use of the term “survivor” for those who’ve undergone the former is hardly overstated—least of all in the case of the refugees of Camp Resolution. It’s nothing short of a hard-earned miracle that some (though not all) of our original campers make their hair-raising escape through the desert to the nearest town where, devastated by their ordeal and aware they can never return home with the story they have to tell, they begin their lives as runaways with the help of Jo’s grandfather. Though safe for the moment, their relief is hardly commensurate with their suffering; thanks to trauma, it never is. Shelby, Lara, Felix, John, Mal, and Jo may have made it out of Camp Resolution, but, like so many queer and trans adults, they must continue to live on inside of their memories.

In the 16 years between Parts 1 and 2 of Cuckoo, only Felix keeps tabs on the monster, following its cross-continental metastasization with the help of online forums and lonely stakeouts at suspected conversion camps, which as the nineties fade into the past have had to become more clandestine since his summer in Camp Resolution. His fellow survivors, now spread across the country in various stages of dysfunction and levels of contact, can deny or ignore it all they want. The Cuckoo knows time, and just about everything else, is on its side.

Like the Losers Club of Stephen King’s epic, IT, the campers are summoned by a self-appointed watcher to finish what they started going on two decades later—only their demon is even more formidable than Pennywise. Like the sewer clown plugged into ChatGPT, the Cuckoo iterates rather than replicates, absorbs rather than haunts, consuming entire families at a time and infiltrating the country’s most powerful institutions, its process reminiscent of the climate-driven model of Lyme-carrying ticks and toxic algae blooms. Only Felker-Martin could one-up King with the campers’ Hail Mary plan to take out the Cuckoo once and for all, the mechanism of which is one of her many winks to Cuckoo’s transsexual readers.

Cuckoo’s strongest connection to IT, however, lies in its author’s authentic sympathy for young people, one that I sensed when reading King as a child myself. Cuckoo is gory and disturbing, and even its quietest moments of connection are shadowed by tragedy. And yet I would recommend it to any young person, because it takes their vulnerability seriously. As this country’s organized assault on trans children proves, the liberation of all children is the next (final?) frontier of any radical politics, and Felker-Martin understands this better than most. Her dedication at the beginning of Cuckoo reads simply: For all unwanted children.

Shemaa and her family are still fundraising to evacuate Gaza. Send me your receipt of donation of any amount and I’ll send you 1 free month of subscriber-only content.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

October 16, 2024

David Davis: Members Only

Is it possible to do more with trauma than heal it? Referencing Avgi Saketopoulou in a about fascism and anti-trans sentiment, Willa Smart and Beckett Warzer expand on the psychoanalyst’s preferred subject, the traumatophiliac:

To make good use of one’s traumatic history means to “[enter] more deeply into its patterns of repetition,” rather than seeking to heal or eliminate trauma—a phobic response that leads to compulsive repetition rather than the possibility of transformation.

Has a phobic response to your trauma only made your distress worse? In attempting to dig the bullet from your flesh, have you instead pushed it deeper into your body?

October 11, 2024

David Davis

Over the past few years, I’ve stopped going to events with exclusionary gender policies, which has really simplified things. When it comes to events or spaces that make a point about being only for men or women, there’s little ambiguity; they’re closed to me as an androgynous transsexual, for better or for worse. Things start getting a little hairy, however, when the event or space attempts to use exclusion in order to be inclusive of people like me.

How many event flyers have you seen with gender policies that use language like: “for women and femmes,” “for women and non-men,” or “for everyone but cis men?” For all that they probably mean well, these efforts to define the event against those who can’t come—rather than as for those who are invited—make me much more uncomfortable than women’s locker rooms or cis gay circuit parties. Just as some people prefer to interact with certain genders (or their idea of certain genders), I prefer not to submit myself to the scrutiny of the (invariably) cissexual person who thinks a flyer with “women and trans only” isn’t ignorant and disrespectful1.

So where do I feel welcome? At events with expansive gender policies. Events with expansive gender policies may say they invite “all genders” or, are, like Bawdy, simply “a queer party.” They may advertise themselves as centering certain gender identities, such as women or dykes, but welcome all comers. Some, like Inferno, may acknowledge themselves as spaces where people who mostly identify a certain way come to cruise each other, while simultaneously making an effort to connect with attendees and organizers of more marginalized genders to make it more inclusive without losing what makes it special. While they can be imperfect, expansive gender policies do more to ensure that people with marginalized genders don’t have to work harder than anyone else to attend.

But isn’t “women and femmes” an effort, at least? Isn’t she/they’s heart in the right place? Wasn’t the original purpose of complicated door policies to make sure people with marginalized genders could come in the first place?

Sure. (And it’s here that I should point out that when deployed a certain way, “women and femmes” could very feasibly include me, a person who is never read as a woman or a femme in dyke spaces, while excluding a literal trans woman or trans femme. Or lbr, a fem/me cis guy!) But over the years and in my experience, that approach causes more problems than it resolves. If the language of a so-called inclusive event leaves trans people, especially women, wondering if they are truly welcome; if they will be scrutinized at the door; if they will be stared at, ignored, talked over, or degendered or sexualized against their will; if they will be presumed to be the aggressors in any conflict or abandoned if someone hurts or takes advantage of them, then what has it accomplished except further discrimination against trans people?

In my experience, the “women and femmes” lingo is often just window dressing, anyway. So no one too scarily masculine has made it past the velvet rope—now what2? What else are we doing to make sure that the dolls at our party are safe and respected and having a good time? Because I hate to break it to you, but cis women and people who can move through the world like them can be just as violent to trans people as cis men are. How often do Canva flyers with HR language advertise events that actually take tangible, material steps to make sure that trans people, women especially, are regarded as worthy of integration—and not just outsiders or tokens, useful for little more than virtue signaling?

I’m sorry if this is tedious. This gender policy thing isn’t an axe I grind very much, but I got to thinking about it again a few weeks ago when I went to Folsom for the first time in six years. I had fun, but the “no cis men” language among the dyke-adjacent leathersexuals in my vicinity was casual and frequent enough that I felt like I’d traveled back in time to my last visit, when “women and femmes” had more of a chokehold on dyke culture.

Folsom hosts countless groups, organizations, and meetups based on desire, identity, or affiliation, including the Playground, its formal space for “women of every kind and all trans and nonbinary folks.” While not for me, this language is pretty expansive3. And clearly I’m not alone, as it’s a popular destination among the, uh, non-cis men of Folsom. While many come and go, some stay there the entire time, protected from the sea of faggots and voyeurs and tourists surrounding them. I understand wanting to avoid cis men, but it does strike me as a choice to go out of one’s way—perhaps even flying across the country—to attend one of the nation’s premiere events of faggotry, one that began as resistance against the city of San Francisco’s shuttering of gay bathhouses at the dawn of the AIDS epidemic, only to make a lot of noise about escaping the cis male gaze (as if there’s only one) for the duration of your visit4.

Because listen, I’ve gotten into fights with cis men at Folsom. I’ve spent some time in public, where cis men famously are, and a fair number of them have a lot of feelings about me. But this effort to keep an entire gender out of gender-diverse spaces—not in order to create space for certain genders, but to circumscribe safe genders through the creation of unsafe genders—comes at the expense of trans people, especially those of us who are feminized, racialized, disabled, etc.5 It reminds me of means-testing for welfare benefits: efforts to weed out the people who don’t “need” or “deserve” food stamps will fail, with the bonus effect of also weeding out people who, according to your government’s totally unbiased standards, actually do “need” or “deserve” food stamps.

If your event is about celebrating, centering, or otherwise supporting trans people, just say that! Or if you want to do something without men around, that’s literally so fine. But the more convoluted gender exclusionary language gets, the more I feel like these events are more focused on hating the cis men who aren’t present than loving the people who are—and as a trans person, I can never help but wonder where that resentment is going to end up.

Not everyone agrees with me on this subject, and that’s okay. We can just go to different parties, which we do. But I’m tired of debating it with people who aren’t of the transsexual experience because their first argument is always this one: Well, I don’t want cis men at this event because I have been harmed by them before.

Over the years, it’s gotten more difficult to take this argument for what it is: the divulging of a very personal, sometimes very traumatizing experience of gendered violence. This is emotional and vulnerable, and for my two cents, gendered violence is a sound reason to find value in the exclusionary gender policy, at least initially. But I have to make an effort to keep all that in mind because it has begun to feel like an accusation in and of itself. Does this person think I haven’t considered that men as a group are incentivized to use their power over and against us? I wonder. That I can’t understand or relate to their fears? That I don’t come to this issue with similar experiences? That I haven’t also been assaulted by cis men, of all orientations, in gay and straight spaces alike? It’s difficult not to feel it as transphobia6, which in my case encreatures me as both a man, in that I can’t relate to women’s experiences, as well as a woman, in that my experiences don’t matter (I’m the woman’s woman). I can’t be trusted, as if I were a man, yet I don’t have the power over a woman that a man does. I’ve been assaulted by cis women, too—why is it that gender-diverse spaces have to accommodate someone like me, but not the cis women who’ve taken advantage of our gendered power differential?

Personally, I actually manage a lot more hostility toward cis women than cis men because I’ve never expected loyalty from the latter—but that’s my trauma and my neurosis, and I can’t build trust and connection with that (you can read more of my thoughts on community here). We don’t know what a stranger will do when they enter our space, and to pretend that their gender can help us predict that isn’t just absurd, but counterproductive. We can only agree on which behaviors are unacceptable and remove those who behave unacceptably.

Shemaa and her family are still fundraising to evacuate Gaza. Send me your receipt of donation of any amount and I’ll send you 1 free month of subscriber-only content.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1“Women and trans” what, exactly? Do the people throwing these parties recognize that they sound like alt-right Facebook paid ads and no-pic Grindr accounts that say “passable trans only” in the bio? “Women and trans”—as if these things were mutually exclusive.

2Or maybe they have, but they’re on notice.

3Although I heard that blood and fucking wasn’t allowed there this year…!?

4As if faggotry were only for cis men.

5As hordes of cis men are besieging the ramparts of dyke night—do you hear yourselves?

6The kind shaped by my other identities, such as being white, being straight-size, being TME, etc.

October 7, 2024

David Davis

I woke up in an ugly mood because it’s October 7, 2024, and because I’m disturbed by the climate-driven changes in my local weather patterns, and because I’m likely dropping from a scarification I had done on Saturday. I want to write about what’s upcoming for this newsletter—you know, gin up some anticipation for all 4,336 of you—but how can I, with all this1?

Well, I can, and so I do, I suppose. I won’t attempt to pass off what I do here as more than it is, but what it is may be of use to some of you, if not as edification then at least as distraction. It’s both for me. So, what’s upcoming:

FreeUpcoming topics include: gender policies at play and sex parties; supermasochist Bob Flanagan; art patronage; reviews of sadomasochist art; and another body scan, which has become a series of sorts.

New series alert! I’ve been wanting to write about slurs for a long time now. From who can reclaim what, to the so-called resurgence of the r-word, to the humbling consented to by those who refuse to use a slur that does not apply to them, there’s a lot to think about here, especially regarding the unsaid.

PaidCuts like a knife: Over the summer and now into fall, I’ve been having some really interesting sharps experiences. For those who’d like to see photos and read about the process, I recommend subscribing ASAP. It’s $6/month, but only $5/month if you pay for the year in advance. The majority of DAVID is always going to be free, so don’t sweat it if I’m not in your budget. There are much more important things.

Shemaa and her family are still fundraising to evacuate Gaza. Send me your receipt of donation of any amount and I’ll send you 1 free month of subscriber-only content.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1My sibling lives in the Midwest but regularly visits their partner in Florida, so they’re one of my on-the-ground contacts for climate collapse as it unfolds in those parts of the country. Today, they only just made it out of the Sunshine State ahead of Milton, which is due to hit on Wednesday and will likely be a Category 4, if not worse. Ever since 2018, when the Camp Fire—California’s deadliest wildfire—took out the town down the road from ours, the future has become our most consistent topic of conversation. While my sibling and I tend to catastrophize, there is little to indicate that our pessimism is unrealistic. If something doesn’t change, we’re scheduled to soar past the 2015 Paris Accord’s agreed-upon goal of keeping the rise in global surface temperature below 2 °C (3.6 °F) above pre-industrial levels, conditions which exacerbate and are accelerated by the immiseration of the world order, from the climate refugees of Hurricane Helene wading through toxic mud to the 25 million Sudanese suffering from “severe hunger” to the likely hundreds of thousands of Palestinians who have been murdered over the course of the genocide that began a year ago today.

October 3, 2024

David Davis

“It is often our mightiest projects that most obviously betray our degree of insecurity,” explains Austerlitz, the protagonist of W.G. Sebald’s novel of the same name.

To wit: in Europe, the star-shaped fortresses of the 18th century were built in anticipation of advancing armies, only to undermine their effect by accentuating their weak points and expanding to keep pace with new enemies, urban sprawl, and the disadvantages of their mobile opposition. “The largest fortifications will naturally attract the largest enemy forces,” Austerlitz reasons. “The more you entrench yourself the more you must remain on the defensive.”

For all their brilliance, he says, the continental masters of military architecture never seemed to cotton on to the fundamental “wrong-headedness” of their behemoths. Instead, they “forged ahead…far and beyond any reasonable bounds.” Austerlitz muses that smaller buildings—like cottages and bothies—offer at least a semblance of peace to their beholder, but what of siegecraft’s vast and terrible edifice? He leaves us with this banger:

At the most we gaze at it in wonder, a kind of wonder which in itself is a form of dawning horror, for somehow we know by instinct that outsize buildings cast the shadow of their own destruction before them, and are designed form the first with an eye to their later existence as ruins.

It’s all too easy to compare Austerlitz’s fortresses and their inexorable growth with the cancer of capitalism. As they expand, militarizing every square inch of a territory along the way, they become the borders they ostensibly defend, increasing their mutual hardness, sharpness, and destructive capacity as they fluctuate and contort within and around each other.

This is as true now in the States as it was in Belgium a few hundred years ago: nearly 2 out of 3 of people living in America are within the 100-mile border zone in which USCIS, ICE, and US Customs and Border Protection are granted certain “powers without warrant” (the Fourth Amendment still affords citizens some protection from that, sort of). In his review of John Washington’s The Case for Open Borders, Jake Romm calls borders “hellgates”—but which side is hell on? The Harris presidential campaign, and the Democratic establishment it represents, has agreed with the Republicans that it’s on the other side; as Republicans radicalize on immigration, writes Daniel Denvir, the “Democratic elites chase after them.” In contradiction to their Trump-era lip service, the Democrats’ “‘normal’ position on immigration moves ever rightward.”

But you and I know, of course, that the need to keep “them” out is propaganda designed to conceal the diminishing returns of citizenship here in the imperial core. The chickens have always roosted, but those birds are really going for it in 2024. As Romm writes, “The preservation of borders in the face of climate catastrophe, global conflict, and regular economic crises will require ever greater internal and external violence.” Beyond America’s borders, famine has been declared in Darfur, melting glaciers have forced Italy and Switzerland to redraw their borders, and greenhouse emissions from Israel’s genocide (now spilling over, again, into Lebanon) rivals those of dozens of other country’s annual outputs combined; within them, we beg our government to save us from tropical storms, chemical spills, and pandemics, and its response is to send yet more money to murder Palestinians.

Is our border a fortress? If these are still separate entities, what’s to stop their eventual convergence? Or has it already happened?

Fundraisers for survivors of Hurricane Helene are here. Send me your receipt of donation and I’ll send you 1 free month of subscriber-only content.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 55 followers