Davey Davis's Blog, page 4

April 17, 2025

The eyes have it

I never slept well as a kid, always certain that something—a vampire, the devil, germs—was under my bed or outside my window. I’m not so old that an adult would have gotten the Sandman on my case, but I knew who he was thanks to the Chordettes’ “Mr. Sandman,” the 1950s pop song that briefly features the apparition himself (…Yes…?). By the 90s, the retro hit had acquired several layers of irony on top of its intended cuteness, meaning I was just as likely to hear it at the grocery store as I was in a horror movie like Halloween II (1981)1.

Like all folkloric monsters, the Sandman, a creature of Germanic and Scandinavian fairytale, was at one time more straightforwardly disturbing. After centuries of giving kids the willies, his entrée into text was with E. T. A. Hoffmann’s 1816 short story, Der Sandmann, as a “wicked man” who steals the eyes of children who won’t go to bed. The story is told by a character named Nathaniel, who as a child believed that his father was in thrall to the Sandman himself. As an adult, he has a memory of the Sandman threatening to take his eyes while his father begs for mercy on his behalf.

In Carol J. Clover’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, she distills the “eye of horror” down to the organ itself as penetrator as well as site of penetration: the eye is both a weapon and a “natural and original vulnerability.” Here she quotes Freud’s writing on Der Sandmann:

“We know from psycho-analytic experience . . . that the fear of damaging or losing one’s eyes is a terrible one in children. Many adults retain their apprehensiveness in this respect, and no physical injury is so much dreaded by them as an injury to the eye . . . A study of dreams, phantasies and myths has taught us that anxiety about one’s eyes, the fear of going blind, is often enough a substitute for the dread of being castrated.”

I don’t remember worrying about my eyes in my childhood, but since developing panic attacks about two years ago, every other month I convince myself that I’m suffering the initial symptoms of an infection or disease that will permanently rob me of my vision. Last week, when the psychosomatics actually took shape in what was eventually determined to be a garden variety stye2, it was only years of practice, patient reassurance from my lovers, and my alprazolam prescription that kept me from becoming completely hysterical.

At the beginning of HRT, I began to experience a reversal of time more dynamic than mere regression. Fumbling my way through puberty3, I found myself brushing up against neuroses I had relegated to my twenties, teens, even my childhood. I kept aging, of course, but it was as if my path into the future was now doubling back through long-forgotten developmental milestones and the defense mechanisms that sprouted like flowers around them. Maybe these flowers grew from bulbs, which when peeled would reveal more bulbs inside, each enshrining its own abyssal bloom. Where to begin, in such a situation? Where to end?

For decades, I avoided my transness with dissociation. When I finally permitted my body to know this truth about myself (by this I mean the surgeries and the medicine, but also the acknowledging and accepting and entrusting of this truth with others), I gradually gained the ability to move both forward and backward in time—to remember my past rather than reside in it; to wonder about my future rather than merely anticipate or ignore it. (I don’t think the power of time reversal is unique to transsexuals. It can happen to anyone who begins to really feel their neuroses, which is the first step to really thinking about them4.)

Six or so years later, this freedom of time has granted me the capacity to regard my neuroses with some curiosity. Does my new fear of blindness resemble any other fears that I’ve had before? When and where did they come up? If it was during my youth or childhood, which adults were involved, and how? If these associated fears did resolve, what story did I tell myself to explain this resolution? Did it happen in the way that I had feared or hoped? With these questions, I pluck the neuroses from their respective places in time and lay them out next to each other for comparison, like budding flowers, like pages of text: how does today’s narrative inform yesterday’s, and vice versa?

With the help of this system, I’ve realized that my so-called fear of blindness is actually about something else (no shit!). When obsessing over what’s going to happen to me, I don’t really dwell on my prospective life as a newly blind person and the struggles that would entail, like learning how to walk or read in an entirely new way. Instead, I focus on the possibility of being informed (perhaps obviously but nonetheless crucially by a white-coated authority figure) that my eye, as I have known it my whole life, is done for. Over. Caput. It’s not its injury or uncertain future that terrifies me, but the moment of sickening revelation that these entail, a cliffhanging sensation that I associate with other kinds of dreadful anticipation, like wondering if I will pass in a bathroom or at work. My eye, my “natural and original vulnerability,” as Clover writes, leaves me open to those who may diagnose, clock, or revile me using their own eyes—more reasonable fears, certainly, than a sudden and random loss of sight.

A symptom of the trauma of becoming, Freud’s castration anxiety—a universal experience that takes place between the ages of 3 and 5—is associated with the fear of losing control, autonomy, and even life itself. If we put aside the idea that HRT marked the beginning of my adolescence and instead regard it as my birth, two years ago I would have been right on track for this psychosexual development.

Years ago, I started going to therapy because I wanted answers. In the last year or two, I’ve become interested in psychoanalysis because it refuses them altogether (“All analyses end badly,” as Janet Malcolm wrote). Anyone with an irrational, or even hysterical, fear knows that recognizing it as such usually isn’t very helpful. But there is something soothing, even encouraging, about seeing my fear for what it is: an expression of a mechanism that is deeply, inevitably human.

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Get a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content when you screenshot your donation of any amount to political prisoner Ángel, a butch lesbian, community organizer, and 2020 uprising defendant who is currently in ICE custody. She will not fight her deportation to Chile, where she has not lived since the age of 7, but will need money to rebuild hir life from scratch. You can also send money directly to Loba-Cabrona on Venmo or $PunkWolfe2 on Cashapp.

1As horror filmmakers well know, pop music deracinated from its context by time or juxtaposition can go from catchy to creepy really fast. Just as pop music gains a sinister new register over time, more “serious” music loses it, as Metallica’s “Enter Sandman” demonstrates.

2My first and, god willing, my last.

3Widely regarded as my second, which I’m not sure I agree with. The longer I’m at this, the more I feel that being forced to undergo the wrong puberty kept me locked in childhood. The TERF logics that infantilize white transmasculine people sure tell on themselves, don’t they?

4Consideration being qualitatively distinct from anxiety’s spectrum of anticipatory affect: fretting, stewing, perseverating, fixating, etc.

April 8, 2025

What I've been reading and watching

What I’ve been reading

What I’ve been readingApril has been busy, so this time I’m cheating with an audiobook: CHAOS: Charles Manson, the CIA, and the Secret History of the Sixties by Tom O’Neill.

To really enjoy CHAOS, you have to be kind of a Manson nerd (I’m not, but his story lives at the intersection of New Hollywood, the civil rights movement, and the libidinal energies underpinning twentieth/twenty-first century true crime, topics about which you could say I’m passionate). Yet you must also be credulous enough to need persuading that there may be something…untoward…about the institutions (child prisons, policing, the CIA, etc.) that produced the world’s most famous Beach Boys stan. While I appreciate O’Neill’s contributions to the case that the United States government is so corrupted by racial capitalism that it would manipulate charismatic psychopaths into destabilizing the Black liberation movement and dispatching inconvenient political figures, I certainly don’t need it, you know?

More interesting to me, as a writer, is how CHAOS illustrates the deterioration of American journalism over the past 25 years. What began in 1999 as a three-month assignment by a now-defunct entertainment magazine snowballed into twenty years of obsessive research that put O’Neill hundreds of thousands of dollars in debt with, if not little to show for it, then at least not the definitive proof of the CIA’s role in the Tate–LaBianca murders that he was looking for. This is not to undermine O’Neill’s persistence, resourcefulness, and grit; the man deserves a Pulitzer for all the death threats he received in the making of this book alone. For all that it’s inconclusive, CHAOS is not a failure, but it does represent an increasingly unimaginable undertaking. Unfortunately, in 2025, the notion of an independent investigative journalist devoting a quarter of his life to learning the truth behind one of the most famous crimes of the past century without institutional support other than a few book advances is almost as unthinkable as the nightmarish evening of August 9, 1969.

For a significantly shorter exploration of this same topic, I recommend Alexander Sorondo’s new long-form piece on William T. Vollmann. “The Last Contract” documents the writer’s herculean efforts to publish A Table for Fortune, his 3,000-page novel about the CIA. Not even Vollmann, the man for whom every avenue of inquiry—from poverty, to climate change, to violence—becomes a white whale of sorts, can escape the collapse of publishing, media, and journalism as we know them. I suppose I’m part of the problem: I’ve read lots about Vollmann, and a few short pieces by him, but have yet to finish one of his books.

What I’ve been watchingMaurice (1987): Last week, Jade and I went to the Paris Theater (once informally known as the Merchant Ivory theater) for a screening of Maurice, which debuted there in 1987. By a stroke of luck, its director and co-writer, James Ivory, was sitting directly in front of us, accompanied by a strapping young man that Jade described as one of the top-ten most beautiful people she’d ever seen. I would go to war for him, she whispered as we tried to make ourselves comfortable in the tiny seats. Looking younger than his almost 97 years (although, Jade wondered, when was the last time she’d been this close to someone so old?), Ivory was dressed in a charming red knit sweater and khakis, a polished wooden cane propped against his knees. Alert but distant, he seemed nonplussed when director Ira Sachs (who we also adore) came to shake his hand. The man of the hour, said Sachs. Indeed, Ivory’s silence suggested.

It wasn’t difficult to focus on the movie, which is one of my favorites1, but every so often I glanced over at Ivory, whose three-quarter profile shone like a quail egg at my nine o’clock. He watched the screen carefully, his expression rarely changing, except when Ben Kingsley’s hypnotist adenoidally observes that, “England has always been disinclined to accept human nature.” Like the rest of the audience, he laughed. It’s a great line read in a movie chock-full of them.

After the show, Ivory took to the stage to be interrogated by Sachs. I say interrogated because he resisted almost every question with generalities, quibbles, or circuitous summarizing. Of course homophobia was different in 1912 than in 1985! Of course his partner of 40 years, Ismail Merchant, and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, shaped his world! He seemed a trifle over it; but maybe he was just distrustful, humble, or hard of hearing. When asked about Hugh Grant, the Maurice co-star who went on to become the king of the ‘90s romcom (and of my heart 🫶), he said simply that he had gone out for Daniel Day-Lewis’ role in A Room with a View (1985), but that he hadn’t been quite right.

Sachs was a good sport. Maurice, he explained, had meant so much to him as a young gay man who struggled with the closet as the film’s main characters do, despite having been born 70 years later in a different country. While Ivory wasn’t dismissive outright, he didn’t seem particularly interested in getting into it all, either. Perhaps when you’re almost 100, you’re just zen about everything. When, prompted by Sachs, Ivory announced his age, I was surprised by how excited I felt, by how hard I clapped along with the rest of the audience.

Ivory did say a few memorable things, including the observation that actors are deep, while directors are shallow, plus a few kittenish remarks that set the audience laughing. Still, I have to admit I was disappointed that he avoided answering the question that was, incidentally, one I asked Jade as the credits rolled: why had he chosen to end Maurice on Grant’s tragic Clive closing the windows on the greenwood, and not with the book’s happy ending (which had prevented its publication until many years after its author’s death)? In response, Ivory focused instead on the beauty of Clive’s wife in her looking glass, her face placid and yet fixed, as if she is doing a difficult math equation in her head. Of course, Ivory said, she didn’t know what was really going on, and [her closeted husband] would never tell her. But in a scene just a few minutes before, Clive remarks that his wife has an uncanny intuition. Like the other mothers, daughters, and wives in Maurice, her feminine repressions play differently than those of their male counterparts, but rarely are they as ignorant as they’re meant to be perceived. It’s funny—every time I watch Maurice, I’m struck anew by its women characters, who for me all but disappear between screenings. I wonder what this says about me.

“Fun City: NYC Woos Hollywood, Flirts with Disaster”: Criterion’s April programming of ‘60s and ‘70s cinema set in New York depicts a “raw and often surreal portrait of a city in crisis.” Popular classics—like Rosemary’s Baby (1968) and Dog Day Afternoon (1975)—adjoin gritty gems that were new (to me), like Little Murders (1971), the scariest comedy I’ve ever seen starring the adorable Elliott Gould and a scene-stealing Donald Sutherland, and Black Caesar (1973), helmed by the sartorially sensational Fred Williamson as a Harlem mafioso with a diehard vendetta. It includes Black Caesar’s original ending, the fitting yet surprisingly surreal conclusion to a very violent film that has you simultaneously rooting for and despising its underdog.

Opus (2025): Not even Ayo Edebiri, whose beauty is just “normal” enough that she can be reasonably cast as the world’s most charming working girl, could make this AI movie likeable. Its villain (John Malkovich) is Alfred Moretti, a megalomaniac pop star with a murderous, if ideologically muddled, cult following that claims to worship creativity. Edebiri is a no-name young journalist who tries to foil, then capitalize on, his diabolical plans to spread his religion across the country. I say that Opus is an AI movie as both compliment and insult: while it seems interested in examining the contemporary hostility toward human creativity—what is its value? why does it matter? does it have a future?—it does so with a derivativeness that isn’t even redeemed by iteration. Whether or not we’re intended to find something salvageable in the dogmatic goulash that is Moretti’s ethos, the end result is the same: a film about art and creativity characterized by bad writing, wooden acting, stupid plotting, and pointless cinematography (establishing panoramic shots seem to take place in a different movie altogether, and one gets the impression that writer and director Mark Anthony Green has some kind of grudge against good lighting). There are a handful of pretty/interesting/frightening images and a fascinatingly disturbing nonsequitur of a puppet show about Billie Holiday, but otherwise this one’s poop from a butt.

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Get a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content when you screenshot your donation of any amount to political prisoner Ángel, a butch lesbian, community organizer, and 2020 uprising defendant who is currently in ICE custody. She will not fight her deportation to Chile, where she has not lived since the age of 7, but will need money to rebuild hir life from scratch. You can also send money directly to Loba-Cabrona on Venmo or $PunkWolfe2 on Cashapp.

1I’ve written about it here, but if you’ve only got a few minutes today, skip it for Alex Chee’s wonderful “The Afterlives of E.M. Forster.”

March 31, 2025

Body scan

Hair: Sometimes the difference between a good gendering (Sir) and a bad gendering (Here you go, um, I wanna say…shim?) is a haircut. My barber is a very friendly queer-identified cis man in an open marriage with a cis woman who would just love to fuck me, so he delights in giving me my monthly gender-affirming trim while oversharing about his sex life. To be clear, I like him. Like any good barber, he’s got the gift of gab

March 27, 2025

You can now preorder "Casanova 20"

🎀🎀🎀My third novel, Casanova 20: Or, Hot World, is now available for preorder 🎀 🎀🎀

I’m so grateful to the Catapult team, my peerless editor, Alicia Kroell, and all of you who support me by subscribing, sharing, purchasing, and even talking shit, which is still attention. More to come!

Thank you for reading and sharing my newsletter. Buy my books or find me on Twitter, Instagram, and Bluesky.

Get a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content when you screenshot your donation to any amount to political prisoner Marius Mason, who is currently serving 22 years in federal prison for acts of property damage carried out in defense of the planet. A trans man, Mason won the right to be transferred to a men’s prison but was recently returned to a women’s facility following a Trump executive order.

March 25, 2025

Who's afraid of writing sex?

Almost every time I do a reading, someone—sometimes the host, often an audience member—asks about writing sex: how exactly does one do it without being {TIGHT SHOT OF RAPID PUPIL CONTRACTION} cringe?1

Because of what I write about and what I am (namely, trans), even my non-sex writing is identified with sex and sexuality, so admittedly the interests of my audience skew along those lines. But it does seem that the fear of writing sex badly is a common one—from 1993 through 2022, the Literary Review had an annual award for it2—especially for writers who are young and unpublished. I’ve doled out my fair share of practical advice, but always with reservations I could never quite put into words. It’s not that I worried about being wrong; I’m no expert, but there are so many ways to approach this challenge, one shaped by endless anxieties and constraints, that I wonder if this is even possible.

Maybe that is what’s been bothering me. Why are so many writers afraid of writing sex in the first place?

A quick search turns up a survey of writers and filmmakers with recommendations for writing sex the non-humiliating way, most of it as sound (probably) as it is contradictory. The following, mostly sourced from interviews and essays, are just a small sample of how-tos, courses, and internet listicles that go on for pages:

Focus on emotions—not physicality.

Ask yourself, does it drive the plot?

Try storyboarding (just don’t forget your intimacy coordinator).

Listen, there’s nothing wrong with improving your craft. But don’t the stakes seem a little high for this particular facet of it? This fear of writing sex that’s too cheesy, tawdry, corny, or horny is so oppressive that people will fret and fuss and even fork over their hard-earned cash to get it right. How much sense does this make in 2025? Does writing sex well matter when everyone is beautiful and no one is horny and audiences (especially younger ones) want to see less sex3? Does it pay to master sex for a literary audience when “novelist” is less of a job than ever; when not even white male writers can get a word in edgewise; when such work that you do manage to publish is plagiarized by AI, the same technology that’s toasting the planet and stealing your day job; when the institutions that fund and recognize writers are in bed with genocidaires; when your best bet for making money is engagement, not expertise? From a career perspective, anyway, shouldn’t becoming “good” at writing sex rank pretty low on the writer’s hierarchy of needs?

“I don’t think of sex as any more difficult to write about than any other human behavior.” That’s Rachel Kushner, and I agree with her—to a point. Were our culture sex neutral, writing sex wouldn’t be any more difficult than writing about two people playing a game of chess. But if we’re afraid of talking about it honestly, let alone doing it, it follows that writing it can be just as fearful a prospect, if not more so. Because in this context, writing “bad” sex isn’t just a technical shortcoming. To fuck up a depiction of an act that we fetishize, at turns, as immoral yet sacred, unspeakable yet inescapable, unique yet uniform, as decadent and dirty and immoral, becomes a personal failing. We’re overidentified with and implicated by sex to the point that it can never be fictional, even in fiction. Any art worth its salt exposes the artist, but if this exposure doesn’t land, it’s an indictment of the most personal sort: if you’re unable to represent sex, this most common and animal and degraded of activities, one that everyone wants and does in the same and right way (or else!), not only have you demonstrated some level of inhumanity, but you’ve revealed yourself as a person to be too cheesy, tawdry, corny, or horny—that is, too literal, too earnest, or even on the wrong side of obscene4.

Unlike a game of chess, sex adjoins obscenity so closely that writing it poses emotional and even professional risks to the author that the former doesn’t. Perhaps on some level it serves us to confuse these risks with technical difficulty. We’d rather believe that there’s a method, a class, or a hack for sex writing, rather than admit that doing it publicly makes us vulnerable to others and to ourselves.

You know what’s interesting? People ask me about writing sex in fiction even though it’s something I’ve done very little of. My characters have sexual fantasies, engage in sadomasochism, experience sexual assault, and dissociate their way out of and around consensual intercourse—but sex qua sex, and the activities it conventionally entails, rarely make it into one of my books. Even my sex writing here on DAVID is pretty oblique. I have a strong sense of privacy, though not about the things that most people are private about. Although it may not seem like it, there’s a lot that you will never see.

I haven’t written a lot of sex, but I have identified myself with it publicly and repeatedly, not just as a writer interested in sexuality, but as an out transsexual. I think this is what people who want my advice about writing sex are picking up on: that I’m living the worst-case scenario of a writer who is fearful of sexual exposure. This is something I’m proud of because I’ve sacrificed for it, this honesty, which has affected my relationship with my natal family, my career, and my safety in the world. I’m not fearless—far from it—and I won’t escape without, at the very least, the public humiliation of taking artistic risks only to strike out, which has happened too many times to count. But I am doing what many of these people are afraid is impossible for them, and that’s what they’re curious about, even if they don’t quite realize it.

Unfortunately, when it comes to writing sex, the only advice I have to offer is the worst kind someone can give: you just have to do it.

New fundraising request: Get a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content when you screenshot your donation to any amount to political prisoner Marius Mason, who is currently serving 22 years in federal prison for acts of property damage carried out in defense of the planet. A trans man, Mason won the right to be transferred to a men’s prison but was recently returned to a women’s facility following a Trump executive order.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1I’m not a big deal, so such events are few and far between. With my new book coming out later this year, however, more are definitely in the works 💃

2Notable winners include Normal Mailer and Morrissey, with John Updike meriting one for Lifetime Achievement.

3The erotic thriller has been eulogized almost to death, but Karina Longworth’s podcast series on the subject is great stuff.

4But isn’t this all of us? I recently started Carol J. Clover’s Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film, which explores the relationship of the young male viewer to the female victim-heroes of the slashers of the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. In her psychoanalytic reading, a horror film, like a dream, can be peopled with simultaneous variations of ourselves. “Competing figures…resonate with competing parts of the viewer’s psyche (masochistic victim and sadistic monster, for example)…the force of the experience, in horror, comes from ‘knowing’ both sides of the story.” As viewers confronted with fears “imaginable…only in nightmare” and fantasies we can’t admit to, even to ourselves, we manage our myriad repressions by identifying with characters across genders and “types,” an experience of forced de/feminization (though she doesn’t use this term) by the director. As Clover writes, “Hitchcock’s ‘torture the women’ then means, simply, torture the audience.”

March 16, 2025

What I've been reading and watching

What I’ve been watching

What I’ve been watching I recently stumbled across Let There Be Light, the 1946 documentary directed by John Huston. Narrated by his father, actor/patriarch Walter Huston, Light follows a cohort of young veterans receiving in-patient treatment for PTSD, referred to as “nervousness” and “psychoneurosis.” While it was produced to educate the public about the mental health effects of war, the government ended up suppressing this unexpectedly life-affirming little movie until 1981 for fear of its effect on recruitment. Perhaps this is why Light, as Kent Jones writes for Reverse Shot, is a specimen of failed propaganda: everything that made Huston an artist, “his instincts, his extraordinary sensitivity, his way of honing in on the issue at hand like a water witch with a divining rod,” ultimately undermines the military agenda. Indeed, all of the films he directed for the Army Signal Corps—despite being considered among the finest made about World War II—were either unreleased, censored, or banned outright.

I don’t think I need to go into the hypocrisies and contradictions of mental healthcare provided to grease the meatgrinder, so I’ll stick with my aesthetic impressions1 . I adore American narrative films from this decade for many reasons, chief among them the way people speak. You see these tendencies in Light, all the more enchanting because they’re unscripted: the use of the interjectory Why at the beginning of a sentence; words and expressions like sweetheart, fella, photograph, That’s a boy, Take it easy, and at all pronounced as a’ tall; stronger, sharper regional and ethnic accents, some of them eliciting Looney Tunes lampoons of film noir icons like Humphrey Bogart and Edward G. Robinson. Because their doctors are at work on their unconscious, the documentary’s subjects, a diverse group of traumatized vets living together in an (integrated!) institution, are given the freedom to express themselves in uncertain, abstract, and emotional terms, leading to moments of poetry, as when a soldier talks about a pleasant dream he had of his family sitting around the dinner table “admiring each other.”2

That some kind of review board could see Light’s examples of psychological healing as a threat to American military interests is tragic, but not unfounded. Followed to its logical conclusion, any modality that (mostly) regards its patients as people will go on to undermine the violence upon which these institutions rely. The fact that Light exists today feels something like a miracle.

Vanishing Point (1971) has been on my to-watch list since Death Proof (2007), one of the only Tarantino films I consider salvageable. I was pleased to find that age has not diminished the excitement of Richard C. Sarafian’s Odyssean cross-country speed bender (whose muddled politics are revealing, if nothing else). Think Easy Rider (1969) meets The Warriors (1979) in a white Dodge Challenger. I’d love for someone to program a film series around omniscient-seeming disc-jockeys and/or diegetic radio: The Warriors, Do the Right Thing (1989), Groundhog Day (1993), Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)…

There is sincerely no need for anyone to watch Am I Ok? (2022), Tig Notaro and Stephanie Allynne’s sleepy straight-centric lesbian awakening com/dram, but I will never deny that Dakota Johnson has an ineffable charisma. Her placidity should be boring, and yet—! I imagine that being raised by Melanie Griffith and Antonio Banderas is a very dramatic situation, possibly involving partying and colorful scarves, which might cultivate an unusual groundedness (or depression, which it seems that the low-affect Johnson has struggled with) in a certain kind of child. At any rate, she’s one of my favorite nepo babies.

In Stahl’s beautifully saturated Leave Her to Heaven (1945), Cornel Wilde is merely cute. In the black-and-white Shockproof (1949), a lesser Douglas Sirk, he’s actually pretty sexy as Griff Marat, a true-blue parole officer who falls in love with the blonde (Patricia Knight) he’s trying to save from recidivism. Forgettable movie, but he does take his shirt off a few times.

What I’ve been readingHerculine by Grace Byron: A twenty-something conversion therapy survivor flees New York City for her ex-lover’s trans-girl commune—an Island of Misfit Dolls in the heart of rural Indiana. Named after Herculine Barbin, a nineteenth-century French intersex person who was forced to live as a man against until her death by suicide, the commune is a repository for traumatized young women whose gender is indeterminate for everyone but themselves.

That Byron’s debut comes out the same year that Torrey Peters is re-releasing her ten-year-old novella, Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, is a serendipity of sorts. Like Byron herself, Herculine’s protagonist, an aspiring writer who looks up to the Hot Freelance Girls (her nickname for the trans women writers who enjoyed a brief window of upward mobility back in the Buzzfeed and Jezebel days, when Representation Mattered), lives in the shadow of the now-defunct Topside Press literary scene, of which Torrey is perhaps the best-known member. Though it deals in demons rather than vaccines, Herculine shares with Infect cult dynamics contrasted with the sad suspicion that T4T isn’t the nostrum that some would have us believe. “Loving trans girls is hard, even when you are one,” our heroine reflects—and this is before the spinning heads and human sacrifice.

Sun City by Tove Jansson: Jansson writes perfect novels. The shifting perspectives of City’s tenderly wrought weirdos, freaks, and obsessive-compulsives, all living and working in a 1970s Floridian retirement home, coalesce in one of the finest, and strangest, examples of Americana I’ve had the honor of reading. “Few things are more pleasurable than a book about a place written by someone who loves that place, because true love will be as honest with shortcoming as it is generous with praise.” I wrote that about The Summer Book, set in Jansson’s native Finland, and it applies here, too, with her outsider portrait of one of the most vexed states in the Union. Jansson’s unflinching affection makes me believe that anything—even the truth—is possible.

What I’ve been looking at“The Clock”: Nes and I lost about 90 minutes in the dark MoMA staging room screening Christian Marclay’s 24-hour montage, which depicts a full day using only film and television clips that reference time: Meryl Streep in The Deer Hunter (1978), Nicolas Cage in the National Treasure franchise, a shootout in 3:10 to Yuma (2007). Watching it, you become hyper-aware of time while it flies by, a diverting yet numbing experience not unlike playing a very good video game. We could have stayed longer, but had somewhere to be.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Some of it—like somatics, inner child work, and lots of brusque but genuine affirmation—is startlingly familiar to us contemporary woo types.

2Even more quaint than the language is a state-funded American medical facility that is clean, comfortable, well-staffed, and seemingly operated without coercion (though this is, of course, part of the propaganda, too). Why, it’s positively European!

March 5, 2025

Body scan

Legs: Last time I wrote about how I eat. This time I’m writing about how I walk.

While I love walking, I often feel as if I do it incorrectly, as if the way I move from one place to another isn’t just clocky (a persistent concern) but ineffective, as if the thing that’s preventing me from moving naturally is also preventing me from moving at all (which of course isn’t true, or else how would I be getting anywhere?), and as if what’s natural must necessarily be optimal, and also as if there’s an essential walking style that I failed to learn at some point in my development, which doomed me to totter between two stiff, Bellmer-like limbs that I don’t have control over and which I wouldn’t know how to operate even if I did1.

And yet I do have some control over how I walk because of course I change it, as we all do, depending on where I am and who’s around, consciously and even unconsciously altering my shape and stride (length, cadence, weight distribution, and point of contact with the ground) from how it is when I’m home alone (putatively the most “natural” version of how I walk, though who can be sure) to something more suited to working in an office, cruising at a party, passing a group of men on the street, entering the women’s bathroom at Barclay’s with Jade (who looks like a woman), entering the men’s bathroom at the airport with Nes (who looks like a man), pressing through the dance floor toward the DJ, dashing through the train station, or finding a seat in my gynecologist’s waiting room. When I want or need to look less gay (which is sort of like passing as a man, but not quite), I square my hips and shift my ballast upward into my shoulders, although this intervention—like deepening my voice or dethroning my gestures—is a lot harder to maintain than you’d think. Sometimes the whole thing backfires, making me even clockier, and so What’s the point? I think, as I do when someone sees me at the beach in Speedo briefs and calls me Ma’am anyway, although fears of this minor kind of humiliation fly out the window when I’m not in New York City, a place where I mostly feel free to do what comes “naturally,” which is to mince in a way that my butch boyfriend loves to parody (which I find amusing and even validating, perhaps because it reinforces something that doesn’t always feel quite real to either of us and perhaps my dad used to do it, too, though without Nes’ good-natured self-awareness), because once you’ve been chased, or bashed, or asked to leave an establishment because you looked wrong—and a good 25-95% of looking wrong is moving wrong, I’ve learned—you’ll take your chances trying to pass, at least sometimes, maybe. I mean, I guess it just really depends, doesn’t it?

But of course, as I said, doing what comes naturally doesn’t feel natural when I’m in public, and the feeling just gets worse when I try to correct myself based on a series of hunches, experiences, and biases that have led me to the dimly-held conclusion that “correct,” in this context, the context of walking, means “not comfortable,” and so there I am heading down Driggs to the Bedford L or whatever trying to enforce symmetry between the left and right sides of my body2 while contradicting the instinctual movements of my arms, shoulders, and wrists before, during, and after I take each step, a process which entails the dicing of every moment of locomotion into stills that I continue to study long after they’ve become irrelevant, although whether this means from foot to foot or block to block depends on who’s watching and of course who’s watching includes me, because this whole time I’ve been observing myself in order to achieve my “natural” style of walking, that is, the way that looks the most normal, feels the most effortless, and gets me to Point B with a minimum of resistance, but since this style cannot ever really be known (that is, qualified, reproduced, and tested in any kind of systematic way), I’m shit out of luck here.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Just discovered a paper on “late medieval apotropaic devices against the spread of the plague” that depict vulvas on stilts! VULVAS ON STILTS. I, too, would feel safer from the evil eye with one of these bad boys in my cloak.

2Or the feminine and masculine sides of my body, from the traditional Chinese perspective.

February 19, 2025

Can a novel that only has cis characters be “trans literature”?

Regular DAVID readers may remember that my forthcoming novel, Casanova 20: Or, Hot World1, doesn’t have any trans characters. I began writing it in a state of exhaustion caused in part by the cis contempt elicited by my second novel, X, a fairly well-received little book with a trans protagonist. After that experience, I wanted off the ride! But since that’s not an option in this lifetime, I took my frustration out on a new character—a straight-identifying white cis man named Adrian—by cursing him with an extreme and unrelenting beauty. In this condition, Adrian would shoulder what the world offers gender-nonconforming people as our best-case scenario for a public life: a violent intersection of sexualization, objectification, and infantilization.

Can a novel that only has cis characters be “trans literature,” even if the author themself is trans? Must it be? In the past month, these almost rhetorical questions have graduated from artistic considerations to material concerns: can Casanova be said to be trading in “gender ideology,” as the Trump administration calls it, if such an agenda (should it exist) is only subtext? After the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) updated its grant application guidelines per Executive Order No. 14168, the answers could be the deciding factor if a transsexual like me were to seek federal funding for a new project2—like, say, my fourth book. Interpreted as the administration intends, these guidelines now bars all trans artists from NEA funding.

I wasn’t planning on applying for an NEA grant this year, but these new guidelines, ironically enough, brought to my attention the fact that I would actually be a pretty good candidate. What if, you know? But I’m lucky and privileged enough that I don’t need to rely on said funding to do what I do, and that’s partly because I knew going into this whole working-artist thing that I couldn’t rely on institutional or familial support. Like Riley MacLeod, who writes that while it still hurts to see such an explicit focus on erasing trans people from the arts,

I always thought this would happen, one way or another, and I built an artistic world that didn’t need such institutions to survive and thrive. These decrees aren’t some kind of “end” to trans art, and whatever overtures these moves make toward eradicating it can’t help but fail, because I don’t believe we’ve ever truly needed cis people’s support to do our work, and there is an entire world out there outside of national organizations and grants.

I take heart in this sentiment, if not much else3. Although I knew what January 20 would bring, this shock and awe is having its intended effect on my body. I’m fine—certainly more so than the friends, acquaintances, internet mutuals, and strangers who are suffering more uncertainty, deprivation, and fear. So why can’t I bring myself to eat? Why have my autoimmune symptoms roared back to life after one of the longest remissions I’ve ever had? Why do things with the potential to affect me directly feel sort of weightless, while the things that are, for all intents and purposes, personally symbolic (like those cowards at RAINN removing all mention of trans people from their website) cause me to break out in a cold sweat?

I mean, I know why. The body will do what it will. I’m grateful that this includes writing DAVID, so thank you for being here. For now, I’m going to get back to work.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Cassa, as my boyfriend calls it, will be published by Catapult (US) and Cipher (UK) this December.

2The new guidelines also ban the promotion of “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) programs that violate any applicable Federal anti-discrimination laws, in accordance with Executive Order No. 14173. I wonder how Black artists and artists of color, even the cis ones, can hope to secure funding with these guidelines in place?

3Although if you’re looking for something grounding, Sarah Thankam Mathews’ latest is a good place to start.

February 15, 2025

What I've been reading and watching

Since I last wrote one of these, I’ve watched a score of films, read seven or eight books (not including my own, as it moves through the copyediting stage), saved eight or nine interesting articles/essays to my “Articles/Essays” spreadsheet, and seen one Broadway play: “GYPSY” starring the sensational Audra McDonald as Mama Rose1. I wish I could write about all of it, but considering that I’m in the thick of the Valentine’s Day Extended Universe™ that is being polyamorous and, you know, everything else, I can only do so much.

I’m not really a trigger-warning type of person, but the book and film I’m reviewing today both depict graphic, terrifying violence. I recommend them very highly, with the caveat that I found them challenging to read and watch, respectively. Please take this into consideration before reading and be gentle with yourself when you can.

What I’ve been reading Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (out March 25)

Trauma Plot by Jamie Hood (out March 25)With her second memoir, a beautiful and formally original meditation on misogyny, memory, and art that’s at turns harrowing, lovely, and sharply funny, Jamie Hood makes a powerful case for trauma as a worthy literary subject. Challenging Parul Sehgal’s infamous takedown of the so-called trauma plot, Hood examines the now-trendy conflation of the “first-person industrial complex”—i.e., what happens when you convince marginalized writers that, as Jia Tolentino once put it, the “best thing they have to offer is the worst thing that ever happened to them”—with women artist’s personal stories of sexual violence. As Hood writes:

“What troubles me…is the wholesale idea of our relation to writing as unexamined, crude, and lacking in competence with self-reflexivity, humor, and play. Like there’s no reason to write about trauma except to make a buck. Like if you talk about having lived through something awful, that’s all you’ve ever talked about or ever will. Like you have no agency inside a story you yourself choose to tell.”

Grounded in her graduate studies of the modernist confessional, and in particular the work of her beloved “suicide girls” Virginia Woolf, Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton, Trauma Plot is in search of time lost to PTSD. Like a hall of dissociative mirrors, Hood’s series of past selves—speaking to us in the third, second, and first persons—navigate school, work, relationships, and therapy while fighting to live lives of pleasure and meaning under the specter of traumas repressed, relived, and constantly anticipated. Readers of Hanya Yanagihara’s novel A Little Life, one of Sehgal’s subjects, tend to clump into two camps: those who feel that its “accursed” protagonist’s suffering is realistic, and those who don’t. Hood’s own experiences with rape, poverty, substance (ab)use, and sex work, and the ambient violence that subtend them for women and queer people in particular, throw this schism into stark relief. “For me,” she writes, “[A Little Life] was one of the only novels I’d read that saw how pervasive intimate violence is in our lives, and how shadowy, how stigmatized, how great the pressure to stay stoic in facing it, to weather violence without complaint.” How can women writers who have undergone the unspeakable2 pursue “self-making” when their very lives have rendered them “unliterary?”

I’ve loved Jamie’s writing, particularly her criticism, for years now, but I didn’t want to read Trauma Plot, knowing it heavily featuring the epithet “rape girl,” which she used to disparage herself in the wake of the grievous violence done to her. I knew it would be too difficult, a suspicion confirmed within the first few pages; while interesting, engaging, and intellectually rigorous, Trauma Plot is a book I had to force myself to begin and to finish, crying on the G train in the process. Once, I literally threw it away from me, as if it were on fire. While I honor Jamie’s fear and despair, it’s her fury that gave me what I needed to make it to the end. Perhaps that’s what got her there, too. As she writes near Trauma Plot’s conclusion,

What I’ve been watching“But I have to remember I’m not writing this to be believed. I’m writing to open space in myself for other books, to offer solace—I hope—to others who’ve lived through this. I can’t write for my worst readers, and there’s no amount of evidence that would satiate people, there’s nothing to do or say that could make a person ‘good enough’ as a victim. It’s why people like us best when we’re dead. As if death is the only proof possible, like: oh dear, see what happened to that poor girl, and now she’s gone. Better we can’t speak. Better our corpses be the books left behind us, interpretable to everyone but ourselves.”

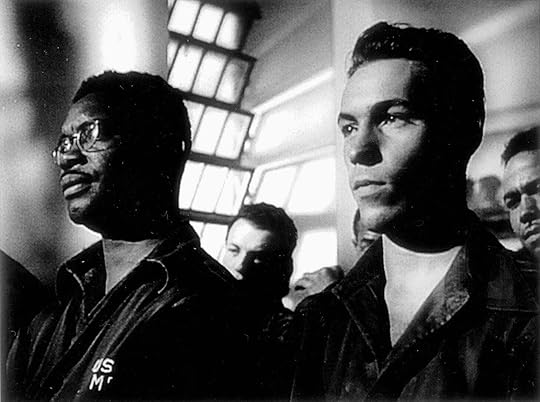

Nickel Boys (2024)

Nickel Boys (2024)David Canfield compared Ramell Ross’ first non-documentary narrative to The Zone of Interest (2023) in the way it “reinvents the language” for movies about a “dark historical chapter.” I haven't read the 2019 Colson Whitehead novel on which Nickel Boys is based—about Elwood and Turner (Ethan Herisse and Brandon Wilson), two Black teenagers incarcerated in a boys’ reform school in 1960s Florida—but its literary influence is obvious in Ross and cinematographer Jomo Frey’s approach to visual storytelling. Making use of symbolic interstitials—Southern Gothic aphorisms like eerie country roads and unexpected gators—as well as surprising yet fluid inversions of perspective, Ross and Frey show us that much can be seen, and even exposed and revealed, when the eyes are averted, whether from fear, submission, or dissociation.

This is not to say that Nickel Boys is a work of misdirection. We see unspeakable, but unfortunately still see-able, acts of violence, primarily against Black children and young men. It made me afraid, disgusted, triggered, angry, and despairing. At one point I thought about leaving the theater, but something inside me said, “No, you must witness this, especially because you’re white.” But then something else inside me said, “Okay, that’s actually stupid.” While I did stay, I actually didn’t have to, white or not, and doing so didn’t do anything for the people who suffered the very real, and ongoing, injustices that Nickel Boys renders. When analyzing this work of art, I think makes more sense to think about what is gained—that is, what my body learns—by seeing and hearing it, despite myself.

If Nickel Boys had any lesson for me, personally, it’s that suffering together in acts of defiance is heaven compared to suffering alone. I think this is something that I know intellectually, but that needs to be known by my body, perhaps reiteratively, in order to keep it that way. If art can do anything, it’s preparing you to learn this lesson in real life, or reminding you of the times that you’ve learned it in the past. Because although Nickel Boys depicts a great deal of physical and spiritual abuse, some of its most wrenching moments are when a person reckons with it alone, whether because they are forced to, or because they cannot bring themselves to share it. Luke Tennie as Griff, a Black boy who is murdered for not throwing a fight with a white boy put on by the white man (Hamish Linklater) who runs the camp, gave such a powerful performance of loneliness that I forgot what that he was an actor; in the boxing ring, his cries of rage, frustration, and fear before making his fatal error (suicidal choice? overwhelmed mistake?) were almost more affecting than the more straightforward scenes of nightmarish physical brutality. Torture is dehumanizing, which is why people resist it even when that resistance leads to even worse suffering, if not death. But as Nickel Boys shows us, this resistance has its costs, in the present and far into the future, so much of it manifesting in isolation—the price of survival.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Jade’s Aunt Laurie got us tickets. Thank you, Aunt Laurie!

2I love how Hood eviscerates this canard. “[T]rauma has a language; we just convince ourselves otherwise so we aren’t forced to face it. Or perhaps we’re convinced it’s unspeakable by those who wish us not to speak it, who know silence protects them. So someone says being gang-raped is ‘beyond’ representation, a statement that’s demonstrably untrue…I’ve written one hundred thousand words on my trauma. Is that unintelligibility? Rape effaced me and yet I speak it. It stole my face and my name, and I’m still fucking here. It remains in me. We live in rape’s presence, and its presence infests us. This pretense of wordlessness is a tool of the tormentor. It doesn’t serve.”

February 10, 2025

An aging homosexual becomes set in their ways

I love my weekdays because they’re almost always the same. Just thinking about this sameness provides a satisfaction that’s almost better than pleasure. Having laid out this itinerary, I return to it over and over again, like a penitent to her rosary:

7:30 am: Wake up without an alarm.

7:30-8:00 am: Stretching, yoga, or light calisthenics. Tidy room.

8:00-8:15 am: Shower and dress.

8:15-9:00 am: Make pour-over and eat breakfast (lately it’s been oatmeal with peanut butter and a few dates to balance the coffee’s heavenly bitterness). If there’s time, read or listen to the news1.

9:00 am: After saying goodbye to Jade, begin the day’s work at the desk a few feet from my bed.

Weekends I love less. Unless I’ve been out until dawn the night prior (an increasing rarity), I don’t sleep in anymore. I wish I could, if only for the indulgence of it, but I don’t need to like I did in my twenties, when I was always stringing together three jobs working swing shifts, graveyards, and overnights. What’s more, every lost morning hour feels like two, especially if the rest of the day isn’t spoken for. For someone like me, anything could happen is not promising, but a threat. It’s not that I’m itching to be busy all the time—I’m actually quite lazy. But for anything to feel either productive or restful, it has to be on my terms, which are, invariably, that I have decided to do it in as far in advance as possible.

“Aging homosexual becomes set in their ways,” is a cliche that I’m beginning to see in a different light. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to recognize which “ways” serve me—order and consistency—and which don’t—spontaneity and surprise—and have adjusted accordingly. I still welcome variety but only in specific contexts, if you can even use variety to describe the punctuated chaos I occasionally, almost dutifully, permit myself. I’m reminded of Jorge Luis Borges’ “The Lottery of Babylon,” about a society in which a game of chance has been imposed upon all citizens, creating a “monstrous variety” in which both luck and misfortune are constantly at play. The story begins: Like all men of Babylon, I have been proconsul; like all I have been a slave.

As an artist, I’ve found that the most effective discipline is not imposed, but embraced with a desire bordering on desperation. Discipline is not a box within which the work is found, but a scaffold upon which it is accomplished. (As I’ve said before, I think of art as disciplined play. Not far off from what you were doing as a kid, only now you’re the one deciding that it’s time for recess.) I guess what I’m trying to say is that discipline makes your life easier, so if your version of it isn’t doing that, it might be worth giving it some more thought.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1Democracy Now! or Heather Cox Richardson’s daily “Letters from an American.”

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 56 followers