Davey Davis's Blog, page 7

September 20, 2024

David Davis

I love these quarterly check-ins. This time, I’m including a few movies and a painting, but I’ll only be talking about one book (kind of). Though I had a fun summer with Alan Hollinghurst’s The Swimming Pool Library, Gary Indiana’s Rent Boy, and Joan Nestle and John Preston’s Sister and Brother: Lesbians and Gay Men Write About Their Lives Together, plus a few others, there are only so many hours in the day—especially when you’re wrapping up the MS for your third novel.

What I’ve been readingStag Dance: A Novel & Stories , by Torrey Peters

In 2019, a few months after I moved to the city, Torrey Peters invited me to lunch. I had read Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones, but that was all I knew about her, if fiction can tell you anything at all about its author. She arrived at the restaurant on a hot-pink motorcycle, briskly unhelmeting the golden hair that doubled as her lit-girl aureole (Detransition, Baby was just around the corner), before greeting me with her disarmingly soft voice. She was polite in the self-effacing but deadly serious manner of Midwesterners, instantly putting me at ease, or what passed for it at that time in my life. Over our meal, we talked about writing.

We still do. Reading my ARC of Torrey’s newest book, Stag Dance—comprised of Infect Your Friends, two other novellas, The Masker (2016) and The Chaser (2020), and the eponymous novel, a tall tale-style yarn about gender trouble at a turn-of-the-century logging camp—I had the funny, pleasureful, obvious-in-retrospect realization that our friendship lives within our books, each a long and painful gestation of chapters nurtured, abandoned, executed, revivified, fretted over, and then finally whisked away into the world. (I’m mixing my metaphors here, but considering our oeuvres I think a little biological illegibility is in order.) Over the past five years, we’ve talked about everything under the sun, but there’s never a conversation with Torrey that doesn’t somehow find its way back to our work.

While Stag Dance the novel is new material, Stag Dance the collection has the shape and feel of a retrospective, which is highly appropriate for a brilliant though still-maturing artist who has managed to survive the (well-deserved) hype and circumstance of her debut, which included her nomination for the 2021 Women’s Prize for Fiction, as well as its transmisogynist outcry from an unwashed minority whose open letter against it could have used a copy edit. As Torrey writes in her acknowledgements, Stag Dance brings together a decade of work that has “[puzzled] out, through genre, the inconvenient aspects of my never-ending transition—otherwise known as ongoing trans life,” with stunning and satisfying consonance.

In my brief review of each novel/la, I’ll keep it as impersonal as I can under the circumstances. But I will say, unprofessionally, that I see in Stag Dance’s successes the qualities that I adore in Torrey as a person: her delicacy; her sense of humor (highly sophisticated, with gleeful glimmers of adolescent raunch); and her uncanny ease with metaphor, as if even the most complex idea were merely an apple for her to lower into your reach by applying just the right amount pressure to its branch.

Infect Your Friends and Loved Ones: I had forgotten how cinematic this one is. In a post-pandemic future where everyone is trans—or rather, where everyone is forced to scrap for the sex hormones that keep our hair and muscle and fat in the preferred states and locations—our narrator toggles between her apocalyptic present foraging for estrogen and her no-so-distant t4t past with Lexi, the messy doll who started it all. Now that we’ve actually had our viral plague here in the real world (though it hasn’t fucked with our endocrine systems in a way that’s quite so interesting), aughts/teens spec-fic (mine included) has acquired a certain naiveté. For all its technical irrelevance, however, Infect Your Friends retains the narcotic charisma of transsexual littermate lovers, a page-turning momentum, and the breathless final grafs that made it pop in the first place.

The Chaser: We return to the scene of the crime—adolescence—not from the perspective of the gender-funny kid, but their grudging admirer. At a Midwestern Quaker boarding school, a butch jock gets involved with his roommate, femmy proto-girl Robbie, only to discover that detaching with his masculinity intact is harder than he would have guessed. There’s so much to love about this story, which I think remains my favorite of Torrey’s work, but what I love the most is that Robbie has the social status and emotional intelligence to be its villain, rather than its victim—the chaser’s chaser. But this reading begets another: that Robbie is not the villain at all, but simply insisting on not being disappeared by his erstwhile friend, which, in a world in which men are gendered through the de-gendering of other people, can only be understood as violence.

Stag Dance: Because Stag Dance is boldly written in dialect and because I have heard Torrey recite from it at “Trans Disruptions: The Future of Change,” reading this novel gives me the hilarious sensation of seeing my willowy friend in drag as bewhiskered Babe Bunyan, the self-loathing, ox-sized yeoman who yearns to wear the fabric triangle that will mark him as “the skooch” to be courted at his logging camp’s stag dance. Poised against his rough-hewn ribaldry is Torrey’s strongest setting and descriptive work yet, as well as her always-original approach to gender as a thing we desire more than inhabit. As Babe, triangle firmly in place, muses, “Maybe the order of events is jumbled, but it seems that the declaration and the aspiring happen in the same moment.” Ok, backwoods Judy Butler!

The Masker: Not all transsexuals have a red-pill moment, but for many of us an excruciating decision must be made: do I go full-time? Force-fem and sissy interiority (do you know the difference between a woman’s garment and a sissy’s?) is Torrey’s bread and butter, and so long as there is a social cost to transition, particularly for women, her essential treatment of these topics will continue to fascinate.

What I’ve been watchingAll That Jazz (1979): I love art about people who are terrified of sex, and few are more so than Bob Fosse’s semi-autobiographical stand-in, theater director, choreographer, and compulsive philanderer Joe Gideon (played by the gorgeous Roy Scheider, as I always call him). As a musical theater hater, I was nonetheless thrilled by Jazz’s beautiful choreography, fabulous casting, and mesmerizing assembly; its writer clearly has an intimate understanding of rhythm. Still, I spent most of the screening wishing I were watching 8½ instead.

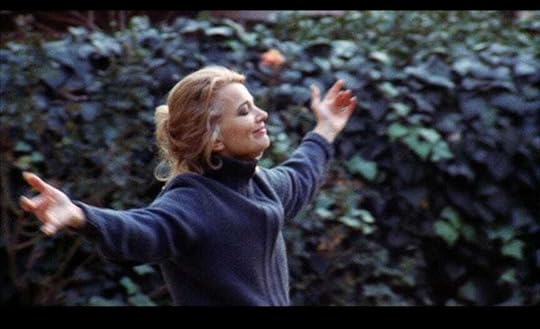

A Woman Under the Influence (1974): Watched it again because of Gena Rowlands’ passing. For a loud movie, Woman has many moments of profound quiet. Though its scenes of naked tragedy, including the one where Rowlands’ Mabel begs her husband, Nick (a heartbreaking Peter Falk) not to institutionalize her, may draw the most attention, for me the most memorable is when Mabel waits on her tiptoes in the street for her children’s school bus, almost dancing with happy anticipation. It made me miss my own mother in a way that was almost not unpleasant.

Greta (2018): This one should have been drowned in a bucket. A crazy piano teacher living in New York City stalks, tortures, and kills young girls, and yet we’re bored. Chloë Grace Moretz stuns—in the bad way—and even the great Isabelle Huppert is wooden and unsatisfying, though she chews up one or two scenes, like when she forces her victim to serve her in the restaurant where she works.

The Spook Who Sat by the Door (1973): Both brilliantly understated and depressingly on the nose, Ivan Dixon’s radical adaptation of Sam Greenlee’s novel follows the first Black CIA agent (a slow-burning Lawrence Cook) as he builds a guerrilla army intent on overthrowing the government. The FBI had it pulled from theaters, and I can’t imagine it would fare very differently as a new release today.

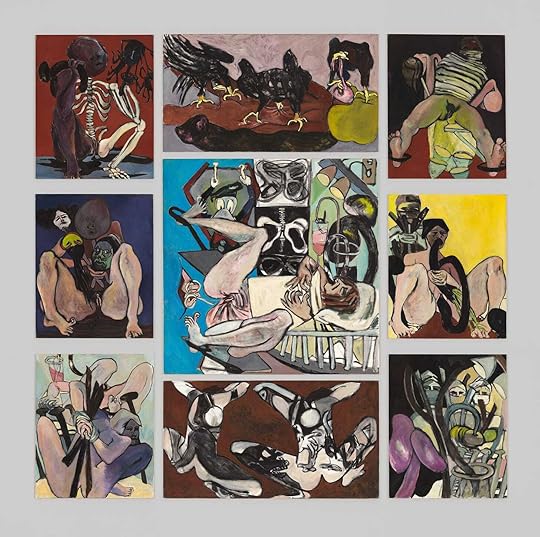

What I’ve been looking at“Is It Real? Yes, It Is!” by Juanita McNeely: Going through my notes, I came across a photo I took of the Whitney placard for this painting, a depiction of the artist’s experiences with illegal abortion because legitimate doctors would not do it in order to save her life from cancer—to protect the baby, you see. Even while acknowledging the brutal circumstances of her procedure, the placard describes the “cruelty and carelessness” of her male doctors as “perceived.” Every time I read the word, I become livid. I have not had an abortion, but I have been butchered; this painting, with its necrotic bones, suffocating bandages, leering Donald Duck, and faceless MDs stopped me dead in my tracks.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

September 11, 2024

David Davis: Members Only

You may have noticed that images from my scenes are almost always paywalled. This is because I understand that “content” that is personal, eroticized, and involves me doing something freakish is more likely to inspire you to subscribe than reviews of interwar French novels or meditations on the romcom. While I believe that people like reading what I have to say about art, culture, and leather, I understand that what people like is rarely the same thing as what they’re willing to pay for.

It’s for this reason that the violence is below the cut, as it were.

David Davis

You may have noticed that images from my scenes are almost always paywalled. This is because I understand that “content” that is personal, eroticized, and involves me doing something freakish is more likely to inspire you to subscribe than reviews of interwar French novels or meditations on the romcom. While I believe that people like reading what I have to say about art, culture, and leather, I understand that what people like is rarely the same thing as what they’re willing to pay for.

It’s for this reason that the violence is below the cut, as it were.

September 7, 2024

David Davis

Last week, I received a call from a man looking for my uncle, who apparently owes him money. It wasn’t out of any sense of loyalty that I blocked him—I haven’t seen my uncle in ten years, since he was running a scared-straight/conversion therapy racket on his property out in the Sierras. Out of curiosity, I tracked down the Instagram account for the now-bankrupt business he started with the money of the man I blocked; in dipping his toe into a new industry, it seemed, my uncle was soon lost at sea.

I examined the photos of him and his family, who, in true Davis fashion, were also his employees. Other than looking older, little about them had changed in the past decade. From my uncle’s frizzy, Viking-style beard, to his wife’s baggy, joyless dresses—femininity-as-chore for the woman he referred to as “Mother”—to his children, the drab young adults who I suppose are my cousins, these biological relatives of mine are the worst kind of white people: Disneyfied versions of the more aesthetically striking skinhead who harbor more or less the same politics.

I felt nothing for them. But blocking my uncle’s creditor still felt vindictive, rather than merely practical, and I was out of sorts for the rest of the day. Though it smarts to be deadnamed (as will happen to me forever thanks to the digitization of legal and medical records), my resentment had been stirred by this reminder of my natal family and my lack of feeling for them. These reminders of nothing, which aren’t unfamiliar to me, always have the paradoxical effect of making me feel something in the most unpleasant way.

Also last week: bored and over-caffeinated, I did an anonymous AMA on my own Instagram. Among the submitted questions—What are my romantic relationships like? What do I think about this or that director? How have I integrated COVID safety into my sex life?—was this one: Why don’t we have a good written ethics of sadism?

I’ve condensed the question for you here, meaning you can’t see how its considerably longer original phrasing telegraphed, to my ears, a proud ignorance of leather and a disdain for the sadistic experience, something about which, as a masochist, I feel called upon to defend; I’m also suspicious of people who came to leather through a college critical theory course rather than, you know, gay sex, as they tend to arrive with a lot of bourgie hangups about a subculture that is definitionally poor, criminalized, and otherwise marginal1. Despite my irritation, however, I replied with lots of recommended reading—because how could I blame this person? These days, leather seems more accessible than it really is because its signifiers have been commodified by marketing and pop culture, and its body, if not its underbelly, exposed, via social media, to people (gay and otherwise) who have no actual stake in the lifestyle. Why don’t we have a good written ethics of sadism? Not that we need one, my dear, but how dare you assume that we don’t?

In my response, I included Guy Baldwin’s Ties That Bind: The SM/Leather/Fetish Erotic Style: Issues, Commentaries and Advice [sic]2, a collection of his Drummer advice columns from 1986 to 1993; it’s not theory, which I think is what my interlocutor wanted, but I thought a psychotherapist leatherman’s perspective had something to offer, ethically speaking. At around the time he was writing that column, Baldwin also wrote a series of essays on leather’s Old Guard, having discovered that the younger leatherfolk around him insisted on conceiving of these mystical creatures as this “rigid and dead thing rather than an evolving, living cultural entity.”

“Stranger still,” he writes in “The Old Guard: Classical Leather Culture Revisited,” “is the fact that the Old Guard is usually talked about by people who weren’t part of it as though it were some kind of monolithic, behemoth…homogeneous and static, neither of which was the case…”

Ignorance is no sin, especially when it comes to leather, a subculture that has been repressed and co-opted since the beginning. To revel in one’s own ignorance while disparaging that about which one knows nothing, however, is to display an arrogance antithetical to our tradition, which that Instagram person would have known if they had read beyond the sexy university press releases of the past year or two. Mama, let’s research the American homosexual military veterans who split off from The Wild One-style motorcycle gangs of the 50s to create their own hierarchical rough-fuck culture!

To be sure, the leathersexuals that came before us aren’t unproblematic. Baldwin uses language like “feudal nobility,” “godfather,” and “baron” to help us conceptualize the way that leather families were organized among the white, cis, masculinist players of the 50s, 60s, and 70s. One was not socialized into leather as a vast, interconnected, highly political counterculture—movement, even—but into the norms, mores, and protocols unique to their region, city, and family. These “clans” or “tribes” subverted the nuclear family while also reproducing its organizational logics of white supremacy and patriarchy (power relations that define leather today, by the way). Nevertheless, they served an important purpose for leathersexual men, supplying, as Baldwin writes: “advice for love life and sex life; a home-life with our own kind; information about how leathersex worked; a place to barbecue on weekends; information on who were the responsible players in the community and who was best avoided; the very important Protocols, of course; and general mentoring.”

Unlike Baldwin’s Old Guard, my leather family is multi-gender, multi-racial3, and only incidentally ex-military (no one I know fucks with vets who haven’t been radicalized by their enlistment, denounced American imperialism, etc.). But both serve as replacements for our straight families of origin, who not only didn’t want us, but were incapable of supporting our safety and happiness as leathersexuals. The nuclear family is for reproducing capitalism; the leather family is for fucking.

In stark contrast to the way leather’s insularity has been on the decline since Stonewall (Baldwin has a lot to say about why this is), I suspect that our families have never been more important to that safety and happiness. But the Old Guard wasn’t just designed to protect its members: it also guarded “the mysteries of leather ritual” from outsiders, those who would have “exploited them for theatrical effect, chic, or merely from dilettantism .” Though the Old Guard has faded away, based on what we see of “S/M” in ad campaigns, TV shows and books, and social media, some things never change.

In 2024, the “mysteries of leather ritual” are not hidden from view in Brooklyn’s leatherqueer scene. At Bruise, the public monthly party put on by Daemonumx and Jade, there is no cover or dress code, although horny leatherwear is highly encouraged. While most of us who come are perverts, no one is turned away. I think this is a good thing, and compatible with the time and place in which we find ourselves: “we recruit,” as the Lesbian Avengers used to say.

A few weeks ago, Bruise hosted a pop-up strip club to fundraise for DecrimNY (fundraising is an old biker and leather tradition, as Baldwin writes). As sex workers, strippers are naturally adjacent to leather, and the dancers at the fundraiser were intentionally in leather, meaning they are parents, siblings, and children of other leathersexuals. As I watched them being sexy for their community, I felt like a sister, an aunt, a mother, even: Isn’t she beautiful. What a good job they’re doing. Look at him go! Watching their friends and lovers use infantilizing terms of endearment like baby, hold cameras like proud papas, praise them and cheer them on as they leap, spin, bounce, hustle, and throw ass, I felt old, or maybe just young, because these are the feelings I still associate with my straight family, and the life it was supposed to give me.

That these feelings—reflexive and nostalgic, natural and unnatural—can transcend my old life feels good. But I can’t feel them without thinking of my old life, which feels painful. Despite everything I have gained by that loss, I still grieve it, even though, if you could see my uncle’s work Instagram, you would wonder what there could possibly be to grieve. I think I always will.

Support DecrimNY.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1I went to college! I have bourgie hangups! And I came to leather because it was the only way to survive a bad situation, which means I accord it a respect that weekend-warrior trust fundies just don’t, maybe can’t.

2Not to be confused with Ties That Bind: Familial Homophobia and Its Consequences, by the great Sarah Schulman.

3I don’t remember Baldwin writing about race in his book, and glancing through his other writing—including a book on “slavecraft” (with an intro by Patrick Califia!!!)—there is nothing addressing race, racism, or white supremacy. Without making any claims about Baldwin’s personal beliefs, or going so far as to assume that he has never written about these topics, I am going to hypothesize that his milieu was pretty white.

August 22, 2024

David Davis

Whenever a celebrity makes the rounds for supporting the Zionist entity, Twitter leftists like to point out that the most noise tends to come from the most mid among them. When you’re C-list—at best—execrable politics, the logic goes, comes with the territory. See: Debra Messing, Mayim Bialik, the Good Wife, etc.

While it’s a tempting conclusion to draw, I think there’s another explanation. A-listers and Oscar winners like The Rock, Natalie Portman, and Jerry Seinfeld are also public about their Zionism, but the Michael Rapaports1 of the world are the ones building brands off of it. Like JK Rowling, who was already a billionaire before transphobia became the brain worm that Ratatouilles her smear campaigns against , Gal Gadot endorses genocide for the love of the game. Downstream of heavy hitters like them, however, are thousands of shills, opportunists, and mercenaries carving out their niche in an attention economy that rewards outrage, normalizes fascism, and embraces the dehumanization the thousands—possibly hundreds of thousands—of human beings who have been slaughtered since last October as not just the status quo, but emblematic of America’s moral righteousness.

I first recognized this phenomenon when it started cropping up around the that’s brought transphobia to a fever pitch here in the Anglosphere. How many journalists, writers, comedians, artists, influencers, and content creators have pivoted to virulent transphobia as the industry crumbles around them? The media jobs are going away as worsening labor conditions and stagnant wages are the norm across the board, while most of the country struggles to survive backbreaking debt, skyrocketing inflation, and the criminalization of homelessness amidst record housing insecurity. And it’s not just those of us in production who are being affected: as performers, even the big names we presume are loaded, become even more vulnerable, other income streams are needed.

I’m not saying that people like Rapaport aren’t genuinely genocidal ghouls. But even if I were, why would it matter? Your heart is your actions. Whatever motivates you, whether it’s a quick buck, honest racism, or a desire for Christ’s return to earth (this was the Zionism I was raised on), baying for the slaughter of Palestinians is white supremacy and colonialism, pure and simple.

It’s for this reason that I wanted to share some recent writing and reportage about Palestinian liberation I’ve come across lately. If these writers and culture workers aren’t Palestinian themselves, then they’re accomplices in their struggle in a context that censures all conscience with the most unctuous of liberal propaganda and the most violent of political repression.

Many of us have been following Peabody-winner Bisan Atef Owda on Instagram for months, if not longer. After Owda was nominated for an Emmy earlier this week, 150 entertainment industry “leaders” (including Messing) demanded that the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences (NATAS) rescind the nomination. Here’s how NATAS responded.

For Vittles, Mira Mattar wrote a powerful essay on starvation as a tool of genocide. Gaza as microcosm, laboratory, and proving ground of capitalism’s ravages—including climate collapse—is an evergreen observation worth repeating here.

I’m not big on poetry, but I was riveted by scholar Marina Magloire’s exploration of the Black feminist falling-out between June Jordan and Audre Lorde (feat. Adrienne Rich) over Zionism. “Jordan is lesser known nationally and internationally than Lorde,” Magloire writes, “and it seems to me that her decades of unwavering support for the Palestinian people is partly responsible.”

Vicky Osterweil’s always-astute coverage of the American political situation and resistance to fascism leaves me foundering in despair and brimming with hope (for those stuck in despair mode, here’s one she wrote on how to get organized/start organizing).

What these people are saying is important, which means supporting them in material ways—with money, with exposure, with solidarity—is important, too. If you can, I hope you will.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1The actor who famously looks like he “wakes up and dies every day.”

August 17, 2024

David Davis

Body scan

Body scanBrain: For my last body scan, I wrote about giving up my daily weed habit of many years. I felt as if I was beginning a new chapter. Now I’m not so sure.

My diagnoses of various mental health disorders began in my childhood, so this bad brain stuff isn’t new to me. But last year, it took a new shape with panic attacks that tend to cluster across stretches of weeks or even months at a time; once I have one, I must be careful for the next fortnight, as my baseline anxiety is heightened and my triggers are more sensitive. Since then, air travel—already dreadful, as veterans of the trans-induced pat-down are well aware—has begun to generate its own panic zone, this intense irritability, paranoia, and terror that manifests as a racing heart, the urgent need to urinate (that is, a hyper-awareness of my bladder and genitalia in one of the locations where it’s most stressful to safely access the bathroom), akathisia, derealization, the fear of imminent death (paired, absurdly enough, with suicidal ideation), and a unique strain of dysphoria that makes me feel like Gregor Samsa.

While these acute symptoms define the panic attack itself, its attendant zone can begin days before and end days after my flight, which means my regular anxiety also spikes, intensifying my day-to-day hypochondria and germaphobia, insomnia, suspicion that everyone around me is trying to rape or kill me, blah blah blah—that is, everything I used to manage pretty well with weed since testosterone gave me a reason to live1. Last week, when Jade and I flew together for the first time since early 2023, the contrast was obvious to both of us.

Jade used to joke that I was never allowed to stop smoking weed or doing yoga, as both, along with my pain practice2, have kept the bugs out of my walls for many years at this point. I was proud of my first non-white-knuckling attempt at life without cannabis, as if this highlighted all of the work I’ve done to feel my emotions, regulate my nervous system, and stay in touch with reality. But of course, these things are hard for some people to do even in the best of circumstances—and the “best of circumstances” is still a cursed world in which my life happens to be one of the easiest.

I don’t crave weed in the least, but a couple months into this experiment, I am reconsidering it. This makes me feel very discouraged. But I don’t want to want to die. I don’t want to wonder if Jade, who has never so much as raised her voice to me since the day we met, secretly wants to kill me. I don’t want to be overwhelmed by my hatred of cis people and fear of men. The disadvantages of staying high being as minor as they are compared to these specters, the choice seems easy enough.

But there is something in me that still resists it. Whatever that is—pigheadedness, a problematic desire for the “cleanliness” of sobriety, the self-harming instinct that has always been there since I was just a little redacted—I’m letting it stay my hand for now. I guess I’ll have to wait and see.

Eyes: From April to October, I never go into the sunshine without my sunglasses. When I started hormones, I no longer needed the sensory-numbing accoutrements that I relied on to leave my apartment for so many years: baseball cap, headphones, all-weather dysphoria sweatshirt. But the sunglasses stayed, like Roy Orbison, a big love of mine. When I was a kid, someone told me that Orbison had been blind, but that was just a rumor that began when he was forced to do a concert in his prescription sunglasses after he left his regular ones on a plane3. People dug the mysterious look so much that it became his signature.

When Jade and I arrived in Mexico, we made the forced but nonetheless sensational decision to rent a car. As she got behind the wheel, I quickly braved the midday glare to clean the lenses, squinting like a mole in the white-hot sunlight. My eyes were safely darkened again by the time she pulled out of the parking lot and onto the deserted jungle highway, where, under clouds of ponderous pale butterflies, I waited for my girlfriend, an excellent driver, to crash and kill us both in brutal repudiation for a moment’s inattention.

Forearms: For the first time in my life, I’m getting acne on my forearms. Not a lot, but even a little seems excessive when it’s never appeared before. I take finasteride to keep my hairline, which means even though I’m injecting 40-50 mg of testosterone cypionate every week, I don’t grow a lot of body hair and still get my period (the FTMs of Reddit refer to this as a nonbinary-style approach to transition).

I’m sure this new development has to do with my cycle—the symptoms of which have changed lot, now that I’m no longer on my factory settings—but I don’t track it, so I’m not sure which phase it correlates to. My boyfriend does track it, however, so I’ll have to ask him.

Belly: In the Yucatan Peninsula, those butterflies are everywhere, even the beach, levitating above the surf: white clouds, white wings, white foam, white sand. Though Jade and I apply sunblock more frequently than most—I set an hourly timer when we go to Riis—the water cooked the skin over my torso over the course of a poorly chosen half-hour. Just the front, not the back.

I think I’ve made this mistake every time I’ve gone swimming in a warm ocean, which isn’t that many times, but enough to know better4. Though the burn faded by the next morning, my skin did feel sensitive for a few days. I’ve always tanned easily. My dad used to say it’s because someone in our history was Serbian, a bizarrely specific source of shame for the racists on his side of the family.

Feet: I did it. After years of dithering, I bought my first pair of Crocs. They’re black, with sparkles, and they’re amazing. I don’t want to wear anything else, and for the past few weeks, I haven’t. I can’t wait to pair them with thick, cozy socks when the weather gets cold again.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of fundraiser for Palestinians trying to survive within Gaza or relocate to safety. Gaza Funds is one place to get started.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1I have a Xanax prescription that I don’t like to use because boy oh boy is “habit forming” an understatement!

2I think of masochism as part of a larger effort toward mindful embodiment, achieved through practices like yin, meditation, psychoanalysis, and being a person in a community.

3I’ve worn mine at the movie theater when I had no other choice and it was actually so fine.

4Actually, I think the Indian Ocean may be the exception.

August 9, 2024

David Davis: Members Only

I only have three small, stupid tattoos from when I was 20 or 21. These experiments taught me that while the process itself is interesting to me, I’m just not a tattoo person—I dislike making aesthetic decisions, commitment, and spending money. Small as they are, I often think about getting them removed. Maybe I will someday.

I was raised to think of tattoos as either sins (my Boomer dad) or as expressions of self-realization, embodiments of endurance tests that may not have left a physical mark (my Gen X mom)1. Being in various communities that overlap through body modification, I now know a lot of heavily tattooed people who have a different relationship to all that ink: it makes them feel better about their bodies. While I found this surprising at first, I also immediately related to it: bruises make me feel better about my body.

David Davis

I only have three small, stupid tattoos from when I was 20 or 21. These experiments taught me that while the process itself is interesting to me, I’m just not a tattoo person—I dislike making aesthetic decisions, commitment, and spending money. Small as they are, I often think about getting them removed. Maybe I will someday.

I was raised to think of tattoos as either sins (my Boomer dad) or as expressions of self-realization, embodiments of endurance tests that may not have left a physical mark (my Gen X mom)1. Being in various communities that overlap through body modification, I now know a lot of heavily tattooed people who have a different relationship to all that ink: it makes them feel better about their bodies. While I found this surprising at first, I also immediately related to it: bruises make me feel better about my body.

August 6, 2024

David Davis

This weekend, my boyfriend helped me move into my girlfriend’s apartment. I’ve lived with partners before, but swore it off after last time, when I shared a cozy one-bedroom with someone who did not like me—and made sure I knew it—for two years.

“It’s because you didn’t have a room of one’s own,” Liz used to joke, with whom I’ve lived as lover and roommate in a few different permutations over the years. Liz probably invoked Woolf because we talked about her when she and I met in college. Along with Angela Davis’ autobiography, Gloria Anzaldúa’s Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza, and Barbara Ehrenreich’s Nickel and Dimed: On Getting By in America, A Room of One’s Own awakened real thinking for me, giving me words and concepts—like patriarchy, white supremacy, and class struggle—to express the political scaffolding of the world I lived in, ultimately shaping how I understood myself as an adult. I became a feminist shortly before meeting Liz, and a dyke shortly after. Classic stuff.

While I no longer strictly identify with feminism or dykery, their afterlives have led me here: to a shared apartment in Brooklyn with Jade, her cat, and a few other gay people. Although I now claim to think it was inevitable, both of us spent the majority of our almost-five years together declaring that we would never do this—live together—because Jade, too, has a dirtbag haunting her misspent youth.

Despite our well-earned distrust of heterosexist notions of family-building, I think Jade and I are handling all this pretty well. We talked about it a lot beforehand: our fears and anxieties, our preferences and hopes, and what the exit strategy would be if we couldn’t make it work. We both certainly stand to gain from this arrangement: less time and effort spent traveling back and forth; cheaper rent (this one’s for me); more manageable distribution of housework (this one’s for Jade, since I work from home); more socialization for her cat, Marcus, whose agita manifests in very annoying early-morning wailing; and more time together in an increasingly fearsome world.

But for all the advantages moving in together presented, I was hung up on the sacrifices it would require, particularly the ones having to do with my privacy, freedom, and various fantasies of independence. Without a mile between us, how would Jade and I negotiate visits from my boyfriend, Nes? Would I feel resentful if I couldn’t host trade whenever I wanted? What if I lost my mind because I couldn’t be completely alone literally whenever I wanted, as I could when I lived by myself?

Notice that these sacrifices only belong to me. I was well aware that Jade would have apprehensions of her own about moving in together, but they didn’t feel real until she laid them out. She isn’t dating someone else currently, but what if she eventually does—would I cramp her style? Would she feel smothered by having someone living and working in her apartment? With me in the adjoining room, when would she have the chance to let her hair down and be a “goblin” ?1 Learning how and why Jade felt protective of her space made me feel less protective of mine. I don’t think I’m a perfect roommate, but I do sometimes forget that not everyone—especially my best friend—is out to get me.

The true tests of this experiment won’t come right away, I don’t think, but it’s safe to say so far, so good. I feel lucky that Jade wants to live with me. Every time I feel vulnerable here, in someone else’s home, I remind myself that it’s just as vulnerable, maybe more so, to invite someone in. I’m not sure I could have done it.

I think Jade likes it, too. Over the past few days, she’s been saying stuff like, “Wow, I can’t believe you really live here!” and, “I should book a session with my old therapist just to tell her.” It’s nice when surprises are pleasant. Sometimes, in the pleasantness, we find that they weren’t even surprises to begin with.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of the fundraisers featured on Gaza Funds.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

1As far as I can tell, this means eating a snack in bed with a t-shirt on, which Jade and I do together most nights, anyway.

July 27, 2024

David Davis

I read somewhere that the poet Robert Lowell would buy copies of his books to mark up with his red pen. This is the approach I take to DAVID, which I’ve been writing for over four years now. Though unfortunately I can’t delete what’s already been sent to your inbox, I’ve definitely zhuzhed up live posts and even unpublished a few. Because despite my best efforts, I’ve written a lot of crap! Weak theses, tortured sentences, meandering arguments, you name it. (Thank you to everyone who’s stuck it out with me—it can never be said that you weren’t true patrons of the arts.)

Writing well is hard, and I do it very rarely. I know there will always be mistakes and changes of heart; I have accepted that clunkers are a part of my past, and my future, too. And then there are the labor conditions: the compensation I receive for my books, freelance articles, and newsletter is so low that I must subsidize my “career” with a full-time job—which means I am effectively paying to be published. If I didn’t enjoy my work, the humiliation wouldn’t be worth it. But I do enjoy it, and so I wake up every morning, pull my pants on one leg at a time, and get back out there, eager to debase myself once again.

Not to brag, but this attitude has served me well. It’s granted me the ability to accept that my pristine first draft is actually super busted, as my editor will confirm. It’s allowed me to read good reviews with gratitude and bad reviews (and by this I mean everything from bylines to anonymous tweets) with a modicum of grace. As John Waters wrote in one of his books, “Sometimes you learn from a bad review. Sometimes they’re right—a little.” There is a difference between not caring what other people have to say—an easy default for avoidant types—and caring without letting it drive you to suicide (or homicide, whichever is more your style).

I’ve been thinking about this because while revisiting one of my favorite DAVIDs recently, I edited it so much that I almost rewrote it. I could still feel how right it felt when I first wrote it, and yet it was all wrong—abandoned themes, twisted logic, affected phrasing, unsatisfying word repetition and, at the same time, the failure to repeat certain words in a pleasing way. Red pen, red pen, red pen. Now it’s much better, but I suspect I love it less. Having fixed it, am I still proud of the original? Will I be proud of this version when I come back to it in three years? Can I be proud of anything I’ve done? I guess what I’m trying to say is that pride motivates me, but that it also doesn’t really matter.

Reminder that I’ll send you a free month of subscriber-only DAVID content if you screenshot your donation to any of the fundraisers featured on Gaza Funds.

Thank you for reading and sharing my weekly newsletter. You can also support me by buying my book. Find me on Twitter and Instagram.

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 55 followers