Davey Davis's Blog, page 10

March 20, 2024

David Davis

A therapist once told me that people are more in touch with their feelings when they’re on their periods. OTR (on the rag), my stepmom called it; her general crudity transcended her very American terror of human sexuality. The therapist, however, was significantly closer to the eat your own placenta on ketamine side of things than my dad’s ugly wife. She was my first healthcare provider who wasn’t completely hostile to transsexuals, so even though her yonic insight was not, you know, the correct way to help a trans person manage their dysphoria, the effort was appreciated. Not that my period gives me dysphoria, as I’d already informed her, but you try convincing a cis person that we’re not as grossed out by ourselves as they think we should be. Still, like the term OTR (one so opaque as to demand explanation, and therefore further engagement with the supposedly taboo topic), her period comment has stayed with me over the years, probably because I—like so many people—am attracted to the idea that there’s a “real” “reason” for the frightening emotions passing through my body.

Other than the inconveniences that plague everyone who menstruates, I don’t mind my period at all. (I’ll puke if I have to hold a purse or speak in a public bathroom, but the bleeding is fine, for some reason.) In fact, it makes me feel feminine in a way I enjoy, but lately that hasn’t been enough to outweigh the PMS symptoms, which are relatively new. Or maybe I’ve always gotten them, but didn’t notice before I was on hormones, since I wasn’t in the business of noticing anything back then. Or maybe they’ve just gotten worse with age—my sibling told me that’s what happens if you don’t have a baby, until menopause, anyway. I’ve already been through menopause (in the sense that my periods stopped for a calendar year), and plan to undergo it a second time because I’ve recently upped my dose again, in part because of this whole PMS thing, which is bad, if abbreviated (I don’t know how long it was for my dad’s now-postmenopausal wife because she was a bitch every day that I knew her, so who’s to say?). I would love to believe, like that therapist, that the paranoia, irritability, and Cathyesque emotional fragility (Ack!) all serve a biological purpose, or signal a cosmic rent in the pearly veil between our world and Theirs, or could at least come with some kind of silver lining. But I don’t think they do. I think we all just have sex hormones interacting with dozens of other hormones and that these interactions make us feel better or worse depending on who and when and where we are, and the rest is drag.

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

March 17, 2024

David Davis 46, part 4

Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3.

When Federico Fellini said he made films because he liked to tell lies, I felt that. In fact, my passion for lying is one my reasons for writing. What are both if not attempts to control information? Like lying, writing is an expression of my desire to be so thorough, so precise, in my communication that I might never be misunderstood (except when it suits me, of course). As a writer, I’m suspicious of words. While there is no enmity between us, there is a tension. Liars know (do writers?) that nothing that is said can ever really be trusted.

Though it’s probably not what a therapist would call healthy, my suspicion of words is great for navigating intimate relationships, particularly the romantic ones: I don’t care what you say, only what you do. Talk is cheap and action is dear; if there is an honest, trusting relationship to be found, it hides in their convergence, like glitter in the gutter of a book.

When I started dating D last year, I noticed that what he said always matched what he did. He said he wanted to buy me things, and he did. He said he wanted to take me places, and he did. He said he wanted to chain me in a basement and observe me from a monitor, and had there been a basement available, I think he would have. In contrast to my inconstancy, D was easily affectionate, paying me outrageous compliments and listening intently when I spoke. When he said he cared for me, I believed him because there was invariably some action to back up the words.

But something was off. “Love bombing” would ascribe to D a sinister intent he didn’t have, and yet everything with him was too much, too fast. I was the one who always had to hit the brakes, say no, go limp. It’s a lot for anyone, especially the relationship’s designated punching bag. When my signals and road flares didn’t slow the momentum, I soft-launched a breakup before we were even properly dating. That was when D unfurled the red bunting I needed: i don’t care if it’s not good for you, he texted. i just want to be with you.

On Jade’s sage advice, I told D I needed a week to think. By the end of the first day of no-contact, I not only knew that it was over, but that I wanted it to be. To blame D for his intensity would be unfair—I know what kind of codependent I am, especially with sadists—but if what he said always matched what he did, then what action might accompany words like i don’t care if it’s not good for you? Even if they had been uttered in a moment of thoughtlessness, there was nothing to be gained by sticking around to find out.

What I did gain from dating D was a reminder, if not a lesson: care happens in both word and deed, even if the liar in me would prefer otherwise. Which brings me to the topic of this installment of my guide for vetting SDATs:

Safer sadists, dominants, and tops demonstrate care for your physical, mental, and emotional safety.

March 9, 2024

David Davis 46, part 3

Lately, I’ve been thinking about pickup play—that is, BDSM1 with someone you have have just met, likely in a cruisey or party environment. For me, pickup play has lived in parallel with anonymous sex, erotic social practices only distinguished by the details. As I’ve been writing this series, however, I’ve begun to reconsider.

In terms of risk profile, a gay bar bathroom blowie with a stranger is different from play party needles with a stranger, which is itself very—if not constitutionally—different from an isolated rope suspension with a stranger with whom you don’t have mutual friends. In any of these situations, you may not know the person you’re hooking up with, but any associated people, places, and communities that you do know will inflect your supposed anonymity, and theirs, too. Which got me thinking: if both anonymous sex and pickup play are contextual and multivalent, then perhaps it doesn’t make sense to apply the same understanding of anonymity when comparing sex and BDSM.

No one told me I had to make this conflation, but it’s easy to do when our culture conceptualizes BDSM as a subcategory; as a stopping point on a sexual spectrum organized, at least on one axis, from least to most normatively violent2. But I don’t experience sadomasochism as a subcategory, though I’m sure plenty do. Even if I did, to project that beyond myself would be to reinscribe the sexual norms that pathologize leathersex in the first place. “Kinky” sex is as normal (read: common) as so-called vanilla sex, but only one of these two things has been normalized to the point of naturalization. My conflation was derived from these norms, and like all of normalcy’s derivatives, it fell apart upon closer inspection.

As someone with an interest in sexual risk management, I used to resist criticizing the safety of pickup play because I was worried I would also have to criticize the safety of anonymous sex. But then I realized: it’s apples and oranges, baby. To that end, I’d like to suggest that what we mean when we say risk profile changes when we reach a certain level of intensity in recreational play, because in a heavy scene trust is everything—and you can’t trust someone you don’t know3. If anonymous sex is a trust fall from a few feet, anonymous power exchange is a trust fall you need an elevator for4.

What all this means, I guess, is that I’m coming out as someone who thinks it’s a good idea to get to know someone before engaging in heavy play (even if such a position is only controversial to me). But how? Well, by playing at a lower intensity, of course, but also by communicating in other ways, like vetting.

Which brings me to the topic of this post! (Wow, David, way to bury the lede.) For this installment of the series, we’ll be talking about what vetting actually is, and who does it, and how.

Why? Because safer sadists, dominants, and tops don’t mind being vetted—in fact, they like it!

March 5, 2024

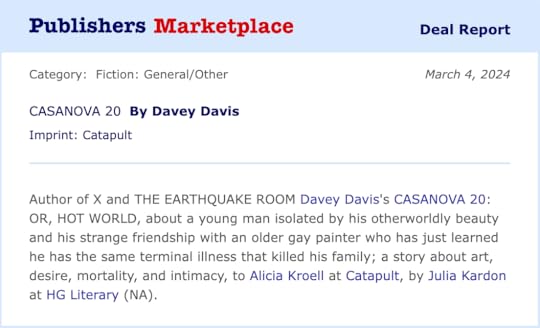

Introducing "Casanova 20: Or, Hot World"

I’m excited to announce that the MS is now complete and preparing for her close-up! With the help of the masterful Alicia Kroell—who edited X, my second novel, to my great satisfaction—I’m optimistic that it will be published sometime next year.

Readers may remember that I shared an excerpt from Casanova, the story of the most beautiful man in the world and the friends he makes along the way, last autumn. For an even more condensed preview, here’s the PM announcement:

I wish it were already 2025 (or do I??). Until then, stay tuned for more updates.

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

March 4, 2024

David Davis

Losing Ground (1982)

Kathleen Collins’ semiautobiographical drama is a gorgeous indulgence: art about art made by artists in love. Sara (Seret Scott), a philosophy professor whose marmish glasses belie latent passions, is annoyed when her husband, Victor (Bill Gunn), a painter with the aesthete’s entitled appreciation for beautiful women, disrupts her study of “ecstatic experiences” when he whisks them to a Nyack rental for the summer.

To say that Losing Ground is a love triangle (or quadrangle, as it becomes when horror icon Duane Jones, whose interest in Sara is her rebuttal to Victor’s wandering eye, turns up) goes a way toward describing the plot, but still fails to capture the vibe. Losing Ground’s melancholy never devolves to tragedy; its dreaminess never loses focus. Collins’ cool, confident direction is thrillingly original, especially its fourth wall-breaking machinations in the student film that Sara joins as her own attempt at the Art that her husband holds in such high esteem.

What I love about Losing Ground is that there is never the feeling that something is lurking around the corner; that our heroine will be lost to bitterness; that Victor’s maddening charisma (I dare you not to fall for Gunn) will win out over Scott’s almost affected earnestness (perhaps it would be better to call it a stylized authenticity). The overall emotional effect is that of a romcom—in that I felt safe—that is also, somehow, painterly!

I’ll be thinking about this one for a long time.

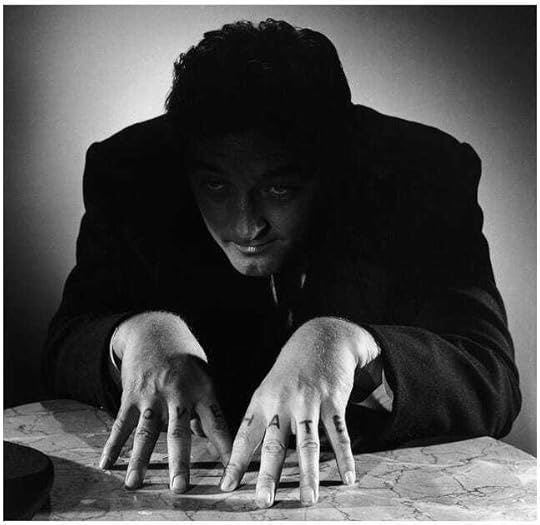

Secretary (2002)

When I was a freshman in college, I was accidentally accepted into a writing workshop for upperclassmen. “Oh,” said the professor, glancing up from the attendance sheet. “You’re not supposed to be here.” I was afraid of him—he was always stoned, or seemed to be, and never said anything that made sense—but he didn’t kick me out.

I can’t remember if I had applied to the workshop out of cockiness or ignorance. This was around the time I experienced my first psychotic episode, so I can’t remember much else, either, other than that I felt a deep disappointment in the quality of everyone’s work, including my own. I do, however, remember this: after class one day, the professor handed me a copy of Mary Gaitskill’s short story collection, Bad Behavior. “I think you might like it,” he predicted.

He was right. The collection famously includes “Secretary,” the story upon which Steven Shainberg’s much bubblier Secretary, which I saw not long after, is based. Lee (a vulnerably plucky Maggie Gyllenhaal), who has just graduated from in-patient for a self-harm problem, is struggling to adjust to life outside when she gets a job as a legal secretary for the strange and demanding E. Edward Grey (a perfectly monotonous James Spader). As they begin to recognize a shared affinity for a more adversarial kind of romance, Secretary skips adeptly through all the necessary cliches: old flames, cold feet, girl power. I don’t think it’s a spoiler to report that, like any good romcom, its ending is a happy one.

Along with a lot of solid characterization, set design, and acting, Secretary embraces the silliness of D/s as part and parcel of, rather than distinct from, the whole romantic enterprise. What results is an original yet true take on the genre, one that—despite the aught’s-era tweeness, goofy soundtrack, and heterosexist (even for a romcom) shortcomings—more or less holds up, which I knew for sure when Lee and Grey’s first negotiation moved me to tears, as it did when I watched it in my early twenties.

But time, of course, has enriched this scene for me. When I was younger, I thought my emotion had been stirred by Grey’s promise to Lee that he could disappear her masochistic compulsions if only she would be obedient to him (a proposition to which she agrees with delight). Now I understand that it’s not absolution that Lee has found in Grey, but connection. As she later says of him, “I feel more than I’ve ever felt, and I’ve found someone to feel with.”

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

February 23, 2024

David Davis 46, part 2

Read the introduction to this series here.

When I began using gay hookup apps a few years ago, I traveled almost exclusively. Deciding that the greater risk was in a strange man knowing my address, I rarely invited hookups my place, where I live alone. “I don’t want them in my apartment!” I told a trans friend. He’d been using the apps longer than I, and assured me, laughing, that I would soon change my mind.

My friend was right. As I gradually began to entertain gentlemen callers, I noticed that many arrived with the telltale signs of nerves. Even the biggest, strongest, butchest guys could exhibit a caution that verged on rudeness. You know how men are; I’m sure some envisioned themselves CoD heroes, scanning the perimeter for insurgents. To me, they recalled flop-eared pedigrees, suspiciously sniffing every piss-stained angle of an urban tree.

But that’s not quite fair. Though there were other reasons for my hookups to be nervous—my gender among them—I recognized their anxiety because I feel it myself every time I darken a new date’s doorway1. Rejoining MSM culture, this time as a transsexual, was a reminder that cis men could be vulnerable too, no matter how disadvantaged I felt myself to be in comparison.

This anecdote is about (more or less) vanilla sex, but I think it illustrates a phenomenon that a lot of us overlook in SM contexts: just because someone has more power doesn’t mean they have all of it. Whether the differential is “real” (that is, based on material conditions like physical strength, or the less tangible, but no less substantial, pressures of our social organization) or negotiated, trust must be earned on both sides—not just on the part of the bottom.

So, my first piece of advice for this series on vetting? Safer sadists, dominants, and tops don’t trust you right away.

February 22, 2024

on Victor I. Cazares

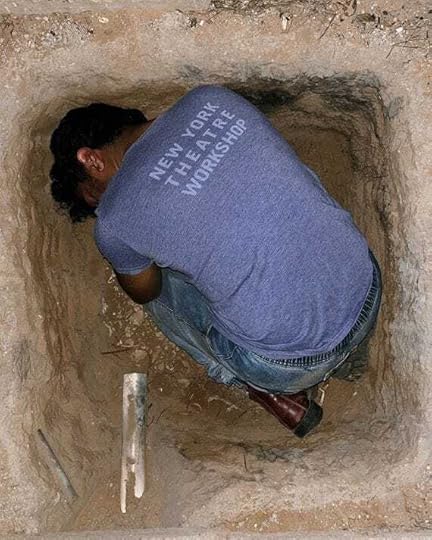

Cazares stages their own burial on Instagram. Photo: Courtesy of Victor Cazares

Cazares stages their own burial on Instagram. Photo: Courtesy of Victor CazaresThis morning, Vulture reported on the HIV medication strike of playwright Victor I. Cazares, who has not taken their Dovato in almost three months. Cazares will continue to deprive themself of this life-saving medication until the New York Theatre Workshop—with which they have been affiliated since 2020—calls for a ceasefire in Gaza.

I urge you to take a few minutes to email anyone and everyone on staff at the NYTW (you can find their contact info here) and urge them to do the right thing. As well as being profoundly moral, Cazares' selflessness is, in my humble opinion, the praxis of art. What an honor to have an artist of this caliber associated with one’s institution!

I hope that our combined emails may contribute to the public pressure that will cause the NYTW to end this strike and the harm it is causing to Cazares, who for the first time since they seroconverted a decade ago is no longer undetectable. Phone calls, boycotting, and other means of applying pressure to the NYTW are of course a great idea as well!

Thank you so much, everyone.

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

February 15, 2024

David Davis 46

What began as a single post has somehow snowballed into a longer project. While this intro is available to everyone, the rest of the series will be paywalled. More to come!

There’s a recent viral Twitter prompt that goes like this: What are 5 topics you can talk about unprepared for 30 minutes? “How to vet tops for sadomasochistic experiences” might be one of mine—not because I’m an authority, but because I’ve fucked up enough, over the years, to have learned a thing or two. To these lessons belong the physical and emotional scars that I feel complicated about (regret being, as it usually is, inadequate).

Now, some of those fuckups weren’t really fuckups at all. They were my best choices under the circumstances, albeit sometimes made in ignorance or while otherwise limited by factors beyond my control. As much as I have tried to ignore or deny it, some of these scars are ones it was not in my power to prevent.

As for the actual fuckups? They were self-harming or self-serving (sometimes both), and led to damage done to me or to someone else; sometimes, that someone else included a particular scar’s perpetrator. I’m not responsible for the harm caused by their malevolence or neglect, but with the benefit of retrospect and the knowledge shared by people wiser than I am, I now understand that I could have substantially reduced my risk profile by exhibiting more care toward myself and those around me. Not all of these scars were inevitable.

I can’t deny that I’m writing this guide for selfish reasons: to better understand why I made certain choices in my past, if only so I can make better ones in the future. But I’m also writing this guide so others can learn from my carelessness. Maybe it will help you avoid complicated scars of your own.

I wish I could channel Wile E. Coyote to deploy a big, red, neon arrow to direct you to the sunny pastures where they keep all the safe sadists and dominants—but I can’t. The “safe sadist/dominant” doesn’t exist, just as the “unsafe sadist/dominant” doesn’t exist. A person who may have once been a walking red flag may now have their shit together; a person who I may have recommended to you a few years ago may now deserve to have their DMs ignored. People change, and regardless of what’s going on inside, we are concerned with behavioral patterns, here, not internal states (This applies to everyone, not just tops1!)

While there is no safe player, there are habits, practices, and beliefs that lead to safer play. In my experience, a person who consistently demonstrates these habits, practices, and beliefs tends to be safer to play with2. Perhaps more importantly, they also tend to be more willing to be accountable for their mistakes3 ; to problem-solve to avoid future mistakes; and to establish and maintain boundaries to protect themselves, as well as the people around them.

Before we get to the guide part of this series—which I’m hoping to publish within the next week—a little housekeeping is in order.

First of all, this guide is not designed for everyone, though everyone is welcome to it. This guide is also not designed to be read without a hefty dose of context and nuance: my North Star here is personal responsibility and community accountability. Partaking in SM means accepting that, even if we do everything right, something still may go wrong. That is the nature of high-octane sex, just as it is skydiving, extreme sports, giving birth, one-night-stands, unregulated drugs, falling in love, signing a contract, getting behind the wheel, and so many other things that are fun, interesting, meaningful, or otherwise worthwhile.

So, without further ado, my notate bene:

This guide operates on the assumption that the reader has foundational knowledge about SM and may even be active in their local leather scene. While I think those with less experience, or those with less of an intention to act on this advice, could also benefit from it, it’s aimed primarily at those who aren’t merely kinky (i.e., they are leather-identified, not weekend warriors), or who don’t need BDSM 101 to first understand what we’re doing here.

Like I said, I’m no authority. I’m not an educator, a teacher, or a leader—and certainly not a sadist or dominant. My credentials are, mainly, my mistakes. If it helps for you to know, for the past decade or so I’ve played both recreationally and professionally and have been involved in my local scenes in the Bay and New York City.

Just as “safe” is not a permanent label, neither are “sadist,” “dominant,” or “top.” The people you’re vetting may disidentify with these labels some or all of the time, but it may still be relevant to them; that’s your call. While I think most, if not all, of my advice can also be applied to be masochists, submissives, and bottoms, this guide was written with people who are looking to have stuff done to them in mind.

I do not believe that the power in the scene is concentrated with the sadist, dominant, or top. Nor do I think it really belongs to the masochist, submissive, or bottom, as some people like to say (this reactionary stance drives me nuts!). Here’s what I think: that SM is people coming together to exchange power in an eroticized way, and that while that exchange can take many different shapes, it aspires to—though can never really attain, IMO—an egalitarian expression of desire among likeminded people. SM is the dramatization of inequality, but while it explicitly names power differentials in a way I don’t see in any other context, it doesn’t take place among social equals, just like vanilla sex, or indeed any other interaction. I play with people of different races, genders, ages, (dis)abilities, economic statuses, etc., and while trying to find an absolute answer to whether one person is more powerful than another tends to devolve into useless “oppression Olympics,” the fact of the matter is that some people are more at risk of me abusing them than vice versa—because I’m white, because I get a W-2 in the mail every year, because I’m not subject to transmisogyny, because because because of an ever-shifting amalgamation of reasons. Abuse is the leveraging of social, legal, and political power to harm someone else, and it is, again IMO, more often than not a crime of opportunity, an (often unconscious or repressed) expression of entitlement reinforced by the culture at large, and ultimately reliant on deep-seated assumptions about what is natural, essential, and inescapable.

I may use sex and play somewhat interchangeably, but this guide is more about play than sexual intercourse (to the extent that these things can be distinguished from each other). By that I mean: while anyone can be harmed during vanilla sex, your risk profile changes when you add sadomasochism to the mix. SM and its associated identities and subcultures are criminalized and/or illegal4, socially stigmatized, and involve what are, essentially, weapons.

Intent matters, until it doesn’t.

My approach to SM is grounded in RACK: it is risk-aware and consensual. These days, some people are also using PRICK (or personal-risk informed and consensual kink) to guide their play. This extra “P” doesn’t really make any sense to me, because I think everyone involved in a given scene should be aware of the risks involved for everyone else, and so I’m sticking with RACK for now.

This guide is only for recreational play. Screening for transactional play partners is a different beast (about which my knowledge is increasingly out-of-date), although there are many aspects of professional vetting that I think might be of use to recreational players5.

So, as I said up top, more to come! In the meantime, if you don’t care about any of this, I’ll still be writing other ad-hoc newsletters and continuing with my other series on sex scenes. Until next time!

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

1I’m often fast and loose with the distinctions between sadist, dominant, and top, but they’re not interchangeable. I broke down the distinction several years ago in a primer I wrote about aftercare for them.

2Safer—never safe. There is no certainty of safety, and to expect as much from recreational violence is not only silly, but unfair to those doing it with you. A quick google revealed a short blog post on the difference between safe and safer sex is a good corollary for what we’re talking about here.

3Daemonumx recently shared this resource on accountability on her Instagram, if you’d like further reading/listening.

4The amount of people who have gotten angry at me on Twitter for acknowledging that SM is assault blows my mind. EYE do not see it as assault—unless we append that word with adjectives like “consensual,” “organized,” “romantic,” “therapeutic,” “sexy,” “risk-informed,” “thrill-seeking,” “spiritual,” etc.—but guess who does? The people who make and enforce the laws! That’s just the reality, people!

5That being said, there are problems with the adoption of sex workers’ tactics for professional safety by civilians, which can become appropriative when used to reinforce the whorephobia that afflicts so-called “sex positive” and even leather spaces (imagine being whorephobic in LEATHER???). Here’s an example that I didn’t make up: on a Discord server for a private sex party, people were asking if attendees would/could be compelled present STI panels before entry. “I’m vetting them for my safety,” was their rationale. Requiring that people prove they don’t have STIs to attend a sex party reinforces all kinds of stigma (and it also doesn’t prevent the transmission of STIs), including the kind that gentrifies leather spaces—which originate in hustler/sex worker cultures—making them more hostile to sex workers. That’s the gist of my argument, one that deserves expanding on. Maybe another time.

February 13, 2024

David Davis

As a kid, I loved the Proust questionnaires in the back of my mom’s Vanity Fair magazines. Most of the articles went over my head, but these deceptively straightforward glimpses into the lives of famous actors, athletes, artists, and other figures were perfect for a young reader.

Believing their subjects’ answers to be both extemporaneous and deeply serious (I’ve always been very literal), the idea of doing one myself seemed entirely overwhelming. Now I understand that it’s all in good fun—not a federal deposition. I’ve always dreamed of assigning them to my friends. Maybe this will get the ball rolling.

David’s Proust QuestionnaireWhat is your idea of perfect happiness?

Overcoming pain

What is your greatest fear?

Pain

What is the trait you most deplore in yourself?

Cowardice

What is the trait you most deplore in others?

Hypocrisy

Which living person do you most admire?

At the moment I am thinking of Dr. Amira Al-Assouli.

What is your greatest extravagance?

Using plastic containers to store food. Living alone. Thriftbooks.com.

What is your current state of mind?

Irritable, but fine

What do you consider the most overrated virtue?

Self-control

On what occasion do you lie?

Frequently, but only rarely about anything of consequence

What do you most dislike about your appearance?

The secret to feeling confident about your appearance is to never disclose what you dislike about it.

Which living person do you most despise?

Genocide Joe is as good an answer as any.

What is the quality you most like in a man?

Strength

What is the quality you most like in a woman?

Whatever makes her feel nice!

Which words or phrases do you most overuse?

At the moment, “It’s developmental!”

What or who is the greatest love of your life?

Jade

When and where were you happiest?

I don’t like to think about this question.

Which talent would you most like to have?

Being able to dance well appears to feel amazing.

If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be?

I have to admit that I often wish that I were healthy.

What do you consider your greatest achievement?

Writing

If you were to die and come back as a person or a thing, what would it be?

Ah, to be a beloved cockatiel living, uncaged, among indulgent bourgeois lesbians.

Where would you most like to live?

Who wouldn’t relish a sturdy cottage on the Southeastern coast of Iceland?

What is your most treasured possession?

I don’t think I treasure possessions that much, though I adore living among my books.

What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery?

Being ill and unshowered and alone and broke while far away from home

What is your favorite occupation?

Writing

What is your most marked characteristic?

Anxiety

What do you most value in your friends?

Conviction, creativity, and calm

Who are your favorite writers?

Vladimir Nabokov, Dennis Cooper, Gayl Jones, Cormac McCarthy, Toni Morrison, John Berger, E.M. Forster, Edith Wharton, Chip Delany

Who is your hero of fiction?

Hannibal Lecter

Which historical figure do you most identify with?

Gary Indiana is still living, but recently I’ve begun to feel strongly that we are the same person.

Who are your heroes in real life?

People who take care of other people and animals even when it would be easier not to

What are your favorite names?

I love my own name, actually.

What is it that you most dislike?

God, where do I start? I take it personally when city people don’t train their goddamn dogs.

What is your greatest regret?

Probably going to college

How would you like to die?

Quickly, painlessly, and unexpectedly

What is your motto?

“There’s no accounting for taste.”

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

February 6, 2024

David Davis 45, part 2

My idea of heaven is to be hunting with you in some beautiful park with mountains like here at home but where we wont need guns or prey but we will just walk together arm in arm in this good world and be by ourselves always together forever and a day.

—Brian McFee’s letter to his lover and murderer, Sidney de Lakes

Be forewarned: even by 2024 standards, James Purdy’s Narrow Rooms, published in 1978, is as hard to stomach as it is easy to read. The above excerpt—which recalls E.M. Forster’s mythic greenwood, where Englishmen in love might escape the constraints of homophobic “civilization”—only hints at the violence in which the majority of the novel rolls like a dying pig in hot mud. Whereas Rooms’ depictions of homosexual sex (where consensual) have been tempered by time, its rape, murder, and general brutality are as challenging as ever. There’s even a crucifixion, all the more heretical for making Christ’s look like a walk in Brian’s beautiful, mountainous park.

As I wrote a few weeks ago, Rooms was recommended to me by my friend, Daemonumx, who raved about its violent, sodomitical romance. I was surprised, only familiar with the Purdy who was a “gentle naturalist” of “small-town American life,” as Susan Sontag described him1. It turned out there were other Purdys, and the one who wrote Rooms was, per Sontag, the “writer of vignettes or sketches which give us a horrifying snapshot image of helpless people destroying each other.”

In the case of Rooms, these “snapshot images” coalesce into the story of four young Appalachian queers: Sidney de Lakes, football hero turned murderer who has returned home after serving time; Brian McFee, the boy he loved and killed; Gareth, the invalid son of a wealthy widow; and Roy Sturtevant, known as the Renderer, whose sadistic obsession with Sidney was spawned deep in their shared boyhood. What results is a pulpy, queeny, almost eldritch love triangle set in a gothic country noir2.

What I love about Rooms is that while (or perhaps because) its violence is atmospheric, it’s not always possible to discern which of it is good and which bad. By “good” and “bad” I mean, I suppose (though not even this is without reservation), consensual. In Rooms, sexual consent, or lack thereof, is constantly problematized—by the characters’ conflicted desires, by their muddled senses of obligation or ethics, by authorial appeals to the biblical, the magical, or the predestined. In leather culture, we rely on a sturdy, if not infallible, consent framework to help us stake out the line dividing hurt and harm. Rooms, while mostly peopled with homosexual men, takes place in a context outside and away from identity-based movements and subcultures like gay liberation and leather, to the extent that they can be teased apart. There is no sense that this small group of people in rural West Virginia is invested, or even aware, of these things3. They’re not doing S&M, or even homosexuality. They’re doing something else.

While the plot of Rooms is unambiguously sexual and violent, parsing it is complicated by this slippage4. When is it sexual violence and when is it violent sex? How do we differentiate between sex and violence (see Mitchum’s knuckles) at all? What even constitutes a sex scene in a book where guns are romantic; rusty nails flirtatious; sodomy ordained by god? To revisit Brian’s letter to Sidney, what is hunting without guns or prey?

But if we eschew the philistine’s dictum that sex scenes are only acceptable when “advancing the plot,” we don’t need to answer any of these questions (not for the philistines’ ugly purposes, anyway)5! You guys, the plot is not some separate entity whose integrity must be protected from the story, the book itself, or the reader! God didn’t come down from heaven to say that any kind of scene must drive the plot, although of course how the novelist navigates this relationship will say a lot about whether their book is interesting, entertaining, transcendent, or something else.

The fact of the matter is that Rooms does not exist without so-called sex scenes, no matter how stringently defined or censoriously punished. As Paul Binding writes in the introduction of the 1985 edition Daemonumx loaned me:

Because [Rooms] could not work on us unless we were made to share the emotional and sexual experiences of the central characters, Purdy insists that we have access to scenes of the utmost intimacy.

Indeed, to lose Rooms’ scenes of “jubilant entry into anus, single and double fellatio…” would be like being “excluded from the exchanges of Heathcliff and Cathy”—protagonists of another geographically isolated, topographically wild, incestuously passionate love story whose racism/racialization is both text and sub-, but whose lovemaking is at least considered natural. No, were this to happen to Rooms, Binding writes, “The metaphysics of the novel, as well as the particular psychological predicament, would be invalidated.”

For these reasons, Binding goes on, Rooms “constitutes a new landmark in the serious and poetic treatment of homosexual behavior”6. Almost fifty years since the novel’s publication, I think that landmark retains its gravity. What’s more, Binding declares that a serious engagement with (the) homosexual (in) art actually requires the sex scene, at least in this case. Denying “…Purdy’s courageous and uncompromising acceptance of the far from comfortable truth that passion is the most important constituent of the universe, and confounds all intellectual attempts to define or contain it, is to pervert a creative force into a destructive one.”

Read Part 1 of this series on the sex scene.

Find me on Twitter and Instagram. Get my second novel, X, right here. Learn more about the history of this newsletter here.

1Often mistaken as black and often by white writers of note—perhaps because of the influences that the Harlem Renaissance and jazz had on his writing, perhaps because his black characters tended to be imbued with an unexpected quantum of humanity—the white Purdy was reportedly an antisemite of some conviction, despite his having written often about “outsiders—women, African Americans, gay people, Native Americans.” In the more recent writing about him that I’ve found, the former is highlighted and the latter downplayed. I’m reminded of Patricia Highsmith, another white gay author whose, uh, peccadilloes have often been overlooked in light of her sexual marginalization. At any rate, as the twentieth century waned, Purdy rejected the increasingly benign designation of “gay writer”: “I’m a monster. Gay writers are too conservative.”

2This Amazon review, titled “When Bad Boys Feel Their Oats,” is a good, spoiler-filled summary if you’d like to know more about Rooms’ plot.

3“Our little mountain town here, in remote West Virginia, has had its veil torn away, and there have been revealed things just as terrible as those we read about in great seaports and immense metropolises the world over.”

4Back to Forster, whose Aspects of the Novel describes plot this way:

5We have defined a story as a narrative of events arranged in their time-sequence. A plot is also a narrative of events, the emphasis falling on causality. “The king died and then the queen died,” is a story. “The king died, and then the queen died of grief,” is a plot…If it is in a story we say “and then?” If it is in a plot we ask “why?” That is the fundamental difference between these two aspects of the novel. A plot cannot be told to a gaping audience of cave men or to a tyrannical sultan or to their modern descendant the movie-public. They can only be kept awake by “and then—and then——”

Where does this “advancing the plot” thing come from? Twitter, naturally! Sorry, all the quality content in this newsletter is paywalled.

6I can’t apologize for quoting Binding at length here. His analysis is better and clearer than mine, and so on the nose, in my opinion, that there’s little I can do to improve upon it. I’d never heard of him before reading this book but his intro slaps!

Davey Davis's Blog

- Davey Davis's profile

- 55 followers