Michelle Cox's Blog, page 21

March 26, 2020

“My Angel”

Theresa Svoboda was born on March 23, 1911 in Chicago to Frank and Simona Svoboda, both of whom were immigrants from Czechoslovakia. According to Theresa, her father came alone to the United States looking for work and found a job right away, which he considered lucky, as jobs were scarce. He began working as a sort of blacksmith and did ornamental work with iron. He made beautiful and intricately-detailed iron fences. Having gotten a job, he immediately sent for Simona to join him. Together they had two children, Theresa and Bernard.

Theresa Svoboda was born on March 23, 1911 in Chicago to Frank and Simona Svoboda, both of whom were immigrants from Czechoslovakia. According to Theresa, her father came alone to the United States looking for work and found a job right away, which he considered lucky, as jobs were scarce. He began working as a sort of blacksmith and did ornamental work with iron. He made beautiful and intricately-detailed iron fences. Having gotten a job, he immediately sent for Simona to join him. Together they had two children, Theresa and Bernard.

Theresa went to school through the eighth grade and attended one year of high school before she quit. She claims that there was “too much fooling around,” so she enrolled in a business college instead. When she graduated, she began working in an office and stayed there for eleven and a half years. After that she moved from office to office over the years and says that she enjoyed all of her jobs.

Theresa never married. She says that she had some nice boyfriends, but none of them stood out as being really special. Nor did she want to get married just to be married. Besides that, she didn’t want to leave her parents “in the lurch,” especially because the economy was so bad. She felt that it was her duty, since she had a good job in an office, to stay and help support them. Theresa lived with her parents in their two-flat on Christina Avenue until 1955, when her parents both died within six weeks of each other. Her father died of a “bad toe.” Apparently it got infected somehow and turned “dark as a plum,” and he eventually died. Simona died six weeks later, though Theresa is not sure of what. Five years after that, her brother Bernard died as well.

Not much else of Theresa Svoboda is known. What happened from that moment in 1960 when her brother died to her present admission to a nursing home is not entirely clear. Apparently, she continued to live in the two-flat on her own, but as the neighborhood got worse and worse, Theresa became more and more reclusive. She was robbed at least twice, and the first floor apartment was left empty and was eventually gutted, presumably by neighborhood gangs.

About five years ago, in 1989, Theresa suffered from frost-bite and had to have several toes amputated as a result. The story made the newspaper, and after reading the article about Theresa’s plight, a woman by the name of Sissie Novak decided to take action. She began a correspondence with Theresa and sent her many packages with clothes, blankets, food and personal items.

Recently, however, Sissie stopped receiving return letters from Theresa, which worried her. Theresa was not in the habit of writing often to Sissie, but she would at least send a thank you note after receiving a package. When the notes stopped coming, Sissie sent a postcard, urging Theresa to respond to let her know she was okay, as Sissie had no other way of contacting Theresa, who did not own a telephone. When she still did not hear from Theresa, Sissie finally decided to call the police. The police eventually followed up on the call, but Theresa refused to open the door, fearing a trick. The police then urged her to go to the window and look out, where she could see their squad car, uniforms and badges. Reluctantly, then, she opened the door.

Upon entering her apartment, the police discovered that she was living there with no heat and no utilities and that her only source of food was apparently a nearby McDonalds. Her legs were severely frost bit, and she could barely walk. The officers attempted to get her to leave with them, but she refused. They left and reported their findings to Sissie, who, because of her own health issues, could not drive into the city to aid Theresa herself. Sissie continued to repeatedly call the police, begging them to periodically go and check on Theresa. Finally, one officer took it upon himself to try to help Theresa. He went back to the apartment on his own time and managed to coax her out and then drove her to Methodist Hospital, where she eventually had to have both legs removed.

Meanwhile, Sissie stayed in contact with the hospital and when it was time for Theresa to be discharged to a nursing home, she urged the staff to place her in a Czech home where she hoped Theresa would get not only a warm bed and good food, but a fellow community she might be able to relate to.

As soon as Sissie was physically able to drive to the city, she met up with the officer who had taken Theresa to the hospital, and the two of them went to the two-flat to see if there was anything salvageable or anything Theresa might want or need at the nursing home. When Sissie arrived there, it was worse than she had ever imagined. It was filthy, wretched and freezing. Gang graffiti covered the inside walls, and it appeared to be little more than a wind break from the elements. But what surprised Sissie the most, however, was that all of the packages she had sent over the years with food, blankets, clothing —even a space heater—were stacked up in the corner, unopened.

As for Theresa, she says she is “content” with her current placement in the nursing home, though she seems muted and depressed. Nothing seems to bring her either joy or sadness. She expresses no concern or worry about anything at all, to the point of complete indifference. She doesn’t believe in planning ahead, she says, “because you never know what’s going to happen.”

Sissie visits whenever she can, though she lives in the far suburbs, so it is a bit of a trek for her. She says that she was angry when she discovered that Theresa had not used a single thing she had sent to her, but, upon learning Theresa’s history, she eventually came to the conclusion that the relatively sudden deaths of all of Theresa’s family members “must have drove her a little crazy.” Likewise, Sissie says she thought Theresa would be more grateful to her for rescuing her, but Theresa does not seem to understand that it was Sissie who was responsible for getting the police to intervene. Theresa does, however, seem to realize that it was Sissie who sent her all the packages and calls her “my angel,” whenever she visits.

(Originally written February 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “My Angel” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 19, 2020

“Winnie Didn’t Lead That Kind of Life…”

Loretta Coleman was born on April 22, 1936 in Louisiana to Frank Harris and Ruth Roberts. Not much is known about Loretta’s parents, but she says that she and her three siblings had a good childhood and that they were raised in a very strict Baptist household. Loretta graduated from high school and was then sent to live with relatives in Chicago, where she got a job as a cook in a cafeteria.

Loretta Coleman was born on April 22, 1936 in Louisiana to Frank Harris and Ruth Roberts. Not much is known about Loretta’s parents, but she says that she and her three siblings had a good childhood and that they were raised in a very strict Baptist household. Loretta graduated from high school and was then sent to live with relatives in Chicago, where she got a job as a cook in a cafeteria.

At some point, Loretta was introduced to Roy Coleman, who worked at a meat packing house. They began dating and eventually married. Once she got pregnant with their first child, Leroy, Loretta quit her job at the cafeteria and stayed at home to take care of him. She and Roy had a total of seven children (Leroy, Charles, LaVergne, Franklin, Mattie, Abraham, and Winnie) before they finally ended up divorcing. After that happened, Loretta was forced to go back to work as a cook, so the children had to fend for themselves while she was gone. Loretta says that she later learned that Roy had passed away, but she is not sure of what. She says that they were close in the early days of their marriage but that they drifted apart as time went on, especially when he started to stay out late, going to bars and picking up other women.

While that period in her life was difficult to get through, her biggest tragedy was yet to come when her youngest daughter, Winnie, was murdered at age twenty-four. Loretta says that Winnie had had a baby, Marcus, out of wedlock but was estranged from the father, Dean Richards. Winnie apparently led a simple life at home with Loretta, which makes her death all the harder for Loretta to accept, because, she says, “Winnie didn’t lead that kind of life.” Loretta describes Winnie as a quiet, good girl who worked two jobs to support herself and Marcus and who sang in their church choir. She was “a very good person,” Mattie says, and she still cries about Winnie’s death, which occurred just two years ago.

When asked what happened to Winnie, Mattie relates that for some reason, Winnie agreed to meet up with Dean one night and left Marcus, then just one year old, with Loretta for the evening. When Winnie didn’t come home, Loretta called the police, who later found Winnie’s body in a hotel room, where she had been shot to death. The police eventually picked up Dean and held him for a time, but they did not have enough evidence to convict him. In Loretta’s mind, however, he is guilty of murdering her Winnie.

Following Winnie’s death, the care of Marcus fell to Loretta. Though she loved him completely, she did not think she could raise another child, especially with her own health issues, so she decided to give Marcus to her younger sister, Agnes, who was living in California. Loretta says that it almost killed her to give up Marcus, since he was a part of Winnie, but she knew she couldn’t give him what he needed and that it was for the best. After he was gone, Loretta then went through a grieving period for both Winnie and Marcus. She often describes how during those many months, she would wake up each day, happy, but then would remember the tragedy all over again and be thrown into a fresh depression and despair. To make matters worse, Loretta’s son, Franklin, who was also living with her at the time of Winnie’s death, began drinking heavily as a way to deal with his grief over his sister’s death and quickly became an alcoholic.

Loretta eventually sought the professional help of a counselor, whom, she says, helped her immensely, as did prayer. She continues to urge Franklin—and all of her other children—to seek help, as well, to aid them in coming to terms with Winnie’s violent death, but she has had varying degrees of success in getting any of them to go.

Loretta says she takes one day at a time. She attempts to go on as best she can and tries to keep Winnie alive by remembering the funny things she did and the good times they had together. She also tries as hard as she can to keep in touch with her grandson, Marcus, so that he will remember his family in Chicago, but it is difficult. Tending to her many plants, decorating, and going to bingo and coffee shops are all things that have helped her to cope these last two years.

Recently, however, Loretta has had to have her toes on her right foot amputated and was thus admitted to a nursing home to recover. Franklin and her daughter, Mattie, visit her frequently. Both are anxious for their mother to come home. Loretta does not open up easily and seems reluctant to share all of her story. She is a very private person and does not interact much with the other residents, who are all significantly older than she. She spends her day doing crossword puzzles, reading the Bible, talking on the phone or watching TV, biding her time until she can return to her home. She is a calm, patient woman, who will answer questions politely, but she tends to direct every conversation back to the topic of her murdered daughter. “Why did this have to happen?” she often asks. “What is the point of it all?”

(Originally written March 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Winnie Didn’t Lead That Kind of Life…” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 12, 2020

The Ultimate Romantic

Jan Beranek was born on December 21, 1909 in Slovakia to Kornel Beranek and Hedvika Klimy. Jan’s father, Kornel, worked as a very successful tailor. He had large accounts and employed six to eight men at any given time. When the WWI broke out, however, Kornel was forced to dissolve his tailor shop to become a soldier. He wasn’t away at the war for long, though, before he became deathly ill and was discharged home. Kornel spent a long time recovering and then began a concrete company, which was even more successful than the tailoring business. In total, he employed fifteen to twenty men, and the Beraneks were considered fairly well-off.

Jan Beranek was born on December 21, 1909 in Slovakia to Kornel Beranek and Hedvika Klimy. Jan’s father, Kornel, worked as a very successful tailor. He had large accounts and employed six to eight men at any given time. When the WWI broke out, however, Kornel was forced to dissolve his tailor shop to become a soldier. He wasn’t away at the war for long, though, before he became deathly ill and was discharged home. Kornel spent a long time recovering and then began a concrete company, which was even more successful than the tailoring business. In total, he employed fifteen to twenty men, and the Beraneks were considered fairly well-off.

Jan’s mother, Hedvika, stayed at home with their six children. She was apparently very intelligent and had been partially educated. Her two brothers had studied to become teachers, and Hedvika was just a year into her studies to become a teacher, as well, when her father died. Hedvika had no choice, then, but to quit so that she could help her mother with her four younger sisters.

Education remained very important to Hedvika, however, as it was with Kornel, so all of their six children were sent to school beyond the grammar school level. All three of Jan’s sisters went to high school and three years of “industrial school,” where they studied “domestic science.” Jan went to high school and then to four years at a business academy to study accounting. In the middle of his training, though, when Jan was just sixteen, Kornel died. Jan says that his father’s death had a profound effect on him and that he still remembers him with great fondness.

Jan’s first job out of school was working as a bookkeeper for a man whose business was to “buy and sell goods.” Jan was so efficient that after only a couple of months, the man ran out of work for him to do and thus laid him off. From there, Jan’s brother-in-law, an engineer, got him a job in a building company, where Jan worked as a timekeeper, a bookkeeper and an assistant surveyor for over eight years.

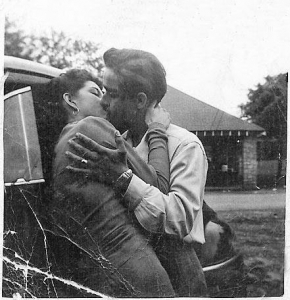

It was during this time that Jan met the love of his life. He was twenty-five years old.

He tells the story as follows: On a warm April day in 1935, Jan got the urge to be outdoors instead of in his stuffy office. He snuck away from his desk at lunch time and decided to go walking in the fields. Unable to resist, he laid down in the fresh grass for a quick nap and soon fell into a deep sleep. He didn’t wake up until 1:30 p.m. – well past his lunch hour; whereupon, he jumped up and rushed back to work. Luckily, he did not get in trouble, but he developed a terrible cold from lying so long on the damp ground. The cold persisted for several weeks, so he finally asked permission to leave work to go to a doctor and, upon getting his boss’s approval, took the streetcar into town.

At the doctor’s office, there were about five people waiting ahead of him. As Jan took his place in line, he saw before him a lovely young girl, idly twirling a French hat. When she dropped it, Jan bent over and picked it up and handed it back to her. From there they began talking, and Jan learned that her name was Amalie Laska and that she lived with her uncle, a retired train officer, in town.

Finally Amalie was called in to see the doctor, was examined, and then left, waving goodbye to Jan as she went. Jan then raced into the doctor’s office and began to ask him for any information on Amalie. As it happened, Amalie’s brother and the doctor had gone to school together and were very good friends, so he knew all about Amalie. He didn’t think it right, however, to give Jan her address.

When Jan finally left the doctor’s office, wondering how he could see Amalie again, he found to his surprise that she was standing in the vestibule of the building, trying to avoid the rain that was pouring down. Jan was delighted to see her, but she turned and reproached him, saying, “Don’t think I waited here for you!”

Rather than be deterred by her comment, however, Jan thought she was even more delightful than he did before. He offered to help her onto the streetcar, but she vehemently declined, saying that she did not have the money for the streetcar, and likewise refused to let him pay for her. Thinking quickly, Jan left her for a moment and rushed out into the rain to a nearby shop and bought her a box of chocolates.

When he arrived back in the vestibule, soaked, and handed her the chocolates, she seemed angry at first but then politely accepted them. The rain let up, then, and they parted, Amalie refusing any help from him. Sadly, he caught the streetcar back to work, and Amalie walked home, where she hid the chocolates under her pillow so that her uncle, who was extremely strict, wouldn’t see them.

Jan was utterly surprised, then, when upon walking home from his streetcar stop, he happened to look up at a house he was passing and saw Amalie in the window! It was a house very near his sister and brother-in-law’s home, where he was currently living. He couldn’t believe his good fortune! He waved, and to his delight, she waved back.

Because Amalie’s uncle did not approve of her dating anyone at all, she and Jan developed an elaborate set of hand signals to give to each other while he stood in the street beneath her window. This went on for many weeks until one day when Amalie’s uncle happened to notice Jan in the street making his strange hand gestures. Amalie’s uncle feared Jan was an insane lunatic and that he was perhaps attempting to intimidate the elderly neighbor woman who lived above them. Upon closer inspection, however, he realized he was gesturing to Amalie and was furious!

That was the end of Jan and Amalie’s secret relationship. Jan was hauled into the house and properly introduced and, to the uncle’s surprise and pleasure, then accompanied them to church! As time went on, Amalie’s uncle’s stiff exterior began to melt a little, and he eventually grew to like and approve of Jan.

Jan proposed to Amalie on a Sunday—July 10th, 1935, which happened to be her name-day. They took the streetcar out into the country for a picnic. Jan brought flowers and chocolates, and they sat by a creek and had a picnic lunch. Jan then asked her to marry him. She accepted, but she cried because she had nothing to offer him. Jan, needless to say, did not care, so overjoyed was he that she was to be his wife.

They were married on April 4, 1936 at 4:00 pm. At first, Amalie’s uncle was not crazy about them marrying so young, but when the couple assured him that he could live with them, he rapidly gave his approval. At the last minute, however, he changed his mind and went to live with his sister instead.

Soon after their marriage, Jan decided that he wasn’t being promoted fast enough in the building department where he worked, so they decided to move to Prague, where he got a job with the city sewer department as a surveyor. While there, a friend asked him if he wanted to work part-time for the city newspaper. Jan agreed and soon liked it so much that he began working there full time. He advanced quickly and was soon the administrator of the whole newspaper by 1945.

Meanwhile, Amalie found work as a seamstress until their daughter Klara was born on August 15, 1939. Jan simply adored his baby daughter. He took her for walks in her buggy every Saturday, and the three of them were very happy. When she was only five years old, however, Klara came down with diphtheria and died. For Jan, it was the most tragic thing that had ever happened, or ever would happen, to him in his life. Unfortunately, he and Amalie did not have any more children, as the doctor warned them that it would put Amalie in mortal danger. Also, they were unwilling to bring another child into the world when their lives were so uncertain due to the WWII and the political unrest around them.

Somehow, Jan and Amalie survived their personal tragedy and the war years as well, but in 1948, Stalin began rounding up all of the intellectuals and leading men of the country. Jan, as head of a major newspaper, was targeted, so Jan and Amalie decided to flee. They made their way to an international refugee camp in Germany, where they stayed three months. From there, they were transferred to a camp in Italy for a year and a half. They wanted desperately to immigrate to America, but the waiting list was over two years. Meanwhile, the conditions in the camp were terrible, and Amalie was sick. They decided, then, to go to Australia instead.

A friend they had met in the camp went with them, and once in Australia, Jan found a job with the government, laying electrical lines. Amalie was able to again find work as a seamstress. When Jan’s two-year contract was up for that particular job, they moved to Malvern, where Jan worked for an English factory that made jam. While there, Jan met a man named Mr. Gregory, who befriended him and invited him to see the observatory where he worked.

The Americans had built an observatory near Malvern, where periscopes for submarines, among other things, were built. The observatory also contained a 30-meter telescope, which was under the strict control of Greenwich, England. It was in a very secluded place in a forest on a hill, and Jan was fascinated by the work that went on there. He spent a lot of his extra time at the observatory and even volunteered some of his surveying skills when needed.

Eventually he managed to persuade Mr. Gregory to let him look through the telescope, which was off limits to all personnel. So one night, the two men snuck back to the observatory, unlocked the telescope and beheld the night sky. Jan was in awe. For him, it remains the most beautiful sight he has ever seen.

As a whole, however, Jan and Amalie did not like Australia, so in 1956, they left for Canada. They stayed there only a year and a half, however, as Jan could not find work. They were living only on what Amalie could make as a seamstress, so they decided to go back to Australia. When they got there, however, they found that things had changed a lot in their short absence, or so it seemed to them. Unemployment was high, and they found it difficult to make ends meet.

So, once again they decided to leave. It was 1960, and they were finally accepted into the United States. They made their way to Chicago, and Jan got a job in a corrugated paper company, where he remained for fifteen years. Amalie got a job in tailoring at Sears and Roebuck. They bought a home in Chicago, where they lived for fourteen years before selling it and moving to Cicero. They remained in Cicero for their last twenty years together.

In 1990, Amalie died of cancer. Jan has not yet recovered from this blow. After Amalie’s death, a Mrs. Martinek, a friend of Amalie’s for over thirty years, took Jan in to live with her. Jan became terribly depressed, however, and in 1993 tried to kill himself. Mrs. Martinek found him in time, however, and brought him to the hospital. From there he has been discharged to a nursing home for Czechs and Slovaks, where it is hoped he will make a smooth transition.

Though Jan is a talkative, pleasant, well-mannered, well-groomed, lovely gentleman, he seems inherently sad and harbors a lot of anger, which seems to currently be directed toward Mrs. Martinek, whom, he says, “tricked him” into coming to the nursing home. And though he does not say it, perhaps he is angry that she foiled his attempt at suicide. He needs little in the way of medical care, but his depression lingers. Even if he were to improve, he has no home to go to. He has yet to make any new relationships with his fellow residents and instead spends most of the day sitting near the nurses’ station, talking to the staff any chance that he gets about the long, amazing life he has led.

(Originally written: December 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Ultimate Romantic appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 13, 2020

“They Don’t Know How Much We Love Each Other.”

Anton Lungu was born near Brasov, Romania on July 22, 1936 to Ciprian and Ileana Lungu. Ciprian was a soldier, and Ileana cared for their four children. Anton only went to the equivalent of seventh grade before he quit to work at a construction job. He stayed in construction his whole life, except for the two years he spent in the Romanian army. He served his time and even became an officer after attending a special training school. Once released, he returned to construction work.

Anton Lungu was born near Brasov, Romania on July 22, 1936 to Ciprian and Ileana Lungu. Ciprian was a soldier, and Ileana cared for their four children. Anton only went to the equivalent of seventh grade before he quit to work at a construction job. He stayed in construction his whole life, except for the two years he spent in the Romanian army. He served his time and even became an officer after attending a special training school. Once released, he returned to construction work.

As a young man, Anton was apparently very handsome and popular. He had a motorcycle, a leather jacket and lots of girlfriends. He did not really fall in love, however, until he was 28 years old when he happened to meet the daughter of his boss. The girl’s name was Bianca Ardelean, and at the time that they met, she was only 17 years old. From the moment that he met her, Anton spent every day trying to persuade Bianca to go for a ride with him on his motorcycle, and each time she would refuse. One day, however, she finally said yes. Delighted, Anton devoted the whole day to her, spoiling her and giving her gifts and then, according to family legend, refused to bring her back home! At the end of the day, he proposed to her, and she said yes, so they drove off to elope.

Unfortunately, however, their plan was foiled. Since Bianca was still a minor, she was required to have her parents’ permission to marry, so they were turned away from the registrar’s office. In their own eyes, however, they were “married” and found a place in town to stay for the night. They then found an apartment, where they proceeded to live as man and wife. When Bianca’s father finally discovered his daughter’s whereabouts, he was furious, but Bianca refused to leave, saying that she was Aton’s “wife.” Anton continued to work construction, and Bianca cared for the two children that eventually came along: Bogdan and Crina. It was not until Crina was seven that Anton and Bianca finally legalized their marriage.

Crina reports that her father idolized her mother. He spoiled her constantly and often claimed that Bianca was “the greatest woman in the world,” and that no one else even came close. Crina says that her parents were completely devoted to each other and that they had a very happy marriage.

In the early days of their relationship, Anton developed a pattern of working very hard at a job, saving money, and then quitting so that he and Bianca could spend weeks at a time together—going to the movies, going on picnics and taking long walks. When their first child, Bogdan, was born, however, Anton became more responsible and stopped quitting jobs. He began working fourteen hours a day, rarely took a vacation, and did everything for Bianca and his two children. Crina says that her father was a very hard-working, passionate man who was full of energy and life. He loved gardening and painting, and he never failed to clean the house from “top to bottom” every Sunday. Though he was passionate, he was never angry, Crina reports. “He never raised his voice to us, never screamed, yelled, swore or spanked.” His philosophy, she says, was that a person could be talked to rationally and be won over through kindness.

In 1984, when Anton was 48 years old, he decided that the family should leave Romania and move to the United States. Bianca had a sister, Anca, who had been living in America for twenty years and who would periodically return to Romania to visit family and friends. The Lungu family loved hearing Aunt Anca’s stories about her life in America, and they would sit enraptured, listening to her tales. After one particularly nice visit from Anca, Anton decided that they, too, should move to America—that it would be good for the children to live there. Crina says that her father was always up for an adventure and that this seemed like “a wonderful one to undertake.”

Thus, in 1984, Anton moved the family from Bucharest to Chicago, which is where Anca was living. They all bought a house together, and Anton found work in construction, just as he had in Romania. For the most part, the family enjoyed their new country and remained very, very close.

In 1991, however, Anton began experiencing severely debilitating headaches. He finally went to the doctor, who diagnosed him as suffering from an aneurysm. Anton was rushed into surgery, but suffered a stroke immediately following it, which left him in a coma for eight months. During those long months, Bianca rarely left his side. Eventually, Anton awoke from his coma, but he could not speak. Then, after several weeks, he began speaking in perfect English, with no accent at all, and with perfect grammar and diction. It was extraordinary, and no one could explain it, even the doctors. This lasted only a brief time, however, before he lost this ability and oddly went back to speaking Romanian, apparently with no knowledge of his ability to speak perfect English.

Anton was eventually allowed to go back home, with the family taking turns caring for him around the clock. Unfortunately, the situation became worse when Bianca received news that her father back in Romania was dying and that he was asking for her to come back for one last visit. Bianca was very torn about what to do considering the sometimes rocky relationship she had with her father ever since she ran off to marry Anton. She desperately wanted to make her peace with him, but she felt she could not possibly leave Anton. Eventually, Bogdan and Crina made the decision for her and insisted that she go back to Romania, promising that they would care for Anton in her absence.

Bianca finally agreed to go, but almost immediately upon her departure, Anton began to go “down-hill.” He had already been suffering from confusion and obsessive thinking, but it got worse without Bianca constantly by his side. In her absence, he began to have increasing episodes of shouting and screaming, which was completely out of character for him, and he refused to let anyone help him, even Bogdan and Crina. In desperation, his children called his doctor, who then arranged for Anton to be temporarily placed in a nursing home until Bianca returns.

Anton has not made a very smooth transition to the facility and constantly asks for Bianca. Finally, Crina told him that Bianca is ill and in the hospital. They do not dare tell him that Bianca is in Romania, as they feel this would push him over the edge, as he constantly begs to be taken back there himself. Bogdan and Crina visit daily, counting down the days until their mother returns from Romania. Once she is back, they plan to take Anton home, where his dog, Charlie, is apparently pining away for him. The staff have cautioned them that removing Anton is very unrealistic because of the level of care that he requires, but, Crina says, “they don’t know how much we love each other.”

(Originally written: October 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “They Don’t Know How Much We Love Each Other.” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 6, 2020

“An Amazing Zest for Life!”

Wilma McDonald was born on April 10, 1910 in Chicago to Lech Kaszubski and Berta Kaluza. Not much is known about the origins of Lech and Berta. It is believed that they were both born in Chicago, though there parents had been born in Poland. They did not call themselves Poles, however, but Kashubs, which is apparently an ethnic Slavic group descended from medieval Pomeranians. Whatever their exact origin, Lech and Berta married young and attempted to make a life in Chicago. Lech started out building truck bodies back in the days when they were still crafted of wood. Later in life, he decided to open a restaurant near Milwaukee and Devon. The restaurant was located right between two cemeteries, so a big source of Lech’s business was funeral dinners. Berta, meanwhile, was a housewife who cared for their three children: Wilma, Cecelia, and Albert.

Wilma McDonald was born on April 10, 1910 in Chicago to Lech Kaszubski and Berta Kaluza. Not much is known about the origins of Lech and Berta. It is believed that they were both born in Chicago, though there parents had been born in Poland. They did not call themselves Poles, however, but Kashubs, which is apparently an ethnic Slavic group descended from medieval Pomeranians. Whatever their exact origin, Lech and Berta married young and attempted to make a life in Chicago. Lech started out building truck bodies back in the days when they were still crafted of wood. Later in life, he decided to open a restaurant near Milwaukee and Devon. The restaurant was located right between two cemeteries, so a big source of Lech’s business was funeral dinners. Berta, meanwhile, was a housewife who cared for their three children: Wilma, Cecelia, and Albert.

Wilma went to school until eighth grade and then worked at the family restaurant until she was sixteen. At that time, she asked her parents if she could quit and instead got a job at M. Snower as a seamstress doing what was called “piece work.” Lech was reluctant to give up one of hes best workers, but Berta convinced him to let Wilma try something else. At M. Snower, each girl had a minimum number of garments that she needed to produce in order to receive her base pay. Anything the girls produced beyond the minimum got them a bonus. Wilma really enjoyed this job, so much so that she stayed at the company for fifty-four years, retiring when she was seventy! Every day of her work week, she took two buses and the el to get there.

As a young woman, Wilma lived for dancing. She loved to hear the big bands at the Aragon, Trianon and the Rainbow. It was at one of these dance halls that she met Martin McDonald, whom she eventually married. Marty had a job unloading mail off of boxcars, and the couple lived on McLean Avenue. They had one child, Russell. When the war broke out, Marty joined the army and managed to make it back safe, only minimally wounded, after two years of active duty. He got his job back unloading the mail, but he and Wilma were not the same. They began fighting a lot and could no longer see eye-to-eye on anything. Finally, when Russell was eight, the couple divorced. Wilma lost contact with Marty and supported Russell alone on her wages as a seamstress.

Russell reports that his mother was always on the go. She had “tons of hobbies” and was always full of life. Besides music—big band in particular—Wilma also loved the movies and went religiously, every Sunday, to the cinema. She was also obsessed with crocheting afghans and knitting doilies and was constantly doing this in her spare time, even to age eighty-two. She was an avid reader, her favorite genres being mystery and romance, and she would check out at least six books at a time and return all of them, finished, after two weeks.

Perhaps the biggest love of her life, though, was her grandson, Joseph. In 1972, when Joseph was born, Wilma moved in with Russell and his wife, Eva, and helped to take care of Joey, even though she was still working herself. She was a huge part of Joey’s life and was always interested in what he and his friends were up to. Even as teenagers, if Joey had friends over for a BBQ, Wilma could always be found in the midst of them, having fun and joking with them. She genuinely loved all young people in general, and enjoyed spending time in their company.

Up until the age of sixty-five, Wilma had never traveled beyond the Chicago city limits. But upon her sixty-fifth birthday, she decided to take up traveling and went on bus trips all over the United States and even made it to Hawaii. Over the years, she has belonged to several parishes: St. Stanislaw, St. Sylvester, and St. Cornelius, but never joined any groups or ministries in any of them, even in recent years, because, she claimed that everyone in those groups was too old!

Wilma continued working until she was seventy, but even after she retired, she kept up her very active lifestyle—which included smoking and drinking—until she was around seventy-seven, which is when she experienced the first of her “spells.” She says she was at the library when the first one occurred. Russell came and got her and took her to the emergency room, where she had “every test known to man.” Nothing significant was found, but she continued to have several of these “spells” over the next six or seven years, each time experiencing a small loss in cognition as a result.

Recently, one of these spells caused her to fall, and she broke a hip. While in the hospital recovering, she fell and broke the other hip. Much to their great sorrow, Russell and Eva, who is experiencing her own serious health issues, felt they could not care for Wilma any more at home, especially considering her two broken hips.

Russell, who is not able to visit often because most of his time is taken up caring for Eva, describes Wilma as a very strong woman who never let things bother her. He thinks that one of the reasons she liked to keep so busy was so that she wouldn’t have to dwell on the past or current worries. “She has an amazing zest for life,” Russell reports. “Nothing ever slowed her down.” She prayed novenas often and surrounded herself with a lot of friends as a way of coping, he says. Her grandson, Joe, who was such a big part of her life, lives in Montana now and has not yet been to see her since her admission.

Overall, Wilma is a very alert, pleasant woman who enjoys all aspects of the nursing home. Only occasionally is she disoriented and confused, during which times she politely asks the staff to call Russell or Joey to come and get her. Her favorite activities are bingo, game night, and big band hour. She loves talking to the other residents and is very outgoing.

(Originally written: November 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “An Amazing Zest for Life!” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

January 23, 2020

“A Pillar of His Community”

Leonard “Leo” Frazier was born on October 7, 1906 on a farm in Minnesota to Lewis and Marion Frazier. Lewis was born in Minnesota, and Marion was a German immigrant. Together they had eight children, of whom Leonard was the youngest.

Leonard “Leo” Frazier was born on October 7, 1906 on a farm in Minnesota to Lewis and Marion Frazier. Lewis was born in Minnesota, and Marion was a German immigrant. Together they had eight children, of whom Leonard was the youngest.

When Leo was only three years old, his father died. His mother eventually remarried and had two more children. Leo’s stepfather was apparently very abusive to him and to his mother, and Leo only went to school until roughly the 3rd grade before he was made to work on the farm. As he grew older, he also worked as a hired hand on surrounding farms and even worked, as a young teen, on a ranch in Montana for a while with his brother, Arthur, who had found work there as a blacksmith.

When he was about seventeen or eighteen, Leo decided to make his way back home from Montana, but found work along the way in Chicago, working construction. He decided to stay and worked to get himself established before finally completing the trip back to Minnesota, determined to rescue his mother from his abusive stepfather. Marion apparently did not need much convincing, and she escaped with Leo. Together, they bought a small house in Oak Park, Il. though it was a struggle to keep it, especially once the Great Depression hit. Eventually, however, almost all of Leo’s brothers migrated down to find work in the city and lived in the house with Leo and Marion.

In the 1930’s, Leo and his brothers formed the Frazier Brothers Construction Company. Leo worked very hard, mostly doing remodeling work, and employed a man, Fred Schneider, to build cabinets in the garage behind their house in Oak Park, which Leo would then install in various homes. Eventually, Leo formed a separate company called Frazier Home Utilities Company, which basically consisted of his arrangement with Fred to build cabinets as well as a lumber supply company of sorts.

When the war broke out, however, Leo found himself too busy to install the cabinets Fred was building. Instead of remodeling and home construction, Leo and his brothers found themselves building barracks at Fort Knox and also did work for Chrysler at Great Lakes, which was producing products for the war effort.

After the war was over, business boomed for the Frazier Brothers Construction Company and Leo was swamped with work. He still managed, however, to build a handful of homes himself from the ground up, many of which can still be seen today in Villa Park.

When Leo was twenty-four, he was set up on a blind date with a young woman, Lucille Cotter, who was four years his junior. The two of them hit it off right away and got married in 1930. They had two children: Sidney and Sissie, and Lucille acted as the bookkeeper for both of Leo’s companies. After the Depression, Leo’s brothers eventually married as well, and one by one, left the house until only his mother, Marion, remained. She lived with Leo and Lucille until 1950, when she fell and broke her hip. Upon her release from the hospital, however, she needed so much care that Leo was forced to put her in a nursing home. She died soon after at age eighty-three.

Leo and Lucille apparently had a very happy marriage, one of their favorite hobbies being square dancing. They became friends with a couple who were famous in the region as “callers”—Lulubell and Scottie McPherson. The four of them remained friends for many years, and Leo even did work on their house in Oak Park for them.

Besides square dancing, Leo’s other passion in life was horseshoes. Apparently, Leo traveled all over the country—and the world!—competing in competitions and won over 100 trophies. Leo’s son, Sid, says that he rarely saw his father when he was growing up, as he was always working or away at a horseshoe competition. Leo was also an active member of the “Freedom Through Truth Foundation,” which was a civic group that focused on educating people about how money is created, circulated and used by the government or big businesses to keep people in debt.

In 1984, Leo felt it was time to retire and accordingly dissolved Frazier Home Utilities Company, but he allowed his nephews to take over the Frazier Brothers Construction Company. About four or five years later, however, it closed, too.

In 1993, Lucille passed away, which is when all of Leo’s troubles began, says Sid. Lucille’s death was terribly hard on Leo, as they had been married 63 years. He became depressed and angry and then began to slip mentally. Finally, it was decided that Sid would move in with his father for a time, hoping that if he could provide balanced meals for him, his confusion might get better. Even under Sid’s supervision, however, Leo got progressively worse, so Sid and his wife, Jean, finally arranged for Leo to be admitted to a nursing home. Leo’s daughter, Sissie, lives in Vermont and is not a part of his care plan, though she calls several times a week to talk to him.

Leo is able to communicate at times, but he remains very confused. He spends most of his time wandering the halls and periodically attempts to leave the facility. He is easily redirected, however, and does not become agitated. Frequently he asks for Lucille or Sid. Sid visits as often as he can and attempts to play checkers or chess with his father, which Leo used to love and which was one of the few things that he and Sid shared as Sid was growing up. At first, Leo seems enthused to play but then quickly becomes distracted.

Sid ruefully reflects that despite the fact that Leo wasn’t the most active, present father, he was was “a real pillar of his community. Everyone respected him.”

(Originally written: February 1995)

The post “A Pillar of His Community” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 19, 2019

She Lived to be 100!

Tereza Hlavacek was born on August 15, 1895 in what was then called Bohemia, the part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that later became Czechoslovakia. Her parents were Dobroslav and Marie Cipris, about which little is known. Tereza was one of four children and attended grammar school before she quit to start earning money, which the family desperately needed. She didn’t have much luck, however, so when she was just fifteen or sixteen, she decided to follow her older sister to America, hoping to get a job there. She made the journey alone and traveled to Chicago, where her sister was living in a boarding house. An uncle, Joseph Krall, also lived nearby, and he gave Tereza a job working in his tailor shop.

Tereza Hlavacek was born on August 15, 1895 in what was then called Bohemia, the part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that later became Czechoslovakia. Her parents were Dobroslav and Marie Cipris, about which little is known. Tereza was one of four children and attended grammar school before she quit to start earning money, which the family desperately needed. She didn’t have much luck, however, so when she was just fifteen or sixteen, she decided to follow her older sister to America, hoping to get a job there. She made the journey alone and traveled to Chicago, where her sister was living in a boarding house. An uncle, Joseph Krall, also lived nearby, and he gave Tereza a job working in his tailor shop.

Not long after she arrived, Tereza was introduced to Bernard Hlavacek, who did odd jobs for her uncle and also worked as a delivery man. Bernard, a quiet, shy boy, supposedly fell in love with Tereza right away, impressed by her ability to work hard and the way she always comported herself. He was nervous to ask her out, however, fearing what her uncle would say, and instead spent a year worshipping her from across the shop. Finally, Tereza’s uncle pulled him aside one night and asked what he was waiting for. Bernard, stunned with relief and overcome with joyful hope, asked Tereza the very next day to walk with him in Humboldt Park, to which she said yes. They began dating in earnest, then, and married shortly after.

Once married, Tereza stayed home to be a housewife, and Bernard continued working with her uncle, having been elevated now to a full tailor. Eventually the young couple was able to buy a small house with a big yard, which Tereza converted into a huge garden and which she diligently worked in every day. They had two sons, Joseph and Simon, both of whom Tereza was very attached to.

Tereza toiled endlessly for her little family and was reportedly a very strong, independent woman. She was apparently quite stubborn and wanted her own way in most things, but she was also most appreciative of any little thing anyone ever did for her or gave to her. Her daughters-in-law report that Tereza was also a little bit vain, her appearance always being very important to her. Though they had little money, Tereza made it a point to always be nicely dressed. There is a family story that once when one of Tereza’s friends was about to leave on a trip to Europe, Tereza was so disgusted by her friend’s old, tattered hat that she whipped off her own hat and gave it to her, saying “Here! Take mine!” Even in her nineties, Tereza always donned a sweater because she was unhappy with how her arms looked.

Though Tereza has always been a strong woman, she has also been a very nervous person, especially as the years have gone on. Apparently, when Joseph and Simon both went into the army, Tereza became so fraught with worry that her ears “started draining” and she went deaf in one ear. The worst blow to her nerves, however, was when Bernard passed away at age 57. He had a stroke while working in the yard and was taken to Cook County Hospital. Tereza visited him faithfully each day, but on the third day, when she arrived to see him, she was shocked to find his bed empty. When she asked where her husband was, she was told nonchalantly that he had died in the night. From that point on, Tereza says, she developed “the shakes.”

After Bernard’s death, Tereza threw herself into community and church activities. She still gardened and traveled daily from Cicero to the Bohemian National Cemetery in Chicago to lay flowers on Bernard’s grave, a ritual she kept up for six years. In addition, she began cooking for the Bohemian club she belonged to and also started crocheting again. She had always enjoyed crocheting as a hobby, but after Bernard’s death, it became almost a frenzied obsession. Her daughter-in-law, Rita, says that she must have produced thousands of baby booties over the years. She also found solace in traveling and went to Oregon, Florida, Hawaii, and to Europe twice. Sometimes she used a travel planner, but sometimes she made all her own arrangements.

Tereza continued to live independently until 1982, when she had to have a hip replacement. It was then that her son, Joseph, persuaded her to move in with him and Rita. This seemed appropriate to Tereza, Joseph being the oldest, though her favorite was Simon, whom she always referred to as “my baby.” Tereza’s hip mended well, though she continued to have pain on and off through the years. It didn’t stop her from being active, however, and she continued to garden until she was 94.

Unfortunately, Joseph passed away from cancer in 1985, just three years after Tereza had moved in. It was a terrible blow, again, for Tereza and for Rita, but they helped each other get through it. After her son’s death, Tereza began to slow down and became much weaker than she had been. She had to rely on Rita for things she had always been able to do herself, such as bathing and dressing. Simon and his wife, Norma, not wanting all the burden of care to be on Rita, started coming over regularly to help, but it was difficult for them all. Rita developed severe arthritis and became increasingly worried that something would happen to Tereza, such as a fall, and that she wouldn’t be able to help her. Finally the stress grew so great that the four of them sat down and discussed the possibility of Tereza going into a nursing home. Tereza was not thrilled by the suggestion, but she was not unreasonable and seemed to understand that she did not have a lot of choices. They all went and toured several places, and Tereza eventually chose The Bohemian Home for the Aged on Foster and Pulaski because it was so close to the Bohemian National cemetery, where Bernard was buried, and because there were so many residents with whom she could speak Czech.

Tereza moved into the nursing home in 1993, at age 98. Her transition was relatively smooth, though she at first spent all of her time in her room, furiously crocheting. When the staff attempted to intervene and suggest that she limit the amount of time she spent crocheting so that she could meet other residents and participate in the facility’s activities, she grew angry and refused to crochet any more. She wanted complete control of her hobby, she said, or she didn’t want to do it all. She called Simon to come pick up all of her crochet materials and hasn’t engaged in this activity since, though many residents and staff have tried to persuade her otherwise.

Tereza did eventually begin to come out of her room and meet people, but her favorite activity was visiting with Simon, who came to visit her two or three times each week for over a year. Tereza and Simon seemed to have a very special relationship, and he was able to calm her in any situation. He often took her walking in the facility’s gardens and would sit outdoors with her, just talking or laughing. He was always able to understand her and was likewise always able to get her to understand him, despite her hearing loss. According to Simon’s wife, Norma, the two of them had a strange connection in that he would always appear at the nursing home just when Tereza seemed to need him most.

Sadly for all, Simon passed away in 1994 of bone cancer. His dying request to Norma was to never tell Tereza that he had died—to keep his death from her. Norma and all the rest of the family agreed, though it has been very painful for them to keep up the pretense, even now. Norma and Rita still visit her, but not as much as Simon used to. When Tereza inevitably asks why Simon didn’t come, Norma lies and says he is at home in bed with a bad back. Tereza seems to accept this story, but she is always sad and worried about him, especially when he wasn’t there for her 100th birthday party. On that occasion, Norma told her that Simon had to stay home with the flu. It is a situation that neither Norma or Rita are comfortable with, but they don’t know what else to do.

Besides her worry about Simon, Tereza is seems happy. She is remarkably cognizant and able to get around on her own throughout the home. She enjoys sitting and talking with other residents the most or watching Lawrence Welk on TV.

(Originally written: September 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Lived to be 100! appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 5, 2019

“It’s Not The Real Albert”

Albert Daelman was born on September 5, 1916 on a farm in LaSalle, Illinois to Ernst and Willemina Daelman, Dutch immigrants. Ernst was a farmer and was what Albert describes as “a hard-working man.” His mother, Willemina, cared for their six children. Albert managed to attend high school for a year and a half before he quit to get a job. When the WWII broke out, he enlisted in the army and was stationed in the Philippines.

Albert Daelman was born on September 5, 1916 on a farm in LaSalle, Illinois to Ernst and Willemina Daelman, Dutch immigrants. Ernst was a farmer and was what Albert describes as “a hard-working man.” His mother, Willemina, cared for their six children. Albert managed to attend high school for a year and a half before he quit to get a job. When the WWII broke out, he enlisted in the army and was stationed in the Philippines.

Upon being discharged and returning home, Albert decided to move to Chicago and found work as a machinist in various factories. At one point, he decided to take a vacation to San Francisco and happened to meet a beautiful young Mexican woman, Benita Caldera, who was also vacationing there. Albert took her out to dinner and afterwards asked her if he could write to her. Benita agreed to give him her address, though she had a boyfriend back in Mexico. She lived in a small town there and worked as a manager of a furniture store. She and her sister lived together with their invalid mother, whom they both took care of.

True to his word, Albert wrote to Benita as soon as he got back to Chicago and continued to write to her every week. The problem, however, was that his letters were mostly in English with a few Spanish words thrown in for good measure. Benita was unable to read them, so she had to have a friend or sometimes the parish priest interpret them for her. Pretty soon the whole village knew of Benita’s American “lover,” which prompted Benita to begin taking English lessons.

Things continued this way until Benita’s mother suddenly died, and Albert went to Mexico to attend the funeral. He stayed for two weeks, at Benita’s sister’s insistence, so that he could get a good picture, she said, of who they were and how they lived. It didn’t take long for Albert to propose to Benita, and she accepted him. At first they planned to get married in her local church, but Albert refused to pay the steep fee the parish priest was requiring, so they went to Chicago and got married at St. Viator’s.

Benita tried hard to adjust to her new life in America, but it was difficult at first. She says that a German couple who lived next to them were very kind to her, but even so, each evening she would sneak out onto the porch and cry with homesickness. Eventually Benita got used to being Albert’s wife, however, and things settled down. She managed to get a job working in accounting at the Lions International Headquarters, and Albert continued working as a machinist, his longest employment being with Victor Products. They never had any children, though Benita says she would have liked to.

Benita vehemently states that Albert was “a good, good man—an honest man,” but, she adds, “he was not very friendly.” Albert, she says, had “a complex” about being around people. He was very shy and nervous and angered easily. Benita says that he had no hobbies and no friends and dealt with stress by drinking a lot and complaining about every little thing.

His routine was to go out to the local tavern on Friday nights after work, where he proceeded to drink away the majority of his paycheck. When he came home drunk, Benita would put him to bed and then go through his pockets to see if there was any money left. This went on until he retired, and Benita finally persuaded Albert’s doctor to tell him that if he didn’t stop drinking he would die. Apparently, this convinced Albert, and he stopped drinking cold turkey. Albert went on to get a job as a security guard at Colonial Bank on Belmont, where he worked for five years until he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

Despite having treatments, Albert’s lung cancer has spread to his brain, which seems to have further effected his personality and has caused him to be disoriented and confused. Benita tried to care for him at home for several years, but when Albert became at times verbally and possibly physically abusive to her, she could no longer cope. Not knowing what else to do, Benita recently placed him in a nursing home, which he is not adjusting well to. He continually blames Benita for bringing him here and becomes agitated whenever she visits. Indeed, on one occasion, he attempted to strangle her. His two obsessions seem to be sneaking off to bed or repeatedly saying “get me out of here.”

All of this is particularly hard on Benita, who claims that she loves him still, despite his verbal abuse. “It is not the real Albert,” she says, and is overwhelmed with grief and guilt that she cannot help him more.

(Originally written: March 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “It’s Not The Real Albert” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 28, 2019

“Jesus Has Always Been With Me”

Celina Abelli was born on August 18, 1898 in a small Polish village to Wera Pakulski and Olek Zuraw. Celina says the family lived on a farm with beautiful fruit trees. Besides farming, Olek worked as a carpenter and even built the house they lived in. In addition, he cut and sold logs from a nearby forest and helped cut hay on local farms for extra money. Wera, meanwhile, cared for their six children: Zygfryd, Waldemar, Kaja, Helena, Teodor and Celina. Wera had a total of nine children, but three died of typhus fever before Celina was born: Konrad, who was seven when he died, and Lew and Marek, who were twin baby boys.

Celina Abelli was born on August 18, 1898 in a small Polish village to Wera Pakulski and Olek Zuraw. Celina says the family lived on a farm with beautiful fruit trees. Besides farming, Olek worked as a carpenter and even built the house they lived in. In addition, he cut and sold logs from a nearby forest and helped cut hay on local farms for extra money. Wera, meanwhile, cared for their six children: Zygfryd, Waldemar, Kaja, Helena, Teodor and Celina. Wera had a total of nine children, but three died of typhus fever before Celina was born: Konrad, who was seven when he died, and Lew and Marek, who were twin baby boys.

When Celina was just four and a half, Olek died at age forty-four of pneumonia. Celina has just one memory of him, which was of him lifting her up into the fruit trees to pick a piece of fruit for herself. After Olek’s death, all of the children had to find work, except Teodor and Celina who were too young. Both of them continued at school for a few years and then also quit. Celina found work sewing or doing “any little thing that came along.”

The siblings all worked hard, and occassionally Wera allowed them to go into town to attend dances in the evenings. It was at one such dance that Celina’s sister, Kaja, met a young man by the name of Emil Brzezicki. Unfortunately, however, Emil only had eyes for Celina, who for some reason instantly hated him. Emil wouldn’t give up, however, and began following Celina everywhere she went, even bringing her flowers on many occasions, much to Celina’s embarrassment and Kaja’s despair. Celina won’t say exactly why she didn’t initially like Emil, nor has she ever said why she eventually agreed to marry him. No one in the family can shed any light on why Celina changed her mind, though her daughters suspect that something dark may have happened. When asked if she grew to love Emil, Celina says, “I didn’t hate him, but I didn’t love him, either. It was something in between. We got by.”

After they were married, Celina and Emil lived with Wera before eventually moving to a neighboring town a year later. Together, they had eight children, but two died when they were small. Celina doesn’t have much to say about their life in Poland during the 1930s and ’40s, or how they survived the war, just that after it was over, the whole family moved to America around 1950. One of their sons, Simon, was delayed in Poland for a time, but he eventually joined the family in Chicago, which is where they had made their way to. He left again almost immediately, however, to join the American army.

In Chicago, Emil found work in a furniture factory, but he had to quit after only four years because he was diagnosed with emphysema. Realizing that Emil’s prognosis was not good, Celina knew she had to find some sort of employment and managed to buy a little corner grocery shop. She ran the store and nursed Emil, who eventually died seven years later in 1961. Celina kept the store running even after Emil died, but she says it was hard because it was the era when big chain grocery stores were buying up all the little neighborhood shops. After two years, she gave in as well and sold it. After that, she found work as a nurse’s aide.

In 1970, Celina married again—this time to a quiet, mild-mannered Italian man, Stefano Abelli, who was eight years her senior. She says she loved Stefano, but when asked about their relationship, she says, “Well, it wasn’t sweet 16!” Celina and Stefano’s relationship was short-lived, however, as Stefano died of cancer after only a year and a half of marriage. Following his death, Celina lived alone for many years. Two of her daughters died—one of a heart attack at age fifty-five and one of cancer in her forties. Her other four children are scattered in other parts of the country, so that as her health has begun to decline, Celina has been relying more and more on her grandchildren who still live in the area.

In just the last couple of years, Celina has had a stroke and fractured her spine, among other things, which has caused her to have to live with various grandchildren. When she needed an operation on her leg, however, she was hospitalized and from there sent to a nursing home to recuperate. She wishes she could go home to one of her grandchildren’s houses, but she realizes this is unrealistic. She is not making a smooth adjustment, however, and says she is in a lot of pain, calling out frequently because of it. However, if anyone sits and talks with her at length, even for an hour or longer, she never once complains of pain or cries out.

Celina says that she has no hobbies because she never had time for fun; she was always working. Occasionally she would go to a movie or listen to music, but her biggest interest was probably the church. She says that she can recite the whole mass in Polish without one mistake. Celina relates that she has always prayed from the time she was a little child and has gotten a lot of strength from prayer over the years. She says that “Jesus has always been with me,” and that “I’m very religious. Very deep. But I lost a lot of faith when I came here because it’s hard to stay religious in a country like this.” Indeed, she says that when she remembers how life used to be in Poland “I am bitter” and “I want to die.” She cries easily and seems particularly fixated on the 1986 space shuttle explosion.

Attempts have been made to involve her children in her care, but they are all older themselves and have their own health problems. One son recently sent her twenty dollars in a card, which Celina was thrilled with and proudly showed to all of the staff. Overall, however, Celina remains depressed and despondent, reluctant to start life over yet again.

(Originally written: April 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Jesus Has Always Been With Me” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 21, 2019

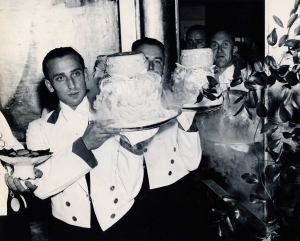

From Professional Waiter at the Drake Hotel to Navy Bartender

Gonzolo Rochez was born in Texas on February 2, 1908 to Fernando and Sonia Rochez “a few years” after the U.S. “took over” Texas from Mexico. This event, however, occurred in 1848, so he is off by a few years, though maybe he views it from a different perspective. Gonzolo enjoys telling his life story to anyone who will listen, though he frequently repeats “I had a horrible life.”

Gonzolo Rochez was born in Texas on February 2, 1908 to Fernando and Sonia Rochez “a few years” after the U.S. “took over” Texas from Mexico. This event, however, occurred in 1848, so he is off by a few years, though maybe he views it from a different perspective. Gonzolo enjoys telling his life story to anyone who will listen, though he frequently repeats “I had a horrible life.”

According to Gonzolo, his parents died when he was five or six years old. He says that he doesn’t remember them at all and doesn’t know how they died. He was sent to live with his godmother in the same village, but she was old and poor and couldn’t really take care for him. Not knowing what else to do, she sent him to an orphanage run by nuns. Gonzolo hated life at the orphanage. He says that he was taught to read and write, but that he was always hungry, so he decided to run away. He became a street urchin, then, wandering from place to place and was constantly “bumped or kicked around.”

In his late teens or early twenties, Gonzolo made his way to Chicago with a few friends, where he found a job in a restaurant. Eventually, he found a place to live as well and sent for his girlfriend, Angelina Poblete, back in Texas to join him. Gonzolo and Angelina soon married, and Gonzolo began to look for a better job. Gonzolo eventually landed a position at the Drake Hotel—“the best of the best,” where he earnestly began to “learn the trade” of being a professional waiter. For forty years, he worked as a waiter at only the best hotels: the Drake, The Blackstone, The Congress, and the Ritz-Carlton. Gonzolo says of this time period: “I was healthy, I didn’t complain, and I made a living.”

It was also during this time that he took up the hobby of painting. He says that one weekend he happened to be walking around State Street and saw a painter painting the crowd. Looking over the painter’s shoulder, he decided it didn’t look that hard, so he went to a dime store and bought some paint and brushes. He was impressed with what he produced and took up painting in earnest. It became his life-long hobby. Apparently, a wealthy business man who once saw Gonzolo’s paintings offered to pay for him to take art classes, but Gonzolo refused his offer, saying “I want to paint what I want to paint, not what they tell me.” Gonzolo claims that both the Drake and the Congress Hotels possess some of his artwork.

When WWII broke out, Gonzolo joined the navy and was stationed for four years in Ottumwa, Iowa, where he quickly became the company bartender. He was apparently liked by everyone, especially the officers, and was “treated very well.” He and three other men became “untouchable” because they were well-liked by the officers and were therefore given special favors. Once, he says, he confided to an officer that he didn’t feel like he was doing much to help the war effort and worried what he would tell people back home. The officer assured him that he was “helping as much or more with morale.” Gonzolo says that those four years in the navy were the best of his life. He would have stayed in if he didn’t have Angelina and two children, David and Eva, waiting back at home for him. Only occasionally did he go back home to visit them, and when his four years of service were up, he reluctantly returned to Chicago and continued on with his career as a waiter.

Being away for four years, apparently did not improve what was already a rocky marriage between him and Angelina. Gonzolo’s daughter, Eva, reports that he was a terrible husband and father. She says that Gonzolo was a very controlling, domineering, manipulative man who beat Angelina and David, but never her. The story of refusing art classes, she says, proves how much control he needed, that he would never subject himself to any outside authority. “No one could tell him what to do,” Eva says. This is why, she says, he could never belong to a church. He was baptized Catholic, but doesn’t believe in God now. Gonzolo says that “religion is an invisible weapon of the government to control the masses.” Instead, he believes in “the supernatural power of the universe” and that “when you die, you go to the same place you go to when you sleep.” Eva says that he has always been hot-tempered and did not have many friends. Indeed, when asked about any significant friendships he has had in the past, he says “friends are make believe.” When asked how he has coped with problems over the years, he says simply “I never had any problems.”

Angelina died in the late 1980’s, so Eva has been caring for Gonzolo on and off over the last several years. David has been estranged from his father for the past twenty years and lives somewhere in California. When Gonzolo’s health began to fail recently, Eva took him in to her own home for a time, but quickly realized she could not endure his domineering, manipulative ways and brought him to a nursing home.

Gonzolo has not made the transition well and remains very depressed. “Why should I get better?” he asks. “So I can plunge down again? I’m old. I’m 88 years old. Let me die.” He has not participated in many activities, nor does he seem interested in forming any relationships with the other residents. His favorite thing is to do is to talk about the past with the staff. He admits to liking to learn new things, however, which he says he has always tried to do throughout his life. “It’s not hard to learn if you’re willing,” he says.

(Originally written: April 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post From Professional Waiter at the Drake Hotel to Navy Bartender appeared first on Michelle Cox.