Michelle Cox's Blog, page 19

January 13, 2021

The Odd Life of Joseph Hertz

Joseph Hertz was born on May 3, 1916 in Washington, D.C. to Victor Hertz and Lena Aerni. Victor was of German descent and worked as the head accountant in a large firm in Washington. Lena was of Swiss descent and cared for their two children, Joseph and Louisa, who were five years apart.

Joseph Hertz was born on May 3, 1916 in Washington, D.C. to Victor Hertz and Lena Aerni. Victor was of German descent and worked as the head accountant in a large firm in Washington. Lena was of Swiss descent and cared for their two children, Joseph and Louisa, who were five years apart.

When Joseph was very small, Victor was transferred to Columbus, Ohio. Joseph says he has only one memory from their time in Columbus. He remembers going to a park with his father and seeing some swans swimming on a small pond there. Joseph desperately wanted to pet them, so he wandered into the pond, not knowing how to swim. Miraculously, his father saw him just as he was going under and jumped into the pond to save him.

After only a few years in Ohio, Victor was again transferred, this time to La Grange, Illinois, where Joseph attended grade and high school. His father went golfing every Saturday at the country club, and when he was old enough, Joseph was allowed to go with him. Joseph was a hard worker and besides keeping his grades up, had various odd jobs, such as mowing lawns and weeding gardens. He eventually got a “real job” delivering groceries. Most of his time, however, was taken up in helping his “no good sister, Louisa.”

Louisa, five years Joseph’s senior, had married young and had a baby almost immediately. Louisa, it seems, was not the maternal type, and frequently insisted on Joseph coming over and watching the baby, Carolyn—or Carrie, as she was called—while she and her husband went out. Joseph said he loved Carrie and didn’t mind caring for her, but it was hard for him to balance everything. His dream was to go to Notre Dame and play football.

Just a few weeks shy of his high school graduation, however, a terrible accident occurred. There had been a school dance, which Joseph had attended. He had been set up with a date, and when the dance ended, he walked the girl safely home. As he was walking toward his own home, however, a car came around a curve and hit Joseph nearly head on. Joseph spent weeks in the hospital with a brain injury, and it wasn’t clear whether he would live or not. He finally came out of it, however, and began to mend, but his dreams of graduating from high school and going on to college were crushed.

His parents helped him at first, but eventually he was forced to move out on his own, though it is not clear why. With the help of his father, he was able to get a job in a laundromat, but when he didn’t show up for work one day and didn’t call, he was fired. He tried to explain to the manager that he had passed out and couldn’t call, but the manager didn’t believe him. He tried a variety of other jobs, but the same thing always happened. He would either pass out at home or on the job and would then be fired.

At one point he managed to get a job at Wallis Press, first on the cutting machine and then on the folding machine. He was very nervous that he might pass out while operating such heavy machinery, but he tried his best. Eventually, he did pass out and the owner insisted he go to a doctor. His foreman had taken a liking to Joseph and in the past had always covered for him, sometimes even punching him on and off the clock when he was really at home sick. Finally, though, when he passed out on the job and it was brought to the owner’s attention, he was forced to see a doctor. Not surprisingly, the doctor diagnosed him as “unfit to work” and said he would inform the foreman and the owner of the press that Joseph would not be coming back. Depressed, Joseph agreed and did not go back to say goodbye.

Several years later, while walking down a street in Chicago, Joseph felt a shove from behind and turned to see his old foreman from the press, who was clearly upset with him. He accused Joseph of walking off the job after he had done so much for him. Joseph hurriedly explained that the doctor he had been forced to go to had diagnosed him as “unfit to work” and that he was supposed to have sent some kind of a report to the factory verifying that. The foreman claimed that they had never received a phone call or a letter from this doctor, which had led them all, at the time, to believe that Joseph had merely quit. Joseph apologized for the misunderstanding, and the foreman felt so bad for him that he offered him a “light duty” job in the mail room if he wanted to come back. Joseph thanked him for the offer, but ultimately turned him down.

As it was, Joseph was at an all-time low. He claims that in his twenties and thirties, he was married two times, but that both wives had died. His first wife, Agatha, was a nurse he met while in the hospital after being hit by a car. He says that she died, however, soon after their marriage, and that he eventually met another nurse, Marion, whom he also married. Marion also apparently died, leaving Joseph alone in the world. His parents died young, and Louisa and family had since moved to Kansas and did not maintain contact with him.

Without a job or any hopes of ever being able to hold one down, Joseph became homeless and eventually began sleeping on park benches. One night, after some cops came by and tried to get him to move on, a strange man approached him and asked him if he needed a place to stay. Joseph said yes, but told the man that he had no money. The man asked him if he could stand living in the park for just one more night until he could get a place ready for him. Joseph said yes and the next day showed up at the man’s apartment, as instructed. Joseph says that there were many homosexual men living in the building, so he decided to stay with them for only a couple of nights. Whether through their help or on his own, he was eventually able to get a job at a restaurant and then at a newsstand.

Joseph seemed to be able to handle working at the newsstand pretty well. One customer became a sort of friend and eventually told Joseph that he knew a woman he would like to introduce him to if he was agreeable. Joseph said yes and, with his friend, went to meet the woman, Betty Lindh, who was living with her aunt, Thelma Kloburcher. Betty had been married before, Joseph learned, but her husband had routinely beat her, so she eventually divorced him. She worked at the Harvard Insurance Company, but, like Joseph, had been in a car accident, which left her “a cripple,” and she used a walker to get around.

Joseph and Betty took an instant liking to each other and married quickly, each one willing to overlook the other’s disability. Joseph accordingly moved in with Betty and Thelma, but it soon became evident that this arrangement wasn’t going to work out. Thelma became extremely jealous of any attention the Joseph and Betty gave each other, culminating in Thelma one day breaking a plate over Betty’s head.

After that, Joseph and Betty took a room at a boarding house at Clybourn and Fullerton for $16 a week, and later moved across the street to a one-bedroom apartment for $18 a week. According to Joseph, he and Betty had a very tumultuous sort of relationship. Joseph says that they loved each other very much, but that they had a lot of problems, the biggest one being Betty’s alcoholism. Joseph claims that she often did strange, unpredictable things, like waiting for him with a knife one night when he came home from work. She was furious with him for something, and Joseph thought she was waving the knife at him to make a point of scaring him. He was stunned, then, when she actually lunged for him and stabbed him in the side. He did not go to the hospital, however, not wanting to report it. Instead he bandaged it himself and waited for it to heal. He admits, though, that he was equally violent at times, and claims to have attempted to strangle her one night. Having violent, emotional battles, often involving some sort of physical abuse, followed by a speedy, dramatic make-up, seemed to be a recurring pattern in their relationship.

In 1987, Betty’s health began to go downhill, so much so that it became apparent that she needed to be admitted to a nursing home, as Joseph could no longer take care of her. Joseph couldn’t stand the idea of being parted from her, however, so he checked himself into the same nursing home. After only six months, however, Betty passed away, leaving a grieving Joseph behind. After her death, Joseph began to hate the facility and wanted to transfer to a different home. He appealed to the public guardian’s office, saying that he was a victim of elder abuse. A guardian was appointed, and though no proof of abuse was ever produced, the guardian was able to find a new placement for Joseph.

Joseph is currently enjoying his new surroundings, though he says he misses Betty terribly. He also misses some of the staff at the other nursing home whom he had gotten used to and who had befriended him. Still, he says, “you have to make the best of it.” His favorite thing to do is to watch baseball on T.V. and particularly enjoys it if a group of other residents sit near him.

(Originally written February 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post The Odd Life of Joseph Hertz appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

January 7, 2021

He Made the Beautiful Wood Interiors of Luxury Train Cars

David Doubek was born on January 24, 1906 in Czechoslovakia to Dusan Doubek and Bessie Fiala. David does not remember what type of work his father did, just that he died when David was nine years old. Left alone with three children, Bessie tried for a few years to make it on her own before she eventually decided to immigrate to America. Her brother, Paul, was living in Chicago and had written her many letters, urging her to come. Bessie finally worked up the courage to make the journey, taking David, who was then fourteen, and her youngest daughter, Simona, with her. Her oldest daughter, Renata, reluctantly stayed behind, as she was already married, and her husband’s health was too poor for them to make the journey.

David Doubek was born on January 24, 1906 in Czechoslovakia to Dusan Doubek and Bessie Fiala. David does not remember what type of work his father did, just that he died when David was nine years old. Left alone with three children, Bessie tried for a few years to make it on her own before she eventually decided to immigrate to America. Her brother, Paul, was living in Chicago and had written her many letters, urging her to come. Bessie finally worked up the courage to make the journey, taking David, who was then fourteen, and her youngest daughter, Simona, with her. Her oldest daughter, Renata, reluctantly stayed behind, as she was already married, and her husband’s health was too poor for them to make the journey.

While still in Czechoslovakia, David had learned carpentry and cabinet making, as well as how to play the violin. When the family arrived in Chicago, he went to night school to lerarn English and then rather quickly got a job for Northwestern Railroad making all of the wood furnishings for their train cars. He began as an apprentice and eventualy worked his way up to become a foreman.

When David was twenty-three years old, he married Marie Horak, who was just eighteen. Marie was one of David’s first friends in America. When they met, she was nine and he was fourteen. Though their families lived on opposite sides of the city, they both went to the same Czech church, and David remembers teasing her by pulling her braids any chance he got.

By the time Marie was sixteen, however, they had progressed to going on dates, though they were infrequent, not only because they lived so far apart, but because neither of them had very much money to spare. Likewise, they both worked a lot. Besides taking care of her five younger brothers and sisters and her mother, who was ill much of the time, Marie sometimes worked, on and off, as a secretary or as a waitress. Usually, then, their dates consisted of simply walking in a park together or going to a free flower show or perhaps Riverside Amusement Park whenever they got the chance. Still, they managed to fall in love.

Unfortunately, the year David and Marie got married, 1929, the stock market crashed. David lost his job at the railroad, and Marie lost her job, as well, which, at the time, was in a factory. “It was a real shame,” says Marie, that David lost his job because he was a truly gifted carpenter. Sometimes on a Sunday, he would take her to the rail yard where he worked to show her some of the first-class cars he had worked on. “They were beautiful!” Marie says. “Like works of art.” But with the country plunged into the Depression, there was not as much of a need for wood-trimmed, luxury train cars. Thus, he and many other skilled carpenters were let go.

David and Marie lived with Marie’s family for about ten years until they could get back on their feet. David eventually got a job as the foreman of a maintenance crew at Butter Brothers, downtown on Canal Street, and Marie found another secretarial job. Eventually, they were able to move into their own apartment, just down the street from Marie’s mother, where they remained for the rest of their married life. In fact, Marie, now age 81, lives there still.

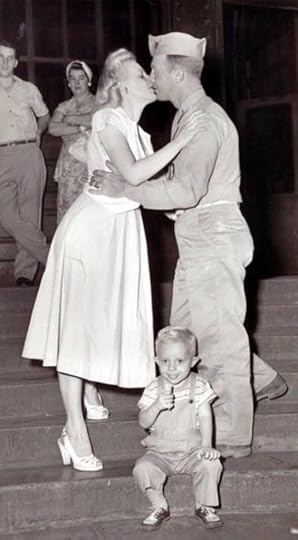

Not long after they moved to their new apartment, Marie got pregnant with their first child, David, Jr. They had begun to think they weren’t able to have children, so they were overjoyed when David came along. Marie quit work to stay home with him. When the WWII broke out, however, David joined the army—against Marie’s wishes—and was eventually shipped off to Europe. Marie had no choice but to take a job in an airplane factory as a drill press operator, leaving David, Jr and the new baby, Barbara, with her younger sister to watch. When the war ended, however, and David came home, Marie went back to being a housewife, and David was able to get his job back at Butter Brothers.

Marie says that they settled back into a routine and mostly stayed at home. Once David, Jr. and Barbara left home and got married, they joined a card club. They dreamed of going on a tour of Europe and perhaps on a cruise when they retired, but then, tragically, David had an accident when he was sixty, which altogether changed their plans.

It was 1966, and David was up on the roof, fixing a loose shingle, when he slipped and fell off. He shattered his leg, ankle and wrist and spent three and a half months in the hospital. He had a steel bar put in his leg, some bones in his wrist removed, and his ankle screwed together and was in successive casts for over a year and a half. He was forced, then, to go on full disability, and Marie had to go back to work. She was grateful that she was able to get some secretarial work, as she felt too old to work in a factory again. Laid up now, David turned to woodworking as a hobby to keep himself occupied and ended up making beautiful communion rails and pulpits for churches.

Eventually, Marie retired for good, but it was too difficult then for David to travel. To make matters worse, in 1992, when he was eighty-six, David had a stroke. He spent some time in the hospital and then one month further recovering in a Czech nursing home. Oddly, it was the same nursing home where his mother, Bessie, had been admitted to at age eighty-six. Both David and Marie were thus already very familiar with the home, Marie actually having spent additional time there as a volunteer, even after Bessie, her mother-in-law, had passed away. Still, however, Marie was determined to care for David at home, so she arranged for him to be released after only being there for a month. Mostly due to her, she says, David made almost a full recovery.

Two years later, however, David had another stroke, this one much worse, which left him unable to walk and unresponsive most of the time. He was again admitted to the nursing home, but his condition is now very serious. Marie, however, seems in denial of this and is still insisting that she will eventually take him home again like she did the last time. She spends most of the day at the nursing home, sitting by his bedside, and just recently celebrated Christmas here with him. The staff are attempting to help her process the true state of David’s health and likely prognosis. She remains dedicated, though, and says she is “optimistic” that David will come home again.

(Originally written: December 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post He Made the Beautiful Wood Interiors of Luxury Train Cars appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

December 31, 2020

She Met Her Husband at the Candy Shop

Wilma Ostrowski was born on January 7, 1909 to Adolf Achterberg and Lousia Keller in Stoddard, Wisconsin. Adolf and Louisa were of German descent, but were both born in Wisconsin—Adolf in La Crosse and Louisa in Manston. Adolf worked as a carpenter and was also the mayor of Stoddard for twenty-five years. Louisa cared for their ten children, all of whom lived into adulthood except one, Melvin, who died of a “throat epidemic.”

Wilma Ostrowski was born on January 7, 1909 to Adolf Achterberg and Lousia Keller in Stoddard, Wisconsin. Adolf and Louisa were of German descent, but were both born in Wisconsin—Adolf in La Crosse and Louisa in Manston. Adolf worked as a carpenter and was also the mayor of Stoddard for twenty-five years. Louisa cared for their ten children, all of whom lived into adulthood except one, Melvin, who died of a “throat epidemic.”

Wilma, who was one of the youngest in the family, only attended two years of high school. She would have liked to have gone on, she says, but in those days, the Stoddard Public High School only offered two years. In order to get her diploma, then, she would have had to travel to a neighboring town each day to attend a different high school. This was completely unrealistic for the Achterberg family, so she decided to quit and managed to get a part-time job doing laundry in a linen supply company.

Not long after Wilma started working, she met a young man, Simon Ostrowski, at a candy shop where she and some of her friends liked to go after work. Simon was seven years older than her and had come into the shop to buy some sweets for his mother’s birthday. Recognizing one of the girls gathered there, he went over to say hello and was then introduced to Wilma. After that, Simon began showing up randomly at the candy shop in hopes, he later told Wilma, of seeing her again. Whenever he did run into her, he always bought her a piece of candy and finally one day worked up the courage to ask her out on a date. Happily, Wilma accepted. Not long after, they began seriously “courting,” and two years later, when Wilma turned eighteen, they got married.

Simon was a carpenter like Wilma’s father, but once the depression hit, it was hard to find work. The young couple lived with Simon’s mother for a while but then moved to Lake Ross, Wisconsin; then to McGregor, Iowa; then to Genoa, Wisconsin; and then back to Stoddard, looking for steady work. Simon was able to find short-term jobs in each town, but never a full-time position that would allow them to stay. So after each job ended, the little family had to move again.

Finally, in 1941, Wilma and Simon decided to try their luck in Chicago and moved to an apartment on Elston Avenue. Simon was able to find a permanent job making cabinets, and Wilma cared for their three children: Donald, Mildred and Harry. After they moved to Chicago, however, they had three more: Albert, Lorraine and Thelma.

Wilma says she enjoyed being a mother and keeping house, especially after they finally settled down in Chicago. She loved baking, sewing and gardening and was a very active member of the Immaculate Heart of Mary Sodality. She was a quiet woman, her children report, but she loved being around people.

For reasons not explained, Wilma and Simon divorced in 1969 after 42 years of marriage. Wilma moved to her own apartment on Belle Plaine with their son, Harry, the only child still living at home. Harry had enlisted in the army and fought in the Vietnam War. While there, he was a victim of Agent Orange, among other things. When he was discharged home, he had many health problems, including diabetes. After several years of battling his illnesses, he had to have one of his legs amputated. He eventually died of a heart attack in August of 1994. Simon, meanwhile, had died in 1973 of a stroke and lung cancer.

Wilma was quite depressed over Harry’s death, but now says that she is “glad that he is no longer suffering.” She eventually returned to all of her old activities to try to help take her mind off of Harry’s death and likewise joined even more ministries at her church. She also spent a lot of time with her other children and their families, most of whom still live in the Chicagoland area. “I’ve always liked to keep busy,” she says. Not too long after Harry’s death, however, Wilma started having her own health issues and thus decided to preemptively move into an assisted-living apartment. Wilma has tried valiantly in the last few years to hold on to her independence, but she has fallen multiple times and has grown increasingly reliant on getting around in a wheelchair, so much so that her doctor recommended nursing home care.

Wilma says that she has always faced problems head-on, so, knowing that a nursing home was inevitably in her future, she decided to get it over with. “Why put it off until tomorrow?” she repeatedly asked her children. Each of her daughters offered their homes to her, but Wilma did not want to burden them. Instead, she reached out to Lorraine and Thelma and asked them to help her find a nursing home. Lorraine and Thelma are saddened, they say, about having to admit their mother, but they are relieved that she will be cared for and stimulated. “She was becoming a hermit,” says Thelma, “which wasn’t like her at all.”

Wilma is thus making a very smooth transition to her new life at the nursing home. She has difficulty striking up conversations with other residents, but she likes to be asked questions and will carry on a conversation if someone else starts it. Her favorite activity is reading, particularly books which have a religious theme, and she enjoys watching the news on TV. She also enjoys participating in any of the religious services or activities offered. Her family is very supportive and visit her often. Their mother, they say, has always been “a strong, kind-hearted woman who would do anything for anyone.”

(Originally written April 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post She Met Her Husband at the Candy Shop appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

December 24, 2020

“You Have to Stay Positive.”

Simona Novotny was born on November 25, 1901 in Blatnice, Czechoslovakia to Joseph Novotny and Pavla Adamik and was the youngest of nine children. Joseph was a flax farmer who routinely traveled to Germany in the off months to sell his flax. Simona says he made a good living this way because the Germans were eager to buy flax to make carpets “for the long winters.” Both of her parents were very healthy, Simona says, and lived into their nineties when they both died of “old age.”

Simona Novotny was born on November 25, 1901 in Blatnice, Czechoslovakia to Joseph Novotny and Pavla Adamik and was the youngest of nine children. Joseph was a flax farmer who routinely traveled to Germany in the off months to sell his flax. Simona says he made a good living this way because the Germans were eager to buy flax to make carpets “for the long winters.” Both of her parents were very healthy, Simona says, and lived into their nineties when they both died of “old age.”

Both of Simona’s brothers became butchers, and her six sisters all married tradesmen of some sort. Simona, however, after completing the eighth grade, wanted something else. She and her girlfriends wanted to go to America. Many people from her village had already made the journey, and, since she was the youngest of nine, Simona explains, her mother finally relented.

So it was, then, that the summer after Simona turned eighteen, she and four of her friends set sail for America. The sea voyage took twenty days. When they got to America, they made their way to Detroit, Michigan, where a sister of one of the girls lived. Simona quickly found a job as a maid in a church rectory.

Oddly, after only a couple of months of being in this new country, she happened to run into a young man she knew from her village of Blatnice. He was older than her and had been in the same class as one of her brothers. Simona didn’t know him all that well, but it was nice to see someone she recognized. His name was Joseph Novotny, the same as her father. Simona wasn’t too surprised by the coincidence of his name, as it is a very common one, she says, in Czechoslovakia. She was surprised, however, when Joseph asked her to marry him not long after they became reacquainted. “He was very persuasive,” says Simona, and, almost on impulse, she decided to take a chance and marry him. They went to the justice of the peace to get married, but later had their marriage blessed in the Catholic Church.

After only a few months, Joseph suggested they move to Chicago, where he said he had many friends. Simona wasn’t so sure she wanted to leave all of her friends, but she decided to trust Joseph and agreed to move to Chicago. As it turned out, they were quickly enveloped by the Czech community there, many people from their village having immigrated to Chicago after the war.

The Novotnys found an apartment on the northwest side, and Joseph got a job with a company that made auto parts for General Motors. Simona remained at home as a housewife and cared for their three sons: Frank, Joseph, and David. Simona was an avid gardener and was also very involved in her church, St. Sylvester’s, in Logan Square. She was part of the St. Vincent DePaul society and also the Altar and Rosary. She and Joseph never travelled much, except once to Detroit and once to Niagara Falls, preferring instead to stay at home.

Simona and Joseph apparently had a very happy marriage. They were a very social couple and had many friends. They often invited people over to their house for parties, and they always had a big Thanksgiving dinner, especially since it was usually on or around Simona’s birthday, and would invite lots of people from the neighborhood who had nowhere else to go.

The only real tragedy that befell the Novotnys was when their son, David, died at age twenty in a freak car crash. David’s death was particularly devastating to Simona because he was her favorite. She went into a depression for quite some time, but she eventually came out of it. “You have to stay positive, no matter what,” she says, even now. Her sons say that it was her intense faith that got her through that time, though how Joseph coped, they don’t know, as he refused to ever talk about David after the funeral. Simona, on the other hand, says that she takes comfort in knowing she will see David again someday in heaven.

In the early 1970’s, Joseph again persuaded Simona to move, this time to Union Pier, Michigan to retire. There they again made many friends, and Simona had a very big yard in which to garden, despite the fact that she had just turned seventy. After only four years of being there, however, Joseph died suddenly one morning of a heart attack while shoveling snow. He was seventy-eight. Simona remained in Union Pier for another sixteen years. Recently, however, at age ninety-two, she has become afraid to stay there any longer on her own. She is in remarkably good health, but she decided that she wanted to come back to Chicago and move into a Czech nursing home where her friend, a Mrs. Cerveny, resides.

Simona’s two sons, Frank and Joseph Jr., helped her to make the arrangements, and she is making a very smooth transition to nursing home life. She is extremely cheerful and positive and is enjoying having all of her meals prepared for her, especially some of her Czech favorites, though she says she herself makes them a little differently. Still, she says, she is grateful. She seems very interested in all of the activities the home has to offer, but so far spends most of her free time visiting and talking with Mrs. Cerveny, who is delighted to have her old friend back.

(Originally written: October 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post “You Have to Stay Positive.” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 17, 2020

From Mexican Theater Performer to Chicago Nanny

Eduardo Hernandez was born on November 7, 1922 in Mexico to Juan and Rosita Hernandez. Eduardo says that he was the youngest of seven children and that his mother died giving birth to him. His father worked as some type of laborer and, according to Eduardo, was a drunk who beat him and his siblings for even the smallest infraction. He was particularly hard on Eduardo, whom he constantly blamed for Rosita’s death.

Eduardo Hernandez was born on November 7, 1922 in Mexico to Juan and Rosita Hernandez. Eduardo says that he was the youngest of seven children and that his mother died giving birth to him. His father worked as some type of laborer and, according to Eduardo, was a drunk who beat him and his siblings for even the smallest infraction. He was particularly hard on Eduardo, whom he constantly blamed for Rosita’s death.

Eduardo did not go to school and spent most of his time roaming the streets and looking for work, though jobs were almost impossible to find. His family was “very, very poor,” Eduardo says, and adds that “Mexico was terrible then. You can’t imagine.”

Eventually, when Eduardo was thirteen or fourteen, he could no longer stand his father’s beatings, so he ran off with a theater group, where he spent many years dancing, singing, and performing with them. He lived a nomadic life, never having any money, but, at least with the theater group, he says, he had a place to stay, usually in tents, and a little bit of food. He repeatedly tried to find a more stable job, but there were very few of those. Finally, when he was in his early forties, he decided to try his luck in America.

Eduardo made it to San Antonio, where he found work in a kitchen. He didn’t like the work, but he did not have a lot of choices, he says, not only because he could he not speak English, but because he had never been to school and was ignorant of even the most basic of things. He worked in San Antonio for a long time and then made his way north to Chicago, where he again found work in various restaurants. On his days off, he would walk up and down State Street, marveling at the buildings and the people, and enjoyed taking everything in. One day he saw a “help wanted” sign in the window of a small hotel, so he went in and applied. The owner was a man named Robert Neilson, who would go on to become Eduardo’s lifelong friend.

After only three months of working in the kitchen of Robert’s hotel, Robert’s wife, Cathy, gave birth to a little girl, Amanda. The nanny that they had arranged to babysit her quit at the last minute, so the Neilsons asked Eduardo to fill in until they could hire someone new. Time passed, however, and soon the Neilsons and Amanda had grown attached to Eduardo, so they had him move in with them in their home in Park Ridge to become Amanda’s full-time nanny. Eduardo did this for the next ten years until Amanda didn’t really need a nanny anymore.

When it became evident that he was no longer needed, Eduardo moved out and found another restaurant job in the city, this one with an apartment above it, which he rented out for “next to nothing.” He never got married, he says, because he didn’t have enough money or a good enough job. For many years, he continued to visit the Neilsons, whom he says were like a family to him, and sometimes did odd jobs for Robert while there.

Several years after moving back to the city, Eduardo became good friends with one of his co-workers, a man several years his junior by the name of Enrique Garcia. Before long, Enrique offered to let Eduardo move in with him and his wife, Emily. Eduardo accepted and lived with the Garcia’s for about five years until he had a sort of stroke and was hospitalized.

After an extended stay in the hospital, Eduardo was discharged to a nursing home. He claims that he was told it would only be a temporary arrangement until he was well enough to go home. As the weeks progressed, however, Eduardo began to suspect that he was expected to permanently stay at the nursing home. He became extremely agitated and tried to walk out of the facility in an attempt to get back to Enrique’s apartment, telling the staff that Enrique was his son. When the staff tried to stop him, they claim he became violent and thus sent him to the psychiatric ward of a nearby hospital.

The hospital staff were eventually able to track down Robert Neilson, who then got involved in Eduardo’s plan of care. He helped the discharge staff to arrange for him to be released to a different nursing home. Robert says that he has a hard time believing that Eduardo became violent and is meanwhile trying to help him to make a better transition to this current facility. He says that Eduardo is “a good man at heart; he’s just a little crazy now.” Enrique also vouches for Eduardo, saying that he is a good man, but that caring for Eduardo in their home was becoming too much for him and his wife. They felt guilty when he was discharged to a nursing home, but relieved, as well. Robert has now listed himself as Eduardo’s official contact and says that he is committed to visiting him at least weekly.

Eduardo is making a relatively smooth transition. He does not exhibit any of the problem behaviors he supposedly engaged in at the previous nursing home, but he seems depressed much of the time. He speaks little English, so it is difficult for him to interact with the other residents. He spends most of his time in the day rooms watching TV or talking to any staff members who speak Spanish. They have asked him, from time to time, to sing some songs from his performing days, but Eduardo waves them away, saying that all of those things belong to the past. “I don’t remember,” he says dismally.

The only time he perks up is when Robert comes to visit. Recently, Robert surprised Eduardo by also bringing Amanda and her two children to the home to visit with him. Eduardo was absolutely delighted to see Amanda again and spent the afternoon showing them around, introducing Amanda to the staff as her “his girl” as often as he could. Since her visit, Eduardo has brightened considerably and continues to ask when his girl will return. (Originally written: March 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post From Mexican Theater Performer to Chicago Nanny appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

December 11, 2020

“One Christmas Left”

Angela Esposito was born on September 29, 1918 in Chicago. Her father, Leo Esposito, came to America as a young man from Florence, Italy. He made his way to Chicago and found work as a stone mason. After working as such for several years, he saved enough to open an ice cream parlor and made all the ice cream and candy himself. He met another Italian immigrant, Benigna Ricci, and they soon married in 1917.

Angela Esposito was born on September 29, 1918 in Chicago. Her father, Leo Esposito, came to America as a young man from Florence, Italy. He made his way to Chicago and found work as a stone mason. After working as such for several years, he saved enough to open an ice cream parlor and made all the ice cream and candy himself. He met another Italian immigrant, Benigna Ricci, and they soon married in 1917.

One year later, their first child, Angela, was born. The little family lived in Lakeview at Diversey and Wilbur, and it wasn’t until seven years later before another baby was born, Claudia. Angela and Claudia went to school in Lakeview and even attended high school.

Upon graduation, Angela got a job downtown as a secretary. Angela enjoyed her position, but after a few years, a friend encouraged her to look for work in the legal departments of companies because the salaries were higher. Angela, always shy and hesitant, deliberated this move for a long time, but then decided to take her friend’s advice. She switched to being a legal secretary and in that capacity worked for many years as a temp. This suited her because she made a lot more money, though she didn’t get benefits. Occasionally, a company she was temping for would offer a permanent position, and if she liked it, she took it.

Though she was “on the quiet side,” Angela was very social. She made some good friends at her various jobs and loved getting together with “the girls” after work. Their favorite activity was to go to dinner at the Italian Village and then head over to the Schubert or the Blackstone to see plays. Angela loved the theater and music of any kind. She also loved reading (mystery was her favorite!) and watching Westerns on TV. She also loved to play scrabble.

Though she had many friends and went out a lot, Angela never seemed to find a man she loved enough to marry, she says. There was one boy she met at school, but he was Polish. She didn’t think her parents would approve of him, so she never allowed a real relationship to develop. Angela says she went on a number of dates over the years, but she always had more fun with her girlfriends. Her parents were always offering to set her up with a nice Italian boy, but she always just laughed and said no.

As the years went on, however, her mother, Benigna, grew more and more impatient for a grandchild, so when Angela’s sister, Claudia, announced that she was getting married at age 23, Benigna was overjoyed. It was then that she confessed to Angela, simultaneously swearing her to secrecy, that she had recently been diagnosed with cancer. She kept it a secret from everyone, except Angela, and Leo, of course, until after the wedding when she had seen Claudia and her new husband off on their honeymoon to New Orleans. Later that same day, Leo drove her to the hospital for her first surgery.

Angela, still living at home, became her mother’s primary caregiver. Angela and her father spent the next year “watching Benigna waste away,” until she finally died at age 52 on Thanksgiving Day, 1949. Angela says that she has never since been able to enjoy Thanksgiving. Four years after her mother’s death, Leo, too, died from complications with diabetes. Claudia and her new husband had since moved to New Jersey, and Angela found that she did not like living in the family apartment alone. Accordingly, she decided to move into a hotel apartment nearby with a girlfriend from work.

Angela was happy there and stayed until the early 1960’s when she decided to get her own place and found a studio apartment in Rogers Park for $92 a month. She stayed there for fifteen years, but as the neighborhood grew more and more unsafe, she put her name on a waiting list for an apartment at North Park Village and moved to the northwest side for the interim. Finally, in 1990, she got a call saying that an apartment had opened up, and she moved in right away.

Angela enjoyed meeting her new neighbors and was able to live very independently for several years until she began to slow down in the summer of 1995 when she became very lethargic and lost a lot of weight. When she finally went to the doctor, she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She was hospitalized for about four weeks and then made the move to a nursing home with the help of the hospital discharge staff.

Fortunately, Angela has a nephew, Tom, living in Chicago, and he and his family have become very supportive of Angela. Claudia has long since passed away, so Tom is all she has. Tom and family visit often and are trying very hard to make Angela’s remaining time as pleasant as possible. Angela, for her part, says she has never handled stress well, but realizes that “crying and going into hysterics” in light of her prognosis, “isn’t going to help anything.” At times, she is very sad, especially as she realizes she only has “one Christmas left,” but she is trying hard to be positive. She is a very sweet, down-to-earth woman who always seems to have a kind word for those who stop to talk to her. The staff encourage her to mingle with the other residents, but she mostly prefers to stay in her own room.

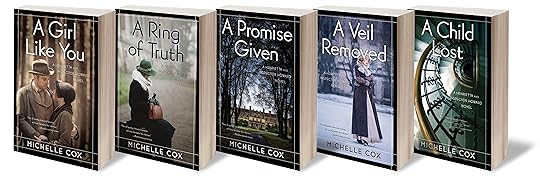

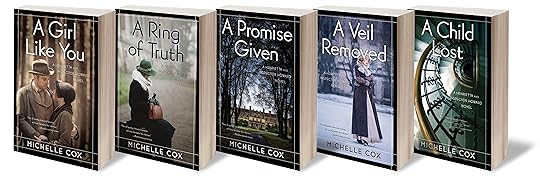

(Originally written December 1995)/(Photo: Angela Esposito, left)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post “One Christmas Left” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 3, 2020

“You Have to Make the Best of It”

Celeste Salvail (right) with her sister, Gina

Celeste Salvail was born on February 29, 1920 in Chicago to Vincenzo Salvail and Angela Potenza. Vincenzo and Angela were Italian immigrants who had met and married while still in Italy. In fact, they had already had two children, Apollonia and Christina, when they set sail for America, but Christina, who was just a baby, died on the voyage over. Vincenzo found a job in Chicago working for the railroads. It was his job to raise and lower the gates and to blow the whistle when a train was approaching. Angela was a housewife who cared for their nine children: Apollonia, Tito, Gina, Ines, Celeste, Manny, Silvio, Bianca and Rocco.

Unfortunately, when Celeste was still a baby, an accident occurred in which Celeste lost an eye. The family was at a 4th of July celebration, having a picnic outdoors. Some kids nearby were shooting off fireworks, one of which went out of control and exploded near baby Celeste’s face. As a result, she lost her left eye. She wore a patch over it until she was twenty, when she had an operation and was fitted with a glass eye.

Despite only having one eye, Celeste enjoyed school, though she was often teased. She also loved playing sports, especially with her brothers and sisters in the streets in their neighborhood. She was forced to quit school, however, after graduating from eighth grade, as the family needed money. Celeste found a job fairly quickly and says that she had so many jobs in her lifetime that she can’t remember them all. One of her favorites, though, was working on the assembly line at the Nabisco Cookie Company. Celeste worked there for sixteen years and was responsible for packing the cookies. She thought it was a very interesting job, and she really enjoyed it.

Celeste never married. She had a boyfriend, Alfred, for many years and says that she was in love with him. He asked her to marry him, but she turned him down in the end and broke off their relationship. “He was an alcoholic,” she says. Though she loved him, she was afraid of what a marriage to him might mean and that she would end up supporting him and any children they might have. After that, she “tried to get a rich one,” she jokes, “but they were hard to come by!”

Celeste remained single and devoted herself to her nieces and nephews. Her parents died relatively young: Vincenzo of double pneumonia and Angela of a heart attack. For a long time, Celeste lived with her sister, Ines. She loved to garden and to spend time with her family playing games. Later in life, she lamented the “good ole days,” when she would take her nieces and nephews on a picnic virtually every weekend of the summer.

In the mid 1980’s, Ines unfortunately passed away, so Celeste got her own place, where she lived alone for many years. Eventually all of Celeste’s siblings passed away except Biance, who continued, with the help of her daughter, Juday, to check in on Celeste. In December of 1993, Celeste fell and broke her hip and was hospitalized for over a month, where she was a very willing participant in physical therapy and social activities. It was decided, then, between the discharge staff at the hospital, Bianca, and Celeste that she would be admitted to a nursing home, at least to continue her physical therapy.

After being here for several weeks, however, Celeste is accepting that this is now her permanent home and is working hard at making a smooth transition. She has a very positive attitude and says “you have to make the best of it”—a mantra she seems to have adopted early in life. She has made several friends already and enjoys, in particular, exercise class, arts and crafts, bingo and smoking cigarettes in the smoking room. She also says she would be interested in helping with the gardens in the spring.

Bianca and Judy, as well as many of her other nieces and nephews, come to visit her often and have been extremely loving and supportive of their aunt/great aunt. “There’s no use crying over spilled milk,” Celeste says, “you just have to keep trying.”

(Originally written January 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post “You Have to Make the Best of It” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 26, 2020

Otto and the Cross-Country Journey to Get Back “Their Girls”

Otto Hutmacher was born on November 12, 1907 in Prussia to Poldi and Magda Hutmacher. Poldi was a carpenter, and Magda cared for their eight children. Otto only went to the equivalent of grade school and then got a job driving a team of horses for the government. “It was a life of starvation,” he says, so at age 23, he ran off to join his brother, Ernest, in America. Ernest and his wife, Marie, had already immigrated several years before and had written letters to tell the family that there were many jobs. Poldi refused to leave, however, and when Magda tried to plead with him, he beat her. All of his brothers lived in fear of Poldi, so Otto took off by himself to make the journey to America.

Otto Hutmacher was born on November 12, 1907 in Prussia to Poldi and Magda Hutmacher. Poldi was a carpenter, and Magda cared for their eight children. Otto only went to the equivalent of grade school and then got a job driving a team of horses for the government. “It was a life of starvation,” he says, so at age 23, he ran off to join his brother, Ernest, in America. Ernest and his wife, Marie, had already immigrated several years before and had written letters to tell the family that there were many jobs. Poldi refused to leave, however, and when Magda tried to plead with him, he beat her. All of his brothers lived in fear of Poldi, so Otto took off by himself to make the journey to America.

Once here, he found Ernest and Marie in Chicago, where they had already saved enough to buy a house. One by one, the siblings eventually all came, though Poldi and Magda stayed and eventually died in Germany.

Otto was able to immediately find a job at the Continental Can Company, where he worked for eight years. From there, he got a job at a place called Goodmans, which was a tannery. Otto enjoyed this work and stayed at Goodmans for over thirty years.

In his forties, Otto met a woman “from the neighborhood,” which was Southport and Clybourn, at a bowling alley—Otto’s one hobby. Vera Rudaski had been born in Poland and had immigrated here as a young girl. She received little schooling and worked in a variety of factories around the city. Otto finally worked up the courage to ask her out, and they began dating. He was shocked, however, when he stopped by her house one day as a surprise, to find two young girls living there with her.

It was then that Vera reluctantly explained to him that she had gotten pregnant when she was only seventeen and had a baby, Dorothy. The father of the baby abandoned Vera, and she never married. She was forced to then raise Dorothy on her own, as her parents would have nothing to do with her after they discovered she was pregnant out of wedlock. It was a difficult road, Vera told him, and Dorothy was often left alone at home while Vera worked. As she got older, Dorothy began to get into trouble, and Vera found it hard to control her as the years went on.

Vera was heartbroken, then, when Dorothy came home one day and told her she was pregnant. Vera tried to convince Dorothy to give the baby up for adoption, knowing firsthand how difficult it was to raise a baby alone, but Dorothy just laughed and said that that was what mothers were for. She wouldn’t hear of giving up her baby, especially after she unexpectedly gave birth to twin girls, whom she named Flora and Fern. Vera saw no choice but to help Dorothy care for the babies as much as she could, but it was difficult to do while still working.

To make things worse, when the twins were just over a year old, Vera came home from work one day to find the twins crying in their crib and Dorothy gone. Vera found a note from Dorothy which said that she was leaving with a boyfriend for Las Vegas and that she would be back when she had made some money. At that point, Vera didn’t have the heart to put the twins in an orphanage, so she struggled along as best she could. Only periodically did she ever receive a letter from Dorothy, but never with any money enclosed.

After Otto discovered the twins at Vera’s house, he asked her why she hadn’t told him about the girls in the first place. Vera replied that she didn’t think he would be interested in her if he knew she had little kids to take care of. Otto’s response was to ask Vera to marry him. She happily accepted, and he moved into the house with Vera and “their girls.” At the time, Flora and Fauna were six years old, and they took to Otto right away. The girls called Vera and Otto “mom” and “dad,” which suited the two of them fine. Vera was too old to have any more children, so they both enjoyed the girls as if they were their own.

Things went along well enough until, sadly, Dorothy reappeared on the scene out of the blue when the girls were just eleven years old. She had a new husband, Bill, she said, who had convinced her to come back and get the girls to live with them in Vegas. Not only was Dorothy angered by the girls’ shy reception of her, but she was outraged when she heard them calling Vera “mom” instead of “grandma.” Hurriedly she packed them up and took off with them, though Flora and Fern screamed and cried at being removed from Vera and Otto. Otto tried everything in his power to convince Dorothy to change her mind, but to no avail.

The girls stayed with Dorothy and their step-father, Bill, for almost a year, writing home constantly, saying that they were miserable. Their step-father was almost always drunk, they said, and they were afraid of him. Likewise, Dorothy had yet to enroll them in school.

Meanwhile, with every month that passed, Vera sank deeper into depression. Nothing seemed to interest or rouse her. It was at that point that Otto decided to take matters into his own hands and planned a trip across the country to Las Vegas to try to get their girls back. He eventually found Dorothy and the girls living in a filthy apartment, just as the girls had described in their letters. He offered Dorothy and Bill all of his savings in the bank if they would agree to let them have the girls back.

Bill, deeply in debt, agreed, and even Dorothy, though she protested some, didn’t seem to mind that much. Otto, on the other hand, was overjoyed. He drove almost non-stop to get back to Chicago and Vera.

When they arrived, Vera was beside herself with joy, but she was worried about what the girls must have been through with Dorothy and Bill. Likewise, while the girls were happy and relieved to be back home, they were not quite the same as they had once been. They were quieter now and more distrustful.

Things eventually progressed, however, and life went back to normal as much as possible. Otto and Vera had few hobbies and wanted to spend any free time at home with their girls. Flora and Fern eventually went to high school and then got married. Otto and Vera took a couple of trips when they retired, but they mostly stayed at home and enjoyed spending time with Flora and Fern’s children, whom they called their grandchildren, though they were really Vera’s great-grandchildren.

Otto and Vera lived on their own in the same house until 1992, when Vera died peacefully at age 85. Otto was able to care for himself for a while before he started to get very confused and wander. After he was repeatedly found lost in the neighborhood, Fern took him in for a time. When she herself was recently diagnosed with cancer, however, and it became too much for her to care for him as well. With a heavy heart, then, the girls—now getting up there in years themselves, placed Otto in a nursing home.

Otto seemed to be make the transition well at the beginning and enjoyed many of the activities involving music in particular, but he has since begun to decline a great deal. He is now confused and disoriented most of the time and sometimes does not even recognize Flora or Fern when they come to visit. Often he makes nonsensical comments, such as “I won’t die because I live in a mountain.” It makes Flora and Fern very sad to see him this way, but they are happy he is being cared for, and often bring the grandchildren to see him.

(Originally written June 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post Otto and the Cross-Country Journey to Get Back “Their Girls” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

November 19, 2020

A Postal Theft, Two Vaudeville Actors, an Unsolved Murder, a Little Girl, and The Best Thing That Ever Happened!

Andrew Pokorny was born on October 20, 1912 in Chicago to Branislav Pokorny and Maria Tesar, both of whom were immigrants from Slovakia. Andrew is not sure whether his parents met and married in Slovakia or if they met here, but he remembers his father working as a coppersmith. His mother was a housewife and cared for their three children: Andrew, Danka and Martina.

Andrew Pokorny was born on October 20, 1912 in Chicago to Branislav Pokorny and Maria Tesar, both of whom were immigrants from Slovakia. Andrew is not sure whether his parents met and married in Slovakia or if they met here, but he remembers his father working as a coppersmith. His mother was a housewife and cared for their three children: Andrew, Danka and Martina.

The Pokornys lived in various apartments on Chicago’s north side and never did own their own home. Andrew went to school until the seventh grade and then began working. He jumped from job to job, mostly in factories or sometimes as a delivery boy. Though he had quit school early, he was clever, and he eventually found himself working at the post office in the mail room. This was a job Andrew really enjoyed, and he was proud to have it. His goal was to eventually be promoted to mail carrier, so he worked hard and tried to learn as much as he could.

On his days off, Andrew was fond of riding his bicycle around the city and in some of the city’s bigger parks, like Humboldt, Garfield and Douglas. One day, as he was riding through Garfield Park, he came upon a young woman sitting on a bench knitting. He stopped to ask her name, and they began talking. From there they began dating, and a year later, Andrew and Elizabeth Newman were married. Andrew had been raised Lutheran, and Elizabeth was Catholic, so Andrew converted to Catholicism for the wedding. He took it seriously, though, and remained devoutly Catholic his whole life. Elizabeth worked at Marshall Fields behind the cosmetics counter, with the understanding that when she became pregnant, she would quit to stay home and be a housewife. Sadly for both of them, however, they were never able to have children.

When they eventually realized that they were probably not going to have a family, Andrew and Elizabeth tried instead to get involved in their parish and joined various bowling leagues over the years. They also loved going to the movies and baseball games. Neither of them, it seemed, liked the idea of traveling.

Things stayed this way for about ten years and may have continued as such had a crisis not occurred at Andrew’s place of work, which was still the post office. Unbeknownst to Andrew, his best friend at work, a man by the name of John Davis, had been stealing mail for years. He was finally caught and arrested, and Andrew, by association, was suspected as well and was fired pending an investigation. John Davis ended up going to jail, while Andrew was cleared of any wrong-doing. He permanently lost his job, though, and thus his hopes of a career in the postal service.

Andrew began drinking heavily to deal with his grief over losing his job and could not seem to find another. After a couple of years of this, Elizabeth announced that she was divorcing him. She had run into an old boyfriend, she said, and was leaving Andrew for him. Andrew begged her not to go, but she eventually moved out of the apartment, remarried, and went to live with her new husband in Wisconsin.

With no job and no money, Andrew was forced to leave the apartment, too, and moved into a cheap motel. His sister, Danka, had died of cancer several years before, and he had been estranged from Martina from a young age. “We never got along,” Andrew says and lost touch with her when they were in their twenties. Even now, he has no idea where she is or if she is even alive. Thus, at the time of his divorce, he was very alone and really had nobody. He had lost his best friend, his job, his wife, and all of his immediate family. He got odd jobs here and there, enough to buy cigarettes and alcohol with, but not much more.

Andrew was eventually befriended by his next-door neighbors at the motel, a couple called Leo and Nellie, who claimed they had once been vaudeville entertainers and that they still made most of their money by acting or performing in various travelling shows. Andrew had never met anyone like them and was amazed by their talents. He loved it when they showed him magic tricks or did their juggling routine for him, and he especially took a shine to their little daughter, Josephine, or “Josie.”

Over the next several years, Andrew got to know his neighbors well and often even babysat for Josie when Leo and Nellie were travelling. One summer, however, Leo and Nellie did not come home, and Andrew later learned that they had been both been killed, apparently murdered. Leo and Nellie’s deaths were never solved, but Andrew thinks that it might have had something to do with gambling. Andrew took Josie in, though she was already fourteen at the time, and found it difficult to control the grieving, rebellious girl.

When she was just sixteen, Josie got pregnant and moved into her boyfriend’s apartment because Andrew was drinking so heavily. She had the baby, a little boy she named Leo, but she became quickly disillusioned with her relationship with her boyfriend. Eventually she went back to Andrew’s, with the baby on her hip, as Andrew now tells the story, and demanded that he choose between “the bottle” and them.

Andrew, astonished that Josie had returned, says that he gave up drinking and smoking from that day forward. He sobered up, got a job as a punch press operator, and moved into a decent apartment. Josie and little Leo stayed with him for several years until Josie met someone new and got married. They moved into their own apartment nearby on Pulaski, and Josie had two more children. She and Andrew stayed very close, however. Andrew says she is like a daughter to him, and, in turn, Josie refers to him as “Pops.” Andrew says he is so very thankful that he made the choice he did and that Josie didn’t give up on him.

Andrew was able to live on his own until 1992, when Josie found him unconscious on the floor of his apartment. She called an ambulance, and he was diagnosed as having had a stroke. He was then admitted to a neighborhood nursing home near where Josie and her family still live.

Andrew has made a brilliant transition to the home and often says, “This is the best thing that ever happened to me.” He fully participates in every activity the home provides, and Josie and her children often come and volunteer, of which Andrew is very proud. His favorite duty is calling the bingo numbers. Besides helping with activities and visiting residents who are bed-bound, each day he sits near the entrance of the home and greets people as they come in. He is so helpful to visitors coming in, as well as to current residents, that the staff had a badge made for him, designating him as a top volunteer and ambassador to the home. He is extremely proud of his badge and wears it everywhere. He is a wonderful example of someone who turned his life around, albeit a bit late, for the benefit of not only himself, but of many. He is very much an inspiration to all who are lucky enough to know him.

(Originally written: May 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post A Postal Theft, Two Vaudeville Actors, an Unsolved Murder, a Little Girl, and The Best Thing That Ever Happened! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

October 29, 2020

“Charlie Was the Love of My Life.”

Louisa Berger was born on September 5, 1907 in Macedonia. Her parents, Martin Everhart and Liese Buhr were German farmers living in what was once called the Austro-Hungarian Empire in an area that later became Yugoslavia. There were originally nine children in the family, but three of them died of diphtheria. The rest of them worked very hard on the farm and suffered much under the hand of Martin, who was “a mean, cruel drunk,” whom they all hated. They lived in horrible poverty as things in Europe got progressively worse. At some point, Martin decided to abandon his miserable farm and immigrate to the United States, taking the family with him.

Louisa Berger was born on September 5, 1907 in Macedonia. Her parents, Martin Everhart and Liese Buhr were German farmers living in what was once called the Austro-Hungarian Empire in an area that later became Yugoslavia. There were originally nine children in the family, but three of them died of diphtheria. The rest of them worked very hard on the farm and suffered much under the hand of Martin, who was “a mean, cruel drunk,” whom they all hated. They lived in horrible poverty as things in Europe got progressively worse. At some point, Martin decided to abandon his miserable farm and immigrate to the United States, taking the family with him.

Louisa was just a small girl at the time, though she says she remembers the ship. Upon arrival in New York, the Berger family made their way to Chicago, where Martin had a cousin. He was able to find some work in a factory, but after about a year, he took the family to Minnesota, where they worked on a beet farm for many years. Martin eventually abandoned this, too, and again moved them all back to Chicago.

By this time, Louisa was roughly fourteen years old and had received almost no schooling. She got a job in a candy factory in Chicago and worked many hours to bring in money for her family. Louisa describes herself as being very shy back then, but that she managed to make a few friends at work. Louisa and her friends made it their routine to walk every Sunday in Humboldt Park, where they loved to hear the bands play in the band shell. On one of these Sundays, Louisa met a young man by the name of Charlie Berger, who was also walking in the park with friends. Charlie, Louisa says, was very outgoing and easy to talk to. “Before I knew it,” she says, “I was on a date with him, and I didn’t even realize it!”

Charlie worked as a shoemaker, and the two of them married when Louisa was seventeen. They lived on the north side, and Charlie went to night school to become a realtor. Louisa continued working at the candy factory until she got pregnant. Together they had five children: Charles Jr., Clarence, Carl, Lillian and Irene. Once the children were older, Louisa sometimes worked as a cleaner in the evenings. “Charlie was the love of my life,” Louisa says. They were never separated except for when he served in the army during the war.

Louisa says she led a very simple life and didn’t go out much. “I never wanted to,” she says. She was happy listening to music and was mesmerized when they got a television. Most of her time, though, was spent gardening and baking. Charlie dug up almost the whole back yard for her to plant as a garden, and she often won prizes for her vegetables and flowers. “She was always baking,” says her daughter, Irene. Even after they all left, she would still bake several pies and cakes each week and bring them to church meetings or to the rectory for the priests to eat. She looked forward to Sundays when her two sisters would come over and they would play cards all afternoon.

Having never gone to school, Louisa was basically illiterate for most of her life, something she was very ashamed of. Charlie tried to teach her to read in the early years of their marriage, but it proved difficult for him to find the time between working and going to night school. Louisa, too, was busy with the five children and likewise couldn’t make learning to read her priority. Instead, Charlie took care of everything—all of the bills and finances and correspondences.

It was a particularly crushing blow, then, when Charlie fell off a ladder and died at age fifty-two. Louisa’s children stepped in to help her as much as possible, though most of them were already gone. Carl was still at home, though, and it was he that was successful in finally teaching Louisa to read. Louisa delighted in being able to read the newspaper, but it was short-lived, however, when she began to go blind several years later. Though she can still see a little bit, she has been declared legally blind and must now use a cane.

Remarkably, however, Louisa continued to live independently until about two years ago when she turned eighty-nine and began needing more help. Irene, Carl and Lillian, the only children still in the area, tried taking turns going to assist her, but they are themselves somewhat advanced in years now, with various health problems and their own families to worry about. When it got to be too much to constantly go and check on her, they hired a caretaker to come in periodically and even tried adult daycare. Both of these things helped, but they did not prevent her from repeatedly falling when she was alone.

After a particularly bad fall, Louisa ended up in the hospital and became very disoriented, which prompted the hospital staff to recommend that she be discharged to a nursing home. Her children were reluctant to do so, but, ultimately, they felt it would probably be for the best considering her condition.

Louisa is adjusting to her new surroundings, but she is frequently confused about where she is and often asks for Carl or sometimes even her husband, Charlie. At other times, however, she is very clear and likes answering questions about her past. It is difficult for her to participate in activities because of her poor eyesight. She refers to sit amongst the other residents, however, rather than be alone in her room.

(Originally written: September 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post “Charlie Was the Love of My Life.” appeared first on Michelle Cox.