Michelle Cox's Blog

July 16, 2025

A Sister’s Devotion

Esther Matula was born in Chicago on August 13, 1929 to George Matula and Nicola Pacek, both of whom were children of Bohemian immigrants. George was born in Chicago and worked as a “heat treater” in a tool factory, and Nicola, who was born in Rice Lake, Wisconsin, cared for their four children: Vincent, Esther, Darlene and Herman. From time to time, Nicola helped out at the corner grocery store for extra money, but she was frequently ill and in and out of the hospital so often that she didn’t earn much.

Esther was always been considered to be “mentally retarded,” but Esther’s younger sister, Darlene, believes that Esther was actually born a “normal little girl.” As a young adult, Darlene spent a lot of time questioning various aunts and uncles and cousins about her older sister’s early years and has concluded that Esther was not born “retarded” as everyone has always labeled her. Darlene discovered that one fateful day when her mother went out, Nicola put George in charge of watching the children, which, at the time, was just Vincent and Esther, who was only a toddler. Apparently George got drunk, as usual, though he promised Nicola that he would not, and left the cellar door open. Esther wandered by and fell down the stairs, which is apparently when her “retardation” began.

The obvious person to ask the truth would of course have been Nicola, but she unfortunately died at the young age of 38. Always ill, Nicola’s doctor finally diagnosed her with a “poisonous, inward-growing goiter” and told her that she did not have long to live. Informed with this tragic information, Nicola knew she had to make a very difficult decision. She knew she could not leave Esther, who was just thirteen at the time, with George after she was gone, as, not only was George an alcoholic, but he was cruel to Esther as well, constantly teasing her and threatening to cut off all her hair, which never failed to throw Esther into hysterics. So before she died, Nicola packed up Esther and took her to a mental institution, where she felt she had no choice but to leave her, despite Esther’s screams to not be left behind.

Nicola returned home, utterly depressed, and was not long after again admitted to the hospital. She did not expect to ever go home again. Surprisingly, however, Nicola was eventually released. When she returned home and found George drunk again, something snapped inside her, apparently, and she flew into a rage. Darlene remembers that day—her mother yelling and screaming until she eventually collapsed in front of them, dead of a cerebral hemorrhage.

The day after Nicola’s funeral, Vincent, just seventeen, declared that he wasn’t going to “get stuck washing dishes and caring for brats” and left to join the navy. Darlene was eleven, and Herman was ten. Esther, of course, was still in an instituion.

Though Nicola had placed Esther at a Catholic facility in the city, the staff there eventually transferred the girl to the mental asylum in Dixon, Il., where she lost contact with her family for many years. Darlene eventually married and moved to Arkansas, but she always felt guilty about leaving Esther behind in Illinois. Over the years, however, Darlene has been able to communicate with Esther over the telephone. The first time Darlene called her, Esther supposedly recognized Darlene’s voice instantly before Darlene even had a chance to explain who she was. Esther was reportedly overjoyed to hear from her sister.

After that, Darlene tried to get her brothers to call Esther as well, but both refused, saying that Esther wouldn’t remember them anyway. Darlene has tried many times to explain to them that Esther does in fact remember them and that she asks about them during every single phone call. Darlene has also told them that, amazingly, Esther remembers many family members and stories from way back. Still, Vincent and Herman have refused to call Esther even once. Darlene suspects that they feel too guilty, especially after she related to them a story told to her by an aunt—that despite her damaged mind, Esther loved her siblings very much and was very protective of them even up to the day she was taken away.

When she reached her sixties, Esther was transferred to various nursing homes that could better care for her until she was finally placed in a facility called “Our Special Place,” which was a community house for seniors with mental disabilities. Esther apparently loved “Our Special Place,” the first “home” she had lived in since age thirteen. Esther stayed there for several years until she began having seizures and had to have brain surgery. Upon being released from the hospital, she was required to go to a rehabilitive nursing home to recover, which has been very disorienting and upsetting to her.

Though Esther is officially under the care of a state-appointed guardian, Darlene has been kept informed of her progress. She is very distraught at the thought that Esther had to leave “Our Special Place,” and is trying to convince Esther’s guardian to let Esther go to Arkansas to be near her. Darlene hopes that Esther can come to live with her, but as Darlene is now legally blind and is also diabetic, this does not seem to be a realistic plan.

Meanwhile, Esther is not making a smooth transition. She is not able to communicate effectively with other residents and has no desire to participate in activities. Her only solace is listening to music. Darlene calls her every other day, but Esther finds it difficult to talk.

(Originally written: November 1996)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post A Sister’s Devotion appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

June 19, 2025

From Ukrainian Professor of Physics to Janitor

Sasha Pasternak was born on March 12, 1946 in Ukraine. His parents were Martyn Pasternak and Alberta Jelen. Jelen, Sasha reports, means “stag” in Polish, and he seems very proud of his mother’s name.

Sasha Pasternak was born on March 12, 1946 in Ukraine. His parents were Martyn Pasternak and Alberta Jelen. Jelen, Sasha reports, means “stag” in Polish, and he seems very proud of his mother’s name.

Martyn was a Ukrainian Jew, and Alberta was a Polish nurse living in Ukraine with an elderly woman she was hired to care for. As it happened, the elderly woman’s children and grandchildren often came to see her, and one day one of her grandson’s brought a friend along by the name of Martyn Pasternak. As soon as Martyn saw Alberta, he fell in love with her, and they married in 1928. Martyn worked as an economist, and Alberta continued working as a nurse until their first child, Anna, was born in 1932.

Fourteen years later, in 1946, a son was born – Sasha. Sasha attended high school and university, eventually becoming a professor of physics, with a specialty in medical radiation. He was on the chief of staff in this field, did extensive research, and gave lectures at the university in the evenings, enjoying his career immensely.

In 1969, when he was 23, he married the love of his life, Liliya. As it happened, however, he had been dating a different girl, Vira, shortly before he met Liliya. One night, he and Vira went to a friend’s apartment to celebrate Vira’s birthday. At the impromptu party, Sasha was introduced to his friend’s date, Liliya, and instantly fell in love with her, perhaps in the same way his father, Martyn, had fallen in love with his mother, Alberta. Ten days after Vira’s birthday party, Sasha married Liliya in a quiet service.

Sasha and Liliya, who worked as a language teacher, made a happy life for themselves in Ukraine and had two sons: Ivan and Denys. Sasha says he left the Communists to themselves and lived his own life. He felt he had a pretty good salary, a great job, a nice family and a nice apartment. When Communism fell, however, his life began to fall apart. His salary shrank to almost nothing and his sons, just leaving university, had no job prospects. Seeing the situation in the Ukraine as hopeless, Sasha decided to move the family to America and arrived in Chicago in 1994 with Ivan and his wife and daughter; Denys; and Liliya’s parents. And while there proved to be much more opportunity for their sons, Sasha and Liliya’s prospects worsened. Sasha gave up his brilliant career in research to become a janitor, and Liliya found a job at the counter of Lord and Taylor.

After about a year in America, the powers that be at Evanston Hospital where Sasha worked as a janitor learned of his background in the Ukraine and offered to send him through 14 months of training in medical radiation. In exchange for the free training, he would continue working as a janitor, but would not get paid for it. Sasha thought much about the offer. He desperately wanted to take it, but he eventually declined, as he calculated that the family could not exist for fourteen months without his salary. For one thing, shortly after their arrival in America, Liliya’s parents began to have a myriad of health problems. Her father had to have a lung operation and his leg amputated, which required extensive hospitalization. In order to visit him every day, Liliya’s mother had to take three buses to get to the hospital, and eventually the stress got to her. She had a heart attack and then a series of strokes and falls before she finally died.

Sasha was eventually offered a the position of lab technician, which brought in more money than he had made as a janitor, but the family still struggled because Liliya had been forced to quit her job to take care of her parents when they were ill and dying. As luck would have it, things got even worse for the Pasternak’s. In October of 1996, just as Liliya was getting over the death of her father, Sasha was hit by a car. He spent eighteen days in the hospital before he was transferred to a nursing home to more fully recover. Upon his admission, he had a lot of anxiety and found it difficult to lie in bed all day. He has since begun to be up and about more and looks forward to Liliya and his sons coming to visit each day. He is eager to get home and back to work, he frequently repeats, though he worries that his job will be given to someone else. His boss, he says, has promised to hold his job, but, Sasha says, “I am a pessimist at heart. I wait and see.”

(Originally written: October 1996)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post From Ukrainian Professor of Physics to Janitor appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 1, 2025

The Maid, the Asylum, and the Old Cubs Field

Agnes Faraldo was born on April 11, 1917 in Chicago to Feodor Ciesielski and Vera Bergmann. Both Feodor and Vera were born in Chicago, though Feodor’s family came from Poland and Vera’s from Germany. Feodor was one of fourteen children and had little schooling. He worked as an usher in a movie theater, which is where he met Vera, the concessions girl. Years and years later, Agnes discovered that when her parents got married, Vera was already seven months pregnant with her!

After they got married, Feodor quit his job at the movie theater and got a job as an electrician. They moved from apartment to apartment in the Milwaukee, Belmont and Western area of the city, and Vera had three more children: Polly, Bud, and Wilson. As time went on, Feodor began to drink heavily and became an alcoholic. He and Vera’s marriage, never a happy one, as it turned out, disintegrated completely when Vera went to live with another man by the name of Oscar Schaffer and took the children with her.

Any hopes that Agnes had that their life would be better with Oscar were quickly dashed. She quickly grew to hate Oscar, though she does not say why, but her mother seemed content to stay with him. Vera lived with him for twelve years before finally getting married to him. Feodor, meanwhile, later died in the TB ward of Cook County Hospital in 1942, a “broken-down alcoholic.”

Agnes quit school after seventh grade to get a job and desperately wanted to move out on her own after the family moved in with Oscar. Vera refused to let her, though, until she turned eighteen. When her eighteenth birthday finally came, she left and took a job as a maid for a wealthy family, which provided room and board. She stayed away from the family for almost a year before being persuaded by her sister, Polly, to come home to help celebrate their brother, Wilson’s, graduation. Agnes agreed and at the party was introduced to Polly’s boyfriend, a man by the name of Vince Faraldo, whom she was instantly attracted to. When Vince asked her out the very next day, Agnes agreed, but was wracked with guilt that she was betraying Polly.

Vince and Agnes really hit it off, but Agnes worried about what kind of man would switch his affections so easily, especially between sisters. Vince managed to convince her, though, that he had only recently met Polly and that she was more of a friend than anything else. When Agnes finally worked up the courage to tell Polly how she felt about Vince, Polly didn’t seem to mind at all. “He’s not that great. You can have him!” Polly supposedly told her.

With Polly’s blessing, then, the young couple began dating and married in 1939. Agnes quit her job as a maid and became a housewife. When they met, Vince had a job delivering coal and ice, but after they got married, he began working for the B & O Railroad and finally ended up as a cement mason. Their first baby, Anthony, was born in 1940, and two years later, Rosamund, was born. When the World War II broke out shortly thereafter, Agnes and Vince made a conscious decision not to have any more children. Fortunately, Vince did not have to serve in the army because he had stomach ulcers.

Agnes and Vince first lived in an apartment near 12th and Taylor, close to where Vera lived and a year later moved to May St. and Polk, which was where Anthony was born. From there they moved to Hermitage and Taylor, where they remained for eight years until they eventually had to vacate their apartment because the University of Illinois Hospital was buying up land in the area to expand their campus.

Agnes has an interesting story about that area of the city and enjoys sharing it with anyone willing to listen. According to her, in 1917, the same hospital bought up the nearby, vacated Chicago Cubs ballpark, also known as West Side Park, which was located at Polk and Wolcott and which was where the Cubs won two World Series championships. At the time that it was still being used as a ball park, however, there happened to be an insane asylum located just past the left field fence. Agnes says that it is common knowledge that during the games, the inmates of the asylum used to scream crazy things out of the windows, which is supposedly where the phrase “that came out of left field” originated!

At any rate, Agnes and Vince were thus forced to leave the area and moved north to Division Street, just across from Humboldt Park , where they stayed in a friend’s basement apartment until they could find something better. Agnes says that it was hard to find a place in those days and that many did not like children. They eventually did find a place down the street on Division and stayed there for fifteen years. Then they moved to Drake and Belmont and stayed there for another twenty years until Vince died of cancer in 1984.

After Vince passed away, Agnes lived on her own until her eyesight began to get bad. Her daughter, Rosamund, persuaded her to come and live with her in Antioch, Illinois, very far north of the city. Agnes stayed there for two years and enjoyed being with family, but in the end, she missed the city too much and decided to go back, much to the family’s dismay. They helped her, however, to move into a basement apartment on Montrose, where she remained for one year before moving to Forest Preserve Drive.

Needless to say, Agnes was a very independent woman and was able to care for herself relatively well despite her failing eyesight. When she was nearly hit by a car when attempting to cross the street, however, she began to become frightened of leaving her apartment at all. She became depressed and reclusive, so Rosamund and Anthony decided to intervene. Anthony told her that his mother-in-law had just gone to live in a nursing home on the NW side and that she really liked it. Curious, Agnes agreed to visit it and also really liked what she saw. She agreed that it would be the best, safest place for her and so, one more time, perhaps her last, she moved.

Agnes is adjusting very well to her new home and is very eager to meet people and to help out all she can. Currently she enjoys helping the staff fold laundry and has joined many activities. She loves smoking with her fellow residents in the smoking lounge, and has a wonderful sense of humor. She says that her hobby used to be embroidery, but since she can no longer do that because of her eyes, she is hoping that she can find some new hobbies at the home! Agnes has a real zest for life and is a very fun person to converse with and be around. She has quickly become a favorite among her fellow residents.

(Originally written: July 1994)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post The Maid, the Asylum, and the Old Cubs Field appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 24, 2025

“So Damned Mediocre!”

Leona Wilson was born in Oklahoma on December 16, 1906 to Nigel Wilson and Elizabeth D’Evers. Nigel was born in England and had a passion for the American Wild West since the time he was a little boy. So strong was his desire to be a cowboy that he ran away from home as a teenager and got a job on a ranch in Colorado. His father eventually tracked him down and made him return to England to finish his education, promising that once he did so, he would be free to do as he liked.

Leona Wilson was born in Oklahoma on December 16, 1906 to Nigel Wilson and Elizabeth D’Evers. Nigel was born in England and had a passion for the American Wild West since the time he was a little boy. So strong was his desire to be a cowboy that he ran away from home as a teenager and got a job on a ranch in Colorado. His father eventually tracked him down and made him return to England to finish his education, promising that once he did so, he would be free to do as he liked.

Nigel accordingly graduated from university with a degree in business and immediately returned to America. He first went to Chicago, where he met a young woman, Elizabeth D’Evers, at the Presbyterian Church he was attending. The two of them began dating while Nigel worked in an accounting firm to earn money to go back out west. Eventually, Nigel and Elizabeth married and had two children, Edmund and Gerald, before they had finally saved enough money to buy a ranch in Oklahoma.

Once settled in Oklahoma, the Wilsons had three more children: Margaret, Leona and Catherine. Leona says that Margaret was her “mother’s pet” and could do no wrong. She was very spoiled, and, consequently, Leona hated her. The Wilson’s remained on the ranch for about ten years before Nigel decided he had had enough. Somehow, ranch life was harder than he had remembered it being as a boy. The family moved again, this time to Denver, where another baby, Herbert, was born. Leona says that she hated Herbert more than she hated Margaret, as he was “a terrible brat and annoyed everyone.”

Leona reports that she had a tolerably good childhood. Her family, she says, wasn’t terrible; their great sin was that they were “so damned mediocre.” She carries a bit of a chip on her shoulder, however, as she feels like she was pretty much ignored and even cheated by her parents. Margaret and Herbert, she says, got everything they wanted, while “I was given nothing,” she says.

Leona remembers begging her parents for violin lessons, for example, but they refused to waste money on such a thing. Later, she begged for art lessons, but they again “ignored me and never encouraged me at all!”

After Leona finished elementary school, Nigel and Elizabeth decided to divorce. Leona is not sure why, but she thinks it might have been because Elizabeth wanted to move back to “civilization.” Thus Elizabeth took the three girls and Herbert and returned to Chicago, while Nigel and the two oldest boys remained in Colorado.

Elizabeth and the children moved in with her parents, the D’Evers, and Leona started high school. She eventually graduated and then begged to be allowed to attend the Art Institute, but Elizabeth and her well-to-do parents refused to throw money away at such “utter nonsense.” Leona wrote to her father, asking him to pay for her education, but he also refused.

Deeply resentful, Leona got a job and put herself through school. When she finally graduated with an art degree from the Art Institute, she only had enough money to rent a little studio, where she worked and also began giving art classes. She didn’t have enough money to move out of her grandparents’ house, though, and thus had no choice but to remain there, even though she had grown to seriously dislike them over the years for their “snobbish superficiality. They thought they were something because they had a ‘D’ in front of their name,” she says. “To me, it stood for ‘dumb.’ They thought they were so aristocratic, and it was ridiculous that they only respected people who had more money than them.”

Leona tried her best to ignore her family and their disparaging comments and threw herself into teaching. “It is the greatest fun to teach children,” she says, “because you don’t teach them, they teach you!” After a year of teaching, however, Leona decided to go to New York for a weekend to get away from her mother and grandparents and to also see art museums and galleries. In just a couple of days, she fell in love with New York and returned to Chicago with the intention of packing up and moving there.

She was in the process of going around to different galleries and studios where her friends were to say goodbye, when she happened to meet a new artist, a man by the name of Sherman Abrams. Leona was immediately drawn to Sherman and his work and began following him all around town. She says that she fell in love with him instantly and describes it as “Pow!” Sherman, apparently aware of Leona’s feelings for him, initially tried to avoid her, as he mistakenly thought she was only fifteen. Leona kept finding him, however, and repeatedly invited him to her studio to see her work. Each time he would agree to come but then not show up. Still Leona persevered.

Frustrated by Leona following him, Sherman eventually asked a mutal friend how old she was. The friend said that he thought Leona was in her twenties. Surprised, Sherman finally went to her studio, burst through the door and said “Just how old are you?” When she told him she was twenty-two, he immediately asked her out on a date.

Sherman and Leona eventually married and had two children: Pamela and Rose. Sherman became a very successful commercial artist, and he and Leona were very happy for a time. Sherman’s brothers all loved Leona, apparently, but his mother did not. She resented the fact that Leona wasn’t Jewish, and tried to “make our life miserable,” Leona says. Eventually, the pressure became too much, and the two of them decided to divorce. Leona says that she “grew beyond him.” He was very “juvenile and childish, and his mother wanted him to stay that way.”

After the divorce, Leona packed up Pamela and Rose and moved to New Orleans, where she happily joined the artist community there. She enrolled the girls in a “very good public school in the French Quarter” that emphasized art. Meanwhile, Leona painted, exhibited and taught in various schools. She feels that she was very successful as an artist and as a parent. She is extremely proud of the fact that she devoted so much time to taking her children to see art exhibits, plays, museums and galleries while other women “were at home exchanging housework stories.” She devoted her life to her art and her children and encouraged them to explore any artistic avenue they desired.

As it turned out, upon her graduation from high school, Pamela decided she also wanted to attend the Art Institute. Leona was thrilled with this decision and saw “a lot of promise” in Pamela’s work. Accordingly, she moved them all back to Chicago and contacted Sherman about helping to pay for Pamela’s tuition. She was dismayed when he refused to “give me one cent!” Leona could not believe that Sherman, himself a successful commercial artist, would not encourage his daughter to study art and concluded that perhaps he was jealous of Pamela’s skill. Even now, Leona still seems fixated on this episode in her life, even after so many years have passed. She repeats this story over and over until redirected.

Leona was determined that Pamela should go to the Art Institute, however, and took on two jobs to make the money to pay for it. “I worked night and day,” she says proudly. Similarly, when Rose graduated from high school, she expressed a desire to attend Hunter College in New York to pursue writing. Again, Leona worked two jobs to put Rose through. When both girls were finally finished college, Leona returned to New Orleans to pursue painting and also took up sewing.

Leona remained in New Orleans, living independently, until just about four years ago when she began having difficulty with her health. Pamela suggested that she move back to Chicago. Leona agreed and moved in with Pamela, at Pamela’s invitation, and continued to paint a bit. Not long after the move, however, Leona’s health began to seriously worsen. She had a stroke and also went legally blind. Added to that, she has recently been diagnosed with the beginnings of dementia. She was hospitalized for several weeks after her stroke, and upon her release, the hospital discharge staff recommended nursing home placement.

Leona is very upset about her new living arrangement and has a lot of anger toward Pamela, whom she says “dumped her here.” In turn, Pamela is very sharp toward her mother when she visits, which consist of five- to fifteen-minute intervals. In her more rational moments, Leona says that she understands that it would be impossible to still live with Pamela, but she seems to quickly forget this and grows angry all over again, saying that she paid for half of Pamela’s house and that she should be allowed to live there. At other times Leona is calm and pleasant and attempts to socialize with the other residents. It is hard to participate in activities, though, because of her blindness. She says that she can see light and dark, but no color. “Can you imagine that?” she asks. “What living in a colorless world is like to an artist?” Over all, she seems to be trying to make the best of her situation, but, she says, “I feel empty inside.”

(Originally written: July 1996)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post “So Damned Mediocre!” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 17, 2025

A Girl Like Addie

Liberty Adelaide Appleby was born in Chicago to Alice Myers and Maurice Von Pfersfeld on July 4, 1914. Because she was born on Independence Day, Maurice insisted they name their new daughter Liberty, though Alice had wanted to call her Adelaide. They settled for Liberty Adelaide, but she was always called Addie.

Addie does not remember much about her mother’s family, except that they were of German descent. Her father’s family, she says, immigrated from Alsace-Lorraine. Maurice apparently loved tell the story of how the Von Pfersfeld’s were once barons back in the “old country” and how his grandfather, one Archibald Von Pfersfeld, eloped with a penniless woman and immigrated to America. They made their way to Chicago and to Logan Square in particular, where they had three sons, one of them being Johann, who was Maurice’s father.

Maurice grew up in Logan Square and got a job as a delivery truck driver for the Olsen Rug Company. He met Alice Myers at a church picnic, and after a short courtship, they married. They eventually got their own apartment on Campbell, where they raised their two children: Addie and Marie, who were six years apart.

Addie graduated from elementary school and had begun to attend high school when the stock market crashed, throwing the country into the Great Depression. Maurice, like thousands of others, lost his job. Without Maurice’s paycheck, the family descended into poverty, as they had little savings. They didn’t feel poor, however, Addie says, because everyone else was “in the same boat.”

At some point, the government began giving out food at the local Armory, which the Von Pfersfeld’s had no choice but to accept. Alice, being a proud woman, could not quite bring herself to go down and stand in line, so she sent Addie to go for her. “It was good food,” Addie says, “but it got boring, so we traded with people in the neighborhood.” Addie says that the Depression was a terrible time during which a lot of people suffered, but, on the other hand, she says, it was a time of great camaraderie among neighbors, the likes of which she never witnessed again, even during the war. “People looked out for each other back then.”

Addie quit school and began looking for a job, which turned out to be easier to get than it was for her father. Addie attributes this to her good-looks. “I had a man-stopping body back then,” she says, “and a personality to go it!” Jobs were therefore never hard for her to come by. It was keeping the job that was the problem, as she was forever getting fired for slapping an owner or a manager for “feeling me up” or trying to trap her in a back room. “I wasn’t that kind of girl!” she says. Addie claims to have had so many jobs, often working two or three at a time over the course of her 53-year working career, that she can’t remember them all.

One of her favorites, though, was working at the Chicago World’s Fair, first at an ice cream booth and then as a “Dutch Girl” for a Dutch Rubber Company. Addie says that this was her favorite job because all she had to do is dress up in a Dutch Girl costume and pass out flyers all day. “It was a great job,” Addie says, “because it was easy, and I got to see the whole fair on my lunch break.”

Over the years, Addie had dozens and dozens of waitress jobs. She also worked as a dishwasher, a maid, a floor-scrubber, a counter girl/hair curler demonstrator at Marshall Field, and even as a solderer at a radio factory, which, she says, was terribly boring but paid well. When these more mundane jobs petered out, Addie was obliged to venture into more risqué territory, for which she was easily hired because of her extreme beauty.

Some of these more risqué jobs included working as a “bookie’s girl,” which meant she collected coats and was supposed to serve as many drinks as possible to the “clients.” She also worked as a “26 Girl,” which was a dice game popular in Chicago bars. It was her job to collect money, keep score and encourage men to order drinks, for which she received a percentage of the house’s profits. After that, she took a job as a “taxi dancer” at a local dance hall, where, she says, “I was paid to stand around and look pretty.”

Taxi dancers apparently originated as dance instructors. They were hired by dance halls to instruct men in how to dance. For ten cents, a man could dance with a pretty girl for one dance, thus earning the girls the nickname of “dime-a-dance girls.” Addie says that there really were some shy, quiet boys who actually came in with the intention of learning to dance, but most of the men that came in were there to “feel the girls up.” It was infuriating, Addie says, because the dance hall owners claimed that there was a “no touching” policy, but they not only looked the other way, but actually encouraged men to “have their way.”

This, plus the fact that she would not get off until two or even sometimes four a.m., caused her to finally quit this job, despite the fact that she had a little gang of neighborhood boys who looked after her. These boys knew Addie to be “a good girl,” and out of worry for her would wait at the el stop each night and follow her, at a discreet distance, until she made it safely home.

From taxi dancing, Addie went to being an usherette at a burlesque theater, which made taxi dancing seem like “a kid’s birthday party,” she says. Desperate for money, she saw an ad in the paper when she was nineteen for usherettes at a burlesque house downtown on Monroe. She went to apply and was shocked to find that hundreds of women were lined up around the block, hoping for one of the fourteen available positions.

Addie almost gave up hope then and there, but decided to join the line and take her chances. Once inside, a line of girls were called up on stage and had to show their legs and then lift their skirts to show their buttocks. The men in the seats who were directing these dubious “auditions,” then went down the line, pointed at each girl and saying “left” or “right” to indicate which door they should go through, off stage. The door to the left led to the alley, and the door to the right led to a little side room. Eventually, all the girls in the side room had to line up on stage once more, and this time, the men went down the line, saying “you, you, you, etc.” until they had chosen fourteen girls.

Addie was one of the chosen. She was given a beautiful costume and briefly trained in the art of ushering. The girls were closely chaperoned and a very strict policy of no touching or “hanky-panky” between the customers and the girls was enforced. In fact, there were two male “ushers” who were really there to act as bouncers if any man in the crowd got out of line with the girls. The girls were also required to go to the restroom in pairs for safety’s sake, though, Addie recalls, this policy once backfired for her.

Addie tells the story of how one night, not long after she started, she and a partner went to the restroom as per the policy, but not long after entering the bathroom, another of the usherettes, a girl by the name of Mimi, grabbed her from behind and started kissing her neck. Addie loudly protested and pulled away. Mimi quickly apologized, saying that she had obviously made a mistake. Most of the usherettes, and even the dancers, she told Addie, were actually lesbians. Despite this incident, Mimi eventually became Addie’s best friend and invited her after the shows to her “lesbian parties,” as Addie called them, though none of the girls ever made an advance on Addie again. Mimi became her protector and would often attempt to shield the “innocent” Addie’s eyes from some of the girls “making out” in dark corners.

At some point in time, Addie, who claims to have had “hundreds” of marriage proposals in her lifetime, accepted the hand of one Bill Zielinski and had a child, Hattie, with him. It was a very brief marriage, however, and they divorced when Hattie was only one year old. Addie does not like to talk about Bill or about this time in her life and offers very few details. If asked about it, she will swiftly change the subject.

Apparently, when Hattie was still very little, Addie again married, this time to a man named Arthur Appleby. Arthur was an insurance salesman, and after marrying him, Addie, for the first time in her “adult” life, did not have a job, but instead stayed home to be a housewife and to care for Hattie. Not very long into their marriage, however, Arthur developed Parkinson’s disease and became an invalid, forcing Addie to go back to work. At times she was able to get Hattie, who had inherited her good looks, modeling jobs at Marshall Fields, which helped pay some of the bills.

Addie herself was loathe to go back to any risqué jobs, now that she was a wife and a mother, and tried to find something more respectable. A friend of hers had a job as a private secretary and Besley Wells Tool and Dye and told Addie that there was an opening there as a bookkeeper. Addie knew nothing about bookkeeping, so she went to the local high school, borrowed a book on bookkeeping, and read it overnight. The next day, she went in to Besley Wells, applied for the job and got it. After several years, Besley Wells was bought by Allied Signal, but Addie was able to keep her position in the Loop office. Eventually, however, she was transferred to the office in Beloit, Wisconsin, where she was taught to use a computer. She stayed there for a year before moving back to Chicago.

In all, Addie worked as a bookkeeper for thirteen years before eventually retiring. Arthur died during a surgery the year before she retired. She was sad, of course, she says, but if she were to be honest, it was a relief to not have to care for him anymore.

Despite having to basically raise Hattie herself, work, and take care of an invalid husband, Addie says she was always up for anything. She needed to be busy all the time and always had “a spark” in her eye. Nothing, she says, was too hard for her if she put her mind to it. She had many, many interests and hobbies: ceramics, crocheting, horses, drawing, decorating, home repair, reading, hunting, and fishing, to name a few. She also routinely went to the Art Institute, the Field Museum and the Lincoln Park Zoo and Gardens. If a new interest caught her attention, she would go to the library, find a book on the subject, and learn all about it or teach herself to do whatever it was.

Hattie eventually married and moved to the suburbs, and in the latter years, Addie moved in with her sister, Marie. The two sisters apparently got along very well until Addie had to have bypass surgery in 1990. From there things went downhill, and Addie was eventually diagnosed with COPD and chronic heart failure. The discharge staff advised a nursing home for Addie, especially as she has been given a terminal prognosis and has also entered a hospice program.

Addie is aware of her impending death, but says she is determined to enjoy herself until the very end. She is trying to make the most of the activities at the home but mostly enjoys talking and telling her life story. She is extremely lively and interested in all things around her. Her daughter, Hattie, visits regularly, as does her sister, Marie, both of whom seem to be having a harder time accepting Addie’s situation than she herself is. “What can I say,” Hattie shares, “that my mother hasn’t already said? She is an original. A one-of-a-kind, and I’ll miss her so much when she’s gone.”

(Originally written: December 1995)

(Author’s note: The protagonist of my Henrietta and Inspector Howard series, Henrietta Von Harmon, is based on Liberty Adelaide Appleby! Many of the details of her life as described above can be found in book one of the series, A Girl Like You.)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post A Girl Like Addie appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 10, 2025

Married in His Mind

Arthur Kowalski was born on February 14, 1911 in Chicago to Jacek and Elsie Kowalski, both immigrants from Poland. Neither Jacek or Elsie had had much education in Poland, but upon arriving in Chicago, Jacek quickly found a job working on the railroads. As the years went on, he began to get involved in real estate and would buy businesses, such as corner grocery stores, hardware stores and taverns, operate them for a little while and then sell them for a profit. Elsie, who could neither read nor write, even in Polish, cared for their four children: Sophie, Teresa, Arthur and Nora. When the children got a little older, she also helped Jacek keep the books for his businesses, as, it turned out, she was good with figures despite not being able to read.

According to Arthur, his father had a good reputation in the business world, but he was “rough and tough” and drank heavily. Elsie was always having to be the peacemaker of the family; she wasn’t afraid of Jacek and wouldn’t back down or cower to him. Arthur never got along with his father and says that he would have run away had it not been for his mother.

Eventually, Arthur graduated from high school, and his father surprised him by offering to pay for him to go to college so that he could become a lawyer and help him with his businesses. Arthur refused for two reasons. First, he had no desire to go into law, as he saw this as “a profession for liars.” Secondly, he felt too guilty to take his father’s money when the whole country was going through the Great Depression. His father tried hard to “bully” him into going, but Arthur still refused.

Instead, Arthur got a job, or, rather, a string of jobs, though they were hard to come by. He began going around with a peddler, then found a job as a caddy and then as a printer. None of these he liked very much, so one day, his mother slipped him some money to go downtown to a proper employment agency. The agency accordingly sent him to an office supply company on Madison Avenue for what was supposed to be only a temporary position in the shipping department.

Anxious to prove himself, Arthur worked hard and fast and was soon more productive than anyone in the department, so the company kept him on. He offered to work nights and weekends in addition to his day shift to save the company from having to hire extra people. His boss liked him so much that when his son came home from college in California, he invited Arthur to socialize with him, wanting the two of them to become friends. Arthur declined, however, saying that they were from two different classes and that he didn’t have the money to hang around “a bunch of college boys.”

Right at about this time, when Arthur was twenty-three, he was introduced at a dance to a young woman by the name of Margaret Paszek, who was just twenty years old. Arthur describes her as “a knock-out.” She was only twenty, but the two began dating. Arthur says he fell in love with her right away, but he insisted on dating for five years because he wanted to be sure that she was the one. “I wanted a solid foundation and some money in the bank before I proposed,” Arthur recalls. Margaret was fine with waiting, Arthur claims, as her mother was very strict and probably wouldn’t have allowed her to get married much sooner, anyway.

Finally, though, in 1939, Arthur and Margaret married, but Arthur refused to have a reception, as he did not want to dig into his savings with no guarantee of getting it back in gifts from Margaret’s “mooching relatives.” Despite this unusual beginning, the marriage seemed to go well at first. Arthur continued working feverishly at the office supply company and rose to be not only a bookkeeper, but a manager. He then decided to start taking night classes to get his CPA. He was not very far along, however, when the war broke out, and he immediately joined the army.

Arthur was very proud of the fact that before he left for the army, he had saved up over three thousand dollars, so he knew Margaret would be okay in his absence. As a child, his hobby had been to build radios, so once in the army, he ended up in the radar corp. He was offered officer training, but because it would mean a longer commitment, he declined it. While he was stationed in the U.S., he came home to Margaret every single weekend, no matter what it took. Then, when he was eventually shipped overseas, he wrote her an eight-to-ten page letter every day.

Arthur was eventually shipped to the jungles of New Guinea, about which he has many amazing stories, but was discharged home in 1944, severely underweight and diagnosed with malaria and “jungle rot.” He arrived home, weak and sick, to Margaret and their six-month old daughter, Frances, or Franny. Everything, though, had changed, he says. Desperately ill, Arthur says that all he wanted to do was stay home and rest and get to know Franny. He had no interest in “sex, drinking or going out,” but Margaret was “raring to go.” She began to resent him wanting to stay home all the time, and began instead to go out with her girlfriends once a week. Gradually, it grew to multiple times a week. She started drinking more and even told him that she was having affairs. None of this seemed to phase Arthur, however, who simply lavished all of his love and attention on Franny.

Finally, when Franny was nine years old, Margaret left Arthur and sued for a divorce, which Arthur, a strict Catholic, refused to give her. Instead, he suggested they buy a house in Oak Park and try to start over, but Margaret refused as she saw this as a ploy on his part to get her away from her family who all lived nearby. Margaret’s lawyer then proposed a legal separation, which Arthur also refused. Arthur sought the counsel of the Church Chancery and finally agreed to the divorce, though he saw this as a grave sin, if he could have complete custody of Franny, a condition he expected Margaret to refuse. Shockingly, however, she accepted, and the two went their separate ways. Arthur got an immediate annulment, but remained “married in my mind” for the rest of his life.

From that point on, Arthur began his days at 5 am and ended them at midnight. He devoted himself to caring for Franny. He did all the housecleaning, the cooking, the laundry and the ironing. He curled Franny’s hair in the morning, took her to school, attended her functions, picked her up from school, and had dinner ready every night by 5:30 pm. He was determined, he says, to give Franny a “normal” life and to make up for the lack of a mother figure. He even made it a condition for any new job he began that he would be allowed to leave every day at 4:55 pm, so that he would be on time to pick up Franny.

When he had returned home from the army, Arthur had been offered a chance to go to college on the G.I. bill, but at the time he turned it down, as he felt the stipend was not enough to support the three of them. He instead asked for job training, and they set him up on a two-year program to work in the offices of General Motors. Again, he was extremely industrious, productive and efficient, and he remained there beyond the original agreement, staying for a total of eight and a half years. His whole career was spent working in the offices at car dealerships in some sort of bookkeeping or accounting capacity. He was always in charge of a large staff of office girls, whom he hired, trained or fired, as needed. He feels he was a strict but fair boss and credits himself as being exceptionally honest, precise, stubborn and persistent. He admits to being a workaholic and a perfectionist. He was frequently offered the “top position,” but he never accepted it, though he knew he could do the work, because he felt he would not be fairly compensated since he did not have a college degree. As it is, Arthur is extremely proud of his work and his accounting skills and wishes he could have done more with them.

He is also proud of Franny and his accomplishment in raising her, though he did have some trouble with her during her teen years. During that time, she began covertly seeking out her mother, Margaret, who, Arthur says, “filled her head with lies about me.” Several times Franny ran away, and when she was only seventeen, she got pregnant out of wedlock. Arthur was at first devastated by this, but eventually came around to the new baby, Tommy, whom Franny refused to give up for adoption, despite Arthur’s pleading. In the end, Arthur helped Franny to raise Tommy, who turned out to be “a wild one.” Attempting to tame him, Arthur forced him into the ROTC during high school and often threatened him with sticking him in the navy. When Tommy finally graduated from high school after years of anguish on Arthur’s part, he really did go and join the navy and was stationed in Florida. Many times he has apparently tried to apologize to Arthur for his past behavior and any hurt he might have caused him and Franny, but Arthur has stubbornly refused to accept his apologies.

Besides working and caring for first Franny and then Tommy, Arthur also cared for his mother, Elsie, who was in a nursing home for the last seventeen years of her life. Not only did Arthur visit her every day, but he would insist on getting her up, changing her clothes and her bedding, and taking them home with him to launder. He says he had no time for hobbies, travel, or friendships. His socialization mostly consisted of relationships at work, though he never dated anyone or even entertained that thought, he says, repeating that he remained “married in his mind.”

Just recently, he was admitted to the hospital for a hernia surgery and is therefore staying in a nursing home for a short period of time while he recovers. He lives alone now, Franny having eventually married, and keeps himself busy, he says, with housework and gardening. Arthur is a very pleasant, sweet man who has an amazing memory and will endlessly share stories of his life if asked.

(Originally written: July 1995)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post Married in His Mind appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 3, 2025

They Met at a Candy Shop and Stayed Together for Fifty Years!

Regina Dubala was born on March 24, 1923 in Chicago to Lew Wojciechowski and Stefania Mazur, both Polish immigrants. Regina does not remember what type of work her father did, but she does remember that her grandfather was a lawyer back in Poland. Her mother cared for their four children: Casper, Regina, Albert and Lucy.

Regina Dubala was born on March 24, 1923 in Chicago to Lew Wojciechowski and Stefania Mazur, both Polish immigrants. Regina does not remember what type of work her father did, but she does remember that her grandfather was a lawyer back in Poland. Her mother cared for their four children: Casper, Regina, Albert and Lucy.

Regina went to school until the eighth grade and then got a job in a linen supply company as a stocker. She worked there for five years until she was eighteen years old. At that time, she met a young man by the name of Frank Dubala, three years her senior, at a neighborhood candy shop.

Regina was in the habit of stopping at the candy shop from time to time on her way home from work. Regina reports that she never noticed Frank and his friends, who went there frequently, but Frank, on the other hand, noticed Regina right away. In fact, he says that he fell in love with her at first sight and vowed that she was the girl he was going to marry. He confided this to his friends, who found Frank’s prediction enormously funny, especially considering the fact that Frank and Regina had yet to actually meet. Eventually, however, Frank worked up his courage and asked Regina out and was shocked when she agreed. Regina claims that she had no idea he was interested in her until he asked her out. The two of them hit it off right away, however, and, as Frank predicted, they married within six months.

Not long after they were married, WWII broke out. Frank joined the army and was sent overseas to fight. During the three long years that Frank was gone, Regina lived with her parents and cared for her and Frank’s first baby, Edward, who was born while Frank was away. “It seemed strange,” Regina says, “that one minute we were laughing in a candy shop and the next he’s a soldier and I’m a mother.”

When Frank finally returned home, he and Regina had to get to know each other all over again, and Frank had to get to know his little boy. They eventually got a small apartment on Devon Avenue, and Frank found work as a truck driver. Regina, meanwhile, had another baby, Lois.

Regina and Frank apparently had a very good marriage. They enjoyed going to bars to meet up with Frank’s friends from the service, where they would joke around and talk about their days in the war. They also liked to play cards with friends, garden, and dance. They never traveled at all. Regina said she had no desire to leave home, and Frank, she says, always claimed that he had seen enough of the world during the war. They very much enjoyed their three grandchildren and often took care of them. Sadly, in 1990, Frank passed away of liver cirrhosis. He and Regina had been together for fifty years.

Regina remained on her own for the next four years until she happened to fall, breaking three vertebrae. After her hospitalization, she was unable to go back to the apartment she had shared all those years with Frank and somewhat reluctantly went to live with Lois. Regina eventually adjusted to her new home, however, but then suffered a stroke. She was again hospitalized, and this time, the hospital discharge staff recommended a nursing home for Regina. After much agonizing debate between Lois and Ed, it was decided that their mother would be placed in a home.

Regina says she understands that she can no longer live with Lois, though she wishes she could. Her left side is partially paralyzed, but she is able to communicate, though her speech is slurred, and can participate in many of the home’s activities. She is in relatively good spirits and is trying to make the best of her situation. “What else can I do?” she says. Lois and Ed visit often, which seems to really cheer her. Regina is shy around most of the residents, but she seems to be making friends with her roommate. She will attend various programs if assisted.

(Originally written: May 1996)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post They Met at a Candy Shop and Stayed Together for Fifty Years! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 27, 2025

Her Mother—Age 93— Still Took Care of Her!

Shirley Denenberg was born on November 24, 1923 in Chicago to Aleksandr Krasny and Marie Altman. Aleksandr emigrated from Kiev as a young man and found work in Chicago making cigars. Marie was born in Chicago, though her parents were also Ukranian Jews. She and Aleksndr had three children: Shirley and Susan, who were twins, and Stanley. When they were little, Marie stayed home with the kids, but once they were in school, she found work as a clerk at Woolworths.

Shirley Denenberg was born on November 24, 1923 in Chicago to Aleksandr Krasny and Marie Altman. Aleksandr emigrated from Kiev as a young man and found work in Chicago making cigars. Marie was born in Chicago, though her parents were also Ukranian Jews. She and Aleksndr had three children: Shirley and Susan, who were twins, and Stanley. When they were little, Marie stayed home with the kids, but once they were in school, she found work as a clerk at Woolworths.

Shirley attended high school for a couple of years and then quit to marry her high-school sweetheart, John Denenberg. John was a couple of years older than Shirley and already had a job driving a bakery truck. After they were married, they got an apartment one floor down from her parents’ apartment in a building on Ridge Avenue. Pretty soon, three daughters came along: Mildred, Anna, and Helen. Shirley stayed home with them and says she enjoyed being a housewife and a mother. When the girls were all in high school, though, Shirley got a job working in the office at a public relations firm.

Shirley’s daughter, Anna, says that her mom was the kind of person everyone wanted to know and that she had lots of friends. She loved bowling and all types of board games, Monopoly being her favorite. She and John did a little bit of traveling in their retirement and visited California, Texas, and Nevada before John died in 1988 of Parkinson’s and Liver Cancer. They had been married for 43 years.

Shirley experienced several unexpected deaths in her lifetime. Her father died young of a heart attack at age 58, and her twin sister, Susan, died suddenly at age 52. The death of her sister was particularly hard on her, Anna says. When John died, Shirley again grieved and went through a period of exploring the city, perhaps as a way of dealing with her grief. She would ride the CTA all over the city, Anna says, and would spend all day at museums or walking around neighborhoods.

In the early 1990’s, however, Shirley began to slow down and started having a lot of health issues. She had surgery on her legs at one point, and had a number of falls in which she broke her collarbone and ribs. At that point, she was still living in the apartment building on Ridge where she and John had raised their family. Shirley’s mother, Marie, was likewise still living in an apartment one floor above, and was shockingly in better health at age 93 than Shirley. So it was that when Shirley was recovering from her many falls, Marie came down every day and took care of her and cooked meals for her!

Realizing that this was probably not a good long-term situation, Shirley’s three daughters decided that they needed to take action. Anna took Shirley into her home, and Helen was willing to take Marie, but Marie refused to move to Colorado where Helen lives. In recent months, Shirley now requires regular dialysis treatments and has developed other complications, so the decision was made to move her to a nursing home. Anna says it was a very hard decision, but she is trying to do what’s best for her mother.

Shirley is not happy about her placement and is having a very hard time adjusting. She appears depressed and angry most of the time and lashes out at the staff. She does not like to participate in activities, nor does she seem to interact well with other residents. She has become obsessed with her health and wants to talk or complain about it constantly. When staff attempt to redirect her, she becomes angry and demands to go home. Anna visits as often as she can, but she is also caring for her Downs Syndrome son at home, so she is limited in how much she can help. “In some ways,” she says, “it was easier to have mom at home,” but it just got to be too much. She feels guilty that she can’t do more for her. Both Helen and Mildred live out of state, and Marie still believes Shirley to be living with Anna, though she has been told otherwise.

Meanwhile, Shirley continues to be upset and unhappy. Anna says that it is hard to see her mom this way – so angry and negative, as she was a very happy-go-lucky person when she was younger. Anna suspect’s that John’s death was harder on her then they all thought. “She put a brave face on for a very long time.”

(Originally written: June 1996)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post Her Mother—Age 93— Still Took Care of Her! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 20, 2025

The Egg Man and the Noodle Girl

Sophia Chalupa was born on July 17, 1918 in Chicago to Victor Fiala and Renata Doubek, both of whom were immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Victor worked as a railroad laborer and mechanic in a town near Prague, and after he married Renata Doubek, the two of them decided to immigrate to Chicago in 1908. They settled in the Pilsen neighborhood, and Victor found work in a factory. Renata cared for their three daughters, of whom Sophia was the youngest.

Sophia Chalupa was born on July 17, 1918 in Chicago to Victor Fiala and Renata Doubek, both of whom were immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Victor worked as a railroad laborer and mechanic in a town near Prague, and after he married Renata Doubek, the two of them decided to immigrate to Chicago in 1908. They settled in the Pilsen neighborhood, and Victor found work in a factory. Renata cared for their three daughters, of whom Sophia was the youngest.

Sophia went to school until the sixth grade, when she quit to get a job in a noodle factory. It was her job to weigh the noodles, and she worked there until she met a young farmer by the name of Adam Chalupa.

Adam Chalupa was born on March 15, 1914 in Chicago to Zavis Chalupa and Sara Bobal, who were also Czech immigrants. Zavis had a small farm outside of Brno in Czechoslovakia and also ran a bakery in town. When he married Sara, they, too, decided to try their luck in America and set sail in 1904. They made their way to Chicago, where Zavis bought a small farm on the southwestern edge of the city limits. They had two children, Adam and Amelia.

Adam completed high school and then helped his father to run the farm. Each week, it was his job to drive a load of eggs into the city to sell to various factories, one of them being the Hong Kong Noodle Factory. Over time, he came to know a pretty young woman who worked there by the name of Sophia Fiala. At first he was attracted to how pleasant and kind she always was, but he was further delighted to discover that she was of Bohemian descent, just as was he.

Adam eventually worked up the courage to ask Sophia out on a date and was thrilled when she said yes. They dated for about a year before Adam proposed. The two of them were married in Sophia’s parish of St. Procopius in 1941. After the wedding, Sophia went to live with Adam and his parents until they saved enough money to buy their own farm in Wilmington, Il., which was southwest of the city and not too far from Adam’s parents. Adam farmed and also did custom welding work on the side for extra money, while Sophia cared for their three children: Peter, Frank and Bessie. They were both active in their church, but they mostly lived a quiet life.

In 1969, Adam and Sophia decided to sell the farm and move to Berwyn, Il. where Adam continued to do custom welding on a part-time basis. Sophia began volunteering at St. Odilo’s, and Adam got involved in the Bohemian Concertina Association. Playing the accordion had always been a hobby of his, so now that he had the time, he decided to form a band called the Polkateers.

The Polkateers played together for over twenty years, performing at nursing homes, senior centers, community centers, as well as at festivals and libraries. Eventually, however, several members died and replacements proved to be hard to find, so the Polkateers eventually disbanded. By then, all three of Adam and Sophia’s children were married with families of their own. Peter had married and moved to Cincinnati, and both Frank and Bessie had moved to Batavia, Il.

Sophia, never having learned to drive, longed to be closer to their grandchildren, so Adam sold the house in Berwyn in 1981 and they moved to Batavia to be closer to Frank and Bessie’s families. Sophia became very involved in their grandchildren’s lives and delighted in babysitting for them. Adam and Bessie took a couple of trips over the years—one to Cincinnati to see Peter and his family and one to New York, but otherwise, they were happy gardening and playing cards.

In the early part of 1993, Sophia began having a lot of health problems and was eventually diagnosed with heart problems, diabetes and dementia. Adam tried his best to care for her at home, but found it hard. Finally, with the help of their daughter, Bessie, Sophia was admitted to Walnut Grove nursing home in Batavia. Only a few months later, Adam was diagnosed with colon cancer, among other things, and had to have various surgeries. Upon discharge from the hospital, he was also admitted to Walnut Grove. Adam reports that the staff at Walnut Grove were nice, but he hated the food and longed for the Bohemian dishes that Sophia had always made. It finally occurred to him to move to the Bohemian Home in the city where he and the Polkateers had performed—and where he had always been served delicious, complimentary lunches—for many years.

Bessie and Frank were not too enthusiastic about this plan, as it would make visiting harder for them because of the drive, but Adam was resolute. Thus, both he and Sophia were both eventually transferred to the Bohemian Home, where Adam is acclimating nicely. Sophia, however, who never really got used to Walnut Grove, is having a more difficult time. She is disoriented and combative and spends the day pacing the hallways, asking to go home. She does not seem to remember their time at Walnut Grove and says she feels like a prisoner. She directs her anger mostly at Adam, whom she feels is somehow responsible for their predicament. Adam, meanwhile, though he is concerned for Sophia, is enjoying his reunion with many of the Czech people he came to know over the years, including Otto, a blind resident at the Home who used to work there as a janitor in his younger days and who had befriended Adam many years before.

(Originally written: October 1993)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post The Egg Man and the Noodle Girl appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

November 28, 2024

“One Christmas Left”

Angela Esposito was born on September 29, 1918 in Chicago. Her father, Leo Esposito, came to America as a young man from Florence, Italy. He made his way to Chicago and found work as a stone mason. After working as such for several years, he saved enough to open an ice cream parlor and made all the ice cream and candy himself. He met another Italian immigrant, Benigna Ricci, and they soon married in 1917.

Angela Esposito was born on September 29, 1918 in Chicago. Her father, Leo Esposito, came to America as a young man from Florence, Italy. He made his way to Chicago and found work as a stone mason. After working as such for several years, he saved enough to open an ice cream parlor and made all the ice cream and candy himself. He met another Italian immigrant, Benigna Ricci, and they soon married in 1917.

One year later, their first child, Angela, was born. The little family lived in Lakeview at Diversey and Wilbur, and it wasn’t until seven years later before another baby was born, Claudia. Angela and Claudia went to school in Lakeview and even attended high school.

Upon graduation, Angela got a job downtown as a secretary. Angela enjoyed her position, but after a few years, a friend encouraged her to look for work in the legal departments of companies because the salaries were higher. Angela, always shy and hesitant, deliberated this move for a long time, but then decided to take her friend’s advice. She switched to being a legal secretary and in that capacity worked for many years as a temp. This suited her because she made a lot more money, though she didn’t get benefits. Occasionally, a company she was temping for would offer a permanent position, and if she liked it, she took it.

Though she was “on the quiet side,” Angela was very social. She made some good friends at her various jobs and loved getting together with “the girls” after work. Their favorite activity was to go to dinner at the Italian Village and then head over to the Schubert or the Blackstone to see plays. Angela loved the theater and music of any kind. She also loved reading (mystery was her favorite!) and watching Westerns on TV. She also loved to play scrabble.

Though she had many friends and went out a lot, Angela never seemed to find a man she loved enough to marry, she says. There was one boy she met at school, but he was Polish. She didn’t think her parents would approve of him, so she never allowed a real relationship to develop. Angela says she went on a number of dates over the years, but she always had more fun with her girlfriends. Her parents were always offering to set her up with a nice Italian boy, but she always just laughed and said no.

As the years went on, however, her mother, Benigna, grew more and more impatient for a grandchild, so when Angela’s sister, Claudia, announced that she was getting married at age 23, Benigna was overjoyed. It was then that she confessed to Angela, simultaneously swearing her to secrecy, that she had recently been diagnosed with cancer. She kept it a secret from everyone, except Angela, and Leo, of course, until after the wedding when she had seen Claudia and her new husband off on their honeymoon to New Orleans. Later that same day, Leo drove her to the hospital for her first surgery.

Angela, still living at home, became her mother’s primary caregiver. Angela and her father spent the next year “watching Benigna waste away,” until she finally died at age 52 on Thanksgiving Day, 1949. Angela says that she has never since been able to enjoy Thanksgiving. Four years after her mother’s death, Leo, too, died from complications with diabetes. Claudia and her new husband had since moved to New Jersey, and Angela found that she did not like living in the family apartment alone. Accordingly, she decided to move into a hotel apartment nearby with a girlfriend from work.

Angela was happy there and stayed until the early 1960’s when she decided to get her own place and found a studio apartment in Rogers Park for $92 a month. She stayed there for fifteen years, but as the neighborhood grew more and more unsafe, she put her name on a waiting list for an apartment at North Park Village and moved to the northwest side for the interim. Finally, in 1990, she got a call saying that an apartment had opened up, and she moved in right away.

Angela enjoyed meeting her new neighbors and was able to live very independently for several years until she began to slow down in the summer of 1995 when she became very lethargic and lost a lot of weight. When she finally went to the doctor, she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. She was hospitalized for about four weeks and then made the move to a nursing home with the help of the hospital discharge staff.

Fortunately, Angela has a nephew, Tom, living in Chicago, and he and his family have become very supportive of Angela. Claudia has long since passed away, so Tom is all she has. Tom and family visit often and are trying very hard to make Angela’s remaining time as pleasant as possible. Angela, for her part, says she has never handled stress well, but realizes that “crying and going into hysterics” in light of her prognosis, “isn’t going to help anything.” At times, she is very sad, especially as she realizes she only has “one Christmas left,” but she is trying hard to be positive. She is a very sweet, down-to-earth woman who always seems to have a kind word for those who stop to talk to her. The staff encourage her to mingle with the other residents, but she mostly prefers to stay in her own room.

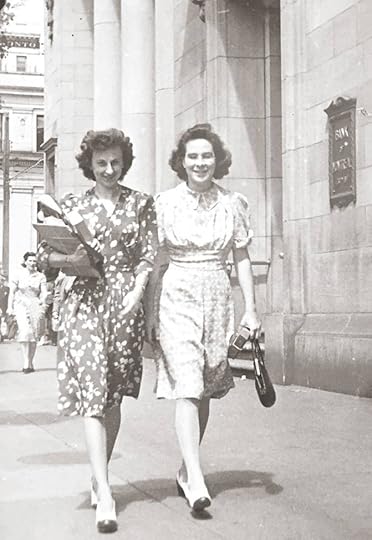

(Originally written December 1995)/(Photo: Angela Esposito, left)

If you enjoyed this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery novels, THE HENRIETTA AND INSPECTOR HOWARD series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Or you might try her new stand-alone historical women’s fiction, THE FALLEN WOMAN’S DAUGHTER, also partially set in Chicago:

Or a brand-new series, THE MERRIWEATHER SERIES—Small-town historical fiction based in 1930s Wisconsin!

The post “One Christmas Left” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.