Michelle Cox's Blog, page 7

April 27, 2023

She Made Her Way to America Alone, Age 14

Mirna Claesson was born on November 29, 1900 in Velika Gorica, Croatia, near Zagreb. Her parents were Dejan and Nada Juric. Mirna was the oldest of three children and went to school as far as the sixth grade. At that time, when she was about eleven, her mother died. Following her death, her father, Dejan, decided that he would try to start over in America. He left his two youngest children, Emil and Blazenka, in the care of a relative, and took Mirna, age 12 at this point, with him on the long journey. His plan was to send for the younger two once he was established in his new country.

Mirna Claesson was born on November 29, 1900 in Velika Gorica, Croatia, near Zagreb. Her parents were Dejan and Nada Juric. Mirna was the oldest of three children and went to school as far as the sixth grade. At that time, when she was about eleven, her mother died. Following her death, her father, Dejan, decided that he would try to start over in America. He left his two youngest children, Emil and Blazenka, in the care of a relative, and took Mirna, age 12 at this point, with him on the long journey. His plan was to send for the younger two once he was established in his new country.

Unfortunately, however, he and Mirna only got as far as the Hungarian border. The officials there would not let Mirna cross as she had no paperwork, and Dejan could not prove that she was really his child. Desperate, the two agreed that Dejan would cross the border and continue on to America and that Mirna would make the return journey back to Croatia on her own.

She was able to make it, and once back at home, she began the long process of trying to get her papers in order. In all, it took over two years to not only get her papers, but to save enough money to start the journey all over. When she was fourteen, she set off on the journey again, this time hoping that everything was in order. She again left her brother and sister behind and managed to travel cross-country, alone, and eventually boarded a ship for America.

On the sea voyage, Mirna became desperately ill. When she finally arrived at Ellis Island, she was nearly sent back because of a terrible eye infection. By some chance, she was instead quarantined. Eventually, her condition did improve, and she was able to leave. She traveled by train to Chicago, where she was finally reunited with her father.

Dejan had found work in various factories around the city, and to Mirna’s surprise, he had remarried. Mirna quickly found work as a seamstress, and she and her father and his new wife, Sophia, were able to send for Emil and Blazenka after about a year. The family was not reunited for long, however, before Dejan died in 1918 of the flu epidemic.

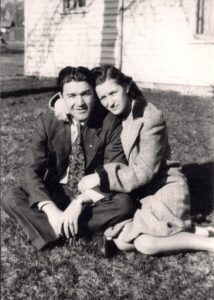

That same year, Mirna met a man by the name of Paul Jagoda at a birthday party of a mutual friend. They began dating and, after a very short courtship, were married. Mirna was 19 and Paul was 30. By 1920, Mirna gave birth to their first child, Paskal.

In 1924, the young couple decided to move to Medon, Ohio, where they rented a farm. It was in Medon that they met Anna and Anders Claesson, who lived on the neighboring farm and who became their life-long friends. When Mirna gave birth to her second child, Wilma, it was Anna Claesson who acted as midwife/nurse for the rural doctor when no one else could be found, even though she herself had no children.

After Wilma’s birth, Mirna’s health declined and she began to have problems with her kidneys. Much as they hated to leave their farm and their good friends, Paul and Mirna decided to return to Chicago in hopes that Mirna would get better medical care. They found an apartment in Rogers Park, and Paul got a job as a janitor for a large apartment complex.

Eventually, Mirna’s health improved, so in 1933, they decided to go back to Medon, this time with enough money saved to put a down payment on a farm of their own. They worked the farm for thirteen years until Paul died very suddenly one day of a heart attack at age 56. Mirna stayed on at the farm with the help of the Claessons, who were still their very good friends.

Two years after Paul’s death, however, Anna Claesson died of cancer. Now it was Mirna’s turn to comfort Anders, and as time went on, the two old friends fell in love. It was a very smooth transition for Paskal and Wilma to accept their new step-father, as they had practically known the Claessons all their life. Anna and Anders never had children and had instead spent years spoiling the Jagoda children, thus Anders felt it easy to slip into the role of their father.

This was 1946, and after they were married, Mirna and Anders decided to leave all of their memories behind in Medon and went to Chicago where they bought a house in Berwyn. Anders found a job as a foreman and was later the co-owner of Ettinger Manufacturing Company. He and Mirna had many happy years together until he, too, died of a heart attack at age 84.

Mirna lived alone after that and continued to bake and to garden, which had always been her biggest hobby. In fact, back in Medon, she had had a reputation in the area for having the most beautiful vegetable and flower gardens. So visually stunning were they that often people traveling through town would stop and photograph them.

On Mirna’s 85th birthday, Paskal and Wilma gave her a big birthday party and invited lots of friends and family. Mirna enjoyed every minute of it and was, up to that point, perfectly alert and independent. Soon after the party, however, Wilma began to notice that her mother seemed to be “slipping” mentally and was becoming more and more agitated.

Things seemed to worsen quickly, and Paskal and Wilma consulted about how to handle the situation. They finally decided to hire a private nurse/housekeeper to live with Mirna, but it was not a successful arrangement. The two personalities clashed, and Mirna’s appetite declined severely. Twice she managed to elude the housekeeper and was found wandering in the neighborhood, lost and disoriented. Wilma and Paskal, both retired themselves, knew something else had to be done, but neither could handle bringing Mirna to live with them. Instead, they reluctantly decided to admit her to a nursing home.

Between them they decided not to tell Mirna the whole truth behind the plan, as Mirna had sworn all her life that she would rather die than go into a home. Needless to say, Mirna was very angry and agitated, as well as confused, upon her admission. She has since calmed down a bit, however, now that she has met some of the other eastern European residents with whom she can speak. Likewise, the activities department has recruited her help in the garden, and she seems to enjoy all of the ethnic food provided by the home, which pleasantly includes a glass of beer or wine with dinner. Mirna is a very lovely woman, eager to please, though at times confused. She seems to believe that her stay here is temporary until Paskal and Wilma “fix up a room” for her in Wilma’s house, hence her distress has lightened considerably and her adjustment is improving.

(Originally written: December 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Made Her Way to America Alone, Age 14 appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 20, 2023

From the Luftwaffe to Chicago Tool and Die

Deiderich Muller was born on July 27, 1921 in Dortmund, Germany to Adolf and Elisabeth Muller. Elisabeth had been married before to a man named Karl Achterberg and had one child with him, Ada, before he was killed in the First World War. Elisabeth was apparently a very strong, dominant woman and married again, this time to Adolf Muller, a factory worker. They also only had one child, Deiderich. Not much is known about Deiderich’s early life except that he received very little schooling and that at a very young age, he began working with his father in the factory.

Deiderich Muller was born on July 27, 1921 in Dortmund, Germany to Adolf and Elisabeth Muller. Elisabeth had been married before to a man named Karl Achterberg and had one child with him, Ada, before he was killed in the First World War. Elisabeth was apparently a very strong, dominant woman and married again, this time to Adolf Muller, a factory worker. They also only had one child, Deiderich. Not much is known about Deiderich’s early life except that he received very little schooling and that at a very young age, he began working with his father in the factory.

When World War II broke out, however, Deiderich was forced into the German air force and served as a radio dispatcher in the air. It is a part of his life that he has never talked about, even to those closest to him. He was shot down at some point and captured and was taken to a prisoner-of-war camp in Holland. This is all he will say about that time in his life.

When the war was finally over, Deiderich decided to come to the United States to start a new life. He came to live with his aunt and two cousins in Chicago and got a job as a tool and die maker. He was apparently a very hard worker and also very shy. All of the friends he made here were also German, as he could speak to them easily and could avoid having to become fluent in English that way. He joined a German club and spent a lot of his free time playing soccer with his friends.

When he was about thirty years old, however, he began toying with the idea of going back to Germany. He changed his mind, though, when he met a woman by the name of Gertruda Hoffman. Gertruda, who was several years older than Deiderich, was a Polish/German mix and could speak German, much to Deiderich’s delight. Deiderich was apparently very attracted to her and was disappointed to learn that she was already married. Though she was separated from her husband, Deiderich tried to keep away from her, but they kept running into each other and soon began dating.

Eventually, Gertruda divorced her husband and married Deiderich. It was not a happy marriage, however, though it lasted thirty-one years. Gertruda was apparently a very cold, unhappy woman who often made fun of Deiderich’s broken English and forced him to go to night school to try to improve his language skills. Together they had one child, Anna. Gertruda did not want a child at all, but she finally gave in to Deiderich’s pleading for one. After Anna, though, she refused to have another one.

The marriage ended abruptly in 1985, when Deiderich came home from work and found a note from Gertruda saying that she had met someone else and was leaving him. Alone again, Deiderich went back to spending all of his time at his German club and went to many dances, where he met his new wife, Joan Mayer, who was of German and Irish descent. Joan and Deiderich married in 1991 and seemed very well-suited. They enjoyed a lot of the same things, Joan reports, and had common friends and interests, especially dancing.

After only two years together, however, Deiderich had a small stroke, after which Joan noticed that his behavior began to change. The most obvious difference to her was that he began to mismatch his clothes. Previously, Joan says, he had always appeared so dapper—neat and trim and usually dressed in a suit. Unfortunately, despite Joan’s efforts to help him, Deiderich seemed to get worse, and after a string of doctor visits, was eventually diagnosed with Alzheimer’s.

Against everyone’s advice, Joan sold their house, and the two of them moved into a condo, which further disoriented Deiderich. Desperate to provide for him, Joan hired nurses to help with his care, which seemed to work for a time. Recently, however, he has begun to be combative, not just with the nurses, but with Joan, too, and the decision was reluctantly made for him to go into a nursing home.

At this point in Deiderich’s life, his daughter, Anna, suddenly decided to get involved. She and Joan have apparently never gotten along, and now that Joan had decided to put Deiderich in a nursing home, Anna insisted that it be in a facility near her home in Addison, Il. Joan protested, saying that not only would it be very difficult for her to visit him out in Addison, but it would be likewise difficult for Deiderich’s best friend and cousin, William, to visit, too. Joan and Anna continued to argue so much that eventually a state guardian was appointed. After looking over the case, the guardian ruled in favor of placing Deiderich in the city near Joan and William.

Joan, though very pleased with the state guardian’s decision and with the nursing home in general, remains distressed about Deiderich’s placement. She visits constantly and repeatedly talks about feeling cheated out of the life she and Deiderich had planned. She is hoping for a cure so that he can come back home and they can take up their plans just where they left off. She does not accept that Deiderich’s condition and placement are permanent.

Deiderich, for his part, is relatively calm and non-combative. He does not interact with other residents, nor does he participate in many activities. While he does not seem agitated, he is confused and seems unhappy. When Joan is not visiting, he can be frequently found sitting alone in a chair, often crying. It is difficult for the staff to bring either of them any sort of comfort.

(Originally written: October 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post From the Luftwaffe to Chicago Tool and Die appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 13, 2023

Orphaned at Age Eight

Maria Kumiega was born on June 7, 1913 in Poland to Albert and Milena Gajos. Milena’s maiden name was also Gajos, though Maria says her parents weren’t related. Albert owned a small farm, and Milena cared for Maria, who was just a baby when World War I broke out. Albert was soon rounded up to serve in the Russian navy, and tragically, he never returned. Milena eventually remarried, but while giving birth to her first child with her new husband, both she and the baby died. Maria’s new stepfather could not even stand to look at Maria after that and abandoned her, making Maria essentially an orphan at age eight.

Maria Kumiega was born on June 7, 1913 in Poland to Albert and Milena Gajos. Milena’s maiden name was also Gajos, though Maria says her parents weren’t related. Albert owned a small farm, and Milena cared for Maria, who was just a baby when World War I broke out. Albert was soon rounded up to serve in the Russian navy, and tragically, he never returned. Milena eventually remarried, but while giving birth to her first child with her new husband, both she and the baby died. Maria’s new stepfather could not even stand to look at Maria after that and abandoned her, making Maria essentially an orphan at age eight.

Eventually, it was arranged for Maria to go live with an uncle in a distant village. Her life with her uncle wasn’t terrible, she says, though she was not treated like the other children in the family and was made to work very hard. She received only a couple of years of schooling, but she was eager to learn and taught herself to read and write, despite the long hours she put in around the house and farm.

It is not surprising, then, that she married very young—at sixteen—to Daniel Kumiega, a boy she had grown up with in her uncle’s village. Daniel, a few years older than her, saw how difficult it was for Maria in her uncle’s home and was subsequently very kind to her. Often, on Sundays, he would bring her a sweet wrapped in his handkerchief. Maria appreciated his visits and his gifts, though they made her life more difficult, as she had to hide them from the family. Maria grew to love Daniel, even from a young age, so when he asked her to marry him, she didn’t have to think about it at all and immediately said yes. She had hoped to use the land owned by her parents as a dowry, but it had long-since been been confiscated. Thus, Maria came to Daniel with nothing, but he claimed not to mind. He quickly found work on a nearby farm, and Maria soon had a baby, Marta, to care for.

Maria does not like to talk about the Second World War and does not say how the little family survived it. She merely comments that when it was finally over, there was little opportunity to make a living. They did not want to stay in Communist Poland, so in 1948, they escaped to France. Daniel found work on farms there, and they remained for thirteen years, during which time another child, Bosko, was born.

When the French economy took a downturn, however, Daniel could no longer find any work. He was forced to take a job in the mines, though the conditions were grueling. Eventually, Daniel could no longer take the back-breaking work, and, likewise, he found it especially hard to be underground all day when he had spent his life working outdoors in the fields. Desperate, they decided to immigrate to America and applied to the Catholic League for help. Finally, around 1961, they made it to Chicago. Their son, Bosko, came with them, but Marta remained behind as she was already married. Daniel found work as an unskilled laborer in factories, and though it wasn’t outdoor work, he was grateful that he was no longer in the mines. Eventually, Marta and her husband and children made their way over, too.

After saving for a long time, Maria and Daniel were able to buy a small house in Humboldt Park, which was Maria’s pride and joy. Unfortunately, however, Daniel died in the early 1970’s, making it very hard for Maria to hold onto the house with only a job as a cleaner. Neither Bosko nor Marta were not able to help her financially, as they were both struggling themselves to raise families and to pay a mortgage. Finally, then, as the neighborhood grew worse and worse and Maria became more and more afraid, she sold the house for much less than it was worth and bought another one closer to Bosko.

Maria was happy in her new house and remained an active member of St. Hyacinth’s parish. She also spent much of her time gardening, her favorite thing to grow being roses. She has remained independent until very recently when she was diagnosed, at age 83, with renal failure. She requires more help now and has difficulty getting around. For several months, both Marta and Bosko have tried to stop over to help her or to bring groceries, but the stress has begun to wear on them, especially as they are not on speaking terms with each other. Apparently, they separately approached Maria to suggest to her that she go into a nursing home, the thought of which was initially very disturbing to Maria. Maria begged to instead live with one of them, but Bosko explained that it would be difficult to care for her since no one would be home with her all day, as everyone in both families either worked or went to school. No one would be there, Bosko pointed out, if she fell or needed help. Eventually, then, after several months of thinking about it, Maria agreed to go to a nursing home.

Maria has made a relatively smooth transition to the facility, though she likes to remain in her room alone unless the staff urges her out to socialize. Once outside of her room, she enjoys speaking with other Polish residents and attending Mass and bingo. More than anything, however, she looks forward to visits from Marta and Bosko, though they are careful never to visit at the same time, as they claim to hate each other. Maria, thankfully, seems not to be aware of this. At first, the staff did not even realize that Maria had a daughter, as, during the admission process, Bosco, who arranged it all, neglected to even mention that he had a sister. The staff were very surprised, then, when Marta appeared one day, claiming to be Maria’s daughter. Bosko then admitted that he did have a sister, but stated, “she is too stupid” to be of much help. Maria meanwhile seems unaware of any family disunity and is simply grateful if one of them turns up. If the weather is very warm, she can sometimes be found sitting in the gardens on her own. “I’ve had a hard life,” she says, “but it hasn’t been all bad.”

(Originally written: April 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Orphaned at Age Eight appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 6, 2023

She Was Jane Russell’s Manicurist

Hazel Reuter was born on May 17, 1920 in Chicago to Douglas Wilson and Eileen Brady, who were of Scottish and Irish descent, respectively. Douglas worked in the produce business, and Eileen cared for their five children: Vernon, Victor, Hazel, Gerald and Jane. Sadly, however, both Vernon and Victor died as toddlers in the flu epidemic. Then, when Hazel was just ten years old, Eileen died at age 36 of stomach cancer.

Hazel Reuter was born on May 17, 1920 in Chicago to Douglas Wilson and Eileen Brady, who were of Scottish and Irish descent, respectively. Douglas worked in the produce business, and Eileen cared for their five children: Vernon, Victor, Hazel, Gerald and Jane. Sadly, however, both Vernon and Victor died as toddlers in the flu epidemic. Then, when Hazel was just ten years old, Eileen died at age 36 of stomach cancer.

According to Hazel, Eileen had been a very beautiful woman, and her father had adored her. When she died, he fell apart and could not take care of the three children that remained. Eventually, he arranged for relatives to take them in. Hazel went to Eileen’s sister and Gerald and Jane went to Eileen’s mother. Tragically, though, Gerald died just three years later, in 1933, of a brain tumor, which plunged the family into grief all over again.

Finally, at some point, Douglas pulled himself together enough to get a little apartment on Hudson Avenue in Lincoln Park in an attempt to make a home for Hazel and Jane, his only surviving children. Hazel says it was very nice for a time, just the three of them, until Douglas remarried. After that, Hazel says, the atmosphere in the home became tense and abusive. The situation with her new stepmother grew so bad that one night, in desperation, Hazel, aged 17, packed a grocery bag full of clothes and left the house. She went to her grandmother’s home at Ravenswood and Irving Park Road and asked if she could stay with her. Her grandmother of course took her in, and Hazel quickly got a job at a toy factory – one of the many factories in the area.

Jane soon followed Hazel to live with their grandmother and got a job as a housemaid for a wealthy family living on Lake Shore Drive. Jane married young at age nineteen, and over the years, she and Hazel lost contact, though Hazel does not say why.

In 1945, when Hazel was twenty-five, she met a young soldier, Benjamin Reuter, who was home on leave. They met at the Aragon Ballroom, and Hazel agreed to write to him while he was away. As soon as Benjamin was discharged from the army, the two were married.

It was a difficult marriage, however, in that Benjamin was of Russian Jewish descent, and his family ostracized them because Hazel was Christian. Only Benjamin’s mother would occasionally speak to Hazel. Likewise, Hazel had very little contact with her own family, so they were very much on their own. Benjamin found work as a cab driver, and Hazel cared for their baby, Marian, in a tiny, one-room apartment. Eventually, their financial situation improved with Hazel working part-time in various factories, and they moved to a bigger apartment.

When Marian was nine, Hazel and Benjamin had another baby, Charlie, followed quickly by Pearl. At this point, the marriage seemed to break down, with Hazel and Benjamin eventually separating. Both Charlie and Pearl, Hazel says, have few memories of their father. Hazel began then to work as a manicurist and eventually found a job at an exclusive salon that catered to the “rich and famous.” Hazel is very proud of the fact that she gave Jane Russell her manicures on a regular basis. After many years of this, however, the stress apparently got to her and she quit.

It was at this time that Benjamin, estranged from them all these years, was diagnosed with leukemia. In April of 1970, he came back home to Hazel to die. Remarkably, Hazel diligently nursed him for two months until he passed away in June of that same year. Charlie and Pearl were teenagers at the time. Marian, on the other hand, had already moved out by then and was married to “a man who controls her,” according to Hazel. Eventually, Pearl married, too, and moved to Missouri. Only Charlie remained with his mother.

In 1974, Hazel had two heart attacks and spent thirty days in the hospital. She eventually went back home and recovered and spent much of her time trying to help Charlie, who appears to be somewhat unstable, both mentally and emotionally, with his many issues. Besides taking care of Charlie, Hazel’s favorite pastimes were cooking and walking to thrift stores.

Around 1985, Hazel’s life took a different turn. She happened to hear about and attended a prayer meeting led by an “evangelical preacher” who went only by the name of “Farlo.” Hazel became enraptured with Farlo’s preaching and completely immersed herself in his particular brand of religion, which she refers to as “The Message.” Hazel now believes that God talks to her and has given her various gifts, such as speaking in tongues, a complete knowledge and understanding of the bible, the ability to prophesy and read minds, as well as the power to heal others by praying over them or touching them.

Recently, Hazel has been experiencing blood-pressure problems and was hospitalized for five days. Her doctors were not convinced of her ability to go home, even with, or perhaps because of, Charlie being there, so she agreed to go to a nursing home. Hazel believes, however, that she will heal herself in exactly one month’s time and then be released. Charlie, meanwhile, seems overwhelmed by his mother’s placement here. He visits frequently, but rather than offer her encouragement and support, it is she who ministers to him. He sits with her for hours, during which time she tries her best to comfort him.

Hazel is not acclimating well to the home, as she views her stay here as temporary. At times, she is very accepting and pleasant with the staff, and at other times she can be verbally abusive. She seems content to read her bible and pray and to sit quietly with Charlie watching TV. Though very alert and able to communicate, she does not seem concerned with her medical prognosis nor her plan of care.

(Originally written: November 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Was Jane Russell’s Manicurist appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 30, 2023

She Lived to be 100!

Tereza Hlavacek was born on August 15, 1895 in what was then called Bohemia, the part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that later became Czechoslovakia. Her parents were Dobroslav and Marie Cipris, about which little is known. Tereza was one of four children and attended grammar school before she quit to start earning money, which the family desperately needed. She didn’t have much luck, however, so when she was just fifteen or sixteen, she decided to follow her older sister to America, hoping to get a job there. She made the journey alone and traveled to Chicago, where her sister was living in a boarding house. An uncle, Joseph Krall, also lived nearby, and he gave Tereza a job working in his tailor shop.

Tereza Hlavacek was born on August 15, 1895 in what was then called Bohemia, the part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that later became Czechoslovakia. Her parents were Dobroslav and Marie Cipris, about which little is known. Tereza was one of four children and attended grammar school before she quit to start earning money, which the family desperately needed. She didn’t have much luck, however, so when she was just fifteen or sixteen, she decided to follow her older sister to America, hoping to get a job there. She made the journey alone and traveled to Chicago, where her sister was living in a boarding house. An uncle, Joseph Krall, also lived nearby, and he gave Tereza a job working in his tailor shop.

Not long after she arrived, Tereza was introduced to Bernard Hlavacek, who did odd jobs for her uncle and also worked as a delivery man. Bernard, a quiet, shy boy, supposedly fell in love with Tereza right away, impressed by her ability to work hard and the way she always comported herself. Bernard was nervous to ask her out, however, fearing what her uncle would say, and instead spent a year worshipping her from across the shop. Finally, Tereza’s uncle pulled him aside one night and asked what he was waiting for. Bernard, stunned with relief and overcome with joyful hope, asked Tereza the very next day to walk with him in Humboldt Park, to which she said yes. They began dating in earnest, then, and married shortly after.

Once married, Tereza stayed home to be a housewife, and Bernard continued working with her uncle, having been elevated now to a full tailor. Eventually the young couple was able to buy a small house with a big yard, which Tereza converted into a huge garden and which she diligently worked in every day. They had two sons, Joseph and Simon, both of whom Tereza was very attached to.

Tereza toiled endlessly for her little family and was reportedly a very strong, independent woman. She was apparently quite stubborn and wanted her own way in most things, but she was also most appreciative of any little thing anyone ever did for her or gave to her. Her daughters-in-law report that Tereza was also a little bit vain, her appearance always being very important to her. Though they had little money, Tereza made it a point to always be nicely dressed. There is a family story that once when one of Tereza’s friends was about to leave on a trip to Europe, Tereza was so disgusted by her friend’s old, tattered hat that she whipped off her own hat and gave it to her, saying “Here! Take mine!” Even in her nineties, Tereza always donned a sweater because she was unhappy with how her arms looked.

Though Tereza has always been a strong woman in many ways, she has also been a very nervous person, especially as the years have gone on. Apparently, when Joseph and Simon both went into the army, Tereza became so fraught with worry that her ears started “draining,” and she went deaf in one ear. The worst blow to her nerves, however, was when Bernard passed away at age 57. He had a stroke while working in the yard and was taken to Cook County Hospital. Tereza visited him faithfully each day, but on the third day, when she arrived to see him, she was shocked to find his bed empty. When she asked where her husband was, she was told nonchalantly that he had died in the night. From that point on, Tereza says, she developed “the shakes.”

After Bernard’s death, Tereza threw herself into community and church activities. She still gardened and traveled daily from Cicero to the Bohemian National Cemetery in Chicago to lay flowers on Bernard’s grave, a ritual she kept up for six years. In addition, she began cooking for the Bohemian club she belonged to and also started crocheting again. She had always enjoyed crocheting as a hobby, but after Bernard’s death, it became almost a frenzied obsession. Her daughter-in-law, Rita, says that she must have produced thousands of baby booties over the years. She also found solace in traveling and went to Oregon, Florida, Hawaii, and to Europe twice. Sometimes she used a travel planner, but sometimes she made all her own arrangements.

Tereza continued to live independently until 1982, when she had to have a hip replacement. It was then that her son, Joseph, persuaded her to move in with him and Rita. This seemed appropriate to Tereza, Joseph being the oldest, though her favorite was Simon, whom she always referred to as “my baby.” Tereza’s hip mended well, though she continued to have pain on and off through the years. It didn’t stop her from being active, however, and she continued to garden until she was 94.

Unfortunately, Joseph passed away from cancer in 1985, just three years after Tereza had moved in. It was a terrible blow, again, for Tereza and for Rita, but they helped each other get through it. After her son’s death, Tereza began to slow down, and she became much weaker than she had been. She had to rely on Rita for things she had always been able to do herself, such as bathing and dressing. Simon and his wife, Norma, not wanting all the burden of care to be on Rita, started coming over regularly to help, but it was difficult for them all. Rita developed severe arthritis and became increasingly worried that something would happen to Tereza, such as a fall, and that she wouldn’t be able to help her. Finally the stress became so great that the four of them sat down and discussed the possibility of Tereza going into a nursing home. Tereza was not thrilled by the suggestion, but she was not unreasonable and seemed to understand that she did not have a lot of choices. They all went and toured several places, and Tereza eventually chose The Bohemian Home for the Aged on Foster and Pulaski because it was so close to the Bohemian National cemetery, where Bernard was buried, and because there were so many residents with whom she could speak Czech.

Tereza moved into the nursing home in 1993, at age 98. Her transition was relatively smooth, though she at first spent all of her time in her room, furiously crocheting. When the staff attempted to intervene and suggest that she limit the amount of time she spent crocheting so that she could meet other residents and participate in the facility’s activities, she grew angry and refused to crochet any more. She wanted complete control of her hobby, she said, or she didn’t want to do it all. She called Simon to come pick up all of her crochet materials and hasn’t engaged in this activity since, though many residents and staff have tried to persuade her otherwise.

Tereza did eventually begin to come out of her room and meet people, especially at the encouragement of Simon, who came to visit her two or three times each week for over a year. Tereza and Simon seemed to have a very special relationship, and in particular, he has always been a calming influence. On his visits to the nursing home, he often took Tereza walking in the facility’s gardens and would sit outdoors with her, just talking or laughing. He was always able to understand her and was likewise always able to get her to understand him, despite her hearing loss. According to Simon’s wife, Norma, the two of them had a strange connection in that he would always appear at the nursing home just when Tereza seemed to need him most.

Sadly for all, Simon passed away in 1994 of bone cancer. His dying request of Norma was to never tell Tereza that he had died—to keep his death from her. Norma and all the rest of the family agreed, though it has been very painful for them to keep up the pretense, even now. Norma and Rita still visit her, but not as much as Simon used to. When Tereza inevitably asks why Simon didn’t come, Norma lies and says he is at home in bed with a bad back. Tereza seems to accept this story, but she is always sad and worried about him, especially when he wasn’t there for her 100th birthday party. On that occasion, Norma told her that Simon had to stay home with the flu. It is a situation that neither Norma or Rita are comfortable with, but they don’t know what else to do.

Besides her worry about Simon, Tereza is seems happy. She is remarkably cognizant and able to get around on her own throughout the home. Her favorite activity is simply sitting and talking with other residents or watching Lawrence Welk on TV.

(Originally written: September 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Lived to be 100! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 23, 2023

The Colorful Life of Irene Diefenbach

Irene Diefenbach was born on September 2, 1910 in Pennsylvania to Slovak immigrants, Karol and Danica Dalibor. The Dalibors worked on a small dairy farm, but when Irene and her two siblings were still very young, the family moved to Phillips, Wisconsin, which had a large Slovak population and many dairy farms in the surrounding area. Karol was able to purchase his own farm there, which Danica helped to run.

Irene Diefenbach was born on September 2, 1910 in Pennsylvania to Slovak immigrants, Karol and Danica Dalibor. The Dalibors worked on a small dairy farm, but when Irene and her two siblings were still very young, the family moved to Phillips, Wisconsin, which had a large Slovak population and many dairy farms in the surrounding area. Karol was able to purchase his own farm there, which Danica helped to run.

Irene attended grammar and high school, but as there were few job prospects for her in Phillips, it was decided that she should go to Chicago to find work. Somehow it was arranged that Irene would work cleaning house for wealthy residents of the North Shore but would stay with an old German lady, a Mrs. Glockner, who lived on the South side. In her free time, Irene also attended a design school to learn how to design clothes. She became quite skilled at this and actually designed some dresses for Mrs. Glockner and her friends.

Irene was apparently very attractive in her day and had many beaux and would-be suitors. She was forever going on dates, and thus Mrs. Glockner established a protocol that Irene had to follow. Irene’s gentlemen callers were required to pick her up at Mrs. Glockner’s at exactly 6:15 and sit for a time and make polite conversation before they were allowed to leave. The next morning, Irene would then tell Mrs. Glockner all about her evening out, and then the two would proceed to discuss the pros and cons of each young man in question.

One time, so the story goes, Irene brought home a young man by the name of Gilbert Diefenbach, whom Irene thought so boring on their evening out that she didn’t even plan on discussing him at breakfast the next morning. So, she was surprised when Mrs. Glockner announced, based on her conversation with him the night before, that he was the one Irene should marry. Irene was stunned by this announcement, but she regarded Mrs. Glockner’s opinion so highly that she reluctantly gave Gilbert another chance. Apparently, he was not as boring on the second date, and they began seeing each other regularly. They eventually married in 1939 when Irene was 29 and Gilbert was 32.

The young couple moved to what was then a little country town called Mount Prospect, Il. and there had their first baby, Phyllis. Following Phyllis, Irene had three miscarriages before she finally gave birth to another daughter, June. Right at about this time, Irene’s parents’ health began to fail severely, and Karol found he could no longer farm. Gilbert himself had grown up on a farm, so he suggested that he and Irene and the two girls move up to Phillips to help her parents and to hopefully prevent the farm from being sold. Irene and Gilbert tried their best for four years to make the farm a success, but it was too difficult for Gilbert to do on his own, as they couldn’t afford to hire outside help.

Eventually, the farm had to be sold, and the Diefenbachs moved back to Chicago and found an apartment in Andersonville. The building they moved into was nicknamed “The Castle” and was very beautiful. The Diefenbachs rented the first floor apartment, which happened to be where the door to the cellar was located. Apparently, the woman who had previously owned the building had made her own liquors in the cellar during prohibition and had thus converted it into a huge wine cellar. When the woman vacated the building, she left behind all the wines and liquors, assuming they had all spoiled, as did everyone else. Irene, however, was determined to investigate and took great delight in finding many “hidden treasures.” As predicted, most of the wine had indeed spoiled, but she did come across some excellent cherry cordial. Irene discovered that they were an excellent vintage and that she used most of them as gifts over the years.

After June was born, the doctors told Irene that she shouldn’t have any more children, as it would be too risky, but seven years later, Sophie was unexpectedly born. Irene was happy staying home with her girls while Gilbert worked as an insurance salesman. Irene was a very active member of the community and of her church, St. Joan of Arc. She was a member of various groups at church, a ladies Slovak union, a neighborhood gardening club, and was a leader in the Girl Scouts. She designed and sewed all of her own clothes, as well as those of her daughters’, and loved dancing, music, and intellectual conversations.

Life went along swimmingly until 1963, which proved to be a difficult year for Irene. Not only did Gilbert pass away that year, but Phyllis got married and moved to New York. The following year, June got married and subsequently moved to Boston, leaving Irene and Sophie alone. At that point, Sophie was in high school, and Irene didn’t like sitting around the house by herself. She decided, then, to go back to work and easily got a job at Marshall Field’s doing alterations. In addition, she produced her own designs on the side and also worked as a swimming instructor. Later she left Fields for Carson’s, where she worked until 1970, when Sophie got married and moved away, too.

Irene was sixty when Sophie got married. She was quite willing to live independently, but Phyllis persuaded her to come and live with her and her husband, Dave, in New York, as she was worried about her mother living alone. Irene agreed to come, but she insisted on driving her car all the way to New York so that she would have a means of transportation at her disposal once she got there. Irene enjoyed New York, but after only a couple of years, however, Dave was transferred to Naperville, Illinois, causing all them to relocate yet again. Rather than again move in with Phyllis and Dave, however, Irene decided to get her own place at Four Lakes in Lisle, where she happily remained for fourteen years. In that time, Phyllis and Dave were transferred again, this time to Washington, but Irene remained behind in Lisle.

In 1980, Irene suffered a stroke, which paralyzed her whole right side. She was determined, though, “to make a comeback” and live independently. Amazingly, she did indeed learn to walk, read and write all over again and even managed to make a wedding dress for a family friend, a huge personal achievement.

Irene remained on her own until 1993 when she began to finally need more assistance. Sophie helped her to move into a retirement complex, but Irene hated it there. Though she herself was eighty-three, she was disgusted that she was surrounded by “old people” and became depressed. Her daughter, Sophie, believes that this was “the beginning of the end.” At the retirement home, Irene experienced six more mini-strokes and a seizure. Likewise, while attempting to get out of bed one morning, Irene fell and fractured several vertebrae. She was transferred to the hospital and then released to a nursing home under hospice care.

Irene is currently not able to communicate very well, though she seems alert. Sophie is convinced that her mother does not realize she is in a nursing home and that it would “instantly kill her” if she knew. Sophie is racked with guilt and sorrow regarding the whole situation and continuously urges the staff to provide intellectual stimulation for her mother. Irene, for her part, when awake, seems very pleasant and amiable and is happy with whatever is given to her. “She was a wonderful mother,” says Sophie. She was “everyone’s best friend.”

(Originally written: January 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Colorful Life of Irene Diefenbach appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 16, 2023

“It’s Not The Real Albert”

Albert Daelman was born on September 5, 1916 on a farm in LaSalle, Illinois to Ernst and Willemina Daelman, Dutch immigrants. Ernst was a farmer and was what Albert describes as “a hard-working man.” His mother, Willemina, cared for their six children. Albert managed to attend high school for a year and a half before he quit to get a job. When the WWII broke out, he enlisted in the army and was stationed in the Philippines.

Albert Daelman was born on September 5, 1916 on a farm in LaSalle, Illinois to Ernst and Willemina Daelman, Dutch immigrants. Ernst was a farmer and was what Albert describes as “a hard-working man.” His mother, Willemina, cared for their six children. Albert managed to attend high school for a year and a half before he quit to get a job. When the WWII broke out, he enlisted in the army and was stationed in the Philippines.

Upon being discharged and returning home, Albert decided to move to Chicago and found work as a machinist in various factories. At one point, he decided to take a vacation to San Francisco and happened to meet a beautiful young Mexican woman, Benita Caldera, who was also vacationing there. Albert took her out to dinner and afterwards asked her if he could write to her. Benita agreed to give him her address, though she had a boyfriend back in Mexico. She lived in a small town there and worked as a manager of a furniture store. She and her sister lived together with their invalid mother, whom they both took care of.

True to his word, Albert wrote to Benita as soon as he got back to Chicago and continued to write to her every week. The problem, however, was that his letters were mostly in English with a few Spanish words thrown in for good measure. Benita was unable to read them, so she had to have a friend or sometimes the parish priest interpret them for her. Pretty soon the whole village knew of Benita’s American “lover,” which prompted Benita to begin taking English lessons.

Things continued this way until Benita’s mother suddenly died, and Albert went to Mexico to attend the funeral. He stayed for two weeks, at Benita’s sister’s insistence, so that he could get a good picture, she said, of who they were and how they lived. It didn’t take long for Albert to propose to Benita, and she accepted him. At first they planned to get married in her local church, but Albert refused to pay the steep fee the parish priest was requiring, so they went to Chicago and got married at St. Viator’s.

Benita tried hard to adjust to her new life in America, but it was difficult at first. She says that a German couple who lived next to them were very kind to her, but even so, each evening she would sneak out onto the porch and cry with homesickness. Eventually Benita got used to being Albert’s wife, however, and things settled down. She managed to get a job working in accounting at the Lions International Headquarters, and Albert continued working as a machinist, his longest employment being with Victor Products. They never had any children, though Benita says she would have liked to.

Benita vehemently states that Albert was “a good, good man—an honest man,” but, she adds, “he was not very friendly.” Benita claims that Albert has always had “a complex” about being around people. He was very shy and nervous and angered easily. Benita says that he had no hobbies and no friends and dealt with stress by drinking a lot and complaining about every little thing.

His routine was to go out to the local tavern on Friday nights after work, where he proceeded to drink away the majority of his paycheck. When he came home drunk, Benita would put him to bed and then go through his pockets to see if there was any money left. This went on until he retired, and Benita finally persuaded Albert’s doctor to tell him that if he didn’t stop drinking he would die. Apparently, this convinced Albert, and he stopped drinking cold turkey. Albert went on to get a job as a security guard at Colonial Bank on Belmont, where he worked for five years until he was diagnosed with lung cancer.

Despite having treatments, Albert’s lung cancer spread to his brain, which caused disorientation, confusion, and a shift in personality. Benita tried to care for him at home for several years, but when Albert became at times verbally and possibly physically abusive to her, she could no longer cope. Not knowing what else to do, Benita recently placed him in a nursing home, which he is not adjusting well to. He continually blames Benita for bringing him here and becomes agitated whenever she visits. Indeed, on one occasion, he attempted to strangle her. His two obsessions seem to be sneaking off to bed or repeatedly saying “get me out of here.”

All of this is particularly hard on Benita, who claims that she loves him still, despite his verbal abuse. “It is not the real Albert,” she says, and is overwhelmed with grief and guilt that she cannot help him more.

(Originally written: March 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “It’s Not The Real Albert” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 9, 2023

“Jesus Has Always Been With Me”

Celina Abelli was born on August 18, 1898 in a small Polish village to Wera Pakulski and Olek Zuraw. Celina says the family lived on a farm with beautiful fruit trees. Besides farming, Olek worked as a carpenter and even built the house they lived in. In addition, he cut and sold logs from a nearby forest and helped cut hay on local farms for extra money. Wera, meanwhile, cared for their six children: Zygfryd, Waldemar, Kaja, Helena, Teodor and Celina. Wera had a total of nine children, but three died of typhus fever before Celina was born: Konrad, who was seven when he died, and Lew and Marek, who were twin baby boys.

Celina Abelli was born on August 18, 1898 in a small Polish village to Wera Pakulski and Olek Zuraw. Celina says the family lived on a farm with beautiful fruit trees. Besides farming, Olek worked as a carpenter and even built the house they lived in. In addition, he cut and sold logs from a nearby forest and helped cut hay on local farms for extra money. Wera, meanwhile, cared for their six children: Zygfryd, Waldemar, Kaja, Helena, Teodor and Celina. Wera had a total of nine children, but three died of typhus fever before Celina was born: Konrad, who was seven when he died, and Lew and Marek, who were twin baby boys.

When Celina was just four and a half, Olek died at age forty-four of pneumonia. Celina has just one memory of him, which was of him lifting her up into the fruit trees to pick a piece of fruit for herself. After Olek’s death, all of the children had to find work, except Teodor and Celina who were too young. Both of them continued at school for a few years and then also quit. Celina found work sewing or doing “any little thing that came along.”

The siblings all worked hard, and occassionally Wera allowed them to go into town to attend dances in the evenings. It was at one such dance that Celina’s sister, Kaja, met a young man by the name of Emil Brzezicki. Unfortunately, however, Emil only had eyes for Celina, who for some reason instantly hated him. Emil wouldn’t give up, however, and began following Celina everywhere she went, even bringing her flowers on many occasions, much to Celina’s embarrassment and Kaja’s despair. Celina won’t say exactly why she didn’t initially like Emil, nor has she ever said why she eventually agreed to marry him. No one in the family can shed any light on why Celina changed her mind, though her daughters suspect that something dark may have happened. When asked if she grew to love Emil, Celina says, “I didn’t hate him, but I didn’t love him, either. It was something in between. We got by.”

After they were married, Celina and Emil lived with Wera before eventually moving to a neighboring town a year later. Together, they had eight children, but two died when they were small. Celina doesn’t have much to say about their life in Poland during the 1930s and ’40s, or how they survived the war, just that after it was over, the whole family moved to America around 1950. One of their sons, Simon, was delayed in Poland for a time, but he eventually joined the family in Chicago, which is where they eventually settled. He left again almost immediately, however, to join the American army.

In Chicago, Emil found work in a furniture factory, but he had to quit after only four years because he was diagnosed with emphysema. Realizing that Emil’s prognosis was not good, Celina knew she had to find some sort of employment and managed to buy a little corner grocery shop. She ran the store and nursed Emil, who eventually died seven years later in 1961. Celina kept the store running even after Emil died, but she says it was hard because it was the era when big chain grocery stores were buying up all the little neighborhood shops. After two years, she gave in as well and sold it. After that, she found work as a nurse’s aide.

In 1970, Celina married again—this time to a quiet, mild-mannered Italian man, Stefano Abelli, who was eight years her senior. She says she loved Stefano, but when asked about their relationship, she says, “Well, it wasn’t sweet 16!” Celina and Stefano’s relationship was short-lived, however, as Stefano died of cancer after only a year and a half of marriage. Following his death, Celina lived alone for many years. Two of her daughters died—one of a heart attack at age fifty-five and one of cancer in her forties. Her other four children are scattered in other parts of the country, so that as her health has begun to decline, Celina has been relying more and more on her grandchildren who still live in the area.

In just the last couple of years, Celina has had a stroke and fractured her spine, among other things, which has caused her to have to live with various grandchildren. When she needed an operation on her leg, however, she was hospitalized and from there sent to a nursing home to recuperate. She wishes she could go home to one of her grandchildren’s houses, but she realizes this is unrealistic. She is not making a smooth adjustment, however, and says she is in a lot of pain, calling out frequently because of it. However, if anyone sits and talks with her at length, even for an hour or longer, she never once complains of pain or cries out.

Celina says that she has no hobbies because she never had time for fun; she was always working. Occasionally she would go to a movie or listen to music, but her biggest interest was probably the church. She says that she can recite the whole mass in Polish without one mistake. Celina relates that she has always prayed from the time she was a little child and has gotten a lot of strength from prayer over the years. She says that “Jesus has always been with me,” and that “I’m very religious. Very deep. But I lost a lot of faith when I came here because it’s hard to stay religious in a country like this.” Indeed, she says that when she remembers how life used to be in Poland “I am bitter” and “I want to die.” She cries easily and seems particularly fixated on the 1986 space shuttle explosion.

Attempts have been made to involve her children in her care, but they are all older themselves and have their own health problems. One son recently sent her twenty dollars in a card, which Celina was thrilled with and proudly showed to all of the staff. Overall, however, Celina remains depressed and despondent, reluctant to start life over yet again.

(Originally written: April 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Jesus Has Always Been With Me” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 2, 2023

From Professional Waiter at the Drake Hotel to Navy Bartender

Gonzolo Rochez was born in Texas on February 2, 1908 to Fernando and Sonia Rochez. He likes to say that he was born “a few years” after the U.S. “took over” Texas from Mexico, though in reality, this event happened sixty years prior. According to Gonzolo, his parents died when he was five or six years old. He doesn’t remember them at all, nor does he know how they died. All he knows is that he was sent to live with his godmother in the same village, but she was old and poor and couldn’t really take care for him. Not knowing what else to do, she sent him to an orphanage run by nuns. Gonzolo hated life at the orphanage. He says that he was taught to read and write, but that he was always hungry, so he decided to run away. He became a street urchin, then, wandering from place to place and was constantly “bumped or kicked around.”

Gonzolo Rochez was born in Texas on February 2, 1908 to Fernando and Sonia Rochez. He likes to say that he was born “a few years” after the U.S. “took over” Texas from Mexico, though in reality, this event happened sixty years prior. According to Gonzolo, his parents died when he was five or six years old. He doesn’t remember them at all, nor does he know how they died. All he knows is that he was sent to live with his godmother in the same village, but she was old and poor and couldn’t really take care for him. Not knowing what else to do, she sent him to an orphanage run by nuns. Gonzolo hated life at the orphanage. He says that he was taught to read and write, but that he was always hungry, so he decided to run away. He became a street urchin, then, wandering from place to place and was constantly “bumped or kicked around.”

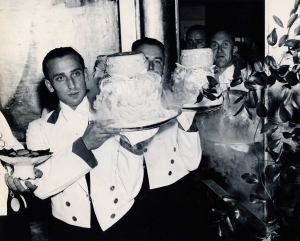

In his late teens or early twenties, Gonzolo made his way to Chicago with a few friends, where he found a job in a restaurant. Eventually, he found a place to live as well and sent for his girlfriend, Angelina Poblete, back in Texas to join him. Gonzolo and Angelina soon married, and Gonzolo began to look for a better job. Gonzolo eventually landed a position at the Drake Hotel—“the best of the best”—where he earnestly began to “learn the trade” of being a professional waiter. For forty years, he worked as a waiter at only the best hotels: the Drake, The Blackstone, The Congress, and the Ritz-Carlton. Gonzolo says of this time period: “I was healthy, I didn’t complain, and I made a living.”

It was also during this time that he took up the hobby of painting. He remembers one weekend when he happened to be walking around State Street and saw a painter painting the crowd. Looking over the painter’s shoulder, he decided it didn’t look that hard, so he went to a dime store and bought some paint and brushes. He was impressed with what he produced and took up painting in earnest. It became his life-long hobby. Apparently, a wealthy business man who once saw Gonzolo’s paintings offered to pay for him to take art classes, but Gonzolo refused his offer, saying, “I want to paint what I want to paint, not what they tell me.” Gonzolo claims that both the Drake and the Congress Hotels possess some of his artwork.

When WWII broke out, Gonzolo joined the navy and was stationed for four years in Ottumwa, Iowa, where he quickly became the company bartender. He was apparently liked by everyone, especially the officers, and was “treated very well.” He and three other men became “untouchable” because they were well-liked by the officers and were therefore given special favors. He once confided to an officer, however, that he didn’t feel like he was doing much to help the war effort and worried what he would tell people back home. The officer assured him that he was “helping as much or more with morale.” Gonzolo says that those four years in the navy were the best of his life. He would have stayed in if he didn’t have Angelina and two children, David and Eva, waiting back at home for him. Only occasionally did he go back to visit them, and when his four years of service were up, he reluctantly returned to Chicago and continued on with his career as a waiter.

Being away for four years did not improve what was already a rocky marriage between him and Angelina. Gonzolo’s daughter, Eva, reports that he was a terrible husband and father. She claims that Gonzolo was a very controlling, domineering, manipulative man who beat Angelina and David, but never her. The story of refusing art classes, she says, proves how much control he needed, that he would never subject himself to any outside authority. “No one could tell him what to do,” Eva says. This is why, she relates, he would never belong to a church. He was baptized Catholic, but doesn’t believe in God. It is Gonzolo’s belief that “religion is an invisible weapon of the government to control the masses.” Instead, he says he believes in “the supernatural power of the universe” and that “when you die, you go to the same place you go to when you sleep.” Because of his hot tempter, Eva claims that her father did not have any friends, at least that she knows of. Indeed, when asked about any significant friendships he has had in the past, Gonzolo answers that “friends are make believe.” When asked how he has coped with problems over the years, he says simply, “I never had any problems.”

Angelina died in the late 1980’s, so Eva has been caring for Gonzolo on and off over the last several years. David has been estranged from his father for the past twenty years and lives somewhere in California. When Gonzolo’s health began to fail recently, Eva took him in to her own home for a time, but quickly realized she could not endure his domineering, manipulative ways and brought him to a nursing home.

Gonzolo has not made the transition well and remains very depressed. “Why should I get better?” he asks. “So I can plunge down again? I’m old. I’m 88 years old. I’ve had a terrible life. Let me die.” He has not participated in many activities, nor does he seem interested in forming any relationships with the other residents. His favorite thing is to do is to talk about the past with the staff. He admits to liking to learn new things, however, which he says he has always tried to do throughout his life. “It’s not hard to learn if you’re willing,” he says.

(Originally written: April 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post From Professional Waiter at the Drake Hotel to Navy Bartender appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 23, 2023

She Worked Until She Was 80!

Hedda Woods was born in Chicago on October 25, 1905 to Ulla Ostberg and Birger Haugen, both immigrants from Norway. Soon after they married in Alesund, Norway, Ulla and Birger decided to come to America to try a new life. Family legend has it that when they came through Ellis Island, Ulla, the stronger of the pair, herself carried their trunk on her back! From Ellis Island, the Haugen’s made their way to the west side of Chicago. Birger got a job “working with figures,” meaning he was a sort of draftsman and designed machinery. Ulla cared for their seven children: Signe, Carl, Egil, Tanja, Erling, Finn and Hedda, all of whom survived childhood.

Hedda Woods was born in Chicago on October 25, 1905 to Ulla Ostberg and Birger Haugen, both immigrants from Norway. Soon after they married in Alesund, Norway, Ulla and Birger decided to come to America to try a new life. Family legend has it that when they came through Ellis Island, Ulla, the stronger of the pair, herself carried their trunk on her back! From Ellis Island, the Haugen’s made their way to the west side of Chicago. Birger got a job “working with figures,” meaning he was a sort of draftsman and designed machinery. Ulla cared for their seven children: Signe, Carl, Egil, Tanja, Erling, Finn and Hedda, all of whom survived childhood.

Hedda was the youngest and says that she usually got her way, being a very stubborn child. She graduated from Austin High School and got a job as a secretary for the Pullman Railroad Company. From there she went to work for Great Western and then to the Milwaukee Railroad Company, where she worked until she was sixty-five. According to her nephew, Dennis, Hedda always took her job very seriously. She worked hard and was always on the lookout for ways to advance herself, both professionally and personally.

Birger passed away around 1932, and Ulla died nearly twenty years later in the 1950’s. At the time, Finn, Erling, Tanja and Hedda were still living at home, so they continued on this way, even after both parents died. It was right about this time, however, that Hedda met a man by the name of Dr. Nelson Woods at a dance. Hedda says that the group of friends she was with that night met up with another group, of which Nelson happened to be a part. The two hit it off right away and began dating. When Hedda was forty-six, the two married and bought a home in Elmwood Park.

Hedda kept their house “neat as a pin” and joined many women’s groups, such as the Eastern Star, the 19th Century Women’s Group of Oak Park, and the Lyden Township Women’s Group. She also loved art, music, sewing, dancing and was a very good cook. Dennis reports that his aunt was an extremely intelligent woman but was stubborn and had a razor sharp tongue. Hedda was confirmed a Lutheran as a girl, but she later in life joined the Christian Science Church in Oak Park. Hedda and Nelson never had any children, and they apparently had a very happy marriage. They traveled all over the United States on vacations or attending conventions.

Hedda retired from the Milwaukee Railroad Company at age sixty-five. Her last day was on a Friday, and on the following Monday, she started at a new job at Continental Bank in the “corporate art” department. Apparently, the bank, or a division of the bank, owned a large collection of paintings, sculpture and select pieces of fine art that they rented out to various companies. Hedda was put in charge of this department and really loved it. She continued working in this position until she was eighty years old!

Even after Nelson died in 1978, when Hedda was seventy-three, she continued working. She made the decision to finally retire for good in 1985 when she was walking to work one morning. It so happened that as she was crossing a bridge over the Chicago River, a strong blast of wind whipped through and nearly blew her over. Hedda grabbed onto a man who was walking beside her and thus managed not to fall. She is convinced that if the man had not been there at that moment, she would have been blown into the river and drowned. It was then that she decided she “couldn’t go to work anymore,” but she continued to be very active in all of her women’s groups.

As time has gone on, however, Hedda has become more alienated from people, especially as her hearing has gotten worse, her memory more unreliable, and her tongue sharper. She also grew apart from her siblings over the years, despite many of them living in the Chicago area. She has only remained close to her sister, Signe, and Signe’s son, Dennis—her favorite nephew. Dennis says that he has gotten along with his aunt all these years because he has always been able to ignore her critical comments. He says that she is actually a very strong, spiritual woman who got through troublesome periods in her life with prayer.

In 1992, Hedda fell and broke her hip. At that point, Dennis helped her hire a live-in nurse, an arrangement that lasted almost four years, until Hedda’s finances were almost exhausted and she likewise required more care. In bringing her to a nursing home, Dennis’s hope is that she might regain some social involvement.

For her part, Hedda seems to enjoy talking with the other residents and is rarely anxious because each day she believes that Dennis is coming to pick her up and take her home. She is very forgetful, but she loves talking about the past, about which her memory appears to be crystal clear.

(Originally written: March 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Worked Until She Was 80! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.