Michelle Cox's Blog, page 5

September 14, 2023

“She Was Happiest With a Drink in Hand.”

Vlasta Di Stefano was born on January 21, 1910 in Chicago to Bela Hrabe and Lazar Dragic. Bela was an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Lazar emigrated from Yugoslavia. The two apparently met at Ellis Island and, though they initially went their separate ways, they wrote letters to each other for the next year or so. Eventually, they somehow met up again and married, settling in Chicago on Harding Avenue. After a few years, however, they left the city and moved to a farm in Minnesota. Besides farming, Lazar worked delivering lumber, and Bela cared for their seven children: Adam, Yvonne, Denis, Vlasta, Dusan, Emil and Pavla.

Vlasta Di Stefano was born on January 21, 1910 in Chicago to Bela Hrabe and Lazar Dragic. Bela was an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Lazar emigrated from Yugoslavia. The two apparently met at Ellis Island and, though they initially went their separate ways, they wrote letters to each other for the next year or so. Eventually, they somehow met up again and married, settling in Chicago on Harding Avenue. After a few years, however, they left the city and moved to a farm in Minnesota. Besides farming, Lazar worked delivering lumber, and Bela cared for their seven children: Adam, Yvonne, Denis, Vlasta, Dusan, Emil and Pavla.

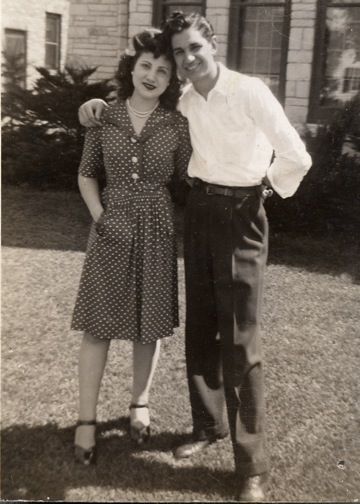

Vlasta attended grade school, but at age thirteen, she decided to move back to Chicago, where her older sister, Yvonne, and her husband had since moved to. Vlasta lived with them and got a job at Union Linen Supply and there met her future husband, Ruben Alvardo, a Mexican immigrant. Ruben liked Vlasta immediately and often took her on picnics to a picnic grove at Devon and Milwaukee, which, at that time, was still a wooded, rural area. He eventually proposed to Vlasta, and they married when she was just nineteen.

Ruben continued working at Union Linen, but Vlasta quit once she became pregnant with their first child. Ruben and Vlasta had a total of six children: Viola, Kenneth, Raymond, Carol, Dolores and Jerry. When Jerry was a toddler, Vlasta decided to go back to work. Union Linen Supply had no openings, however, so she instead got a job at a company called Cromane, which did silver plating.

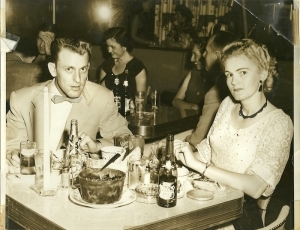

According to her daughter, Viola, Ruben and Vlasta were very private people. They did not have friends, nor did they associate with either of their families. They even refused to go to any school functions, including their own children’s graduations or holiday shows. Their only pastime, says Viola, was drinking. In fact, when Vlasta decided to return to work, she apparently dumped all of the household cleaning, management and cooking unto Viola, who was roughly eleven at the time. From that point on, Viola became the mother-figure for the whole family and remains so even today.

Tragically, in July of 1950, Ruben was hit by a car and killed while walking home from work. He was not yet 50 years old. Vlasta continued working, doing her best to make ends meet and eventually met and married David Di Stefano. She only had about ten years with David, however, before he died of cancer. After that, Vlasta lived alone, watching her neighborhood slowly decline, and was attacked twice coming home from the shops. She put her name in to get a place in North Park Village, but had to wait ten years for a spot to open up.

When Vlasta did finally move into the North Park Village senior apartments about seven years ago, she was still relatively independent, but as time has gone on, she has relied more and more on Viola to again help her with cleaning, laundry and shopping. Recently, though, things have become worse, with Vlasta not being able to care for herself at all. Viola has been in the habit for the last several months of going to Vlasta’s apartment twice a day to feed her and clean up urine and feces that is usually found on the floor or furniture. Viola has been beside herself with worry, as she has often come to the apartment and found the stove on and pans burnt through. Fearing that she would possibly have a nervous breakdown from the stress of the situation, Viola finally decided to admit Vlasta to a nursing home.

Viola, in the role of mother since age eleven, feels incredible guilt at not being able to still care for Vlasta, but they are both adjusting well to the new arrangement. Viola predicted that Vlasta would be extremely angry at being placed in a home, and was therefore pleasantly surprised by Vlasta’s easy transition. Vlasta is confused at times and does not talk a lot, but she enjoys sitting among the other residents. Though not always eager to participate in activities, she very much likes to watch what is going on, perhaps a life-long behavior. Viola claims that her mother never had any hobbies and never wanted to “get involved.” She says that Vlasta watched everything from afar. She was content, but “never really that happy, even on birthdays or holidays.” She was “very much a loner and had a hard time fitting in.” She was happiest, Viola claims, when she “had a drink in her hand.”

(Originally written May 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “She Was Happiest With a Drink in Hand.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

September 7, 2023

“He Was Never The Same.”

Felix Dubicki was born on July 12, 1928 in Chicago to Izaak Dubicki and Anontia Grzeskiewicz, both immigrants from Poland. It is thought that Izaak and Antonia met and married in Chicago, but Felix isn’t sure. He knows that his father worked in Chicago at a tannery and that his mother cared for their four children: Andrew, Danuta, Felix and Felicia.

Felix Dubicki was born on July 12, 1928 in Chicago to Izaak Dubicki and Anontia Grzeskiewicz, both immigrants from Poland. It is thought that Izaak and Antonia met and married in Chicago, but Felix isn’t sure. He knows that his father worked in Chicago at a tannery and that his mother cared for their four children: Andrew, Danuta, Felix and Felicia.

Felix does not recall much about his parents, but his sister, Felicia, relates that Izaak and Antonia “suffered many hardships” in Poland and that they were very poor. According to Felicia, they had “a different mindset, a different outlook on life.” Children were not beloved priorities to them, but were instead seen as accidents. For Izaak and Antonia, life was not about providing a loving, happy environment for their children, it was about surviving, and each child that came along made surviving that much harder. Felix is especially bitter about his childhood and says that he has no deep love for his parents.

Felicia explains that this is probably because when she was eleven and Felix was twelve, Izaak and Antonia divorced. Andrew and Danuta were old enough, apparently, to fend for themselves, but Felix and Felicia were sent by their parents to live in an orphanage. Felicia says that though it was difficult, she managed to make it through relatively unscathed. Felix, on the other hand, was quickly nicknamed “Jammy” by the other orphans because he was always getting himself into “jams” and subsequently punished. According to Felicia, Felix was a very outgoing, fun-loving child, but after his experience at the orphanage, he “crawled into a shell” and became very quiet and introverted for the rest of his life.

After several years, Antonia was financially stable enough to bring Felicia and Felix back home to live with her and enrolled them in high school. After only two years, though, Felix came down with rheumatic fever and had to quit. When he eventually recovered, he gave up school altogether and became what was known as a paper handler in a printing company called Chicago Roller Print on Fulton Street.

Felix continued to live with his mother, even after Felicia married and moved out. Eventually, however, Felix moved into his own apartment because Antonia was “too hard to take,” though he continued to financially support her. Felicia confirms that Antonia was a very difficult person to get along with. Once he was on his own, Felix began to drift from the family and became more and more of an introvert. Even Felicia, to whom he was the closest, lost contact with him. Life continued this way for the next twenty years, with Felix living a separate existence from his family. He never married, and Felicia says she never knew him to ever even have a girlfriend.

Over the years, Felix continued working for various print shops, including the Sun Times, the Tribune and Irving Berlin Press. His passions in life seemed to have been listening to opera, watching football, and going to the Lincoln Park Zoo. He apparently visited the zoo almost every day, saying that he much preferred the company of animals to humans. In his late forties, however, he did finally reach out to Felicia, who was surprised but happy that he had contacted her. Over the next decade, they had sporadic communication, Felicia suspecting that not only was she his only friend during those years but that he was an alcoholic as well.

When Felix was 55 years old, he was diagnosed with diabetes and was unable to work for a significant period of time. Unfortunately, this coincided with a shift that was occurring in the printing industry as a whole. It was becoming more and more automated, almost eliminating the need for manual paper handlers; thus, when he was able to return to work, Felix found himself without a job to go back to. Not knowing what else to do and still suffering from complications due to his diabetes, Felix went to live with Felicia. Felicia reports that in the beginning, when he was only receiving a small unemployment check, his drinking subsided significantly, but then when he began receiving larger disability checks, he went back to drinking heavily.

Felicia says that having Felix live with her wasn’t too much of a burden, as he stayed mostly in his room. He seemed depressed and unhappy most of the time, and she suspects that in 1993 he may have even tried to kill himself. Felicia does not elaborate on the details of what exactly happened, but says that Felix wound up in the hospital and was then discharged to a nursing home. He stayed in that particular facility for about a year before returning to live with Felicia. It was short-lived, however, because he needed so much more assistance than he had before, and Felicia, herself getting up in years, couldn’t help him or afford to hire anyone.

Felix was determined to not go back to a nursing home, however, so he decided to move into the Lorali apartments on Lawrence Avenue on his own. This arrangement only lasted about three days, however, before he became dizzy and fell. Felicia says it is probably because he didn’t eat right. His eyesight, she says, was also so bad at that point that he could not correctly read the numbers on his insulin syringe. When admitted to the hospital again, his numbers were so severely off that his doctor would only agree to release him to a nursing home, saying that he was lucky to even be alive.

Felix has thus far made a relatively smooth transition to his new placement, but he remains quiet and withdrawn. He never speaks to the other residents, even if they ask him a question. He appears “in his own world,” much of the time, something he has been doing since he was “a little kid,” Felicia says. Though it is hard for her to get around, Felicia visits regularly. She seems very concerned for Felix and thinks that he is still very depressed. She is at a loss on how to help him, however, saying that Felix “has never been happy.” He was happy as a little boy, she says, but having to go to the orphanage changed something in him. “He was never the same.”

(Originally written: July 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “He Was Never The Same.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 31, 2023

Many Sisters Named Aurora

Aurora Sienkiewicz was born on April 5, 1911 to Giovanni and Rosa Corvi, both of whom grew up in the same small village in Italy. Giovanni’s and Rosa’s families lived near each other, and the two of them often played together as children. The story goes that one day when Giovanni was passing by, Rosa pointed to him and told her mother that someday she was going to marry Giovanni. It was a prediction that came true, and when they both turned eighteen they married and soon had a son, Marco.

Aurora Sienkiewicz was born on April 5, 1911 to Giovanni and Rosa Corvi, both of whom grew up in the same small village in Italy. Giovanni’s and Rosa’s families lived near each other, and the two of them often played together as children. The story goes that one day when Giovanni was passing by, Rosa pointed to him and told her mother that someday she was going to marry Giovanni. It was a prediction that came true, and when they both turned eighteen they married and soon had a son, Marco.

Times were hard in the village, however, and there was little work. So when Marco was five years old, Giovanni decided to go to America to look for work and a new life for them. Once in New York, he happily soon found a job and then immediately sent for Rosa and Marco to join him. The two of them came by ship with many people from their village, so they were not alone on the journey. Once Rosa and Marco arrived in New York, Giovanni found them an apartment in Brooklyn. Rosa got pregnant several times, but she always miscarried. They were all girls, and Rosa named them all Aurora after Giovanni’s mother, as was the custom.

After a few years in New York, Giovanni got restless and moved the whole family to Louisiana, where another son, Frank, was born. Again, the family settled down, but unfortunately Giovanni could not find any work, so they decided to go to California. They took a train to Chicago and were delayed there for some reason for almost a weak. In that time, Giovanni stumbled upon a good-paying job at a cigar factory, so they decided to stay. Rosa also did piece work at home, mostly sewing buttons onto trousers. In Chicago, she was finally able to carry a girl to term and once again named her Aurora. Two years later, Rosa had her fourth and last child, Vincent.

Aurora went to school through the 8th grade and then got a job in a paper box factory at age fourteen. She worked in various factories during her teen years, but she especially liked working at a stencil factory because they got to use chemicals. She found chemistry very interesting, and she became friends with one of the factory chemists, John Petronka. Aurora says that she is pretty sure John had a crush on her, but he was already engaged to someone else. Thus, he introduced her to his good friend, Thaddeus Sienkiewicz. The two of them hit it off right away, and after dating for just six months, Thaddeus proposed. Both Giovanni and Rosa were not thrilled about their only daughter marrying a Pole instead of an Italian, but they allowed them to get married anyway.

Thaddeus worked for Western Oil, a job he kept for forty-five years, and Aurora stayed home to care for their four children: Gloria, Phyllis and the twins, Roman and Roy. Like her mother before her, Aurora had many miscarriages over the years, and finally, after the twins were born, her doctor advised her to have a hysterectomy, to which Aurora agreed. When all of the children were in school, Aurora decided to go back to work and got a job as a kitchen aide in various hospitals.

Sadly, Aurora’s marriage was not a happy one, as Thaddeus turned out to be an alcoholic. Aurora says that this is why she was always a loner and had no friends or hobbies. “I had too many problems at home to worry about,” she says of that time. Having no one else to turn to, Aurora would sometimes confide in her mother, Rosa, regarding her marital woes, but Rosa, and Giovanni, as well, refused to ever talk badly about Thaddeus. “We told you you should marry an Italian,” they often scolded her, and told her that she would just have to put up with it.

Finally, however, Aurora could no longer stand to witness how Thaddeus’s behavior was affecting the children, so she separated from him. It was an extremely difficult thing to do, especially as her parents disapproved of divorce. They refused to support her, either financially or emotionally. Thaddeus moved into his own apartment, and though Aurora had some contact with him over the years, she pretty much raised the family on her own.

After her divorce, Aurora still stayed home much of the time in the evenings, but felt freer to make friends and invite them over. Occasionally, she would venture out to a movie or bingo at St. Philips, where she was a faithful parishioner. Only once did she take a trip, which was to go to California to see her brother, Vincent. She continued working as a kitchen aide until she was in her sixties.

When Aurora was in her mid-seventies, her son, Roman, died at age forty-five of complications due to his colitis condition. He was not married, and “didn’t take care of himself as he should have,” Aurora explains. “He lost the will to live.” Aurora was nearly broken by his death and refused to ever speak his name after the funeral was over. She still mourns him even now, she says.

Up until very recently, Aurora was living alone and was still active and able to care for herself. About a year ago, however, she had a small stroke and fell. As Phyllis is the only one of Aurora’s children still living in the area, much of the burden of caring for Aurora fell to her. The staff at the hospital suggested that Aurora be discharged to a nursing home, and Aurora reluctantly agreed with this decision.

While Aurora seems resigned to her fate, Phyllis does not. Because of her own health problems, she cannot care for Aurora at home and seems to feel very guilty about this. In just the last year, Phyllis has changed nursing homes for Aurora three times, as Phyllis—not necessarily Aurora—has been very unhappy with each placement, including the current one. Phyllis frequently lashes out at the staff, accusing them of a variety of things and can even be verbally abusive at times. Already she has threatened to remove Aurora yet again.

Meanwhile, Aurora seems not aware of Phyllis’s distress. She appears to be content, her favorite activity being bingo. At times she is confused and believes that her clothes are missing, which causes her to complain repeatedly to the staff. Once she becomes upset, she then tends to bring up Thaddeus and the anger she still feels towards him. “He’s living alone, free and easy, and here I am!” she will say, over and over. Normally, however, she is a pleasant woman who enjoys having conversations with the other residents or watching TV with them.

(Originally written August 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Many Sisters Named Aurora appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 24, 2023

“I Didn’t Have the Best Life, But I Made It.”

Chester Williamson was born on July 18, 1930 in Greenwood, Mississippi to Walter Williamson and Ethel Jones. In the early 1940’s, the family moved to Chicago to look for work. Walter found a job working in a steel mill during the day and later started working in a restaurant at night. Ethel, meanwhile, cared for their nine children: Walter, Jr.; Hattie; Clarence; Clara; Jimmy; Odelia; Roberta; Chester; and Roy.

Chester Williamson was born on July 18, 1930 in Greenwood, Mississippi to Walter Williamson and Ethel Jones. In the early 1940’s, the family moved to Chicago to look for work. Walter found a job working in a steel mill during the day and later started working in a restaurant at night. Ethel, meanwhile, cared for their nine children: Walter, Jr.; Hattie; Clarence; Clara; Jimmy; Odelia; Roberta; Chester; and Roy.

The Williamsons moved around the city a lot as Chester was growing up, never staying in any one apartment for long. Chester struggled with school, and finally, after sixth grade, he quit. He couldn’t find a job, however, and spent his days roaming the streets and getting into trouble. He was eventually arrested and sent to the state penitentiary until he was released in 1951 at age twenty-one.

Right about this time, Chester unfortunately discovered that he had some sort of infection in his right lung, which resulted in having part of it removed. After he recovered, he realized that he would never be able to get a job doing hard manual labor, so he enrolled in barber school. After a year, he earned his barber certificate and proceeded to find work at different shops around the South Side. Eventually, he was introduced to a young woman by the name of Lorraine Davis, who was the sister of one of his customers. Chester and Lorraine hit it off right away and married soon after. They moved into one of the newly built high-rises of Cabrini-Green and had twin girls: Sandra and Suzanne.

Chester says he was happy with Lorraine overall, but “something inside me just couldn’t stick” to any one person or thing. He eventually left Lorraine and became what he calls “a floater.” He went from place to place for a couple of years before he realized that he still loved Lorraine. It was too late, however, because when he finally decided to return to her, he discovered that she had already filed for divorce.

Brokenhearted, Chester went back to his “floating” lifestyle for the next thirty years, spending his time at the racetrack, listening to music in clubs, and traveling throughout the US and Canada. He had some contact with Lorraine and his girls over the years, but not much. To his knowledge, Lorraine is still living in Cabrini-Green, and he knows he has at least one granddaughter.

In the early ‘80’s, after a lifetime of working on and off in various barber shops, Chester decided that he really wanted to have his own shop. He hadn’t the slightest idea of how to go about it, though, nor anyone to consult with. He was determined, however, perhaps for the first time in his life, so he began the long process of waiting in line, filling out forms, getting approvals, and passing inspections to make his dream come true. Finally, after a couple of years of “getting organized,” he was able to open “Chester’s Cuts” on Broadway.

Chester’s Cuts was apparently a success, and Chester eventually expanded it into a neighboring storefront. After seven or eight years, however, it got to be a little too much for him, and he began to struggle with managing everything. When he fell and broke his hip in the early ‘90’s and the building owner simultaneously raised his rent, Chester decided to give it all up and sell the shop. With the little money he made from the sale, he decided to move into a retirement community in the suburbs, where it was discovered he had kidney failure due to his lifetime use of alcohol.

Chester remained at the retirement home for about a year before deciding to move into a nursing home back in the city. So far Chester has made a relatively smooth transition and gets along well with his roommate, Mr. Kim. Chester says that he dealt with stress throughout his life by drinking, but at some point he realized that stress and alcohol will always be around, so he had to make a conscious decision to quit. He says the key to success is to “approach things honestly.”

So far no family members have come forward to visit Chester, though he hopes his sister, Clara, his only living sibling of the original nine, will appear at some point.

Chester is extremely proud of the fact that he owned a barbershop, that he persevered through so much to attain it. Upon reflection, he says, “I didn’t have the best life, but I made it.”

(Originally written: August 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “I Didn’t Have the Best Life, But I Made It.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 17, 2023

“He’s All I Have”

Frieda McLeod was born on April 9, 1917 in Chicago to Robert Curran and Eileen Walsh, both immigrants from Ireland who came looking for a new life. Robert found work on the railroads and also delivering coal and flour, while Eileen worked as a cleaning lady in private homes and cared for their five children: Ruth, Charlie, Mary, Frieda and Ina.

Frieda McLeod was born on April 9, 1917 in Chicago to Robert Curran and Eileen Walsh, both immigrants from Ireland who came looking for a new life. Robert found work on the railroads and also delivering coal and flour, while Eileen worked as a cleaning lady in private homes and cared for their five children: Ruth, Charlie, Mary, Frieda and Ina.

Tragically, when Frieda was just five years old, Eileen contracted tuberculosis and died at age thirty-seven, shortly after giving birth to Ina. Grief-stricken, Robert “fell apart” and was unable to cope with caring for the family. For one thing, shortly after Eileen died, Ruth, the oldest child, began having seizures. The doctors that attended her diagnosed her as having a mental illness, and she was accordingly sent to a mental asylum. Close to a break down himself, Robert then sent Charlie to a foster home and likewise sent Mary and Frieda to go live at the Sisters of Mercy Home in Des Plaines. Poor little Ina languished in the hospital for over two years before she was well enough to be released. Instead of bringing her home, however, Robert arranged for her to be put directly into foster care.

Mary apparently hated living at the Sisters of Mercy and begged her father to be put in foster care instead, which he eventually agreed to. Freida, however, was only five when she went to the Sisters of Mercy and didn’t mind it. She stayed until she was eighteen. She graduated from 8th grade and then pursued a two-year business degree while there. She only remembers her father coming to see her once.

Upon graduation, she left the Sisters and got a job working at Navy Pier as a secretary in the WPA offices. Frieda enjoyed her new surroundings and her new freedom very much. Through friends, she was eventually introduced to a man by the name of Guy Knowles. Guy was an engineer in his thirties, and though Frieda was very much his junior, they began dating. Frieda fell in love with him very quickly, and she was still just eighteen when they married. They had a baby, Dewey, together, but the marriage soured soon after that. Apparently, Guy had been married several times before and found it hard to stay with one woman. When Dewey was just 18 months old, Guy left to pursue a “business opportunity” in Connecticut, leaving Frieda and Dewey to fend for themselves.

In desperation, Frieda turned to her sister, Mary, and went to live with her. She and Dewey remained at Mary’s for several years, Frieda taking jobs in various factories and offices until she landed a job at Sears, Roebuck, where she remained for over thirteen years. It was extremely difficult to care for Dewey and work full time, however, especially during the war years, so Frieda eventually placed him in foster care until she could manage better.

Frieda eventually remarried, this time to a man named Roland Cooke, who worked as a mechanic. Frieda sent for Dewey to come home and live with them, but he had a hard time adjusting to life with his new stepfather, who turned out to be an alcoholic and abusive. Dewey became a delinquent and was frequently in trouble with the police. He began taking drugs and became addicted to heroin. Finally, he was put into a series of juvenile homes until he became an adult and was then sent to prison. Dewey admits that he has led “a bad life” and regrets that he caused Frieda so much grief over the years.

Frieda, he says, has “a heart of gold,” and despite all of her own troubles and poverty through the years, always had an open-door policy. Dewey remembers that their house was always open to anyone who needed a place to stay until they could get back on their feet again. Frieda, he says, was a true “good Samaritan,” never worrying about herself.

Frieda eventually divorced Roland and then married Gordon McLeod, a retired fire lieutenant, but that marriage, too, broke up after only a few years. Frieda then went to live with her sister, Ina, for a little while and from there moved in with Dewey, who had an apartment on Mozart. For the few years they lived together on Mozart, Frieda and Dewey seemed to have gotten along, their favorite pastime being to go and watch various Chicago sporting events. Frieda is a big fan of all the Chicago teams: Bears, Bulls, Blackhawks, Cubs, and Sox and would go to see any of them at any time.

Eventually, however, Frieda’s declining health got to be too much for Dewey to handle, considering his own long list of problems and issues. Somehow the State Guardian’s office got involved in Frieda’s case and appointed her a public guardian, a Ms. Karen Vargos. Ms. Vargos assisted in arranging for Frieda’s admission to a nursing home, where she has resided for about six months.

Frieda is a quiet, pleasant woman, but she appears depressed and apathetic. She has no interest in forming any new relationships or joining in any activities, nor does she really seem to want to converse with the staff. She enjoys smoking and watching sports on TV and waits for Dewey’s visits, which are infrequent. She misses him, she says. “I know he wasn’t a very good son,” she says, “but he’s all I have.”

(Originally written January 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “He’s All I Have” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 10, 2023

Surrounded by Angels…And One Devil

Gerald “Jerry” Dziedzic was born on October 25, 1909 in Braddock, Pennsylvania to Wojtek and Paula Dziedzic, both immigrants from Poland. Not much is known about Jerry’s early life, except that he was the youngest of seven children and that his father worked as a laborer in a factory.

Gerald “Jerry” Dziedzic was born on October 25, 1909 in Braddock, Pennsylvania to Wojtek and Paula Dziedzic, both immigrants from Poland. Not much is known about Jerry’s early life, except that he was the youngest of seven children and that his father worked as a laborer in a factory.

Jerry went to school on and off until the eighth grade, and, later, as a young man, somehow made his way to Chicago to find work. He ended up working south of the city, which at that time was still farm land. He met Flora Glab at a baseball game, and the two married a few months later. None of Jerry’s family even knew about the happy event and thus did not attend.

Jerry found work at a trucking company, and Flora worked in a radio factory until their first child, Marjorie, was born. According to Jerry, Flora “wasn’t quite right” after Marjorie’s birth and became very unhappy. Within months, she packed up her things and the baby and left Jerry, though he never really understood why.

Flora did not tell Jerry where she went, but he attempted over the years to trace her or Marjorie. He eventually found out that Flora had placed Marjorie in foster care when she was very young and that Flora herself had since died. Marjorie was fifteen by the time Jerry finally located her. He applied to have her come and live with him and his new wife, Lillian Novotny. Jerry hoped to make up for all of the lost years, but Marjorie was shockingly disruptive and “wild” and very antagonistic to Lillian. Eventually, Lillian could no longer take Marjorie’s antics and threatened to divorce Jerry if he didn’t do something with his daughter. Jerry, not wanting to estrange his daughter after all these years, chose to do nothing, so Lillian left him. Jerry then tried to build a new life with Marjorie, but as soon as she was eighteen, she got married and moved away. After she left, Jerry lived alone for many years and worked as a truck driver.

For a long time, Jerry’s only friend was a Greek woman by the name of Dora Simonides, who lived in the apartment next to him. Dora apparently had problems with her children as well, and she and Jerry often commiserated together and occasionally went out to keep from being lonely. One day out of the blue, Dora asked Jerry to marry her, and he said yes. The two friends did not have much time together, however, before Dora was diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s. Jerry tried to care for her on his own, but it eventually got to be too much. So with a heavy heart, he admitted her to a nursing home, at which point Marjorie reappeared after being absent from Jerry’s life for years. She had apparently heard of her father’s remarriage and Dora’s admission to a home and had thus turned up to demand her share of her father’s money before it was “sucked up” by Dora’s nursing home expenses.

Wanting to please her and keep her in his life, Jerry agreed to give Marjorie $43,000 of his savings and to take Dora back home to care for her there rather than spending all of his and Dora’s—now Margorie’s—money on a nursing home. Jerry reluctantly cared for Dora as best he could, though he was seventy-eight himself, until Dora died in 1987. At the time, he was still working as a maintenance man at Lincoln West Hospital, where he had worked for over two decades. He finally retired when he was eighty, at which point, Marjorie convinced Jerry to move to a senior apartment, Lawrence House, and to buy her son, David, a trailer home. Jerry was again reluctant to leave his apartment where he had had some happy years with Dora, but he was afraid to disappoint Marjorie. Thus, he sold all of his furniture and gave the money to Marjorie and David and then moved into his new studio apartment at Lawrence House. He was crushed, then, when, after he gave Marjorie the last of his money, she promptly disappeared.

Alone again, Jerry often went to the Levy Senior Citizens Center to socialize, as he had absolutely no one else in his life. At the Levy Center, he met a volunteer, Evelyn Harris, who “had a smile for everyone.” Evelyn befriended Jerry and often went to visit/check on him at his apartment in Lawrence House. The first time she went, she was appalled by the squalor in which Jerry was living. She had suspected something was wrong because his clothes were always dirty and ill-fitting, but when she got to his apartment, she saw that the whole place was dirty, particularly his bed, and that he had no dishes or utensils or food of any kind. Feeling sorry for him, she took him home to live with her. Apparently, it was a happy arrangement, but, again, short-lived, as Jerry then had a heart attack and two strokes.

After his second stroke, the hospital staff where he had been admitted tried to convince Evelyn to place him in a nursing home, but she refused. It didn’t take too long, however, before she realized that she had made a mistake and that caring for Jerry was now too much. With a long-time friend, who also knew Jerry from his days at Lincoln West, Evelyn found and placed Jerry in a nursing home. Only once did Marjorie materialize to visit him, during which time she—as usual—caused havoc between Jerry and Evelyn. Jerry fought with Evelyn, telling her to stay away and not to visit as much, as it was causing Marjorie not to come around. Evelyn was extremely hurt by this and stayed away for a time, until she “came to her senses” and decided to confront Marjorie. Marjorie had long since gone, however, so there was no threat for Evelyn to have to face. Evelyn and Jerry made up, then, and she continued to faithfully visit him.

Things went on this way until 1996, when Evelyn went through routine knee surgery and unexpectedly died. This was very hard on Jerry, though his cognitive status by that point had diminished considerably. With the help of the nursing home staff, he attended Evelyn’s funeral and there met yet another guardian angel, Katie, who was Evelyn’s granddaughter. Katie of course knew about her grandmother’s friend, Jerry, to whom she had devoted so many years, but she had never met him. Before she died, Evelyn had managed to extract a promise from Katie that she would continue to look after Jerry for her. Katie took her promise very seriously and made frequent visits to the nursing home in the city to see Jerry, though she lived forty miles away in Elgin. After a time, Katie asked Jerry if he would consider moving to a nursing home closer to her so that she could see him more, and he eagerly agreed to it, so much so that he became almost obsessed with leaving and pestered the staff constantly to make it happen, which they eventually did.

Once established in the new nursing home, however, Jerry soon soured toward it and begged to be taken back to the nursing home in the city where he had been. Katie gave him some time to get adjusted, but he remained adamant in wanting to return. Finally, then, Katie made the arrangements for him to be transferred back, reminding him repeatedly that she would not be able to visit as often.

Jerry is making a relatively smooth transition back to his former home, though he seems depressed much of the time. His cognitive and physical health continue to decline, and he has begun to repeatedly ask for Marjorie. Katie, for her part, is glad that Jerry is back at his original nursing home, but says that it is difficult when he constantly brings up Marjorie. “She’s a real devil, though Jerry just can’t see it,” she says. She has tried several times to contact Marjorie, at Jerry’s request, but she has failed to ever return Katie’s calls.

(Originally written: January 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Surrounded by Angels…And One Devil appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 3, 2023

She Crossed the Ocean to Find Her Love

Erna Lindner was born on May 27, 1904 on a farm in Austria, which later became part of Czechoslovakia. Her parents, Alban Hager and Sylvia Kainz, worked “night and day” on the farm, and when Alban had to fight in the First World War, the running of the farm fell to Sylvia and her five children: Alban, Jr.; Theresa; Walter; Erna; and Martin. Erna says that it was “a very, very, very had life,” even after her father came back from the war, though, she says, “we always had plenty of good, fresh food.” Erna says that no one really went to school, except Sunday school, and even as young adults, they never went out and socialized, as there was always too much work to do on the farm.

Erna Lindner was born on May 27, 1904 on a farm in Austria, which later became part of Czechoslovakia. Her parents, Alban Hager and Sylvia Kainz, worked “night and day” on the farm, and when Alban had to fight in the First World War, the running of the farm fell to Sylvia and her five children: Alban, Jr.; Theresa; Walter; Erna; and Martin. Erna says that it was “a very, very, very had life,” even after her father came back from the war, though, she says, “we always had plenty of good, fresh food.” Erna says that no one really went to school, except Sunday school, and even as young adults, they never went out and socialized, as there was always too much work to do on the farm.

Erna did meet a boy, however, named Theo Lindner, at church. Her only time to see him was on Sunday afternoons when he would sometimes come to the Hager farm to visit and talk with Erna’s parents. As time went on, all three of Erna’s older siblings left for America. Eventually, Theo left, too. From that point on, Erna was desperate to get to America to be with Theo. Finally, when she was 19, in 1923, her parents arranged for her to travel with a large group of people from their town who were all making the journey together. Only her younger brother, Martin, remained behind to care for the farm and their parents.

Erna stuck with the group on the long ship ride over and then traveled alone to Chicago, where she was reunited with her sister, Theresa. Erna immediately found a job as a waitress at a restaurant at Cicero and 26th and then began looking for Theo. She finally found him, and within three months of arriving in America, she married him. They had a small wedding dinner for immediate family only and went to live with Theresa until they could get someplace of their own. Theo worked as a tailor, and Erna eventually got a job in a factory, where she stayed for 31 years.

Erna and Theo finally got their own place, which was a two-room apartment, and later saved enough to buy a two-story house. During the depression, however, they found they couldn’t pay the mortgage, so they lost the house, which, Erna says, broke Theo’s heart. Erna says they had “a nice life together,” but that Theo never really go over losing the house. In fact, she believes that it contributed to his early death at age fifty in 1950. Apparently, he went to sleep one night and never woke up. They had been together for twenty-seven years and had three children: Sarah, Ruth, and Paul. Theo lived to see both daughters married, but died during Paul’s engagement.

Erna continued working, even after Theo’s death, supporting herself and helping with her grandchildren. She was an extremely hard worker, never taking time for herself or any hobbies, except for dancing. She loved music and continued to go to dance halls until she was seventy-five years old, at which point, she says, her legs “finally gave out.” She never traveled, except for her one-time trip from Austria/Czechoslovakia to Chicago. After that, she says, she “never once stepped foot out of Chicago.”

In her later years, unfortunately, more sadness occurred for Erna. Her daughter, Sarah, became ill, and Erna spent the last fifteen years of Sarah’s life going to hospitals to visit her whenever she had to be admitted and helping her with her children, Vincent and Fanny. Not only was this difficult to deal with over the years, but then Vincent committed suicide, leaving behind two children of his own and a wife, who was eight months pregnant at the time. Erna explains that Vincent died in a car “accident”—that he was in a closed garage and died of “fumes.” She does not equate his death with suicide. Whether she cannot face the truth or was never really told the truth, is unclear. Not long after Vincent’s suicide, Sarah died, too. And shortly after that, Erna’s son-in-law, Ralph, (her daughter, Ruth’s husband) died as well.

Despite all of this loss and tragedy, Erna does not seem bitter or depressed. She often says, “What can we do?” With Sarah deceased and her son, Paul, living in Florida, Erna became more and more dependent on her youngest daughter, Ruth. Since her husband, Ralph’s, death, however, Ruth has been having her own increased health problems, as well as depression, and has found it harder and harder to care for her mother. Eventually, she broached the subject with Erna of going to a nursing home, which Erna was surprisingly accepting of. Erna herself chose the Bohemian Home for the Aged, because she was familiar with it, as she had often attended the Home’s annual Memorial Day picnic, which the community at large was invited to participate in.

Erna has thus made a very smooth transition. “I’m happy with this place. It’s clean,” she says and is very proud of the fact that she has learned her way around the facility so quickly. “I’m not dumb,” she says. “I’m just old. I don’t have anybody, only my daughter, and I wanted to be with people, so I came here. I’ve had a hard life, but you have to take care of yourself. You can’t depend on anyone else to make you happy.”

(Originally written: May 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Crossed the Ocean to Find Her Love appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

July 27, 2023

The Secret to Happiness: “Be Content With What You Have.”

Estelle Oberst was born in Chicago on October 20, 1900. Her father, Edwin Larsen, was an immigrant from Norway, and her mother, Theresa Amsel, was an immigrant from Germany. The two somehow met after they arrived in Chicago and married not long after. Estelle does not remember exactly where her father worked, but she thinks it may have been in a factory. Her mother cared for their eight children (Gunther, Edward, Agnes, Hans, Felix, Helen, Estelle and Ludmilla), all of whom made it to adulthood except one, Ludmilla, who died in the flu epidemic. At age 94, Estelle is the only member of her family still alive.

Estelle Oberst was born in Chicago on October 20, 1900. Her father, Edwin Larsen, was an immigrant from Norway, and her mother, Theresa Amsel, was an immigrant from Germany. The two somehow met after they arrived in Chicago and married not long after. Estelle does not remember exactly where her father worked, but she thinks it may have been in a factory. Her mother cared for their eight children (Gunther, Edward, Agnes, Hans, Felix, Helen, Estelle and Ludmilla), all of whom made it to adulthood except one, Ludmilla, who died in the flu epidemic. At age 94, Estelle is the only member of her family still alive.

Estelle attended two years of high school and then quit to begin working as a punch press operator at Sunbeam. When she was nineteen, a new foreman started at work, Joseph Oberst, who took an immediate liking to Estelle. Estelle was not interested in him, but he continued to pester her until she finally agreed to go on a date with him. She was apparently not impressed, but Joseph continued to pressure her to go out with him, which Estelle would reluctantly do from time to time. Her friends were shocked, then, when one day she announced that she was going to marry him and would not explain why.

As soon as they were married, Joseph demanded that Estelle stay home to be a housewife, which Estelle obediently agreed to. She eventually had two children, Charles and Joseph, Jr., whose birth she almost died during because he was so large. Estelle’s marriage to Joseph was apparently an unhappy one, and she describes Joseph as “a miserable man.” Still, she tried to create a nice home for her two little boys.

Besides caring for her children, Estelle was devoted to her church, First Congregational, and was the oldest living member for many years. She was very active there throughout her entire life and held a variety of volunteer positions, including sitting on the board of many committees. She also ran craft bazaars, organized bake sales, was a leading member of the sewing circle, and cooked and cared for many of the sick and elderly in the parish. In fact, many, many elderly were able to stay in their homes a few extra years because of Estelle. Estelle even took in her mother-in-law, Margaret, though she was a very angry, bitter woman. None of Margaret’s other children wanted anything to do with her, so Estelle offered their home to her and lovingly cared for her until she died.

Estelle spent most of her life devoted to caring for others, but in her seventies, she began experiencing her own series of losses. The first was the death of her son, Joseph, Jr., who died suddenly at age 48 in 1976. He had never married. Then, a year later, her husband, Joseph, died, followed by her other son, Charles, who left behind a wife, Virginia, but no children. So in the span of two years, she lost her husband and both sons – her entire family, except her daughter-in-law. It was a very difficult time for Estelle, but she continued to try to have a positive attitude.

As the years went along, she came to rely more and more on Virginia, who likewise became increasingly devoted to Estelle and very protective of her. Virginia describes Estelle as being “a tough woman with a very strong will to live and a very positive attitude toward life.” Estelle, she says, would do anything for anyone and “has a heart of gold.” Virginia says that Estelle would never go to someone’s house without bringing them something, usually something she baked or sewed. She says she dealt with her many losses in life, including her horrible marriage, by constantly reaching out to others. If she was experiencing something sad, she would seek out someone worse off than herself and try to comfort them.

Estelle was still very active (and drove herself everywhere!) up until the age of eighty-eight when she fell and broke her hip. She was temporarily hospitalized but was eventually able to go back to her own home. She continued to have falls for the next four years and ended up in the hospital again in 1992 after a particularly bad one. Though Virginia has been helping Estelle for several years with cleaning and errands, she recently began to feel that she could no longer care for Estelle full-time, as she herself is in her seventies now with her own health problems, including a bad back. Neither of them could afford the kind of home health care Estelle would need in order to stay in her home, so Virginia made the decision that Estelle should be released from the hospital to a nursing home.

Estelle is not particularly happy about her placement and believes that she will someday return home. She is a very agreeable, sweet person, but is very hard of hearing. This, plus the fact that her attention span and memory are poor, makes it hard for her to participate in activities or befriend other residents. She enjoys one-on-one attention from the staff, however, and will converse as much as she is able. Meanwhile, Virginia tries to visit as often as she can.

When asked about her life, Estelle says that is was a happy one, though she still misses “my boys.” When asked what her secret to happiness is, she attributes much to her faith and likewise says that “you have to be content with what you have. There’s always someone worse off than you who can use a hand.”

(Originally written: May 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Secret to Happiness: “Be Content With What You Have.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

July 20, 2023

“More Like Sisters”

Doris Gockel was born on March 15, 1934 in Chicago. Not much is known of Doris’s early life, except that her mother, Gertrude Molnar, who was of Hungarian descent, had Doris when she was very young. About a year after Doris was born, Gertrude married a man named Walter Sands, who was not Doris’s birthfather, but who came to love Doris as his own child. Gertrude and Walter never had any children together, so Doris was everything to them.

Doris Gockel was born on March 15, 1934 in Chicago. Not much is known of Doris’s early life, except that her mother, Gertrude Molnar, who was of Hungarian descent, had Doris when she was very young. About a year after Doris was born, Gertrude married a man named Walter Sands, who was not Doris’s birthfather, but who came to love Doris as his own child. Gertrude and Walter never had any children together, so Doris was everything to them.

Doris went to school until the tenth grade and then quit to begin working. Over the years she had a variety of jobs, though she says that her job at an ice cream parlor was her favorite. Doris did not go out much, preferring to be at home with Gertrude and Walter, but one night her friends persuaded her to come to the St. Patrick’s Night Ball at the Merry Garden Ballroom. After much urging on the part of her friends, Doris finally agreed to go, since it was very near her birthday, and it was there that she met a boy named Willie Gockel. The two started dating and married very quickly. Doris was just seventeen, and Willie was eighteen. Willie worked as a plasterer, then as a carpenter, and eventually had his own little contracting business, while Doris stayed home and cared for their three children: Linda, Susan and David.

Doris says that “everything was fine in a way” between her and Willie, but after about twenty years together, she says that Willie started “drinking and going out with the guys.” Eventually he “ran away with some woman.” Doris’s son, David, does not know all of the details of went wrong in his parents’ marriage, but he confirms that his father left when David was around twelve years old. Doris had no choice but to find a job, then, and began working as a barmaid at Lakeside Tavern. Doris worked there for over thirteen years and made a lot of friends, many of whom became like a family to her. It was during that time, though, that Doris began to drink a lot, which, says David, was perhaps “just part of the job.”

Despite her drinking and her seedy job at the bar, David says that Doris loved decorating and fixing things up around the house. She had a talent for decorating and had the further talent of being able to do it “on hardly any money at all.” Her favorite thing to do was to go to garage sales with her mother, Gertrude, to find things they could refurbish. They also both shared a love of gardening, particularly of flowers, and could both “make sticks grow.” Doris and his grandmother were very close, David reports. “They were more like sisters than mother and daughter.”

Unfortunately, in the early 1980’s, Doris suffered a brain aneurysm and was hospitalized for a very long period of time. According to David, she nearly died on three occasions, each time having to be revived by the staff. Doris made it through, but it was a long recovery, during which time she had to relearn everything. Eventually Doris was able to go home and live independently, though her vision and equilibrium were not perfect, and, according to David, she has never been the same mentally. She has always been just “a little bit off” since the whole ordeal, prompting David and his wife, Sharon, to get into the habit of checking on her several times a week in order to help her with various tasks.

Doris was able to manage this way for the next ten years or so until the early 1990’s when her daughter, Susan, separated from her alcoholic husband and went to live with Doris to “take care of her.” David and Sharon think that this was the beginning of the end for Doris, as Doris then became subjected to what they have referred to as Susan’s “bad influence.” Ever since the aneurysm, Doris had given up drinking, but when Susan came back to live with her, she started up again. Likewise, David and Sharon believe that Susan, whom they say is also unstable, was probably not providing Doris with balanced meals or regulating her medication correctly. Susan became very protective of Doris during this time and was resentful if David or Sharon still tried to help, claiming that it wasn’t necessary and that they were “interfering.”

Things went from bad to worse when Susan came home one day and found Doris out in the yard, unconscious. It is not known how long she had been laying there, but the doctors concluded that she had had a stroke. When she eventually recovered in the hospital enough to be released, David and Sharon thought it obvious that she should go to a nursing home, but Susan disagreed. David attempted to call his other sister, Linda, to get her involved, but since she had been estranged from the family for a long time, she refused to have any part of the conflict between Susan and David. Therefore, it was David against Susan, and despite David’s protests, Susan was eventually able to persuade the doctors to allow her to take Doris home with her again.

This arrangement, however, tragically only lasted about two months. Two days before Christmas, 1995, Susan dropped Doris off at the emergency room of Swedish Covenant Hospital and took off, apparently reunited with her estranged, alcoholic husband. From that point, David took control and arranged for Doris to be released to a nursing home.

Recently admitted, Doris seems to be adjusting well to her new surroundings, though she is confused much of the time and sometimes believes she is seeing various family members on television as she sits watching it. She is able to converse with other residents, though she seems to have a hard time focusing and has to concentrate to speak. She attends activities, but does not always participate unless helped by a staff member or a volunteer. David tries to visit as often as he can, but he is also burdened with having to manage the care of his grandmother, Gertrude, who is also still alive and in a different nursing home. Doris says that she would rather be home, but she understands that she cannot live alone. “It’s not so bad here,” she says, but she misses being with her family, especially her mother.

(Originally written January 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “More Like Sisters” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

July 13, 2023

The Classic “High-Society” Man

Carl Nilsson was born on January 24, 1937 in Chicago to Nils Nilsson and Brita Lindgren. Not much is known about Carl’s early life or his parents, except for a few facts, namely that they were immigrants from Sweden and that Nils worked as a tool and die maker once he got to Chicago. Carl describes his father as a workaholic. His mother, he says, was primarily a housewife, but worked occasionally as a waitress for the private parties of the Kemper Insurance Company. Carl was their only child.

Carl Nilsson was born on January 24, 1937 in Chicago to Nils Nilsson and Brita Lindgren. Not much is known about Carl’s early life or his parents, except for a few facts, namely that they were immigrants from Sweden and that Nils worked as a tool and die maker once he got to Chicago. Carl describes his father as a workaholic. His mother, he says, was primarily a housewife, but worked occasionally as a waitress for the private parties of the Kemper Insurance Company. Carl was their only child.

Carl attended college for three years and then got a job working in personnel at a paint factory. Over the years, he worked his way up the corporate ladder until he became vice president of the company when he was around forty years old. He was apparently a very fashionable, successful executive who loved to party. He married a woman named Judy Breitbach and had one child with her, Patricia.

As Carl’s career expanded, his lifestyle apparently became more and more lavish. He bought a big house in Park Ridge and filled it with expensive, custom-made furniture. He had “liquid lunches,” big parties, closed the bars down at night, and belonged to the country club. He was the classic “high-society” man and belonged to many different community organizations, such as the Elks and the Moose. He was also a member of a Swedish choral group and sat on the board of directors at the Swedish Museum, among many others institutions.

Carl’s extravagant lifestyle all came crashing down, however, when the company filed for bankruptcy and Carl lost his job. Though he tried for a while to find a comparable position in another company, he wasn’t successful, partly perhaps because he was thrown into a deep depression. He grieved for his lost job and what he saw as his place in society and thus slowly began to withdraw. His participation in his many community organizations dwindled, and his marriage to Judy began to fall apart. He began drinking even more than he had before, until Judy eventually divorced him, taking Patricia and moving to Texas. This was the last crushing blow for Carl.

He eventually had to sell the house and moved into a “trashy” apartment where he further “drank his life away” and developed diabetes. He remained in denial about his diagnosis, however, and eventually had to have one leg amputated. He was working for Carson, Pirie, Scott at the time but eventually lost that job as well when he had to have the other leg amputated, too. Completely handicapped now, he went on full disability, though he continued to make some money “under the table” by occasionally working for a travel agent.

It was after his second amputation that he had to spend some time in a physical rehabilitation center to learn how to care for himself now that he was a double amputee. At the rehab center, Carl had the good fortune of meeting and becoming friends with a man named Steve Hinkel. Steve was a volunteer at the center who often came to give motivational talks and workshops for both patients and doctors based on his own life experience. He himself had been in a serious car accident when he was twenty-eight years old and almost froze to death. He lived through the ordeal, but he lost his hands and feet as a result. His recovery from the accident, however, was amazingly quick, which he still attributes to his positive attitude.

Carl was instantly attracted to Steve’s positivity and became very attached to him. Steve spent many hours talking with Carl while he was in the rehab center and even helped him get settled back into his apartment once he was released. Steve continued to visit and follow up with Carl, who was still abusing his body by eating anything he wanted and consuming large quantities of alcohol. Often Carl would ask Steve to take him out to lunch, where he would proceed to order drinks, though Steve cautioned him otherwise. “Oh, a little nip once in a while won’t hurt me,” Carl would say. If Steve pressed him to stop, however, Carl would argue, “What does it matter? I’m going to die anyway.”

Steve describes Carl’s apartment as “dirty and run-down” and perpetually looking like “it was ready for Halloween with an orphanage next door” in terms of how many cakes and sweets littered it, as well as bottles of liquor and trash. Amongst all the rubbish, however, was a little “shrine” that Carl had erected to his daughter, Patricia. Though his wife had full custody over the years of Patricia, Judy allowed her to spend the summers in Chicago with her father, which Steve guesses was the only thing that kept Carl going for years. Indeed, the only “décor” in the apartment consisted of photographs and clippings of Patricia and her many accomplishments.

At one point, worried about her father, Patricia even transferred to DePaul for her junior year of college so that she could be closer to him. It proved to be too much for her to handle emotionally, however, and she eventually returned to Texas. She still maintained contact with him, however, as the years went on, calling him weekly and occasionally coming up to visit. Patricia is married now and still living in Texas, but she has flown up several times during Carl’s various hospitalizations. She has also been able to meet Steve and has thanked him for helping her dad and for keeping her updated on his situation.

Carl’s condition worsened recently when he began experiencing “weird spells” and was again hospitalized with heart and lung problems. He was also diagnosed with kidney failure and potentially prostate cancer, though it was inoperable because of his bad heart. At the hospital, he was counseled about changing his bad habits, but he threw many tantrums in which he demanded milk and cheese to be given to him, claiming that they were the “proper food for a Swede.” After this extended stint in the hospital, Carl was eventually allowed to go home with the help of home health care, but it only lasted a couple of months before he ended up in the hospital again. This time, Steve, with Patricia’s long-distance help, was able to help get him admitted to a nursing home.

Carl’s physical health has stabilized since his admission to the home, but he is very confused and distraught and is not adjusting well. He seems to have lost the will to live and remains belligerent and temperamental. He fights with the staff when they attempt to get him out of bed, saying that it is “cruel,” and that “you’re all the same!” or “no one cares!” Similarly, he continues to throw tantrums in which he demands milk and cheese three times a day, against the dietitian’s advice.

Besides these loud outbursts, he otherwise remains despondent and depressed most of the time, even when Steve comes to visit. It is very difficult to have a conversation with him as he frequently “drifts off” mid-sentence and never gets back to his original thought, even when prompted. He continues to ask for Patricia and begs to be allowed to die. Steve continues to visit, despite his own handicaps, and tries to encourage him to participate in the life of the home for the time he has left.

(Originally written: January 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Classic “High-Society” Man appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.