Michelle Cox's Blog, page 6

July 6, 2023

“My Angel”

Theresa Svoboda was born on March 23, 1911 in Chicago to Frank and Simona Svoboda, both of whom were immigrants from Czechoslovakia. According to Theresa, her father came alone to the United States looking for work and found a job right away, which he considered lucky, as jobs were scarce. He began working as a sort of blacksmith and did ornamental work with iron. He made beautiful and intricately-detailed iron fences. Having gotten a job, he immediately sent for Simona to join him. Together they had two children, Theresa and Bernard.

Theresa Svoboda was born on March 23, 1911 in Chicago to Frank and Simona Svoboda, both of whom were immigrants from Czechoslovakia. According to Theresa, her father came alone to the United States looking for work and found a job right away, which he considered lucky, as jobs were scarce. He began working as a sort of blacksmith and did ornamental work with iron. He made beautiful and intricately-detailed iron fences. Having gotten a job, he immediately sent for Simona to join him. Together they had two children, Theresa and Bernard.

Theresa went to school through the eighth grade and attended one year of high school before she quit. She claims that there was “too much fooling around,” so she enrolled in a business college instead. When she graduated, she began working in an office and stayed there for eleven and a half years. After that she moved from office to office over the years and says that she enjoyed all of her jobs.

Theresa never married. She says that she had some nice boyfriends, but none of them stood out as being really special. Nor did she want to get married just to be married. Besides that, she didn’t want to leave her parents “in the lurch,” especially because the economy was so bad. She felt that it was her duty, since she had a good job in an office, to stay and help support them. Theresa lived with her parents in their two-flat on Christina Avenue until 1955, when her parents both died within six weeks of each other. Her father died of a “bad toe.” Apparently it got infected somehow and turned “dark as a plum,” and he eventually died. Simona died six weeks later, though Theresa is not sure of what. Five years after that, her brother Bernard died as well.

Not much else of Theresa Svoboda is known. What happened from that moment in 1960 when her brother died to her present admission to a nursing home is not entirely clear. Apparently, she continued to live in the two-flat on her own, but as the neighborhood got worse and worse, Theresa became more and more reclusive. She was robbed at least twice, and the first floor apartment was left empty and was eventually gutted, presumably by neighborhood gangs.

About five years ago, in 1989, Theresa suffered from frost-bite and had to have several toes amputated as a result. The story made the newspaper, and after reading the article about Theresa’s plight, a woman by the name of Sissie Novak decided to take action. She began a correspondence with Theresa and sent her many packages with clothes, blankets, food, and personal items.

Recently, however, Sissie stopped receiving return letters from Theresa, which worried her. Theresa was not in the habit of writing often to Sissie, but she would at least send a thank you note after receiving a package. When the notes stopped coming, Sissie sent a postcard, urging Theresa to respond to let her know she was okay, as Sissie had no other way of contacting Theresa, who did not own a telephone. When she still did not hear from Theresa, Sissie finally decided to call the police. The police eventually followed up on the call, but Theresa refused to open the door, fearing a trick. The police then urged her to go to the window and look out, where she could see their squad car, uniforms and badges. Reluctantly, then, she opened the door.

Upon entering her apartment, the police discovered that she was living there with no heat and no utilities and that her only source of food was apparently a nearby McDonalds. Her legs were severely frost bit, and she could barely walk. The officers attempted to get her to leave with them, but she refused. They left and reported their findings to Sissie, who, because of her own health issues, could not drive into the city to aid Theresa herself. Sissie continued to repeatedly call the police, begging them to periodically go and check on Theresa. Finally, one officer took it upon himself to try to help Theresa. He went back to the apartment on his own time and managed to coax her out and then drove her to Methodist Hospital, where she eventually had to have both legs removed.

Meanwhile, Sissie stayed in contact with the hospital and when it was time for Theresa to be discharged to a nursing home, she urged the staff to place her in a Czech home where she hoped Theresa would get not only a warm bed and good food, but a fellow community she might be able to relate to.

As soon as Sissie was physically able to drive to the city, she met up with the officer who had taken Theresa to the hospital, and the two of them went to the two-flat to see if there was anything salvageable or anything Theresa might want or need at the nursing home. When Sissie arrived there, it was worse than she had ever imagined. It was filthy, wretched and freezing. Gang graffiti covered the inside walls, and it appeared to be little more than a wind break from the elements. But what surprised Sissie the most, however, was that all of the packages she had sent over the years with food, blankets, clothing —even a space heater—were stacked up in the corner, unopened.

As for Theresa, she says she is “content” with her current placement in the nursing home, though she seems muted and depressed. Nothing seems to bring her either joy or sadness. She expresses no concern or worry about anything at all, to the point of complete indifference. She doesn’t believe in planning ahead, she says, “because you never know what’s going to happen.”

Sissie visits whenever she can, though she lives in the far suburbs, so it is a bit of a trek for her. She says that she was angry when she discovered that Theresa had not used a single thing she had sent to her, but, upon learning Theresa’s history, she eventually came to the conclusion that the relatively sudden deaths of all of Theresa’s family members “must have drove her a little crazy.” Likewise, Sissie says she thought Theresa would be more grateful to her for rescuing her, but Theresa does not seem to understand that it was Sissie who was responsible for getting the police to intervene. Theresa does, however, seem to realize that it was Sissie who sent her all the packages and calls her “my angel,” whenever she visits.

(Originally written February 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “My Angel” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

June 29, 2023

“Winnie Didn’t Lead That Kind of Life…”

Loretta Coleman was born on April 22, 1936 in Louisiana to Frank Harris and Ruth Roberts. Not much is known about Loretta’s parents, but she says that she and her three siblings had a good childhood and that they were raised in a very strict Baptist household. Loretta graduated from high school and was then sent to live with relatives in Chicago, where she got a job as a cook in a cafeteria.

Loretta Coleman was born on April 22, 1936 in Louisiana to Frank Harris and Ruth Roberts. Not much is known about Loretta’s parents, but she says that she and her three siblings had a good childhood and that they were raised in a very strict Baptist household. Loretta graduated from high school and was then sent to live with relatives in Chicago, where she got a job as a cook in a cafeteria.

At some point, Loretta was introduced to Roy Coleman, who worked at a meat packing house. They began dating and eventually married. Once she got pregnant with their first child, Leroy, Loretta quit her job at the cafeteria and stayed at home to take care of him. She and Roy had a total of seven children (Leroy, Charles, LaVergne, Franklin, Mattie, Abraham, and Winnie). Loretta says that she and Roy were very close in the early days of their marriage but that as time went on, they drifted apart, especially when he started to stay out late, going to bars and picking up other women. Eventually, they divorced, and Loretta was forced to go back to work as a cook, leaving the children to fend for themselves while she was gone.

While that period in her life was difficult to get through, her biggest tragedy was when her youngest daughter, Winnie, was murdered at age twenty-four. Loretta says that Winnie had had a baby, Marcus, out of wedlock but was estranged from the father, Dean Richards. Winnie apparently led a simple life at home with Loretta, which makes her death all the harder for Loretta to accept, because, she says, “Winnie didn’t lead that kind of life.” Loretta describes Winnie as a quiet, good girl who worked two jobs to support herself and Marcus and who sang in their church choir. She was “a very good person,” Mattie says, and she still cries about Winnie’s death, which occurred just two years ago.

When asked what happened to Winnie, Mattie relates that for some reason, Winnie agreed to meet up with Dean one night and left Marcus, then just one year old, with Loretta for the evening. When Winnie didn’t come home, Loretta called the police, who later found Winnie’s body in a hotel room, where she had been shot to death. The police eventually picked up Dean and held him for a time, but they did not have enough evidence to convict him. In Loretta’s mind, however, he is guilty of murdering her Winnie.

Following Winnie’s death, the care of Marcus fell to Loretta. Though she loved him completely, she did not think she could raise another child, especially with her own health issues, so she decided to give Marcus to her younger sister, Agnes, who was living in California. Loretta says that it almost killed her to give up Marcus, since he was a part of Winnie, but she knew she couldn’t give him what he needed and that it was for the best. After he was gone, Loretta then went through a grieving period for both Winnie and Marcus. She often describes how during those many months, she would wake up happy each day, but then would remember the tragedy all over again and be thrown into a fresh depression and despair. To make matters worse, Loretta’s son, Franklin, who was also living with her at the time of Winnie’s death, began drinking heavily as a way to deal with his grief over his sister’s death and quickly became an alcoholic.

Loretta eventually sought the professional help of a counselor, whom, she says, helped her immensely, as did prayer. She continues to urge Franklin—and all of her other children—to seek help, as well, to aid them in coming to terms with Winnie’s violent death, but she has had varying degrees of success in getting any of them to go.

Loretta says she takes one day at a time. She attempts to go on as best she can and tries to keep Winnie alive by remembering the funny things she did and the good times they had together. She also tries as hard as she can to keep in touch with her grandson, Marcus, so that he will remember his family in Chicago, but it is difficult. Tending to her many plants, decorating, and going to bingo and coffee shops are all things that have helped her to cope these last two years.

Recently, however, Loretta has had to have her toes on her right foot amputated and was thus admitted to a nursing home to recover. Franklin and her daughter, Mattie, visit her frequently. Both are anxious for their mother to come home. Loretta does not open up easily and seems reluctant to share all of her story. She is a very private person and does not interact much with the other residents, who are all significantly older than she. She spends her day doing crossword puzzles, reading the Bible, talking on the phone or watching TV, biding her time until she can return to her home. She is a calm, patient woman, who will answer questions politely, but she tends to direct every conversation back to the topic of her murdered daughter. “Why did this have to happen?” she often asks. “What is the point of it all?”

(Originally written March 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Winnie Didn’t Lead That Kind of Life…” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

June 22, 2023

The Ultimate Romantic

Jan Beranek was born on December 21, 1909 in Slovakia to Kornel Beranek and Hedvika Klimy. Jan’s father, Kornel, worked as a very successful tailor. He had large accounts and employed six to eight men at any given time. When the WWI broke out, however, Kornel was forced to dissolve his tailor shop to become a soldier. He wasn’t away at the war for long, though, before he became deathly ill and was discharged home. Kornel spent a long time recovering and then began a concrete company, which was even more successful than the tailoring business. In total, he employed fifteen to twenty men, and the Beraneks were considered fairly well-off.

Jan Beranek was born on December 21, 1909 in Slovakia to Kornel Beranek and Hedvika Klimy. Jan’s father, Kornel, worked as a very successful tailor. He had large accounts and employed six to eight men at any given time. When the WWI broke out, however, Kornel was forced to dissolve his tailor shop to become a soldier. He wasn’t away at the war for long, though, before he became deathly ill and was discharged home. Kornel spent a long time recovering and then began a concrete company, which was even more successful than the tailoring business. In total, he employed fifteen to twenty men, and the Beraneks were considered fairly well-off.

Jan’s mother, Hedvika, stayed at home with their six children. She was apparently very intelligent and had been partially educated. Her two brothers had studied to become teachers, and Hedvika was just a year into her studies to become a teacher as well when her father died. Hedvika had no choice, then, but to quit so that she could help her mother with her four younger sisters.

Education remained very important to Hedvika, however, as it was with Kornel, so all of their six children were sent to school beyond the grammar school level. All three of Jan’s sisters went to high school and three years of “industrial school,” where they studied “domestic science.” Jan went to high school and then to four years at a business academy to study accounting. In the middle of his training, though, when Jan was just sixteen, Kornel died. Jan says that his father’s death had a profound effect on him and that he still remembers him with great fondness.

Jan’s first job out of school was working as a bookkeeper for a man whose business was to “buy and sell goods.” Jan was so efficient that after only a couple of months, the man ran out of work for him to do and thus laid him off. From there, Jan’s brother-in-law, an engineer, got him a job in a building company, where Jan worked as a timekeeper, a bookkeeper and an assistant surveyor for over eight years.

It was during this time that Jan met the love of his life. He was twenty-five years old.

He tells the story as follows: On a warm April day in 1935, he got the urge to be outdoors instead of in his stuffy office. He snuck away from his desk at lunch time and decided to go walking in the fields. Unable to resist, he laid down in the fresh grass for a quick nap and soon fell into a deep sleep. He didn’t wake up until 1:30 p.m.—well past his lunch hour. He immediately jumped up and rushed back to work. Luckily, he was not get in trouble, but he developed a terrible cold from lying so long on the damp ground. The cold persisted for several weeks, so he finally asked permission to leave work to go to a doctor and, upon getting his boss’s approval, took the streetcar into town.

At the doctor’s office, there were about five people waiting ahead of him. As Jan took his place in line, he saw before him a lovely young girl, idly twirling a French hat. When she dropped it, Jan bent over and picked it up and handed it back to her. From there they began talking, and Jan learned that her name was Amalie Laska and that she lived with her uncle, a retired train officer, in town.

Finally Amalie was called in to see the doctor, was examined, and then left, waving goodbye to Jan as she went. Jan then raced into the doctor’s office and began to ask him for any information on Amalie. As it happened, Amalie’s brother and the doctor had gone to school together and were very good friends, so he knew all about Amalie. He didn’t think it right, however, to give Jan her address.

When Jan finally left the doctor’s office, wondering how he could see Amalie again, he found to his surprise that she was standing in the vestibule of the building, trying to avoid the rain that was pouring down. Jan was delighted to see her, but she turned and reproached him, saying, “Don’t think I waited here for you!”

Rather than be deterred by her comment, however, Jan thought she was even more delightful than he did before. He offered to help her onto the streetcar, but she vehemently declined, saying that she did not have the money for the streetcar, and likewise refused to let him pay for her. Thinking quickly, Jan left her for a moment and rushed out into the rain to a nearby shop and bought her a box of chocolates.

When he arrived back in the vestibule, soaked, and handed her the chocolates, she seemed angry at first but then politely accepted them. The rain let up, then, and they parted, Amalie refusing any help from him. Sadly, he caught the streetcar back to work, and Amalie walked home, where she hid the chocolates under her pillow so that her uncle, who was extremely strict, wouldn’t see them.

Jan was utterly surprised, then, when upon walking home from his streetcar stop, he happened to look up at a house he was passing and saw Amalie in the window! It was a house very near his sister and brother-in-law’s home, where he was currently living. He couldn’t believe his good fortune! He waved, and to his delight, she waved back.

Because Amalie’s uncle did not approve of her dating anyone at all, she and Jan developed an elaborate set of hand signals to give to each other while he stood in the street beneath her window. This went on for many weeks until one day when Amalie’s uncle happened to notice Jan in the street making strange hand gestures. Amalie’s uncle feared Jan was an insane lunatic and that he was perhaps attempting to intimidate the elderly neighbor woman who lived above them. Upon closer inspection, however, he realized he was gesturing to Amalie and was furious!

That was the end of Jan and Amalie’s secret relationship. Jan was hauled into the house and properly introduced and, to the uncle’s surprise and pleasure, then accompanied them to church! As time went on, Amalie’s uncle’s stiff exterior began to melt a little, and he eventually grew to like and approve of Jan.

Jan proposed to Amalie on a Sunday—July 10th, 1935, which happened to be her name-day. They took the streetcar out into the country for a picnic. Jan brought flowers and chocolates, and they sat by a creek and had a picnic lunch. Jan then asked her to marry him. She accepted, but she cried because she had nothing to offer him. Jan, needless to say, did not care, so overjoyed was he that she was to be his wife.

They were married on April 4, 1936 at 4:00 pm. At first, Amalie’s uncle was not crazy about them marrying so young, but when the couple assured him that he could live with them, he rapidly gave his approval. At the last minute, however, he changed his mind and went to live with his sister instead.

Soon after their marriage, Jan decided that he wasn’t being promoted fast enough in the building department where he worked, so they decided to move to Prague, where he got a job with the city sewer department as a surveyor. While there, a friend asked him if he wanted to work part-time for the city newspaper. Jan agreed and soon liked it so much that he began working there full time. He advanced quickly and was soon the administrator of the whole newspaper by 1945.

Meanwhile, Amalie found work as a seamstress until their daughter Klara was born on August 15, 1939. Jan simply adored his baby daughter. He took her for walks in her buggy every Saturday, and the three of them were very happy. When she was only five years old, however, Klara came down with diphtheria and died. For Jan, it was the most tragic thing that had ever happened, or ever would happen, to him in his life. Unfortunately, he and Amalie did not have any more children, as the doctor warned them that it would put Amalie in mortal danger. Also, they were unwilling to bring another child into the world when their lives were so uncertain due to the WWII and the political unrest around them.

Somehow, Jan and Amalie survived their personal tragedy and the war years as well, but in 1948, Stalin began rounding up all of the intellectuals and leading men of the country. Jan, as head of a major newspaper, was targeted, so Jan and Amalie decided to flee. They made their way to an international refugee camp in Germany, where they stayed three months. From there, they were transferred to a camp in Italy for a year and a half. They wanted desperately to immigrate to America, but the waiting list was over two years. Meanwhile, the conditions in the camp were terrible, and Amalie was sick. They decided, then, to go to Australia instead.

A friend they had met in the camp went with them, and once in Australia, Jan found a job with the government, laying electrical lines. Amalie was able to again find work as a seamstress. When Jan’s two-year contract was up for that particular job, they moved to Malvern, where Jan worked for an English factory that made jam. While there, Jan met a man named Mr. Gregory, who befriended him and invited him to see the observatory where he worked.

The Americans had built an observatory near Malvern, where periscopes for submarines, among other things, were built. The observatory also contained a 30-meter telescope, which was under the strict control of Greenwich, England. It was in a very secluded place in a forest on a hill, and Jan was fascinated by the work that went on there. He spent a lot of his extra time at the observatory and even volunteered some of his surveying skills when needed.

Eventually he managed to persuade Mr. Gregory to let him look through the telescope, which was off limits to all personnel. So one night, the two men snuck back to the observatory, unlocked the telescope and beheld the night sky. Jan was in awe. For him, it remains the most beautiful sight he has ever seen.

As a whole, however, Jan and Amalie did not like Australia, so in 1956, they left for Canada. They stayed there only a year and a half, however, as Jan could not find work. They were living only on what Amalie could make as a seamstress, so they decided to go back to Australia. When they got there, however, they found that things had changed a lot in their short absence, or so it seemed to them. Unemployment was high, and they found it difficult to make ends meet.

So, once again they decided to leave. It was 1960, and they were finally accepted into the United States. They made their way to Chicago, and Jan got a job in a corrugated paper company, where he remained for fifteen years. Amalie got a job in tailoring at Sears and Roebuck. They bought a home in Chicago, where they lived for fourteen years before selling it and moving to Cicero. They remained in Cicero for their last twenty years together.

In 1990, Amalie died of cancer. Jan has not yet recovered from this blow. After Amalie’s death, a Mrs. Martinek, a friend of Amalie’s for over thirty years, took Jan in to live with her. Jan became terribly depressed, however, and in 1993 tried to kill himself. Mrs. Martinek found him in time, however, and brought him to the hospital. From there he has been discharged to a nursing home for Czechs and Slovaks, where it is hoped he will make a smooth transition.

Though Jan is a talkative, pleasant, well-mannered, well-groomed, lovely gentleman, he seems inherently sad and harbors a lot of anger, which seems to currently be directed toward Mrs. Martinek, whom, he says, “tricked him” into coming to the nursing home. And though he does not say it, perhaps he is angry that she foiled his attempt at suicide. He needs little in the way of medical care, but his depression lingers. Even if he were to improve, he has no home to go to. He has yet to make any new relationships with his fellow residents and instead spends most of the day sitting near the nurses’ station, talking to the staff any chance that he gets about the long, amazing life he has led.

(Originally written: December 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Ultimate Romantic appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

June 15, 2023

She Was Crowned Western Electric’s “Beauty Queen” for 1929!

Vera Kadlec was born on August 10, 1909 in the village of Orlov, which is situated between Pilsen and Prague in what is now the Czech Republic. Vera’s father, Andel Blaha, was the mayor of Orlov, and her mother, Vlasta Doubek, cared for their six children, of whom Vera was the oldest. Vera attended grammar school and then quit to help her mother at home.

Vera Kadlec was born on August 10, 1909 in the village of Orlov, which is situated between Pilsen and Prague in what is now the Czech Republic. Vera’s father, Andel Blaha, was the mayor of Orlov, and her mother, Vlasta Doubek, cared for their six children, of whom Vera was the oldest. Vera attended grammar school and then quit to help her mother at home.

When Vera was around fourteen years old, there was a terrible fire in Orlov, and the Blaha’s home burned to the ground. Almost everything they owned was lost. Having to start all over, they decided they would start over in America. Andel repaired the burnt shell of their home as best he could so that Vlasta and the children could still inhabit it while he took Vera with him to America to get things arranged for the rest of them to follow.

Upon arriving in New York, Andel made his way to Chicago, where an aunt and uncle lived at St. Louis and 28th. Andel found a job right away making furniture, and Vera got a job at Western Electric. After two years of working and saving, they sent for the rest of the family. Vera and Andel picked out an apartment near Komensky Avenue and 30th in Lawndale and bought second-hand furniture to decorate it. By the time Vlasta and the rest of the children arrived, it was finished, and they were all very proud of it.

Vera continued working at Western Electric and eventually met Dusan Holub at a dance in Pilsen Park. Dusan was the son of Czech immigrants, but had been born in Vienna. He worked as a meat salesman for several companies, including Oscar Meyer later in life. Dusan lost no time in proposing to Vera, and they were married shortly after when Vera was just seventeen. They got an apartment at Lawndale and Crawford Ave., and Vera soon had a son, Dusan, Jr.

After only a couple of years, however, Dusan and Vera’s relationship soured due to Dusan’s excessive drinking, and Vera became very unhappy. One day when she was getting her hair done, she confided to her hair dresser, Marie, that she wanted to divorce Dusan but that she couldn’t because she had no money. Marie told her not to worry, that she would give her a job at the beauty shop.

Vera, it seemed, had beautiful skin and hair and had even been crowned the “beauty queen” at Western Electric in 1929. Marie rightly figured that Vera could easily sell beauty products to her customers, which is indeed what she did. Marie’s clients were always commenting on Vera’s beauty and consequently would inquire as to which beauty products she used, making it easy to sell to them. Over time, Vera also learned how to cut and style hair and to give permanent waves and thoroughly enjoyed her new career.

A couple of years after her divorce, Vera met Stephen Kadlec who was a soda pop distributor and then a beer distributor after prohibition ended. They married sometime in the early 1930’s, and Stephen adopted Dusan, Jr., who was about four or five at the time. After their marriage, Stephen did not want Vera to work outside the home, so she gave up her job in Marie’s shop, but she continued to do hair for family and friends. Stephen and Vera had a child, Stephen, Jr. not long after they were married. Theirs was apparently a good marriage, and Vera was a very social, happy woman. She loved talking with neighbors and friends and was an active member of the Ladies Aid at her church as well as Sokol and other Czech clubs.

In 1976, however, her husband, Stephen, died suddenly of kidney and heart failure. For a while Marie then lived alone in their home in Berwyn until her son, Stephen Jr. came back to live with her. He suffered from depression and anxiety and eventually committed suicide. Vera does not seem to have fully accepted this and still speaks of him as if he were alive.

In recent years, Vera has been relying more and more on Dusan, Jr., who began calling Vera every day to make sure she took her medication. Her confusion, however, has recently gotten worse, and she has had a series of falls. Dusan finally made the decision after her last fall to admit her to a nursing home, as he says he cannot possibly continue to care for her remotely, nor can he take her into his home. He is already overwhelmed with caring for his wife, who has recently been diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s; a sick uncle; and his birthfather, Dusan Holub, with whom he has had limited contact with on and off over the years and who is also now in a nursing home. Even with all of these people depending on him, however, he still makes a valiant effort to visit Vera as often as she can.

Vera is delighted to see Dusan when he arrives at the Home, but she is sad and upset when he does not take her home with him, which almost makes the situation worse. She is confused much of the time, though she is a lovely, sweet woman. She is frequently apprehensive and continually stops staff members, and sometimes even other residents, to say: “I’m lost. Can you help me?” Her favorite activities are listening to Big Band hour and bingo.

(Originally written: November 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Was Crowned Western Electric’s “Beauty Queen” for 1929! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

June 8, 2023

He Ran the Farm When He Was Only 12!

Joseph Wagner was born on July 6, 1912 in Lake Zurich, Illinois to Eckhart Wagner and Klara Schwartz, both of whom were born in Germany. As a teenager, Eckhart came over with his father, Otto, and they bought a dairy farm together near Lake Zurich. They sold milk and eggs in town, and at the end of the year, any extra spending money from the sale of the eggs was used for Christmas gifts. At some point, Eckhart was introduced to Klara Schwartz, and they married not long after. They had five children: four girls and one boy, Joseph. Two of the girls, Rita and Elizabeth, died in childhood, and the other two, Marta and Hannah, died of cancer in their fifties.

Joseph Wagner was born on July 6, 1912 in Lake Zurich, Illinois to Eckhart Wagner and Klara Schwartz, both of whom were born in Germany. As a teenager, Eckhart came over with his father, Otto, and they bought a dairy farm together near Lake Zurich. They sold milk and eggs in town, and at the end of the year, any extra spending money from the sale of the eggs was used for Christmas gifts. At some point, Eckhart was introduced to Klara Schwartz, and they married not long after. They had five children: four girls and one boy, Joseph. Two of the girls, Rita and Elizabeth, died in childhood, and the other two, Marta and Hannah, died of cancer in their fifties.

As a young boy, Joseph nearly died as well. Apparently when he was seven or eight, he had a problem with his kidneys. The doctors advised him to refrain from eating meat for one year, though they didn’t really expect him to live that long. Somehow, Joseph was cured of whatever ailed him, however, and grew up strong and healthy. He attempted to attend school over the years, but was always being pulled out to work on the farm by his father and his grandfather, Otto.

When Joseph was twelve years old, his grandfather died, leaving the vast farm solely to Eckhart. As much as Eckhart had tried over the years to be a good farmer like his father, however, it was not a life he enjoyed, nor was it one to which he was particularly suited. Unfortunately, not long after Otto’s death, Eckhart fell very ill himself for an extended period of time with some unknown condition , so the running of the farm fell to Joseph, who seemed to take after his grandfather in his enjoyment and skill at farm work.

Thus at only twelve years of age, Joseph took on the responsibility of paying the bills, getting the milk to town, driving trucks, and scheduling the many farm hands in the family’s employ to do all of the chores and duties around the farm. He was very successful in his endeavor, and his mother, Klara, was very proud of him. Eventually, however, after about a year, Eckhart got well enough to take back the reins, but he squandered everything that Joseph had built. Over time, Eckhart became an alcoholic and subsequently began to make many bad investments, so that by the time Joseph was seventeen, his father had lost the farm entirely. All of their money, as well as their vast property, evaporated in an instant.

Marta and Hannah were already married and gone at this point, so Joseph and his parents were forced out of necessity to find a place to live in town. Joseph found work as a hired hand on other farms, but when the war broke out, he found work in factories. He didn’t like being cooped up inside, however, so he then got a job lifting mail bags on and off railroad cars. It was at about this time that he was introduced through a friend to Mildred Uthe, the youngest of thirteen children. The two fell in love and married and moved to a farm in Northbrook, Illinois, where they lived with the couple who had introduced them. Joseph continued working for the railroad, but he also helped out around the farm for extra money. Joseph and Mildred’s first child, Irene, was born in that farmhouse a year later, in 1944. Shortly after that, the young family moved to Hutchinson St. in Chicago, where they lived their whole married life.

Joseph worked for the railroad for over 30 years and was apparently a workaholic. The family never took a vacation because Joseph never wanted to be away from work for long. Sometimes they got free railroad tickets, so they would go on little weekend trips, but nothing more. If he did have free time, Joseph liked to garden and to read. He had an amazing memory and could recall anything, no matter how detailed.

Mildred, meanwhile, cared for Irene and then Alice when she came along in 1949. Alice was born with club feet and had to wear casts on her legs for a year, which was apparently very worrisome to Joseph. Later, when she started school, she was labeled “mildly retarded,” which utterly crushed Joseph. He could not accept that his child was “abnormal” and thus rejected her. From that point on, Mildred and Irene had to completely care for Alice on their own. Likewise, Joseph refused to have any social interactions and forbade Mildred from ever having friends or family over because he was so ashamed of Alice.

Joseph had been raised in a very strict evangelical Lutheran synod, which did not approve of dancing, drinking or card-playing. These were beliefs that Joseph adhered to all his life, though he fell away from the church and scorned any organized religion. Mildred, however, was Catholic, and she insisted on raising both Irene and Alice in the Catholic Church, though Joseph would not allow them to be a part of any formal Catholic instruction. As adults, however, Irene took matters into her own hands and began the process of joining the Church and also took Alice with her. After they were both accepted into the Church, Joseph apparently relented a bit and finally agreed to at least have his marriage to Mildred blessed.

Joseph continued working until he was forced to retire from the railroad in 1981, when he turned sixty-eight. He couldn’t handle all of the idle time, however, and slipped into a deep depression. Eventually Mildred and Irene took him to a hospital, where he was admitted for two weeks and given electric shock treatments. When he was released to come home, he seemed to have forgotten everything, so Mildred and the girls had to teach him how to do everything all over again. He remained in a “zombie-like” state for over a year before he began to come out of it.

In 1983, Mildred was diagnosed with leukemia, and again, Joseph couldn’t accept this reality. He refused to believe that she was ill and never once went to the hospital to see her. On May 10, 1985, Mildred died at home with Irene tending her. Joseph refused to believe that she was dead for about six months, constantly asking for her. This was particularly painful for Irene, who then had to relive her mother’s death all over again each time she had to explain it to Joseph.

Joseph, Irene, and Alice continued living in the same house on Pensacola until the mid-1990’s when Joseph’s health began to decline severely. He became too weak to walk or to even get out of bed. Also, his mood swings and outbursts were increasing, so Irene finally took him to a hospital, where he was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s and dementia. From there, Irene arranged for him to go to a nursing home, though it was with much guilt and a heavy heart.

Irene visits her father as often as she can, which is difficult considering the fact that she still has Alice at home to care for. The sight of Alice seems to rile Joseph, so Irene tries to leave her at home in the care of a neighbor when she goes to visit her father. Joseph remains very confused and disoriented. He has not made any relationships with the other residents and seems to get the most enjoyment from reading the paper or watching baseball on TV. Only once in a while does he still ask for Mildred.

(Originally written: September 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

SHOWING 10 COMMENTSThe post He Ran the Farm When He Was Only 12! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

June 1, 2023

They Met in October and Married in February!

Emilia Mundt was born on October 26, 1913 in Chicago to Jan Jelen and Zofia Nedved, both of whom were immigrants from Slovakia. Jan came to America with a relative when he was nineteen, and Zofia came with her father when she was fifteen. Somehow Jan and Zofia met and married when Zofia was just sixteen. They had two children very close in age: Bartholomew and Emilia, and twelve years later, they had another girl, Denisa. Zofia stayed home and cared for them in their apartment at Diversey and Ashland, and Jan worked as a maintenance man.

Emilia Mundt was born on October 26, 1913 in Chicago to Jan Jelen and Zofia Nedved, both of whom were immigrants from Slovakia. Jan came to America with a relative when he was nineteen, and Zofia came with her father when she was fifteen. Somehow Jan and Zofia met and married when Zofia was just sixteen. They had two children very close in age: Bartholomew and Emilia, and twelve years later, they had another girl, Denisa. Zofia stayed home and cared for them in their apartment at Diversey and Ashland, and Jan worked as a maintenance man.

Emilia attended school until eighth grade, at which point Jan said “that’s enough.” Emilia lied about her age, then, and got a job doing factory work at Stewart-Warner, a company that manufactured speedometers and other auto parts. She stayed there for two years before leaving to work at a toy factory, but eventually returned to Stewart-Warner.

In 1941, when Jan was 53 years old, the family decided to take a trip to Michigan to visit Jan’s brother, Imrich, and his family. Imrich was eager to show Jan his new car and took him out for a ride on some country roads. Tragically, Imrich apparently lost control of the car on a curve and collided with an oncoming milk truck, causing the car to roll several times. Jan broke his back in three places and ruptured his spleen and died in the ambulance on the way to the hospital. Imrich walked away without a scratch. From that point on, the two families never spoke again, and Imrich did not even attend the funeral. Zofia eventually remarried, but only Denisa was still living at home at the time.

When Emilia was twenty-nine, she attended a cousin’s wedding and was introduced to the brides’ brother, Woodrow Mundt. Woodrow was a third generation German and worked as a bank clerk. A few days after the wedding, Woodrow asked Emilia if she would ever consider going on a date with him. Emilia said yes, and the two of them went out for the first time on October 3, 1942. On December 18 of that year, Woodrow proposed and on February 27, 1943, they were married. “You would never know it,” Emilia says, “but Woodrow was quite a romantic.” Though she had been on other dates before, no one ever stood out as that special until she met Woodrow. He thoroughly charmed her, and she fell in love with him right away.

One thing that Woodrow did not tell her, however, until they had been on several dates together was that he had been married before and had an eight-year-old son, Theodore. Emilia says she was surprised, but in the end, she decided she didn’t mind. She was head-over-heels for Woodrow. When they married, Emilia quit her job at Stewart-Warner to stay home and take care of Theodore. She and Theodore bonded right away, and the two she became very close. Three years later, she and Woodrow had another baby, Virginia.

Emilia and Woodrow apparently had a very happy marriage. Woodrow was eventually promoted and became a supervisor, working at the same bank for over 40 years. They moved a few times over the years, eventually buying a house at Foster and Nagle, where they lived for 33 years. Woodrow and Emilia had very similar tastes. They enjoyed going to the opera and the theater and often had friends over for cards, though they weren’t a “drinking, dancing sort of group,” says Emilia.

Once Virginia was in school, Emilia went back to work part-time at an insurance company. She loved reading and crosswords, and was a very active member of St. Cornelius parish. She raised Virginia Catholic, though Woodrow and Theodore were Lutheran. Eventually, however, Theodore converted to Catholicism in order to marry his girlfriend, Janice. Virginia eventually married, too, and moved to Phoenix, Arizona, though she and her husband have no children.

In 1973, Woodrow had a mild heart attack and took early retirement at age 63. He was physically weakened, however, and needed a lot of help. As the years went on, Emilia was less and less able to assist him as her own health began to decline. Eventually, they hired a nurse to come in for four hours a day, five days a week. Theodore and Janice would then fill in the gaps on the weekends to make sure they were okay.

In May of 1994, however, Woodrow developed double pneumonia and passed away on Memorial Day. Soon after, it became apparent that Emilia was not able to live alone, so Theodore and Virginia decided to put her house on the market, thinking it would take a long time to sell, during which time they could make a plan about what to do with their mother. The market surprised them, however, and the house sold in a week. On top of that, right at about that time, Theodore’s wife, Janice, passed away very suddenly, throwing him into debilitating grief.

Meanwhile, Virginia was also tied up with personal concerns in Phoenix and could not return to Chicago to help find some sort of placement for her mother. Desperate, Virginia called Emilia’s brother, Bart, and his wife, Dorothy, who were still living on their own in the Chicagoland area. Though Bart and Dorothy were themselves elderly, they agreed to help and asked their son, Steve, to go pick up his Aunt Emilia and temporarily admit her to a nursing home until Virginia could come and find a permanent solution for her.

Emilia agreed to accompany her nephew, Steve, to the nursing home, though she even now insists that she does not require care. She is having a hard time adjusting to the home and believes her time here to be temporary. For this reason, she does not want to make any relationships or join in any activities. She appears on edge and pessimistic much of the time. She has a very dry sense of humor, which is usually lost on the other residents, but which the staff find funny. She is alert, but she still seems to be grieving for Woodrow, whom, she says was truly her best friend. “People thought we married too quick,” Emilia says, “but we proved them wrong. We were always meant to be together.”

(Originally written: October 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post They Met in October and Married in February! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 25, 2023

“They Don’t Know How Much We Love Each Other.”

Anton Lungu was born near Brasov, Romania on July 22, 1936 to Ciprian and Ileana Lungu. Ciprian was a soldier, and Ileana cared for their four children. Anton only went to the equivalent of seventh grade before he quit to work at a construction job. He stayed in construction his whole life, except for the two years he spent in the Romanian army. He served his time and even became an officer after attending a special training school. Once released, he returned to construction work.

Anton Lungu was born near Brasov, Romania on July 22, 1936 to Ciprian and Ileana Lungu. Ciprian was a soldier, and Ileana cared for their four children. Anton only went to the equivalent of seventh grade before he quit to work at a construction job. He stayed in construction his whole life, except for the two years he spent in the Romanian army. He served his time and even became an officer after attending a special training school. Once released, he returned to construction work.

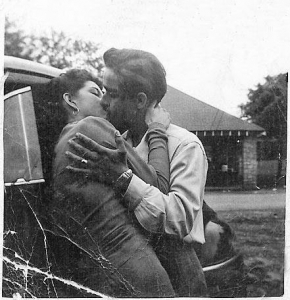

As a young man, Anton was apparently very handsome and popular. He had a motorcycle, a leather jacket and lots of girlfriends. He did not really fall in love, however, until he was 28 years old when he happened to meet the daughter of his boss. The girl’s name was Bianca Ardelean, and at the time that they met, she was only 17 years old. From the moment that he met her, Anton spent every day trying to persuade Bianca to go for a ride with him on his motorcycle, and each time she would refuse. One day, however, she finally said yes. Delighted, Anton devoted the whole day to her, spoiling her and giving her gifts and then, according to family legend, refused to bring her back home! At the end of the day, he proposed to her, and she said yes, so they drove off to elope.

Unfortunately, however, their plan was foiled. Since Bianca was still a minor, she was required to have her parents’ permission to marry, so they were turned away from the registrar’s office. In their own eyes, however, they were “married” and found a place in town to stay for the night. They then found an apartment, where they proceeded to live as man and wife. When Bianca’s father finally discovered his daughter’s whereabouts, he was furious, but Bianca refused to leave, saying that she was Aton’s “wife.” Anton continued to work construction, and Bianca cared for the two children that eventually came along: Bogdan and Crina. It was not until Crina was seven that Anton and Bianca finally legalized their marriage.

Crina reports that her father idolized her mother. He spoiled her constantly and often claimed that Bianca was “the greatest woman in the world,” and that no one else even came close. Crina says that her parents were completely devoted to each other and that they had a very happy marriage.

In the early days of their relationship, Anton developed a pattern of working very hard at a job, saving money, and then quitting so that he and Bianca could spend weeks at a time together—going to the movies, going on picnics and taking long walks. When their first child, Bogdan, was born, however, Anton became more responsible and stopped quitting jobs. He began working fourteen hours a day, rarely took a vacation, and did everything for Bianca and his two children. Crina says that her father was a very hard-working, passionate man who was full of energy and life. He loved gardening and painting, and he never failed to clean the house from “top to bottom” every Sunday. Though he was passionate, he was never angry, Crina reports. “He never raised his voice to us, never screamed, yelled, swore or spanked.” His philosophy, she says, was that a person could be talked to rationally and be won over through kindness.

In 1984, when Anton was 48 years old, he decided that the family should leave Romania and move to the United States. Bianca had a sister, Anca, who had been living in America for twenty years and who would periodically return to Romania to visit family and friends. The Lungu family loved hearing Aunt Anca’s stories about her life in America, and they would sit enraptured, listening to her tales. After one particularly nice visit from Anca, Anton decided that they, too, should move to America—that it would be good for the children to live there. Crina says that her father was always up for an adventure and that this seemed like “a wonderful one to undertake.”

Thus, in 1984, Anton moved the family from Bucharest to Chicago, which is where Anca was living. They all bought a house together, and Anton found work in construction, just as he had in Romania. For the most part, the family enjoyed their new country and remained very, very close.

In 1991, however, Anton began experiencing severely debilitating headaches. He finally went to the doctor, who diagnosed him as suffering from an aneurysm. Anton was rushed into surgery, but suffered a stroke immediately following it, which left him in a coma for eight months. During those long months, Bianca rarely left his side. Eventually, Anton awoke from his coma, but he could not speak. Then, after several weeks, he began speaking in perfect English, with no accent at all, and with perfect grammar and diction. It was extraordinary, and no one could explain it, even the doctors. This lasted only a brief time, however, before he lost this ability and oddly went back to speaking Romanian, apparently with no knowledge of his ability to speak perfect English.

Anton was eventually allowed to go back home, with the family taking turns caring for him around the clock. Unfortunately, the situation became worse when Bianca received news that her father back in Romania was dying and that he was asking for her to come back for one last visit. Bianca was very torn about what to do, considering the sometimes rocky relationship she had with her father ever since she ran off to marry Anton. She desperately wanted to make her peace with him, but she felt she could not possibly leave Anton. Eventually, Bogdan and Crina made the decision for her and insisted that she go back to Romania, promising that they would care for Anton in her absence.

Bianca finally agreed to go, but almost immediately upon her departure, Anton began to go “down-hill.” He had already been suffering from confusion and obsessive thinking, but it got worse without Bianca constantly by his side. In her absence, he began to have increasing episodes of shouting and screaming, which was completely out of character for him, and he refused to let anyone help him, even Bogdan and Crina. In desperation, his children called his doctor, who then arranged for Anton to be temporarily placed in a nursing home until Bianca could return.

Anton has not made a very smooth transition to the facility and constantly asks for Bianca. Finally, Crina told him that Bianca is ill and in the hospital. They do not dare tell him that Bianca is in Romania, as they feel this would push him over the edge, as he constantly begs to be taken back there himself. Bogdan and Crina visit daily, counting down the days until their mother returns from Romania. Once she is back, they plan to take Anton home, where his dog, Charlie, is apparently pining away for him. The staff have cautioned them that removing Anton is very unrealistic because of the level of care that he requires, but, Crina says, “they don’t know how much we love each other.”

(Originally written: October 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “They Don’t Know How Much We Love Each Other.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 18, 2023

“An Amazing Zest for Life!”

Wilma McDonald was born on April 10, 1910 in Chicago to Lech Kaszubski and Berta Kaluza. Not much is known about the origins of Lech and Berta. It is believed that they were both born in Chicago, though their parents had been born in Poland. They did not call themselves Poles, however, but Kashubs, which is apparently an ethnic Slavic group descended from medieval Pomeranians. Whatever their exact origin, Lech and Berta married young and attempted to make a life in Chicago. Lech started out building truck bodies back in the days when they were still crafted of wood. Later in life, he decided to open a restaurant near Milwaukee and Devon. The restaurant was located right between two cemeteries, so a big source of Lech’s business was funeral dinners. Berta, meanwhile, was a housewife who cared for their three children: Wilma, Cecelia, and Albert.

Wilma McDonald was born on April 10, 1910 in Chicago to Lech Kaszubski and Berta Kaluza. Not much is known about the origins of Lech and Berta. It is believed that they were both born in Chicago, though their parents had been born in Poland. They did not call themselves Poles, however, but Kashubs, which is apparently an ethnic Slavic group descended from medieval Pomeranians. Whatever their exact origin, Lech and Berta married young and attempted to make a life in Chicago. Lech started out building truck bodies back in the days when they were still crafted of wood. Later in life, he decided to open a restaurant near Milwaukee and Devon. The restaurant was located right between two cemeteries, so a big source of Lech’s business was funeral dinners. Berta, meanwhile, was a housewife who cared for their three children: Wilma, Cecelia, and Albert.

Wilma went to school until eighth grade and then worked at the family restaurant until she was sixteen. At that time, she asked her parents if she could quit and instead got a job at M. Snower as a seamstress doing what was called “piece work.” Lech was reluctant to give up one of his best workers, but Berta convinced him to let Wilma try something else. At M. Snower, each girl had a minimum number of garments that she needed to produce in order to receive her base pay. Anything the girls produced beyond the minimum got them a bonus. Wilma really enjoyed this job, so much so that she stayed at the company for fifty-four years, retiring when she was seventy! Every day of her work week, she took two buses and the el to get there.

As a young woman, Wilma lived for dancing. She loved to hear the big bands at the Aragon, Trianon and the Rainbow. It was at one of these dance halls that she met Martin McDonald, whom she eventually married. Marty had a job unloading mail off of boxcars, and the couple lived on McLean Avenue. They had one child, Russell. When the war broke out, Marty joined the army and managed to make it back safe, only minimally wounded, after two years of active duty. He got his job back unloading the mail, but he and Wilma were not the same. They began fighting a lot and could no longer see eye-to-eye on anything. Finally, when Russell was eight, the couple divorced. Wilma lost contact with Marty and supported Russell alone on her wages as a seamstress.

Russell reports that his mother was always on the go. She had “tons of hobbies” and was always full of life. Besides music—big band in particular—Wilma also loved the movies and went religiously, every Sunday, to the cinema. She was also obsessed with crocheting afghans and knitting doilies and was constantly doing this in her spare time, even to age eighty-two. She was an avid reader, her favorite genres being mystery and romance, and she would check out at least six books at a time and return all of them, finished, after two weeks.

Perhaps the biggest love of her life, though, was her grandson, Joseph. In 1972, when Joseph was born, Wilma moved in with Russell and his wife, Eva, and helped to take care of Joey, even though she was still working herself. She was a huge part of Joey’s life and was always interested in what he and his friends were up to. Even as teenagers, if Joey had friends over for a BBQ, Wilma could always be found in the midst of them, having fun and joking with them. She genuinely loved all young people in general, and enjoyed spending time in their company.

Up until the age of sixty-five, Wilma had never traveled beyond the Chicago city limits. But upon her sixty-fifth birthday, she decided to take up traveling and went on bus trips all over the United States and even made it to Hawaii. Over the years, she has belonged to several parishes: St. Stanislaw, St. Sylvester, and St. Cornelius, but never joined any groups or ministries in any of them, even in recent years, because she thought everyone in those groups were too old!

Wilma continued working until she was seventy, but even after she retired, she kept up her very active lifestyle—which included smoking and drinking—until she was around seventy-seven, which is when she experienced the first of her “spells.” She says she was at the library when the first one occurred. Russell came and got her and took her to the emergency room, where she had “every test known to man.” Nothing significant was found, but she continued to have several of these “spells” over the next six or seven years, each time experiencing a small loss in cognition as a result.

Recently, one of these spells caused her to fall, and she broke a hip. While in the hospital recovering, she fell and broke the other hip. Much to their great sorrow, Russell and Eva, who is experiencing her own serious health issues, felt they could not care for Wilma any more at home, especially considering her two broken hips.

Russell, who is not able to visit often because most of his time is taken up caring for Eva, describes Wilma as a very strong woman who never let things bother her. He thinks that one of the reasons she liked to keep so busy was so that she wouldn’t have to dwell on the past or current worries. “She has an amazing zest for life,” Russell reports. “Nothing ever slowed her down.” She prayed novenas often and surrounded herself with a lot of friends as a way of coping, he says. Her grandson, Joe, who was such a big part of her life, lives in Montana now and has not yet been to see her since her admission.

Overall, Wilma is a very alert, pleasant woman who enjoys all aspects of the nursing home. Only occasionally is she disoriented and confused, during which times she politely asks the staff to call Russell or Joey to come and get her. Her favorite activities are bingo, game night, and big band hour. She loves talking to the other residents and is very outgoing.

(Originally written: November 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “An Amazing Zest for Life!” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 11, 2023

She Was Born and Lived in the Same Apartment for Over 80 years!

Edith Wojewodika was born on February 7, 1915 in Chicago. Her parents were Eluf Akselsem and Britta Dam, both immigrants from Denmark who met in New York shortly after arriving in America. They married three weeks later, much to the surprise of those who knew them. Everyone said they were crazy and that it wouldn’t last. Eluf and Britta were happy, though, and decided to move to Chicago, where they both found jobs cleaning offices for the telephone company. They found an upstairs apartment in a two-story bungalow on Ohio Street, which they rented for many years until they could afford to buy the building itself from the money they managed to save.

Edith Wojewodika was born on February 7, 1915 in Chicago. Her parents were Eluf Akselsem and Britta Dam, both immigrants from Denmark who met in New York shortly after arriving in America. They married three weeks later, much to the surprise of those who knew them. Everyone said they were crazy and that it wouldn’t last. Eluf and Britta were happy, though, and decided to move to Chicago, where they both found jobs cleaning offices for the telephone company. They found an upstairs apartment in a two-story bungalow on Ohio Street, which they rented for many years until they could afford to buy the building itself from the money they managed to save.

It is said that Britta had nine miscarriages before she was able to give birth to five children: Anna, Otto, Ruben, Viggo and Edith. Britta continued working as a cleaner on the night shift even after all the children were born, while Eluf worked the day shift so that someone was always at home with the children. This arrangement worked until Eluf suddenly died of a heart attack at age 48.

Though Edith was only in seventh grade at the time, she quit school to get a job to help bring in money for her mother. She lied about her age and used her sister’s name to get a job at a factory making bobby pins. She worked there for several years until she quit to work in other factories.

In 1936, when she was 21, Edith married the boy next door, Paul Wojewodika, whom she had known all her life. Though he was four years her senior, they had always been friends. Edith says, “I never thought of him in a romantic way,” so she was very surprised when one day he asked her out on a date. She didn’t know what to say, so she said yes, not knowing what to expect. Paul told her that he had been in love with her “forever” and wanted to marry her. Edith wasn’t sure how she felt at first, but agreed to go on more dates with him. Eventually she fell in love with him, too, and they were married.

After the wedding, Britta decided to move into the downstairs apartment of the bungalow, as she had developed arthritis and found climbing the stairs to be very painful. All of the other siblings had already married and left, so Edith simply remained in the upstairs apartment and Paul moved in. Paul and Edith lived in that same apartment their whole married life and made many changes to the structure over the years, including installing a water heater and bath tubs.

Paul worked for Western Electric until it closed down, at which point he got a job at a plating company. Upon getting married, Edith did not go out to work. She miscarried several times and then began having “complications.” Finally the doctors advised a hysterectomy, which was very hard for Edith to accept. She really wanted children, but it seemed it was not to be. Eventually she grew bored of staying home alone, so she got a job at American Color Type making Christmas cards.

Edith was very active in her parish of Holy Innocents, though she was also involved at the nearby St. John Cantius, as well. She was likewise the member of the Welfare Club, which helped orphans needing clothes for their First Communion or other holiday occasions. She loved to bake and was actually quite famous in the area for her carrot cake. She loved to go dancing, though Paul was not too keen. Often he would take her to a dance hall, where she would dance with other people. Apparently Paul did not seem to mind this, frequently telling her, “I don’t mind who you dance with, just as long as you remember who you came with!”

When Edith’s mother, Britta, passed away, Edith’s sister, Anna, and her husband, Oscar, moved into the downstairs apartment. Not long after, Anna died as well, so Dorothy, Anna and Oscar’s daughter, moved in to help care for Oscar, who needed a lot of help and could not be on his own. Edith says it was a blessing because the very next year, Paul died, too, and it was a very great comfort to have her neice, Dorothy, living just below. Even so, Edith took Paul’s death very hard, as they were terribly close. They had known each other almost all their lives and had done everything together. Edith describes Paul as being a very sweet, gentle, loving man.

After his death, Edith continued on her own, going to her various groups at Holy Innocents until she fell several times in one year. Dorothy tried to get her to move in with her and Oscar, but Edith refused, not wanting to burden her niece. It was at her own insistence, then, that she be admitted to a nursing home, and if she is sad because of it, she does not let on. In September of 1995, she left the apartment on Ohio Street, the place where she had been born and where she had lived for over eighty years.

With incredible positivity and hopefulness, she is trying her best to adjust to her new home. She says she has always “taken things in stride” and gets a lot of comfort from prayer. Being in a nursing home is “not so bad” she says. “I already have a lot of friends.”

(Originally written: September 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Was Born and Lived in the Same Apartment for Over 80 years! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 4, 2023

“A Pillar of His Community”

Leonard “Leo” Frazier was born on October 7, 1906 on a farm in Minnesota to Lewis and Marion Frazier. Lewis was born in Minnesota, and Marion was a German immigrant. Together they had eight children, of whom Leonard was the youngest.

Leonard “Leo” Frazier was born on October 7, 1906 on a farm in Minnesota to Lewis and Marion Frazier. Lewis was born in Minnesota, and Marion was a German immigrant. Together they had eight children, of whom Leonard was the youngest.

When Leo was only three years old, his father died. His mother eventually remarried and had two more children. Leo’s stepfather was apparently very abusive to him and to his mother, and Leo only went to school until roughly the 3rd grade before he was made to work on the farm. As he grew older, he also worked as a hired hand on surrounding farms and even worked, as a young teen, on a ranch in Montana for a while with his brother, Arthur, who had found work there as a blacksmith.

When he was about seventeen or eighteen, Leo decided to make his way back home from Montana, but found work along the way in Chicago, working construction. He decided to stay and worked to get himself established before finally completing the trip back to Minnesota, determined to rescue his mother from his abusive stepfather. Marion apparently did not need much convincing, and she escaped with Leo. Together, they bought a small house in Oak Park, Il. though it was a struggle to keep it, especially once the Great Depression hit. Eventually, however, almost all of Leo’s brothers migrated down to find work in the city and lived in the house with Leo and Marion.

In the 1930’s, Leo and his brothers formed the Frazier Brothers Construction Company. Leo worked very hard, mostly doing remodeling work, and employed a man, Fred Schneider, to build cabinets in the garage behind their house in Oak Park, which Leo would then install in various homes. Eventually, Leo formed a separate company called Frazier Home Utilities Company, which basically consisted of his arrangement with Fred to build cabinets as well as a lumber supply company of sorts.

When the war broke out, however, Leo found himself too busy to install the cabinets Fred was building. Instead of remodeling and home construction, Leo and his brothers found themselves building barracks at Fort Knox and also did work for Chrysler at Great Lakes, which was producing products for the war effort.

After the war was over, business boomed for the Frazier Brothers Construction Company and Leo was swamped with work. He still managed, however, to build a handful of homes himself from the ground up, many of which can still be seen today in Villa Park.

When Leo was twenty-four, he was set up on a blind date with a young woman, Lucille Cotter, who was four years his junior. The two of them hit it off right away and got married in 1930. They had two children: Sidney and Sissie, and Lucille acted as the bookkeeper for both of Leo’s companies. After the Depression, Leo’s brothers eventually married as well, and one by one, they left the house until only Marion was left. She continued living with Leo and Lucille until 1950 when she fell and broke her hip. Upon her release from the hospital, however, she needed so much care that Leo was forced to put her in a nursing home. She died soon after at age eighty-three.

Leo and Lucille apparently had a very happy marriage, one of their favorite hobbies being square dancing. They became friends with a couple who were famous in the region as “callers”—Lulubell and Scottie McPherson. The four of them remained friends for many years, and Leo even did work on their house in Oak Park for them.

Besides square dancing, Leo’s other passion in life was horseshoes. Apparently, Leo traveled all over the country—and the world!—competing in competitions and won over 100 trophies. Leo’s son, Sid, says that he rarely saw his father when he was growing up, as he was always working or away at a horseshoe competition. Leo was also an active member of the “Freedom Through Truth Foundation,” which was a civic group that focused on educating people about how money is created, circulated and used by the government or big businesses to keep people in debt.

In 1984, Leo felt it was time to retire and accordingly dissolved Frazier Home Utilities Company, but he allowed his nephews to take over the Frazier Brothers Construction Company. About four or five years later, however, it closed, too.

In 1993, Lucille passed away, which is when all of Leo’s troubles began, says Sid. Lucille’s death was terribly hard on Leo, as they had been married 63 years. He became depressed and angry and then began to slip mentally. Finally, it was decided that Sid would move in with his father for a time, hoping that if he could provide balanced meals for him, his confusion might get better. Even under Sid’s supervision, however, Leo got progressively worse, so Sid and his wife, Jean, finally arranged for Leo to be admitted to a nursing home. Leo’s daughter, Sissie, lives in Vermont and is not a part of his care plan, though she calls several times a week to talk to him.

Leo is able to communicate at times, but he remains very confused. He spends most of his time wandering the halls and periodically attempts to leave the facility. He is easily redirected, however, and does not become agitated. Frequently he asks for Lucille or Sid. Sid visits as often as he can and attempts to play checkers or chess with his father, which Leo used to love and which was one of the few things that he and Sid shared as Sid was growing up. At first, Leo seems enthused to play but then quickly becomes distracted.

Sid ruefully reflects that despite the fact that Leo wasn’t the most active, present father, he was was “a real pillar of his community. Everyone respected him.”

(Originally written: February 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “A Pillar of His Community” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.