Michelle Cox's Blog, page 10

September 29, 2022

“Stay With Me…”

Michal Havelka was born on March 28, 1898 in Chicago to Michal Havelka, Sr. and Ivana Beran, both immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Michal’s father worked as a house painter, and the family lived on Pulaski Avenue. Michal says he can still remember when Pulaski was a dirt road and horses and buggies were still the main means of transportation. Originally, there were six children in the family, but the two oldest boys died in the flu epidemic, which left only four: Martin, Agatha, Michal, Jr. and Robert.

Michal Havelka was born on March 28, 1898 in Chicago to Michal Havelka, Sr. and Ivana Beran, both immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Michal’s father worked as a house painter, and the family lived on Pulaski Avenue. Michal says he can still remember when Pulaski was a dirt road and horses and buggies were still the main means of transportation. Originally, there were six children in the family, but the two oldest boys died in the flu epidemic, which left only four: Martin, Agatha, Michal, Jr. and Robert.

Michal went to high school and started working in various print shops around the city before he began working at Commerce Clearing House on Peterson, where he remained for over 42 years. Michal says that he had a good reputation there as being a hard worker and is very proud of the service award he was presented with when he retired.

Oddly, only one of the Havelka children married. Their mother, Ivana, made them all promise that they would never leave her. “Stay with me,” she begged them over and over. Only Martin broke his promise, marrying a girl and moving to Colorado Springs where he worked as a printer like his older brother, Michal. The rest of the family remained with their mother at the house on Pulaski and then in Berwyn, where they moved when their father died at age 78. When asked if he regretted never getting married, Michal responded, “No, because you might pick up a lemon.”

Michal says he and Robert didn’t mind so much not getting married, but it was very hard on their sister, Agatha. She wanted to marry her high-school sweetheart, but Ivana put so much guilt on her that Agatha eventually gave him up and instead stayed home to take care of her aging parents. Michal says she took a long time to get over it and was depressed for years.

For his part, Michal dealt with his mother’s strange wishes by taking up a life of travelling whenever he got a vacation. In all, he visited thirteen European countries as well as Hawaii, Mexico, Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Cuba and Jamaica. He also travelled extensively with Robert throughout the United States, especially enjoying the western states. His favorite place of all, though, he says, was Hawaii.

Michal’s other love in life was baseball. He spent many years on a team until he was one day hit in the back of the head by a ball, which caused permanent hearing damage in his left ear and put an end to his playing. He also a devoted member of the Elks and enjoyed reading the paper, watching westerns, following the New York Stock exchange and listening to big band music. Slowly the years passed by and everyone died but him. His mother died of heart failure in her mid-eighties, Agatha died of breast cancer, Martin died in a nursing home for printers in Colorado Springs, and Robert died of a heart attack.

Michal was able to live alone until age 96 when he fell at home and lay for two days before his neighbor discovered him. He was taken to a hospital and eventually discharged to a nursing home where he was able to get around with a walker and a cane. “It’s not a bad place,” he would often say. When asked if he would have done anything differently, his response was: “I suppose not. It wasn’t really such a bad life.”

(Originally written: September 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Stay With Me…” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

September 23, 2022

“We All Have Questions…”

Evelyn Feldman was born on October 31, 1922 in Chicago to Russian Jewish immigrants, Aron and Riva Mayer. In Russia, Aron worked as a tailor, but once in Chicago he went into the “junk business,” which involved going around with a horse and wagon collecting, buying and selling used goods or metal scraps. Riva stayed at home and cared for their five children, of which Evelyn was the youngest.

Evelyn Feldman was born on October 31, 1922 in Chicago to Russian Jewish immigrants, Aron and Riva Mayer. In Russia, Aron worked as a tailor, but once in Chicago he went into the “junk business,” which involved going around with a horse and wagon collecting, buying and selling used goods or metal scraps. Riva stayed at home and cared for their five children, of which Evelyn was the youngest.

Evelyn attended high school and then got a job downtown working for Collier’s publishing, which mainly published sports and racing magazines. She remained with them a few years until they closed down and then went to work for a finance company called Madison Discount Co. While she was there, her mother, Riva, passed away from a stroke at age 54, which left her home alone with her father, as all of her siblings had already married and left.

As it happened, the Mayer family had always been very close to the Feldman family, one of Evelyn’s older sisters being best friends with one of the Feldman girls, though all of the children played together at family functions. In fact, when Evelyn was just seven, she and her friends and one of the Feldman girls formed a club called “The Little Women,” in which they promised to be friends forever. Upon finding out about the secret club, William Feldman, the oldest of the Feldman clan, teased them and said they should instead call themselves “The Little Pests.”

It was very surprising to Evelyn, then, after WWII broke out, that William, five years her senior, asked her to write to him while he was away, having immediately joined up. She agreed, however, and through their letters, they fell in love. When he came back from the war, they were married on June 1, 1947.

The young couple got a small apartment, and William went into the junk business with Aron, though by now they had a truck instead of a horse and wagon. Evelyn got pregnant right away, but later miscarried the baby, which was very devastating for them both. Soon she was pregnant again and had Polly and later, Paul.

After a number of years, William became the foreman for the streets and sanitation department and then a precinct captain for his ward. Evelyn says that absolutely everyone knew Bill and that he considered everyone in his ward his personal friends and would do anything for them. He worked constantly for the ward, almost as if “he was married to it,” laughs Evelyn.

She, too, however was very active in the community. Besides caring for Polly and Paul, she was a volunteer at the Ruth Lodge Home for Spastics and also volunteered at the Women’s Defense Corp, where they sold bonds and stamps and worked in hospitals for servicemen. Evelyn says that they were very busy, but she and Bill managed to spend a lot of time together and that they loved each other very much. “He was a good man,” Evelyn says, “kind to everyone.”

It was hard then, when Bill died at age 71. But Evelyn’s grief was doubled when her daughter, Polly, died just six months later. Polly was 38 years old and living with Evelyn and Bill, caring for them and working at a menial job. She was extremely close to both of her parents, and some said that she just couldn’t face Bill’s death, wanting to die herself. She developed a cold of sorts and stayed home from work for a few days. She refused to go to the doctor, and when Evelyn went in to check on her one morning, she found she found her cold and clammy. Evelyn immediately called the ambulance, but Polly died en route. Evelyn says that not only did she lose a daughter that day, but she lost her very best friend.

Unsure of what to do next, Evelyn put her townhouse up for sale, thinking it would take about a year to sell, which would give her time to plan out what to do with the rest of her life. The townhouse sold immediately, however, forcing her to move in with her son, Paul, and his family. It was meant to be a temporary arrangement, but then Paul remodeled the house and built an in-law apartment for her to stay permanently.

As time has go on, however, Evelyn has started to have a number of health problems, including a cerebral hemorrhage, which she survived she says because while it was happening, she fell down the stairs, cutting her head open and releasing some of the blood. Recently she broke her shoulder and has been admitted to a nursing home for rehabilitation. She is hoping to go back to Paul’s, but Paul does not see this as realistic.

Meanwhile, Evelyn is an enthusiastic participant in the home’s activities, though she enjoys sitting and talking with people the most. She is very bright and intelligent and can talk about almost any subject. She is extremely pleasant, despite the loss of her beloved Bill and Polly. She says she still misses them, but adds, “We all have questions. There are no answers.”

(Originally written: February 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “We All Have Questions…” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

September 15, 2022

“For God’s Sake, See Reason!”

Lois Wright was born on March 23, 1911 in Chicago. Her parents were Thomas Wright, who was on the Chicago Board of Trade, and Ida Carroll, who stayed home to care for their eight children: Pearl, Thomas Jr., Joseph, Roger, Frank, Mary, Lewis and Lois. Three of the boys – Thomas Jr, Frank, and Lewis – died in the flu epidemic before Lois was even born. Shortly after, Ida got pregnant again and, still grieving for her baby boy, Lewis, hoped that she would have another boy so that she could name him Lewis, too. Disappointingly, however, it was a girl, so they named her Lois as the next best thing.

Lois Wright was born on March 23, 1911 in Chicago. Her parents were Thomas Wright, who was on the Chicago Board of Trade, and Ida Carroll, who stayed home to care for their eight children: Pearl, Thomas Jr., Joseph, Roger, Frank, Mary, Lewis and Lois. Three of the boys – Thomas Jr, Frank, and Lewis – died in the flu epidemic before Lois was even born. Shortly after, Ida got pregnant again and, still grieving for her baby boy, Lewis, hoped that she would have another boy so that she could name him Lewis, too. Disappointingly, however, it was a girl, so they named her Lois as the next best thing.

Lois, it seems, was surrounded by death all her life. When she was just thirteen months old, her father died of “dropsy,” or “water on the lungs.” Her mother, devastated and overwhelmed by his death, decided to give baby Lois to Pearl, who had already married and moved out, saying bitterly, “You always wanted a little girl; well, here’s your little girl!” Unfortunately, however, Pearl died in 1921 when Lois was just ten, and though Lois looked to Pearl’s husband, Earl, as a father figure and her cousin, Doris, as a sister, she was ripped from them when Earl sent her back to live with Ida and her biological siblings. Tragically, in 1924, Ida died, too, leaving the four siblings – Joseph, Roger, Mary and Lois – alone. They lived together for the next 35 years.

The three elder siblings all got jobs, and Lois, being the youngest, went to high school. When she graduated, her siblings scrimped and saved to send her to college. She was able to complete one year at Northwestern, during which she studied personnel, before she had to give it up, as the struggling family just couldn’t afford it anymore. After she quit, Lois got a job as a filing clerk at J. S. Paluch. She worked there for 28 years, eventually working her way up to being a production manager.

None of the Wrights married, including Lois, but she did, once upon a time, fall in love. Already in her thirties and beginning to think that romance and marriage had passed her by, she happened to meet a young lawyer, Arthur Cunningham, whom she liked very much. They began dating and fell in love, but their relationship, it seemed, was doomed because she was a Catholic and Arthur was a Protestant. Lois’s siblings were furious with her for dating a Protestant and begged and pleaded with her to give Arthur up, as her life would be nothing but misery, they warned, if she pursued a marriage with him. Arthur’s family, apparently, was no different and likewise urged him to break it off.

The situation came to a crisis when WWII broke out, and Arthur had to leave for the navy. Still in love, they contemplated getting married before he went, but both families begged for them to “for God’s sake, see reason,” and wait until he came back. In the end, Lois and Arthur obeyed their families’ wishes and agreed to postpone the wedding until Arthur came home on leave in September of that year. The wedding was not to be, however, as Arthur was killed in Germany in August. Lois was plunged into despair.

Both families instantly realized their terrible mistake and deeply regretted what they had done. Poor Lois grieved terribly for her lost love, though both families tried valiantly to make it up to her. Even Arthur’s mother tried to assuage Lois’s grief by taking her on long trips. Eventually, Lois says, she had to “get over it” and go on, but she never fell in love again.

When she was 62, Lois decided to retire early, though all her friends said she was crazy. Not listening to them, Lois calmly pointed out that her mother and most of her siblings had died from diabetes before they reached sixty, and she wanted to have some fun “before her number came up.” Thus. she quit her job and pursued her hobbies. She was a lifelong member of various church committees, the girl scouts and loved roller-skating and swimming. Her real passion, however, was travel. Over the years, she traveled to every state except Hawaii, which she missed only because she couldn’t find anyone to go with her and she didn’t want to go alone.

After a series of recent falls, Lois decided to go to a nursing home to live and sought the help of her “nieces,” who are actually the daughter and granddaughter of her cousin Doris, whom she grew up with and whom she still calls her “sister,” having stayed close all these years despite being separated at age ten.

Lois is an incredibly alert, intelligent, articulate woman who loves conversation and activities. She has adjusted well to her new surroundings and is interested in her roommate and all that the facility offers. She is a very sweet, humble, delightful woman who has tried to make the best of what life has offered her.

(Originally written: May 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “For God’s Sake, See Reason!” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

September 7, 2022

Kindred Souls

Irene Miller was born on November 4, 1913 in Chicago to Slawomir Kotwica and Maria Pestka, both of whom were Polish immigrants. Slawomir made a living as a tailor, and Maria cared for their eight children: Louise, Josie, Ralph, Jack, Louis, Irene, Dick and Kenny. Maria actually gave birth to an additional three babies, but they died shortly after birth. Though it wasn’t the custom at the time, she insisted on naming them: Edna, Catherine and Leon.

Like her older siblings, Irene attended grade school at St. Mary of the Angels, where she did very well. She excelled in art, however, and was thrilled when she won an art scholarship given by a sorority at Northwestern University to attend the Fine Arts Academy in Evanston instead of going to high school. Though hesitant at first, Slawomir and Maria allowed Irene to accept the award, and Irene attended for one year. Shortly after completing her freshman year, however, Irene became very ill and almost died. Apparently her appendix burst, and she suffered horribly from peritonitis. The school agreed to hold her scholarship for one year, but even after that amount of time, Irene was still not recovered enough to return, so she had to relinquish it, much to her sorrow.

After a couple of years, Irene was strong enough to be able to work again and got a job in a factory, which she hated. She went to Wells High School at night to earn her diploma, which she eventually achieved, and then got a job as a bookkeeper. Irene never returned to art school, but she didn’t forget her time there and was very proud of having attended, even for one year. She kept all of her paintings and hung them up at home and liked to show them off to whoever happened to stop by.

After her dreams of becoming an artist were dashed, Irene instead began to dream of romance. Though she worked in an office with many men, none of them seemed to interest her. One night, however, when she went out dancing with some friends, she met a dashing young man by the name of Joe Miller, whom, she said “was a fantastic dancer.” When Irene eventually brought him around to meet her family, they were, for some reason, not as impressed with him as Irene seemed to be. Stubbornly, however, Irene insisted that Joe was “the one,” and when he suggested that they elope, she agreed, though they had only known each other for a few months.

After their hasty marriage, Joe and Irene got a small apartment on Hermitage, and Irene became pregnant almost immediately. By the time she gave birth, however, Irene’s relationship with Joe had already soured. They decided to divorce, though Irene does not elaborate on why, and Joe left town. Devastated, Irene took her baby girl, Clara, and went back to live with her parents.

Irene’s mother, Maria, was apparently a very wise, insightful woman who was, Irene claimed many times, “ahead of her time.” Though Maria was sympathetic and comforting to Irene, she urged her youngest daughter to get back on her feet, to work and save money so that she could get her own apartment and be independent, believing that this would be the best for Irene. Tragically, however, two months after Irene and Clara moved in, Maria died.

Irene did not forget her mother’s words of advice, though, and after grieving for several months, finally decided to act on them. She got a job and saved and saved and saved until she had enough to finally move out of her father’s house. By this time, however, Clara was almost seven years old, and Irene worried about what she would do with Clara while she was working.

At that time, almost all school children went home for lunch, which was not a possibility for Clara since Irene needed to work all day. Irene therefore searched around for a school that provided a hot lunch program, which was a rarity then, and finally found one at Holy Family Academy. The tuition was higher, but Irene felt it was worth it. She then began looking for an apartment within walking distance of the school and also took a different job at a company called Celmers, which was within walking distance of the school and their apartment, though it meant taking a cut in pay.

Irene then set out to prepare for any contingency. She made arrangements with the nuns at Holy Family that if anything should ever happen to herself, Clara could stay there with them until someone from her family could come and claim Clara. Irene walked Clara to school every day and left work each afternoon to walk her home to the apartment, which was above a shop. Having safely deposited Clara at home, Irene would then walk back to work, where she stayed until evening. Likewise, Irene also made an arrangement with the shop owners below the apartment, asking them if it would be alright for Clara to sit in the shop if she needed help or was simply scared.

According to Clara, it was a difficult transition to make in many ways. She was quite used to living with her grandfather and aunts and uncles in a big house, where there were always people coming and going and visiting, so it was difficult for her to be in a small place with just her mother for company. Clara suspects it must have been difficult for her mother as well, as she was constantly worried and had many digestive issues because of her perpetual stress. Likewise, she had an elaborate prayer ritual which she followed day and night.

Eventually, however, Irene began to find her feet and create the life for herself that perhaps Maria, her mother, had envisioned for her. Irene began to enjoy having friends over to discuss current events, philosophy, religion, and psychology. Also, she never lost her passion for art, her creativity spilling out into any area it could. She loved decorating the house, reading, doing artwork for her church, crocheting, and sewing. She made many of her own and Clara’s clothes and even sewed curtains and bedspreads. She was always dressed very stylishly and took special care with makeup, Clara says, though she was never interested in men or dating again. In everything that she did, Clara adds, her mother had “a real flair” for color and pattern.

Irene’s favorite pastime, however, was simply being at home and spending time with Clara, whom she was utterly devoted to. The two of them were truly best friends, and Clara lived with Irene for years and years—long after she became an adult. “There was never a reason to leave,” Clara says. Apparently, the two were so devoted to each other that Clara even waited until her sixties before she herself got married, as she didn’t want to leave her mother. “We’ve always known we are kindred souls,” Clara says.

When Irene finally retired in the 1980s, she became more and more dependent on Clara. She began to suffer from a long list of ailments and had to have many surgeries, including corneal transplants to help her increasing blindness due to glaucoma. She then began to have a series of falls and became very disoriented and confused. Clara agonized for a long time about placing her mother in a home, but in the end, she saw no other choice. Clara, despite being a newlywed, remains faithful to Irene and continues to visit her daily, a beautiful tribute to the life they once shared.

(Originally written: October 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Kindred Souls appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

September 1, 2022

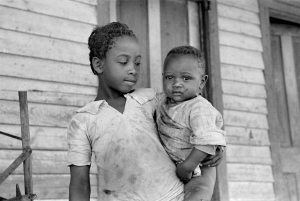

Sharecropper’s Daughter

Sadie Margaret Perez was born on January 21, 1931 to Mississippi sharecroppers, Leland Brown and Flora Jefferson. Flora often worked in the fields beside Leland despite the fact that she had fifteen children: Dwayne, Jeannette, Abraham, Lila, Della, Rosalie, Elbert, Forrest, Irma, Eula, Winnie, Sadie, Alton, Dewey, Merle, and Clinton. Sadie says that only seven children were ever living in the house at any given time, though, as the rest were out on their own.

Sadie was the youngest girl and was named by the man who owned the little grocery store in town. He happened to be making a delivery at the farm on the day Sadie was born and insisted that the new baby be named for his own daughter, Sadie Margaret. Even though they were white, his family was very kind to the Browns and sent a basket of fruit and candy to them every year at Christmas.

From a very little age, all of the Brown children were expected to work in the fields, and Sadie was no exception. When she was eight, however, she was sent back up to the house to learn cooking from her mother. School was a very sketchy affair. All of the white children on the surrounding farms were picked up every day by a school bus and taken to the town school. “Colored” children were forced to go to the country school, which, Sadie says, “was like having no school at all.” Apparently the teaching was very poor, and Sadie says Flora was better able to teach her children numbers and letters at home.

Near to the Browns lived a white sharecropper family, the Dicksons, though the oldest child, Annie, was “half black and half white.” Mrs. Dickson often told the neighboring children that Annie had “come out dark” because a bear had scared her while she was pregnant with her. None of the Brown children believed her, but they pretended to. Because she was bi-racial, Annie was not allowed to attend the town school with the white kids, so Mrs. Dickson taught her at home and the Brown children, too. Sadie says she learned a lot from Mrs. Dickson, but their “class” would frequently be broken up when Mr. Dickson came home drunk and called them awful names, though most of his anger was directed at poor Annie, who had become a good friend of Sadie’s.

When Sadie was just nine years old, a terrible incident occurred which she rarely rarely ever talks about. Sadie says that one summer day, she was at home watching her younger brothers while everyone else worked in the fields. At some point, the sixteen-year old son of the family who owned the farm rode up on his horse, forced his way into the house, and tried to rape Sadie. There was no one to hear her screams, but Sadie’s brothers, little though they were, managed to fight him off and he left. Sadie and the whole family were badly shaken, but they did not dare complain to the owners of the farm in fear of losing their place.

By the time she was thirteen, it was time for her Sadie to leave the farm, so Flora arranged for her to go live in Hattiesburg with her older sister, Jeannette, who promised to get Sadie some schooling. Instead, Jeannette arranged for Sadie to become a nanny for a white family. Sadie worked as a nanny for two years before appealing to her brother, Dwayne, in Chicago. Dwayne had apparently wanted Sadie to come live with him and his wife from the very beginning, but Flora was afraid his wife might mistreat Sadie. Flora eventually gave in, however, and sent Sadie to Chicago. Dwayne’s wife, it turns out, did not mistreat Sadie, but enrolled her in night classes to try to get her her high school diploma and also got her a job at a packing company, where Sadie worked for thirty-three years. She never did get her diploma.

Besides knowing Dwayne and his wife, Sadie also had cousins living in Chicago, whom she began to see quite often and whom she even went to stay with sometimes. One night, she was at a party given by one of her cousins when she was introduced to a young Mexican man by the name of Miguel Perez, who liked her immediately and proposed! Sadie was shocked and replied that they didn’t even know each other. “Yes,” Miguel apparently replied, “but I need a wife!” Sadie said she would think it over. Three weeks later, she married him in her cousin’s home.

When Dwayne found out about Sadie’s quick wedding, he was furious that she had married a Mexican, never mind the hastiness of it. “Why didn’t you tell me you were looking for a husband!” he shouted at her. “I would have found you one!” After he got to know Miguel, however, he actually liked him very much. Sadie says that her husband was very good to her and that they have always had a close relationship. Together, they had four children: Miguel, Jr., Monica, Gabriela, and Jorge. All are alive and well, except Jorge, who died at age twenty-nine from either a drug overdose or suicide.

After working at the packing house for thirty-three years, Sadie began working at the Salvation Army. She was an expert at crocheting and loved watching television and movies. Miguel took her to Mexico three times to meet his family, but Sadie says she did not enjoy it, as it was too hot. Other than that, they did not travel, except occasionally to Wisconsin to fish.

Over the years, Sadie’s health has continued to decline. She has suffered from asthma since she was a young girl, though no one knew at the time what it was or how to properly treat it. She has recently been in and out of the hospital for a variety of illnesses and surgeries. Each time she has been discharged home ,it has been harder and harder for Miguel to care for her, as his own health is now starting to go, as well. Also, not only does Sadie require skilled care, but her excessive weight makes it almost impossible for the family to lift or move her. Most recently, then, when Sadie was admitted to the hospital to have fluid around her brain drained, the hospital staff finally convinced the family to have her transferred to a nursing facility.

Sadie is making a relatively smooth transition to her new home, though she appears at times to be depressed. She does not spend much time interacting with other residents, but instead waits in her room for her family to visit. Sadie is a lovely woman to talk to and is very gentle. Despite everything that has happened in her life, she remains loving and forgiving. For every story she has about something hateful that happened to her, she will immediately tell one of love and optimism. She says that she has always “looked on the bright side of things” and has gotten through hard times with prayer.

(Originally written: January 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

*photo credit: Russell Lee

The post Sharecropper’s Daughter appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 25, 2022

She Overcame Her Stutter . . .

Annie Flemming was born on November 18, 1900 in a small town in Wisconsin. Her parents, Myrtle Jones and Howard Gilman, were of English and Irish descent. Howard worked in a flour mill, and Myrtle worked in a tailor’s shop and also cared for their four children: Minnie, Ralph, Annie and Hazel. According to Annie, there was nothing exceptional about her birth except that she was breech. As she began to walk and talk, however, it was discovered that she had a speech impediment–a stutter–which everyone said was caused by being breech. “It has followed me all my life,” says Annie.

When Annie was just four years old, Howard decided to move the family to Nebraska, where he felt there was more opportunity. Annie grew up there and attended school through eighth grade. She begged her parents to let her attend high school as her older siblings had done. Against their better judgment, they agreed, but, as expected, Annie found it difficult to keep up due to her speech problem. The high school staff suggested that perhaps Annie would be better off attending a special boarding school back in Milwaukee, Wisconsin for handicapped, deaf and blind children, so, after much debate, Howard and Myrtle decided to send Annie there.

Annie worked hard at her new school and became a favorite of one of the teachers, who quickly realized that Annie did not belong there. He contacted the Gilman’s and suggested that Annie go and live with a family he knew in Chicago who would take care of her and send her to a normal public high school. The Gilman’s hesitantly agreed, and Annie then went to live with the Connelly’s, her adopted family, as she began to call them. During her four years in Chicago, Annie thrived, and her speech actually improved somewhat. Not only did she graduate, but she did so with honors.

After graduation, the Connelly’s, who had grown quite fond of Annie, encouraged her to stay with them and to try to get a job in Chicago, but Annie missed home too much, so she returned to Nebraska and enrolled in a one-year business school. Unfortunately, the move back home made her stutter grow worse again, and though she did well at business school academically, she decided to repeat the whole year over in an attempt to conquer her stutter.

Annie did not succeed in conquering her stutter, but she finally did graduate and then bravely attempted to find a job as a secretary. She was cruelly disappointed, however, to find that no one would hire her. She fell into a sort of depression and eventually decided to go back to Chicago. She stayed again for a time with the Connelly’s before she was able to get her own place. She gave up her dream of becoming a secretary and just took any odd job or factory position she could find.

This went on for many years until Annie was in her thirties. One night she went with friends to a party and was there introduced to a man by the name of Samuel Flemming, who worked as a machine shop operator. Samuel was the same age as Annie and had also never been married. The two of them quickly took a liking to each other and began dating and eventually married. Annie says that Samuel was the love of her life and that she adored him. Living with him helped her stutter immensely, Annie says, and it was because of him that she tried again to get a job as a secretary. She finally succeeded and got a job in a law firm on State Street. “It was the proudest day of my life,” she says.

Annie worked there for several years before getting up the courage to again apply for another secretarial position, this time at a building products company. She ended up getting the job, and she loved it. She worked there into her late sixties, and even after she retired, she would still come in as a temp if they needed her.

Annie and Samuel apparently had a wonderful life together. They didn’t have any children, but they belonged to many civic and church groups and had many hobbies. Before she met Samuel, Annie spent her free time reading and doing needlework, but after she married, she adopted several of Samuel’s hobbies. Thus she began helping him to rebuild old cars, his passion, and also to watch professional wrestling with him. Every year, they traveled to Florida where they would rent a little cottage and fish.

Annie and Samuel were a very happy couple until 1959 when Samuel died suddenly of a heart attack. Annie was devastated, but she eventually got over his death and continued on her own. All of her siblings had also already died, though she had many nieces and nephews back in Nebraska. So except for one niece, Emily, a daughter of her younger sister, Hazel, who also lived in the Chicago area, Annie was quite alone, as she had outlived most of her friends as well. As Annie grew older, Emily invited her aunt to come live with her, but each time, Annie refused, saying that she didn’t want to burden Emily and her family.

Annie lived independently until the early 1990’s when she made the decision to move to a nursing home. “It’s time,” Annie apparently said to Emily, who, at Annie’s request, helped her to choose a place. Annie is making a relatively smooth transition to her new home, though she is still a bit withdrawn. She enjoys bingo and has also taken an interest in the garden plots in the back of the home. “I’ve had a good life,” she says, “but now I’m ready to go to Samuel.” Incidentally, there is no sign of her stutter, perhaps proving once again that love always wins.

(Originally written: May 1992)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Overcame Her Stutter . . . appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 18, 2022

“Something About the Eyes”

Barbara Bianchi was born in Chicago on February 9, 1922 to Polish immigrants – Wislaw Gawrych and Olga Kobylinski. Olga worked long, long hours sewing table pads in a factory, and Wislaw worked as “a splitter,” a job he had done from the age thirteen, which consisted of “splitting” hides for jackets, shoes, gloves, etc. Apparently he could tell just by feeling a hide what it would be good for. Barbara says that she and her father were “buddies” and often went bowling or dancing together. When Barbara was ten years old, Wislaw and Olga had a second child, Wislaw, Jr., but the two siblings were never close.

Barbara attended high school until she was sixteen and then quit to work in a factory. There, she was befriended by a boy named Joey, who often persuaded Barbara to come to his baseball games. One day he introduced her to some of the players, including his friend, Samuel Lewkowicz, the team’s pitcher. It didn’t take Samuel long to ask Barbara out, and they quickly fell in love and married.

Samuel worked in a factory, and the young couple rented an apartment across the street from Barbara’s parents on Pulaski Avenue. They were apparently very much in love. Soon after their wedding, however, Samuel was drafted for the war. Barbara was already pregnant with their first child and panicked at the thought of giving birth without Samuel there. She pleaded with the draft board, who agreed to let Samuel stay until the baby, Samuel, Jr. was born. Not long afterwards, however, Samuel had to report to the navy and was stationed in Hawaii. Miraculously, he made it through the war unharmed, but on his way to pick up his discharge papers, he was tragically hit by a car and killed. Barbara, only twenty-three, had just given birth to their second child, Ruby, when the news came through.

Barbara spent the next four years struggling to make it on her social security checks with two children and no job. Her parents, Wislaw and Olga, who still lived across the street, were able to offer some help, but one day, Olga decided to take matters into her own hands. She brought home a young man, Paul Bianchi, whom she worked with at the factory and introduced him to Barbara. Apparently the two hit it off right away, and Paul Bianchi, just twenty-four at the time, came to see Barbara more and more until he finally worked up the courage to propose. They were married soon after. Barbara says they had “a happy life together,” and had six more children: Anthony, Mario, Howard, Albert, Luigi, and Martha. Eventually Paul became a purchasing agent for the University of Illinois Hospital, and Barbara remained a housewife, which she says she loved.

Although she had a happy life with Paul, two more tragic things occurred in Barbara’s life. The first was that her oldest son with Paul, Anthony, died in a fire at age thirty-two, leaving behind a wife and four children. Apparently, he predicted his death, telling Barbara for many years that he “wouldn’t live to see thirty-three.” The next tragedy entailed Ruby, Barbara’s second child with Samuel, who died when she was forty-five of spine cancer.

Ruby’s death was perhaps the hardest for Barbara to bear. She always had a special bond with Ruby that she could never quite explain—“something in the eyes” is how Barbara describes it. Perhaps it was that or that their bonding occurred at such a sad time in Barbara’s life, Ruby being born into the world just as Samuel was leaving it. Ruby was slow to learn to walk and talk and always had a myriad of health problems, and yet she was Barbara’s favorite. She never married and lived at home with Barbara and Paul. Barbara cried and grieved heavily during the last three years of Ruby’s life as she battled her cancer, and it took her many years to get over her death.

Despite the sorrows Barbara faced in her life, however, she has remained a positive, optimistic person. Her children describe her as “always up for a laugh and a joke.” Barbara herself says that she has always been “happy-go-lucky” and that her favorite saying is “tomorrow is another day.” She enjoys her seventeen grandchildren and seven great-grandchildren immensely and has always been very involved and active in their lives. Besides being a life-long member of the women’s club at St. Hedwig, she enjoys collecting dishes, gardening, baking and sewing (she always sewed all the kids’ clothes over the years.) When asked if she has done any traveling, her response was “just around the block.”

Recently, Barbara says she has begun “losing her balance” and experiencing small strokes. She fell a few months ago and laid on the floor for four hours before Paul found her. She is hoping to be able to go home, but, in her own optimistic character, says that if that is not possible, she will make the best of it and start a new life in the nursing home. She is making a very smooth transition to the home and welcomes meeting the other residents. Someone from her family usually brings Paul to see her every day.

(Originally written: April 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Something About the Eyes” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 10, 2022

From the Set of Gone With the Wind and Walt Disney Studios to an Internment Camp

Rosemary Tsukuda was born in Santa Cruz, California on March 10, 1913 to Japanese immigrants. Her father, Chihiro Hayashi, left Japan as a young man in search of adventure. His travels took him to Australia and then to California where he found work as a gardener and mechanic for a wealthy man in Santa Cruz. For a short time, Chihiro tried his luck in Florida, but he was unsuccessful in finding a job there and so returned to Santa Cruz.

Rosemary Tsukuda was born in Santa Cruz, California on March 10, 1913 to Japanese immigrants. Her father, Chihiro Hayashi, left Japan as a young man in search of adventure. His travels took him to Australia and then to California where he found work as a gardener and mechanic for a wealthy man in Santa Cruz. For a short time, Chihiro tried his luck in Florida, but he was unsuccessful in finding a job there and so returned to Santa Cruz.

Eventually, Chihiro’s thoughts turned to marriage, so he wrote to his family asking them to find him a wife. Excitedly they wrote and said that they had found a good match with a neighboring family. The girl’s name was Ayaka Ito, and she had always had a desire to see America and to be educated. Thus, Chihiro returned to Japan to marry her and then took her back to California with him. Together, Chihiro and Ayaka had ten children: Franklin, Robert, Estelle, Edward, Rosemary, Clement, Virginia, Norma, Walter and Leonard. Tragically, six of them died in childhood (Franklin, Robert, Estelle, Edward, Norma and Leonard). Thus, Rosemary, who had been born a middle child, then became the oldest.

Rosemary attended San Jose State University and from there went to art school in Los Angeles. She was employed by Walt Disney Studios and also worked on the set of Gone With the Wind. Her career and future indeed seemed very promising until World War II broke out and she found herself “rounded up” and taken to a “relocation center” with thousands of other Japanese-Americans. She was separated from her family and sent to the Amache camp in Colorado.

As she was boarding the bus that would take her there, however, Rosemary found a beautifully packed lunch on each of the seats, put there by the Quakers in an attempt to “love thy enemy.” Rosemary was very touched by this, and it sparked a life-long interest in the Quakers.

Rosemary spent three long years in the camp and there met her future husband, Katsuo Tsukuda. At age twenty-four, Katsuo had developed TB, which at that time had no cure. He spent three years suffering with TB and believing that he was going to die, but then miraculously recovered. Shortly afterwards, however, he, too, was sent to Amache, even though his brother was in the American air force.

At Amache, Katsuo had a special kind of compassion for the sick and eventually became a sort of chaplain-like figure, a role which shaped his decision to become a minister, just as his father was. He also decided to propose to Rosemary, whom he had gotten to know well and whom he guessed would be a good partner as the wife of a minister because she had perfect English.

When they were finally released, Rosemary and Katsuo moved to Chicago where his father had founded a church, and Katsuo wanted to help him. Katsuo says that before the war, there were only about 300 Japanese people in Chicago, but after the war when the Japanese were released from the internment camps, the number of rose to 30,000. He says he can still remember the radio advertisements put out by the government to entice business owners to hire Japanese-Americans because they were “well-educated, honest and industrious.”

Though many Japanese were bitter about their experience, Katsuo says that neither he nor Rosemary held any grudges. Katsuo says he understands why the Americans may have thought they were dangerous and doesn’t blame them for what they did. He felt very honored when the United States, years, later, publicly apologized and offered people restitution. Katsuo says that there were some positives that came out of the experience. For one thing, he met Rosemary and realized what his vocation in life was. Also, he says, it forced the Japanese people to spread out all across America instead of staying only on the coasts.

Katsuo says that once settled in Chicago, he threw himself into his ministry, and Rosemary became the breadwinner of the family, finding work as a successful commercial artist in Chicago. For whatever reason, they did not have any children. Rosemary ran their household and was responsible for all of the day-to-day things, as well as managing a career. She had very close friends and was a very honest and true person and a good judge of character, says Katsuo. She was fascinated by Latin culture, loved food and traveling and entertaining. She was very active in the Quaker church and also kept up a fifty-year correspondence with her fellow artists whom she had worked with on the set of Gone With The Wind.

When she was forty-five, Rosemary decided to switch careers and went back to school to become an occupational therapist. She worked for many years in that capacity at Evanston Hospital. Katsuo says that she was an extremely intelligent woman, but she didn’t like to show it. She was very modest and humble.

In the early 1990’s, Rosemary collapsed at home, and it is thought that she may have had a stroke. Upon finding her on the floor, Katsuo put her in bed and cared for her, rather than take her to the hospital. After six days, she began eating again, but her mental function was not what it had been. Since then it continued to get worse until 1996 when she suffered another stroke. This time, Katsuo called an ambulance, and Rosemary was eventually discharged to a nursing home.

Rosemary is making a fair transition to her new home, though she seems confused most of the time. She prefers to sit quietly in the day room beside Katsuo, who visits daily. Katsuo is quite beside himself and is having a hard time functioning alone at home. He is considering moving to the nursing home as well because he says he misses Rosemary and wants to take care of her. “We’ve been through a lot together, and I just can’t live without her,” he says.

(Originally written: August 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

SHOWING 22 COMMENTSThe post From the Set of Gone With the Wind and Walt Disney Studios to an Internment Camp appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

August 3, 2022

They Brought Her Home and Put Her in a Warm Oven

Felicia Billings says she began life at a mere two pounds on March 17, 1915. She was born prematurely in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to Irenka Jasinski, a Polish immigrant who worked as a seamstress, and Lutz Mueller, a German truck driver, one of six or eight children; Felicia isn’t sure.

Felicia Billings says she began life at a mere two pounds on March 17, 1915. She was born prematurely in Milwaukee, Wisconsin to Irenka Jasinski, a Polish immigrant who worked as a seamstress, and Lutz Mueller, a German truck driver, one of six or eight children; Felicia isn’t sure.

Apparently, the moment Felicia was born, barely alive at two pounds, her family rushed her across the back alley to St. Joseph’s to be baptized. She survived the baptism, however, so the family brought her back home and put her in the warm oven, her mother only supposedly removing her to feed her and occasionally place her on the seat of the rocking chair to be rocked. Though stories like this abound from that era and have been debunked as myths over the years, Felicia insists that hers is true. At any rate, she miraculously lived.

When she was three years old, the family moved to Chicago. Felicia went to school until eighth grade and then went to work as a nanny and a maid for a Jewish family. According to Felicia, the family treated her “beautifully—like one of their own.” It was Felicia’s job to care for the woman’s new baby and to be her personal maid. She was allowed one day off per week, which she usually spent at the roller rink. The family even offered to drive her there each week so that she wouldn’t have to take the bus.

Though she loved her job, Felicia eventually left to go work as a sales clerk at Goldblatts, where she met a young Jewish man, Stanley, and fell in love. They dated for several years and wanted to get married, but Stanley’s mother refused to allow it. They broke up, then, and Stanley married a young, wealthy Jewish girl. Felicia was happy for him and wished him well, despite her own heartache. She was unexpectedly vindicated one day, however, when Stanley’s mother came in to Goldblatts and admitted to Felicia that she had been wrong about her, but it was obviously too late. Felicia continued to get bits of news about Stanley over the years by writing letters to his sisters and says that she was never bitter about how it all turned out.

Eventually Felicia met another clerk at Goldblatts, Leonard Billings, a young man of English and Italian descent, whom she fell in love with and married at the Justice of the Peace. Fifty years later they had a big anniversary party and got re-married in the Catholic Church.

According to Felicia, she and Leonard had a wonderful life together. Leonard became a manager at Goldblatts and worked there for over fifty years. Felicia continued working there as well, even after their only child, Karen, was born. Felicia and Leonard went everywhere together, their only time apart being during WWII when Leonard enlisted and became a tank driver. Felicia reports that he was “a good soldier” and “came through it fine,” though he was injured in the heel and sent home.

Once back, he and Felicia picked right up where they left off and enjoyed going out to restaurants, bars and parties. Sometimes Leonard and Felicia would split up for the early part of the evening, each going to a friend’s house or a bar, before meeting up later to go somewhere together. They were actively involved in the American Legion for over thirty years and went to conferences all around the country. They had many, many friends.

Felicia continued to work at Goldblatts for most of her career and went out with her two work friends every Tuesday night for seven straight years before she retired at age 62. From there, she took a job at the American Medical Association in their accounting department and is proud of the fact that she learned to use a computer while there.

Sadly, Leonard died in his seventies of cancer after a long, painful fourteen months, which Felicia nursed him through. At 81, Felicia misses him still. She remained active after his death and is very proud of the fact that she learned how to use a computer. She had been living independently in an apartment above her daughter, Karen, but began falling and was eventually admitted to a nursing home. “Karen thinks I hate her for putting me here,” Felicia says. “I don’t hate her, but it is very hard to get used to.”

Though Felicia is finding the adjustment hard, she remains happy-go-lucky and says that “I enjoyed life tremendously!”

(Originally written: September 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post They Brought Her Home and Put Her in a Warm Oven appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

July 28, 2022

“She Hated Men With a Passion!”

Jadwiga Jurkiewicz was born on December 26, 1906 in Pennsylvania to Polish immigrants, but she later changed her name to Judy Jurka. She was one of six children, including two sets of twins, of which Judy was one. At age three, however, Judy’s twin died, possibly of the flu epidemic. Likewise, when Judy was six, her mother also died, leaving her father distraught and unable to care for the five remaining children. His sister came to live with them for a while, but she eventually had to return to her own family, leaving the father again confused and grieving.

Not knowing what to do, Judy’s father turned to his parish priest, who advised him to put the children in an orphanage. This was quite common in the early part of the last century. Many children in orphanages actually had living parents who for one reason or another couldn’t care for their children and so sent them away. Judy and her sisters were separated from her brothers and placed in two different facilities. Judy’s father visited often, but he, too, died young, making them true orphans.

When Judy turned sixteen, the nuns at the orphanage sent Judy to St. Mary of Nazareth School of Nursing in Chicago. Judy did well there and made many friends and eventually became a nurse. She had learned how to do fancy embroidery work at the orphanage and continued to do it as a hobby even after she left. She enjoyed it so much that she formed a sewing circle with some of the other nursing students at St. Mary, and it was at about this time that she met her life-long friend, Alice Shaw.

Alice, it seems, was the opposite of Judy, who was a very independent, tough, private person, perhaps because she needed to be to survive all those years in the orphanage. Alice was the more compassionate of the two friends, and she often acted as a sounding board to Judy’s rants. One of the things that Judy could not seem to “forgive and forget” was the fact that her sister had been raped by a priest in the orphanage and later suffered a mental breakdown because of it. She was sent away to a mental institution, and Judy never saw her again. Likewise, Judy’s younger brother was also later killed in a farm brawl somewhere in Nebraska, which Judy never understood, as she always described him as a very timid, gentle soul. Both of these things, and others, affected Judy very deeply, and she was never able to really to get over them. Judy became very attached to Alice and was devastated when Alice told her that she was getting married.

Judy “hated men with a passion” and begged Alice not to go through with the ceremony. Alice persevered, however, and was apparently very happy with her choice. She and her husband had a little girl, Margaret, to whom Judy became “Auntie Judy.” Despite her marriage, Alice remained Judy’s lifelong friend and often tried to help her move past some of her bitterness. Margaret reports that her “Aunt Judy” was a very kind and loving person to those in her immediate circle, but she could be very particular and stubborn and that she had a fiery temper.

Judy never married, but instead focused on her career as a private duty nurse and on traveling, which became a passion for her. She traveled the whole world and spent some of her winters in Florida, where she enjoyed walking on the beach and talking to local fishermen. She never had any hobbies besides sewing and did not belong to any church, saying that she did not believe in organized religion. Judy eventually retired at age 65 and has spent her retirement years going between Chicago and Florida.

Judy has been contentedly living alone until recently, when she was diagnosed with colon cancer. She was hospitalized for a time after a colostomy and was unable to care for herself at home, particularly as there was no one around to help her. Alice passed away in the late 1980’s, and Margaret had since moved out of state. Margaret is listed as her “next of kin,” however, so when the hospital discharge staff called her, she flew back to Chicago to help Judy choose a nursing home. She remains very devoted to Judy, and frequently comes back to visit her and telephones her weekly. She is Judy’s only support system.

Meanwhile, Judy is not making a smooth transition, even at Margaret’s urging. She refuses to participate in any activities or to meet any residents. She is extremely depressed and some days even refuses to get out of bed. She says she only wants to die. “My life is over. Look at me,” she frequently says to the staff. It is hoped that she might yet embrace her new life at the home with staff intervention, as well as encouragement from Margaret.

(Originally written: September 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “She Hated Men With a Passion!” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.