Michelle Cox's Blog, page 12

May 12, 2022

From Ukrainian Professor of Physics to Janitor

Sasha Pasternak was born on March 12, 1946 in Ukraine. His parents were Martyn Pasternak and Alberta Jelen. Jelen, Sasha reports, means “stag” in Polish, and he seems very proud of his mother’s name.

Sasha Pasternak was born on March 12, 1946 in Ukraine. His parents were Martyn Pasternak and Alberta Jelen. Jelen, Sasha reports, means “stag” in Polish, and he seems very proud of his mother’s name.

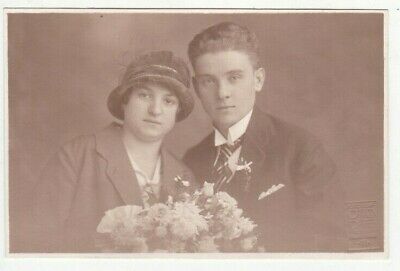

Martyn was a Ukrainian Jew, and Alberta was a Polish nurse living in Ukraine with an elderly woman she was hired to care for. As it happened, the elderly woman’s children and grandchildren often came to see her, and one day one of her grandson’s brought a friend along by the name of Martyn Pasternak. As soon as Martyn saw Alberta, he fell in love with her, and they married in 1928. Martyn worked as an economist, and Alberta continued working as a nurse until their first child, Anna, was born in 1932.

Fourteen years later, in 1946, a son was born – Sasha. Sasha attended high school and university, eventually becoming a professor of physics, with a specialty in medical radiation. He was on the chief of staff in this field, did extensive research, and gave lectures at the university in the evenings, enjoying his career immensely.

In 1969, when he was 23, he married the love of his life, Liliya. As it happened, however, he had been dating a different girl, Vira, shortly before he met Liliya. One night, he and Vira went to a friend’s apartment to celebrate Vira’s birthday. At the impromptu party, Sasha was introduced to his friend’s date, Liliya, and instantly fell in love with her, perhaps in the same way his father, Martyn, had fallen in love with Alberta. Ten days after Vira’s birthday party, Sasha married Liliya in a quiet service.

Sasha and Liliya, who worked as a language teacher, made a happy life for themselves in Ukraine and had two sons: Ivan and Denys. Sasha says he left the Communists to themselves and lived his own life. He felt he had a pretty good salary, a great job, a nice family and a nice apartment. When Communism fell, however, his life began to fall apart. His salary shrank to almost nothing and his sons, just leaving university, had no job prospects. Seeing the situation in the Ukraine as hopeless, Sasha decided to move the family to America and arrived in Chicago in 1994 with Ivan and his wife and daughter; Denys; and Liliya’s parents. And while there proved to be much more opportunity for their sons, Sasha and Liliya’s prospects worsened. Sasha gave up his brilliant career in research to become a janitor, and Liliya found a job at the counter of Lord and Taylor.

After about a year in America, the powers that be at Evanston Hospital where Sasha worked as a janitor heard of his background in the Ukraine and offered to send him through 14 months of training in medical radiation in exchange for him to continue working as a janitor as a volunteer. Sasha desperately wanted to take the offer, but eventually declined it, knowing that they could not exist for that period of time without his salary. For one thing, shortly after their arrival in America, Liliya’s parents began to have a myriad of health problems. Her father had to have a lung operation and his leg amputated, which required extensive hospitalization. In order to visit him every day, Liliya’s mother had to take three buses to get to the hospital, and eventually the stress got to her. She had a heart attack and then a series of strokes and falls before she finally died.

Sasha eventually was offered a more humble position of lab technician. It did bring in a little more money than he had been making as a janitor, but the family still struggled because Liliya had been forced to quit her job to take care of her parents when they were ill and dying. As luck would have it, things got even worse for the Pasternak’s. In October of 1996, just as Liliya was getting over the death of her father, Sasha was hit by a car. He spent eighteen days in the hospital before he was transferred to a nursing home to more fully recover. Upon his admission, he had a lot of anxiety and found it difficult to lie in bed all day. He has since begun to be up and about more and looks forward to Liliya and his sons coming to visit each day. He is eager to get home and back to work, he frequently repeats, though he worries that his job will be given to someone else. His boss, he says, has promised to hold his job, but, Sasha says, “I am a pessimist at heart. I wait and see.”

(Originally written: October 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post From Ukrainian Professor of Physics to Janitor appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 5, 2022

“She Could Move Mountains”

Lidka Klimek was born on March 13, 1900—one of twelve children—in what is now Radziechow, Poland. Not much is known of her parents, her childhood, or her early life with her husband, Edmund Klimek and their four children: Marta, Olga, Regina and Fabian. Lidka’s story, it seems, begins in 1941 when the Russians invaded their village in what was then a part of Germany.

Lidka Klimek was born on March 13, 1900—one of twelve children—in what is now Radziechow, Poland. Not much is known of her parents, her childhood, or her early life with her husband, Edmund Klimek and their four children: Marta, Olga, Regina and Fabian. Lidka’s story, it seems, begins in 1941 when the Russians invaded their village in what was then a part of Germany.

Like most of the people in the village, Lidka and Edmund and their children were displaced and sent on a cattle train to Siberia. It is unclear why, but somehow on the journey, Edmund died, leaving Lidka alone with the children. Once in Siberia, she was forced to cut trees for which she was given a daily ticket for bread and water. She took her children with her into the forest to help her and to forage for any extra food they could find. The Klimek’s spent the rest of the war this way, and when it finally ended, they were again put on a train, this time bound for refugee camps in what is now Pakistan and Afghanistan. From there they went to a camp in India under English control and remained there until after India was liberated from the British in 1947. From India, Lidka took the family to London, where they stayed for a number of years.

At some point in this tragedy, Lidka’s oldest daughter, Marta, escaped one of their internments, making her way back to Poland to join the underground. She drove ammunition trucks for the army in Poland and then found her way to Italy and finally the United States after the war ended. She and her husband were able to get a sponsor in America through a distant relative of her husband’s. Finally, in 1952, Marta convinced Lidka and the rest of the family to come to Chicago so that they could all be together.

Lidka finally agreed and made the journey with her remaining three children, all of whom had spouses and children of their own by now. They landed in New York first, where they stayed for several months, though they hated every minute of it. They eventually made the journey to Chicago where they were finally reunited with Marta, meeting her husband and children for the first time. From that point, they all worked and saved money until they could buy a house big enough for them all to live in.

A pattern quickly developed in which the adults all went out to work each day while Lidka stayed home and watched all of the grandchildren, teaching them Polish and stories from the past as well as how to respect the country and culture they now found themselves in. She was always dispensing little bits of wisdom, her family says of her. Besides tending to the children, Lidka also did all of the cooking, the cleaning, the sewing, the baking, the gardening, and volunteered at church. At the holidays, their house was always packed with people and food, music and laughter. One of Lidka’s daughters, Olga, recounts that her mother was the most positive person she ever knew—so active and truly “full of life.” Lidka was always ready for anything, Olga says. “She was one of those people who could truly move mountains.” All of her children report that despite what she had been through, Lidka remained a very positive, loving, warm, caring person. “She was wonderful,” they all agree.

Lidka remained at home with her family until 1995, at which point they admitted her to a nursing home. She was 96 at the time. Apparently, despite the family’s best efforts, Lidka was having more and more difficulty doing even the most simple things and was constantly falling, wandering and confused. Lidka’s doctor advised putting her in a nursing home before she seriously injured herself, and, after much debate, the family finally agreed. Someone from the family comes daily to sit with her, though Lidka is for the most part uncommunicative. She will sit during an activity at the home, but she does not usually participate. Likewise, she does not seem to enjoy speaking with other Polish residents to whom she is introduced, but simply sits quietly, whispering “pray for me” and “pray for us” over and over.

(Originally written: May 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

SHOWING 7 COMMENTSThe post “She Could Move Mountains” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 28, 2022

He Promised to Take Her Dancing Every Week!

Clara Mae Hansen was born on May 14, 1902 in Adrian, Michigan to Henry Engelskirchen and Katherine Burkhart. Henry was of German descent but was born in Mendota, Illinois, and Katherine was originally from Orland, Il. Henry apparently had a hard life. When he was ten years old, his stepmother made him quit school to go work in a brickyard. Eventually, he ended up working as a superintendent in a piano factory in Mendota. He met and married Katherine Burkhart, and together they had nine children: Arthur, Henry, Walter (who died at eleven months), Harvey, Clara, Alma, Willard, Howard and Florence.

Clara Mae Hansen was born on May 14, 1902 in Adrian, Michigan to Henry Engelskirchen and Katherine Burkhart. Henry was of German descent but was born in Mendota, Illinois, and Katherine was originally from Orland, Il. Henry apparently had a hard life. When he was ten years old, his stepmother made him quit school to go work in a brickyard. Eventually, he ended up working as a superintendent in a piano factory in Mendota. He met and married Katherine Burkhart, and together they had nine children: Arthur, Henry, Walter (who died at eleven months), Harvey, Clara, Alma, Willard, Howard and Florence.

When the piano factory closed down in Mendota, the family moved to Steger, Illinois, where there was another piano factory. They remained there only five years, however, as they did not like Steger and decided to try their luck in Chicago. Clara was nine when they moved to the big city.

The Engelskirchen family settled in the northwest part of the city and managed to make a living as best they could. Tragically, however, Katherine died in August of 1916, just five years after moving there. According to Clara, the family was attending the funeral of a friend on the outskirts of the city, and as they walked along in the funeral procession in the hot August sun, Katherine became overwhelmed with thirst. They happened to pass an old, deserted farmhouse near the cemetery, and when Katherine spotted a well in the front yard of the farmhouse, she broke off from the procession to get a drink from it. Alarmed, Henry tried to stop her, warning her about drinking from a well that had not been used for such a long period of time. Katherine ignored him, however, and drank from it anyway. As a result, she came down with typhoid and eventually died.

At the time of her mother’s death, Clara was fourteen and, as the oldest girl in the family, was made to stay home and keep house and care for the children. Her youngest sibling, Florence, was only four. Clara, who had been so looking forward to going to high school, had to quit after only attending for two days. She was utterly crushed, as it had been her dream to go to school beyond eighth grade. She begged her father to hire someone to come in and take care of things instead of her, but he claimed he couldn’t find anyone who would take on such a big family and that he couldn’t afford it anyway.

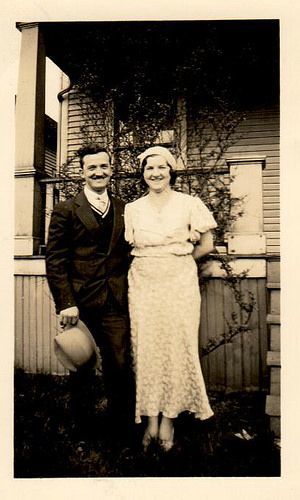

So Clara stayed home for two years, and when she was sixteen, Henry was finally able to find someone to hire on a part-time basis. By then, however, it was too late for Clara to attend high school, so she got a job at Carson’s Wholesale, which she ended up really enjoying. There, she met a friend, Florence, who was always begging her to come with her on a Saturday or a Sunday night to the nearby Mable Theatre on Elston and Irving Park Road (later becoming the Revue Theatre in 1934), which, Florence claimed, had the best vaudeville acts around. After much refusing, Clara finally agreed to go with her one night and found herself laughing as much as Florence. They spent the walk home talking about which had been their favorite acts and laughing all over again. Eventually, however, they noticed that two young men were following behind them. When the girls finally reached Clara’s house, one of the boys, Arthur Phillip Hansen, asked if he could have Clara’s telephone number. Clara lied and said they didn’t have a telephone, but Florence spoke up and said that “they do too have a telephone!” and promptly gave Clara’s number to the hopeful Arthur.

As it turned out, Clara rather liked Arthur, and they dated for two years before Arthur worked up the courage to propose. Clara was hesitant to accept him because she didn’t want to give up going to dances. Although she liked Arthur well enough, her real love in life was dancing. Arthur, for his part, didn’t dance, but he swore to her that if she married him he would drive her and her girlfriends to the dance halls every week. Clara agreed, then, and was married at eighteen, which she later said, “was too young!” and that it was “a rotten trick!” as no sooner was she married but she got pregnant, and that was the natural end of her dancing days.

Arthur and Clara seemed happy enough, however, and had three sons: Robert, Richard and Jack. They lived in the same apartment on Kasson Avenue for 29 years. When they first met, Arthur had a job as a roofer, but after three close calls, he took up carpentry instead and worked at that for the rest of his working life. Clara’s father, Henry, died at age 71 the night Pearl Harbor was bombed. Clara does not remember of what. Arthur died at home in 1990, age 93, with Clara by his side.

Since Arthur’s death, Clara has steadily gotten worse on her feet and has fallen several times. All three sons are themselves retired and battling health problems and are therefore unable to care for Clara. They have all urged her over the past few years to go to a nursing home, but she has continually refused. Recently, however, they were able to get her to go to a nursing home on “a trial basis.” Clara therefore believes that she will soon be returning home, though her sons confess that this is probably not a realistic option. Clara, despite wanting to go home, is making friends and participates in many of the offered activities. “All of my friends have died,” she says and enjoys smoking and meeting other residents. Her mind is still extremely sharp, and she can remember many stories of the past. She likes the facility very much, she says, but she is just “biding my time” until she can go home.

(Originally written: December 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post He Promised to Take Her Dancing Every Week! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 21, 2022

Three Ladies of Italian Descent in Chicago

Mafalda Jedynak was born in Chicago on March 15, 1909 to Mario and Luisa Scarsi, both of whom were Italian immigrants. Mafalda says that there were five children in the family, though she thinks there might have been more that died. The only siblings she can remember are Maria, Angelo, Natalia, and Carlo.

Mafalda Jedynak was born in Chicago on March 15, 1909 to Mario and Luisa Scarsi, both of whom were Italian immigrants. Mafalda says that there were five children in the family, though she thinks there might have been more that died. The only siblings she can remember are Maria, Angelo, Natalia, and Carlo.

Mafalda went to school until eighth grade and then got a job doing office work. Most of her life, she worked two jobs and alternated between factory work and cleaning offices at night. When she was seventeen, she met and married Thomas Jedynak, an immigrant from Poland who worked in various factories around the city. The following year she gave birth to their only child, Thomas. Mafalda got pregnant many times throughout her marriage, but miscarried each time.

Thomas grew into adulthood, but he was tragically killed in World War II, leaving behind a wife, Cynthia, who was pregnant with their first child, Margaret. After Thomas was killed, however, Cynthia went to live with her parents and had very little to do with Mafalda and Thomas after that. She eventually remarried, and Mafalda always felt bad that they never really got to know their only grandchild.

In the late 1970’s, Thomas passed away from prostate cancer, and as far as anyone knows, Mafalda continued to work and live alone. Her neighbors describe her as “hard-working, kind, dedicated and caring.”

By the time the 1990’s rolled around, Mafalda says her health began to decline, and she decided to start investigating nursing homes. While touring one, she fell and broke her arm and had to be hospitalized. When she was ready to be discharged, she decided to admit herself to the one where she had fallen and broken her arm, as she saw this as a sign from God that this was where she was supposed to go.

Despite being somewhat limited by her broken arm, Mafalda seems to be making a smooth transition to her new home. The staff have been able to locate Cynthia and Margaret, who are living in the Chicago suburbs, but neither of them are interested in Mafalda’s care or well-being, saying that they are not responsible for her.

Mafalda seems to be trying to make the best of the situation despite occasionally saying, “there’s no one left but me.” She attempts to strike up conversations with other residents and willingly joins in activities.

***

Paulette Lopez was born in Chicago on November 30, 1922 to Italian immigrants, David and Maria Ungaro. David and Maria met and married in Italy and decided while their family was still young to come to America. They settled in the Chicago, where David found janitorial jobs on and off, but he often went for long periods of time without working. Paulette was the one who worked constantly as a waitress, despite having five children: Eduardo, Paulette, Philip, Ronaldo and David, Jr.

Paulette Lopez was born in Chicago on November 30, 1922 to Italian immigrants, David and Maria Ungaro. David and Maria met and married in Italy and decided while their family was still young to come to America. They settled in the Chicago, where David found janitorial jobs on and off, but he often went for long periods of time without working. Paulette was the one who worked constantly as a waitress, despite having five children: Eduardo, Paulette, Philip, Ronaldo and David, Jr.

Paulette attended two years of high school in Chicago and then began working in various factories and restaurants all over the city. Through a friend, she was introduced to Alfredo Lopez, whose parents had immigrated from Cuba. Alfredo was six years older than Paulette, but they started dating anyway and eventually married when Paulette was twenty-two. Alfredo worked for the railroad, and Paulette says he was a very gentle, good man. They eventually saved enough to buy their own little house on Barry Avenue and had two children: Cal and Betsy.

Paulette says they had a good marriage and that they enjoyed being home together. Paulette did all the housework, and Alfredo did all of the gardening. They were also very active in their parish, St. Ferdinand. Cal and Betsy eventually married and moved out, though they remained close by, so that Paulette and Alfredo have been able to see their five grandchildren grow up. Paulette says that she used to enjoy music and reading but that her main hobby now is smoking.

Sadly, Alfredo passed away in March of emphysema, and since that time, Paulette has sunk into a depression. By November, her depression had deepened so much, despite the activity of her children and grandchildren, that she took an overdose of medication, which has been interpreted as a suicide attempt. Upon her discharge, she was taken to a nursing home, though both Cal and Betsy are still very upset by her placement. They both offered to take her into their homes, but the social service staff convinced them that this would be a better place for Paulette where she could be more social.

Paulette seems to be making a relatively smooth transition, though she appears to be nervous much of the time and spends a lot of time in the smoking lounge. She is pleasant and agreeable but says she doesn’t ever think she is going to get used to life without Alfredo.

***

Tecla Bautista was born on February 28, 1911 in Lucca, Italy to Ennio and Vanna Zini. She attended school until eighth grade and then got a job in a button factory. She says she came from a family of ten children, but she cannot remember all of their names. When she was still just a teenager, her parents sent her and her sister, Agostina, to live with an aunt in Chicago. Both Tecla and Agostina found work as maids for rich families on the south side of Chicago until Tecla met a man by the name of Cornelio Bautista, who was originally from Mexico. Cornelio worked for the postal system and after dating for only a couple of months, they got married.

Tecla Bautista was born on February 28, 1911 in Lucca, Italy to Ennio and Vanna Zini. She attended school until eighth grade and then got a job in a button factory. She says she came from a family of ten children, but she cannot remember all of their names. When she was still just a teenager, her parents sent her and her sister, Agostina, to live with an aunt in Chicago. Both Tecla and Agostina found work as maids for rich families on the south side of Chicago until Tecla met a man by the name of Cornelio Bautista, who was originally from Mexico. Cornelio worked for the postal system and after dating for only a couple of months, they got married.

Tecla quit her job as a maid and stayed home to keep house for Cornelio and their eventual two sons, Ernesto and Gabriel. Unfortunately, however, Cornelio died young at age 43 of a heart attack, so Tecla went back to work and got a job at the Moody Bible Institute as a cleaner. She was able to raise her sons, who both managed to graduate from high school and find jobs in the city. Ernesto married a young woman by the name of Isabelle Fernandez and had three children. Gabriel remained at home with Tecla, helping her over the years as she grew older.

Gabriel says that his mother was always a nervous person and didn’t have many hobbies besides going to church. When she was diagnosed with cancer last year, it was very devastating to the whole family, but particularly to Gabriel. Tecla has undergone some chemotherapy, but she has not reacted well to it. Recently, she decided to stop treatments and accept her terminal prognosis. Her health then declined so much and she became so frail that Gabriel could no longer care for her at home. At the advice of a social worker, he recently admitted her to a nursing home.

Tecla is aware that she doesn’t have much longer to live, but she says she is at peace and ready to die. She spends most of her time sitting in her room or in a corner of the day room waiting for her sons to visit her. Gabriel appears to be more distraught than Tecla and prays with her when he comes to visit each day. Tecla says she draws much strength from this. She is a very gentle, quiet woman, and both sons say that she has a heart of gold.

(Originally written: February 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Three Ladies of Italian Descent in Chicago appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 14, 2022

The Unstoppable Boris Jankovic

Boris Jankovic was born on June 24, 1906 in Chicago to Andrej Jankovic and Dora Babic, both immigrants from Yugoslavia, though they grew up on neighboring farms in Ohio. When she was seventeen, Dora married a man by the name William Utzmann and had a baby boy, Adam, the following year. When Adam was just a year old, however, William was killed in a farm accident. Dora then turned to her childhood friend, Andrej, and they soon became engaged to be married.

After they were married, Andrej worked on his father’s farm and also as a hired hand, and Dora stayed at home to care for Adam and four more children that came along: Boris, Natalia, Dusan, and Jasna. At some point, however, Andrej and Dora made the decision to move to Chicago to try to make a better living. Andrej found work as a janitor at a college, and Dora began cleaning offices at night.

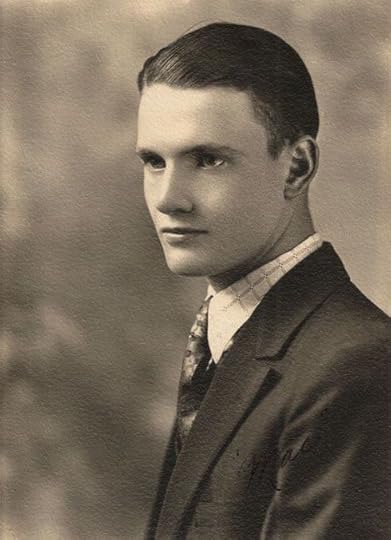

Boris went through eighth grade in Ohio, and when the family moved to Chicago, he got a job at a furniture store loading trucks. He saved every penny, and after eight years, he had enough to buy a little fruit and vegetable market on Division. His little venture became relatively successful, and even his father, Andrej, sometimes worked for him.

When Boris was twenty-eight, he became acquainted with one of his regular customers, a young woman by the name of Nancy Horvat, who came to the market almost daily, as she was one of twelve siblings and they went through groceries very quickly. Boris began to look forward to Nancy coming in each day and finally worked up the courage to ask her out. Nancy, who was very shy, at first said no. Boris persisted, however, and finally persuaded her to go to see a movie with him. The two of them hit it off right away, and she and Boris began dating. Eventually, Boris proposed to her, but Nancy turned him down, saying that she needed to stay home and care for her mother, who was blind and partially paralyzed, as well as her chronically ill sister.

Boris considered the situation and decided to proceed anyway. He was quite smitten with Nancy and wanted her to be his wife. His solution was for him to move in with Nancy’s family so that Nancy could still take care of her mother and sister. Nancy’s father had already passed away and most of her siblings had already moved out, so it was a solution that satisfied everyone. Boris continued working ceaselessly at the market, and Nancy stayed home to care for the invalids and for her and Boris’s two little girls, Karen and Francine.

Twenty years passed, and eventually Nancy’s sister and mother both died, and the girls married and moved out. Boris decided he needed a change as well and sold his market in 1952 to a friend. He wanted to get into the emerging food industry and therefore took a job working at “a drive-in burger joint” while he went to school at night to learn bartending.

Two years later, he put his experience and schooling to use when he bought the Lisle Lounge in Lisle, Illinois in partnership with his sister, Natalia, and her husband, Len. Boris and Len worked the bar, and Natalia and Nancy ran the kitchen. Boris and Nancy sold their house in the city and moved to Lisle to be closer to the restaurant. The Lisle Lounge was apparently a big success. Boris worked ceaselessly, just as he had at the market, and therefore had little time for hobbies except a bit of gardening and listening to music. Occasionally, he and Nancy would go dancing, which they both enjoyed. Boris loved working at the restaurant, and it soon developed a faithful crowd. Boris had dreams of expanding it, but his partner, Len, was against it. What began as a discussion eventually evolved into arguments and then finally, a huge fight. Unable to come to an agreement about the restaurant’s future, they decided sadly to sell it. Boris tried to buy out Natalia and Len’s share, but he couldn’t come up with the needed money, and Len wouldn’t budge.

After they sold the Lisle Lounge, Boris got a job as a bartender at a new restaurant in Naperville called the Willoway Manor. He very much enjoyed working there, as he bartended at night and did the restaurant’s yard work during the day. Eventually, it closed, however, so he then got a job bartending at Sharko’s in Lisle. He remained there until he was seventy-two when he finally retired.

At that point, Boris and Nancy decided to travel. They went to Europe and twice to New Zealand. They also made several trips to Arizona to visit their daughter, Karen, and her family, and to Hawaii, where their daughter, Francine, was living.

Sadly, in 1986, Nancy was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and died within a month. It was a terrible blow to Boris, who could barely remember life without her. She had been his best friend. He began drinking heavily, and his own health began to decline. Francine and Karen both agreed that something needed to be done, but they disagreed as to what. Francine was of the opinion that Boris should go to a nursing home, but Karen was adamant that he would never survive in such a place. Ultimately, Karen won out and flew to Chicago to bring her father back to Arizona to live with her.

Unfortunately, two years after her mother died, Karen’s husband was also diagnosed with cancer, and she found it almost impossible to care for both him and Boris. Boris, it seems, did not particularly like Arizona, anyway, and wanted to go back to Chicago. Reluctantly, then, Karen made the arrangements for him to be admitted to the Golden Age Retirement home in Lyons, Illinois.

Boris apparently really enjoyed the Golden Age and made a smooth transition to life there. Initially, he joined many activities and made several friends. After six months, however, he became particularly close with a woman named Ida Kovacevic. Ida soon became his constant companion, which, at first, Boris enjoyed. She became very possessive of him, though, as time went on, and isolated him from other people as much as she could. The staff tried to intervene, but they were not completely successful in getting Boris to branch out. Boris stopped going to activities and social gatherings to spend all of his time with Ida, and his budding new friendships with other residents died off. This went on for about two or three years, so when Ida suddenly passed away, Boris was left with very few social supports and grew extremely depressed. For a time, he refused to join any activities, and his appetite was seriously affected.

Right at that time, the ownership of the Golden Age changed hands, and the new owners decided to make it a more independent living facility and made arrangements to transfer all residents who needed assistance to other facilities. Boris unfortunately fell into this category. For awhile, several members of the staff, who really loved Boris and wanted him to stay, tried “covering” for him as much as they could, but it soon became obvious that Boris could not exist independently.

Thus, Karen was again contacted, and the decision was made to transfer Boris to the Bohemian Home for the Aged in the city, where it is hoped he will make a smooth transition and that he will enjoy being in a Slavic environment. So far, Boris is happy that he is served a pilsner every night with his dinner and enjoys hearing old Bohemian songs, some of which he is familiar with from his childhood. He is a very sweet man and seems eager to start all over yet again.

(Originally written: February 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Unstoppable Boris Jankovic appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 7, 2022

The Maid, the Asylum, and the Old Cubs Field

Agnes Faraldo was born on April 11, 1917 in Chicago to Feodor Ciesielski and Vera Bergmann. Both Feodor and Vera were born in Chicago, though Feodor’s family came from Poland and Vera’s from Germany. Feodor was one of fourteen children and had little schooling. He worked as an usher in a movie theater, which is where he met Vera, the concessions girl. Years and years later, Agnes discovered that when her parents got married, Vera was already seven months pregnant with her!

After they got married, Feodor quit his job at the movie theater and got a job as an electrician. They moved from apartment to apartment in the Milwaukee, Belmont and Western area of the city, and Vera had three more children: Polly, Bud, and Wilson. As time went on, Feodor began to drink heavily and became an alcoholic. He and Vera’s marriage, never a happy one, as it turned out, disintegrated completely when Vera went to live with another man by the name of Oscar Schaffer and took the children with her.

Any hopes that Agnes had that their life would be better with Oscar were quickly dashed. She quickly grew to hate Oscar, though she does not say why, but her mother seemed content to stay with him. Vera lived with him for twelve years before finally getting married to him. Feodor, meanwhile, later died in the TB ward of Cook County Hospital in 1942, a “broken-down alcoholic.”

Agnes quit school after seventh grade to get a job and desperately wanted to move out on her own after the family moved in with Oscar. Vera refused to let her, though, until she turned eighteen. When her eighteenth birthday finally came, she left and took a job as a maid for a wealthy family, which provided room and board. She stayed away from the family for almost a year before being persuaded by her sister, Polly, to come home to help celebrate their brother, Wilson’s, graduation. Agnes agreed and at the party was introduced to Polly’s boyfriend, a man by the name of Vince Faraldo, whom she was instantly attracted to. When Vince asked her out the very next day, Agnes agreed, but was wracked with guilt that she was betraying Polly.

Vince and Agnes really hit it off, but Agnes worried about what kind of man would switch his affections so easily, especially between sisters. Vince managed to convince her, though, that he had only recently met Polly and that she was more of a friend than anything else. When Agnes finally worked up the courage to tell Polly how she felt about Vince, Polly didn’t seem to mind at all. “He’s not that great. You can have him!” Polly supposedly told her.

With Polly’s blessing, then, the young couple began dating and married in 1939. Agnes quit her job as a maid and became a housewife. When they met, Vince had a job delivering coal and ice, but after they got married, he began working for the B & O Railroad and finally ended up as a cement mason. Their first baby, Anthony, was born in 1940, and two years later, Rosamund, was born. When the World War II broke out shortly thereafter, Agnes and Vince made a conscious decision not to have any more children. Fortunately, Vince did not have to serve in the army because he had stomach ulcers.

Agnes and Vince first lived in an apartment near 12th and Taylor, close to where Vera lived and a year later moved to May St. and Polk, which was where Anthony was born. From there they moved to Hermitage and Taylor, where they remained for eight years until they eventually had to vacate their apartment because the University of Illinois Hospital was buying up land in the area to expand their campus.

Agnes has an interesting story about that area of the city and enjoys sharing it with anyone willing to listen. According to her, in 1917, the same hospital bought up the nearby, vacated Chicago Cubs ballpark, also known as West Side Park, which was located at Polk and Wolcott and which was where the Cubs won two World Series championships. At the time that it was still being used as a ball park, however, there happened to be an insane asylum located just past the left field fence. Agnes says that it is common knowledge that during the games, the inmates of the asylum used to scream crazy things out of the windows, which is supposedly where the phrase “that came out of left field” originated!

At any rate, Agnes and Vince were thus forced to leave the area and moved north to Division Street, just across from Humboldt Park , where they stayed in a friend’s basement apartment until they could find something better. Agnes says that it was hard to find a place in those days and that many did not like children. They eventually did find a place down the street on Division and stayed there for fifteen years. Then they moved to Drake and Belmont and stayed there for another twenty years until Vince died of cancer in 1984.

After Vince passed away, Agnes lived on her own until her eyesight began to get bad. Her daughter, Rosamund, persuaded her to come and live with her in Antioch, Illinois, very far north of the city. Agnes stayed there for two years and enjoyed being with family, but in the end, she missed the city too much and decided to go back, much to the family’s dismay. They helped her, however, to move into a basement apartment on Montrose, where she remained for one year before moving to Forest Preserve Drive.

Needless to say, Agnes was a very independent woman and was able to care for herself relatively well despite her failing eyesight. When she was nearly hit by a car when attempting to cross the street, however, she began to become frightened of leaving her apartment at all. She became depressed and reclusive, so Rosamund and Anthony decided to intervene. Anthony told her that his mother-in-law had just gone to live in a nursing home on the NW side and that she really liked it. Curious, Agnes agreed to visit it and also really liked what she saw. She agreed that it would be the best, safest place for her and so, one more time, perhaps her last, she moved.

Agnes is adjusting very well to her new home and is very eager to meet people and to help out all she can. Currently she enjoys helping the staff fold laundry and has joined many activities. She loves smoking with her fellow residents in the smoking lounge, and has a wonderful sense of humor. She says that her hobby used to be embroidery, but since she can no longer do that because of her eyes, she is hoping that she can find some new hobbies at the home! Agnes has a real zest for life and is a very fun person to converse with and be around. She has quickly become a favorite among her fellow residents.

(Originally written: July 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Maid, the Asylum, and the Old Cubs Field appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 31, 2022

Three Ladies of German Descent in Chicago

Imogene Ferris was born on April 12, 1903 in Chicago to Xaver and Elena Bergmann, both of whom emigrated from Germany as children. Their families were neighbors in Chicago, and Xaver and Elena often played together in the streets. When they grew up, they married and had six children: Thomas, Imogene, Roberta, Caroline, Estelle and Olga.

Imogene Ferris was born on April 12, 1903 in Chicago to Xaver and Elena Bergmann, both of whom emigrated from Germany as children. Their families were neighbors in Chicago, and Xaver and Elena often played together in the streets. When they grew up, they married and had six children: Thomas, Imogene, Roberta, Caroline, Estelle and Olga.

Imogene graduated from eighth grade and went to two years of high school before quitting to get a job as a typist. She worked for various companies until she got a position as a billing clerk for the railroad, a job she held for thirty-five years.

When Imogene was just eighteen years old, she met and married a man by the name of Clarence Higgins, who was several years her senior. It didn’t work out, however, and the two of them divorced before the first year was even over. After that, Imogene moved into the upstairs apartment of her parents’ two-flat and cared for them until they died. She loved dancing at the Aragon, playing the piano, crocheting and could fix almost anything. She had a knowledge of many different things and was a great conversationalist.

Just before Imogene retired at age sixty-five, she met a man by the name of Martin Ferris, whom she fell in love with and married. The two of them traveled around the country, staying in different places for extended periods of time, including Florida, Missouri, Kentucky and Tennessee. They were together for about ten years before Martin passed away. After that, Imogene returned to Chicago to live near her sisters. Her brother, Thomas, had died many years earlier.

When Imogene had bypass surgery in the early 1990s, however, she was admitted to a nursing home to recover. It was at first thought that she might return to her apartment, but she eventually came to the conclusion that it might be too difficult to live alone and that her sisters were not in a position to care for her, either.

Imogene made a good transition to life in a nursing home. She had a relatively positive outlook, though at times she was forgetful and confused. She enjoyed going to all of the craft activities, as well as bingo if someone escorted her.

***

Eula Gallagher was born on December 22, 1896 in Chicago to Wilhelm and Friede Sauer. It is unknown when Wilhelm and Friede arrived in Chicago or what type of work Wilhelm did. Friede was a housewife and cared for their two children: Eula and Randolph.

Eula Gallagher was born on December 22, 1896 in Chicago to Wilhelm and Friede Sauer. It is unknown when Wilhelm and Friede arrived in Chicago or what type of work Wilhelm did. Friede was a housewife and cared for their two children: Eula and Randolph.

Eula attended high school and afterwards got a job in an accounting office where she met and married Junior Gallagher. According to Eula’s lifelong friend and neighbor, Annie Weitz, Eula and Junior were a lovely couple. They always acted as though they were sweethearts their whole married life and seemed to be deeply in love. Annie says that they were both very kind, gentle, sweet people. When not at work, they enjoyed pottering around the house and the garden, playing Bridge and doing a little traveling. Sadly, Annie says, they had no children of their own, but they were a beloved “aunt and uncle” to her four children over the years and delighted in helping to care for them whenever needed.

In the early 1970’s, Junior passed away, and then, not many months later, Eula’s brother, Randolph, passed away, as well. Eula remained in the same house and continued on as best she could, relying on her friend, Annie, more and more as the years went on. Her health continued to decline, however. She developed breathing problems and then began to show signs of Alzheimer’s. She was often found wandering the neighborhood, and Annie began to notice that she was mismatching her clothes and wearing several layers, which, she says, was odd, as Eula was always a “great dresser.”

When she was hospitalized due to what Annie thought might be a heart attack, her doctor insisted that she be admitted to a nursing home. Annie was listed as the contact person and helped to pack up some of Eula’s things to bring to the nursing home for her. At times, Eula recognized Annie, but at other times she did not. Overall, Eula seemed very content with her placement and enjoyed being in the day room with other people. The move was hard on Annie, however, who frequently cried when she visited, especially the times when Eula didn’t recognize her. “We were the very best of friends,” she would often say. “I miss her.”

***

Irma Koch was born on November 5, 1918 in Chicago to Adolph and Dorothea Koch. Both Adolph and Dorothea were German immigrants who came to America at the turn of the century. Adolph found work in a foundry, and Dorothea cared for their four children: Arthur, Louis, Irma, and Mary.

Irma Koch was born on November 5, 1918 in Chicago to Adolph and Dorothea Koch. Both Adolph and Dorothea were German immigrants who came to America at the turn of the century. Adolph found work in a foundry, and Dorothea cared for their four children: Arthur, Louis, Irma, and Mary.

Irma went to school until eighth grade and then quit to take a job in a sausage factory. Irma’s sister Mary says that Irma was like any other girl her age and enjoyed music and going to dances. She had a lot of friends and was a very hard worker. Unfortunately, however, Irma got pregnant out of wedlock, bringing great shame on the family. Her parents forced her to give the baby up for adoption, after which Irma was reportedly never the same. She had a nervous breakdown and was diagnosed as being schizophrenic. She was institutionalized for the rest of her life, moving from facility to facility over the years.

In the early 1990s, Irma’s sister, Mary, decided to move Irma to a nursing home closer to her so that she could visit more often. Irma, who spent twenty years in the previous facility, had a difficult time adjusting to a new environment. She was disoriented and nervous most of the time unless allowed to sit in a chair just outside her room. Mary began to visit daily, insisting that her presence comforted Irma, though it was unclear if Irma really understood exactly who Mary was.

(Originally written: September 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Three Ladies of German Descent in Chicago appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 24, 2022

“Nothing Would Stay”

Marta Sirko was born on October 12, 1935 to Yaroslav and Kateryna Sirko, who were Ukrainian immigrants to Brazil. They fled Europe in the early 1930’s to avoid the war they felt sure would soon erupt. In Brazil, they were able to buy a small farm and eek out a meager existence, eventually having nine children.

Like most of her siblings, Marta attended elementary school, but according to her older sister, Zoya, “nothing would stay” for poor Marta. Though she was obviously never officially diagnosed with a learning disorder, Marta found school very difficult and often failed. Zoya attempted to help Marta, but Marta would repeatedly tell her that the teacher’s words “go right through me.” She eventually gave up and stayed on the farm to help her mother with the eight other children.

As a young woman, Marta decided that she wanted to go live on her own in town, which happened to be seventy-five miles from the farm. Her parents agreed, and she tried it for about three months before she got too homesick and dejectedly returned to the family. Back on the farm, Marta continued to help her mother and watched as all of her siblings eventually left to either get married or immigrate to the United States.

When Marta was about twenty-seven years old, she again voiced her desire to leave. One of her brother’s, Josef, had immigrated to Philadelphia, and Marta proposed to go and live with him there. Her parents agreed and sent Zoya, too, hoping it would be a better life for the sisters. Both Marta and Zoya were able to get a job in a factory, where they remained for over fifteen years. Zoya eventually married and moved out of her brother’s house, but Marta stayed, as she had nowhere else to go. She was not a very social person, Zoya says, and had a difficult time learning the language. When she wasn’t working, she spent much of her time watching Josef and his wife’s four children.

One night, however, when Marta was in her early forties, a friend persuaded her to go to a party. Marta was reluctant to go, but finally agreed and was introduced to several people, one of them being a man by the name of Nicolau Honchar, who was also Ukrainian. According to several people at the party, Nicolau was merely cordial to Marta that night, but somehow she developed an extreme crush on him and believed the two of them to be in love. Though she never saw Nicolau again, Marta dreamed of marrying him and spoke of little else for weeks. When Marta’s friend finally told her that Nicolau was not interested in her and was in fact dating someone else, Marta suffered a sort of breakdown.

According to Zoya, Marta was always a very nervous, anxious person who worried constantly and could not navigate the normal ups and downs of life. The episode with Nicolau, she says, seemed to push Marta over the edge. She spiraled into a depression, frequently calling herself stupid and an idiot. “What is wrong with me?” she would ask over and over, referring to the fact that she wasn’t married and that she hadn’t been able to succeed at school, learn to drive, or to speak English.

Shortly after her breakdown, Marta went through “the change of life,” which, Zoya says, made everything worse. Marta’s only pleasure in life was apparently getting her hair done. As a young woman, she also loved to do embroidery work, but she lost interest in it as her depression grew worse. In 1981, Zoya, at her wits’ end, finally decided to take her sister to a hospital, where she was admitted for depression.

It was at this point that another of the brothers, Ivan, suggested that Marta should come and live with him and his wife, Anna, in Chicago for a “change of scenery.” Zoya and Josef, themselves weary from having to care for Marta for years, eagerly agreed with this plan. At first, Marta seemed to enjoy her new surroundings, but she unfortunately spiraled back into a depression. Her anxiety worsened, also, and she began to endlessly pace, refusing to ever sit down. She also began to pick at her skin, which led to several infections. Eventually, Ivan and Anna were forced to hospitalize Marta another four times, the last one being after she attempted to slit her wrists. It was after this particular incident that Ivan and Anna “admitted defeat,” and decided to admit Marta to a nursing home.

Marta, for her part, is not making the best transition to her new home. She constantly walks the hallways and says little, even with the help of an interpreter. Frequently, she “zones out” when people speak to her, looking straight ahead as if she doesn’t hear or see the person trying to address her. She is not interested in meeting other residents, nor in joining in the home’s activities. The only thing she seems to enjoy is getting her hair done.

(Originally written: August 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Nothing Would Stay” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 17, 2022

“So Damned Mediocre!”

Leona Wilson was born in Oklahoma on December 16, 1906 to Nigel Wilson and Elizabeth D’Evers. Nigel was born in England and had a passion for the American Wild West since the time he was a little boy. So strong was his desire to be a cowboy that he ran away from home as a teenager and got a job on a ranch in Colorado. His father eventually tracked him down and made him return to England to finish his education, promising that once he did so, he would be free to do as he liked.

Leona Wilson was born in Oklahoma on December 16, 1906 to Nigel Wilson and Elizabeth D’Evers. Nigel was born in England and had a passion for the American Wild West since the time he was a little boy. So strong was his desire to be a cowboy that he ran away from home as a teenager and got a job on a ranch in Colorado. His father eventually tracked him down and made him return to England to finish his education, promising that once he did so, he would be free to do as he liked.

Nigel accordingly graduated from university with a degree in business and immediately returned to America. He first went to Chicago, where he met a young woman, Elizabeth D’Evers, at the Presbyterian Church he was attending. The two of them began dating while Nigel worked in an accounting firm to earn money to go back out west. Eventually, Nigel and Elizabeth married and had two children, Edmund and Gerald, before they had finally saved enough money to buy a ranch in Oklahoma.

Once settled in Oklahoma, the Wilsons had three more children: Margaret, Leona and Catherine. Leona says that Margaret was her “mother’s pet” and could do no wrong. She was very spoiled, and, consequently, Leona hated her. The Wilson’s remained on the ranch for about ten years before Nigel decided he had had enough. Somehow, ranch life was harder than he had remembered it being as a boy. The family moved again, this time to Denver, where another baby, Herbert, was born. Leona says that she hated Herbert more than she hated Margaret, as he was “a terrible brat and annoyed everyone.”

Leona reports that she had a tolerably good childhood. Her family, she says, wasn’t terrible; their great sin was that they were “so damned mediocre.” She carries a bit of a chip on her shoulder, however, as she feels like she was pretty much ignored and even cheated by her parents. Margaret and Herbert, she says, got everything they wanted, while “I was given nothing,” she says.

Leona remembers begging her parents for violin lessons, for example, but they refused to waste money on such a thing. Later, she begged for art lessons, but they again “ignored me and never encouraged me at all!”

After Leona finished elementary school, Nigel and Elizabeth decided to divorce. Leona is not sure why, but she thinks it might have been because Elizabeth wanted to move back to “civilization.” Thus Elizabeth took the three girls and Herbert and returned to Chicago, while Nigel and the two oldest boys remained in Colorado.

Elizabeth and the children moved in with her parents, the D’Evers, and Leona started high school. She eventually graduated and then begged to be allowed to attend the Art Institute, but Elizabeth and her well-to-do parents refused to throw money away at such “utter nonsense.” Leona wrote to her father, asking him to pay for her education, but he also refused.

Deeply resentful, Leona got a job and put herself through school. When she finally graduated with an art degree from the Art Institute, she only had enough money to rent a little studio, where she worked and also began giving art classes. She didn’t have enough money to move out of her grandparents’ house, though, and thus had no choice but to remain there, even though she had grown to seriously dislike them over the years for their “snobbish superficiality. They thought they were something because they had a ‘D’ in front of their name,” she says. “To me, it stood for ‘dumb.’ They thought they were so aristocratic, and it was ridiculous that they only respected people who had more money than them.”

Leona tried her best to ignore her family and their disparaging comments and threw herself into teaching. “It is the greatest fun to teach children,” she says, “because you don’t teach them, they teach you!” After a year of teaching, however, Leona decided to go to New York for a weekend to get away from her mother and grandparents and to also see art museums and galleries. In just a couple of days, she fell in love with New York and returned to Chicago with the intention of packing up and moving there.

She was in the process of going around to different galleries and studios where her friends were to say goodbye, when she happened to meet a new artist, a man by the name of Sherman Abrams. Leona was immediately drawn to Sherman and his work and began following him all around town. She says that she fell in love with him instantly and describes it as “Pow!” Sherman, apparently aware of Leona’s feelings for him, initially tried to avoid her, as he mistakenly thought she was only fifteen. Leona kept finding him, however, and repeatedly invited him to her studio to see her work. Each time he would agree to come but then not show up. Still Leona persevered.

Frustrated by Leona following him, Sherman eventually asked a mutal friend how old she was. The friend said that he thought Leona was in her twenties. Surprised, Sherman finally went to her studio, burst through the door and said “Just how old are you?” When she told him she was twenty-two, he immediately asked her out on a date.

Sherman and Leona eventually married and had two children: Pamela and Rose. Sherman became a very successful commercial artist, and he and Leona were very happy for a time. Sherman’s brothers all loved Leona, apparently, but his mother did not. She resented the fact that Leona wasn’t Jewish, and tried to “make our life miserable,” Leona says. Eventually, the pressure became too much, and the two of them decided to divorce. Leona says that she “grew beyond him.” He was very “juvenile and childish, and his mother wanted him to stay that way.”

After the divorce, Leona packed up Pamela and Rose and moved to New Orleans, where she happily joined the artist community there. She enrolled the girls in a “very good public school in the French Quarter” that emphasized art. Meanwhile, Leona painted, exhibited and taught in various schools. She feels that she was very successful as an artist and as a parent. She is extremely proud of the fact that she devoted so much time to taking her children to see art exhibits, plays, museums and galleries while other women “were at home exchanging housework stories.” She devoted her life to her art and her children and encouraged them to explore any artistic avenue they desired.

As it turned out, upon her graduation from high school, Pamela decided she also wanted to attend the Art Institute. Leona was thrilled with this decision and saw “a lot of promise” in Pamela’s work. Accordingly, she moved them all back to Chicago and contacted Sherman about helping to pay for Pamela’s tuition. She was dismayed when he refused to “give me one cent!” Leona could not believe that Sherman, himself a successful commercial artist, would not encourage his daughter to study art and concluded that perhaps he was jealous of Pamela’s skill. Even now, Leona still seems fixated on this episode in her life, even after so many years have passed. She repeats this story over and over until redirected.

Leona was determined that Pamela should go to the Art Institute, however, and took on two jobs to make the money to pay for it. “I worked night and day,” she says proudly. Similarly, when Rose graduated from high school, she expressed a desire to attend Hunter College in New York to pursue writing. Again, Leona worked two jobs to put Rose through. When both girls were finally finished college, Leona returned to New Orleans to pursue painting and also took up sewing.

Leona remained in New Orleans, living independently, until just about four years ago when she began having difficulty with her health. Pamela suggested that she move back to Chicago. Leona agreed and moved in with Pamela, at Pamela’s invitation, and continued to paint a bit. Not long after the move, however, Leona’s health began to seriously worsen. She had a stroke and also went legally blind. Added to that, she has recently been diagnosed with the beginnings of dementia. She was hospitalized for several weeks after her stroke, and upon her release, the hospital discharge staff recommended nursing home placement.

Leona is very upset about her new living arrangement and has a lot of anger toward Pamela, whom she says “dumped her here.” In turn, Pamela is very sharp toward her mother when she visits, which consist of five- to fifteen-minute intervals. In her more rational moments, Leona says that she understands that it would be impossible to still live with Pamela, but she seems to quickly forget this and grows angry all over again, saying that she paid for half of Pamela’s house and that she should be allowed to live there. At other times Leona is calm and pleasant and attempts to socialize with the other residents. It is hard to participate in activities, though, because of her blindness. She says that she can see light and dark, but no color. “Can you imagine that?” she asks. “What living in a colorless world is like to an artist?” Over all, she seems to be trying to make the best of her situation, but, she says, “I feel empty inside.”

(Originally written: July 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “So Damned Mediocre!” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 10, 2022

Two Spinsters and a Bachelor

Faye Pesek was born on June 28, 1909 to Archibald Pesek and Rita Vesely, both of whom were born in Chicago and were of Czech descent. Archibald was a type of woodworker, Faye reports, and her mother cared for their three children: Lorene, Faye and Albert. Albert died of pneumonia, however, when he was just two years old. Shortly after Albert’s death, Rita became “mentally ill,” and was institutionalized. Thus, the raising of Lorene and Faye fell to Archibald. “Dad always told us that mother was sick and had to live away from us,” says Faye. She says that she missed her mother, but she feels that she had a good childhood none-the-less.

Faye Pesek was born on June 28, 1909 to Archibald Pesek and Rita Vesely, both of whom were born in Chicago and were of Czech descent. Archibald was a type of woodworker, Faye reports, and her mother cared for their three children: Lorene, Faye and Albert. Albert died of pneumonia, however, when he was just two years old. Shortly after Albert’s death, Rita became “mentally ill,” and was institutionalized. Thus, the raising of Lorene and Faye fell to Archibald. “Dad always told us that mother was sick and had to live away from us,” says Faye. She says that she missed her mother, but she feels that she had a good childhood none-the-less.

Faye enjoyed school and had many friends, though she was very close to her sister, Lorene, as well. After graduating from high school, Faye got a job in the accounting department of W.H. Minor and Co., which, she says, was a small company when she started but which grew into a big one by the time she retired at age 68. She never married, she says, because “it just didn’t work out.” But, she adds, “I had a good life.”

She was an active member of her church, Trinity Lutheran Slovak, and volunteered with several Bohemian clubs and organizations, including the Bohemian nursing home. She also enjoyed golfing, bingo, gardening, and dancing. She loved traveling but didn’t like to go alone, so she always went on group tours. She traveled all over the United States and Europe this way.

Recently she was diagnosed with pneumonia and spent many weeks in the hospital. Left very weak, she agreed with the hospital discharge staff that she could not go home alone and helped make the decision herself to go to a nursing home. She chose the Bohemian Home because of all the time she spent volunteering there over the years. “It’s already like my second home,” she says.

Thus far, Faye is making a smooth transition. She is eager to meet people, often waving and saying hello to residents, whether she knows them or not, as the staff push her from place to place in her wheelchair. She is anxious, she says, to make this her new home. “It’s always better to look forward than back,” she says.

Marvin Feldman was born on December 25, 1913 to Ernest and Gloria Feldman, both immigrants from Poland. They met and married in Poland and shortly thereafter immigrated to the United States. Ernest found various jobs upon their arrival in Chicago and eventually worked his way into the real estate business. Gloria cared for their seven children: Clara, Emmie, Warren, Marvin, June, Bernice and Ethel, of whom, only Marvin is still alive.

Marvin Feldman was born on December 25, 1913 to Ernest and Gloria Feldman, both immigrants from Poland. They met and married in Poland and shortly thereafter immigrated to the United States. Ernest found various jobs upon their arrival in Chicago and eventually worked his way into the real estate business. Gloria cared for their seven children: Clara, Emmie, Warren, Marvin, June, Bernice and Ethel, of whom, only Marvin is still alive.

Marvin attended two years of high school and then quit to get a job in an asbestos factory. After a couple of years, however, the dust hurt his lungs so badly that he had to quit. From there he went to work at Skil Power Tools, where he remained until he retired at age 65. Marvin never married. His two loves were playing tennis and traveling. Over the years he won many tennis tournaments, acquiring a whole shelf of trophies and medals. Likewise, he traveled to every state in America, Florida being his favorite. He also enjoyed walking in Chicago’s many parks, classical music, and golf. He lived in the same apartment on Ashland Avenue for over 22 years.

Marvin was doing well, living alone until he recently fainted and was discovered by a neighbor. He was taken to the hospital by ambulance, where he was diagnosed with a variety of heart problems. The hospital staff transferred him to a nursing home, where he has not made a smooth transition. He refuses to get out of bed and has extreme mood swings. Three of his nephews have been located and sporadically appear to visit, but they have not been successful in helping to convince him that he can no longer live alone. He has no interest in meeting other residents and wants only to go home. Staff are trying to find some activity that he might enjoy.

Maria Accardo was born on August 6, 1924 in Chicago to Italian immigrant parents. Maria remembers that her father was named Angelo, but she does not remember her mother’s name. Maria was an only child, apparently, and went “all the way” through school, eventually graduating from high school. She then got a job for a short time as a secretary in the office of a factory, but she found it to be too stressful, so she asked to be transferred to a position on the assembly line and was granted it. It was a job she much preferred.

Maria Accardo was born on August 6, 1924 in Chicago to Italian immigrant parents. Maria remembers that her father was named Angelo, but she does not remember her mother’s name. Maria was an only child, apparently, and went “all the way” through school, eventually graduating from high school. She then got a job for a short time as a secretary in the office of a factory, but she found it to be too stressful, so she asked to be transferred to a position on the assembly line and was granted it. It was a job she much preferred.

Maria was a quiet, simple girl who loved music and dancing at the Aragon, as well as listening to baseball games on the radio with her father and going to movies. When she was in her thirties, her parents decided to move to Indiana, so Maria went with them. She had no desire to stay in Chicago and live on her own. She never married and was considered by some to be “slow.” She enjoyed singing in the church choir and only traveled once—taking a trip to New York with a friend.

When Maria’s parents passed away, an “aunt” (or perhaps she was merely a friend of the family) took Maria back to Chicago to live with her. At the time, Maria was over forty years old. Recently, however, Maria’s aunt passed away, and Maria found herself unable to cope alone. One of her aunt’s great nieces stepped in, then, and helped Maria to admit herself to a nursing home. She is making a smooth transition, though she is very quiet and shy. She seems content with her new home and prefers to sit in the day room, watching people, though she will join in activities if invited.

(Originally written: June 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Two Spinsters and a Bachelor appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.