Michelle Cox's Blog, page 13

March 3, 2022

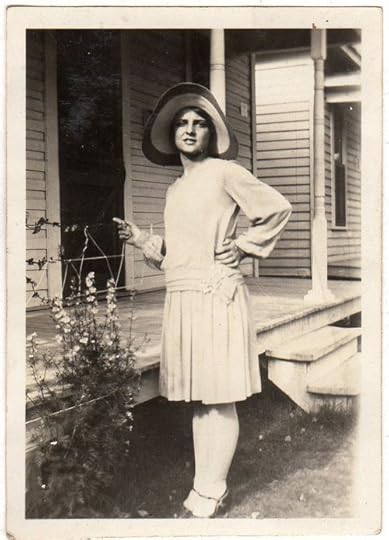

A Girl Like Addie

Liberty Adelaide Appleby was born in Chicago to Alice Myers and Maurice Von Pfersfeld on July 4, 1914. Because she was born on Independence Day, Maurice insisted they name their new daughter Liberty, though Alice had wanted to call her Adelaide. They settled for Liberty Adelaide, but she was always called Addie.

Addie does not remember much about her mother’s family, except that they were of German descent. Her father’s family, she says, immigrated from Alsace-Lorraine. Maurice apparently loved tell the story of how the Von Pfersfeld’s were once barons back in the “old country” and how his grandfather, one Archibald Von Pfersfeld, eloped with a penniless woman and immigrated to America. They made their way to Chicago and to Logan’s square in particular, where they had three sons, one of them being Johann, who was Maurice’s father.

Maurice grew up in Logan’s square and got a job as a delivery truck driver for the Olsen Rug Company. He met Alice Myers at a church picnic, and after a short courtship, they married. They eventually got their own apartment on Campbell, where they raised their two children: Addie and Marie, who were six years apart.

Addie graduated from elementary school and had begun to attend high school when the stock market crashed, throwing the country into the Great Depression. Maurice, like thousands of others, lost his job. Without Maurice’s paycheck, the family was thrown into poverty, as they had little savings. They didn’t feel poor, however, Addie says, because everyone else was “in the same boat.”

At some point, the government began giving out food at the local Armory, which the Von Pfersfeld’s had no choice but to accept. Alice, being a proud woman, could not quite bring herself to go down and stand in line, so she sent Addie to go for her. “It was good food,” Addie says, “but it got boring, so we traded with people in the neighborhood.” Addie says that the Depression was a terrible time during which a lot of people suffered, but, on the other hand, she says, it was a time of great camaraderie among neighbors, the likes of which she never witnessed again, even during the war. “People looked out for each other back then.”

Addie quit school and began looking for a job, which turned out to be easier to get than it was for her father. Addie attributes this to her good-looks. “I had a man-stopping body back then,” she says, “and a personality to go it!” Jobs were therefore never hard for her to come by. It was keeping the job that was the problem, as she was forever getting fired for slapping an owner or a manager for “feeling me up” or trying to trap her in a back room. “I wasn’t that kind of girl!” she says. Addie claims to have had so many jobs, often working two or three at a time over the course of her 53-year working career, that she can’t remember them all.

One of her favorites, though, was working at the Chicago World’s Fair, first at an ice cream booth and then as a “Dutch Girl” for a Dutch Rubber Company. Addie says that this was her favorite job because all she had to do is dress up in a Dutch Girl costume and pass out flyers all day. “It was a great job,” Addie says, “because it was easy, and I got to see the whole fair on my lunch break.”

Over the years, Addie had dozens and dozens of waitress jobs. She also worked as a dishwasher, a maid, a floor-scrubber, a counter girl/hair curler demonstrator at Marshall Field, and even as a solderer at a radio factory, which, she says, was terribly boring but paid well. When these more mundane jobs petered out, Addie was obliged to venture into more risqué territory, for which she was easily hired because of her extreme beauty.

Some of these more risqué jobs included working as a “bookie’s girl,” which meant she collected coats and was supposed to serve as many drinks as possible to the “clients.” She also worked as a “26 Girl,” which was a dice game popular in Chicago bars. It was her job to collect money, keep score and encourage men to order drinks, for which she received a percentage of the house’s profits. After that, she took a job as a “taxi dancer” at a local dance hall, where, she says, “I was paid to stand around and look pretty.”

Taxi dancers apparently originated as dance instructors. They were hired by dance halls to instruct men in how to dance. For ten cents, a man could dance with a pretty girl for one dance, thus earning the girls the nickname of “dime-a-dance girls.” Addie says that there really were some shy, quiet boys who actually came in with the intention of learning to dance, but most of the men that came in were there to “feel the girls up.” It was infuriating, Addie says, because the dance hall owners claimed that there was a “no touching” policy, but they not only looked the other way, but actually encouraged men to “have their way.”

This, plus the fact that she would not get off until two or even sometimes four a.m., caused her to finally quit this job, despite the fact that she had a little gang of neighborhood boys who looked after her. These boys knew Addie to be “a good girl,” and out of worry for her would wait at the el stop each night and follow her, at a discreet distance, until she made it safely home.

From taxi dancing Addie went to being an usherette at a burlesque theater, which made taxi dancing seem like “a kid’s birthday party,” she says. Desperate for money, she saw an ad in the paper when she was nineteen for usherettes at a burlesque house downtown on Monroe. She went to apply and was shocked to find that hundreds of women were lined up around the block, hoping for one of the fourteen available positions.

Addie almost gave up hope then and there, but decided to join the line and take her chances. Once inside, a line of girls were called up on stage and had to show their legs and then lift their skirts to show their buttocks. The men in the seats who were directing these dubious “auditions,” then went down the line, pointed at each girl and either said “left” or “right,” indicating which door they should go through, off stage. The door to the left led to the alley, and the door to the right led to a little side room. Eventually, all the girls in the side room had to line up on stage once more, and this time, the men went down the line, saying “you, you, you, etc.” until they had chosen fourteen girls.

Addie was one of the chosen. She was given a beautiful costume and briefly trained in the art of ushering. The girls were closely chaperoned and a very strict policy of no touching or “hanky-panky” between the customers and the girls was enforced. In fact, there were two male “ushers” who were really there to act as bouncers if any man in the crowd got out of line with the girls. The girls were also required to go to the restroom in pairs for safety’s sake, though, Addie recalls, this policy once backfired for her.

Addie tells the story of how one night, not long after she started, she and a partner went to the restroom as per the policy, but not long after entering the bathroom, another of the usherettes, a girl by the name of Mimi, grabbed her from behind and started kissing her neck. Addie loudly protested and pulled away. Mimi quickly apologized, saying that she had obviously made a mistake. Most of the usherettes, and even the dancers, she told Addie, were actually lesbians. Despite this incident, Mimi eventually became Addie’s best friend and invited her after the shows to her “lesbian parties,” as Addie called them, though none of the girls ever made an advance on Addie again. Mimi became her protector and would often attempt to shield the “innocent” Addie’s eyes from some of the girls “making out” in dark corners.

At some point in time, Addie, who claims to have had “hundreds” of marriage proposals in her lifetime, accepted the hand of one Bill Zielinski and had a child, Hattie, with him. It was a very brief marriage, however, and they divorced when Hattie was only one year old. Addie does not like to talk about Bill or about this time in her life and offers very few details. If asked about it, she will swiftly change the subject.

Apparently, when Hattie was still very little, Addie again married, this time to a man named Arthur Appleby. Arthur was an insurance salesman, and after marrying him, Addie, for the first time in her “adult” life, did not have a job, but instead stayed home to be a housewife and to care for Hattie. Not very long into their marriage, however, Arthur developed Parkinson’s disease and became an invalid, forcing Addie to go back to work. At times she was able to get Hattie, who had inherited her good looks, modeling jobs at Marshall Fields, which helped pay some of the bills.

Addie herself was loathe to go back to any risqué jobs, now that she was a wife and a mother, and tried to find something more respectable. A friend of hers had a job as a private secretary and Besley Wells Tool and Dye and told Addie that there was an opening there as a bookkeeper. Addie knew nothing about bookkeeping, so she went to the local high school, borrowed a book on bookkeeping, and read it overnight. The next day, she went in to Besley Wells, applied for the job, and got it. After several years, Besley Wells was bought by Allied Signal, but Addie was able to keep her position in the Loop office. Eventually, however, she was transferred to the office in Beloit, Wisconsin, where she was taught to use a computer. She stayed there for a year before moving back to Chicago.

In all, Addie worked as a bookkeeper for thirteen years before eventually retiring. Arthur died during a surgery the year before she retired. She was sad, of course, she says, but if she were to be honest, it was a relief to not have to care for him anymore.

Despite having to basically raise Hattie herself, work, and take care of an invalid husband, Addie says she was always up for anything. She needed to be busy all the time and always had “a spark” in her eye. Nothing, she says, was too hard for her if she put her mind to it. She had many, many interests and hobbies: ceramics, crocheting, horses, drawing, decorating, home repair, reading, hunting, and fishing, to name a few. She also routinely went to the Art Institute, the Field Museum and the Lincoln Park Zoo and Gardens. If a new interest caught her attention, she would go to the library, find a book on the subject, and learn all about it or teach herself to do whatever it was.

Hattie eventually married and moved to the suburbs, and in the latter years, Addie moved in with her sister, Marie. The two sisters apparently got along very well until Addie had to have bypass surgery in 1990. From there things went downhill, and Addie was eventually diagnosed with COPD and chronic heart failure. The discharge staff advised a nursing home for Addie, especially as she has been given a terminal prognosis and has also entered a hospice program.

Addie is aware of her impending death, but says she is determined to enjoy herself until the very end. She is trying to make the most of the activities at the home but mostly enjoys talking and telling her life story. She is extremely lively and interested in all things around her. Her daughter, Hattie, visits regularly, as does her sister, Marie, both of whom seem to be having a harder time accepting Addie’s situation than she herself is. “What can I say” Hattie asks, “that my mother hasn’t already said? She is an original. A one-of-a-kind, and I’ll miss her so much when she’s gone.”

(Originally written: December 1995)

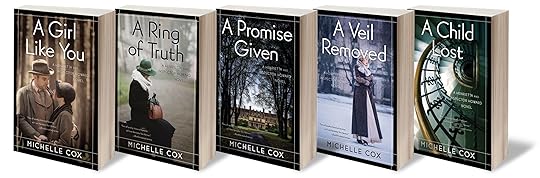

(Author’s note: The protagonist of my Henrietta and Inspector Howard series, Henrietta Von Harmon, is based on Liberty Adelaide Appleby! Many of the details of her life as described above can be found in book one of the series, A Girl Like You.)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post A Girl Like Addie appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 24, 2022

“Give Me Just One More Chance to Take Care of Her”

Moira Hardy was born on December 16, 1907 in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia to Kenneth Stewart and Effie MacCain, both of Scottish descent. Kenneth was a foreman in a steel mill there, and Effie cared for their eight children: Alan, David, Sonia, Edna, Angus, Beatrice, Moria, and Ewan. Kenneth passed away of a heart condition at age 78, and Effie died at age 92 of “old age.”

Moira Hardy was born on December 16, 1907 in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia to Kenneth Stewart and Effie MacCain, both of Scottish descent. Kenneth was a foreman in a steel mill there, and Effie cared for their eight children: Alan, David, Sonia, Edna, Angus, Beatrice, Moria, and Ewan. Kenneth passed away of a heart condition at age 78, and Effie died at age 92 of “old age.”

Most of Moria’s siblings quit school early and got married, but being one of the younger ones, Moria was encouraged to finish high school. She did graduate in 1925 and then went on to nursing school at St. Vincent’s in New York. She earned her RN, of which she and her entire family were extremely proud. She got a job working for the American Red Cross and traveled all over the United States, which she very much enjoyed.

While still in her twenties, she happened to work with a young doctor by the name of Joseph Hardy at Benedictine Hospital in Kingston, NY. The two fell in love and married in 1935. They bought a home and settled down in Kingston and had two children: Margaret and Edmund. According to Edmund, his parents always seemed relatively happy, but in 1951 they announced that they were getting a divorce. Edmund says that he was never told any of the specifics beyond that they had simply “grown apart.” Edmund suspects that his father may have had an affair, but that it was certainly never talked about. After the divorce, Joseph decided to travel around the United States and died suddenly of a heart attack in 1963.

Meanwhile, Moria found she had to return to work, having given up nursing to stay at home with Margaret and Edmund, who were in their teens at the time of the divorce. She moved to the Bronx with them and was able to find a job at Charles A. Pfizer, which was a pharmaceutical company in New York. She worked there until she retired at age 62, and then took a job at Baptist Nursing Home in the Bronx until 1973, when she quit at age sixty-six.

Fully retired at that point, Moria split her time between gardening, card clubs, and traveling, often going to Vermont to see her daughter, Margaret, or back to Nova Scotia to see her siblings, or coming to Chicago to visit her son, Edmund, and his family. As the years went on, however, all of Moria’s siblings passed away, as did her close friends in New York. She became very lonely and withdrawn, and Edmund eventually convinced her in 1992 to move in with him and his wife, Shirley, in Park Ridge.

Things were going well, apparently, until about six months ago when Shirley noticed that Moria had a bad sore on her leg, which she seemed to be trying to hide behind bandages. Edmund wanted to take her to the doctor, but Moria insisted that as a former nurse, she knew how to take care of a sore and was very offended by what she called his “meddling.”

Eventually, however, Moria did go to see a doctor, who diagnosed it as gangrene. It did not respond to treatment, unfortunately, and Moria had to have her leg amputated. She remained in the hospital for six weeks, during which time a feeding tube also had to be inserted because she had stopped eating. When it came time for Moria to be discharged, the hospital staff strongly urged Edmund and Shirley to put her in a home where she would have full-time care. Edmund was, and still is, racked with guilt about his mother’s amputation and frequently says that if only he had insisted she see a doctor earlier, her leg may have been saved. He was therefore very reluctant to place his mother in a home, telling the hospital staff that he wants “one more chance to take care of her.” Eventually, however, the social worker convinced him that a nursing home would be much better for Moira.

Moira is adjusting relatively well to her new home, but she is very disoriented. She rarely speaks and when she does, she simply asks to go home. She smiles often, however, and seems to like having a roommate. Edmund, on the other hand, is having a very difficult time and needs constant reassurance from the staff that he has made the right decision. He is perhaps unrealistic in his hope that she might recover enough to come back and live with him and is already asking if she might be able to come home for a short break for Christmas.

(Originally written: November 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Give Me Just One More Chance to Take Care of Her” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 17, 2022

Married in His Mind

Arthur Kowalski was born on February 14, 1911 in Chicago to Jacek and Elsie Kowalski, both immigrants from Poland. Neither Jacek or Elsie had had much education in Poland, but upon arriving in Chicago, Jacek quickly found a job working on the railroads. As the years went on, he began to get involved in real estate and would buy businesses, such as corner grocery stores, hardware stores and taverns, operate them for a little while and then sell them for a profit. Elsie, who could neither read nor write, even in Polish, cared for their four children: Sophie, Teresa, Arthur and Nora. When the children got a little older, she also helped Jacek keep the books for his businesses, as, it turns out, she was good with figures despite not being able to read.

According to Arthur, his father had a good reputation in the business world, but he was “rough and tough” and drank heavily. Elsie was always having to be the peacemaker of the family; she wasn’t afraid of Jacek and wouldn’t back down or cower to him. Arthur says that he never got along with his father, and says that he would have run away had it not been for his mother.

Eventually, Arthur graduated from high school, and his father surprised him by offering to pay for him to go to college so that he could become a lawyer and help him with his businesses. Arthur refused for two reasons. First, he had no desire to go into law, as he saw this as “a profession for liars.” Secondly, he felt too guilty to take his father’s money when the whole country was going through the Great Depression. His father tried hard to “bully” him into going, but Arthur still refused.

Instead, Arthur got a job, or, rather, a string of jobs, though they were hard to come by. He began going around with a peddler, then found a job as a caddy and then as a printer. None of these he liked very much, so one day, his mother slipped him some money to go downtown to a proper employment agency. They accordingly sent him to an office supply company on Madison Avenue for what was supposed to be only a temporary position in the shipping department.

Anxious to prove himself, Arthur worked hard and fast and was soon more productive than anyone in the department, so the company kept him on. He offered to work nights and weekends in addition to his day shift to save the company from having to hire extra people. His boss liked him so much that when his son came home from college in California, he invited Arthur to socialize with him, wanting the two of them to become friends. Arthur declined, however, saying that they were from two different classes and that he didn’t have the money to hang around “a bunch of college boys.”

Right at about this time, when Arthur was twenty-three, he was introduced at a dance to a young woman by the name of Margaret Paszek, who was just twenty years old. Arthur describes her as “a knock-out.” She was only twenty, but the two began dating. Arthur says he fell in love with her right away, but he insisted on dating for five years because he wanted to be sure that she was the one. “I wanted a solid foundation and some money in the bank before I proposed,” Arthur recalls. Margaret was fine with waiting, Arthur claims, as her mother was very strict and probably wouldn’t have allowed her to get married much sooner, anyway.

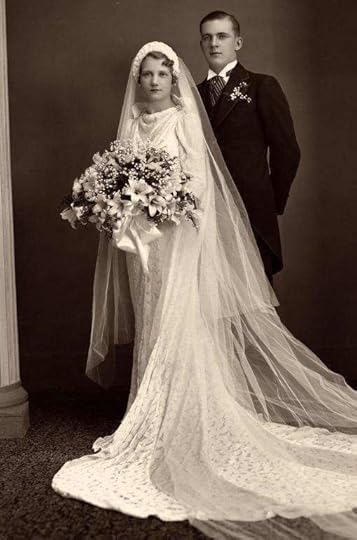

Finally, though, in 1939, Arthur and Margaret married, but Arthur refused to have a reception, as he did not want to dig into his savings with no guarantee of getting it back in gifts from Margaret’s “mooching relatives.” Despite this unusual beginning, the marriage seemed to go well at first. Arthur continued working feverishly at the office supply company and rose to be not only a bookkeeper, but a manager. He then decided to start taking night classes to get his CPA. He was not very far along, however, when the war broke out, and he immediately joined the army.

Arthur was very proud of the fact that before he left for the army, he had saved up over three thousand dollars, so he knew Margaret would be okay in his absence. As a child, his hobby had been to build radios, so once in the army, he ended up in radar. He was offered officer training, but because it would mean a longer commitment, he declined it. While he was stationed in the U.S., he came home to Margaret every single weekend, no matter what it took. Then, when he was eventually shipped overseas, he wrote her an eight-to-ten page letter every day.

Arthur was eventually shipped to the jungles of New Guinea, about which he has many amazing stories, but was discharged home in 1944, severely underweight and diagnosed with malaria and “jungle rot.” He arrived home, weak and sick, to Margaret and their six-month old daughter, Frances, or Franny. Everything, though, had changed, he says. Desperately ill, Arthur says that all he wanted to do was stay home and rest and get to know Franny. He had no interest in “sex, drinking or going out,” but Margaret was “raring to go.” She began to resent him wanting to stay home all the time, and began instead to go out with her girlfriends once a week. Gradually, it grew to multiple times a week. She started drinking more and even told him that she was having affairs. None of this seemed to phase Arthur, however, who simply lavished all of his love and attention on Franny.

Finally, when Franny was nine years old, Margaret left Arthur and sued for a divorce, which Arthur, a strict Catholic, refused to give her. Instead, he suggested they buy a house in Oak Park and try to start over, but Margaret refused as she saw this as a ploy on his part to get her away from her family who all lived nearby. Margaret’s lawyer then proposed a legal separation, which Arthur also refused. Arthur sought the counsel of the Church Chancery and finally agreed to the divorce, though he saw this as a grave sin, if he could have complete custody of Franny, a condition he expected Margaret to refuse. Shockingly, however, she accepted, and the two went their separate ways. Arthur got an immediate annulment, but remained “married in my mind” for the rest of his life.

From that point on, Arthur began his days at 5 am and ended them at midnight. He devoted himself to caring for Franny. He did all the housecleaning, the cooking, the laundry and the ironing. He curled Franny’s hair in the morning, took her to school, attended her functions, picked her up from school, and had dinner ready every night by 5:30 pm. He was determined, he says, to give Franny a “normal” life and to make up for the lack of a mother figure. He even made it a condition for any new job he began that he would be allowed to leave every day at 4:55 pm, so that he would be on time to pick up Franny.

When he had returned home from the army, Arthur had been offered a chance to go to college on the G.I. bill, but at the time he turned it down, as he felt the stipend was not enough to support the three of them. He instead asked for job training, and they set him up on a two-year program to work in the offices of General Motors. Again, he was extremely industrious, productive and efficient, and he remained there beyond the original agreement, staying for a total of eight and a half years. His whole career was spent working in the offices at car dealerships in some sort of bookkeeping or accounting capacity. He was always in charge of a large staff of office girls, whom he hired, trained or fired, as needed. He feels he was a strict but fair boss and credits himself as being exceptionally honest, precise, stubborn and persistent. He admits to being a workaholic and a perfectionist. He was frequently offered the “top position,” but he never accepted it, though he knew he could do the work, because he felt he would not be fairly compensated since he did not have a college degree. As it is, Arthur is extremely proud of his work and his accounting skills and wishes he could have done more with them.

He is also proud of Franny and his accomplishment in raising her, though he did have some trouble with her during her teen years. During that time, she began covertly seeking out her mother, Margaret, who, Arthur says, “filled her head with lies about me.” Several times Franny ran away and when she was only seventeen, she got pregnant out of wedlock. Arthur was at first devastated by this, but eventually came around to the new baby, Tommy, whom Franny refused to give up for adoption, despite Arthur’s pleading. In the end, Arthur helped Franny to raise Tommy, who turned out to be “a wild one.” Attempting to tame him, Arthur forced him into the ROTC during high school, and often threatened him with sticking him in the navy. When Tommy finally graduated from high school after years of anguish on Arthur’s part, he really did go and join the navy and was stationed in Florida. Many times he has apparently tried to apologize to Arthur for his past behavior and any hurt he might have caused Franny and Arthur, but Arthur has stubbornly refused to accept his apologies.

Besides working and caring for first Franny and then Tommy, Arthur also cared for his mother, Elsie, who was in a nursing home for the last seventeen years of her life. Not only did Arthur visit her every day, but he would insist on getting her up, changing her clothes and her bedding, and taking them home with him to launder. He says he had no time for hobbies, travel or friendships. His socialization mostly consisted of relationships at work, though, he never dated anyone or even entertained that thought, he says, repeating that he remained “married in his mind.”

Just recently, he was admitted to the hospital for a hernia surgery and is therefore staying in a nursing home for a short period of time while he recovers. He lives alone now, Franny having eventually married, and keeps himself busy, he says, with housework and gardening. Arthur is a very pleasant, sweet man who has an amazing memory and will endlessly share stories of his life if asked.

(Originally written: July 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Married in His Mind appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 10, 2022

They Met at a Candy Shop and Stayed Together for Fifty Years!

Regina Dubala was born on March 24, 1923 in Chicago to Lew Wojciechowski and Stefania Mazur, both Polish immigrants. Regina does not remember what type of work her father did, but she does remember that her grandfather was a lawyer back in Poland. Her mother cared for their four children: Casper, Regina, Albert and Lucy.

Regina Dubala was born on March 24, 1923 in Chicago to Lew Wojciechowski and Stefania Mazur, both Polish immigrants. Regina does not remember what type of work her father did, but she does remember that her grandfather was a lawyer back in Poland. Her mother cared for their four children: Casper, Regina, Albert and Lucy.

Regina went to school until the eighth grade and then got a job in a linen supply company as a stocker. She worked there for five years until she was eighteen years old. At that time, she met a young man by the name of Frank Dubala, three years her senior, at a neighborhood candy shop.

Regina was in the habit of stopping at the candy shop from time to time on her way home from work. Regina reports that she never noticed Frank and his friends, who went there frequently, but Frank, on the other hand, noticed Regina right away. In fact, he says that he fell in love with her at first sight and vowed that she was the girl he was going to marry. He confided this to his friends, who found Frank’s prediction enormously funny, especially considering the fact that Frank and Regina had yet to actually meet. Eventually, however, Frank worked up his courage and asked Regina out and was shocked when she agreed. Regina claims that she had no idea he was interested in her until he asked her out. The two of them hit it off right away, however, and, as Frank predicted, they married within six months.

Not long after they were married, WWII broke out. Frank joined the army and was sent overseas to fight. During the three long years that Frank was gone, Regina lived with her parents and cared for her and Frank’s first baby, Edward, who was born while Frank was away. “It seemed strange,” Regina says, “that one minute we were laughing in a candy shop and the next he’s a soldier and I’m a mother.”

When Frank finally returned home, he and Regina had to get to know each other all over again, and Frank had to get to know his little boy. They eventually got a small apartment on Devon Avenue, and Frank found work as a truck driver. Regina, meanwhile, had another baby, Lois.

Regina and Frank apparently had a very good marriage. They enjoyed going to bars to meet up with Frank’s friends from the service, where they would joke around and talk about their days in the war. They also liked to play cards with friends, garden and dance. They never traveled at all. Regina said she had no desire to leave home, and Frank, she says, always claimed that he had seen enough of the world during the war. They very much enjoyed their three grandchildren and often took care of them. Sadly, in 1990, Frank passed away of liver cirrhosis. He and Regina had been together for fifty years.

Regina remained on her own for the next four years until she happened to fall, breaking three vertebrae. After her hospitalization, she was unable to go back to the apartment she had shared all those years with Frank and somewhat reluctantly went to live with Lois. Regina eventually adjusted to her new home, however, but then suffered a stroke. She was again hospitalized, and this time, the hospital discharge staff recommended a nursing home for Regina. After much agonizing debate between Lois and Ed, it was decided that their mother would be placed in a home.

Regina says she understands that she can no longer live with Lois, though she wishes she could. Her left side is partially paralyzed, but she is able to communicate, though her speech is slurred, and can participate in many of the home’s activities. She is in relatively good spirits and is trying to make the best of her situation. “What else can I do?” she says. Lois and Ed visit often, which seems to really cheer her. Regina is shy around most of the residents, but she seems to be making friends with her roommate. She will attend various programs if assisted.

(Originally written: May 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post They Met at a Candy Shop and Stayed Together for Fifty Years! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 3, 2022

Her Mother—Age 93— Still Took Care of Her!

Shirley Denenberg was born on November 24, 1923 in Chicago to Aleksandr Krasny and Marie Altman. Aleksandr emigrated from Kiev as a young man and found work in Chicago making cigars. Marie was born in Chicago, though her parents were also Ukranian Jews. She and Aleksndr had three children: Shirley and Susan, who were twins, and Stanley. When they were little, Marie stayed home with the kids, but once they were in school, she found work as a clerk at Woolworths.

Shirley Denenberg was born on November 24, 1923 in Chicago to Aleksandr Krasny and Marie Altman. Aleksandr emigrated from Kiev as a young man and found work in Chicago making cigars. Marie was born in Chicago, though her parents were also Ukranian Jews. She and Aleksndr had three children: Shirley and Susan, who were twins, and Stanley. When they were little, Marie stayed home with the kids, but once they were in school, she found work as a clerk at Woolworths.

Shirley attended high school for a couple of years and then quit to marry her high-school sweetheart, John Denenberg. John was a couple of years older than Shirley and already had a job driving a bakery truck. After they were married, they got an apartment one floor down from her parents’ apartment in a building on Ridge Avenue. Pretty soon, three daughters came along: Mildred, Anna, and Helen. Shirley stayed home with them and says she enjoyed being a housewife and a mother. When the girls were all in high school, though, Shirley got a job working in the office at a public relations firm.

Shirley’s daughter, Anna, says that her mom was the kind of person everyone wanted to know and that she had lots of friends. She loved bowling and all types of board games, Monopoly being her favorite. She and John did a little bit of traveling in their retirement and visited California, Texas, and Nevada before John died in 1988 of Parkinson’s and Liver Cancer. They had been married for 43 years.

Shirley experienced several unexpected deaths in her lifetime. Her father died young of a heart attack at age 58, and her twin sister, Susan, died suddenly at age 52. The death of her sister was particularly hard on her, Anna says. When John died, Shirley again grieved and went through a period of exploring the city, perhaps as a way of dealing with her grief. She would ride the CTA all over the city, Anna says, and would spend all day at museums or walking around neighborhoods.

In the early 1990’s, however, Shirley began to slow down and started having a lot of health issues. She had surgery on her legs at one point, and had a number of falls in which she broke her collarbone and ribs. At that point, she was still living in the apartment building on Ridge where she and John had raised their family. Shirley’s mother, Marie, was likewise still living in an apartment one floor above, and was shockingly in better health at age 93 than Shirley. So it was that when Shirley was recovering from her many falls, Marie came down every day and took care of her and cooked meals for her!

Realizing that this was probably not a good long-term situation, Shirley’s three daughters decided that they needed to take action. Anna took Shirley into her home, and Helen was willing to take Marie, but Marie refused to move to Colorado where Helen lives. In recent months, Shirley now requires regular dialysis treatments and has developed other complications, so the decision was made to move her to a nursing home. Anna says it was a very hard decision, but she is trying to do what’s best for her mother.

Shirley is not happy about her placement and is having a very hard time adjusting. She appears depressed and angry most of the time and lashes out at the staff. She does not like to participate in activities, nor does she seem to interact well with other residents. She has become obsessed with her health and wants to talk or complain about it constantly. When staff attempt to redirect her, she becomes angry and demands to go home. Anna visits as often as she can, but she is also caring for her Downs Syndrome son at home, so she is limited in how much she can help. “In some ways,” she says, “it was easier to have mom at home,” but it just got to be too much. She feels guilty that she can’t do more for her mom. Both Helen and Mildred live out of state, and Marie still believes Shirley to be living with Anna, though she has been told otherwise.

Meanwhile, Shirley continues to be upset and unhappy. Anna says that it is hard to see her mom this way – so angry and negative, as she was a very happy-go-lucky person when she was younger. Anna suspect’s that John’s death was harder on her then they all thought. “She put a brave face on for a very long time.”

(Originally written: June 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Her Mother—Age 93— Still Took Care of Her! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

January 27, 2022

“This is Not My Father.”

Christian Aquino was born on May 27, 1914 in the Philippines to Alon and Ligaya Aquino. It is unknown what type of work Alon did, but Ligaya cared for their five children: Juan, Christian, Augustine, Jemina, and Yolanda.

Christian Aquino was born on May 27, 1914 in the Philippines to Alon and Ligaya Aquino. It is unknown what type of work Alon did, but Ligaya cared for their five children: Juan, Christian, Augustine, Jemina, and Yolanda.

Christian went to high school and then to college and earned a BA in education. After he graduated, he got a job teaching English literature in a high school near Manila. In his early twenties, his best friend introduced him to his sister, Anita Salvador, and the two of them began dating. They dated for a full two years before Christian finally proposed to her. Years later, he would often tell the story of how he fell in love with Anita right away but that he wanted to be sure. As it turned out, Anita was a teacher as well, and she continued working even after their four children were born. Anita’s mother came to live with them and cared for the children while Christian and Anita were working.

Education, then, was obviously very important to both Christian and Anita, and they determined that all four of their children would go to college. This was difficult, however, as time went on because Anita’s mother began to have health problems. Thus Anita had to quit working to care for the children, the house, and now her mother as well. They were still able to put the two oldest children, Emilio and Felix, through college on just Christian’s meager salary, but they realized that it just wasn’t enough to put the two youngest through.

Therefore, after much thought and agonizing, Christian finally decided that he would go to America to try to make enough money to put Gabriel and Isabelle through school as well. So in 1969, he made his way to Chicago, taking Emilio and Felix with him, and found work. During the day, he worked in a textiles factory, and at night he worked in a plastics factory and would send the money back to Anita. Not only was the work difficult, but it was very hard on both Christian and Anita to be separated, as they were a very close couple. They stayed in contact mostly by writing letters back and forth. Occasionally, maybe once a year, Christian would travel back to the Philippines for a visit, but he did not go more than that because of the cost. After eight long years, however, in 1977, both children finished college, and Christian was finally able to retire. He then sent for Anita and Gabriel and Isabelle to come join him and Emilio and Felix in Chicago.

Isabelle says that their father always referred to himself as a teacher, as if the years he spent working in factories didn’t count. “He was very proud of being a teacher,” she says, and was an avid reader. “That was his passion.” He was also proud, she says, that all of his children went to college and ended up with professional jobs. Both Gabriel and Felix became teachers, while Isabelle became a nurse and Emilio an engineer.

Once reunited, Christian and Anita got a small apartment on Carroll Avenue and joined a Methodist church near there. They never traveled except back and forth to the Philippines, where they would stay for several months at a time.

It was during one of these trips that Anita fell and broke her hip. Relatives called Isabelle to tell her what had happened and to relate that Christian didn’t seem able to handle the situation, saying that he seemed confused and that he was “a bit off.”

Isabelle flew to the Philippines and helped bring her parents back to Chicago, where they went to stay with Emilio’s family while Anita recovered, which seemed the first priority. Isabelle insisted, however, on also taking her father to a doctor to be examined, as she herself could see the confusion and disorientation that the relatives in the Philippines had told her about. Sadly, the doctor diagnosed him with Alzheimer’s, which was a crushing blow to the whole family. All of them were devastated that their “pillar of a father,” who was so intelligent and who had worked so hard for them would soon be reduced to nothing.

Both Anita and Christian remained with Emilio until it got to be too much. Not only was Christian beginning to wander, with Anita unsteadily trailing after him, trying to get him to come back, but he was beginning to have violent outbursts as well. So it was that with very heavy hearts, the children all made the decision to place them in a nursing home.

As the only daughter, the arrangements fell to Isabelle, and she chose a place very near to her. Anita and Christian remained devoted to each other, even in the nursing home, so that when Anita eventually died, Christian was inconsolable. According to Isabelle, her father does not fully comprehend that Anita is dead, though he did attend her funeral. Once back at the nursing home, however, he continued to search and ask for her and grew ever more desperate to find her. Eventually, he began to lash out and to have “violent episodes,” which the home dealt with by sending him to the psych unit at the closest hospital. Fed up with this, Isabelle decided to place him in a different home and chose one where she personally knew many people on staff.

At this new home, Christian so far seems calm and exhibits no problem behaviors. Isabelle comes herself to give him a bath and cut his hair, which seemed to be a source of great agitation for him in the other nursing home. His sons visit as well, though it is a long drive from where they live. Christian remains confused and still asks for Anita. He is either withdrawn, wanting to sit alone in the dayrooms, or is anxious and wanders the halls. He will participate in activities for a short time, but then will get up and leave. “It’s tragic,” says Isabelle. “This is not my father. He was such a lovely, lovely man. He could talk to anyone, and he knew so much.”

(Originally written: March 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “This is Not My Father.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

January 21, 2022

The Egg Man and the Noodle Girl

Sophia Chalupa was born on July 17, 1918 in Chicago to Victor Fiala and Renata Doubek, both of whom were immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Victor worked as a railroad laborer and mechanic in a town near Prague, and after he married Renata Doubek, the two of them decided to immigrate to Chicago in 1908. They settled in the Pilsen neighborhood, and Victor found work in a factory. Renata cared for their three daughters, of whom Sophia was the youngest.

Sophia Chalupa was born on July 17, 1918 in Chicago to Victor Fiala and Renata Doubek, both of whom were immigrants from Czechoslovakia. Victor worked as a railroad laborer and mechanic in a town near Prague, and after he married Renata Doubek, the two of them decided to immigrate to Chicago in 1908. They settled in the Pilsen neighborhood, and Victor found work in a factory. Renata cared for their three daughters, of whom Sophia was the youngest.

Sophia went to school until the sixth grade, when she quit to get a job in a noodle factory. It was her job to weigh the noodles, and she worked there until she met a young farmer by the name of Adam Chalupa.

Adam Chalupa was born on March 15, 1914 in Chicago to Zavis Chalupa and Sara Bobal, who were also Czech immigrants. Zavis had a small farm outside of Brno in Czechoslovakia and also ran a bakery in town. When he married Sara, they, too, decided to try their luck in America and set sail in 1904. They made their way to Chicago, where Zavis bought a small farm on the southwestern edge of the city limits. They had two children, Adam and Amelia.

Adam completed high school and then helped his father to run the farm. Each week, it was his job to drive a load of eggs into the city to sell to various factories, one of them being the Hong Kong Noodle Factory. Over time, he came to know a pretty young woman who worked there by the name of Sophia Fiala. At first he was attracted to how pleasant and kind she always was, but he was further delighted to discover that she was of Bohemian descent, just as was he.

Adam eventually worked up the courage to ask Sophia out on a date and was thrilled when she said yes. They dated for about a year before Adam proposed. The two of them were married in Sophia’s parish of St. Procopius in 1941. After the wedding, Sophia went to live with Adam and his parents until they saved enough money to buy their own farm in Wilmington, Il., which was southwest of the city and not too far from Adam’s parents. Adam farmed and also did custom welding work on the side for extra money, while Sophia cared for their three children: Peter, Frank and Bessie. They were both active in their church, but they mostly lived a quiet life.

In 1969, Adam and Sophia decided to sell the farm and move to Berwyn, Il. where Adam continued to do custom welding on a part-time basis. Sophia began volunteering at St. Odilo’s, and Adam got involved in the Bohemian Concertina Association. Playing the accordion had always been a hobby of his, so now that he had the time, he decided to form a band called the Polkateers.

The Polkateers played together for over twenty years, performing at nursing homes, senior centers, community centers and festivals and libraries. Eventually, however, several members died and replacements proved to be hard to find, so the Polkateers eventually disbanded. By then, all three of Adam and Sophia’s children were married with families of their own. Peter had married and moved to Cincinnati, and both Frank and Bessie had moved to Batavia, Il.

Sophia, never having learned to drive, longed to be closer to their grandchildren, so Adam sold the house in Berwyn in 1981 and they moved to Batavia to be closer to Frank and Bessie’s families. Sophia became very involved in their grandchildren’s lives and delighted in babysitting for them. Adam and Bessie took a couple of trips over the years—one to Cincinnati to see Peter and his family and one to New York, but otherwise, they were happy gardening and playing cards.

In the early part of 1993, Sophia began having a lot of health problems and was eventually diagnosed with heart problems, diabetes and dementia. Adam tried his best to care for her at home, but found it hard. Finally, with the help of their daughter, Bessie, Sophia was admitted to Walnut Grove nursing home in Batavia. Only a few months later, Adam was diagnosed with colon cancer, among other things, and had to have various surgeries. Upon discharge from the hospital, he was also admitted to Walnut Grove. Adam reports that the staff at Walnut Grove were nice, but he hated the food and longed for the Bohemian dishes that Sophia had always made. It finally occurred to him to move to the Bohemian Home in the city where he and the Polkateers had performed—and where he had always been served delicious, complimentary lunches—for many years.

Bessie and Frank were not too enthusiastic about this plan, as it would make visiting harder for them because of the drive, but Adam was resolute. Thus, both he and Sophia were both eventually transferred to the Bohemian Home, where Adam is acclimating nicely. Sophia, however, who never really got used to Walnut Grove, is having a more difficult time. She is disoriented and combative and spends the day pacing the hallways, asking to go home. She does not seem to remember their time at Walnut Grove and says she feels like a prisoner. She directs her anger mostly at Adam, whom she feels is somehow responsible for their predicament. Adam, meanwhile, though he is concerned for Sophia, is enjoying his reunion with many of the Czech people he came to know over the years, including Otto, a blind resident at the Home who used to work there as a janitor in his younger days and who had befriended Adam many years before.

(Originally written: October 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Egg Man and the Noodle Girl appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

January 13, 2022

The Happy Life of Enid and Michael Walsh

Enid Walsh was born on July 10, 1911 in Rend City, Illinois to Bryn Sayer and Nesta Vaughn. Bryn and Nesta were from the same mining village in Wales and married there. Before they started a family, however, they decided to immigrate to the United States, having heard of mining work from other villagers who had made the journey. Thus, on the advice of friends and relatives, they settled in Rend City, where Bryn was able to easily get work in the mine, having been a miner in Wales since he was a child. Nesta, meanwhile, stayed home and took care of the five children they eventually had: David, Enid, Evan, Reece, and Steffan.

Enid Walsh was born on July 10, 1911 in Rend City, Illinois to Bryn Sayer and Nesta Vaughn. Bryn and Nesta were from the same mining village in Wales and married there. Before they started a family, however, they decided to immigrate to the United States, having heard of mining work from other villagers who had made the journey. Thus, on the advice of friends and relatives, they settled in Rend City, where Bryn was able to easily get work in the mine, having been a miner in Wales since he was a child. Nesta, meanwhile, stayed home and took care of the five children they eventually had: David, Enid, Evan, Reece, and Steffan.

At some point, Nesta’s sister, Mary, and her daughter, Helen, came to live with the Sayer family after Mary’s husband died in a mining accident in Wales. Not long after they arrived, however, Mary passed away, leaving Helen an orphan. Bryn and Nesta took her in permanently, and she and Enid became like sisters.

Enid went to school until the eighth grade and then got a job in a cookie factory. Her job was to pack the cookies into the bags, “but I ate plenty of ’em!” Enid says. After a few years, she quit the cookie factory and got a job in a shoe factory instead and stayed there for several more years, though she reports that the cookie factory was her favorite job.

When she was twenty-eight, she met a young man, four years her senior, at a church picnic. Her cousin, Helen, had since married and moved to the nearby town of Valier, and she often invited Enid to come stay with them for the weekend. On one particular weekend, Enid accepted as usual, glad to have something new to do, and on the Sunday accompanied Helen and her husband, Harry, to church. After church, a picnic was held, and it was there that Enid met Michael Walsh, who was of Irish and Czech descent. The two hit it off and sporadically dated until Michael showed up one day in Rend City to ask Bryn for Enid’s hand in marriage. Bryn said yes, and then Michael went and proposed to Enid. They were married two months later.

Enid and Michael began married life in Rend City, but then moved to Valier, not too far from Helen and Harry. Michael was also a miner and worked in the same mine as Enid’s father and brothers. When the miners went on strike, however, part of the mine was closed down, and Michael found himself out of a job. Rather than stay to see if he would ever get his job back, Enid and Michael made the decision to move to Chicago to try their luck there.

The Walsh’s took a room at a boarding house on Division, and Michael immediately found work driving a truck. He relished this new job, free of the mines, and eventually worked hard enough to start his own truck driving business and to buy a house on Wolcott Avenue. Meanwhile, Enid found work in a factory until she got pregnant with their first child, Doris, and then quit to stay home. Enid wanted more children, but she did not get pregnant again for another ten years and then had another daughter, Patty. Enid loved being a housewife and a mother and also enjoyed reading, bowling and bingo. She says that she and Michael would often go for rides in their car, which they were very proud to own, or just enjoyed talking together. “We didn’t need to go out much,” she says.

The girls eventually married and moved out, leaving Enid and Michael to potter about on their own. Michael sold the truck business in 1979 and retired. The two of them took a couple of trips, one to St. Louis and one to Miami, over the years. They mostly enjoyed gardening and visiting with their grandchildren. Both Enid and Michael remained in relatively good health until the early 1990’s when Enid began having small strokes. She was hospitalized each time but was always able to return home to Michael with the help of a live-in caretaker whom Doris and Patty had hired. According to Doris, however, both of them continued to get more and more forgetful, which worried the girls and prompted them to continue to urge their parents to move into a nursing home. Both Enid and Michael have consistently refused, however, denying that there was any need. When Enid fell on Christmas Day, 1994, however, and broke her hip, the difficult decision was finally made to take her to a nursing home.

Enid is making a slow recovery with her hip, but seems in relatively good spirits. She is a very sweet, quiet woman who is eager to please and follows every direction of the staff to the letter. She wants to go home, however, and does not accept that this is her new permanent home. She misses Michael very much, and is sometimes confused about why he is not here with her.

Michael, for his part, is very distraught and lonely without Enid at home and has slipped into a depression. Doris and Patty are taking turns going to pick him up and taking him to visit Enid once a week, as it is difficult for them to drive in from the suburbs any more than that. Doris is in her sixties and is also caring for her mother-in-law, who lives with her, and Patti is still working and also caring for four children. Each time they bring Michael to the nursing home for a visit, he doesn’t want to leave Enid, but when his daughters suggest that he move into the home with her, he refuses and begins to cry.

(Originally written: December 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Happy Life of Enid and Michael Walsh appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

January 6, 2022

“I’ve Always Been Uncle Elbert.”

Elbert Gurecki was born on December 29, 1912 in Chicago to August Gurecki and Barbara Korczynski, both Polish immigrants. August came to Chicago in 1905 and got a job at Crane Plumbing where he worked for the next forty years. Barbara also arrived in America around that same time, having come here from Poland to live with her older brothers and sisters who had already immigrated. She worked at various odd jobs until she met August at a neighborhood dance and married him. Together they had six children, though two passed away. Their first child, John, died shortly after birth. A year later they had Olga, followed by Elbert, Clifton, Freda, and Estella. Clifton died when he was seven of diphtheria, which Elbert almost died from, as well. Elbert survived, however, but was always sickly and thin. Often left at home while his siblings went to school, he developed a passion for model airplanes.

Elbert Gurecki was born on December 29, 1912 in Chicago to August Gurecki and Barbara Korczynski, both Polish immigrants. August came to Chicago in 1905 and got a job at Crane Plumbing where he worked for the next forty years. Barbara also arrived in America around that same time, having come here from Poland to live with her older brothers and sisters who had already immigrated. She worked at various odd jobs until she met August at a neighborhood dance and married him. Together they had six children, though two passed away. Their first child, John, died shortly after birth. A year later they had Olga, followed by Elbert, Clifton, Freda, and Estella. Clifton died when he was seven of diphtheria, which Elbert almost died from, as well. Elbert survived, however, but was always sickly and thin. Often left at home while his siblings went to school, he developed a passion for model airplanes.

As he grew older, Elbert became stronger and began attending school, quickly catching up to the grade level at which he was supposed to be. He was intelligent and went on to high school, where he attempted to join the R.O.T.C, but he was rejected because of his low weight. He was also rejected from the football team for that same reason.

To compensate for his disappointments, he turned to his childhood hobby of model airplanes and with the help of some friends, began building small motorized planes that could actually fly. Eventually this small group of young men saved enough money to actually rent a real plane, which they flew out of Palwaukee airport to Madison, Wisconsin and back. Elbert loved flying, and he and his friends dreamed of becoming a pilots. It was an expensive hobby to maintain, however, and it was also thwarted when their interests began to shift toward the opposite sex. “Girls with lapdogs got in the way,” Elbert says.

All of his friends began dating and got married just after high school. Elbert says that he dated several girls but never found the right one because “I didn’t try very hard.” In true George Bailey (It’s a Wonderful Life) fashion, he had “visions of traveling around the world a few times” or “owning a big business. Marriage wasn’t that important to me. I didn’t want to get tied down. But,” he says, “I never seemed to get around to much of anything.”

After high school, he spent the summer working on various farms in Wisconsin and Michigan, though it didn’t pay a lot. “The fishing is what drew me to want to work in Michigan,” he says. In the fall of 1931, he started at college and again tried to get into the R.O.T.C., but was again rejected due to weight. “I guess it was a good thing,” Elbert says, “because then the war broke out.” After college, he went on to get a master’s degree in journalism from Northwestern. From there he went to University of Illinois with the intention of getting his doctorate, but eventually grew tired of it and quit. He worked for various newspapers for several years until he quit those, too, saying that “journalism grew boring from sheer repetition.”

At that point, Elbert decided to take time off to travel, which had forever been his dream, but he didn’t get very far, as he soon ran out of money. “California is where everybody went and came back a star, but I never go around to it.” He never went to Europe as he had hoped. He sums up life in this way: “Life is like Christmas time when you get a new set of golf clubs and you think, ‘that’s for old men. I’ll put them away and dig them up later.’ But then I never did, and now it’s too late.”

After his brief travel stint, Elbert mostly worked odd jobs and lived at home, caring for his elderly parents, both of whom died of TB within two months of each other in 1956. After his parents passed away, he got a job as a researcher at a law firm and then went to Foundation Press, which later became Wolters Kluwer/CCH.

Elbert continued living in his parents’ house, never marrying, though he says he enjoyed being “Uncle Elbert” to his many nieces and nephews. “Kids like me,” he says. “I’ve always valued that. I’ve always been Uncle Elbert.” Elbert retired at age 72, and has continued to live on his own, pottering about his house in relative independence. He has two cousins, Bonnie and Lynn, living in the suburbs who have been driving into the city every week to check on him.

Sadly, in early 1996, his cousin, Lynn, found him unconscious on the floor. She called an ambulance, and he was taken to the hospital and diagnosed with lung cancer. Based on his prognosis and the fact that he has no one at home to care for him, his doctor recommended that Elbert be admitted to a nursing home. Bonnie and Lynn were reluctant to make that decision for him, but after talking with the hospital social worker, they decided that it would be the best place for him, especially as his house has become more and more rundown and dirty. Likewise, he had stopped eating while at home, despite the fact that both Lynn and Bonnie were bringing him food.

At the time the decision was made, Elbert was not fully conscious and therefore did not participate in the decision. Since his admission to the nursing home, he has become more alert and now wants to go home. He is having a hard time accepting why he has to be here and is angry and anxious most of the time, except when telling his story. Despite his depressed state, he is very humorous and bright when speaking and can easily make people laugh. It’s not hard to see why he was so popular with kids. The staff are trying to involve him as much as possible in an attempt to get him to accept his new home and have talked to him about the possibility of hospice care. His favorite thing to do so far, however, is reading the Chicago Tribune every day and watching the White Sox on TV.

(Originally written: January 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “I’ve Always Been Uncle Elbert.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

December 30, 2021

Despite Her Promises, She Never Appeared.

Sveva Boucher was born on November 10, 1913 in Winnipeg, Canada to Jean-Marie and Sylvia Boucher. Jean-Marie was born in Switzerland, and Sylvia was born in Germany. They met and married in Switzerland where Jena-Marie had a small farm. They began their family there, but at some point, they decided to immigrate to Canada. Jean-Marie found work at a creamery, which produced butter and cheese and processed milk, while Sylvia cared for their fourteen children: Tamara, Ulla, Tecla, Bastien, David, Vanda, Ingrid, Hugo, Yvette, Josephine, Igor, Adolph, Jeannette and Sveva. All of them lived to adulthood except Tecla and Igor, who died in a house fire.

Sveva Boucher was born on November 10, 1913 in Winnipeg, Canada to Jean-Marie and Sylvia Boucher. Jean-Marie was born in Switzerland, and Sylvia was born in Germany. They met and married in Switzerland where Jena-Marie had a small farm. They began their family there, but at some point, they decided to immigrate to Canada. Jean-Marie found work at a creamery, which produced butter and cheese and processed milk, while Sylvia cared for their fourteen children: Tamara, Ulla, Tecla, Bastien, David, Vanda, Ingrid, Hugo, Yvette, Josephine, Igor, Adolph, Jeannette and Sveva. All of them lived to adulthood except Tecla and Igor, who died in a house fire.

Sveva went to school until the eighth grade and then got a job as a maid in Winnipeg. Her sister, Jeannette, says that Sveva was always a “little bit different.” She wasn’t “backward,” Jeannette says, but “she had her own ways of doing things.” She was very independent. Jeannette seems to remember that she had “a beau for a time,” and that he proposed to her, but Sveva turned him down. She enjoyed reading and doing embroidery work, and on her one day off a week, she usually went to the movies or would walk in the park. “She was a real loner,” Jeannette says. “She didn’t have many friends, except maybe the other maids she worked with.”

At one point, however, Sveva’s older sister, Josephine, persuaded her to come visit her and her husband in Chicago. Sveva apparently loved Chicago so much that she decided to stay permanently and wrote a letter telling her parents the news. Sadly, she never saw them again.

Sveva was able to easily get a job as a maid for a very wealthy family on the north shore. Jeanette says that she doesn’t know much else about her life, as Sveva rarely wrote home. Likewise, the family did not hear much about her from Josephine, as they lived at opposite ends of the city, and Sveva was usually unwilling, Josephine reported, to spend the majority of her one day off traveling to the south side and back. As a result, they didn’t see each other that much.

In the 1960’s, Jeannette’s husband died suddenly, which caused Jeannette to go into a deep depression. She wrote to Sveva and begged her to come back to Winnipeg to live with her. By that point, Sveva had stopped being a maid and instead worked as a part-time office cleaner and lived in a studio apartment on Glenwood. Each time Jeannette wrote to Sveva asking her to come back to Winnipeg, Sveva would write back, saying that she would come. To Jeanette’s disappointment, however, Sveva would never turn up as promised.

Finally, Jeanette decided to pay for a telephone call to Sveva, begging her to come back. Sveva promised that she would and sounded eager to come, crying on the telephone to Jeannette that she missed her. The plans were all arranged then, and when Jeannette called the day before Sveva’s supposed departure, Sveva confirmed that she was all packed and ready to go. When Sveva failed to appear, yet again, however, Jeannette telephoned her, convinced that something terrible had happened. She was surprised when Sveva answered the phone. She demanded to know why Sveva had once again not shown up. Sveva’s only response was, “I guess I forgot.”

That was the last time Jeanette asked Sveva to come, concluding that something was mentally wrong with her sister. Josephine, meanwhile, had passed away in 1959, so Jeanette was no longer able to get news of Sveva through her. Jeanette tried her hardest, she says, to keep in contact with Sveva over the years, but it became apparent that as time went on, Sveva was becoming more and more confused and disoriented. Jeanette says that she wanted to come to Chicago to check on her, but she never had the money. Then, in 1986, Jeanette had a small stroke, which made traveling all but impossible. She continued to worry about Sveva until she got word that her sister had moved into an assisted living facility with the help of some neighbors who looked out for her.

Sveva was recently admitted to the hospital due to some infected sores on the bottom of her feet and has also been diagnosed with chronic brain syndrome. Because her condition now requires skilled nursing care, her doctor discharged her to a nursing home. Jeanette has been contacted and is overjoyed that her sister is being cared for properly. She has tried to talk with Sveva on the telephone, but Sveva does not respond.

For her part, Sveva is making a relatively smooth transition. She does not mind being around other residents and is very docile and compliant. She is extremely confused, however, and cannot even form coherent sentences. She participates in activities with assistance and seems to like music programs the most.

(Originally written: April 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Despite Her Promises, She Never Appeared. appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.