Michelle Cox's Blog, page 17

May 27, 2021

In and Out of Mental Institutions

Hattie (right) with her sister, May

Hattie Shirley was born on August 21, 1916 in Boise, Idaho to Orville Mayfield and Alberta Hass. Not much is known about Hattie’s parents except that when Hattie was a baby, they divorced. Alberta took the three children: May, Hugh, and Hattie and moved to Chicago, where she eventually met and married a man by the name of Clarence Woods.

Hattie went to high school and then attended business school where she became an accomplished typist. She worked for several years as secretary for a brewery in Chicago, where she met a quiet, bookish young man named Wilson Shirley. Wilson and Hattie married and had two children, but no one knows their names or where they are now. It is thought that the boy has since died, but that the girl is alive somewhere and married.

Besides her own two children, Hattie often cared for her sister, May’s, daughter, Norma. Norma was apparently a great favorite of Hattie’s. Norma would often come and stay with her Aunt Hattie and Uncle Wilson, and she and Hattie would make up all kinds of games to play, their favorite being “house.” Hattie would pretend to be “Mrs. Green,” and Norma would be “Mrs. Brown.” Norma laughs at how strange it was that she actually did grow up to become “Mrs. Brown,” having married a man named Paul Brown!

Norma reports that when she was about ten years old, she noticed a change in her Aunt Hattie that no one else picked up on. Something just seemed “different” about her, and Norma began to be afraid to stay there anymore. Norma suspects that it was the beginning of Hattie’s mental illness and subsequent stays in mental institutions, which she was in and out of for the rest of her life. Hattie was at some point diagnosed with organic brain syndrome and/or schizoaffective disorder and eventually lost all contact with her family. Her brother, Hugh, died, and May and her husband and Norma moved to Florida. It is unknown what happened to Wilson and their two children.

At some point, a State Guardian was appointed for Hattie, who then oversaw her various admissions to mental institutions over the years. Eventually, as Hattie aged, she was transferred to the Westwood nursing home in 1985, where she remained without incident for ten years. When she recently developed pneumonia, however, and was hospitalized, she refused to go back to Westwood upon discharge. No problem behavior was noted in her chart from Westwood, and the staff seemed puzzled at her refusal to come back, saying that they thought she liked it there. Her guardian decided, however, that perhaps Hattie was getting bored and restless in that environment and suggested that a change of facility might be good for her.

Hattie was then admitted to this current facility and seems to be making a very smooth transition. She is a very sweet, gentle woman who can carry on a conversation, though it often becomes nonsensical. Hattie does not remember much about her past, but she loves to make up stories about herself, which she delivers in a casual, nonchalant sort of way, which adds to the charm of them.

One of Hattie’s stories is that her mother, Alberta, gave her up as a baby to a Mrs. Lieberman, the administrator of the Westwood Nursing Home (where Hattie was previously a resident). Hattie relates that her mother had a very hard labor with her and that, after all that work, Hattie had come out rather ugly, which is why Alberta decided to give her up. When asked if Westwood was an orphanage at the time, Hattie replies that no, it was a nursing home and that yes!—she was raised in a nursing home! When asked about her occupation in life, she reports that she was Mrs. Lieberman’s “coffee girl” and that it was her job to run around and serve Mrs. Lieberman coffee all day. The only time she became distressed—to the point of tears—during her admission interview was when she said she tried to commit suicide at Westwood, which the staff and her guardian say is simply not true.

So far Hattie seems to be enjoying her new home. She does not really interact with the other residents but loves to dress up and put on makeup and to have her hair done at the facility salon. She has no family or friends who visit, but doesn’t seem to be aware of this, or, if she is, she doesn’t seem to mind.

(Originally written: March 1995)

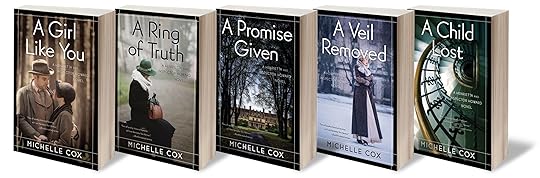

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post In and Out of Mental Institutions appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 20, 2021

“All I Have is Scraps!”

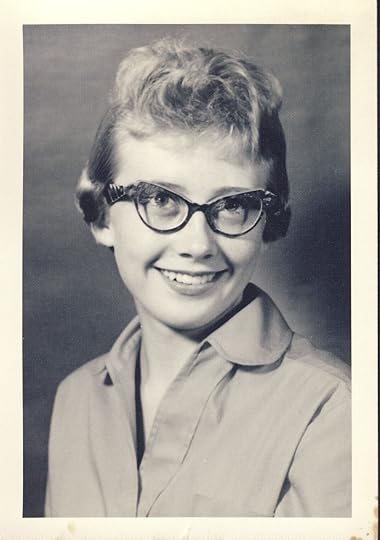

Caroline (right) with her sister, Effie

Caroline Alders was born on June 21, 1917 in Chicago to Fester Alders and Erna Hendricks, both Dutch immigrants who met on a ship to America in 1910. Fester worked in a meat-packing plant in Chicago, and Erna was a housewife.

Fester and Erna’s first child, a boy by the name of Ernest, died when he was just five years old of a “throat epidemic.” Caroline was born nine and a half months after Ernest’s death and was followed two years later by another girl, Eefje “Effie.”

Caroline graduated from high school, which she is extremely proud of, and then got a job as a bookkeeper at a small office in Chicago. When she was just nineteen, her father, Fester, slipped on a piece of fat at the meat-packing plant and hit is head on the ground. He suffered from some sort of internal hemorrhage for about two months before he killed himself.

Erna never really recovered from the shock of her husband’s accident and his subsequent taking of his own life. After that, her own health began to decline and she was eventually diagnosed with a heart condition. Right at about this time, Caroline was dating a young man by the name of Joseph Schultz, who worked as a law clerk and whom Caroline says she really loved. When he proposed to her, however, she turned him down, which broke both their hearts, she says. At the time, Caroline’s sister, Effie, was already married and living in Arizona, so Caroline felt it was her duty to stay and take care of her mother. Joseph apparently offered to have Erna live with them, but Caroline says that at the time, she did not think that the proposed arrangement would have been fair to him, so she remained resolute in her rejection of him. Years later, she heard that Joseph had been killed in the war, which she saw as a sort of justification of her decision. “It proves it wasn’t meant to be,” she says sadly.

Caroline continued to work at various small offices around Chicago for the whole of her adult life. She loved to read, and her only other hobby was taking classes at the YWCA at night. Caroline says they were college level classes, but she did not get any credit for them. She took many classes, she says, on anatomy and disease and biology and had a real fixation for a time on the various “tragedies” that befell her family over the years. She says that she was always trying to figure out what really happened to her father and her brother and why her mother suffered from heart issues. It is not clear whether she found all the answers, but she says she would have liked to have become a nurse.

When her mother, Erna, died in the early 1960’s, Caroline found herself alone for the first time. She lived for another thirty years in the same apartment on Pulaski Avenue in which she had grown up, working until she was 75. When she began experience some health problems herself, she decided to go and live with Effie in Arizona, whose husband had passed away several years before. After about a year, however, the sisters realized it was not going to work out; both of them were too set in their routines. Caroline then moved back to Chicago and got a garden apartment on Keystone. Her landlord, Mr. Rondowski, has been keeping an eye on her for the last three years and reports that she has been needing more and more help in the last six months or so. Increasingly, he became worried that he would go in some day and find her dead.

Apparently, that exact situation nearly happened just a couple of months ago when Mr. Rondowski went to check on Caroline and found her very ill in bed. He called an ambulance, and she was taken to the hospital and diagnosed with pneumonia. Given the fact that she has no family or friends to help her, Caroline’s doctor discharged her to a nursing home. Effie has apparently been notified, but she cannot come due to her own health problems.

Caroline, meanwhile, is recovering physically, but remains depressed and angry. She blames her current “miserable” situation on Mr. Rondowski, whom she believes was responsible for her placement here and feels betrayed by him. She constantly asks aloud, “Why have I been made to suffer?” and refuses to join in any of the home’s activities. She hates TV and will not talk with the other residents. She believes that the nurses are “trying to control me” and that “they keep me locked up.” She spends her time in her room, attempting to get her “affairs in order,” so that she can “get out of this place.” Apparently to that end, she is constantly writing notes to herself on little scraps of paper she keeps in the front pocket of her dresses. In fact, her room is a sea of notes, which she refuses to let anyone touch. “What can I say?” she asks. “I’ve had a terrible life. All I have is scraps.”

(Originally written: September 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “All I Have is Scraps!” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 13, 2021

“Just a Coal Miner’s Son”

Lou Dean (baby) pictured with his parents and siblings

Lou Dean Rogers was born on May 25, 1936 in a small town in West Virginia to Herman Rogers and Maxine O’Toole, who was originally from Virginia. Herman worked in a coal mine for forty-six years while Maxine cared for their four children: Herman, Jr., Ruby June, Bobby Ray and Lou Dean, though Bobby Ray died of a “sore throat” when he was five or six, Lou says.

Lou attended elementary and high school, but in order to avoid working in the mines like his father, he joined the marines as soon as he graduated. He served in the marines for nine years and fought in the Korean War. Upon being discharged and returning to the United States, he traveled around the country for a long time, trying to figure out what to do next. He finally settled in California and got a job at a factory called Continental Can. He stayed with it for a while before moving to Reno to become a black jack dealer. From there he decided to move to Chicago and got a job with the Park District.

Lou settled into Chicago and found an apartment on Belmont and somehow happened to meet a young woman by the name of Daisy Marshall, whom he eventually fell in love with and proposed to. Daisy worked as an executive secretary for a company on Addison, which Lou says she started working at when she was just seventeen. At the time of this writing, Lou claims she works there even still.

Lou and Daisy got married and had one daughter, Ramona. According to Lou, he and Daisy got along okay, but would have terrible fights whenever they drank, which was often. “We just couldn’t make it work,” says Lou. When Ramona was thirteen, they divorced, and Lou decided to go back to West Virginia, where his parents, Herman and Maxine, were still living. At that point, both of his parents were quite elderly and in need of a lot of help, so Lou went to live and care for them until they died within six months of each other.

Upon their deaths, “there wasn’t much” for Lou in West Virginia, so he returned to Chicago and got his own apartment and was even able to get his job back with the Park District. He hasn’t had many hobbies besides watching sports and comedies on TV and does not have many friends or a big social circle. In 1987, he fell at work, supposedly due to drinking on the job, and was hospitalized. Later he was diagnosed with alcoholism. After that, he lost his apartment and had to sometimes resort to sleeping on the street. From time to time, he had enough money to get a room at a boarding hotel.

Lou has continued over the years to be admitted in and out of the hospital because of falls or complications due to his alcohol consumption. About a year ago, he was discharged to a nursing home by his doctor, where he was able to “dry out.” Lou eventually checked himself out of that facility, however, and went back to living in a rented room. He says he stayed sober for a while but then went back to drinking. Recently, he was again admitted to the hospital, this time to Swedish Covenant, for internal pain. His doctor again discharged him to a nursing home and warned him that if he checks himself out again, he will drop him as a patient.

Lou says he understands what is at stake, but finds it very hard to not drink. He says he has always been a “jittery” person. “I’m always very nervous inside,” he says. Certain things never bothered him, he relates, such as watching his parents die or witnessing men killed in battle. But small things set him off, he says. He admits that he’s always been a heavy drinker, but doesn’t think this is a problem. He likes the current facility, but he doesn’t want to stay because he’s not allowed to drink.

Lou’s daughter, Ramona, visits occasionally, but seems to be keeping an emotional distance. According to Lou, he tried to contact her over the years but that Daisy “poisoned” her mind against him. Daisy has not spoken to him for years, so Ramona has agreed to be listed as his next of kin. She has told the staff, though, that she is not interested in being overly involved in his care.

Meanwhile, Lou seems to be making a relatively smooth transition to the home. He enjoys watching sports on TV with some of the other male residents, but sometimes complains that everyone here is “too old.” He tried bingo, but says they go too slow. He claims to be waiting to see what will happen between himself and his doctor and for now is just “letting it ride.” Besides what his soured relationship with Ramona, Lou says he has few regrets in life. “I’m just a coal miner’s son in the end,” he says, “and I didn’t do too bad, if you think of it that way.”

(Originally written: September 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Just a Coal Miner’s Son” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

May 6, 2021

“It Either Drives You Apart, or It Brings You Together”

Katie Bohler was born on March 27, 1906 in Chicago to Edward Moran and Bridget Berne, both born in Ireland. Before Edward, Bridget was was married to another man, Patrick Cooney, while still in Ireland and had two children with him. At some point, she and Patrick decided to immigrate to America with their two children, Eamon and Mary, but Patrick died shortly after arriving here. Bridget had a cousin in Chicago, so she made her way there with Eamon and Mary in tow and eventually met and married Edward Moran. Katie was the only child born of that marriage.

Katie Bohler was born on March 27, 1906 in Chicago to Edward Moran and Bridget Berne, both born in Ireland. Before Edward, Bridget was was married to another man, Patrick Cooney, while still in Ireland and had two children with him. At some point, she and Patrick decided to immigrate to America with their two children, Eamon and Mary, but Patrick died shortly after arriving here. Bridget had a cousin in Chicago, so she made her way there with Eamon and Mary in tow and eventually met and married Edward Moran. Katie was the only child born of that marriage.

Over time, Bridget and Edward saved enough money to buy a candy shop at Hermitage and 50th, which they both spent years working in. Edward was actually the cook/baker, and Bridget worked the counter. Like her older step-siblings, Katie graduated from eighth grade, a fact she is very proud of, even to this day. Not long after she finished school, however, her father, Edward, died, though no one can remember of what. Bridget managed to keep the candy shop running on her own, with Katie helping in the shop as well as getting a part-time job at Sears & Roebuck. Eamon and Mary were already grown and married at the time of Edward’s death, so they weren’t much help in the shop.

When she was just seventeen, Katie married Adam Bohler, whom she knew growing up in the neighborhood. Adam was of German descent and had gone to school until the 5th grade before quitting to get a job. Eventually, he found a steady employment working as a mechanic for the city of Chicago, a job he kept until he retired at age sixty-five.

Once they were married, Katie stayed home to care for their children, though only two of their five lived. Their oldest, Harry, died when he was just two years old of a strep infection. Katie got pregnant almost immediately after, but she miscarried that baby at six months. It was another boy. Their third child, Rose, lived to adulthood, but she died at age twenty-two giving birth. The baby died, too. Only their two youngest daughters, Lillian and Eileen, lived.

Katie and Adam apparently had a good marriage and loved each other very much. Katie says that when you have so many sad things happen, “it either drives you apart, or it brings you together.” Katie and Adam did not go out much, preferring to stay home most of the time. Adam loved watching sports on television and was a season ticket holder for the White Sox. Katie had few hobbies except knitting and embroidery, though she was involved in many groups at church. Her daughter, Eileen, says that her mother had a reputation at church for “never saying no,” and could always be counted on to bring a hot dish to any event. For many years, she even coordinated all the funeral dinners at St. Joseph Catholic Church, which was very near their home. Eileen says that they have a whole closet full of embroidered pieces that Katie worked on over the years but which no one now seems to want. Both Eileen and Lillian claim to be downsizing their own homes and don’t want extra things, nor do any of the grandchildren want them.

Sadly, Adam passed away in 1987 of cirrhosis of the liver, though it was not caused from drinking, apparently. Katie remained in their house, pottering about and still attending various women’s groups at church until October of 1993, when she had a stroke and was hospitalized for several weeks.

When she was finally released back home, Eileen and Lillian hired a housekeeper to come in and help her, but Katie proved to need too much care, especially as she seemed very confused at times. She would often forgot who the housekeeper was and would shout at her to get out of the house. Not knowing what else to do, Eileen and Lillian sat down with Katie and proposed admitting her to a nursing home. They say that Katie was very accepting of the decision at the time, but now, however, she doesn’t seem to remember that conversation. She believes she is only here until her “feet heal,” even though there is nothing currently wrong with her feet. She says that she is resigned to make the best of her situation until that happens, when “Eileen will come to take me home.”

Katie is a very pleasant woman who loves to laugh. She is confused at times, but on other occasions, she seems sharp and enjoys interacting with other residents. She is trying to start an “Irish Singing Club,” which Eileen finds odd, considering her mother was never a big singer in the past. Still, Eileen is grateful that her mother is interested in something, however peculiar it seems. Someone from the family visits at least weekly, which Katie looks forward to and enjoys, though sometimes these family visits don’t end well when the relative leaves and does not take her with them. Overall, however, Katie she is making a great transition.

(Originally written: December 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “It Either Drives You Apart, or It Brings You Together” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 29, 2021

“He Can Walk Because of Me.”

Thomas Bisky was born on June 30, 1910 in Brooklyn, New York, to Stefan Brzezicki and Magda Chmiel. Stefan and Magda were both born in Poland where they met and married. Not much is known about what their life in “the old country” was like, except that Stefan served in the army for a time. At some point, Stefan and Magda managed to immigrate to the United States, where their married name “Brzezicki” was recorded as “Bisky” at their port of entry.

Thomas Bisky was born on June 30, 1910 in Brooklyn, New York, to Stefan Brzezicki and Magda Chmiel. Stefan and Magda were both born in Poland where they met and married. Not much is known about what their life in “the old country” was like, except that Stefan served in the army for a time. At some point, Stefan and Magda managed to immigrate to the United States, where their married name “Brzezicki” was recorded as “Bisky” at their port of entry.

With their new name, the Bisky’s settled in Brooklyn, New York, where Thomas was born, and then moved to a farm in Hawley, Pennsylvania, where Stefan worked as not only a farmer, but a coal miner as well. Magda cared for the children, but Thomas can’t quite remember how many there were. Besides himself, he remembers Gladys (who legally changed her name to Susan at age seventy), Albert (who went by Frank), Charles and Florence. Thomas’s son, Walter, claims that there was also a fourth brother whom no one ever talks about, a “black sheep,” who lost contact with the family long ago. And there may have been two more children who died during the flu epidemic, Thomas says, but he isn’t sure.

Thomas went to school through the eighth grade and then started working in the mines with his father. He soon tired of this, however, and got a job in construction instead. Jobs were scare, though, so he moved to New Brighton, Pennsylvania to find work. When he first got to New Brighton, he stayed in a boarding house and was befriended by another young man, Cal Trenfor, who was staying there. Cal and Thomas became friends, and Cal eventually got around to introducing Thomas to his sister, Ethel. Thomas and Ethel began dating and married soon after. They got an apartment in nearby Elwood City and then bought a house in New Brighton in 1949, where Thomas has since lived all these years.

Thomas got a job at the B&O Steel Mill and worked there for 31 years until he retired. He and Ethel had two sons: Thomas, Jr. (Tom) and Walter. Apparently, when Walter was born, he was a breech birth and born with a broken shoulder and crooked feet. Thomas still tears up when telling the story. At the time, Thomas was devastated that his new little son was born “deformed,” especially when the doctor said that he would have to go to a special home to live. Thomas refused to send his son away and instead begged the doctor to try to do something himself. Reluctantly, the doctor agreed to try to put special casts and braces on Walter’s legs and feet. Shockingly, over time, Walter’s legs did indeed straighten out, as much to the doctor’s amazement as to everyone else’s. Walter was then deemed a “normal” boy by the doctor, who insisted on proudly displaying him to his colleagues. But Thomas also took much pride in the part he played for his son, often saying, “He can walk because of me!”

Thomas apparently did not have many hobbies, except whittling. Also, he and Ethel loved to go dancing on Saturday nights. Both of their boys grew up and moved away: Tom to Virginia Beach and Walter to Chicago. In 1989, Ethel passed away from cancer. Thomas continued living in the house alone, spending his time pottering about and doing a little bit of gardening. Recently, however, both Tom and Walter began to notice that their dad was seeming more and more confused when they would call him on the telephone. Also, he was sounding more and more depressed and was rarely leaving the house. It just so happened that right about this time, Walter’s wife, Linda, was looking for a nursing home for her mother and suggested that maybe Walter should arrange for Thomas to be admitted to the same facility.

At first, Thomas was resistant to leave New Brighton to move into a nursing home in a different city, but Walter assured him he would visit daily. Thomas agreed, then, and the house that he and Ethel had lived in for over forty years was sold. Thomas seems to be making a relatively smooth transition to his new home, though he is sometimes confused and forgets where he is. He is quiet and shy and seems nervous most of the time, though he was a wonderful sense of humor when in conversation. He will join in activities, but only when encouraged to several times. His favorite is “Big Band Hour,” followed closely by bingo.

Walter has so far kept his promise and visits daily, often bringing his own children or grandchildren along, and which Thomas really looks forward to. Despite the fact that they have lived apart for so many years, they seem to share a deep love for each other. When asked about Ethel, Thomas still seems sad but usually catches himself and says “at least I have Walt.”

(Originally written: December 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “He Can Walk Because of Me.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 22, 2021

Left For Dead

Casimir Winogrodzki was born on February 20, 1939 in Poland to Adalbert Winogrodzki and Zita Sadowski. Adalbert was a farmer, and Zita cared for their six children: Bartholomew, Viola, Emil, Henryk, Casimir, and Jan. Casimir went to school until the equivalent of the eighth grade and then became apprenticed to a baker in the same small town where he had been born. His specialty became cakes, and he worked in “cakes” for ten years before branching off into “breads.”

Casimir Winogrodzki was born on February 20, 1939 in Poland to Adalbert Winogrodzki and Zita Sadowski. Adalbert was a farmer, and Zita cared for their six children: Bartholomew, Viola, Emil, Henryk, Casimir, and Jan. Casimir went to school until the equivalent of the eighth grade and then became apprenticed to a baker in the same small town where he had been born. His specialty became cakes, and he worked in “cakes” for ten years before branching off into “breads.”

Casimir worked at that same bakery for thirty-two years and got to know many people, including the sister of a fellow baker, who would come in often to visit her brother, Felix. The girl’s name was Ursula Szewc, and before long, Casimir fell in love with her. They married when he turned twenty-one and she was twenty-three. They bought a house in the town, Casimir working in the bakery and Ursula working in the local health-care center. Besides baking, Casimir had a real talent for woodworking and loved carving little toys, which he would often give to his favorite customers at Christmas time to give to their children. He also loved music and winter sports, which he says were popular in that part of Poland. He and Ursula eventually had two children: Elizabeth and Jan.

Casimir remained relatively healthy until he was in his fifties and then began experiencing terrible pains in his back. After seeing many different doctors, it was finally determined that his back issues were job-related, and he was therefore put on disability.

At around this time, Ursula began receiving letters from her mother, Anna, in America to say she was having a lot of health problems herself. Ursula’s mother had been born in America, but raised in Poland. Anna married and had a family in Poland, but once all of her children were grown and settled, she decided to return to America, as she was technically an American citizen. Ursula’s father, of course, went with her, but he passed away after only about five years. Anna remained in Chicago, where they had settled, on her own, living independently, until she fell and was found it difficult to convalesce alone. Thus, she began to write to Ursula, asking her to come.

Casimir and Ursula finally decided to go for a visit and liked America so much that they decided to immigrate in 1994. They are are hoping that their children and grandchildren will also be able to come over and live at some point.

In the meantime, Casimir decided to try to get a job at a bakery again and was successful at getting hired at a shop on the South Side near Archer and Sacramento, near where they lived. Unfortunately, however, he became the victim of a crime one night, which changed his whole life completely.

Casimir had just finished his shift and left work at 3:00 am, as was usual for him, and began to walk home. Suddenly, he was approached by a gang of five or six men who attempted to mug him. Casimir called for help, so the men beat and kicked him into unconsciousness. They then put him in a car and drove to a forest preserve, where they dumped his body and left him for dead. He was found by the police the next day and was rushed to the hospital.

Meanwhile, Ursula was in a panic because Casimir had not come home. She called the Polish Alliance, who called the police. Eventually, after three long days, she discovered that he had been admitted to Christ Hospital in Oak Lawn. Casimir remained there for over six weeks, trying to recover from a severe brain injury. Ursula enlisted the help of a friend of a friend from the Polish Alliance, George Gorski, who stepped in to help the Winogrodzkis navigate the medical system and to help make arrangements.

When Casimir was well enough to be released from the hospital, George and the discharge staff convinced Ursula to put Casimir in a nursing home until he could hopefully regain some strength and memory. After only a few weeks in that facility, however, George recommended moving him to a nursing home on the North Side of Chicago, which had predominantly Polish and Czech residents and staff, hoping it would help Casimir’s memory. Ursula reluctantly agreed, though this made visiting him very difficult, as their apartment was on the South Side. To solve the problem, she decided to move herself and her aging mother to the North Side to be closer to the facility. She is now able to visit him daily and even brings him home with her on the weekends.

Casimir has made a relatively smooth transition to this current nursing home and seems to be making progress mentally each week. He says he is no longer angry at his attackers and has forgiven them, though he suspects that Ursula has not. Casimir says he likes it at the nursing home and enjoys talking with the other Polish residents. Because he is considerably younger than them, he enjoys doing little favors for them and helps transport them to the various activities offered by the home.

(Originally written: September 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Left For Dead appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 15, 2021

“I Cured Myself of Cancer!”

Verla Swanson was born on March 29, 1942 in Albany, NY to Lev Reznik and Klara Grinberg, Russian Jews who had also both been born in Albany. As a young boy, Lev started out working at a company that fixed tires, but when the company went broke, he began volunteering as a prep cook in hospitals and nursing homes until he was offered a paid position. He then moved on to work for the State of New York as an operator for their addressograph, which was a machine invented for printing addresses on envelopes. Klara, meanwhile, stayed home to care for their three children: Rose, Verla, and Gary. When the kids became teenagers, however, Klara went back to work at the same men’s clothing store she had worked at before she got married to Lev. In later years, she also got a job working for the State of New York, processing insurance claims.

Verla Swanson was born on March 29, 1942 in Albany, NY to Lev Reznik and Klara Grinberg, Russian Jews who had also both been born in Albany. As a young boy, Lev started out working at a company that fixed tires, but when the company went broke, he began volunteering as a prep cook in hospitals and nursing homes until he was offered a paid position. He then moved on to work for the State of New York as an operator for their addressograph, which was a machine invented for printing addresses on envelopes. Klara, meanwhile, stayed home to care for their three children: Rose, Verla, and Gary. When the kids became teenagers, however, Klara went back to work at the same men’s clothing store she had worked at before she got married to Lev. In later years, she also got a job working for the State of New York, processing insurance claims.

Verla attended high school and college and got a B.S. in education, which she has supplemented over the years with 60 additional credit hours. Her first teaching job after college was working as a PE teacher, but she later began working with drop-outs as both a teacher and a counselor.

Verla got tired of her life in Albany, however, and decided to move to San Francisco, where she met her future husband, Tad Swanson. Tad was also a teacher, and, after they were married, he and Verla opened up a math and reading center for kids and adults. They both apparently enjoyed their work at the center for several years before they then decided to move to Hawaii with Tad’s four kids from a previous marriage. In Hawaii, they bought a clothing shop, which Verla ran, and an ivory scrimshaw shop, which Tad ran. The ivory shop was a huge success, which made the Swansons a lot of money. Tad became a very powerful, influential figure in town, Verla says, which “went to his head.” She also says that Tad and all four of his grown children began using cocaine on a regular basis. Eventually, Verla couldn’t take it anymore, and she divorced Tad.

Alone now with few friends, as her whole life had been devoted to working at the two shops, she began frequenting dance clubs and one night at the Hyatt, met Randy Rossmoor, a golf pro. The two fell in love, and Randy convinced Verla to move to Chicago with him, where he was from originally. Deciding that there was nothing left for her in Hawaii, Verla agreed and moved to Chicago with Randy. There they bought a Fantastic Sams, but it went out of business. When the business failed, Verla and Randy broke up, too, but they remained good friends. “We were better as friends than as a couple,” Verla explains.

Eventually, however, Randy stopped calling altogether, which threw Verla into a depression that lasted several years. Finally, she decided to go to massage therapy school. She graduated and opened her own shop and was mildly successful until 1992, when she was diagnosed with breast cancer, which she believes was caused by the horrible stress of her divorce. “It took me ten years to get over Tad, and it weakened my immune system.” She had a lumpectomy, which she says further “killed my immune system. I was much healthier and stronger before the operation.”

After she recovered from the surgery, Verla says she went back to all of her normal activities, including rollerblading, which was her main hobby. She never gave cancer another thought, she says, and assumed that the surgery had taken care of it. She was horrified then when it reappeared a year later. She read somewhere that “scar tissue breeds cancer cells,” so she concluded that her lumpectomy scar was the source of the recurrent cancer. She refused to have her breast removed, which is what the doctors were suggesting, and also refused to have X-rays, for fear that they would “irritate the cancer.”

Instead, Verla decided to travel to a center in Indianapolis, Indiana, where she underwent “drippings,” which she describes as some type of IV therapy for cancer. From there, she traveled to another center in Houston, Texas for a similar type of IV therapy. “They ruined my arms,” Verla complains and says that they “popped the veins in both arms in one day.”

Disgusted and depressed, she left Houston and returned to Chicago. She gave up all hope in traditional medicine, feeling betrayed by all of the doctors she had seen thus far. Instead, she decided to read all she could about cancer so that she could come up with her own plan of treatment, which turned out to include massage therapy and a strict diet of raw food.

Verla fully believes that she cured herself of cancer using these techniques and that her cancer only returned because she was in a car accident in 1995. Initially, she thought she had merely sprained an ankle in the accident and gave herself massages to heal it. The pain she was experiencing grew worse, however, and began travelling up her leg to her buttocks. Unable to give herself effective massages, she asked other message therapists to come to her house to massage her, which they were willing to do at first, but then dropped off one by one.

Alone and suffering, she finally got someone to come out and give her a spinal message, which caused her to not be able to move her left side. Desperate, she called an acupuncturist to come to the house to try to correct the damage from the spinal message, but it only made things worse, as afterwards she was unable to move her right side either. Eventually, however, she improved a little and was able to hobble around her house. Later it was discovered that she had actually fractured her spine in the car accident and that the situation was made worse by “therapists who didn’t know what they were doing,” Verla says.

Over the next several months, Verla continued to decline, so she moved to a new apartment that was more handicap-friendly and got a caretaker to come in every so often to help her. During all of these health problems, Verla somehow unfortunately allowed her medical insurance to expire and was therefore burning through her savings rapidly.

At a colonic enema clinic, she met Joe Sanchez, with whom she became good friends. Verla says that Joe was very supportive of her, but not financially, even when she directly asked him for money. Eventually, Verla ran out of money entirely and admitted herself into a hospice house. The staff there contacted Verla’s family back in New York, with whom she had only erratic communication over the years. Her sister, Rose, and her brother, Gary, flew out to see her. “They did a lot of nice things for me while they were here,” Verla says, “but they only gave me $150.00.” Verla had asked them for money so that she could continue her regime of message therapy and “live” vegetable juices, but they refused.

About a month ago, the hospice house discharged her to a nursing home, where they thought the care would be more appropriate to Verla’s needs. Verla, however, is having a hard time adjusting. She demands constant attention of the staff, and if she does not get it, she cries or continuously pushes her call bell, sometimes in 10-minute intervals. She is demanding message treatments, which the home does not offer, and a diet only of freshly squeezed—“live”—juices of fruits and vegetables. When told this is not a sustainable option in this facility, she became very upset, though she has begun recently to eat cooked food, which she says she hates, after eating only raw food for three years. She also does not accept the fact that she has terminal cancer. “I’m not ready to die,” she says. “I don’t see any physical reason why doctors think I have cancer,” she adds, and points to the color and softness of her skin as well as the color of her veins to prove that she is cancer-free, though to everyone else she appears to be wasting away. “I want to walk again and be a normal person,” she says. “I know what has to be done, but I have no resources.”

Because she is significantly younger than the rest of the residents, she refuses to mix with them or join in any activities. “They’re all old!” she says. Occasionally, her friend, Joe, shows up to visit, but she is “disappointed by him, too.” Meanwhile, the staff are trying their best to find interesting things for Verla to do.

(Originally written June 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “I Cured Myself of Cancer!” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 8, 2021

“A Gentle Giant”

Robert “Butch” Baumgartner was born on May 25, 1915 in Pound, Wisconsin to Moritz “Morrie” Baumgartner and Maria Dreher, both immigrants from Germany. Moritz owned a farm in Pound, but he also worked as a stone mason to bring in extra money. Maria cared for their nine children: Michael, Meinhard, Nora, Otmar, Samuel, Rebecca, Robert (Butch), Sonia and Sieger.

Robert “Butch” Baumgartner was born on May 25, 1915 in Pound, Wisconsin to Moritz “Morrie” Baumgartner and Maria Dreher, both immigrants from Germany. Moritz owned a farm in Pound, but he also worked as a stone mason to bring in extra money. Maria cared for their nine children: Michael, Meinhard, Nora, Otmar, Samuel, Rebecca, Robert (Butch), Sonia and Sieger.

Butch was apparently a very intelligent, quiet boy with “a great mind.” He was apparently “a whiz” with numbers and could “add numbers in his head faster than a machine could.” But he was also good with languages and words as well. He learned German from his parents, of course, but he also learned Polish just by speaking to the Polish neighbor kids on the farm next to theirs. He apparently loved to read, and if he was ever missing as a child, his family knew to look for him under a tree somewhere on the farm, where he could always be found with a book.

Butch graduated from high school and went on to take some college classes to learn accounting. He continued working on the farm with his father and brothers, though, until World War II broke out. At the time, he was twenty-six and saw this as his chance to “get off the farm.” He traveled to Chicago to join the air force, but they told him he was two months too old, so he “went next door” to the army and joined up. He served in the South Pacific for almost five years.

While he was away at the war, Butch’s sister, Nora, got married and moved to Chicago with her new husband. When Butch was discharged, he went to stay with them rather than return to the farm in Wisconsin. He found a job relatively quickly which utilized his previous accounting skills.

Not long after he got a job, Nora and her husband, Ed, decided to set Butch up on a blind date with a friend of Ed’s from work, a woman by the name of Lydia Caspari, who was of Swiss and English descent. The four of them went out on a double date, and Lydia and Butch really hit it off and began dating in earnest. After only a few months, they wanted to get married. Lydia’s parents were not in favor of such a hasty marriage, but they eventually gave in. Butch and Lydia were married, then, at Pilgrim Lutheran Church and went on a honeymoon to Niagara Falls. When they returned, they moved in with Lydia’s parents, who owned a two-flat on Winchester. Lydia’s sister and her husband lived in the upstairs apartment, and Lydia, Butch and Lydia’s parents lived in the downstairs apartment.

Butch changed jobs a number of times until he found a position in the accounting department of ABC printing on Elston Avenue, where he remained until he retired at age sixty-eight. Lydia worked as an office manager at Grainger for over forty-seven years, even after having two children, Tom and Bernice. Lydia was loathe to give up her job, so when her sister, still living in the upstairs apartment, offered to watch the children, Lydia quickly agreed. It was an arrangement that seemed to suit everyone, as her sister was unable to have her own children and loved taking care of Tom and Bernice.

Lydia and Butch continued living in the two flat, even after Lydia’s parents died. Butch was a quiet man who did not like to socialize much, Lydia says. He was a real “outdoorsy” kind of man, who loved hunting and fishing and playing sports. In fact, after only a couple of years of being married, Butch and Lydia bought a cottage in Silver Lake, Wisconsin, where they often escaped to on weekends. It was a place Butch loved to go to, not just to hunt and fish but to read as well, a pastime he enjoyed his whole life.

Though he was happiest alone or with Lydia or a few close friends, Butch apparently felt the need to give back to the community to a certain extent. He joined the VFW in 1954 and eventually became the commander. He also served as the treasurer of his church for many years. He was a man with many interests and hobbies and could talk about anything. He was rarely stressed, Lydia says, and was very non-confrontational, despite being a big man. He never complained and didn’t like to argue with people. He was “a real gentle giant,” Lydia says.

When Butch retired, he and Lydia spent more and more time up at the cottage. In the early 1980’s, however, Butch began experiencing health issues for the first time in his life and was eventually diagnosed with Parkinson’s. Lydia, who continued working until 1991, has been caring for him as the disease has progressed, but lately it has become too much for her. After much persuasion, Tom and Bernice finally convinced her to put him in a nursing home.

Butch is not very responsive due to the progression of his disease, making it hard to assess his adjustment to his new surroundings. He will open his eyes if his name is called, but otherwise, he is non-communicative. Lydia is having a very hard time, however, and is considering admitting herself to the home so that she can be closer to him. She does not seem to grasp that his condition is terminal. “We had a great life together,” she says. “I don’t want it to be over.”

(Originally written: August 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “A Gentle Giant” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

April 1, 2021

“She Was Happiest With Children”

Zuzka “Susan” Vacek was born on July 31, 1902 in Bohemia to Adam and Bela Bobal. Adam worked as a farmer, and Bela cared for their eight children: Berta, Zuzka, Ambroz, Erik, Euzen, Vera, Klement and Ladislav. Zuzka went to school until about the equivalent of eighth grade and then quit to help her mother with the housework and caring for all the children, a task she apparently didn’t mind, saying that she preferred that to having to go to school.

Zuzka “Susan” Vacek was born on July 31, 1902 in Bohemia to Adam and Bela Bobal. Adam worked as a farmer, and Bela cared for their eight children: Berta, Zuzka, Ambroz, Erik, Euzen, Vera, Klement and Ladislav. Zuzka went to school until about the equivalent of eighth grade and then quit to help her mother with the housework and caring for all the children, a task she apparently didn’t mind, saying that she preferred that to having to go to school.

In her teen years, Zuzka’s older sister married a boy from their village by the name of Josef Chalupa. Not long after their wedding, Berta and Josef surprised the family by immigrating to America. They settled in a community called Cicero, just outside of Chicago.

Zuzka remained behind to help her parents, but decided, after her twenty-fifth birthday and much soul-searching, to join Berta and Josef in America. Adam and Bela were reluctant to let her go on her own and tried to persuade her brother, Ambroz, who was closest to her in age, to go with her. But Ambroz had met a young woman at this point and wanted to stay and marry her. Plus, he had a good job on a neighboring farm, and he didn’t want to give it up. Erik or Euzen were not a good option, either, because Adam depended on them to help him with his own farm, and Klement and Ladislav were too little.

Adam and Bela thus tried to talk Zuzka out of going, but her mind was made up. Finally, after much arguing between them all, Adam and Bela agreed to let Zuzka go, and so she set off on her own in the autumn of 1927. She traveled alone on the ship to New York and then made her way to Cicero by train, where she was eventually reunited with Berta and Josef. She lived with them and found a job at the Bohemian Orphanage on Foster Avenue in the city, a job she was good at after caring for all of her siblings over the years. Not only was she a hard worker, but she was supposedly always happy and friendly with the children at the orphanage and came to be much loved there.

Berta and Josef already had three children by the time Susan (as she was called in America) came to live with them, so they did not go out much. They were part of a Czech organization in Cicero, however, and often attended dances at the meeting hall. Susan, of course, would go along with them, and eventually was introduced to a man by the name of Stephen Vacek, who had also been born in Bohemia. Stephen was a widower with two sons, Frank and Paul, and worked as a tailor.

Stephen asked Susan to dance and later, at the end of the evening, nervously asked her out on a date. He thought her “the most beautiful girl he had ever seen.” Bashfully, she accepted. Stephen and Susan began dating in earnest, then, and married the following year. Susan moved into his house in Berwyn and took on the role of mothering Frank and Paul, both of whom she grew to love as her own sons. Stephen and Susan had one child together, a little girl they named Lucy. Susan said she wanted more children, but none ever came.

When the depression hit not long after their marriage, Stephen lost his job. After months of searching, he finally found work as a milkman, but it was on the south side of Chicago. Accordingly, then, the family moved. Upon marrying Stephen, Susan had given up her job at the orphanage to stay home and keep house and care for the children, but after the depression hit and the subsequent move to an apartment on the South Side, she needed to bring in some money. She eventually did find a job as a sewing machine operator on the night shift in a factory that made all types of men’s uniforms.

Susan and Stephen had a very good life together, says their daughter, Lucy. “Mom was always a happy person. Nothing seemed to get her down, and she was interested in everything.” She loved to garden, cook, bake, sew, sing and dance, among other things. Her real joy in life, however, says Lucy, was children. “She had a real gift. She would have made a great teacher.”

Sadly, in 1958, Stephen, significantly older than Susan, passed away of “natural causes.” After Stephen died, Susan decided to move back to Cicero where Lucy had returned to live, now with a husband and four children. Susan got a job in a shop in Cicero and continued working until she retired in 1972 at age 70. When she wasn’t working, she spent a lot of time watching her grandchildren and also became very involved in the Czech community. She joined many Czech clubs and lodges and was even a delegate on the Board of Directors for the Bohemian Home, the orphanage where she had once worked that had since been converted to a nursing home. She still enjoyed all of her old hobbies, as well, and once she retired, she began to do some traveling, too.

As the years have gone on, however, Susan has become more and more forgetful and confused. When she began wandering in the neighborhood, Lucy felt she had no choice but to put her in a nursing home. It broke her heart to do it, she says, but she couldn’t always be home to make sure her mother didn’t slip out of the house. Lucy chose a local nursing home in Cicero because it was close and convenient, but later felt guilty that she had not taken her mother to the Bohemian Home, which had been such a big part of her life.

So, only after six months of being in the other facility, Lucy transferred Susan to the Bohemian Home, where she happily made a very smooth transition. Though she is confused, she enjoys speaking Bohemian with other residents and loves the music and the Bohemian food. She is a very sweet, kind, compliant lady who definitely likes to laugh. She is able to walk without assistance and can always be seen carrying a baby doll in her arms, which she seems to think is real. She says it is one of Lucy’s children that she is “minding” while Lucy is away at work. No one has the heart to tell her otherwise, as she seems happy to again be caring for children here at the Bohemian Home, where she first started her life in America as a young immigrant girl all those years ago.

(Originally written June 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “She Was Happiest With Children” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 25, 2021

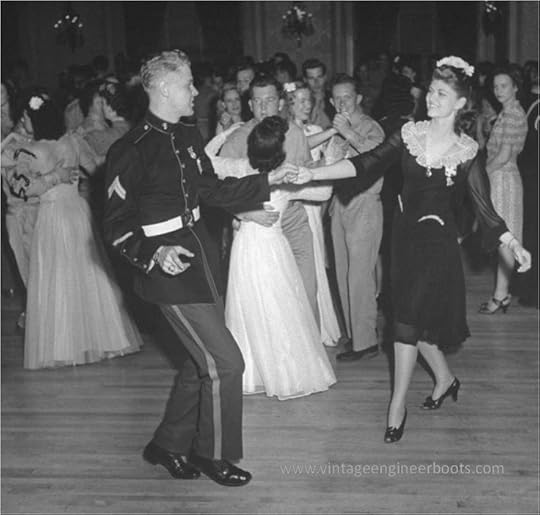

Eddy Howard and His Big Band Played at Her Wedding!

Kristina Abate was born on September 15, 1921 in Chicago to Swedish immigrants, Anders “Andy” and Cecilia Gerhardsson. Anders worked for the Chicago Tribune in their distribution department, and Cecilia cared for their eight children: Adolf, Emilia, Pelle, Judith, Hanna, Torgny, Walter and Kristina. All of them lived to adulthood except Hanna, who died of the flu as a baby. As the youngest, Kristina was very spoiled by her brothers and sisters, all of whom were much older than her. In fact, she spent most of what seemed to be a happy childhood playing with her nieces and nephews, who were more like siblings or cousins to her.

Kristina Abate was born on September 15, 1921 in Chicago to Swedish immigrants, Anders “Andy” and Cecilia Gerhardsson. Anders worked for the Chicago Tribune in their distribution department, and Cecilia cared for their eight children: Adolf, Emilia, Pelle, Judith, Hanna, Torgny, Walter and Kristina. All of them lived to adulthood except Hanna, who died of the flu as a baby. As the youngest, Kristina was very spoiled by her brothers and sisters, all of whom were much older than her. In fact, she spent most of what seemed to be a happy childhood playing with her nieces and nephews, who were more like siblings or cousins to her.

Unlike any of her siblings, however, Kristina attended high school and then went on to beauty school. She graduated and became a hair dresser at a little shop on Ainslie. Kristina was a very social person and had many friends. She loved movies, music and dancing, and often went to the Aragon and the Merry Gardens to dance. She had many boyfriends, but it wasn’t until one of her regular customers introduced her to her brother, Peter Petrauskus, that she began to be serious.

Peter’s family were Lithuanian immigrants, but, like Kristina, he had been born in Chicago. Peter worked at the Brach Candy Factory as a machinist, but shortly after they met, the war broke out and he soon found himself in the marines. Before he shipped out, Peter asked Kristina to marry him, and she said yes. Though the wedding was very quickly put together at St. Matthias, all of Kristina’s older brothers and sisters managed to turn it into a big affair with a dinner and a dance, and they even got a well-known big band to play as a surprise for the young couple. Kristina’s older brother, Walter, was a musician on the side and thus knew a lot of bands, some of them rather famous. Walter, it seems, called in a couple of favors and was able to secure Eddy Howard and his big band to privately play the wedding! This was quite a coup, as Eddy’s Chicago shows at the Aragon, The Edgewater Beach Hotel and the Palmer House were frequently broadcast on WGN, and they were a nationally known band. Kristina, to say the least, was absolutely thrilled and talked about it for years after as the highlight of her life.

Unfortunately, the young couple only had a weekend together and went to Rockford, Illinois for their honeymoon before Peter had to ship out. He was gone for three long years, serving mostly in the Pacific theater. During this time, Kristina continued living with her mother and working as a hairdresser. Her father, Andy, had died years before of a heart attack.

When Peter came home from the war, he got a job at AB Dick. Apparently, Peter was never a very talkative person before their marriage, but after the war, he was even less so. Still, he and Kristina seemed to have a relatively happy life. When she got pregnant with her first child, Edward (whom she supposedly named in honor of Eddy Howard), Kristina quit working to stay at home. A year later she had Mildred. Kristina enjoyed being a housewife, but she sometimes missed her clients. Once a month, she and Peter would host a card club. They also joined and became very active in the Elks. Her other hobbies were gardening and crossword puzzles. After only twelve years together, however, (not counting the war years), Peter died of esophageal cancer. Edward was eleven, and Mildred was just ten at the time.

After Peter’s death, Kristina had no choice but to go back to work. She found another job as a hairdresser, but it didn’t bring in enough money, so she found a night job at AB Dick. She went to Peter’s old foreman and begged him to find her something—anything. The foreman must have felt sorry for her and thus gave her a job in the shipping department. There were already too many shipping clerks, however, and the other women there resented her, believing that one of them was slated to get fired as a result. No one got fired, however, and they eventually came to like Kristina, especially since she often worked holidays for them and took the worst possible shifts.

Kristina was determined that Eddie and Mildred would not suffer for their father’s death and worked constantly to “give them everything.” She even saved enough to pay for Eddie to go to college. When they were finally raised and gone from the house, Kristina allowed herself to quit AB Dick and work only as a hair dresser, which she really enjoyed.

Despite having lots of friends and still being part of the ladies auxiliary of the Elks, however, Kristina was lonely, so her friends set her up on a blind date with a divorced man named David Abate, who worked as both a civil and an industrial engineer. David and Kristina hit it off right away, as did Kristina and David’s fifteen-year-old son, Kenneth. David eventually proposed to Kristina, and they married in 1971. David and Kristina have apparently had a very good life together, and Kristina and Kenneth became very close as well, something which Edward and Mildred are apparently upset about.

David says that he and Kristina tried over the years to include Eddie and Mildred into their life, but that the two of them remained aloof, despite living in the Chicago area. When they were together, they often argued, David says. During one such altercation, David relates, Edward and Mildred accused Kristina of never being there for them during their childhood years. Stunned, Kristina retorted that she had no choice but to work to support them. Even after that, however, Kristina refused to be angry with them. “She would always make excuses for them,” David says, and would deny that she was hurt by them or that there was any kind of problem with their relationship.

In 1987, Kristina was involved in a car accident as a backseat passenger. She was riding with some friends when they were rear-ended, and Kristina’s ankle snapped. She spent several weeks in the hospital recovering, but when she tried to go back to her job as a hair-dresser, she found the long hours on her feet too difficult. Thus she retired early, and she and David began traveling, mostly in the U.S., but once they even ventured to Mexico.

It has only been in the last couple of years that David has worriedly noticed Kristina becoming more and more forgetful. She lost interest in crosswords and in all of her old hobbies, one by one. David says she has gotten worse as time has gone on and has even started falling out of chairs for no apparent reason. He has tried his best to care for her at home, but he is constantly worried she will hurt herself. So it was with deep regret and sorrow that he decided, with Kenneth’s help, to put her in a nursing home. Apparently, he once promised Kristina that he would never put her in a home, so he is doubly wracked with guilt over her placement.

Kristina’s transition has been a bit rocky, as she is confused and has a hard time verbalizing her wants and needs. Often she says “I’m scared,” over and over and indeed looks frightened most of the time, despite the staff’s attempts at intervention and distraction. She recognizes David when he appears for his daily visit and is indeed less anxious when either he or Kenneth are present. David is also having a hard time with Kristina’s placement and expresses much anger toward Edward and Mildred. “She did everything for them!” he says. “She sacrificed the best years of her life, and this is how they repay her!” He is so angry at their lack of communication with Kristina over the years, that he is refusing to inform them that she is now in a nursing home. The support staff are trying to convince him that this is only serving to hurt Kristina, not them, but he refuses to listen.

When David or Kenneth are not around, Kristina seems the most comfortable when surrounded by other residents instead of alone in her room. She does not actively participate in activities unless someone helps her. Her favorite activity at the home so far seems to be “Big Band Hour,” but when asked about her wonderful encounter with Eddy Howard, she sadly doesn’t respond. When any big band songs are played, though, she is able to sing along and surprisingly, despite her memory loss in other areas, still knows all the words.

(Originally written: February 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Eddy Howard and His Big Band Played at Her Wedding! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.