Michelle Cox's Blog, page 18

March 18, 2021

“All I Know Is Horses”

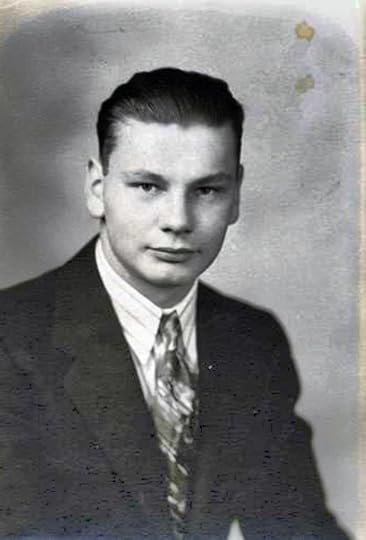

Leon Carter, Jr. was born on September 21, 1950 in El Dorado, Arkansas to Leon Carter, Sr. and Norma Jones. Leon, Sr. and Norma knew each other from little on. Not only did they go to school together, but their families were good friends and they were often together. Leon and Norma eventually fell in love and married. Leon worked in construction and did odd jobs, and Norma was a housewife. Shortly after their first child, Leon, Jr. was born, however, Norma abandoned them both and ran off to Chicago. She eventually married another man, Mario Sanchez, and had one daughter, Donna, with him. Later she married a third man, Reed Bryant.

Leon Carter, Jr. was born on September 21, 1950 in El Dorado, Arkansas to Leon Carter, Sr. and Norma Jones. Leon, Sr. and Norma knew each other from little on. Not only did they go to school together, but their families were good friends and they were often together. Leon and Norma eventually fell in love and married. Leon worked in construction and did odd jobs, and Norma was a housewife. Shortly after their first child, Leon, Jr. was born, however, Norma abandoned them both and ran off to Chicago. She eventually married another man, Mario Sanchez, and had one daughter, Donna, with him. Later she married a third man, Reed Bryant.

Leon Sr. did his best to raise “junior,” but when young Leon was about nine years old, his mother, Norma, reappeared in El Dorado, Arkansas and insisted on taking him back with her to Chicago. Norma put him in school here, and in the summers, he worked at the racetrack. After he finished tenth grade, he quit school and began working at the track full-time.

Leon says that he started at the bottom and worked his way up to being a groomsman. He began his career as a “hot walker,” which meant that he walked the hot horses after a race until they cooled down. He was a fast learner, he says, and quickly learned the best way to cool a horse, how much water to give them, etc., and how to care for them in general. He became an expert at horses, and his services were much sought after through the years.

Leon didn’t have much time for hobbies, but he did enjoy fishing, baseball, and playing cards or dominoes. He lived with his mother and his half-sister, Donna, until one day he met a young woman by the name of Patricia Woods, who was a co-worker of his mother’s. Leon and Patricia hit it off right away, and Leon soon moved in with her and her three daughters: Beverly, Cynthia and Deborah. Leon and Patricia never married, but they lived together for over fifteen years and had two sons together, Leon III and Robert.

Leon continued working at the track during the summers, but in the winters, he would head to New Orleans, where he worked at a track there. It turns out that in New Orleans, Leon had another girlfriend, Darlene Hayes, whom he lived with each winter for over twenty years.

Meanwhile, back in Chicago, Patricia was getting tired of Leon being gone half the year while she cared for five kids alone, and she decided to leave him. Leon claims that she was an alcoholic who was growing increasingly paranoid and suspicious of everything around her, including Leon and his double life in New Orleans.

Unfortunately, right at about the time when Patricia officially left him, Leon began experiencing some serious health problems. His legs were beginning to swell, and after going to the hospital, he was diagnosed with diabetes and kidney problems. He was in Chicago, so he couldn’t rely on Darlene, his New Orleans girlfriend/common-law wife. His mother, Norma, had died several years before, and his father had since moved to California to become a minister. Leon’s only choice seemed to be to go and live in Cabrini Green with his half-sister, Donna, his mother’s child with Mario Sanchez, and her six children, the oldest of whom was eighteen. Unbeknownst to Leon, however, Donna was a drug addict and soon stole all of his possessions and sold them for drug money, though she swore it wasn’t her.

Leon managed to put up with this living situation for a couple of years. Sadly, during that time, he got word that Patricia had died. He would have liked to go to the funeral, he says, but he didn’t know about it and blames his sons for not telling him. Both Leon III and Robert had apparently become estranged from their father over the years. Leon III had long since moved out of Patricia’s house and was living with his fiancé, and Robert was sharing an apartment with his half-sister, Cynthia, one of Patricia’s daughters.

Leon was very upset by Patricia’s death, but he soon had other things to worry about. Right at about that same time, Donna decided to jump ship as well and left Leon with her six children in the Cabrini Green apartment. Leon was still working on and off at the track, though he was limited in what he could do because of his health and did not get many hours. He tried to take care of his nieces and nephews as best he could, but the older ones especially did not appreciate their Uncle Leon’s involvement and blamed him for their mother, Donna’s, mysterious disappearance. Leon tried to teach them how to cook and fend for themselves, but they weren’t interested in listening to him. They often rebelled against him and, as his health grew worse and he became weaker, they sometimes even refused to give him food.

Leon’s health continued to decline, and he eventually had to have his left leg and his right foot amputated due to complications with his diabetes. He then went blind and had to rely entirely on whatever care or scraps his nephews or nieces would give him, the two youngest girls—Pamela, age twelve, and Jennie, age ten—being the most sympathetic to him.

Then out of the blue one day, Donna magically reappeared, apparently “strung-out,” says Leon, and threatened to go away again and take all of the children with her this time so that he would have to care for himself. As it turned out, however, as he ended up going to the hospital yet again and had to have extensive dialysis.

While in the hospital this time, Darlene, his girlfriend from New Orleans, appeared, saying that she wanted to be back in his life and take care of him. They soon fought, however, before he was even released from the hospital, and she declared their relationship over and went back to New Orleans. The staff at the hospital tried to reach his two sons, but they were not responsive. The hospital social worker then suggested that Leon be admitted to a nursing home, and, not having any other choice, he reluctantly agreed. He is hoping for prosthetic limbs, however, and a chance to get his own apartment.

While Leon says he is grateful to be somewhere getting care, he is dealing with a lot of conflicting emotions, especially anger. He says that his life’s motto has been to “grin and bear it,” but he admits to having a “hot temper,” which has affected many of his relationships in life. “I guess I screwed up my life,” he says. “All I really know is horses.”

Leon is depressed and sad that not one member of any of his various families have come to see him, nor has he gotten one card or phone call. He does not like to mix with the other residents because he sees himself as so much younger than them, but he is likewise bored and irritable. He is not accepting of the diabetic diet the staff have put him on, among other things, and is often verbally abusive to staff members because of it. He says he is biding his time until he can get his own place, sadly choosing to believe that Darlene might still come through for him.

(Originally written: May 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “All I Know Is Horses” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 11, 2021

A Brilliant Team—Married for 65 years!

Jan Marek was born on October 13, 1903 in Chicago to Zavis Marek and Valerie Reha. Zavis and Valerie were both immigrants from Czechoslovakia, but they met in Chicago and married here. Only three of their children lived to adulthoood: Jan, Victor and Teresa. Jan says that he often heard whisperings that his mother had experienced six miscarriages, but both of his parents refused to talk about it, even if asked directly. They also refused to talk about their life in Czechoslovakia.

Jan Marek was born on October 13, 1903 in Chicago to Zavis Marek and Valerie Reha. Zavis and Valerie were both immigrants from Czechoslovakia, but they met in Chicago and married here. Only three of their children lived to adulthoood: Jan, Victor and Teresa. Jan says that he often heard whisperings that his mother had experienced six miscarriages, but both of his parents refused to talk about it, even if asked directly. They also refused to talk about their life in Czechoslovakia.

Zavis owned a butcher shop, which the whole family helped to run, on Chicago’s northwest side. Jan and Victor worked there from a young age, and Jan had to learn to kill chickens, ducks and geese even as a little boy. Jan says it was “hard, hard work,” especially before they had refrigeration or automobiles. Neither Jan nor his brother Victor enjoyed working as butchers, and one day, they finally worked up the courage to tell Zavis that they had no desire to inherit the shop or to help keep it running once they were grown. Zavis was apparently very saddened by this news, but he agreed to let his sons pursue their own livelihood. When it was time for him to retire, he sold the shop instead of passing it down to them.

Once Jan graduated from eighth grade, he got a job delivering groceries, and his parents made him pay room and board from that point on. Jan worked hard, however, and managed to still save some money, even after having to pay his parents most of his salary. He continued to get various jobs, each one paying a little bit more, until, when he was twenty-one, he had saved enough money to put a third down on a hardware store.

Thus, young Jan became the proud owner of a hardware store, and he put his all into making it a success. He was a very social young man and knew how to treat customers from his many years working in his father’s butcher shop. He loved board games and sports and had a lot of friends. He was usually “the life of the party,” and could be found playing the piano and singing and dancing at get-togethers. It was at one such party at a friend’s that he was introduced to a young woman, Sonia Dusek, and the two immediately hit it off. They dated for a year and then got married and moved into the apartment above the hardware store.

Jan and Sonia were a brilliant team, apparently, both of them working very closely together to make the store a success. They worked hard all day and then would lock up the shop at closing time and go out dancing or catch a show. They both loved movies and saw almost every one that came out. They were always socializing with friends or family and often went to Jan’s parents to play cards.

The Mareks never had any children, however. Even though they were a very close couple, Jan says they never really discussed it. To his understanding, Sonia never really wanted any children, speculating that it might have had something to do with the fact that she was from a big family. “It was probably for the best,” Jan says now, though there is perhaps the tiniest hint of regret in his voice as he tells this part of his story.

When they were just short of fifty years old, Sonia one day declared that they should sell the hardware store and retire early. Jan was caught off guard by this sudden announcement, but after he had “time to think about it,” he decided that it wasn’t a bad idea. So they put the store up for sale, and it sold very quickly. The Mareks then bought a small bungalow on Pulaski Avenue to move into, having to give up their little apartment above the shop, and then began traveling. They also continued to go out dancing and to movies as well as to socialize extensively with friends and family, including Jan’s parents, whom they saw each week to play cards with.

Jan’s father, Zavis, died when he was eighty-six of esophageal cancer. He had been diagnosed with it two years before, but refused to have any kind of treatments. He died after a night of card-playing with Jan and Sonia. As he was going up to bed, he had a horrible coughing fit, and as Jan helped him to bed, “both of us knew he wasn’t going to make it through the night,” and they said their goodbyes. Jan’s mother, Valerie, then came to live with Jan and Sonia for the next fifteen years. She died at age one hundred in Jan’s arms.

Jan and Sonia continued to live in the bungalow on Pulaski until their own health began to fail. At that point, Sonia proposed that they move to the Momence Retirement Center in Momence, Illinois, where one of her sisters lived. Jan agreed to go, and they attempted to start a new life there. After only one year, however, Sonia passed away. She and Jan had been married for sixty-five years.

It was Sonia’s last wish to be buried by her parents in the Bohemian National Cemetery in Chicago, so Jan honored that with the help of the staff at the retirement community. Not wanting to return to Momence to live, however, without Sonia, he decided to move to a nursing home near the cemetery. He was able to do this mostly on his own, despite being ninety-one years old, though he had some help from his niece, Donna, who flew in from Seattle, Washington to help him get situated. She is his closest relative and is concerned for her Uncle Jan, but she is obviously not able to participate very much in his care. Jan remains very independent, however, and much of the admission process was handled by himself.

Jan is making a relatively smooth transition to nursing home life, though he is somewhat quiet and withdrawn. When asked, he says that he still misses Sonia, but he is “trying to make the best of it, the way she would have,” he says. He interacts well with other residents one-on-one, but seems to shy away from big group activities or events, saying his eyesight is too poor to enjoy much. He does still love music, though, and can often be heard singing to himself.

(Originally written: May 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post A Brilliant Team—Married for 65 years! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

March 4, 2021

A Bachelor Until Age 66!

Melvin Rosenberg was born on December 28, 1927 in Chicago to Lester Rosenberg and Rita Shain, who had also both been born in Chicago. Lester worked at the post office, and Rita cared for their three children: Audrey, Melvin and Wanda. Rita never worked outside the home except during the war years, when she took a job at a candy factory.

Melvin Rosenberg was born on December 28, 1927 in Chicago to Lester Rosenberg and Rita Shain, who had also both been born in Chicago. Lester worked at the post office, and Rita cared for their three children: Audrey, Melvin and Wanda. Rita never worked outside the home except during the war years, when she took a job at a candy factory.

Melvin graduated from grade school and went on to high school, where he took as many business classes as he could. When he graduated, he got a job in the office of a knitting mill. After the war broke out, he joined the navy, but he was eventually discharged due to stomach problems. Melvin had various jobs throughout his life and usually worked in shipping and receiving, as an order-filler, a stock clerk, or in maintenance.

In 1950, he decided to go on a “working vacation,” and traveled through Iowa, South Dakota and Wyoming for three months, picking up jobs as he went. It was a “stand-out time” in his life, he says, and talks about his travels frequently, even now. When the three month stint was over, he was tempted to extend it, but he was worried about his mother, so he made his way back home. On the day he returned to Chicago, he discovered that it was his younger sister, Wanda’s, wedding day!

Melvin also discovered that there was a letter waiting for him from the army, telling him to report for duty for the Korean War. He then had to try to explain to the draft board that he had already served in the army during WWII, but that he had been discharged due to poor health. He was eventually successful in clearing the matter up and then proceeded to get various jobs around the city of the type he had had before.

Melvin never married as a young man, he says, because he “never found the right woman.” He loved making things with his hands, going on trips, and playing poker and bingo. He also loved to cook, a skill he learned from his mother, whom he lived with on the northwest side until she died at age 93. Rita was still cooking up to the age of ninety, though, says Melvin, and over the years, she taught him how to cook many of her specialties. His older sister, Audrey, passed away when she was in her fifties from lung cancer, and Wanda had moved away shortly after her marriage. So when his mother died, Melvin was left on his own.

In 1983, he was able to get a union maintenance job at Armstrong and Blum tool makers, a job which he really enjoyed. “I made great money there,” Melvin says, but unfortunately he had a series of accidents on the job. After only six years there, he was forced to retire because all of his injuries prevented him from adequately doing the job. He was only sixty-two at the time. Shortly after that, there was a fire in his apartment building, and Melvin jumped from a 4th story window, breaking his ankle and his back in the process.

Melvin spent weeks in the hospital and was then transferred to a rehab center. From there, he really had nowhere to go, so he admitted himself to a nursing home, Clark Manor. He progressed so much over time, however, and became so independent that the staff at Clark Manor told him he would have to be discharged because he did not really need skilled nursing care. From there he went to a retirement-type of hotel, but it was very dirty, says Melvin, so he somehow checked himself back into Clark Manor. Again he was told he would have to leave, so he admitted himself to Alden, another nursing home.

Melvin was happy at Alden and became very attached to the woman in the room next to his, one Bertha Zimmer. As time passed, Melvin actually found himself in love with Bertha and asked her to marry him at age sixty-six. Bertha said yes, and they arranged for a rabbi to come and officiate. The staff helped Bertha’s daughter, Laura, throw a big party for them at the home. Melvin and Bertha were apparently happy together and enjoyed having Laura visit every day.

After about two years, however, Melvin grew dissatisfied with Alden and claimed that not only had two pairs of his slippers been stolen but that the staff had begun to hit him. Thus, Melvin and Bertha moved to another nursing home, Peterson Park, where they remained for another two years. Melvin enjoyed Peterson Park, but Bertha longed to go back to Alden because it was close to her daughter, Laura’s, house, which meant that Laura could easily visit daily. Peterson Park was farther, so Laura visited them less. Melvin refused to go back to Alden, so Bertha moved back on her own. After only two weeks at being back at Alden, however, Bertha passed away of a heart attack.

Bertha’s death hit Melvin very hard, and he at times still expresses anger at Bertha. “The doctor told her to lose weight and exercise, but she wouldn’t,” he says, frequently blaming her for her own demise. Shortly after her death, Melvin again sought to move to a different nursing home, again reporting that his slippers were stolen and that members of the staff had begun to hit him, the very same thing that had apparently happened back at Alden.

The staff at Peterson Park claim they were all completely shocked when Melvin expressed his desire to move and by his accusations of abuse. Before Bertha’s death, they claim that he always appeared happy and content. According to them, Melvin went into a depression after Bertha’s death, but they suspect that Melvin has been dealing with some form of mental illness since the fire in his apartment building, which has resulted in a paranoia that someone is trying to kill him. He uses the excuse of the stolen slippers and physical abuse from staff to cover up, they say, for his real fear, which is that someone is following him and wants to kill him.

Besides this apparent mental issue, Melvin is a very engaging, sociable man. He seems to be making a smooth transition to this new nursing home, his fourth, and participates in all activities offered. He is very helpful and is actively seeking out friends. He still misses Bertha, he says, and is sad that no one comes to visit. He understands that Wanda is too far away to visit and that she has her own health issues, but he feels hurt that Laura, Bertha’s daughter, never comes to see him anymore.

(Originally written: August 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post A Bachelor Until Age 66! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 25, 2021

Proud of working “in the clouds”

Glenn Brown was born on June 26, 1909 to Calvin Brown and Elaine Edwards, both of whom were immigrants from Australia. Calvin was a construction worker, and Elaine cared for their nine children: Timothy, Glenn, Charlotte, Theodore, Ida, Pearl, Leon, and Martin and Mary, who were twins. Glenn went to school until the eighth grade, but then quit to begin working construction alongside his father. Unfortunately, however, Calvin died young of a heart attack, and it fell on Glenn and Timothy to support the family.

Glenn Brown was born on June 26, 1909 to Calvin Brown and Elaine Edwards, both of whom were immigrants from Australia. Calvin was a construction worker, and Elaine cared for their nine children: Timothy, Glenn, Charlotte, Theodore, Ida, Pearl, Leon, and Martin and Mary, who were twins. Glenn went to school until the eighth grade, but then quit to begin working construction alongside his father. Unfortunately, however, Calvin died young of a heart attack, and it fell on Glenn and Timothy to support the family.

Glenn worked construction all his life and is proud of the fact that he worked on the “giants of the city,” including the Tribune Tower, the Chicago Board of Trade, The Prudential Building, and even the Hancock. He was not afraid of heights, he says, and enjoyed working “in the clouds.”

Glenn’s one hobby in life was playing baseball, and he joined quite a few local leagues in his youth. One year, the team he was on was sponsored by a tavern which had an adjoining liquor store. After each game, the team would frequent the tavern, with Glenn stopping at the liquor store afterwards before going home. The liquor store was managed by a young woman by the name of Wanda Ardelean, and Glenn began looking forward to seeing her each week, as “she was so easy to talk to.” Each time he went into the store, Glenn asked Wanda out on a date, but each time she said no. Finally, Glenn decided that he would ask her just one more time, and if she again said no, he would stop going to the liquor store altogether and just give up.

So, “on August 3, 1942,” he remembers clearly, he walked into the liquor store and again asked Wanda to go to the pictures with him. Expecting her to reject him, he was shocked and thrilled when she said yes! From that time on, the two began dating and eventually married. Not long after their wedding, however, the war broke out, and Glenn had to report for duty. He served for two and half years in Europe while Wanda continued to live with her parents and work at the liquor store.

When Glenn came back from the war, the couple got their own apartment on Belmont, and Glenn went back to working construction. Wanda continued at the liquor store, planning to quit as soon as she got pregnant, but, sadly, she never did. Glenn says he was disappointed not to have any children, especially as he came from such a big family, but “it couldn’t be helped,” he says. “It wasn’t meant to be.” He and Wanda instead became a favorite aunt and uncle to his many nieces and nephews. They also joined various bowling and card leagues over the years. He and Wanda never traveled much, he says, because “I was too busy working.” When he did have spare time, Glenn says that he “did a little gardening,” and he liked to read, especially the paper.

Glenn and Wanda lived in the apartment on Belmont their whole married life, both of them continuing to working the exact same jobs they had when they first met. Glenn worked until he was sixty-five, when he had to retire after he got “laid up” after having various minor surgeries. In 1988, Wanda passed away. After that, Glenn lived alone in the apartment on Belmont, but he relied heavily on his sisters, Ida and Pearl, and their families for help. His sister, Charlotte, had already passed away, and Mary became a nun early in life. All of his brothers were either dead or living in another state, so it fell on Ida and Pearl, or their children, to stop over to make sure Uncle Glenn was okay or to help him shop or clean.

This arrangement worked for several years until Glenn fell in his apartment and was taken by some neighbors to the hospital, where it was discovered that he was also suffering from pneumonia. After spending several weeks there, recovering, the discharge staff at the hospital did not feel he would be able to adequately care for himself at home, so nursing home placement was recommended. Glenn is upset at being admitted to a nursing home and blames the doctor for putting him here. His sisters have tried to explain that they cannot care for him, having their own health issues, and that it is safest for him in a staffed facility. Usually, Glen accepts this, but he sometimes forgets and then gets frustrated all over again. His family is extremely supportive of him, though, and someone visits at least once per week and often more.

Meanwhile, Glenn seems to be trying to make the best of his situation. “You have to work hard and keep busy,” is his motto for getting through hard times, “like now,” he says. He enjoys watching baseball on TV with other male residents and playing bingo, but at times he can be found clearing tables or straightening chairs in the dining room for “something to do.”

(Originally written: June 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Proud of working “in the clouds” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 18, 2021

The “Poison Powder”

Dariya Zelenko was born on September 1, 1914 in a small village in the Ukraine. Not much is known about her early life except that her maiden name was Dariya Kozel and that her parents were farmers. She apparently did not have any siblings and received little to no formal education at all, instead helping her parents on the farm as she grew up.

Dariya Zelenko was born on September 1, 1914 in a small village in the Ukraine. Not much is known about her early life except that her maiden name was Dariya Kozel and that her parents were farmers. She apparently did not have any siblings and received little to no formal education at all, instead helping her parents on the farm as she grew up.

When World War II broke out, the family was rounded up by the Germans and taken to a labor camp in Germany. At the camp, Dariya was somehow separated from her parents and tragically never saw them again. She was put to work on a remote farm and there met another prisoner, Kliment Sewick, with whom she eventually fell in love and “married,” though whether it was really official or not is unknown. Dariya had a baby, Simon, but shortly after his birth, Kliment was shot and killed by the Germans. Dariya was never sure why. Dariya grieved for Kliment, but later met another man on the farm, Martin Zelenko, and married him. Martin had befriended the German guards and was able to considerably lighten Dariya’s workload. He was also able to get them some extra food from time to time.

After the war was over, Martin immediately applied to come to America, and, finally, in 1951, he and Dariya and Simon arrived in Chicago looking for work. Martin found a job as a machine operator in a factory, and Dariya worked in a laundromat. Simon says that his mother had no hobbies besides gardening. She did not make any friends and did not ever really like to leave the house. She was very much a loner her whole life, Simon reports, and spent her time obsessively cleaning the house, sometimes scrubbing the floor three times a day. Simon believes this was the only thing his mother had that made her feel happy or worthwhile. Often she would say, “I never went to school, but I’m not stupid!” She was anxious, he says, unless she was working or constantly doing something and was perpetually trying to prove her worth through work.

Apparently, Dariya and Martin were never very close and argued frequently. Martin would often want her to go out with him, even just for a picnic on Sundays, but Dariya would always refuse, saying that she had too much work to do. Simon thinks that the reality was that she had an actual fear of leaving the house. She refused to even go to church, though she would get angry at Simon if he didn’t go every Sunday.

Finally, in 1974, Martin left Dariya and filed for a divorce. Simon had long since moved out and gotten married and says that the divorce didn’t really seem to faze his mother. He says that while his stepfather had his faults, he could see that as the years went on, Dariya became more and more unreasonable and withdrawn and that his stepfather had finally had enough of it.

After the divorce, Dariya remained alone, content to stay at home, cleaning and gardening. Things continued this way until 1991, when Dariya fell and broke a bone in her spine and had to go live with Simon. It was at this point that she began to rapidly decline mentally. Simon says that his mother then became extremely paranoid and began accusing him of trying to poison her. She would scream constantly at the top of her lungs, saying that Simon was putting poison in her food and throwing “poison powder” on her. She developed a persistent itch and subsequently took to hiding her clothes so that Simon wouldn’t throw poison powder on them.

Wanting to help and reassure her, Simon installed a lock on her bedroom door on the inside, so that she could lock herself in and feel secure. It didn’t work, however, as she then accused him of spraying the powder under the door. No matter what Simon did to try to alleviate his mother’s fears, it seemed to backfire.

Even when he was at work, Dariya thwarted him by going out into the yard and screaming at the neighbors, accusing them of also trying to poison her. She would shout that she knew that Simon was paying them to do it and would then throw mud on their windows. Dariya even chased her own grandson out of the house once because she was convinced he was part of the “plot” as well. This continued for three more years until Dariya fell and broke another bone, this time her leg. At that point, Simon decided it was a good opportunity to place her in a nursing home.

Simon feels guilty about putting his mother in a nursing home and stops by every night after work to check on her, but he is relieved as well, as it was just too difficult having her home. For her part, Dariya is not making a smooth transition. She seems not able to speak in a normal tone of voice and is instead always screeching and screaming at both the staff and the other residents, frequently shouting “shit!” as loud as she can. This disrupts the other residents, who in turn usually start shouting back at her or simply leave the current house activity to go back to their rooms.

The staff are trying to work with Dariya one-on-one, as an alternative to having her disrupt the other residents, but she appears very confused and unable to hold a normal conversation. Even though she can speak English, she will only answer questions asked of her in English with a response in Ukrainian or sometimes Polish. She seems unhappy most of the time and can usually be found trying to wheel herself up and down the hallways, wanting to keep moving, and becomes agitated if left alone in one spot.

(Originally written: July 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The “Poison Powder” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 11, 2021

“I’d Take Those Days Back in a Second”

Louis Dubois was born on March 6, 1913 in Chicago to Louis Dubois Sr. and Hilda Kempf. Both of Louis’s parents were also born in Chicago, though his father’s family had emigrated from France, and his mother’s family was an Irish-German mix. Louis Dubois Sr. was a star salesman for Armour Foods & Co., and the family lived on the south side near Comiskey Park. When Louis was just three years old, Hilda had another baby, William, but she died during childbirth. Louis isn’t sure, but he thinks his mother was probably only in her early twenties when she died. Louis Sr. began drinking heavily as a result, and Hilda’s mother had to step in to help raise Louis and Will. His father was able to “keep it together,” at work, but he became “a drunken idiot” at home each night. In that way, it was good that his grandmother frequently cared for them, but she was a “strict, hard woman,” Louis says.

Louis Dubois was born on March 6, 1913 in Chicago to Louis Dubois Sr. and Hilda Kempf. Both of Louis’s parents were also born in Chicago, though his father’s family had emigrated from France, and his mother’s family was an Irish-German mix. Louis Dubois Sr. was a star salesman for Armour Foods & Co., and the family lived on the south side near Comiskey Park. When Louis was just three years old, Hilda had another baby, William, but she died during childbirth. Louis isn’t sure, but he thinks his mother was probably only in her early twenties when she died. Louis Sr. began drinking heavily as a result, and Hilda’s mother had to step in to help raise Louis and Will. His father was able to “keep it together,” at work, but he became “a drunken idiot” at home each night. In that way, it was good that his grandmother frequently cared for them, but she was a “strict, hard woman,” Louis says.

Like so many others, the Dubois family was hit very hard during the Depression. Louis and Will would routinely walk along the railroad tracks and pick up stray bits of coal to help heat the house. They were terribly poor, Louis says, but he would “take back those days in a second.” Louis went to high school and eventually found work as a quality control clerk at Mills Novelty, a world leader in jukebox technology. He had a few hobbies, such as going to movies or watching sports, but mostly, he says, he just worked.

When he was twenty-eight, he met a young woman, Betty Rose, who was a waitress in a little diner he often frequented. Though she was only seventeen, he asked her out on a date to the movies, and they eventually started seeing more of each other. When Hilda turned eighteen, they got married. Unfortunately, Betty miscarried their first child and had to have a hysterectomy immediately following, so she and Louis never had any children. Betty continued waitressing over the years and sometimes cleaned offices at night. They weren’t particularly affectionate, Louis says, but he loved her, and he thought she loved him. “We made a go of it,” he says, and he still can’t understand why, after twenty years of marriage, Betty filed for divorce. “I guess she just went a little crazy.” When asked if the divorce was hard on him, he says, “No, not really. Well, a little bit.”

Louis describes himself as a loner and that he did not make many friends. His coworkers, he reports, always called him “negative.” His closest friend over the years was his brother, Will, who also divorced later in life and who also had no children. When Will died three years ago, Louis was left very much alone and took his death hard. “Our whole family died out,” he adds, sadly. “If you have friends today, you’re lucky.”

Louis has always been incredibly healthy, though he has been smoking for sixty years. He worked in a quality control position into his eighties and just recently had to quit his job at Cushing and Co., at age 83, after being diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. He explains that he went to the doctor for a routine check-up and was told he doesn’t have much longer to live. He does not seem to want to acknowledge or talk about his terminal illness. When asked if he is sad or upset, his response is “No, not really. Well, a little bit. I wish I was at work.” After a short stay in the hospital, he was admitted to a nursing home, which he helped to choose.

Louis is making a relatively smooth transition, but he does not seem to be bothered by much. He appears withdrawn and depressed most of the time despite his comments otherwise. “I’ve had a boring life,” he says. “All I did was go to work, come home and watch TV and then go to bed.”

His favorite thing to do seems to be talking about “the good ole days,” as he calls them. He is thoroughly disgusted with modern society and longs for the days when people knew their neighbors and smiled at people on the streets. “No one locked their doors back then,” he says. “In the summer time, we all slept on the beach for the breeze, and no one murdered you.”

He seems aware of his negativity, saying “no one wants to talk to me because I’m depressing,” but likewise doesn’t seem to be able to control it. He says he wants to die and “get it over with.” Staff at the home are attempting to connect him with other residents who might also like to talk or to watch sports on TV with him.

(Originally written: June 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “I’d Take Those Days Back in a Second” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

February 4, 2021

“The Tragedy of My Sister’s Life”

Anna Fox was born on April 12, 1918 in Russia to Aron and Riva Kaplan. Aron was a shoemaker, and Riva cared for their five children: Anna, Lev, Isak, Boris, and Klara. All but Klara survived childhood. Like many people of that era, Aron and Riva were desperate to leave Russia, but they could not obtain visas to the United States. Instead, they opted to go to Cuba, hoping that they would eventually find a way into America.

Anna Fox was born on April 12, 1918 in Russia to Aron and Riva Kaplan. Aron was a shoemaker, and Riva cared for their five children: Anna, Lev, Isak, Boris, and Klara. All but Klara survived childhood. Like many people of that era, Aron and Riva were desperate to leave Russia, but they could not obtain visas to the United States. Instead, they opted to go to Cuba, hoping that they would eventually find a way into America.

Anna was only about four or five when the Kaplans arrived in Cuba. She attended school and learned Spanish very quickly. She even graduated from high school, after which she found various jobs around Havana, which is where the Kaplans had settled.

In 1944, when she was twenty-six years old, Anna was finally granted permission to go to America, though the exact details of how that came about have been lost over the years. Apparently, it had something to do with Aron having a brother and a sister-in-law living in Chicago, and Anna was allowed to go and live with them. She quickly found a job in a factory that made envelopes and tried to learn English. Not long after, her brother, Lev, arrived and after finding a job himself, he and Anna were able to get their own little apartment, working and saving to eventually bring the rest of the family over.

Anna was apparently a quiet girl who had few hobbies beyond knitting and crocheting and went on dates rarely. So when some friends from work introduced her to a handsome soldier just back from the war, Anna was quickly smitten. Bert Fox swept Anna off her feet and asked her to marry him not long after they started dating. He had a good job at Allied Appliance in the shipping department, and Anna said yes to him, despite the fact that they did not know each other all that well.

According to Anna’s brother, Lev, she and Bert seemed to have a good relationship for the first ten years of their marriage. No children came along, apparently because of Bert’s many war wounds, though the war was something Bert refused to talk about. He was not overly liked by Anna’s family, but they tolerated him. Anna and Bert mostly kept to themselves and rarely attended family get-togethers. Lev often complained of this to Anna and blamed Bert for keeping her from them, but Anna would never criticize Bert or attempt to change his mind.

One day out of the blue, however, Lev received a telephone call from Anna, who was crying and upset. Anna told him that Bert had somehow “snapped” and caused a big scene at the envelope factory, where she still worked. Bert had apparently stalked in and picked a fight with her boss, demanding that he fire her, though he could not name a reason. Bert became increasingly belligerent and started punching people, so the police were called. Anna, despite being a good and loyal employee for years, was fired on the spot. Anna’s boss did not press charges, however, so the police allowed Bert and Anna to go home. Bert had seemed to calm down on the way home, but once they got back inside their apartment, he “snapped” again and began to beat her. This began a sad, brutal pattern that happened over and over as the years went on, with Anna even having to be hospitalized on several occasions.

Desperate to help his sister, Lev attempted various times to go to the police himself, but, though they sympathized with him, he was told he had no legal right to interfere. Because Bert sometimes “snapped” in public, however, causing property damage or beating other people up, he was actually arrested several times and eventually taken to the psychiatric ward of various hospitals—one time being held for over six months. These episodes in which Bert was hospitalized were a blessed relief for Anna, Lev says, but Bert would always somehow be released and then the cycle would start all over again.

Lev despairs at what he calls “the tragedy of my sister’s life” and says she is definitely suffering from “battered wife syndrome.” Repeatedly over the years, he and his wife, Glenda, tried to get Anna to leave Bert, but each time she refused. Lev is of the opinion that the years of abuse have gradually taken their toll and that Anna is now beginning to show signs of dementia, becoming more and more confused and forgetful in the last five years. This prompted Lev to begin proceedings to obtain guardianship for his sister, which he was recently awarded. Therefore, when Anna was again hospitalized about a month ago after yet another beating from Bert, Lev was able to arrange for her to be discharged directly to a nursing home.

Bert, meanwhile, has no knowledge of Anna’s whereabouts and still believes her to be in the hospital. The staff have been instructed never to contact him. Lev is relieved that his sister is finally in a safe place and visits her daily, but Anna sometimes does not even recognize him. When she does, she is angry at him for bringing her to this “hospital” and wants to go home, accusing him of wanting to steal her money. Likewise, she forgets that Lev’s children are grown and married and is instead constantly reminding him to go pick them up from school.

Anna is extremely confused and usually speaks only in Spanish, even to the staff. When the staff remind her to speak in English, her reply is, “Sure. Sure, honey,” but then she proceeds to speak in Spanish all the same. She has told Lev that she believes the staff are “against me” and therefore speaks in Spanish so that “they won’t hear me.”

Anna spends her days roaming the halls, muttering to herself in Spanish. When redirected to a room with other residents, she immediately begins to find ways to “help,” such as by removing tray tables or walkers in an attempt to “tidy up,” which inadvertently puts other residents in danger of falling. Staff are attempting to give her meaningful tasks to do, but she frequently wanders away from the room, asking to go home.

(Originally written March 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post “The Tragedy of My Sister’s Life” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

January 28, 2021

A Sicilian Immigrant With a Passion For Sports

Umberto Sartori was born on February 23, 1916 in Biscari, Sicily to Stefano and Lucia Sartori. Stefano and Lucia married very young and had six children, but when Lucia was just thirty-three, she caught pneumonia and died. Grief-stricken, Stefano decided to pack up the six children and move to America to start his life over. The Sartoris settled in Chicago, and Stefano took any job that came along until he eventually became an importer/exporter of cheese and olive oil. He died at age sixty-two when he was mysteriously hit by a car.

Umberto Sartori was born on February 23, 1916 in Biscari, Sicily to Stefano and Lucia Sartori. Stefano and Lucia married very young and had six children, but when Lucia was just thirty-three, she caught pneumonia and died. Grief-stricken, Stefano decided to pack up the six children and move to America to start his life over. The Sartoris settled in Chicago, and Stefano took any job that came along until he eventually became an importer/exporter of cheese and olive oil. He died at age sixty-two when he was mysteriously hit by a car.

Umberto attended high school and college and even went on to get his masters in physical education from George Williams College. His first teaching job was at the University of Illinois, Chicago when it was still located at Navy Pier. When the university outgrew Navy Pier and a new facility was built at Harrison and Halsted, Umberto moved with them. While there, he continued to teach classes and also became the director of the intramural sports program, his favorites being basketball and softball.

In his free time, Umberto joined a bowling league, which is where he met his future wife, Estelle. Estelle was also on a team with her friend, Maria, and her sister, Ann, and Ann’s husband, Jim. Umberto happened to know Ann from the university and came to watch their team perform. Ann introduced Umberto to her sister, Estelle, and the two hit it off right away. They married and had two children, Tom and Nancy. “He was a good father,” Tom says. “He got us into every sport under the sun and went to all of our games religiously. He had a real passion for sports. His dream as a kid was to make the major leagues in baseball, but it didn’t happen, so he decided to teach and coach instead.”

When Estelle died suddenly in 1973 of a heart attack, Umberto was grief stricken. He threw himself even more into his work and became almost a recluse, as Tom and Nancy had already moved out of the house. So when two years after Estelle died, Umberto began dating again, Tom and Nancy were delighted. They were happy, they say, that he seemed to be moving past the grief of their mother’s death and was interested in seeking out the company of other women. But they were a little shocked when he began to seriously date a woman by the name of Patty McConnell, who was thirty-two years his junior. Umberto met Patty at the University of Illinois, where he still taught and where Patty was also working on her masters in physical education. In 1975, when Umberto was fifty-nine and Patty was twenty-seven, they married.

After a few years together, Patty was offered a job in North Carolina, so she and Umberto and Patty’s daughter from a previous marriage, Jennifer, moved to Charlotte. After a few years there, they moved again to New Jersey for a new job for Patty. At this point, Umberto was retired. In all, they were together for about twelve years when Umberto started to show serious signs of aging and was eventually diagnosed with Parkinson’s. In the end, Patty could not deal with Umberto’s disease, and the two divorced. Patty and Jennifer remained in New Jersey, and Umberto returned to North Carolina. He lived there on his own for about four or five years until his Parkinson’s had progressed to the point that he could no longer care for himself.

Defeated and depressed, he returned to Chicago and moved in with his daughter, Nancy, who cared for him with the help of Tom and his wife, Leyla, who lived in the apartment below. Nancy and Tom tried valiantly for a year to care for their father, but it began to be too much. Whenever they would bring up the topic of a nursing home, however, Umberto became very angry and was completely resistant to the idea. Nancy and Tom, struck with horrible guilt, sought out the help of a therapist to deal with their many feelings about Umberto and what to do. Eventually, the arrived at the decision to place Umberto in a nursing home for everyone’s well-being.

As expected, then, Umberto is not making the best transition to his new environment and is particularly frustrated by his limited physical and verbal abilities. He struggles to walk without assistance and has a hard time expressing himself now that his disease is so advanced. He is usually polite to the staff, but he has a lot of anger toward Nancy and Tom. He says that he feels abandoned and depressed, though he admits he cannot care for himself. He has yet to make any friends at the home and focuses, almost obsessively, on the physical exercise programs offered, though he is not able to fully participate. Nancy and Tom are heartbroken about their father’s condition but continue to try to support him and visit multiple times a week, despite Umberto’s anger and sometimes indifference toward them.

(Originally written: November 1993)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post A Sicilian Immigrant With a Passion For Sports appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

January 21, 2021

“He Could Make Anyone Laugh”

Brian Cullen was born on March 7, 1927 in Ireland to James and Moreen Cullen. He was the second child of five, with two brothers and two sisters. His father, James, worked in construction and on farms, and his mother, Moreen, was a housewife. Brian went to grade school and then went on to a trade school to learn to be a millwright. He eventually got a job in this field and worked in it steadily over the years.

Brian was the favorite amongst all his brothers and sisters and was always telling jokes and funny stories. He had various girlfriends, but he never married, which everyone thought odd, since he was so popular. It was just after he turned thirty that he shocked his family by telling them he was going to try his luck in America. They all thought this was another of his jokes and at first did not take him seriously. They were stunned and utterly saddened, then, when they finally realized that he was in earnest. He told them that there was no future for him—or for any of them—in Ireland and that they should come with him to America. None of them wanted to leave, however, so they tearfully said goodbye to each other. Brian eventually did return, much later in life, but by then his parents and one brother had already passed away.

So in 1957, he made the journey alone to America and uncovered an aunt, Bridget Moran, who was living in Chicago. He joined a union and got a job fairly quickly, again working as a millwright and eventually found an apartment on the west side. Every Sunday, however, he would go to his aunt’s on the south side for Sunday dinner. It just so happened that next door to his aunt lived a young couple, Tom and Eva, who also entertained on Sundays. Usually, it was Eva’s friend, Patsy Reid, that would come over. Thus on many a Sunday, Brian and Patsy would see each other and would get to talking. Sometimes, Brian would even drive Patsy home. They began dating and were married in 1966 when Brian was 39 years old. They moved to an apartment on the north side and eventually had one daughter, Connie.

Patsy says that Brian was a laid-back man in many ways with a wonderful sense of humor. “He could make anyone laugh,” she says, “but he liked to be in control.” Patsy says that Brian was very old-fashioned in many ways, very Victorian in his view of certain things, and was very stubborn. He saw himself as the man of the family, the provider, and thus it was his way or no way. He would not allow Patsy or Connie to get their ears pierced or to drive a car, for example, even though Connie took Drivers Ed. in school. “It wasn’t that he was mean,” Patsy says, “it’s just that he thought he should be responsible for everything. If Connie or I wanted to go somewhere, he thought it was his duty to drive us there.”

Brian was a devout Catholic who prayed the daily devotions and went to Mass each morning. He was a huge sports fan and loved basketball and baseball, but his favorite was hockey. He spent a lot of time doing yard work and always put in a big garden each year. As he got older, however, he began to suffer from arthritis in his hip, and only then would he consent to have Patsy and Connie help in the garden, under his direction, of course.

When he retired, he and Patsy went on several trips to Ireland so that he could introduce Patsy to all the relatives and to see his home town. They also ventured to Yugoslavia, England and France. He was a heavy smoker, Patsy says, until the late 1970’s when he quit cold turkey after he accidentally lit two cigarettes at once. For some reason, that was a signal to himself to stop.

Patsy says that besides his arthritis, Brian was always in great health, which is why his recent stroke came as such a surprise. He had gone to the doctor for his annual checkup and had gotten a clean bill of health. Two days later he had a massive stroke and was hospitalized for nearly a month before being discharged to a nursing home, as Patsy cannot possibly care for him alone at home. Connie is likewise not able to help, as she now lives downstate with her husband and children. She has come up to visit once since Brian’s admission to the nursing home, but she had to return after only a few days due to her job and having her own family to care for.

Brian’s transition to the home has been relatively smooth, as he does not seem completely aware of where he is. He can answer some questions from time to time, but he is mostly unresponsive. When someone from the staff attempts to talk with him, he will look at them and take their hands, but seems unable to always answer. It is Patsy who is having a harder time dealing with her husband’s condition and rapid decline. She keeps saying over and over, “but the doctor said he was healthy. He’s not supposed to be this way.”

(Originally written: February 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post “He Could Make Anyone Laugh” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

January 14, 2021

The Odd Life of Joseph Hertz

Joseph Hertz was born on May 3, 1916 in Washington, D.C. to Victor Hertz and Lena Aerni. Victor was of German descent and worked as the head accountant in a large firm in Washington. Lena was of Swiss descent and cared for their two children, Joseph and Louisa, who were five years apart.

Joseph Hertz was born on May 3, 1916 in Washington, D.C. to Victor Hertz and Lena Aerni. Victor was of German descent and worked as the head accountant in a large firm in Washington. Lena was of Swiss descent and cared for their two children, Joseph and Louisa, who were five years apart.

When Joseph was very small, Victor was transferred to Columbus, Ohio. Joseph says he has only one memory from their time in Columbus. He remembers going to a park with his father and seeing some swans swimming on a small pond there. Joseph desperately wanted to pet them, so he wandered into the pond, not knowing how to swim. Miraculously, his father saw him just as he was going under and jumped into the pond to save him.

After only a few years in Ohio, Victor was again transferred, this time to La Grange, Illinois, where Joseph attended elementary and high school. His father went golfing every Saturday at the country club, and when he was old enough, Joseph was allowed to go with him. Joseph was a hard worker and besides keeping his grades up, had various odd jobs, such as mowing lawns and weeding gardens. He eventually got a “real job” delivering groceries. Most of his time, however, was taken up in helping his “no good sister, Louisa.”

Louisa, five years Joseph’s senior, married young and had a baby almost immediately. Louisa, it seems, was not the maternal type and frequently forced Joseph to watch the baby, Carolyn—or Carrie, as she was called—while she and her husband went out. Joseph said he loved Carrie and didn’t mind caring for her, but it was hard for him to balance everything. His dream was to go to Notre Dame and play football.

Just a few weeks shy of his high school graduation, however, a terrible accident occurred. The school held a dance, which Joseph attended with a girl he had been set up with. Afterwards, he politely walked her home, but as he was turning the corner to return to his own house, a car jumped the curb and hit Joseph nearly head on. Joseph spent weeks in the hospital with a brain injury, and for awhile, it wasn’t clear whether he would even live. He eventually came out of the coma he was in and began to mend, but his dreams of graduating from high school and going on to college were crushed.

His parents helped Joseph at first, but after several years, they forced him to move out on his own, though it is not clear why. His father did help him to get a job in a laundromat, but when Joseph didn’t show up for work one day and didn’t call, he was fired. Joseph tried to explain to the manager that he had fainted at home and obviously couldn’t call, but the manager didn’t believe him. He had a whole string of jobs after that, but eventually the same thing always happened. He would either pass out at home or on the job and would then be fired.

At one point he managed to get a job at Wallis Press, first on the cutting machine and then on the folding machine. He was very nervous that he might pass out while operating such heavy machinery, but he tried his best. His foreman, Bill, took a liking to Joseph and felt sorry for his condition. Often he covered for him, even punching him on and off the clock sometimes if he couldn’t make it into work. One day, however, Joseph happened to pass out in front of the owner, who promptly insisted that Joseph go see a doctor. Not surprisingly, the doctor diagnosed him as “unfit to work” and said he would inform the foreman and the owner that Joseph would not be coming back and explain why. Depressed by the news, Joseph couldn’t bear to go back, even to say goodbye.

Several years later, while walking down a street in Chicago, Joseph felt a shove from behind and turned to see his old foreman, Bill, who was clearly upset with him. He accused Joseph of walking off the job after he had done so much for him. Joseph hurriedly explained that the doctor he had been forced to go to had diagnosed him as “unfit to work” and that he was supposed to have sent some kind of a report to the factory verifying that. The foreman claimed that they had never received a phone call or a letter from this doctor, which had led them all, at the time, to believe that Joseph had merely quit. Joseph apologized for the misunderstanding, almost crying, and Bill apparently felt so bad for him that he offered Joseph a “light duty” job in the mail room if he wanted to come back. Joseph thanked him for the offer, but ultimately didn’t feel like he could accept it.

After that, Joseph says that he hit an all-time low. He claims that he was married twice, both times to nurses, but that they both died. He met his first wife, Agatha, while he was convalescing in the hospital after being hit by the car. Several years later, they finally married, though she died shortly after from cancer. He somehow met another nurse, Marion, who also died, though it is not known of what. After Marian died, Joseph was alone in the world. Both of his parents had died young, and Louisa and her family had since moved to Kansas and did not maintain contact with him.

Without a job or any hopes of ever being able to hold one down, Joseph became homeless and eventually began sleeping on park benches. One night, after some cops came by and tried to get him to move on, a strange man approached him and asked him if he needed a place to stay. Joseph said yes, but told the man that he had no money. The man asked him if he could stand living in the park for just one more night until he could get a place ready for him. Joseph said yes and the next day showed up at the man’s apartment, as instructed. Joseph says that there were many homosexual men living in the building, so he decided to stay with them for only a couple of nights. Whether through their help or on his own, he was eventually able to get a job at a restaurant and then at a newsstand.

Joseph seemed to be able to handle working at the newsstand pretty well. One customer became a sort of friend and eventually told Joseph that he knew a woman he would like to introduce him to if he was agreeable. Joseph said yes and, with his friend, went to meet the woman, Betty Lindh, who was living with her aunt, Thelma Kloburcher. Betty had been married before, Joseph learned, but her husband had routinely beat her, so she eventually divorced him. She worked at the Harvard Insurance Company, but, like Joseph, had been in a car accident, which left her “a cripple,” and she used a walker to get around.

Joseph and Betty took an instant liking to each other and married quickly, each one willing to overlook the other’s disability. Joseph moved in with Betty and Thelma, but it soon became evident that this arrangement was not going to work out. Thelma became extremely jealous of any attention the Joseph and Betty gave each other, culminating in Thelma one day breaking a plate over Betty’s head.

After that, Joseph and Betty took a room at a boarding house at Clybourn and Fullerton for $16 a week, and later moved across the street to a one-bedroom apartment for $18 a week. According to Joseph, he and Betty had a very tumultuous sort of relationship. Joseph says that they loved each other very much, but that they had a lot of problems, the biggest one being Betty’s alcoholism. Joseph claims that she often did strange, unpredictable things, like waiting for him with a knife one night when he came home from work. She was furious with him for something, and Joseph thought she was waving the knife at him to make a point of scaring him. He was stunned, then, when she actually lunged for him and stabbed him in the side. He did not go to the hospital, however, not wanting to report it. Instead, he bandaged it himself and waited for it to heal. He admits, though, that he was equally violent at times, and claims to have attempted to strangle her one night. Having violent, emotional battles, often involving some sort of physical abuse, followed by a speedy, dramatic make-up, seemed to be a recurring pattern in their relationship.

In 1987, Betty’s health began to go downhill, so much so that it became apparent that she needed to be admitted to a nursing home, as Joseph could no longer take care of her. Joseph couldn’t stand the idea of being parted from her, however, so he checked himself into the same nursing home. After only six months, however, Betty passed away, leaving a grieving Joseph behind. After her death, Joseph began to hate the facility and wanted to transfer to a different home. He appealed to the public guardian’s office, saying that he was a victim of elder abuse. A guardian was appointed, and though no proof of abuse was ever produced, the guardian was able to find a new placement for Joseph.

Joseph is currently enjoying his new surroundings, though he says he misses Betty terribly. He also misses some of the staff at the other nursing home whom he had gotten used to and who had befriended him. Still, he says, “it’s not all bad.” His favorite thing to do is to watch baseball on T.V. and particularly enjoys it if a group of other residents sit near him.

(Originally written February 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also avail able AUDIO !

The post The Odd Life of Joseph Hertz appeared first on Michelle Cox.