Michelle Cox's Blog, page 20

September 17, 2020

She Never Really Stopped Loving Him

Grace Phillips was born on October 3, 1922 in Alder Point, Nova Scotia to Warren McAndrews and Mary Jane Wilson, both of whom were Scottish Canadians. Warren was a coal miner, and Mary Jane cared for their ten children: Margaret, Grace, Leon, Calvin, Rosemary, Dale, Katherine, William, Mattie and Lillie. Lillie was actually the daughter of Mary Jane’s best friend who had died during childbirth. Lillie’s father was overwhelmed and distraught and had no use for the baby that had somehow lived despite the botched birth, so Mary Jane took her and raised her as their own daughter.

Grace Phillips was born on October 3, 1922 in Alder Point, Nova Scotia to Warren McAndrews and Mary Jane Wilson, both of whom were Scottish Canadians. Warren was a coal miner, and Mary Jane cared for their ten children: Margaret, Grace, Leon, Calvin, Rosemary, Dale, Katherine, William, Mattie and Lillie. Lillie was actually the daughter of Mary Jane’s best friend who had died during childbirth. Lillie’s father was overwhelmed and distraught and had no use for the baby that had somehow lived despite the botched birth, so Mary Jane took her and raised her as their own daughter.

When Grace was about twelve or thirteen, the McAndrews decided to move to Chicago in hopes of a better life. Warren, desperate to get away from the mines, found “a good job” in the city as a carpenter. Grace only completed seventh grade and then stayed home to help her mother with their large family. In her teens, she got a job at a factory that made decorative braiding, a skill Grace became quite good at. It was one of the things, actually, that attracted her future husband, Gordon Phillips, to her. When he first met her, he noticed that even though the clothes she wore were simple and not expensive, she made them look elegant by adding braiding.

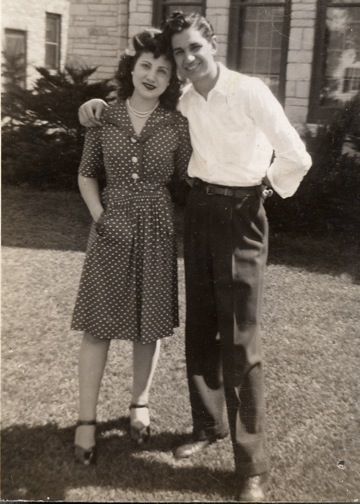

Grace and her sister, Rosemary, had the same set of friends and often socialized in the big dance halls around Chicago. It was at one such place, the Merry Gardens, that Grace was introduced to a mutual friend, Gordon Phillips. Gordon and Grace started dating and fell in love, but when the war broke out, Gordon immediately joined up. They decided to get married before he shipped out, so Grace bravely traveled alone to North Carolina where Gordon was stationed in order to get married, as he was not allowed to leave the base. Shortly after the wedding, Gordon was indeed shipped out to Europe, so Grace returned home to Chicago to live with her parents and to wait for Gordon to come back. She got a job in the meantime at a factory that made gold rings.

Unfortunately, the war did not go well for Gordon. He was captured by the Germans and spent eight months as a prisoner of war. When he finally came home, he was only 110 pounds. He got a job right away, however, in a tool and die factory, and Grace quit her job to be a housewife and then a mother. Together, she and Gordon had three children: Donna, Carol and Steven. They began their married life in a small apartment on the north side and moved from place to place until they settled in an apartment on Diversey, where they remained together until 1970.

Grace and Gordon’s marriage, however, was not a happy one. “He was never the same” after the war, Grace often said. “He wasn’t the man I married.” Grace tried hard to make it work, but Gordon began drinking more and more until she could no longer take it. Gordon moved out and eventually remarried, while Grace remained in the apartment with Steven, the only child still at home. Grace got a job as a purchasing clerk for the Society for Visual Education in Chicago and managed to support herself and Steven over the years.

Grace’s daughter, Donna, remembers her mother as being very submissive to Gordon, who suffered from severe mood swings, among other things. “But when she divorced him,” Rosemary says, her mother became “much more independent.” She went out more and became more social. She had always enjoyed reading, embroidering and crocheting, but she now took up walking, too, sometimes spending her entire day off simply walking through the city. Once Steven got married and moved away, she likewise got more involved in her church, St. Bartholomew, and volunteered many hours to the St. Vincent De Paul society.

In 1990, Grace decided to move to a new apartment, but after only two years in the new place, she was robbed twice and mugged once on the street. She decided at that point to retire from her job and move to a better apartment on Patterson. Grace continued with her hobbies and volunteering, though, until February of 1994, when she discovered that Gordon had died. He had had a quadruple bypass the year before and had been recently diagnosed with prostate cancer. While in the hospital having surgery to remove the cancer, there was apparently a mistake made that caused Gordon his life. His heart had begun to beat irregularly, so he was given a medication to slow it down a bit. Tragically, however, the nurse on duty accidentally administered 10x’s the amount prescribed, which stopped his heart completely, and he died.

Though Grace and Gordon had lived for years and years apart with little or no contact between them, Grace was very affected by Gordon’s death and went into a depression after he died. Donna believes that her mother never really stopped loving her father. According to Donna, Grace never once spoke negatively of their father, despite all that had gone on between the two of them. It is perhaps not surprising, then, that just two months after Gordon’s death, Grace suffered a stroke, which left her right side paralyzed. She spent five weeks in the hospital recovering. When it was time for her to be discharged, her family suggested giving a nursing home a try. Grace agreed to this but believes her stay at the home to be temporary, though her daughter, Donna, confirms that she and the rest of the family feel it is a permanent move, as it is impossible for her to care for herself now.

Grace seems in relatively good spirits and has a great sense of humor, but she is very frustrated by her inability to effectively communicate because of the stroke. Her speech is severely limited. She can get simple things across, but relies on her daughters to give more lengthy explanations to the staff whenever they come in to visit, which is somewhat problematic for all concerned and for obvious reasons. Grace has been successful, however, in communicating to the staff that she wants to be up and about in her wheelchair and not lying in bed. Though she cannot really talk to the other residents, she prefers to be sitting among them and is eager to participate in activities if a staff member or a volunteer can sit and help her.

(Originally written May 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post She Never Really Stopped Loving Him appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 27, 2020

A Wonderful Father and an All-Round Outdoors Man

Samuel Werner was born on April 25, 1920 in St. Louis, Missouri to Arne Werner and Kathleen Murphy. Kathleen was born in Ireland and was just a baby when her family immigrated to Texas. When she was only three, the family moved again to St. Louis. Similarly, Arne had been born in Germany, and when he was a small child, his family immigrated to St. Louis as well. Arne and his brothers grew up in St. Louis and ironically ended up fighting in WWI on the American side. Together, Kathleen and Arne had ten children. Only one, James, died in childhood at eight months.

Samuel Werner was born on April 25, 1920 in St. Louis, Missouri to Arne Werner and Kathleen Murphy. Kathleen was born in Ireland and was just a baby when her family immigrated to Texas. When she was only three, the family moved again to St. Louis. Similarly, Arne had been born in Germany, and when he was a small child, his family immigrated to St. Louis as well. Arne and his brothers grew up in St. Louis and ironically ended up fighting in WWI on the American side. Together, Kathleen and Arne had ten children. Only one, James, died in childhood at eight months.

When Samuel was just two years old, the family moved to Chicago where Arne was able to find work as a sheet metal worker. Sam attended grade school and went to high school for a little while before he quit to attend a technical school to learn to be a sheet metal worker like his father. He was soon apprenticed, and when he completed his apprenticeship, he and Arne went into business together, owning their own shop for 34 years.

Sam’s mother, Kathleen, was never in great health and continued to have miscarriages. She was over 300 pounds and had what was called “dropsy.” She died when she was just forty-seven. It was Sam that discovered her. He had just come home from buying his sisters their Easter dresses and found his mother dead in her bed. Arne also died young, at age fifty-eight, of a ruptured spleen.

Sam took over the sheet metal shop and eventually married one of his sister’s friends, a girl by the name of Minnie Kunkle. He and Minnie had six children: Peggy, Janet, Doris, Gary, Roger and Arnold. Sam was a very outgoing man who loved music and singing and could play the harmonica, the piano and the organ, all of which he taught himself. His favorite forms of music were Irish ballads and country music because, he once said, the lyrics of both are so sad. For a time he even sang in the choir at his church, St. Timothy’s Lutheran, which was very near their house on Armitage. He was a very outdoorsy sort of man, as well, and also enjoyed hunting, fishing, camping, horseshoes, Ping-Pong, blackjack and sports of any kind. He had “a real zest for life” and was interested in many different things.

For some unstated reason, his marriage to Minnie did not work out, and they divorced in 1971. That same year, Sam decided to remodel a building he owned on Belden and hired a woman by the name of Maria Pasternak to come in and varnish the stairwell. Sam had not met her before, as she had been recommended by someone at work. He was waiting in the foyer of the building to let her in to start the work, and when he saw her, “something just clicked” between the two of them, Maria says. She was a divorced woman, twenty years his junior, with three kids. “It was not an ideal situation by any stretch,” says Maria, but they began dating anyway and married the following year.

Sam helped raise Maria’s three kids: Earl, Patsy and Roy, and became fiercely attached to them, almost more so than to his first six children with Minnie, who had all gone to live with her. He and Maria had a very close relationship and appear to love each other very much, even now. “He was a wonderful father,” Maria says. “He never, ever lost his temper” and seemed to have infinite patience.

Sam continued working at his sheet metal shop until the IRS caught up with him in 1985, and he lost it due to back taxes. It was sold to a new owner, who kept Sam on as an employee. Sam continued working in the shop for four more years until he quit because his arthritis was getting so bad. Then, in early 1995, he also lost his building on Belden due to back taxes and consequently went slipped into a deep depression.

Maria believes the stress of these events caused Sam to have a heart attack, from which he spent many weeks in the hospital recoverin. He was just about to be discharged when his doctor decided to do one more test. Maria believes that the staff somehow botched the test because during it, Sam turned gray and stopped breathing. The staff immediately tried to counteract whatever they had done, says Maria, and whisked him off and put him on life support.

Sam spent five weeks in a coma, during which time Maria rarely left his side—talking and singing to him and remembering aloud all of the good times they’d had together. Indeed, Maria partially credits herself for Sam coming out of his coma, and was overjoyed that he “came back” to her. He was eventually released to a nursing home to fully recover, but Maria was not happy with the care and has since switched him several times to other facilities. Twice more he was put on life support, and after the third time, Sam supposedly told Maria, “don’t help me anymore,” which meant, Maria says, that he did not want to “go through all of that again.” Somewhat reluctantly, then, Maria agreed to put him in a hospice program at his doctor’s suggestion.

Maria seems satisfied with his current nursing care, but she is very sad and depressed, especially as her son, Roy, is also dying of cancer. She says that she is “utterly heartbroken” and doesn’t know if she has the “strength to go on.” Sam, meanwhile, does not appear agitated or distressed. His cognitive level appears to be very poor, but Maria claims he is still quite alert and responds intelligently to her, though the staff has not specifically witnessed this. Currently, he remains mostly in bed or in one of the day rooms. He does not interact with the other residents, as Maria rarely leaves his side and tends to speak for him.

(Originally written: November 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post A Wonderful Father and an All-Round Outdoors Man appeared first on Michelle Cox.

August 13, 2020

Forever His Bride . . .

Esther Andrews was born on February 14, 1910 in Chicago to Lester Simonis and Nellie Baird. It is thought that Lester was an immigrant from Latvia and that Nellie had been born in Scotland. According to family legend, shortly after Nellie arrived in America as just a baby, both of her parents died, and she was placed in an orphanage in Chicago. At fifteen, she began working as a maid, where she met Lester Simonis, who delivered the daily milk to the house she was employed at. Lester eventually proposed to Nellie, who accepted him, and they were married soon after. Nellie quit her job to care for their eventual four children: Verla, Clifford, Stella and Esther, while Lester continued working as a milkman. When Esther was just a baby, however, Lester died, though no one in the family seems to remember of what. Nellie took in washing for a while to make ends meet, and eventually ended up marrying Daniel Juric, a kind man, who worked in various factories around the city.

Esther Andrews was born on February 14, 1910 in Chicago to Lester Simonis and Nellie Baird. It is thought that Lester was an immigrant from Latvia and that Nellie had been born in Scotland. According to family legend, shortly after Nellie arrived in America as just a baby, both of her parents died, and she was placed in an orphanage in Chicago. At fifteen, she began working as a maid, where she met Lester Simonis, who delivered the daily milk to the house she was employed at. Lester eventually proposed to Nellie, who accepted him, and they were married soon after. Nellie quit her job to care for their eventual four children: Verla, Clifford, Stella and Esther, while Lester continued working as a milkman. When Esther was just a baby, however, Lester died, though no one in the family seems to remember of what. Nellie took in washing for a while to make ends meet, and eventually ended up marrying Daniel Juric, a kind man, who worked in various factories around the city.

Esther received a somewhat sketchy education, only attending school through the fourth or fifth grade. She quit school and got various odd jobs until she found a permanent place at the Excelsior Seal Furnace Company on Goose Island at age thirteen. Her job was to pack the parts in boxes to be shipped out.

When she was nineteen, however, her mother, Nellie, died unexpectedly of the flu. Esther was the only one still left at home, so for a while she and her grieving stepfather, Daniel, tried to make the best of it. Daniel, however, went into a deep depression, and Esther found it hard to cope with him just on her own. She appealed to her older sister, Verla, who agreed to take in both Esther and Daniel, provided that Esther “do her part” around the house. Esther, eager to be relieved of the sole responsibility of caring for their stepfather, agreed to her sister’s conditions, but soon lived to regret it. Verla gave Esther long lists of chores that she was expected to complete each day, including gardening, in addition to her working at Excelsior Seal.

This routine continued for nine long years until Daniel met another woman, Mary Budny, at a dance. The two married six months later, and Daniel finally moved out of Verla’s home, leaving Esther behind, who, at age 28, was beginning to think life had passed her by. She hated living with Verla and her husband, Bob, and resented being “their slave,” but she couldn’t see any other option.

Esther had nearly resigned herself to being a spinster until one day, September 14, 1938, to be exact, a young man by the name of Glenn Andrews walked into Excelsior Seal Furnace Company looking for a job. Glenn was hired on the spot, and it was Esther’s job to show him around. The two took a liking to each other, and before the day was out, Glenn asked her out on a date. Esther excitedly said yes, and Glenn took her to the Aragon ballroom.

Esther and Glenn dated for four years before they were married on January 22, 1944. Four days later, Glen left for the war. He served for 27 months in Japan and the Philippines and says that it was the many, many care packages of cookies and candy and letters from Esther that got him through. When he came back, miraculously “safe and sound,” he and Esther had to “relearn each other” all over again. Esther had spent the war still living with Verla and Bob, who had not altered their treatment of her despite the fact that she was now a married woman.

When he returned, Glenn got his job back at Excelsior, and he and Esther rented a little apartment on Sedgewick. Their neighbors were Ada and Dieter Kahler, a German couple with three kids, whom they got to know very well. Eventually the four of them went in together and bought a two-flat. Both families lived there for the next 27 years and became best friends. Glenn and Esther never had any children, so they enjoyed helping with and watching Ada and Dieter’s children, whom they became very close to over the years.

Glenn and Esther were very active in the United Steel Workers Union and served on many, many committees. They enjoyed visiting with friends and playing poker and loved going to see movies. Their biggest passion, however, was traveling. They spent every vacation traveling, and in 1979, when Esther finally retired from Excelsior, after working there for 54 years, they decided to travel full-time. They spent the next 14 years traveling to such places as New York, Wisconsin, Mexico, Lake Louise, Niagara Falls, New Orleans, Florida, Mt. Rushmore, California, Hot Springs, the Grand Canyon, and many, many more. They traveled by car, train, and even bus on some occasions.

After so many years of enjoyment with each other, “Esther began to change,” says Glenn, in the early 1990’s. She became increasingly confused and was often found wandering the neighborhood. Also, says Glenn, she put on “layers of layers of clothes” and even once chased him through the house with a knife. Unable to understand her diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, Glenn tried to care for Esther himself for about eleven months before he finally gave in to the doctor’s suggestion that he admit her to a nursing home, heartbreaking though it was for him to be separated from her.

Technically, Glenn still lives in the two-flat that he and Esther purchased with the Kahlers, though only he and Ada are left, Dieter having died years ago and their children having since moved away, but he prefers to spend his days and evenings at the nursing home. Here he sits with his beloved Esther, 365 days a year, wheeling her about the home, taking her outside to sit in the gardens, or bringing her to various activities. Esther does not really participate in any of the home’s events, however, and just sits quietly with her eyes closed. If asked a question, she usually gives a garbled, nonsensical answer.

Glenn does the talking for her as he holds her hand. He knows every single resident and staff member. He loves to talk to whomever will stop long enough and especially enjoys telling stories of he and Esther’s traveling days. When the staff ask him why he doesn’t just make it official and move here, too, Glenn says that he couldn’t do that to poor Ada. But he remains devoted to Esther, coming every day and always lovingly calling her “my bride,” though he often sadly states that she is just a shell of the lovely, sweet woman she once was.

(Originally written May 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available AUDIO !

The post Forever His Bride . . . appeared first on Michelle Cox.

July 23, 2020

“I’ve Had a Lovely Life.”

Sadie Davis was born on December 2, 1920 to Ervin Olmskirk and Caroline Fredericks in Clarkson, Nebraska. Ervin worked in a bank, and Caroline cared for their ten children: Sadie, Irving, Louis, George, Thelma, Rose, Francis, Fred, Ruby, and Gladys.

Sadie Davis was born on December 2, 1920 to Ervin Olmskirk and Caroline Fredericks in Clarkson, Nebraska. Ervin worked in a bank, and Caroline cared for their ten children: Sadie, Irving, Louis, George, Thelma, Rose, Francis, Fred, Ruby, and Gladys.

Sadie was a bright child and after finishing high school, won a two-year scholarship to Wayne State College in Wayne, Nebraska. This was following the Great Depression, however, so when the two years were up, Sadie could not afford to stay longer, though she dearly loved her college experience and dreamed of becoming a teacher. She contemplated ways that she could earn the money herself, but before she could come up with any answers, she received word that her father had been killed in a freak accident, which caused her to have to hurry home. Ervin had apparently been out trimming trees when a large branch fell on him, crushing his skull and killing him instantly. He was only forty-six years old. At the time of her father’s death, Sadie was nineteen and her youngest sibling had just turned one. Sadie then naturally gave up all hopes of furthering her education and began looking for a job to help support her mother.

The family had barely time to recover from Ervin’s death when they received word that Ervin’s brother, Anthony, who was living in Chicago, had also died. With her husband recently deceased, ten children to take care of and little money, there was no way that Caroline could make the journey to Chicago for her brother-in-law’s funeral, though she fretted endlessly about who would represent the family. Finally, she decided that she would send Sadie with an aunt and uncle who lived in nearby Omaha and who were planning on travelling up to the funeral on the train. Sadie was chosen because she hadn’t yet found a job and because she was the same age as Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom’s only child, Imogene, who was also making the journey. That way, Aunt Betty said, Imogene would have someone to talk to.

On the long train ride to Chicago, Sadie and Imogene enjoyed getting to know each other again, having not seen each other for several years. Sadie told Imogene all about her college days at Wayne State, and Imogene told her all about living in the big city of Omaha. Together the girls schemed that if they could somehow find jobs in Chicago while they were there for the funeral, they might be allowed to stay.

The funeral, it turned out, was all the way north of the city in a small vacation village called Fox Lake. Many relatives showed up from out of town and rented small cottages rather than staying in hotels. Sadie and Imogene began to look for work right away, though not much could be found in Fox Lake. As it turns out, Imogene went to the beach one day without Sadie, who stayed behind in the cottage because she was feeling ill. Later in the day, feeling a little better, Sadie ventured out doors on her own and was intrigued by a young man working on a sail boat in the yard next door. The two began talking over the fence and fell into an easy conversation. His name was Lowell Davis.

Eventually, after many days of talking over the fence, Lowell asked Sadie out on a date, and she accepted. They had a wonderful time together and found it very easy to talk, but their new relationship threatened to be over just as it was beginning, as Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom were planning to return to Nebraska soon. Lowell decided drastic measures were in order, so he sold his boat to buy Sadie an engagement ring and proposed to her.

Sadie said yes and arranged to stay with other relatives in the city until the wedding could be planned. She found a job downtown in a millinery shop, and offered to help Imogene find something, too. Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom refused to hear of any such nonsense, however, and despite Imogene’s pleading, insisted that she return to Omaha with them.

Eventually Sadie and Lowell married and moved to the northwest side of Chicago. When WW II broke out, Lowell dutifully joined the navy. Left alone, Sadie considered moving back to Nebraska to live with her family for the duration of the war. In the end, however, she decided to stay in Chicago and wait for Lowell to come back. When Lowell eventually returned from the war, miraculously unharmed, he got a job as a loan officer at a bank, oddly like her father, Ervin. Sadie continued working in the millinery shop until her first baby was born. In all, Sadie and Lowell had four children, all girls: Shirley, Gloria, Brenda and Virginia. Though she mostly remained a housewife, Sadie sometimes worked as a substitute teacher and also taught CCD classes at her church. She was also very involved in the Girl Scouts and other community organizations. Her hobby was writing the family history going generations back.

Lowell died in 1973, after which Sadie continued living alone, though she was very active. Only recently, when she has been diagnosed with Hodgkin’s, has she begun to need help. She was admitted to the hospital due to complications with her condition and was then discharged to a nursing home. All of her daughters live out of town, except Shirley, who visits regularly and is very concerned for her mom. She puts on a brave face in front of Sadie, but she frequently cries to staff from the guilt of not being able to care for her mom at home.

Sadie, meanwhile, is making an excellent transition, though she is sometimes very weak and tired. She enjoys intellectual conversations or sitting and watching television with other residents. She does not appear distressed or upset, but says that “life is what you make it. I’ve had a lovely life.” Her daughter, Shirley, concurs, relating that her mother has always been a very positive person, no matter what the circumstance.

(Originally written: March 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

Also available on AUDIO!

The post “I’ve Had a Lovely Life.” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

June 11, 2020

“She Was Happiest With a Drink in Hand.”

Vlasta Di Stefano was born on January 21, 1910 in Chicago to Bela Hrabe and Lazar Dragic. Bela was an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Lazar emigrated from Yugoslavia. The two apparently met at Ellis Island and, though they initially went their separate ways, they wrote letters to each other for the next year or so. Eventually, they somehow met up again and married, settling in Chicago on Harding Avenue. After a few years, however, they left the city and moved to a farm in Minnesota. Besides farming, Lazar worked delivering lumber, and Bela cared for their seven children: Adam, Yvonne, Denis, Vlasta, Dusan, Emil and Pavla.

Vlasta Di Stefano was born on January 21, 1910 in Chicago to Bela Hrabe and Lazar Dragic. Bela was an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Lazar emigrated from Yugoslavia. The two apparently met at Ellis Island and, though they initially went their separate ways, they wrote letters to each other for the next year or so. Eventually, they somehow met up again and married, settling in Chicago on Harding Avenue. After a few years, however, they left the city and moved to a farm in Minnesota. Besides farming, Lazar worked delivering lumber, and Bela cared for their seven children: Adam, Yvonne, Denis, Vlasta, Dusan, Emil and Pavla.

Vlasta attended grade school, but at age thirteen, she decided to move back to Chicago, where her older sister, Yvonne, and her husband had since moved to. Vlasta lived with them and got a job at Union Linen Supply and there met her future husband, Ruben Alvardo, a Mexican immigrant. Ruben liked Vlasta immediately and often took her on picnics to a picnic grove at Devon and Milwaukee, which, at that time, was still a wooded, rural area. He eventually proposed to Vlasta, and they married when she was just nineteen.

Ruben continued working at Union Linen, but Vlasta quit once she became pregnant with their first child. Ruben and Vlasta had a total of six children: Viola, Kenneth, Raymond, Carol, Dolores and Jerry. When Jerry was a toddler, Vlasta decided to go back to work. Union Linen Supply had no openings, however, so she instead got a job at a company called Cromane, which did silver plating.

According to her daughter, Viola, Ruben and Vlasta were very private people. They did not have friends, nor did they associate with either of their families. They even refused to go to any school functions, including their own children’s graduations or holiday shows. Their only pastime, says Viola, was drinking. In fact, when Vlasta decided to return to work, she apparently dumped all of the household cleaning, management and cooking unto Viola, who was roughly eleven at the time. From that point on, Viola became the mother-figure for the whole family and remains so even today.

Tragically, in July of 1950, Ruben was hit by a car and killed while walking home from work. He was not yet 50 years old. Vlasta continued working, doing her best to make ends meet and eventually met and married David Di Stefano. She only had about ten years with David, however, before he died of cancer. After that, Vlasta lived alone, watching her neighborhood slowly decline, and was attacked twice coming home from the shops. She put her name in to get a place in North Park Village, but had to wait ten years for a spot to open up.

When Vlasta did finally move into the North Park Village senior apartments about seven years ago, she was still relatively independent, but as time has gone on, she has relied more and more on Viola to again help her with cleaning, laundry and shopping. Recently, though, things have become worse, with Vlasta not being able to care for herself at all. Viola has been in the habit for the last several months of going to Vlasta’s apartment twice a day to feed her and clean up urine and feces that is usually found on the floor or furniture. Viola has been beside herself with worry, as she has often come to the apartment and found the stove on and pans burnt through. Fearing that she would possibly have a nervous breakdown from the stress of the situation, Viola finally decided to admit Vlasta to a nursing home.

Viola, in the role of mother since age eleven, feels incredible guilt at not being able to still care for Vlasta, but they are both adjusting well to the new arrangement. Viola predicted that Vlasta would be extremely angry at being placed in a home, and was therefore pleasantly surprised by Vlasta’s easy transition. Vlasta is confused at times and does not talk a lot, but she enjoys sitting among the other residents. Though not always eager to participate in activities, she very much likes to watch what is going on, perhaps a life-long behavior. Viola claims that her mother never had any hobbies and never wanted to “get involved.” She says that Vlasta watched everything from afar. She was content, but “never really that happy, even on birthdays or holidays.” She was “very much a loner and had a hard time fitting in.” She was happiest, Viola claims, when she “had a drink in her hand.”

(Originally written May 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “She Was Happiest With a Drink in Hand.” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

June 4, 2020

Reunited . . . Christmas 1933

Hana Jezek was born on September 25, 1922 in Brezova, Czechoslovakia to Bartholomew Jezek and Irena Vedej. Bartholomew was a soldier and was always on the move with the army. It was in one of the little villages he traveled through that he met Irena and fell in love with her. They eventually married and had two children: Hana and Bartholomew, Jr., or Bart, as he came to be called.

Hana Jezek was born on September 25, 1922 in Brezova, Czechoslovakia to Bartholomew Jezek and Irena Vedej. Bartholomew was a soldier and was always on the move with the army. It was in one of the little villages he traveled through that he met Irena and fell in love with her. They eventually married and had two children: Hana and Bartholomew, Jr., or Bart, as he came to be called.

In 1929, when Hana was seven and Bart five, the situation in Czechoslovakia was so bad that Bartholomew and Irena decided to try a new life in America. Bartholomew had brothers and sisters who had already made the journey and had settled in Chicago. They were constantly urging Bartholomew and Irena to join them, and, finally, the two decided to go. Once the decision was made, one of Bartholomew’s brothers wrote and advised them to come without the children, as they would be unburdened that way and could make more money. At first, Irena refused to leave Hana and Bart, but after much pleading, Bartholomew finally convinced her to leave them with a grandmother. Irena cried and sobbed when it was time to leave and was often depressed and inconsolable on the ship bound for America.

Once in Chicago, Bartholomew got a job with his brother at the Brach Candy Company on the night shift, and Irena found work at S. K. Smith, which was a lithography company. After four long years of working, they were finally able to send for Hana and Bart, who arrived in America on December 15, 1933. They traveled on a ship in the care of several other people from their village who were immigrating, too. Irena was overjoyed to see her children, never having forgiven herself for leaving them behind. Irena always said that it was their best Christmas ever. From that point on, she spoiled her children completely.

By 1940, the family had saved enough to buy a little house on Karlov Avenue, where Hana has lived ever since. When she graduated from high school, Hana got a job at the Zenith radio factory and worked there for 42 years, never missing a day. Her parents were similar in that they remained at the original jobs they found upon arrival in Chicago until the day they retired. Hana says that her family was just like that. “Once they had a thing,” she says, “they always stuck to it,” whether it was a job or a house or a car. “They didn’t like change.”

Hana and her brother, Bart, were very close as children and remained so as adults. When WWII broke out, Bart enlisted in the army, and Hana wrote to him every week with the news from home. When he came back from the war, he married the girl who lived down the street, and they eventually bought a house on Karlov as well. Hana loved her sister-in-law, Dorothy, and was very involved in the lives of her nieces and nephews.

Hana herself never married, saying that “the right fellow never came along,” though Bart is of the opinion that she simply didn’t want things to change. Whatever the reason, Hana instead devoted herself to working and to her hobbies, which included travel. Hana loved travelling and went all over the United States with her mother. Bartholomew never wanted to go, saying that he had traveled enough as a soldier when he was a young man. He called himself “a homebody,” preferring to stay and take care of the house while his wife and daughter went on their trips. He adored both of them and always had a hot meal waiting for them when they returned from their travels.

Hana enjoyed knitting and crocheting and was very active in their church, Trinity Lutheran. Later in life, she developed a passion for going to the movies and went to see all the new films, either with girlfriends or her mother, at the Gateway, the Karlov, the Tiffin or the Logan. Hana lived with her parents her whole life on Karlov Avenue, caring for them as they aged until they died in their eighties. Bartholomew died of congestive heart failure at age 82, and Irena died after a stroke at age 86 in 1990. Since then, Hana has lived alone in the house, though Bart and his family live close by.

Hana very recently began experiencing chest pains and was hospitalized with what she thought was a heart problem. It turned out to be a respiratory condition, however, requiring oxygen, and her doctor felt she should be admitted to a nursing home until her condition clears and her health improves. Hana agrees with her doctor’s advice, but she fully plans to return to her home on Karlov as soon as she can. Bart and his wife, Dorothy, likewise feel this is a realistic goal and are very supportive. Not only do they visit Hana regularly, but their children and even grandchildren frequently come to visit “Great Aunt, Hana.” They appear to be a very loving family and concerned with Hana’s well-being and comfort.

Until she can go home, Hana is patiently biding her time, careful to follow her doctor’s instructions to the letter. She is very cheerful and friendly, and seems to genuinely like talking with the other residents and participating in almost every activity the home has to offer.

(Originally written: December 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Reunited . . . Christmas 1933 appeared first on Michelle Cox.

May 21, 2020

Many Sisters Named Aurora

Aurora Sienkiewicz was born on April 5, 1911 to Giovanni and Rosa Corvi, both of whom grew up in the same small village in Italy. Giovanni’s and Rosa’s families lived near each other, and the two of them often played together as children. The story goes that one day when Giovanni was passing by, Rosa pointed to him and told her mother that someday she was going to marry Giovanni. It was a prediction that came true, and when they both turned eighteen they married and soon had a son, Marco.

Aurora Sienkiewicz was born on April 5, 1911 to Giovanni and Rosa Corvi, both of whom grew up in the same small village in Italy. Giovanni’s and Rosa’s families lived near each other, and the two of them often played together as children. The story goes that one day when Giovanni was passing by, Rosa pointed to him and told her mother that someday she was going to marry Giovanni. It was a prediction that came true, and when they both turned eighteen they married and soon had a son, Marco.

Times were hard in the village, however, and there was little work. So when Marco was five years old, Giovanni decided to go to America and look for work a new life for them. Once in New York, he happily soon found a job and then immediately sent for Rosa and Marco to join him. The two of them came by ship with many people from their village, so they were not alone on the journey. Once Rosa and Marco arrived in New York, Giovanni found them an apartment in Brooklyn. Rosa got pregnant several times, but she always miscarried. They were all girls, and Rosa named them all Aurora after Giovanni’s mother, as was the custom.

After a few years in New York, Giovanni got restless and moved the whole family to Louisiana, where another son, Frank, was born. Again, the family settled down, but unfortunately Giovanni could not find any work, so they decided to go to California. They took a train to Chicago and were delayed there for some reason for almost a weak. In that time, Giovanni stumbled upon a good-paying job at a cigar factory, so they decided to stay. Rosa also did piece work at home, mostly sewing buttons onto trousers. In Chicago, she was finally able to carry a girl to term and once again named her Aurora. Two years later, Rosa had her fourth and last child, Vincent.

Aurora went to school through the 8th grade and then got a job in a paper box factory at age fourteen. She worked in various factories during her teen years, but she especially liked working at a stencil factory because they got to use chemicals. She found chemistry very interesting, and she became friends with one of the factory chemists, John Petronka. Aurora says that she is pretty sure John had a crush on her, but he was already engaged to someone else. Thus, he introduced her to his good friend, Thaddeus Sienkiewica. The two of them hit it off right away, and after dating for just six months, Thaddeus proposed. Both Giovanni and Rosa were not thrilled about their only daughter marrying a Pole instead of an Italian, but they allowed them to get married anyway.

Thaddeus worked for Western Oil, a job he kept for forty-five years, and Aurora stayed home to care for their four children: Gloria, Phyllis and the twins, Roman and Roy. Like her mother before her, Aurora had many miscarriages over the years, and finally, after the twins were born, her doctor advised her to have a hysterectomy, to which Aurora agreed. When all of the children were in school, Aurora decided to go back to work and got a job as a kitchen aide in various hospitals.

Sadly, Aurora’s marriage was not a happy one, as Thaddeus turned out to be an alcoholic. Aurora says that this is why she was always a loner and had no friends or hobbies. “I had too many problems at home to worry about,” she says of that time. Having no one else to turn to, Aurora would sometimes confide in her mother, Rosa, regarding her marital woes, but Rosa, and Giovanni, as well, refused to ever talk badly about Thaddeus. “We told you you should marry an Italian,” they often scolded her, and told her that she would just have to put up with it.

Finally, however, Aurora could no longer stand to witness how Thaddeus’s behavior was affecting the children, so she separated from him. It was an extremely difficult thing to do, especially as her parents disapproved of divorce. They refused to support her, either financially or emotionally. Thaddeus moved into his own apartment, and though Aurora had some contact with him over the years, she pretty much raised the family on her own.

After her divorce, Aurora still stayed home much of the time in the evenings, but felt freer to make friends and invite them over. Occasionally, she would venture out to a movie or bingo at St. Philips, where she was a faithful parishioner. Only once did she take a trip, which was to go to California to see her brother, Vincent. She continued working as a kitchen aide until she was in her sixties.

When Aurora was in her mid-seventies, her son, Roman, died at age forty-five of complications due to his colitis condition. He was not married, and “didn’t take care of himself as he should have,” Aurora explains. “He lost the will to live.” Aurora was nearly broken by his death and refused to ever speak his name after the funeral was over. She still mourns him even now, she says.

Up until very recently, Aurora was living alone and was still active and able to care for herself. About a year ago, however, she had a small stroke and fell. As Phyllis is the only one of Aurora’s children still living in the area, much of the burden of caring for Aurora fell to her. The staff at the hospital suggested that Aurora be discharged to a nursing home, and Aurora reluctantly agreed with this decision.

While Aurora seems resigned to her fate, Phyllis does not. Because of her own health problems, she cannot care for Aurora at home and seems to feel very guilty about this. In just the last year, Phyllis has changed nursing homes for Aurora three times, as Phyllis—not necessarily Aurora—has been very unhappy with each placement, including the current one. Phyllis frequently lashes out at the staff, accusing them of a variety of things and can even be verbally abusive at times. Already she has threatened to remove Aurora yet again.

Meanwhile, Aurora seems not aware of Phyllis’s distress. She appears to be content, her favorite activity being bingo. At times she is confused and believes that her clothes are missing, which causes her to complain repeatedly to the staff. Once she becomes upset, she then tends to bring up Thaddeus and the anger she still feels towards him. “He’s living alone, free and easy, and here I am!” she will say, over and over. Normally, however, she is a pleasant woman who enjoys having conversations with the other residents or watching TV with them.

(Originally written August 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Many Sisters Named Aurora appeared first on Michelle Cox.

April 23, 2020

She Crossed the Ocean to Find Her Love

Erna Lindner was born on May 27, 1904 on a farm in Austria, which later became part of Czechoslovakia. Her parents, Alban Hager and Sylvia Kainz, worked “night and day” on the farm, and when Alban had to fight in the First World War, the running of the farm fell on Sylvia and their five children: Alban, Jr., Theresa, Walter, Erna and Martin. Erna says that it was “a very, very, very had life. Very difficult,” even after her father came back from the war, though, she says, “we always had plenty of good, fresh food.” Erna says that no one really went to school, except Sunday school, and as young people they never went out and socialized, as there was always too much work to do on the farm.

Erna Lindner was born on May 27, 1904 on a farm in Austria, which later became part of Czechoslovakia. Her parents, Alban Hager and Sylvia Kainz, worked “night and day” on the farm, and when Alban had to fight in the First World War, the running of the farm fell on Sylvia and their five children: Alban, Jr., Theresa, Walter, Erna and Martin. Erna says that it was “a very, very, very had life. Very difficult,” even after her father came back from the war, though, she says, “we always had plenty of good, fresh food.” Erna says that no one really went to school, except Sunday school, and as young people they never went out and socialized, as there was always too much work to do on the farm.

Erna did meet a boy, however, named Theo Lindner, at church. Her only time to see him was on Sunday afternoons when he would sometimes come to the Hager farm to visit and talk with Erna’s parents. As time went on, all three of Erna’s older siblings left for America. Eventually, Theo left, too. From that point on, Erna was desperate to get to America to be with Theo. Finally, when she was 19, in 1923, her parents arranged for her to travel with a large group of people from their town who were all making the journey together. Only her younger brother, Martin, remained behind to care for the farm and their parents.

Erna stuck with the group on the long ship ride over and then traveled alone to Chicago, where she was reunited with her sister, Theresa. Erna immediately found a job as a waitress at a restaurant at Cicero and 26th and then began looking for Theo. She finally found him, and within 3 months of arriving in America, she married him. They had a small wedding dinner for immediate family only and went to live with Theresa until they could get someplace of their own. Theo worked as a tailor, and Erna eventually got a job in a factory, which she stayed at for 31 years.

Erna and Theo finally got their own place, which was a two-room apartment, and later saved enough to buy a two-story house. During the depression, however, they found they couldn’t pay the mortgage, so they lost the house, which, Erna says, broke Theo’s heart. Erna says they had “a nice life together,” but that Theo “never really go over” losing the house. In fact, she believes that it contributed to his early death at age fifty in 1950. Apparently, he went to sleep one night and never woke up. They had been together for twenty-seven years and had three children: Sarah, Ruth, and Paul. Theo lived to see both daughters married, but died during Paul’s engagement.

Erna continued working, even after Theo’s death, supporting herself and helping with her grandchildren. She was an extremely hard worker, never taking time for herself or any hobbies, except for dancing. She loved music and continued to go to dance halls until she was seventy-five years old, at which point, she says, her legs “finally gave out.” She never traveled, except for her one-time trip from Austria/Czechoslovakia to Chicago. After that, she says, she “never once stepped foot out of Chicago.”

In her later years, unfortunately, more sadness occurred for Erna. Her daughter, Sarah, became ill, and Erna spent the last fifteen years of Sarah’s life going to hospitals to visit her whenever she had to be admitted and helping her with her children, Vincent and Fanny. Not only was this difficult to deal with over the years, but then Vincent committed suicide, leaving behind two children of his own and a wife, who was eight months pregnant at the time. Erna explains that Vincent died in a car “accident”—that he was in a closed garage and died of “fumes.” She does not equate his death with suicide. Whether she cannot face the truth or was never really told the truth, is unclear. Not long after Vincent’s suicide, Sarah died, too. And shortly after that, Erna’s son-in-law, Ralph, (her daughter, Ruth’s husband) died as well.

Despite all of this loss and tragedy, Erna does not seem bitter or depressed. She often says, “What can we do?” With Sarah deceased and her son, Paul, living in Florida, Erna became more and more dependent on her youngest daughter, Ruth. Since her husband, Ralph’s, death, however, Ruth has been having her own increased health problems, as well as depression, and has found it harder and harder to care for her mother. Eventually, she broached the subject with Erna of going to a nursing home, which Erna was surprisingly accepting of. Erna herself chose the Bohemian Home for the Aged, because she was familiar with it, as she had often attended the Home’s annual Memorial Day picnic, which the community at large was invited to participate in.

Erna has thus made a very smooth transition. “I’m happy with this place. It’s clean,” she says and is very proud of the fact that she has learned her way around the facility so quickly. “I’m not dumb,” she says. “I’m just old. I don’t have anybody, only my daughter, and I wanted to be with people, so I came here. I’ve had a hard life, but you have to take care of yourself. You can’t depend on anyone else to make you happy.”

(Originally written: May 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post She Crossed the Ocean to Find Her Love appeared first on Michelle Cox.

April 16, 2020

The Secret to Happiness: “Be Content With What You Have.”

Estelle Oberst was born in Chicago on October 20, 1900. Her father, Edwin Larsen, was an immigrant from Norway, and her mother, Theresa Amsel, was an immigrant from Germany. The two somehow met after they arrived in Chicago and married not long after. Estelle does not remember exactly where her father worked, but she thinks it may have been in a factory. Her mother cared for their eight children (Gunther, Edward, Agnes, Hans, Felix, Helen, Estelle and Ludmilla), all of whom made it to adulthood except one, Ludmilla, who died in the flu epidemic. At age 94, Estelle is the only member of her family still alive.

Estelle Oberst was born in Chicago on October 20, 1900. Her father, Edwin Larsen, was an immigrant from Norway, and her mother, Theresa Amsel, was an immigrant from Germany. The two somehow met after they arrived in Chicago and married not long after. Estelle does not remember exactly where her father worked, but she thinks it may have been in a factory. Her mother cared for their eight children (Gunther, Edward, Agnes, Hans, Felix, Helen, Estelle and Ludmilla), all of whom made it to adulthood except one, Ludmilla, who died in the flu epidemic. At age 94, Estelle is the only member of her family still alive.

Estelle attended two years of high school and then quit to begin working as a punch press operator at Sunbeam. When she was nineteen, a new foreman started at work, Joseph Oberst, who took an immediate liking to Estelle. Estelle was not interested in him, but he continued to pester her until she finally agreed to go on a date with him. She was apparently not impressed, but Joseph continued to pressure her to go out with him, which Estelle would reluctantly do from time to time. Her friends were shocked, then, when one day she announced that she was going to marry him and would not explain why.

As soon as they were married, Joseph demanded that Estelle stay home to be a housewife, which Estelle obediently agreed to. She eventually had two children, Charles and Joseph, Jr., whose birth she almost died during because he was so large. Estelle’s marriage to Joseph was apparently an unhappy one, and she describes Joseph as “a miserable man.” Still, she tried to create a nice home for her two little boys.

Besides caring for her children, Estelle was devoted to her church, First Congregational, and was the oldest living member for many years. She was very active there throughout her entire life and held a variety of volunteer positions, including sitting on the board of many committees. She also ran craft bazaars, organized bake sales, was a leading member of the sewing circle, and cooked and cared for many of the sick and elderly in the parish. In fact, many, many elderly were able to stay in their homes a few extra years because of Estelle. Estelle even took in her mother-in-law, Margaret, though she was a very angry, bitter woman. None of Margaret’s other children wanted anything to do with her, so Estelle offered their home to her and lovingly cared for her until she died.

Estelle spent most of her life devoted to caring for others, but in her seventies, she began experiencing her own series of losses. The first was the death of her son, Joseph, Jr., who died suddenly at age 48 in 1976. He had never married. Then, a year later, her husband, Joseph, died, followed by her other son, Charles, who left behind a wife, Virginia, but no children. So in the span of two years, she lost her husband and both sons – her entire family, except her daughter-in-law. It was a very difficult time for Estelle, but she continued to try to have a positive attitude.

As the years went along, she came to rely more and more on Virginia, who likewise became increasingly devoted to Estelle and very protective of her. Virginia describes Estelle as being “a tough woman with a very strong will to live and a very positive attitude toward life.” Estelle, she says, would do anything for anyone and “has a heart of gold.” Virginia says that Estelle would never go to someone’s house without bringing them something, usually something she baked or sewed. She says she dealt with her many losses in life, including her horrible marriage, by constantly reaching out to others. If she was experiencing something sad, she would seek out someone worse off than herself and try to comfort them.

Estelle was still very active (and drove herself everywhere!) up until the age of eighty-eight when she fell and broke her hip. She was temporarily hospitalized but was able to go back to her own home eventually. She continued to have falls for the next four years and ended up in the hospital again in 1992 after a particularly bad one. Though Virginia has been helping Estelle for several years with cleaning and errands, she recently began to feel that she could no longer care for Estelle full-time, as she herself is in her seventies now with her own health problems, including a bad back. Neither of them could afford the kind of home health care Estelle would need in order to stay in her home, so Virginia made the decision that Estelle should be released from the hospital to a nursing home.

Estelle is not particularly happy about her placement and believes that she will someday return home. She is a very agreeable, sweet person, but is very hard of hearing. This, plus the fact that her attention span and memory are poor, makes it hard for her to participate in activities or befriend other residents. She enjoys one-on-one attention from the staff, however, and will converse as much as she is able. Meanwhile, Virginia tries to visit as often as she can.

When asked about her life, Estelle says that is was a happy one, though she still misses “my boys.” When asked what her secret to happiness is, she says that it has been her faith and that you have to “be content with what you have. There’s always someone worse off than you that can use a hand.”

(Originally written: May 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post The Secret to Happiness: “Be Content With What You Have.” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

April 9, 2020

“More Like Sisters”

Doris Gockel was born on March 15, 1934 in Chicago. Not much is known of Doris’s early life, except that her mother, Gertrude Molnar, who was of Hungarian descent, had Doris when she was very young. About a year after Doris was born, Gertrude married a man named Walter Sands, who was not Doris’s birthfather, but who came to love Doris as his own child. Gertrude and Walter never had any children together, so Doris was everything to them.

Doris Gockel was born on March 15, 1934 in Chicago. Not much is known of Doris’s early life, except that her mother, Gertrude Molnar, who was of Hungarian descent, had Doris when she was very young. About a year after Doris was born, Gertrude married a man named Walter Sands, who was not Doris’s birthfather, but who came to love Doris as his own child. Gertrude and Walter never had any children together, so Doris was everything to them.

Doris went to school until the tenth grade and then quit to begin working. Over the years she had a variety of jobs, though she says that her job at an ice cream parlor was her favorite. Doris did not go out much, preferring to be at home with Gertrude and Walter, but one night her friends persuaded her to come to the St. Patrick’s Night Ball at the Merry Garden Ballroom. After much urging on the part of her friends, Doris finally agreed to go, since it was very near her birthday, and it was there that she met a boy named Willie Gockel. The two started dating and married very quickly. Doris was just seventeen, and Willie was eighteen. Willie worked as a plasterer, then as a carpenter, and eventually had his own little contracting business, while Doris stayed home and cared for their three children: Linda, Susan and David.

Doris says that “everything was fine in a way” between her and Willie, but after about twenty years together, she says that Willie started “drinking and going out with the guys.” Eventually he “ran away with some woman.” Doris’s son, David, does not know all of the details of went wrong in his parents’ marriage, but confirms that his father left when he was around twelve years old. Doris had no choice but to find a job, then, and began working as a barmaid at Lakeside Tavern. Doris worked there for over thirteen years and made a lot of friends, many of whom became like a family to her. It was during that time, though, that Doris began to drink a lot, which, says David, was perhaps “just part of the job.”

Despite her drinking and her seedy job at the bar, David says that Doris loved decorating and fixing things up around the house. She had a talent for decorating and had the further talent of being able to do it “on hardly any money at all.” Her favorite thing to do was to go to garage sales with her mother, Gertrude, to find things they could refurbish. They also both shared a love of gardening, particularly of flowers, and could both “make sticks grow.” Doris and his mother were very close, David reports. “They were more like sisters than mother and daughter.”

Unfortunately, in the early 1980’s, Doris suffered a brain aneurysm and was hospitalized for a very long period of time. According to David, she nearly died on three occasions, each time having to be revived by the staff. Doris made it through, but it was a long recovery, during which time she had to relearn everything. Eventually Doris was able to go home and live independently, though her vision and equilibrium were not perfect, and, according to David, she has never been the same mentally. She has always been just “a little bit off” since the whole ordeal, prompting David and his wife, Sharon, to get into the habit of checking on her several times a week in order to help her with various tasks.

Doris was able to manage this way for the next ten years or so until the early 1990’s when her daughter, Susan, separated from her alcoholic husband and went to live with Doris to “take care of her.” David and Sharon think that this was the beginning of the end for Doris, as Doris then became subjected to what they call Susan’s “bad influence.” Ever since the aneurysm, Doris had given up drinking, but when Susan came back to live with her, she started up again. Likewise, David and Sharon believe that Susan, whom they say is also unstable, was probably not providing Doris with balanced meals or regulating her medication correctly. Susan became very protective of Doris during this time and was resentful if David or Sharon tried to still help, claiming that it wasn’t necessary and that they were “interfering.”

Things went from bad to worse when Susan came home one day and found Doris out in the yard, unconscious. It is not known how long she had been laying there, but the doctors concluded that she had had a stroke. When she eventually recovered in the hospital enough to be released, David and Sharon thought it obvious that she should go to a nursing home, but Susan disagreed. David attempted to call his other sister, Linda, to get her involved, but since she had been estranged from the family for a long time, she refused to have any part of the conflict between Susan and David. Therefore, it was David against Susan, and despite David’s protests, Susan was eventually able to persuade the doctors to allow her to take Doris home with her again.

This arrangement, however, tragically only lasted about two months. Two days before Christmas, 1995, Susan dropped Doris off at the emergency room of Swedish Covenant Hospital and took off, apparently reunited with her estranged, alcoholic husband. From that point, David took control and arranged for Doris to be released to a nursing home.

Recently admitted, Doris seems to be adjusting well to her new surroundings, though she is confused much of the time and sometimes believes she is seeing various family members on television as she sits watching it. She is able to converse with other residents, though she seems to have a hard time focusing and has to concentrate to speak. She attends activities, but does not always participate unless helped by a staff member or a volunteer. David tries to visit as often as he can, but he is also burdened with having to manage the care of his grandmother, Gertrude, who is also still alive and in a different nursing home. Doris says that she would rather be home, but she understands that she cannot live alone. “It’s not so bad here,” she says, but she misses being with her family, especially her mother.

(Originally written January 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “More Like Sisters” appeared first on Michelle Cox.