Michelle Cox's Blog, page 23

March 27, 2019

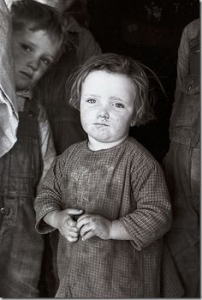

She Was Born “A Normal Little Girl”

Esther Matula was born in Chicago on August 13, 1929 to George Matula and Nicola Pacek, both of whom were children of Bohemian immigrants. George was born in Chicago and worked as a “heat treater” in a tool factory, and Nicola, who was born in Rice Lake, Wisconsin, cared for their four children: Vincent, Esther, Darlene and Herman. From time to time, Nicola helped out at the corner grocery store for extra money, but she was frequently so ill and in and out of the hospital so often that she didn’t make much.

Esther has always been considered to be “mentally retarded,” but Esther’s younger sister, Darlene, believes that Esther was actually born a “normal little girl.” As a young adult, Darlene spent a lot of time questioning various aunts and uncles and cousins and has concluded that Esther was not born “retarded” as everyone has always labeled her. Darlene discovered that one fateful day when her mother went out, she put George in charge of watching the children, which, at the time, was just Vincent and Esther, who was only a toddler. Apparently George got drunk, as usual, though he promised Nicola that he would not, and left the cellar door open. Esther wandered by and fell down the stairs, which is apparently when her “retardation” began.

The obvious person to ask the truth would of course have been Nicola, but she unfortunately died at the young age of 38. Always ill, Nicola’s doctor finally diagnosed her with a “poisonous, inward-growing goiter” and told her that she did not have long to live. Informed with this tragic information, Nicola knew she had to make a very difficult decision. She knew she could not leave Esther, who was just thirteen at the time, with George after she was gone, as, not only was George an alcoholic, but he was cruel to Esther as well, constantly teasing her and threatening to cut off all her hair, which never failed to throw Esther into hysterics. So before she died, Nicola packed up Esther and took her to a mental institution, where she felt she had no choice but to leave her, despite Esther’s screams to not be left behind.

Nicola returned home, utterly depressed, and was not long after again admitted to the hospital. She did not expect to ever go home again, but when she was surprisingly released, she made her way home and flew into a rage when she found George drunk again. Darlene remembers her mother yelling and screaming more than she ever had before, so much so that she collapsed and died right in front of them all of a cerebral hemorrhage.

On the day of Nicola’s funeral, Vincent, just seventeen, declared that he was joining the navy, that he wasn’t going to “get stuck washing dishes and caring for brats.” He left the very next day. Darlene was eleven, and Herman was ten.

Though Nicola had placed Esther at a Catholic facility in the city, the staff eventually transferred her to the mental asylum in Dixon, Il., where she lost contact with her family for many years. Darlene eventually married and moved to Arkansas, but she always felt guilty about leaving Esther behind in Illinois. Over the years, however, Darlene has been able to reconnect with Esther over the telephone. Supposedly, Esther recognized Darlene’s voice before Darlene could even explain who she was and was overjoyed to hear from her sister. After that, Darlene tried to get her brothers to call Esther as well, but both have refused, saying that Esther wouldn’t remember them anyway. Darlene has many times explained to them that, actually, Esther does in fact remember them and that she asks about them during every single phone call. Darlene has also told them that, amazingly, Esther remembers many family members and stories from way back. Still, Vincent and Herman have refused to call Esther even one time. Darlene suspects that they feel too guilty, especially when she told them what she found out from their aunts that Esther, despite her damaged mind, loved her siblings very much and that she had always been very protective of them until she was taken away.

When she reached her sixties, Esther was transferred to various nursing homes that could better care for her until she was finally placed in a facility called “Our Special Place,” which was a community house for seniors with mental disabilities. Esther apparently loved “Our Special Place,” the first “home” she had lived in since age thirteen. Esther stayed there for several years until she began having seizures and had to have brain surgery. Upon being released from the hospital, she was required to go back into a normal nursing home to recover, which has been very disorienting and upsetting to her.

Though Esther is officially under the care of a state-appointed guardian, Darlene has been kept informed. She is very distraught at the thought that Esther had to leave “Our Special Place,” and is trying to convince Esther’s guardian to let Esther go to Arkansas to be near her. Darlene hopes that Esther can come to live with her, but as Darlene is now legally blind and is also diabetic, this does not seem to be a realistic plan.

Meanwhile, Esther is not making a smooth transition. She is not able to communicate effectively with other residents and has no desire to participate in activities. Her only solace is listening to music. Darlene calls her every other day, but Esther finds it difficult to talk.

(Originally written: November 1996)

If you liked this story, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series:

The post She Was Born “A Normal Little Girl” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 21, 2019

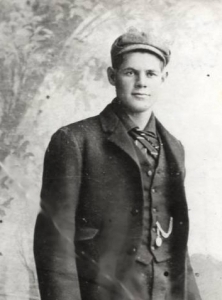

Waldemar Karlsson – 95 years young!

Waldemar “Wally” Karlsson was born on February 2, 1899 in Sweden to Ralf Karlsson and Beata Berglund. Ralf was a farmer, and Beata cared for their ten children: Olov, Njord, Melker, Carola, Ebba, Waldemar, Breta, Niklas, Ludvig and Hulda. As a young boy, Wally learned to play the violin and was often chosen to play in the church choir. When he was nine, he began a carpentry apprenticeship one day a week after school until he achieved full carpenter status at age fourteen. He left school then and began working on neighborhood farms as an extra hand doing odd jobs.

Waldemar “Wally” Karlsson was born on February 2, 1899 in Sweden to Ralf Karlsson and Beata Berglund. Ralf was a farmer, and Beata cared for their ten children: Olov, Njord, Melker, Carola, Ebba, Waldemar, Breta, Niklas, Ludvig and Hulda. As a young boy, Wally learned to play the violin and was often chosen to play in the church choir. When he was nine, he began a carpentry apprenticeship one day a week after school until he achieved full carpenter status at age fourteen. He left school then and began working on neighborhood farms as an extra hand doing odd jobs.

At one point, Wally was required to join the Swedish Calvary, but he only had to serve for nine months, as there were no wars going on at the time, he says. When he was nineteen, he became the manager of a very large farm that belonged to a sort of governor. After working for this man for only a year, however, Wally quit because he thought him very mean and greedy. Wally then went back to his father’s farm and asked to manage it. His father, deeply in debt, agreed to let Wally take over. Wally’s first decision was to cut and sell the lumber from the acres of woods on the farm, which quickly cleared the debt and made the farm successful.

Wally worked for his father until he was 27, at which time he decided to strike out on his own and left for America with his brother, Niklas. Their older sister, Carola, had already immigrated to Denver, while their brother, Olov, had gone to Chicago, where he lived with his wife, Norma, and their two daughters. Wally and Niklas made their way to Chicago and stayed with Olov and Norma during their first summer in America. Wally immediately found work as a carpenter, but Niklas went from job to job. After several months, Norma suggested that the two brothers get their own place, as cooking and cleaning up after the brothers, especially Niklas, was becoming too much work for her.

Wally liked and respected Norma very much, so when she gently suggested that they leave, he responded immediately, not wanting to upset her. He went out and found a nearby apartment for himself and Niklas, where they lived together for three years. Niklas, it seems, never really settled and made some very undesirable friends. He was constantly in trouble, and tensions rose between him and Wally. Finally, it became apparent that one of them would have to go, and since Niklas was wanted by some shady characters throughout the city, anyway, it was decided that he should be the one to leave—and not only the apartment, but the city as well. He made his way to Denver to live with Carola, where he reportedly created havoc there, as well.

Meanwhile, Wally continued working as a carpenter, doing odd jobs, until the Depression hit and he found himself unemployed and hungry. At one point he went for eleven days without eating because he was too proud to ask for food. Eventually a friend offered to try to get him a job as a dishwasher in a restaurant. Wally felt ashamed to have to rely on someone else to get a job, but in desperation he reluctantly went with him. At first the manager of the restaurant refused to hire him, saying that at age thirty-one, Wally was too old, but he later changed his mind. Glad of a chance, Wally worked extremely hard and impressed the owner so much that he offered Wally a job as the head maintenance man for his thirteen restaurants. Wally gladly accepted and worked for this man for over thirty years.

Wally had many sweethearts in Sweden and America, but he never married. He saw so many poor families over the years, he says, that he was determined not to have a family himself if he could not provide for them, and he always felt he could not. Instead, he traveled extensively with his boss, who was the master of a Masonic Lodge and who was very wealthy, and his family. Often, Wally went on vacation with them.

After working for thirty years for this man, however, Wally decided it was time to step down, as the responsibility for managing thirteen restaurants was getting to be too much. He then took a different maintenance job in the early 1960’s at an office building at Lincoln and Belmont, where he stayed for many years. After that, he became the maintenance man at the building he lived in in Logan Square until he was in his eighties.

Finally retired in earnest, Wally pottered around his apartment and still tried to do some carpentry work here and there. He loved listening to the news on the radio and reading the newspaper. His primary function, however, even into his nineties, was to run errands or go shopping for “the old boys”—men who were years younger than himself who lived in his apartment building. No matter how bitter or cold or hot it was, Wally never failed to go out and pick up items for “the old boys” and bring them back. He never locked his door and says he had no fear of walking the streets of his neighborhood at any time of the day or night.

Occasionally his niece, Ann Fogar, would telephone him from her home in Arlington Heights to check on her Uncle Wally, but, she says, he never once asked for help from her or her family. (Incidentally, Ann was one of Olov and Norma’s little girls whom Wally and Niklas lived with for a time when they first arrived from Sweden. Ann was just a baby at the time.) Ann says she has tried over the years to include her uncle in family gatherings, but he stubbornly refused to “bother them.” Recently, however, Wally’s neighbors telephoned Ann to report that Wally was very sick. Herself in a wheelchair now, Ann sent her two daughters to the city to check on him, where they found him feverish with what turned out to be pneumonia and delusional, as well. They telephoned an ambulance, and he was hospitalized for several weeks. From there he was discharged to a nursing home.

Wally seems to be making a relatively smooth transition to his new home, but he doesn’t see himself living here for very long, nor does he believe that he will ever be allowed to go back home. Instead, he expects to die very soon—”in a couple of weeks,” in fact—and plans to accelerate this by beginning to “breathe very slowly,” which he believes will facilitate his death. Despite this rather morbid plan, however, he has taken up playing the violin again and loves to seek out other residents with whom to have debates regarding politics or religion, or any topic, really. He is very knowledgeable and is an incredibly positive, cheerful, sweet man who seems much younger than his ninety-five years.

(Originally written: February 1994)

If you liked this story, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series:

The post Waldemar Karlsson – 95 years young! appeared first on Michelle Cox.

March 7, 2019

“Absolutely Full of Life”

Sara Arnold was born on January 27, 1900 to Vladan Medved and Terezia Novak in Zariecie, Slovakia. Vlad and Terezia immigrated to the United States in 1904 and settled in the Pilsen area of Chicago. Vlad found a job as a machine operator at Western Shade Co. and worked there until he died in 1925, whereupon, as a tribute to him, Western Shade shut down Vlad’s machine and draped it in a black cloth for one whole day, a testimony to his hard work and ingenuity. Terezia was left to care for their nine children: Vincent, Sara, Tomas, Stefan, Petra, Silvester, Rozalia, Olga, and Robert. Most of them were forced, then, to quit school to find work.

Sara Arnold was born on January 27, 1900 to Vladan Medved and Terezia Novak in Zariecie, Slovakia. Vlad and Terezia immigrated to the United States in 1904 and settled in the Pilsen area of Chicago. Vlad found a job as a machine operator at Western Shade Co. and worked there until he died in 1925, whereupon, as a tribute to him, Western Shade shut down Vlad’s machine and draped it in a black cloth for one whole day, a testimony to his hard work and ingenuity. Terezia was left to care for their nine children: Vincent, Sara, Tomas, Stefan, Petra, Silvester, Rozalia, Olga, and Robert. Most of them were forced, then, to quit school to find work.

Sara herself left school after finishing 8th grade and went live with a family friend, Mrs. Mickelson, where she got a job in the Loop at Western Union. Sara was a very independent, spirited young woman, involving herself in the temperance movement as well as the Red Cross during WWI. She wrapped bandages, sold war bonds door-to-door, and practiced marching in Grant Park with her fellow trainees in preparation for their planned trip to France to aid the soldiers there. The war ended, however, before they got a chance to go, and while they were overjoyed, of course, that the boys were coming home, there was a distinct feeling of disappointment that their adventure had been thwarted.

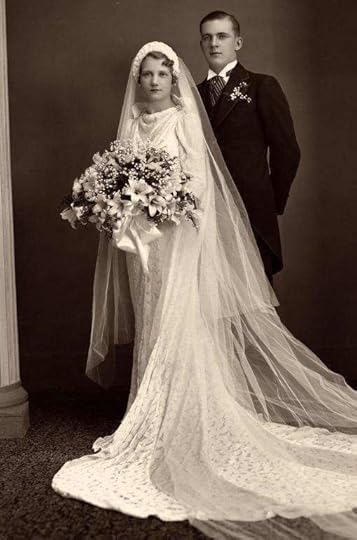

Not long after the war ended, Sara was walking home from work one day and passed down Jefferson Avenue where she saw a group of young men playing baseball in the street. One of them stopped playing and came over to talk with her. His name was William Laska, and he later became Sara’s husband on October 16, 1916. Sara was just 16 years old; William was twenty.

William worked as a truck driver with the Teamsters and did not approve of Sara working, so she stayed home and raised their four children: Susan, Rose, Evelyn and Martin. She also had twins, Peter and Paul, who died after only 6 hours of life. According to her children, Sara enjoyed her life as a housewife and cooked, baked and sewed everything from scratch. She even made her own beer, though she was very opposed to liquor! She was a woman, her children recount, who was “absolutely full of life.”

Every summer she and the children would pack up the car and traveled north of the city to the little village of Wauconda, where they had a summer cottage on the lake. Sara loved to fish, garden and read. She was a very intelligent woman and was very strong, and though she was in many accidents over the years, her children say that she never cried, complained or babied herself. They have many stories of Sara’s “misfortunes” over the years, including the time she was trapped in a burning car, the time she got her arm caught and mangled in a wringer, the time she stepped on a sickle and slashed her leg, the time she stepped on a rusty nail in Wauconda and drove herself to Chicago with a ballooned foot, the time she dug a fish hook out of her thumb, the time she split her finger open with an electrical saw, her various mild heart attacks, and the time she had her cancerous uterus removed. In all of these situations, her children say, Sara remained calm and cool. Her attitude is typified in a statement she made before her hysterectomy. “If it’s God’s will, I’ll make it; if it’s not, then I won’t!”

She was strong, too, when her husband, William, died in 1943 at age 47 of one of his “spells.” Afterwards, Sara lived alone with the children until 1950 when she married Augustus “Gus” Aronold, a radio and T.V. repairman, though they only had 8 years together before he died, too.

After Gus’s death, Sara lived alone in the apartment above her daughter, Susan. She sold real estate for a short time and also worked as a cashier in a department store for a year or two, but mostly she seemed to enjoy being at home. She and her friends formed the “Fat Ladies Club,” which consisted of them going to each other’s homes to eat and play Bunco. She was very handy and could repair many things around the house and loved to paint and wallpaper. She gardened and canned until age 80, as well as baked and cooked. When someone in the neighborhood died, Sara would bake hundreds of kolaches for the family. She was a very kind person, say her children, and she loved life, making it all the harder for them to place her in a nursing home at age 96 after she suffered a stroke. She is no longer able to speak, but her children speak for her, one of them always remaining by her side except to sleep at night, a beautiful testimony to a joyful life lived for others.

(Originally written: June 1996)

If you liked this story, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series:

The post “Absolutely Full of Life” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 27, 2019

Hated by Her Father Because of the Way She Looked

Zuza Gwozdek was born in Poland on March 16, 1909 to Przemo Dunajski and Wojciecha Jagoda, farmers just outside of Warsaw. Zuza was the third of eight children (Ula, Tosia, Zuza, Wanda, Olek, Miron, Stefania and Romana) and had the misfortune of looking almost exactly like Woujciecha’s mother, whom Przemo hated. By the time Zuza was three, Przemo could not stand the sight of her and, having other hungry mouths to feed anyway, sent Zuza away to a Catholic orphanage in Warsaw.

Zuza Gwozdek was born in Poland on March 16, 1909 to Przemo Dunajski and Wojciecha Jagoda, farmers just outside of Warsaw. Zuza was the third of eight children (Ula, Tosia, Zuza, Wanda, Olek, Miron, Stefania and Romana) and had the misfortune of looking almost exactly like Woujciecha’s mother, whom Przemo hated. By the time Zuza was three, Przemo could not stand the sight of her and, having other hungry mouths to feed anyway, sent Zuza away to a Catholic orphanage in Warsaw.

At the orphanage, Zuza received a sketchy education at best and was instead expected to work. When she finally turned eighteen in 1926, she was allowed to leave and “start my life,” as she puts it. Not knowing what to do, however, she decided to travel to another city where she had a friend, Renata, who had been in the orphanage with her. Renata welcomed Zuza with open arms and allowed her to stay with her. Not long after she moved in, however, their apartment was broken into while the girls were out for a walk, and all of Zuza’s few possessions were stolen. The robbery hit Zuza very hard, and she became depressed and withdrawn. Renata, in an attempt to cheer her up, decided to have a party and invited some friends over. It was then that Zuza was introduced to a young man by the name of Ludwik Gwozdek, who seemed very attracted to her.

Despite the party and the possibility of a romance, Zuza remained depressed. In fact, one day she found herself on a bridge overlooking the river near Renata’s flat. She contemplated jumping, but a voice told her “Don’t jump. Your life will be okay.” For Zuza it was a profound moment and the beginning of what she describes as her spiritual life. She felt overwhelmed that someone above was watching over her, that someone actually cared for her for the first time in her life. Zuza climbed down off the ledge and married Ludwik shortly thereafter.

The young couple at first lived with Ludwik’s family and tried to find work where they could, but the marriage, even then, was not a smooth one. When the war began and Germany invaded Poland, Zuza and Ludwik were separated and sent to different work camps. Zuza was forced to work in a factory until the war’s end.

In 1945, Zuza was released from the work camp. Both Renata and Ludwik were gone, as was his family, and Zuza didn’t know what to do. Alone and very ill, she decided to walk all the way back to her parents’ farm, hoping that they might still be there. Zuza was overjoyed to find that at least her parents were still alive, but she did not receive the happy welcome she had hoped for. Her father told her that she could stay at the farm if she could pay for her upkeep. The only thing she had of any value was a beautiful babushka, which she handed over to him to be sold. Her father, however, rather than selling it for money, instead gave the babushka to her sister, Tosia, as a gift.

Heartbroken yet again, Zuza left the farm and sought refuge from some neighbors. They allowed her to stay for a short time and then suggested she go to Warsaw and try to find work there. They gave her extra food and clothes and some cigarettes to sell to help get her started. Zuza eventually made it back to Warsaw and, through a strange turn of events, was reunited with her husband, Ludwik. At first Zuza was happy that he was still alive, but she soon began to regret it. Ludwik had changed during the war. He had once been loving and kind, but he was now short-tempered and even brutal. He frequently beat Zuza and “abused” her in other ways. He seemed unable to hold a job for any length of time, forcing the couple to move from city to city constantly, looking for work, towing their first child, Karol, along behind them. After thirteen years of this, they eventually settled down in Dansk and had another child, Ada. Zuza saved and saved until she had enough money to buy a sewing machine so that she could make extra money. She would also walk every morning to the countryside, buy cheap fruit and vegetables and then walk back and sell them in the city for a small profit.

Meanwhile, her marriage with Ludwik grew worse, and he became even more violent. One night, the fighting was so bad that the neighbors called the police. This incident, plus the fact that Karol and Ada were always nervous and fearful, pushed Zuza into leaving Ludwik. At first she was afraid that he would come after them, but he did not. At this point, Zuza had a growing reputation as a skilled seamstress. So between her work as a seamstress and working at the local orphanage, which was very dear to her heart given her own childhood, she was able to scrap out a meager existence.

Karol eventually married a woman named Maria and had a child, Leo, with her. Not long after Leo was born, Karol immigrated to America. He worked there for eight years to save up enough to send for Maria and Leo, as well as Zuza and Ada. For a while they all lived together in an apartment in Chicago, but Karol and Maria started to have marital problems. Karol decided to move his little family to Texas for a fresh start, but Ada and Zuza remained in Chicago, where Zuza found work as a seamstress in a factory to support Ada and to put her through high school.

Ada eventually married, too, but moved to the south side to be near her husband’s family. Zuza lived alone for many years, then, until she eventually retired at age seventy. When she announced that she was quitting, her boss threw her a little party and reportedly told everyone that he was going to have to hire two people to replace her. Zuza is very proud of this and frequently repeats it. Even in retirement, Zuza continued to sew, often making clothes for her grandchildren. Her favorite thing to do was to watch TV and movies to observe the clothes the actors wore and would then try to imagine how she would go about making them.

Zuza has been living independently until this past year when she began to fall repeatedly. Karol has been very worried about her, but he is preoccupied with Maria’s recent diagnosis of cancer and impending death. Ada has been worried, too, and for a short time had Zuza come and live with her. Recently, though, Ada has been having a difficult time accepting her role as caretaker for her mother, as she has spent the last fourteen years caring for her father-in-law, who recently passed away. Ada feels tremendous guilt, but isn’t sure she is emotionally capable of starting all over again as being the primary caregiver for another elderly person. Eventually, then, with heavy hearts, it was decided between her and Karol that Zuza should go to a nursing home.

Zuza is very alert and aware and able to carry on a conversation. She seems to be making a relatively smooth transition. She enjoys the Polish food and music and talking to other residents, though she sometimes has bouts of melancholia. It is fitting, she says, that she has to start all over yet again. She feels that she has never really fit in anywhere and has spent most of her life moving. “I’ve lived among strangers all my life,” she says. “This isn’t so different.”

(Originally written: July 1996)

If you liked this story, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series:

The post Hated by Her Father Because of the Way She Looked appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 21, 2019

From Professor of Physics to Janitor

Sasha Pasternak was born on March 12, 1946 in the Ukraine. His parents were Martyn Pasternak and Alberta Jelen. Jelen, Sasha reports, means “stag” in Polish, and he seems very proud of his mother’s name.

Sasha Pasternak was born on March 12, 1946 in the Ukraine. His parents were Martyn Pasternak and Alberta Jelen. Jelen, Sasha reports, means “stag” in Polish, and he seems very proud of his mother’s name.

Martyn was a Ukrainian Jew, and Alberta was a Polish nurse living in the Ukraine with an elderly woman she was hired to care for. As it happened, the elderly woman’s children and grandchildren often came to see her, and one day one of her grandson’s brought a friend along by the name of Martyn Pasternak. As soon as Martyn saw Alberta, he fell in love with her, and they married in 1928. Martyn worked as an economist, and Alberta continued working as a nurse until their first child, Anna, was born in 1932.

Fourteen years later, in 1946, a son was born – Sasha. Sasha attended high school and university, eventually becoming a professor of physics, with a specialty in medical radiation. He was on the chief of staff in this field, did extensive research and gave lectures at the university in the evenings and enjoyed his career immensely.

In 1969, when he was 23, he married the love of his life, Liliya. He had been dating a different girl, Vira, shortly before this and the two had gone to a friend’s apartment one night to celebrate Vira’s birthday. At the impromptu party, Sasha was introduced to his friend’s date, Liliya, and instantly fell in love with her, perhaps in the same way his father, Martyn, had fallen in love with Alberta. Ten days after Vira’s birthday party, Sasha married Liliya in a quiet service.

Sasha and Liliya, who worked as a language teacher, made a happy life for themselves in the Ukraine and had two sons: Ivan and Denys. Sasha says he left the Communists to themselves and lived his own life. He felt he had a pretty good salary, a great job, a nice family and a nice apartment. When the Communists fell, however, his life began to fall apart. His salary shrank to almost nothing and his sons, just leaving university, had no job prospects. Seeing the situation in the Ukraine as hopeless, Sasha decided to move the family to America and arrived in Chicago in 1994 with Ivan and his wife and daughter; Denys; and Liliya’s parents. And while there proved to be much more opportunity for their sons, Sasha and Liliya’s prospects worsened. Sasha gave up his brilliant career in research to become a janitor, and Liliya found a job at the counter of Lord and Taylor.

After about a year in America, the powers that be at Evanston Hospital where Sasha worked as a janitor heard of his background in the Ukraine and offered to send him through 14 months of training in medical radiation in exchange for him to continue working as a janitor as a volunteer. Sasha desperately wanted to take the offer, but eventually declined it, knowing that they could not exist for that period of time without his salary. For one thing, shortly after their arrival in America, Liliya’s parents began to have a myriad of health problems. Her father had to have a lung operation and his leg amputated, which required extensive hospitalization. In order to visit him every day, Liliya’s mother had to take three buses to get to the hospital, and eventually the stress got to her. She had a heart attack and then a series of strokes and falls before she finally died.

Sasha eventually was offered a more humble position of lab technician. It did bring in a little more money than he had been making as a janitor, but the family still struggled because Liliya had been forced to quit her job to take care of her parents when they were ill and dying. As luck would have it, things got even worse for the Pasternak’s. In October of 1996, just as Liliya was getting over the death of her father, Sasha was hit by a car. He spent eighteen days in the hospital before he was transferred to a nursing home to more fully recover. Upon his admission, he had a lot of anxiety and found it difficult to lie in bed all day. He has since begun to be up and about more and looks forward to Liliya and his sons coming to visit each day. He is eager to get home and back to work, he frequently repeats, though he worries that his job will be given to someone else. His boss, he says, has promised to hold his job, but, Sasha says, “I am a pessimist at heart. I wait and see.”

(Originally written: October 1996)

If you liked this story, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series:

The post From Professor of Physics to Janitor appeared first on Michelle Cox.

February 7, 2019

He Promised to Take Her Dancing Every Week!

Clara Mae Hansen was born on May 14, 1902 in Adrian, Michigan to Henry Engelskirchen and Katherine Burkhart. Henry was of German descent but was born in Mendota, Illinois, and Katherine was originally from Orland, Il. Henry apparently had a hard life. When he was ten years old, his stepmother made him quit school to go work in a brickyard. Eventually, he ended up working as a superintendent in a piano factory in Mendota. He met and married Katherine Burkhart, and together they had nine children: Arthur, Henry, Walter (who died at eleven months), Harvey, Clara, Alma, Willard, Howard and Florence.

When the piano factory closed down in Mendota, the family moved to Steger, Illinois, where there was another piano factory. They remained there only five years, however, as they did not like Steger and decided to try their luck in Chicago. Clara was nine when they moved to the big city.

They settled in the northwest part of the city and managed to make a living as best they could. Tragically, however, Katherine died in August of 1916, just five years after moving there. According to Clara, the family was attending the funeral of a friend on the outskirts of the city, and as they walked along in the funeral procession in the hot August sun, Katherine became overwhelmed with thirst. They happened to pass an old, deserted farmhouse near the cemetery, and when Katherine spotted a well in the front yard of the farmhouse, she broke off from the procession to get a drink from it. Alarmed, Henry tried to stop her, warning her about drinking from a well that had not been used for such a long period of time. Katherine ignored him, however, and drank from it anyway. As a result, she came down with typhoid and eventually died.

At the time of her mother’s death, Clara was fourteen and as the oldest girl was made to stay home and keep house and care for the children. Her youngest sibling, Florence, was only four. Clara, who had been so looking forward to going to high school, had to quit after only attending for two days. She was utterly crushed, as it had been her dream to go to school beyond eighth grade. She begged her father to hire someone to come in and take care of things instead of her, but he claimed he couldn’t find anyone who would take on such a big family and that he couldn’t afford it anyway.

So Clara stayed home for two years, and when she was sixteen, Henry was finally able to find someone to hire on a part-time basis. By then, however, it was too late for Clara to attend high school, so she got a job at Carson’s Wholesale, which she ended up really enjoying. There, she met a friend, Florence, who was always begging her to come with her on a Saturday or a Sunday night to the nearby Mable Theatre on Elston and Irving Park Road (later becoming the Revue Theatre in 1934), which, Florence claimed, had the best vaudeville acts around. After much refusing, Clara finally agreed to go with her one night and found herself laughing as much as Florence. They spent the walk home talking about which had been their favorite acts and laughing all over again. Eventually, however, they noticed that two young men were following behind them. When the girls finally reached Clara’s house, one of the boys, Arthur Phillip Hansen, asked if he could have Clara’s telephone number. Clara lied and said they didn’t have a telephone, but Florence spoke up and said that “they did so have a telephone!” and promptly gave Clara’s number to the hopeful Arthur.

It turns out that Clara rather liked Arthur, and they dated for two years before Arthur worked up the courage to propose. Clara was hesitant to accept him because she didn’t want to give up going to dances. Although she liked Arthur well enough, her real love in life was dancing. Arthur, for his part, didn’t dance, but he swore to her that if she married him he would drive her and her girlfriends to the dance halls every week. Clara agreed, then, and was married at eighteen, which she later said, “was too young!” and that it was “a rotten trick!” as no sooner was she married but she got pregnant, and that was the natural end of her dancing days.

Arthur and Clara seemed happy enough, however, and had three sons: Robert, Richard and Jack. They lived in the same apartment on Kasson Avenue for 29 years. When they first met, Arthur had a job as a roofer, but after three close calls, he took up carpentry instead and worked at that for the rest of his working life. Clara’s father, Henry, died at age 71 the night Pearl Harbor was bombed. Clara does not remember of what. Arthur died in 1990 at age 93 at home, with Clara by his side.

Since Arthur’s death, Clara has steadily gotten worse on her feet and has fallen several times. All three sons are themselves retired and battling health problems and are therefore unable to care for Clara. Since the time that Arthur died, they have been suggesting that she go into a nursing home, but she has continually refused. Recently, however, they were able to get her to go to a nursing home on “a trial basis” is what they told her. Clara therefore believes that she will soon be returning home, though her sons confess that this is probably not a realistic option. Clara, despite wanting to go home, is making friends and participates in many of the offered activities. “All of my friends have died,” she says and enjoys smoking and meeting other residents. Her mind is still extremely sharp, and she can remember many stories of the past. She likes the facility very much, she says, but she is just “biding my time” until she can go home.

(Originally written: December 1993)

If you enjoyed this story, read Michelle’s historical mystery series:

The post He Promised to Take Her Dancing Every Week! appeared first on Michelle Cox.

January 31, 2019

The Unstoppable Boris Jankovic

Boris Jankovic was born on June 24, 1906 in Chicago to Andrej Jankovic and Dora Babic, both immigrants from Yugoslavia, though they grew up on neighboring farms in Ohio. When she was seventeen, Dora married a man by the name William Utzmann and had a baby boy, Adam, with him the following year. When Adam was just a year old, however, William was killed in a farm accident. Dora then turned to her childhood friend, Andrej, and they soon became engaged to be married.

Andrej worked on his father’s farm and also as a hired hand, and Dora stayed at home to care for Adam and four more children that came along: Boris, Natalia, Dusan, and Jasna. At some point, however, Andrej and Dora made the decision to move to Chicago to try to make a better living. Andrej found work as a janitor at a college, and Dora began cleaning offices at night.

Boris went through eighth grade in Ohio, and when the family moved to Chicago, he got a job at a furniture store loading trucks. He saved every penny, and after eight years, he had enough to buy a little fruit and vegetable market on Division. His little venture became relatively successful, and even his father, Andrej, sometimes worked for him.

When Boris was twenty-eight, he became acquainted with one of his regular customers, a young woman by the name of Nancy Horvat, who came to the market almost daily, as she was one of twelve siblings and they went through groceries very quickly. Boris began to look forward to Nancy coming in each day and finally worked up the courage to ask her out. Nancy, who was very shy, at first said no. Boris persisted, however, and finally persuaded her to go to see a movie with him. The two of them hit it off right away, and she and Boris began dating. Eventually, Boris proposed to her, but Nancy turned him down, saying that she needed to stay home and care for her mother who was blind and partially paralyzed and her chronically ill sister as well.

Boris considered the situation and decided to proceed anyway. He was quite smitten with Nancy and wanted her to be his wife. His solution was for him to move in with Nancy’s family so that Nancy could still take care of her mother and sister. Nancy’s father had already passed away and most of her siblings had already moved out, so it was a solution that satisfied everyone. Boris continued working ceaselessly at the market, and Nancy stayed home to care for the invalids and eventually their two little girls, Karen and Francine.

Twenty years passed, and eventually Nancy’s sister and mother both died, and the girls married and moved out. Boris decided he needed a change as well and sold his market in 1952 to a friend. He wanted to get into the emerging food industry and therefore took a job working at “a drive-in burger joint” while he went to school at night to learn bartending.

Two years later, he put his experience and schooling to use when he bought the Lisle Lounge in Lisle, Illinois in partnership with his sister, Natalia, and her husband, Len. Boris and Len worked the bar, and Natalia and Nancy ran the kitchen. Boris and Nancy sold their house in the city and moved to Lisle to be closer to the restaurant. The Lisle Lounge was apparently a big success. As he had at the market, Boris worked ceaselessly and had little time for hobbies except a bit of gardening and listening to music. Occasionally, he and Nancy would go dancing, which they both enjoyed. Boris loved working at the restaurant, and it soon developed a faithful crowd. Boris had dreams of expanding it, but his partner, Len, was against it. What began as a discussion eventually evolved into arguments and then finally, a huge fight. Unable to come to an agreement about the restaurant’s future, they decided sadly to sell it. Boris tried to buy out Natalia and Len’s share, but he couldn’t come up with the needed money, and Len wouldn’t budge.

After they sold the Lisle Lounge, Boris got a job as a bartender at a new restaurant in Naperville called the Willoway Manor. He very much enjoyed working there, as he bartended at night and did the restaurant’s yard work during the day. Eventually, it closed, however, so he then got a job bartending at Sharko’s in Lisle. He remained there until he was seventy-two when he finally retired.

At that point, Boris and Nancy decided to travel. They went to Europe and twice to New Zealand. They also made several trips to Arizona to visit their daughter, Karen, and her family, and to Hawaii, where their daughter, Francine, was living.

Sadly, in 1986, Nancy was diagnosed with ovarian cancer and died within a month. It was a terrible blow to Boris, who could barely remember life without her. She had been his best friend. He began drinking heavily, and his own health began to decline. Francine and Karen both agreed that something needed to be done, but they disagreed as to what. Francine was of the opinion that Boris should go to a nursing home, but Karen was adamant that he would never survive in such a place. Ultimately, Karen won out and flew to Chicago to bring her father back to Arizona to live with her.

Unfortunately, two years after her mother died, Karen’s husband was also diagnosed with cancer, and she found it almost impossible to care for both him and Boris. Boris, it seems, did not particularly like Arizona, anyway, and wanted to go back to Chicago. Reluctantly, then, Karen made the arrangements for him to be admitted to the Golden Age Retirement home in Lyons, Illinois.

Boris apparently really enjoyed the Golden Age and made a smooth transition to life there. Initially, he joined many activities and made several friends. After six months, however, he became particularly close with a woman named Ida Kovacevic. Ida soon became his constant companion, which, at first, Boris enjoyed. She became very possessive of him, though, as time went on, and isolated him from other people as much as she could. The staff tried to intervene, but they were not completely successful in getting Boris to branch out. Boris stopped going to activities and social gatherings to spend all of his time with Ida, and his budding new friendships with other residents died off. This went on for about two or three years, so when Ida suddenly passed away, Boris was left with very few social supports and grew extremely depressed. For a time, he refused to join any activities, and his appetite was seriously affected.

Right at that time, the ownership of the Golden Age changed hands, and the new owners decided to make it a more independent living facility and made arrangements to transfer all residents who needed assistance to other facilities. Boris unfortunately fell into this category. For awhile, several members of the staff, who really loved Boris and wanted him to stay, tried “covering” for him as much as they could, but it soon became obvious that Boris could not exist independently.

Thus, Karen was again contacted, and the decision was made to transfer Boris to the Bohemian Home for the Aged in the city, where it is hoped he will make a smooth transition and that he will enjoy being in a Slavic environment. So far, Boris is happy that he is served a pilsner every night with his dinner and enjoys hearing old Bohemian songs, some of which he is familiar with from his childhood. He is a very sweet man and seems eager to start all over yet again.

(Originally written: February 1995)

If you liked this story, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series:

The post The Unstoppable Boris Jankovic appeared first on Michelle Cox.

January 3, 2019

“So Damned Mediocre!”

Leona Wilson was born in Oklahoma on December 16, 1906 to Nigel Wilson and Elizabeth D’Evers. Nigel was born in England and had a passion for the American Wild West since the time he was a little boy. So strong was his desire to be a cowboy that he ran away from home as a teenager and got a job on a ranch in Colorado. His father eventually tracked him down and made him return to England to finish his education, promising that once he did so, he would be free to do as he liked.

Leona Wilson was born in Oklahoma on December 16, 1906 to Nigel Wilson and Elizabeth D’Evers. Nigel was born in England and had a passion for the American Wild West since the time he was a little boy. So strong was his desire to be a cowboy that he ran away from home as a teenager and got a job on a ranch in Colorado. His father eventually tracked him down and made him return to England to finish his education, promising that once he did so, he would be free to do as he liked.

Nigel accordingly graduated from university with a degree in business and immediately returned to America. He first went to Chicago, where he met a young woman, Elizabeth D’Evers, at the Presbyterian Church he was attending. The two of them began dating while Nigel worked in an accounting firm to earn money to go back out west. Eventually, Nigel and Elizabeth married and had two children, Edmund and Gerald, before they had finally saved enough money to buy a ranch in Oklahoma.

Once settled in Oklahoma, the Wilsons had three more children: Margaret, Leona and Catherine. Leona says that Margaret was her “mother’s pet” and could do no wrong. She was very spoiled, and, consequently, Leona hated her. The Wilson’s remained on the ranch for about ten years before Nigel decided he had had enough. Somehow, ranch life was harder than he had remembered it being as a boy. The family moved again, this time to Denver, where another baby, Herbert, was born. Leona says that she hated Herbert more than she hated Margaret, as he was “a terrible brat and annoyed everyone.”

Leona reports that she had a tolerably good childhood. Her family, she says, wasn’t terrible; their great sin was that they were “so damned mediocre.” She carries a bit of a chip on her shoulder, however, as she feels like she was pretty much ignored and even cheated by her parents. Margaret and Herbert, she says, got everything they wanted, while “I was given nothing,” she says.

Leona remembers begging her parents for violin lessons, for example, but they refused to waste money on such a thing. Later, she begged for art lessons, but they again “ignored me and never encouraged me at all!”

After Leona finished elementary school, Nigel and Elizabeth decided to divorce. Leona is not sure why, but she thinks it might have been because Elizabeth wanted to move back to “civilization.” Thus Elizabeth took the three girls and Herbert and returned to Chicago, while Nigel and the two oldest boys remained in Colorado.

Elizabeth and the children moved in with her parents, the D’Evers, and Leona started high school. She eventually graduated and then begged to be allowed to attend the Art Institute, but Elizabeth and her well-to-do parents refused to throw money away at such “utter nonsense.” Leona wrote to her father, asking him to pay for her education, but he also refused.

Deeply resentful, Leona got a job and put herself through school. When she finally graduated with an art degree from the Art Institute, she only had enough money to rent a little studio, where she worked and also began giving art classes. She didn’t have enough money to move out of her grandparents’ house, though, and thus had no choice but to remain there, even though she had grown to seriously dislike them over the years for their “snobbish superficiality. They thought they were something because they had a ‘D’ in front of their name,” she says. “To me, it stood for ‘dumb.’ They thought they were so aristocratic, and it was ridiculous that they only respected people who had more money than them.”

Leona tried her best to ignore her family and their disparaging comments and threw herself into teaching. “It is the greatest fun to teach children,” she says, “because you don’t teach them, they teach you!” After a year of teaching, however, Leona decided to go to New York for a weekend to get away from her mother and grandparents and to also see art museums and galleries. In just a couple of days, she fell in love with New York and returned to Chicago with the intention of packing up and moving there.

She was in the process of going around to different galleries and studios where her friends were to say goodbye, when she happened to meet a new artist, a man by the name of Sherman Abrams. Leona was immediately drawn to Sherman and his work and began following him all around town. She says that she fell in love with him instantly and describes it as “Pow!” Sherman, apparently aware of Leona’s feelings for him, initially tried to avoid her, as he mistakenly thought she was only fifteen. Leona kept finding him, however, and repeatedly invited him to her studio to see her work. Each time he would agree to come but then not show up. Still Leona persevered.

Frustrated by Leona following him, Sherman eventually asked a mutal friend how old she was. The friend said that he thought Leona was in her twenties. Surprised, Sherman finally went to her studio, burst through the door and said “Just how old are you?” When she told him she was twenty-two, he immediately asked her out on a date.

Sherman and Leona eventually married and had two children: Pamela and Rose. Sherman became a very successful commercial artist, and he and Leona were very happy for a time. Sherman’s brothers all loved Leona, apparently, but his mother did not. She resented the fact that Leona wasn’t Jewish, and tried to “make our life miserable,” Leona says. Eventually, the pressure became too much, and the two of them decided to divorce. Leona says that she “grew beyond him.” He was very “juvenile and childish, and his mother wanted him to stay that way.”

After the divorce, Leona packed up Pamela and Rose and moved to New Orleans, where she happily joined the artist community there. She enrolled the girls in a “very good public school in the French Quarter” that emphasized art. Meanwhile, Leona painted, exhibited and taught in various schools. She feels that she was very successful as an artist and as a parent. She is extremely proud of the fact that she devoted so much time to taking her children to see art exhibits, plays, museums and galleries while other women “were at home exchanging housework stories.” She devoted her life to her art and her children and encouraged them to explore any artistic avenue they desired.

As it turned out, upon her graduation from high school, Pamela decided she also wanted to attend the Art Institute. Leona was thrilled with this decision and saw “a lot of promise” in Pamela’s work. Accordingly, she moved them all back to Chicago and contacted Sherman about helping to pay for Pamela’s tuition. She was dismayed when he refused to “give me one cent!” Leona could not believe that Sherman, himself a successful commercial artist, would not encourage his daughter to study art and concluded that perhaps he was jealous of Pamela’s skill. Even now, Leona still seems fixated on this episode in her life, even after so many years have passed. She repeats this story over and over until redirected.

Leona was determined that Pamela should go to the Art Institute, however, and took on two jobs to make the money to pay for it. “I worked night and day,” she says proudly. Similarly, when Rose graduated from high school, she expressed a desire to attend Hunter College in New York to pursue writing. Again, Leona worked two jobs to put Rose through. When both girls were finally finished college, Leona returned to New Orleans to pursue painting and also took up sewing.

Leona remained in New Orleans, living independently, until just about four years ago when she began having difficulty with her health. Pamela suggested that she move back to Chicago. Leona agreed and moved in with Pamela, at Pamela’s invitation, and continued to paint a bit. Not long after the move, however, Leona’s health began to seriously worsen. She had a stroke and also went legally blind. Added to that, she has recently been diagnosed with the beginnings of dementia. She was hospitalized for several weeks after her stroke, and upon her release, the hospital discharge staff recommended nursing home placement.

Leona is very upset about her new living arrangement and has a lot of anger toward Pamela, whom she says “dumped her here.” In turn, Pamela is very sharp toward her mother when she visits, which consist of five- to fifteen-minute intervals. In her more rational moments, Leona says that she understands that it would be impossible to still live with Pamela, but she seems to quickly forget this and grows angry all over again, saying that she paid for half of Pamela’s house and that she should be allowed to live there. At other times Leona is calm and pleasant and attempts to socialize with the other residents. It is hard to participate in activities, though, because of her blindness. She says that she can see light and dark, but no color. “Can you imagine that?” she asks. “What living in a colorless world is like to an artist?” Over all, she seems to be trying to make the best of her situation, but, she says, “I feel empty inside.”

(Originally written: July 1996)

If you liked this story, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series:

The post “So Damned Mediocre!” appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 27, 2018

A Girl Like Addie

Liberty Adelaide Appleby was born in Chicago to Alice Myers and Maurice Von Pfersfeld on July 4, 1914. Because she was born on Independence Day, Maurice insisted they name their new daughter Liberty, though Alice had wanted to call her Adelaide. They settled for Liberty Adelaide, but she was always called Addie.

Addie does not remember much about her mother’s family, except that they were of German descent. Her father’s family, she says, immigrated from Alsace-Lorraine. Maurice apparently loved tell the story of how the Von Pfersfeld’s were once barons back in the “old country” and how his grandfather, one Archibald Von Pfersfeld, eloped with a penniless woman and immigrated to America. They made their way to Chicago and to Logan’s square in particular, where they had three sons, one of them being Johann, who was Maurice’s father.

Maurice grew up in Logan’s square and got a job as a delivery truck driver for the Olsen Rug Company. He met Alice Myers at a church picnic, and after a short courtship, they married. They eventually got their own apartment on Campbell, where they raised their two children: Addie and Marie, who were six years apart.

Addie graduated from elementary school and had begun to attend high school when the stock market crashed, throwing the country into the Great Depression. Maurice, like thousands of others, lost his job. Without Maurice’s paycheck, the family was thrown into poverty, as they had little savings. They didn’t feel poor, however, Addie says, because everyone else was “in the same boat.”

At some point, the government began giving out food at the local Armory, which the Von Pfersfeld’s had no choice but to accept. Alice, being a proud woman, could not quite bring herself to go down and stand in line, so she sent Addie to go for her. “It was good food,” Addie says, “but it got boring, so we traded with people in the neighborhood.” Addie says that the Depression was a terrible time during which a lot of people suffered, but, on the other hand, she says, it was a time of great camaraderie among neighbors, the likes of which she never witnessed again, even during the war. “People looked out for each other back then.”

Addie quit school and began looking for a job, which turned out to be easier to get than it was for her father. Addie attributes this to her good-looks. “I had a man-stopping body back then,” she says, “and a personality to go it!” Jobs were therefore never hard for her to come by. It was keeping the job that was the problem, as she was forever getting fired for slapping an owner or a manager for “feeling me up” or trying to trap her in a back room. “I wasn’t that kind of girl!” she says. Addie claims to have had so many jobs, often working two or three at a time over the course of her 53-year working career, that she can’t remember them all.

One of her favorites, though, was working at the Chicago World’s Fair, first at an ice cream booth and then as a “Dutch Girl” for a Dutch Rubber Company. Addie says that this was her favorite job because all she had to do is dress up in a Dutch Girl costume and pass out flyers all day. “It was a great job,” Addie says, “because it was easy, and I got to see the whole fair on my lunch break.”

Over the years, Addie had dozens and dozens of waitress jobs. She also worked as a dishwasher, a maid, a floor-scrubber, a counter girl/hair curler demonstrator at Marshall Field, and even as a solderer at a radio factory, which, she says, was terribly boring but paid well. When these more mundane jobs petered out, Addie was obliged to venture into more risqué territory, for which she was easily hired because of her extreme beauty.

Some of these more risqué jobs included working as a “bookie’s girl,” which meant she collected coats and was supposed to serve as many drinks as possible to the “clients.” She also worked as a “26 Girl,” which was a dice game popular in Chicago bars. It was her job to collect money, keep score and encourage men to order drinks, for which she received a percentage of the house’s profits. After that, she took a job as a “taxi dancer” at a local dance hall, where, she says, “I was paid to stand around and look pretty.”

Taxi dancers apparently originated as dance instructors. They were hired by dance halls to instruct men in how to dance. For ten cents, a man could dance with a pretty girl for one dance, thus earning the girls the nickname of “dime-a-dance girls.” Addie says that there really were some shy, quiet boys who actually came in with the intention of learning to dance, but most of the men that came in were there to “feel the girls up.” It was infuriating, Addie says, because the dance hall owners claimed that there was a “no touching” policy, but they not only looked the other way, but actually encouraged men to “have their way.”

This, plus the fact that she would not get off until two or even sometimes four a.m., caused her to finally quit this job, despite the fact that she had a little gang of neighborhood boys who looked after her. These boys knew Addie to be “a good girl,” and out of worry for her would wait at the el stop each night and follow her, at a discreet distance, until she made it safely home.

From taxi dancing Addie went to being an usherette at a burlesque theater, which made taxi dancing seem like “a kid’s birthday party,” she says. Desperate for money, she saw an ad in the paper when she was nineteen for usherettes at a burlesque house downtown on Monroe. She went to apply and was shocked to find that hundreds of women were lined up around the block, hoping for one of the fourteen available positions.

Addie almost gave up hope then and there, but decided to join the line and take her chances. Once inside, a line of girls were called up on stage and had to show their legs and then lift their skirts to show their buttocks. The men in the seats who were directing these dubious “auditions,” then went down the line, pointed at each girl and either said “left” or “right,” indicating which door they should go through, off stage. The door to the left led to the alley, and the door to the right led to a little side room. Eventually, all the girls in the side room had to line up on stage once more, and this time, the men went down the line, saying “you, you, you, etc.” until they had chosen fourteen girls.

Addie was one of the chosen. She was given a beautiful costume and briefly trained in the art of ushering. The girls were closely chaperoned and a very strict policy of no touching or “hanky-panky” between the customers and the girls was enforced. In fact, there were two male “ushers” who were really there to act as bouncers if any man in the crowd got out of line with the girls. The girls were also required to go to the restroom in pairs for safety’s sake, though, Addie recalls, this policy once backfired for her.

Addie tells the story of how one night, not long after she started, she and a partner went to the restroom as per the policy, but not long after entering the bathroom, another of the usherettes, a girl by the name of Mimi, grabbed her from behind and started kissing her neck. Addie loudly protested and pulled away. Mimi quickly apologized, saying that she had obviously made a mistake. Most of the usherettes, and even the dancers, she told Addie, were actually lesbians. Despite this incident, Mimi eventually became Addie’s best friend and invited her after the shows to her “lesbian parties,” as Addie called them, though none of the girls ever made an advance on Addie again. Mimi became her protector and would often attempt to shield the “innocent” Addie’s eyes from some of the girls “making out” in dark corners.

At some point in time, Addie, who claims to have had “hundreds” of marriage proposals in her lifetime, accepted the hand of one Bill Zielinski and had a child, Hattie, with him. It was a very brief marriage, however, and they divorced when Hattie was only one year old. Addie does not like to talk about Bill or about this time in her life and offers very few details. If asked about it, she will swiftly change the subject.

Apparently, when Hattie was still very little, Addie again married, this time to a man named Arthur Appleby. Arthur was an insurance salesman, and after marrying him, Addie, for the first time in her “adult” life, did not have a job, but instead stayed home to be a housewife and to care for Hattie. Not very long into their marriage, however, Arthur developed Parkinson’s disease and became an invalid, forcing Addie to go back to work. At times she was able to get Hattie, who had inherited her good looks, modeling jobs at Marshall Fields, which helped pay some of the bills.

Addie herself was loathe to go back to any risqué jobs, now that she was a wife and a mother, and tried to find something more respectable. A friend of hers had a job as a private secretary and Besley Wells Tool and Dye and told Addie that there was an opening there as a bookkeeper. Addie knew nothing about bookkeeping, so she went to the local high school, borrowed a book on bookkeeping, and read it overnight. The next day, she went in to Besley Wells, applied for the job, and got it. After several years, Besley Wells was bought by Allied Signal, but Addie was able to keep her position in the Loop office. Eventually, however, she was transferred to the office in Beloit, Wisconsin, where she was taught to use a computer. She stayed there for a year before moving back to Chicago.

In all, Addie worked as a bookkeeper for thirteen years before eventually retiring. Arthur died during a surgery the year before she retired. She was sad, of course, she says, but if she were to be honest, it was a relief to not have to care for him anymore.

Despite having to basically raise Hattie herself, work, and take care of an invalid husband, Addie says she was always up for anything. She needed to be busy all the time and always had “a spark” in her eye. Nothing, she says, was too hard for her if she put her mind to it. She had many, many interests and hobbies: ceramics, crocheting, horses, drawing, decorating, home repair, reading, hunting, and fishing, to name a few. She also routinely went to the Art Institute, the Field Museum and the Lincoln Park Zoo and Gardens. If a new interest caught her attention, she would go to the library, find a book on the subject, and learn all about it or teach herself to do whatever it was.

Hattie eventually married and moved to the suburbs, and in the latter years, Addie moved in with her sister, Marie. The two sisters apparently got along very well until Addie had to have bypass surgery in 1990. From there things went downhill, and Addie was eventually diagnosed with COPD and chronic heart failure. The discharge staff advised a nursing home for Addie, especially as she has been given a terminal prognosis and has also entered a hospice program.

Addie is aware of her impending death, but says she is determined to enjoy herself until the very end. She is trying to make the most of the activities at the home but mostly enjoys talking and telling her life story. She is extremely lively and interested in all things around her. Her daughter, Hattie, visits regularly, as does her sister, Marie, both of whom seem to be having a harder time accepting Addie’s situation than she herself is. “What can I say” Hattie asks, “that my mother hasn’t already said? She is an original. A one-of-a-kind, and I’ll miss her so much when she’s gone.”

(Originally written: December 1995)

(Author’s note: Liberty Adelaide Appleby serves as the prototype for the heroine of my Henrietta and Inspector Howard series. Many of the above details of Addie’s story can be found in book one of the series, A Girl Like You.)

The post A Girl Like Addie appeared first on Michelle Cox.

December 20, 2018

“Just One More Chance to Take Care of Her”

Moira Hardy was born on December 16, 1907 in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia to Kenneth Stewart and Effie MacCain, both of Scottish descent. Kenneth was a foreman in a steel mill there, and Effie cared for their eight children: Alan, David, Sonia, Edna, Angus, Beatrice, Moria, and Ewan. Kenneth passed away of a heart condition at age 78, and Effie died at age 92 of “old age.”

Moira Hardy was born on December 16, 1907 in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia to Kenneth Stewart and Effie MacCain, both of Scottish descent. Kenneth was a foreman in a steel mill there, and Effie cared for their eight children: Alan, David, Sonia, Edna, Angus, Beatrice, Moria, and Ewan. Kenneth passed away of a heart condition at age 78, and Effie died at age 92 of “old age.”

Most of Moria’s siblings quit school early and got married, but being one of the younger ones, Moria was encouraged to finish high school. She did graduate in 1925 and then went on to nursing school at St. Vincent’s in New York. She earned her RN, of which she and her entire family were extremely proud. She got a job working for the American Red Cross and traveled all over the United States, which she very much enjoyed.

While still in her twenties, she happened to work with a young doctor by the name of Joseph Hardy at Benedictine Hospital in Kingston, NY. The two fell in love and married in 1935. They bought a home and settled down in Kingston and had two children: Margaret and Edmund. According to Edmund, his parents always seemed relatively happy, but in 1951 they announced that they were getting a divorce. Edmund says that he was never told any of the specifics beyond that they had simply “grown apart.” Edmund suspects that his father may have had an affair, but that it was certainly never talked about. After the divorce, Joseph decided to travel around the United States and died suddenly of a heart attack in 1963.

Meanwhile, Moria found she had to return to work, having given up nursing to stay at home with Margaret and Edmund, who were in their teens at the time of the divorce. She moved to the Bronx with them and was able to find a job at Charles A. Pfizer, which was a pharmaceutical company in New York. She worked there until she retired at age 62, and then took a job at Baptist Nursing Home in the Bronx until 1973, when she quit at age sixty-six.

Fully retired at that point, Moria split her time between gardening, card clubs, and traveling, often going to Vermont to see her daughter, Margaret, or back to Nova Scotia to see her siblings, or coming to Chicago to visit her son, Edmund, and his family. As the years went on, however, all of Moria’s siblings passed away, as did her close friends in New York. She became very lonely and withdrawn, and Edmund eventually convinced her in 1992 to move in with him and his wife, Shirley, in Park Ridge.

Things were going well, apparently, until about six months ago when Shirley noticed that Moria had a bad sore on her leg, which she seemed to be trying to hide behind bandages. Edmund wanted to take her to the doctor, but Moria insisted that as a former nurse, she knew how to take care of a sore and was very offended by what she called his “meddling.”

Eventually, however, Moria did go to see a doctor, who diagnosed it as gangrene. It did not respond to treatment, unfortunately, and Moria had to have her leg amputated. She remained in the hospital for six weeks, during which time a feeding tube also had to be inserted because she had stopped eating. When it came time for Moria to be discharged, the hospital staff strongly urged Edmund and Shirley to put her in a home where she would have full-time care. Edmund was, and still is, racked with guilt about his mother’s amputation and frequently says that if only he had insisted she see a doctor earlier, her leg may have been saved. He was therefore very reluctant to place his mother in a home, telling the hospital staff that he wants “one more chance to take care of her.” Eventually, however, the social worker convinced him that a nursing home would be much better for Moira.

Moira is adjusting relatively well to her new home, but she is very disoriented. She rarely speaks and when she does, she simply asks to go home. She smiles often, however, and seems to like having a roommate. Edmund, on the other hand, is having a very difficult time and needs constant reassurance from the staff that he has made the right decision. He is perhaps unrealistic in his hope that she might recover enough to come back and live with him and is already asking if she might be able to come home for a short break for Christmas.

(Originally written: November 1993)

The post “Just One More Chance to Take Care of Her” appeared first on Michelle Cox.