Michelle Cox's Blog, page 4

November 23, 2023

“It’s Not Over Yet”

Britta Driessen was born on September 10, 1909 in Chicago. Her parents were Valdis Ozolinsh, an immigrant from Latvia, and Ebba Ahlstrom, an immigrant from Sweden. Valdis made his way to America alone, and Ebba also came alone across the ocean to live with her sister, who had found work in Chicago. It is not certain how Valdis and Ebba met, but is thought to have been at a dance. They began courting and eventually married. Valdis worked making wooden boxes, and in the early days of their marriage, Ebba cleaned the offices of the gas company in the evenings. After she gave birth to their only child, Britta, however, she stayed home to care for her.

Britta Driessen was born on September 10, 1909 in Chicago. Her parents were Valdis Ozolinsh, an immigrant from Latvia, and Ebba Ahlstrom, an immigrant from Sweden. Valdis made his way to America alone, and Ebba also came alone across the ocean to live with her sister, who had found work in Chicago. It is not certain how Valdis and Ebba met, but is thought to have been at a dance. They began courting and eventually married. Valdis worked making wooden boxes, and in the early days of their marriage, Ebba cleaned the offices of the gas company in the evenings. After she gave birth to their only child, Britta, however, she stayed home to care for her.

The little family lived on the south side, near 5400 S. Kedzie, and Britta was allowed to go to high school at Harrison High. She then went on to attend Morton Jr. College for two years, as well. While she was taking classes there, she worked in the evenings as a telephone operator for the phone company. Valdis and Ebba were extremely proud of their daughter when she finally graduated and began working as a secretary at Western Electric.

Britta very much enjoyed her job as a secretary and made many friends. One evening, the company held a dance for the employees, and Britta of course attended. She was surprised when one of the supervisors, Arthur Driessen, asked if he could walk her home. She said yes, and she even remembers what they talked about that night. He told her many amusing stories of growing up in Chicago with five siblings and how his grandparents had emigrated from Holland. When they reached her front door, he asked if she would like to have dinner with him some evening. Britta accepted, and the two began dating. They eventually married in 1938.

Britta continued working after their marriage. Not long after, however, there was a reorganization at Western Electric, and Britta was somehow transferred into Arthur’s division. Since there was a company rule which prevented family members working for other family members, Britta saw no choice but to resign. She stayed home and became a housewife, which Arthur seemed to prefer anyway. They lived in the upstairs apartment above Valdis and Ebba, but when her parents decided to sell the building, she and Arthur decided to buy their own place in Park Ridge.

When the war broke out, Britta took over her cousin’s job at the Café Bohemia. It was supposed to be a temporary job in the office, but it stretched on for many years. She and Arthur never had any children, so it seemed to make sense at the time, especially as Britta enjoyed working. She also loved crocheting, making hook rugs, reading, and music. At one point, she tried taking piano lessons, but she found she didn’t have enough time to practice, so she quit. She also loved bowling, and she and Arthur joined many leagues over the years. She was very active in the ladies auxiliary of the Elks, and served on the board of various charitable organizations.

When Arthur finally retired from Western Electric, he had to persuade Britta to quit work as well so that they could travel. She gave it up, reluctantly at first, but then threw herself into traveling. Together they went all over Europe and the United States, including Hawaii and Alaska, and even took a cruise.

Arthur and Britta had many happy years together until he died in the late 1980’s. Britta decided to sell the house and move into a retirement community, where she was able to live independently for about eight years. One day, however, she woke up to find she couldn’t move her legs and subsequently called an ambulance. She was hospitalized for several weeks and then discharged to a nursing home for physical therapy. It is thought that she might yet return to her home. Britta is a very patient, sweet woman who appears eager to please, but she has not completely acclimated to her new surroundings. She fully believes she is going to return home and concentrates on her physical therapy, often practicing walking with a walker up and down the hallways. “I’ve had a good life so far,” she says, “but it’s not over yet!”

(Originally written: August 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “It’s Not Over Yet” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

November 16, 2023

A Wonderful Father and an All-Round Outdoors Man

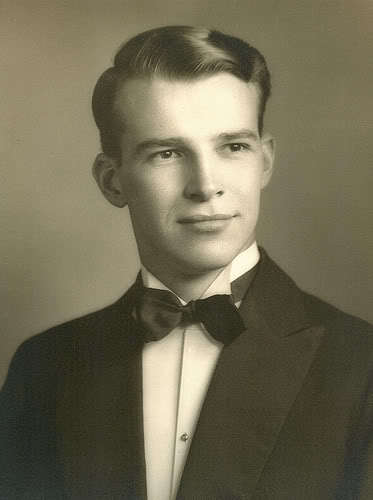

Samuel Werner was born on April 25, 1920 in St. Louis, Missouri to Arne Werner and Kathleen Murphy. Kathleen was born in Ireland and was just a baby when her family immigrated to Texas. When she was only three, the family moved again to St. Louis. Similarly, Arne had been born in Germany, and when he was a small child, his family immigrated to St. Louis as well. Arne and his brothers grew up in St. Louis and ironically ended up fighting in WWI on the American side. Together, Kathleen and Arne had ten children. Only one, James, died in childhood at eight months.

Samuel Werner was born on April 25, 1920 in St. Louis, Missouri to Arne Werner and Kathleen Murphy. Kathleen was born in Ireland and was just a baby when her family immigrated to Texas. When she was only three, the family moved again to St. Louis. Similarly, Arne had been born in Germany, and when he was a small child, his family immigrated to St. Louis as well. Arne and his brothers grew up in St. Louis and ironically ended up fighting in WWI on the American side. Together, Kathleen and Arne had ten children. Only one, James, died in childhood at eight months.

When Samuel was just two years old, the family moved to Chicago where Arne was able to find work as a sheet metal worker. Sam attended grade school and went to high school for a little while before he quit to attend a technical school to learn to be a sheet metal worker like his father. He was soon apprenticed, and when he completed his apprenticeship, he and Arne went into business together, owning their own shop for 34 years.

Sam’s mother, Kathleen, was never in great health and continued to have miscarriages. She was over 300 pounds and had what was called “dropsy.” She died when she was just forty-seven. It was Sam that discovered her. He had just come home from buying his sisters their Easter dresses and found his mother dead in her bed. Arne also died young, at age fifty-eight, of a ruptured spleen.

After his father died, Sam took over the sheet metal shop and eventually married one of his sister’s friends, a girl by the name of Minnie Kunkle. He and Minnie had six children: Peggy, Janet, Doris, Gary, Roger and Arnold. Sam was a very outgoing man who loved music and singing and could play the harmonica, the piano and the organ, all of which he taught himself. His favorite forms of music were Irish ballads and country music because, he once said, the lyrics of both are so sad. For a time he even sang in the choir at his church, St. Timothy’s Lutheran, which was very near their house on Armitage. He was a very outdoorsy sort of man, as well, and also enjoyed hunting, fishing, camping, horseshoes, Ping-Pong, blackjack and sports of any kind. He had “a real zest for life” and was interested in many different things.

For some unstated reason, his marriage to Minnie did not work out, and they divorced in 1971. That same year, Sam decided to remodel a building he owned on Belden and hired a woman by the name of Maria Pasternak to come in and varnish the stairwell. Sam had not met her before, as she had been recommended by someone at work. He was waiting in the foyer of the building to let her in to start the work, and when he saw her, “something just clicked” between the two of them, Maria says. She was a divorced woman, twenty years his junior, with three kids. “It was not an ideal situation by any stretch,” says Maria, but they began dating anyway and married the following year.

Sam helped raise Maria’s three kids: Earl, Patsy and Roy, and became fiercely attached to them, almost more so than to his first six children with Minnie, who had all gone to live with her. He and Maria had a very close relationship and appear to love each other very much, even now. “He was a wonderful father,” Maria says. “He never, ever lost his temper” and seemed to have infinite patience.

Sam continued working at his sheet metal shop until the IRS caught up with him in 1985, and he lost it due to back taxes. It was sold to a new owner, who kept Sam on as an employee. Sam continued working in the shop for four more years until he quit because his arthritis was getting so bad. Then, in early 1995, he also lost his building on Belden due to back taxes and consequently slipped into a deep depression.

Maria believes the stress of these events caused Sam to have a heart attack, from which he spent many weeks in the hospital recovering. When he was finally on the brink of being discharged, his doctor ordered one last test. Maria believes that the staff somehow botched the test because during it, Sam turned gray and stopped breathing. The staff immediately tried to counteract whatever they had done, says Maria, and whisked him off and put him on life support.

Sam spent five weeks in a coma, during which time Maria rarely left his side—talking and singing to him and remembering aloud all of the good times they’d had together. Indeed, Maria partially credits herself for Sam coming out of his coma and was overjoyed when he “came back” to her. He was eventually released to a nursing home to fully recover, but Maria was not happy with the care and has since switched him several times to other facilities. Twice more he was put on life support, and after the third time, Sam supposedly told Maria, “don’t help me anymore,” which meant, Maria says, that he did not want to “go through all of that again.” Somewhat reluctantly, then, Maria agreed to put him in a hospice program at his doctor’s suggestion.

Maria seems satisfied with his current nursing care, but she is very sad and depressed, especially as her son, Roy, is also dying of cancer. She says that she is “utterly heartbroken” and doesn’t know if she has the “strength to go on.” Sam, meanwhile, does not appear agitated or distressed. His cognitive level appears to be very poor, but Maria claims he is still quite alert and responds intelligently to her, though the staff has not specifically witnessed this. Currently, he remains mostly in bed or in one of the day rooms. He does not interact with the other residents, as Maria rarely leaves his side and tends to speak for him.

(Originally written: November 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post A Wonderful Father and an All-Round Outdoors Man appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

November 9, 2023

“Everyone Died But Me”

Eliza Radic was born on May 3, 1906 in Chicago to Bert Halonen and Miriam Jokela. Both Bert and Miriam were born in Chicago as well, though their parents had emigrated from Finland. Bert worked as a “refinisher” of sorts and did silver plating. Miriam was a housewife and took in sewing while she cared for their three girls: Ruby, Eliza, and Catherine.

Eliza Radic was born on May 3, 1906 in Chicago to Bert Halonen and Miriam Jokela. Both Bert and Miriam were born in Chicago as well, though their parents had emigrated from Finland. Bert worked as a “refinisher” of sorts and did silver plating. Miriam was a housewife and took in sewing while she cared for their three girls: Ruby, Eliza, and Catherine.

The Halonen’s unfortunately suffered many losses. Bert and Miriam’s oldest daughter, Ruby, was diagnosed as a child with epilepsy and died as a teenager, though of what exactly it is unclear. Whatever it was, Miriam blamed herself, as the doctors recommended that Ruby be sent away to an institution when it was first discovered that she was an epileptic. Miriam, however, couldn’t bear to send her child away and vowed to care for her at home. So when Ruby died, possibly somehow in conjunction with an epileptic episode, Miriam could never forgive herself and succumbed and died soon after of tuberculosis.

After Miriam died, Bert met and married a woman by the name of Norma Fielding, whom he had met at a party. Eliza says that she didn’t mind her stepmother and that Norma was kind to her and her remaining sister, Catherine.

Eliza graduated from 8th grade and got a job working for Sears, Roebuck and Co. She worked there until she married Walter Radic, who worked in a paint factory. She met him at a carnival put on by her church, Our Lady of the Mount, and the two of them began dating. After a year, they married and moved into the bottom flat of the building her father owned in Cicero. Thus Eliza went from living in the upstairs apartment with her father and Norma to the downstairs apartment with Walter.

When WWII broke out, Walter enlisted in the army and was stationed in France. He was injured after only a few months of being there, however, and was shipped back home to recover. He was able to get his job back at the paint factory, but “he was never the same,” Eliza says. Just as she was adjusting to having her husband back, however, Eliza’s stepmother, Norma, died of a brain hemorrhage, throwing them all into another episode of grief.

Eliza and Walter very much wanted children, but “none came.” At first Eliza was very saddened by their childlessness and, combined with the loss of her stepmother, went into a brief depression. Eventually, however, she put it behind her and tried to concentrate instead on her job and her sister, Catherine, who still lived at home with Bert.

Catherine was always considered to be “a little slow,” and seemed destined to be a spinster. She surprised everyone, however, when she one day announced that she was getting married to a man who drove a bread delivery truck. They had met at the movies, she told everyone, though no one could remember her ever going to a theater. Nevertheless, at age fifty, Catherine got married, which was a nice bit of happy news for the family, despite any misgivings they might have had regarding Catherine’s ability to be a housewife and manage a home. Apparently, she managed just fine, and she and her husband, Jimmy, seemed happy with each other. It was not to last, however, as Catherine died just a year later of cancer.

Eliza was always a little bit shy, and it was Walter who encouraged her over the years to join many ladies groups at church and in the community. Eliza loved crocheting, so she volunteered to crochet a blanket for each new baby baptized at her church, which was still Our Lady of the Mount. She also loved to bake and to read and spent many hours volunteering at the library. She and Walter did a bit of traveling, though never too far from home, as Walter didn’t like to take off too much time from work. Eliza says she loved to travel and wished she could have done more. Their plan was to take a trip to Europe once Walter retired, but, again, tragedy struck, and Walter died suddenly of a heart attack in his fifties.

After Walter passed away, Eliza lived alone in the apartment in Cicero and became increasingly paranoid as time went on, reports her long-time neighbor, Helen Simcek. Helen says that Eliza became convinced that someone was coming into the house and stealing items, which Helen later found hidden around the house. Eliza became increasingly confused, often repeating “everyone died but me,” over and over, among other things, so much so that Helen finally convinced her to let her take her to a doctor, who eventually diagnosed Eliza as having some sort of brain disorder. As Eliza has no family or friends left, Helen volunteered to help her settle into a nursing home and to bring some of her things.

Surprisingly, Eliza is making a smooth adjustment to her new environment. At times she is confused, but overall she is pleasant and sweet. She has started crocheting again and likes to read, out loud, the introductory materials she received from the home upon her admission, such as the Resident Bill of Rights or the form letter from the administrator. She enjoys reading and commenting on this material very much and likes to discuss its finer points. She has yet to make any close friends but enjoys sitting with others.

(Originally written September 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Everyone Died But Me” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

November 2, 2023

Forever His Bride . . .

Esther Andrews was born on February 14, 1910 in Chicago to Lester Simonis and Nellie Baird. It is thought that Lester was an immigrant from Latvia and that Nellie had been born in Scotland. According to family legend, shortly after Nellie arrived in America as just a baby, both of her parents died, and she was placed in an orphanage in Chicago. At fifteen, she began working as a maid, where she met Lester Simonis, who delivered the daily milk to the house she was employed at. Lester eventually proposed to Nellie, who accepted him, and they were married soon after. Nellie quit her job to care for their eventual four children: Verla, Clifford, Stella and Esther, while Lester continued working as a milkman. When Esther was just a baby, however, Lester died, though no one in the family seems to remember of what. Nellie took in washing for a while to make ends meet, and eventually ended up marrying Daniel Juric, a kind man, who worked in various factories around the city.

Esther Andrews was born on February 14, 1910 in Chicago to Lester Simonis and Nellie Baird. It is thought that Lester was an immigrant from Latvia and that Nellie had been born in Scotland. According to family legend, shortly after Nellie arrived in America as just a baby, both of her parents died, and she was placed in an orphanage in Chicago. At fifteen, she began working as a maid, where she met Lester Simonis, who delivered the daily milk to the house she was employed at. Lester eventually proposed to Nellie, who accepted him, and they were married soon after. Nellie quit her job to care for their eventual four children: Verla, Clifford, Stella and Esther, while Lester continued working as a milkman. When Esther was just a baby, however, Lester died, though no one in the family seems to remember of what. Nellie took in washing for a while to make ends meet, and eventually ended up marrying Daniel Juric, a kind man, who worked in various factories around the city.

Esther received a somewhat sketchy education, only attending school through the fourth or fifth grade. She quit school and got various odd jobs until she found a permanent place at the Excelsior Seal Furnace Company on Goose Island at age thirteen. Her job was to pack the parts in boxes to be shipped out.

When she was nineteen, however, her mother, Nellie, died unexpectedly of the flu. Esther was the only one still left at home, so for a while she and her grieving stepfather, Daniel, tried to make the best of it. Daniel, however, went into a deep depression, and Esther found it hard to cope with him just on her own. She appealed to her older sister, Verla, who agreed to take in both Esther and Daniel, provided that Esther “do her part” around the house. Esther, eager to be relieved of the sole responsibility of caring for their stepfather, agreed to her sister’s conditions, but soon lived to regret it. Verla gave Esther long lists of chores that she was expected to complete each day, including gardening, in addition to her working at Excelsior Seal.

This routine continued for nine long years until Daniel met another woman, Mary Budny, at a dance. The two married six months later, and Daniel finally moved out of Verla’s home, leaving Esther behind, who, at age 28, was beginning to think life had passed her by. She hated living with Verla and her husband, Bob, and resented being “their slave,” but she couldn’t see any other option.

Esther had nearly resigned herself to being a spinster until one day, September 14, 1938, to be exact, a young man by the name of Glenn Andrews walked into Excelsior Seal Furnace Company looking for a job. Glenn was hired on the spot, and it was Esther’s job to show him around. The two took a liking to each other, and before the day was out, Glenn asked her out on a date. Esther excitedly said yes, and Glenn took her to the Aragon ballroom.

Esther and Glenn dated for four years before they were married on January 22, 1944. Four days later, Glen left for the war. He served for 27 months in Japan and the Philippines and says that it was the many, many care packages of cookies and candy and letters from Esther that got him through. When he came back, miraculously “safe and sound,” he and Esther had to “relearn each other” all over again. Esther had spent the war still living with Verla and Bob, who had not altered their treatment of her despite the fact that she was now a married woman.

When he returned, Glenn got his job back at Excelsior, and he and Esther rented a little apartment on Sedgewick. Their neighbors were Ada and Dieter Kahler, a German couple with three kids, whom they got to know very well. Eventually the four of them went in together and bought a two-flat. Both families lived there for the next 27 years and became best friends. Glenn and Esther never had any children, so they enjoyed helping with and watching Ada and Dieter’s children, whom they became very close to over the years.

Glenn and Esther were very active in the United Steel Workers Union and served on many, many committees. They enjoyed visiting with friends and playing poker and loved going to see movies. Their biggest passion, however, was traveling. They spent every vacation traveling, and in 1979, when Esther finally retired from Excelsior, after working there for 54 years, they decided to travel full-time. They spent the next 14 years traveling to such places as New York, Wisconsin, Mexico, Lake Louise, Niagara Falls, New Orleans, Florida, Mt. Rushmore, California, Hot Springs, the Grand Canyon, and many, many more. They traveled by car, train, and even bus on some occasions.

After so many years of enjoyment with each other, “Esther began to change,” says Glenn, in the early 1990’s. She became increasingly confused and was often found wandering the neighborhood. Also, says Glenn, she put on “layers of layers of clothes” and even once chased him through the house with a knife. Unable to understand her diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, Glenn tried to care for Esther himself for about eleven months before he finally gave in to the doctor’s suggestion that he admit her to a nursing home, heartbreaking though it was for him to be separated from her.

Technically, Glenn still lives in the two-flat that he and Esther purchased with the Kahlers, though only he and Ada are left, as Dieter died years ago and their children have since moved away. Nonetheless, Glenn prefers to spend his days and evenings at the nursing home. Here he sits with his beloved Esther, 365 days a year, wheeling her about the home, taking her outside to sit in the gardens, or bringing her to various activities. Esther does not really participate in any of the home’s events, however, and just sits quietly with her eyes closed. If asked a question, she usually gives a garbled, nonsensical answer.

Glenn does the talking for her as he holds her hand. He knows every single resident and staff member. He loves to talk to whomever will stop long enough and especially enjoys telling stories of he and Esther’s traveling days. When the staff ask him why he doesn’t just make it official and move here, too, Glenn says that he couldn’t do that to poor Ada. But he remains devoted to Esther, coming every day and always lovingly calling her “my bride,” though he often sadly states that she is just a shell of the lovely, sweet woman she once was.

(Originally written May 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post Forever His Bride . . . appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

October 26, 2023

“Everyone Says I’m Crazy”

Cleo Newman was born on February 10, 1911 in Kewanee, Illinois to Peter Wyrick and Lorene Crawford. It is believed that Peter was a Polish immigrant and that Lorene was of English descent. Peter had apparently been a farmer in Poland and found work on various farms throughout the Midwest after he immigrated here. Eventually he married Lorene Crawford and was able to buy his own small farm in Kewanee. While he worked the farm, Lorene cared for their eleven children, only eight of whom lived to adulthood.

Cleo Newman was born on February 10, 1911 in Kewanee, Illinois to Peter Wyrick and Lorene Crawford. It is believed that Peter was a Polish immigrant and that Lorene was of English descent. Peter had apparently been a farmer in Poland and found work on various farms throughout the Midwest after he immigrated here. Eventually he married Lorene Crawford and was able to buy his own small farm in Kewanee. While he worked the farm, Lorene cared for their eleven children, only eight of whom lived to adulthood.

The Wyricks were extremely poor, and Cleo only went to school through the eighth grade before quitting to find a job. When she was 18, she decided to move to Chicago to look for work and stayed with an older sister. She worked in various factories and restaurants and eventually met a man by the name of Nelson Newman while she was waitressing.

Nelson was older than Cleo and had been married before, but the two of them began dating and were married soon after. Cleo was surprised to find that Nelson expected her to continue working as a waitress to support them while he went back to school to become a history teacher. After three years of this, Cleo became pregnant, which infuriated Nelson, as it interfered with his plans of finishing his degree. When the baby, Marcella, was born, Nelson was forced to stop school and find a job, which he very much resented. Cleo and Nelson fought constantly, and eventually, when Marcella was just three years old, they divorced. Nelson went on to finish his degree, become a history teacher, and marry two more times. He died on Memorial Day in 1984, and Cleo has never ceased to hate him.

In fact, Nelson became Cleo’s focal point for any bad thing that ever happened to her for many, many years. After the divorce, Cleo moved from Downers Grove back into the city with Marcella where she found work again, but she became increasingly angry and bitter as the years went on. Marcella says that it was after the divorce that her mother really “went off the wall,” though she was always “a bit off.” Frequently, Cleo would complain that “everyone says I’m crazy.” Cleo resented having to care for Marcella, saying that “no one’s going to want me with a kid.” Marcella always felt “in the way,” and was taught to hate her father, Nelson. Cleo often told Marcella outrageous stories about Nelson, which Marcella was sure were lies about him, such as the fact that he supposedly held Cleo by the ankles and bounced her on the floor while she was pregnant, hoping she would miscarry. Marcella, though she was allowed little contact with her father, refused to believe this of him.

As Marcella grew older, Cleo’s relationship with her daughter grew more and more troubled. Cleo became very suspicious and jealous of Marcella and would accuse her of many, many untruths. For one thing, Cleo accused Marcella of being jealous of her beauty, though it was Marcella that was growing into an increasingly beautiful girl. In reality, it was the opposite, Marcella says. It was her mother who was becoming increasingly jealous of her. “You could never talk to her,” Marcella adds. “You could never reason with her.”

When Marcella was in sixth grade, Cleo married a man named Nick Moretti, but by the time Marcella was in high school, the two had already divorced. Marcella thinks it odd that even though Nick was also “no great catch,” Cleo’s anger and bitterness remained directed at Nelson. For example, Nick could be cruel in his own way, but Cleo hardly ever mentioned him in her rants, only Nelson, who had become a sort of obsession. Her mother had other obsessions, too, Marcella reports, one of them being health and fitness. She became a vegetarian, stopped going to doctors, and did calisthenics, including push-ups, into her 80’s. She abhorred doctors and claims to have cured herself of various illnesses and injuries, including cancer and a broken arm. Again, says Marcella, “no amount of reasoning ever worked with her.”

Cleo also became obsessed with Marcella’s social life, limited as it was. Cleo would constantly chastise Marcella for “sleeping around” and frequently called her a “pregnant slut,” even though Marcella had yet to ever even kiss anyone! After Marcella finished high school, she got two jobs to try to help support herself and her mother, as Cleo only worked sporadically during those years. When Marcella would come home late from her night job, Cleo was always waiting there to accuse her of “running around,” refusing to believe that Marcella was actually out working, not out “sleeping with a guy.” Finally, Cleo became so incensed at Marcella’s imagined behavior that she kicked her out of the house.

Marcella was then forced to find her own apartment and tried to make a life for herself separate from Cleo. Eventually, she met a nice man by the name of Joseph Mueller, and they married. Marcella says that they had to practically beg Cleo to attend the wedding, and when Marcella quickly became pregnant, Cleo’s response was “now she’ll find out what it’s all about to raise a kid.” As the years went on, Cleo showed little interest in Marcella or her grandchildren, as they came along, and the mother and daughter drifted even farther apart.

With Marcella out of her life, Cleo apparently became even more distrustful and suspicious of everyone around her. She spent her days riding downtown on the bus, going from lawyer to lawyer, attempting to sue people for stealing her money. The main recipient of her wrath and blame now became her accountant, one Mr. Shum, whom she decided had stolen all of her money. She also accused Marcella of somehow conspiring with Mr. Shum to steal her money. Marcella later laughed at this accusation when she heard it, saying she had never even met a Mr. Shum. Cleo persisted in her delusion, often saying that “Shum wants to ‘do’ me, though I know he’s already ‘doing’ Marcella.”

When not going from lawyer to lawyer, Cleo also spent time going from bank to bank, opening and closing her accounts, saying that someone had stolen her bank books. Years later, Marcella found boxes and boxes of old bank books tucked away around the house where Cleo had apparently hidden and then forgotten about them.

Likewise, Cleo began calling the police on a somewhat regular basis, claiming that she had been the victim of a robbery. Each time the police would come and point out that no locks were broken and no windows smashed. Still, however, Cleo would insist that something had been stolen, even a small thing like a box of tweezers. Or she would point to empty hangars in her closet as if to say, “See? There’s nothing on them, so the clothes must have been stolen!”

The only person in Cleo’s life at this time was her brother, Bill, who had been injured in a motorcycle accident at age twenty-one and in his old age went to live with Cleo. “Uncle Bill,” says Marcella, was also “a little on the crazy side.” Bill lived with Cleo, absorbing her strange stories and theories until he died in the early 1990’s. After that, Cleo latched onto his daughter, Mary, who, Marcella says, was “easily manipulated.”

After Bill died, Mary indeed became Cleo’s companion and would drive Cleo around to various law offices and banks, still accusing people of stealing from her. After a couple of years of this, however, even the sweet, gentle, accommodating Mary began to crack under the strain. Cleo sometimes called her five times in a half hour, wanting something or asking the same question over and over. Mary also began getting calls in the middle of the night from the police, saying that they had picked up Cleo, wandering, lost, around the neighborhood. Finally, in desperation, Mary called her cousin, Marcella, to appeal for help. Marcella, who had been out of her mother’s life for over thirty years, had no idea that Cleo had “gotten so bad.” She apologized to Mary for Cleo’s behavior and came back into the picture to help. When the police then began calling her in the middle of the night, she decided that it was time to put Cleo in a nursing home.

Needless perhaps to say, Cleo is very resentful of her placement in a nursing home and remains angry, disoriented and depressed. She repeatedly accuses Marcella of dumping her here and complains that “I’m not sick. I don’t belong here.” Marcella is concerned for her mother’s safety and security, but is neither emotional nor affectionate with Cleo. She says that she feels sorry for her, as she has obviously been mentally ill all these years, but she has no emotion left for her mother and does not feel guilty about placing her here. Cleo refuses to acclimate or meet other residents and switches quickly between extreme anger and tears, often saying “I want to get out of here!”

(Originally written: July 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Everyone Says I’m Crazy” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

October 19, 2023

A Neighborhood Gem!

Herbert Jones was born on May 14, 1899 on a farm in Bolton, Mississippi. His parents, Jesse and Hattie Jones, owned the small farm they worked, which they were very proud of, as Jesse’s father had been a slave. There were thirteen children in the Jones’ family, and Herbert was the youngest boy. He went to school until the seventh grade and mostly helped his father and brothers around the farm.

Herbert Jones was born on May 14, 1899 on a farm in Bolton, Mississippi. His parents, Jesse and Hattie Jones, owned the small farm they worked, which they were very proud of, as Jesse’s father had been a slave. There were thirteen children in the Jones’ family, and Herbert was the youngest boy. He went to school until the seventh grade and mostly helped his father and brothers around the farm.

In his early twenties, Herbert decided to go to Chicago to look for work. World War I had just ended, and he hoped to find something more than what the farm in Mississippi could offer him. He found a job at International Harvester and worked his way up over the years, eventually becoming a molder.

Herbert kept mostly to himself. He made a few friends and enjoyed working with electronics and carving wood. He joined a church, Apostolic Church of God, which was a Baptist church, and he lived in the South Shore neighborhood on the far south side. When he was in his forties, he happened to meet a young woman by the name of Pauline Everts at a prayer group at church. Pauline was only in her twenties, but Herbert quickly fell in love with her. He was very patient, and courted her very slowly, becoming her friend first and then tentatively asking her out on a date to an ice cream parlor. To his great surprise and excitement, she said yes. Pauline says she had no idea when they started dating that he was twenty years older than her or she would have said no! Herbert was one of those people, she says, who had a young face. By the time he told her he was in his forties, it was too late, however; she was in love with him. They dated for just six months and then got married. Some of his siblings from Mississippi came up for the wedding, but his parents had already passed away at this point. Together, Herbert and Pauline had five children: Herbert, Jr.; Mae; Clifford; Lena; and Lucille.

Pauline says that Herbert was a wonderful father, that he was a very patient, understanding man. He had a great sense of humor, but there was also a “no-nonsense” side to him, too. He was a great role model, she says, not just for their children, but for many of the neighborhood kids. He knew all of them, and they all felt they could talk to him. Pauline says that when he spoke, he meant it, and all the children knew that, too. If he said something, they obeyed it. Pauline says that whenever Herbert was upset or troubled by something, he would sit quietly somewhere for a long time, thinking, until he came up with a solution.

Herbert had such a positive influence on his neighborhood that in 1992, Ebony magazine did a feature on him for a special father’s day edition, alongside Winston Marsalis. The article illustrated how many lives Herbert had touched beyond his own five children and how his “patient, honest, no-nonsense style” had contributed so directly to the success of so many kids in the neighborhood. Herbert was extremely proud of the accolades from Ebony Magazine, but he remained a very humble man, often saying throughout his life that he was really “just a farm boy at heart.”

Herbert and Pauline were still living in their apartment on South Shore Dr. until July of 1995 when Herbert came down with pneumonia at age 96. At the hospital, it was discovered that his kidneys were also not in the best shape, either. In November of that same year, he was diagnosed with CHF and anemia and was given a blood transfusion. His kidneys, the doctors also observed had also worsened, but because of his CHF, they felt that dialysis might be too hard on his heart. He was discharged home, but was readmitted within several months for being listless, tired and weak. This time, the doctors felt they had no choice by to attempt dialysis, which his heart thankfully managed to handle. He was discharged, however, to a nursing home, where he remains unresponsive most of the time.

Pauline and various members of the family visit daily, though Herbert does not interact with them. Pauline is upset by Herbert’s placement and does not seem to accept that it is permanent. She is still hopeful that he will return home. She loves to talk about her life with him and the wonderful man he was. It is very difficult for her to see him this way, and she cries often. Her children and grandchildren have been very supportive, however, and visit frequently.

(Originally written February 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post A Neighborhood Gem! appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

October 12, 2023

“I’ve Had a Lovely Life.”

Sadie Davis was born on December 2, 1920 to Ervin Olmskirk and Caroline Fredericks in Clarkson, Nebraska. Ervin worked in a bank, and Caroline cared for their ten children: Sadie, Irving, Louis, George, Thelma, Rose, Francis, Fred, Ruby, and Gladys.

Sadie Davis was born on December 2, 1920 to Ervin Olmskirk and Caroline Fredericks in Clarkson, Nebraska. Ervin worked in a bank, and Caroline cared for their ten children: Sadie, Irving, Louis, George, Thelma, Rose, Francis, Fred, Ruby, and Gladys.

Sadie was a bright child and after finishing high school, won a two-year scholarship to Wayne State College in Wayne, Nebraska. This was following the Great Depression, however, so when the two years were up, Sadie could not afford to stay longer, though she dearly loved her college experience and dreamed of becoming a teacher. She contemplated ways that she could earn the money herself, but before she could come up with any answers, she received word that her father had been killed in a freak accident, which caused her to have to hurry home. Ervin had apparently been out trimming trees when a large branch fell on him, crushing his skull and killing him instantly. He was only forty-six years old. At the time of her father’s death, Sadie was nineteen and her youngest sibling had just turned one. Sadie then naturally gave up all hopes of furthering her education and began looking for a job to help support her mother.

The family had barely time to recover from Ervin’s death when they received word that Ervin’s brother, Anthony, who was living in Chicago, had also died. With her husband recently deceased, ten children to take care of and little money, there was no way that Caroline could make the journey to Chicago for her brother-in-law’s funeral, though she fretted endlessly about who would represent the family. Finally, she decided that she would send Sadie with an aunt and uncle who lived in nearby Omaha and who were planning on travelling up to the funeral on the train. Sadie was chosen because she hadn’t yet found a job and because she was the same age as Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom’s only child, Imogene, who was also making the journey. That way, Aunt Betty said, Imogene would have someone to talk to.

On the long train ride to Chicago, Sadie and Imogene enjoyed getting to know each other again, having not seen each other for several years. Sadie told Imogene all about her college days at Wayne State, and Imogene told her all about living in the big city of Omaha. Together the girls schemed that if they could somehow find jobs in Chicago while they were there for the funeral, they might be allowed to stay.

The funeral, it turned out, was all the way north of the city in a small vacation village called Fox Lake. Many relatives showed up from out of town and rented small cottages rather than staying in hotels. Sadie and Imogene began to look for work right away, though not much could be found in Fox Lake. As it turns out, Imogene went to the beach one day without Sadie, who stayed behind in the cottage because she was feeling ill. Later in the day, feeling a little better, Sadie ventured out doors on her own and was intrigued by a young man working on a sail boat in the yard next door. The two began talking over the fence and fell into an easy conversation. His name was Lowell Davis.

Eventually, after many days of talking over the fence, Lowell asked Sadie out on a date, and she accepted. They had a wonderful time together and found it very easy to talk, but their new relationship threatened to be over just as it was beginning, as Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom were planning to return to Nebraska soon. Lowell decided drastic measures were in order, so he sold his boat to buy Sadie an engagement ring and proposed to her.

Sadie said yes and arranged to stay with other relatives in the city until the wedding could be planned. She found a job downtown in a millinery shop, and offered to help Imogene find something, too. Aunt Betty and Uncle Tom refused to hear of any such nonsense, however, and despite Imogene’s pleading, insisted that she return to Omaha with them.

Eventually Sadie and Lowell married and moved to the northwest side of Chicago. When WW II broke out, Lowell dutifully joined the navy. Left alone, Sadie considered moving back to Nebraska to live with her family for the duration of the war. In the end, however, she decided to stay in Chicago and wait for Lowell to come back. When Lowell eventually returned from the war, miraculously unharmed, he got a job as a loan officer at a bank, oddly like her father, Ervin. Sadie continued working in the millinery shop until her first baby was born. In all, Sadie and Lowell had four children, all girls: Shirley, Gloria, Brenda and Virginia. Though she mostly remained a housewife, Sadie sometimes worked as a substitute teacher and also taught CCD classes at her church. She was also very involved in the Girl Scouts and other community organizations. Her hobby was writing the family history going generations back.

Lowell died in 1973, after which Sadie continued living alone, though she was very active. Only recently, when she has been diagnosed with Hodgkin’s, has she begun to need help. She was admitted to the hospital due to complications with her condition and was then discharged to a nursing home. All of her daughters live out of town, except Shirley, who visits regularly and is very concerned for her mom. She puts on a brave face in front of Sadie, but she frequently cries to staff from the guilt of not being able to care for her mom at home.

Sadie, meanwhile, is making an excellent transition, though she is sometimes very weak and tired. She enjoys intellectual conversations or sitting and watching television with other residents. She does not appear distressed or upset, but says that “life is what you make it. I’ve had a lovely life.” Her daughter, Shirley, concurs, relating that her mother has always been a very positive person, no matter what the circumstance.

(Originally written: March 1994)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “I’ve Had a Lovely Life.” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

October 5, 2023

He Asked His Family to Find Him a Bride

Francisco Alvarez was born on September 8, 1913 in Cuba to Felipe Alvarez and Maria Acosta. Felipe worked as a chef in Havana, and Maria cared for their nine children, of whom Francisco was the oldest.

Francisco Alvarez was born on September 8, 1913 in Cuba to Felipe Alvarez and Maria Acosta. Felipe worked as a chef in Havana, and Maria cared for their nine children, of whom Francisco was the oldest.

Francisco was an extremely intelligent child and was able to attend a couple of years of high school before he was forced to quit and help his father in the kitchens of the restaurants where he worked. It wasn’t a job Francisco particularly enjoyed, but he did love good food. As a young man, he also loved playing the saxophone and listening to classical music. “He was very much a loner,” however, reports his sister, Eldora. He was always “hot-tempered,” she says, and “he didn’t have many friends.” He worked a variety of jobs in Cuba, mostly in restaurants, before deciding to try his luck in the United States.

Francisco arrived in Chicago in 1956 and got a job working for Hart, Schaffner and Marx in one of their downtown warehouses. He continued to be a loner, however, and over the years only managed to make two friends with whom he sometimes met up to play dominoes. When he wasn’t working, he took some trips around the United States, and especially liked going to see New York. Eldora says the family was always urging him to settle down and get married, but Francisco always ignored them, saying that there was plenty of time to get “tied down.” They were hopeful, Eldora says, that when he left to come to the United States, he would perhaps find someone there.

After three years in the United States, however, and at age forty-six, he was still single. His family was surprised, then, to get a letter from him one day in which he expressed his desire for them to find him a bride. This of course caused much excitement in the family, as they set about looking for a potential mate for Francisco. Finally, they were able to set him up with Bonita Delgado, who was the daughter of a friend with whom Felipe worked. Francisco returned to Cuba for a visit and to meet his potential wife. He went on several dates with Bonita and, finding her agreeable, promptly proposed to her.

His family was surprised but delighted when she said yes. The two were married quickly in Cuba and then returned to Chicago. Bonita found work in a factory, and Francisco continued at Hart, Schaffner and Marx. It proved not to be a happy marriage, however. Francisco was still hot tempered and was apparently verbally abusive to Bonita, so after only a couple of years, the marriage broke up and Bonita returned to Havana.

Shortly after his divorce, Francisco’s parents, Felipe and Maria, decided to immigrate to the United States and came to Chicago to be near Francisco and two of their daughters, Eldora and Flores, who had also moved to the city. It was Felipe’s plan to get a job in a restaurant, but he died unexpectedly after only being in Chicago for about a month. After Felipe’s death, Maria moved in with Francisco and became completely devoted to him. Endlessly she urged him to find another wife, so he continued to date various women, if only to please her.

According to Eldora, Francisco loved to buy women expensive gifts, but he hated being thanked for them. As soon as a woman gushed her thanks to him for a gift he had bought, he “dropped her immediately,” Eldora says. He would then become acerbic and abusive, and the relationship would end. Meanwhile, his mother continued to pamper him and cooked beautiful, elaborate dinners for him until she died at age 97 in 1989.

Francisco was devastated by his mother’s death and repeatedly expressed his desire to “kill himself,” saying that he wanted “to die.” Eldora and Flores both suspect that he may have actually tried to kill himself at one point but that the attempt wasn’t successful.

To make matters worse, within a couple of years of his mother dying, his only two friends also died. From that point on, Francisco started having health problems and described his legs as suddenly “crippling up.” He began having difficulty walking, so his sisters took him to Miami, “where the climate is better,” and helped him move into a nursing home there. “It was a nice one,” Eldora says, “right on the beach.” Francisco hated the food at that particular facility, however, and soon switched to a different one. Eventually his legs improved, and he returned to Chicago for a visit in 1995 and was able to walk with just the aid of a cane. When he returned to Miami, however, he unfortunately slipped and fell and was then confined to a wheelchair.

After his fall, Eldora and Flores rarely heard from their brother, and they became more and more worried about him. They had been in the habit of talking on the phone with him once a week, but even that eventually ceased. Finally, the two sisters decided to go down and visit him. They were shocked when they discovered he was now “drugged” and on a “locked ward.” They protested to the administration and the nurses, who all said that Francisco was violent, abusive and out-of-control. Both Eldora and Flores, who “don’t believe in doctors” insist that their brother is “not crazy, he just has a bad temper.”

They promptly removed him from the nursing home in Miami and admitted him to a different nursing home on Chicago’s NW side, close to their own families. Francisco is not adjusting well to the new facility, however and continues to be verbally abusive to the staff as well as to other residents. Eldora and Flores come to visit him regularly and do not seem affected by his verbal abuse, which they dish back to him, suggesting that this behavior was “normal” in their family. Eldora provided all of the above information, as Francisco refuses to answer any questions posed to him by the staff. He is able to speak and understand English, but he usually refuses to do so. Eldora reports that he is confused, thinking he is still in Miami and that he has his days and nights mixed up. She and Flores want him to be happy here, but they do not have much hope, as he has always been such a negative person.

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post He Asked His Family to Find Him a Bride appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

September 28, 2023

“Little But Mighty”

Minnie Conrad was born on November 2, 1905 in Florence, South Carolina to Irvin Julian Wentworth Lewis, who was of English descent, and Victoria Edmundson, who was of Swedish descent. Irvin, it seems, was quite the Renaissance man and worked as a musician, a music teacher, a photographer and even a pharmacist at times, making and selling his own ointments. Victoria stayed at home and cared for their ten children: Roger, Elva, Jerome, Perry, Roscoe, Leola, Geraldine, Minnie, Marshall and Clinton. Surprisingly, all ten children lived to adulthood, though Victoria herself died when Minnie was just four years old. Unheard of at the time, Irvin kept and raised all ten of the children on his own. Minnie says that her father had a real zeal for life. He was always energetic, busy, and outgoing and had a “larger-than-life” personality, which, Minnie says, she had the good fortune to inherit.

Minnie Conrad was born on November 2, 1905 in Florence, South Carolina to Irvin Julian Wentworth Lewis, who was of English descent, and Victoria Edmundson, who was of Swedish descent. Irvin, it seems, was quite the Renaissance man and worked as a musician, a music teacher, a photographer and even a pharmacist at times, making and selling his own ointments. Victoria stayed at home and cared for their ten children: Roger, Elva, Jerome, Perry, Roscoe, Leola, Geraldine, Minnie, Marshall and Clinton. Surprisingly, all ten children lived to adulthood, though Victoria herself died when Minnie was just four years old. Unheard of at the time, Irvin kept and raised all ten of the children on his own. Minnie says that her father had a real zeal for life. He was always energetic, busy, and outgoing and had a “larger-than-life” personality, which, Minnie says, she had the good fortune to inherit.

Minnie managed to graduate from high school and then moved to Evansville, Indiana to live with her older sister, Leola. Minnie found a job as a telephone operator and went to beauty school at night. After that, she went to Branwell’s Business School and hoped to open her own beauty shop someday. Along the way, she met Wayne Philip Conrad, who was a journalist with the Evansville Courier. He was much older than Minnie, and Leola advised her to stay away from him, but Minnie was intrigued. Wayne pursued her, often taking her dancing or out with his reporter friends from the Courier, and Minnie soon fell head-over-heels for him.

The two got married, and soon after, Minnie had a baby girl, Elizabeth. When Elizabeth was just 18 months old, however, Minnie discovered that Wayne was having an affair. Wayne insisted that the affair meant nothing, but Minnie wouldn’t listen and insisted they divorce. Neither of them ever married again, however, and they kept in touch for the rest of their lives until Wayne died in 1974.

After the divorce, Minnie pursued her dream and opened her own beauty shop, working long hours to make a living for her and Elizabeth. When she wasn’t working, she loved horseback riding and going to beauty shows and horse races. She also loved to play the piano and sing, and later in life, she decided to learn to swim. Her real passion, though, she says, was dancing, and she still likes to dance even now in her eighties!

Minnie remained in Evansville until the 1960’s when many of her friends began moving away to other locales. Elizabeth had likewise long ago left home, having gotten married and moved to Chicago. Thus, Minnie decided to sell her shop and also move to Chicago to be near Elizabeth and her three children. Once there, she set about applying for an Illinois beauty license. Once she got it, she was hired by Helene Curtis as a hair color representative and was then accordingly sent all over the United States. Minnie adored this job and loved every second of her travels. “They treated me like the Queen of Sheba!” she says proudly.

Minnie is a charming, fascinating lady who loves to talk, especially about her career and her many adventures, both as a rep for Helene Curtis and as a business owner, and will willingly introduce herself to anyone. Elizabeth describes her mother as “a survivor,” saying that raising a child alone in the South in the thirties and forties was “no easy task.” Elizabeth says that her mother had a strict routine and never varied from it and that she had two favorite sayings: “Little But Mighty!” and “Poor But Proud!” Elizabeth says that her mother was a great inspiration to her and to many other women in the South at that time. She also believes that Minnie never stopped loving her estranged husband, Wayne, but that both of them were too proud to ever reconcile. It is a source of her great sadness, Elizabeth says, that she grew up without her father.

Minnie lived a full, active life on her own until just about six years ago when she started to mentally slip a bit. Elizabeth’s son, Adam, went to live with Minnie for a number of years to help her. During this past year, however, Minnie has become more and more confused, including forgetting how to open the front door with her key, leaving the stove on, forgetting to eat, and even forgetting her own face. Adam says that many times his grandmother became hysterical, saying that a stranger was in the apartment when it was merely her own reflection in the mirror. When Adam eventually moved out to pursue a job in another state, Minnie’s paranoia and anxiety increased so much that she had to move in with Elizabeth.

For a while Elizabeth coped by having Minnie go to adult daycare, which helped somewhat, but her mother still needed constant attention in the evenings. Finally, Elizabeth made the decision for her to be admitted to a nursing home and says that she does not feel guilty, as she believes she did everything she could for her mother.

Minnie, for her part, seems to be making a relatively smooth transition. At times she is capable of having an intelligent conversation and loves to join in activities, but at other times, she seems to experience episodes of confusion, particularly regarding Elizabeth. Perhaps because she spent two years in a day facility, she often becomes irritated when Elizabeth does not arrive to pick her up and “take me home.” She needs frequent reminders that this is her permanent home now. Overall, however, she is a sweet, zestful lady and is usually happy and content.

(Originally written: March 1995)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Little But Mighty” appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.

September 21, 2023

“Rats as Big as Cats!” and Other Stories from the Wonderfully Philosophic Oscar S. Cohen

Oscar S. Cohen was born on June 11, 1921 in New York City to David Cohen, an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Gladys Feldt, a native New Yorker. David worked as a shoe salesman, and Gladys cared for their two children: Oscar and Oliver. Oscar describes his parents as extremely intelligent and remembers that his mother spoke beautifully. She could speak to anyone, he recalls, “doctors, lawyers, the woman down the street.” Oscar believes he inherited his parents’ intelligence, but sadly discovered it too late. He feels that he was not given enough guidance or encouragement and didn’t realize his potential until later in life. He learned a lot in grammar school under his strict, old-fashioned Irish teachers, but when he went to high school, “I didn’t learn a damn thing.”

Oscar S. Cohen was born on June 11, 1921 in New York City to David Cohen, an immigrant from Czechoslovakia, and Gladys Feldt, a native New Yorker. David worked as a shoe salesman, and Gladys cared for their two children: Oscar and Oliver. Oscar describes his parents as extremely intelligent and remembers that his mother spoke beautifully. She could speak to anyone, he recalls, “doctors, lawyers, the woman down the street.” Oscar believes he inherited his parents’ intelligence, but sadly discovered it too late. He feels that he was not given enough guidance or encouragement and didn’t realize his potential until later in life. He learned a lot in grammar school under his strict, old-fashioned Irish teachers, but when he went to high school, “I didn’t learn a damn thing.”

After high school, he began working for an accountant and took business classes at City College of New York, the same school, he adds, that General Powell attended. When World War II broke out, he quit his job and school and reported to the war office. He got a deferment, however, because he was caring for his parents, so they asked him what other skills he had. He then described his love for mechanics and how he was in the habit of building various things at home as a hobby. Oscar believes it was this answer and his “beautifully printed application,” that landed him a job with the army working at Ford Instruments, which built, among other things, naval gunfire control units and later helped to develop computers.

Oscar worked at Ford Instruments until the war ended and then got a job working at Schlater’s Bar near the spot where Rockefeller Plaza now stands. Oscar says that he did everything there—from watching the floor to bartending to being a manager of sorts. In the role of manager, he had all the best musicians come in and play, including Dizzie Gillespie, his personal favorite.

During his years at Schlater’s, Oscar saw all of the “seedy parts of life” and watched “prostitutes, pimps, and muggers” working the poor side of town where the bar was located. The best part of the job, he says, was the “free lunch of salted herring” and “free cigars.” After about five years of this, however, Oscar and his brother, Oliver, deiced to buy a liquor store together. They did not adequately research the neighborhood, though, Oscar says, as they discovered after the fact that there were five other liquor stores near to the one they had bought. Business was extremely slow, except at Christmas time, and they made very little money.

The last straw occurred when the neighboring fish shop was torn down and a colony of huge rats was unearthed. Oscar found himself “eye to eye with rats as big as cats every time I took out the garbage! I couldn’t take it anymore,” he says, and so he and Oliver sold the shop. Besides the rat incidents, he was also becoming more and more disgusted with the cut-throat nature of the business, anyway. He couldn’t stand cheating customers in order to make a profit, especially since he saw so much of that happening all around him.

So for the next year or so, he “knocked around,” doing jobs here and there. He had several bigger opportunities, but he turned them all down, as most of them again involved him “taking advantage of people” in some form or another. The fact that his job prospects seemed to be going nowhere, plus the fact that he was also diagnosed at this time with diabetes, convinced Oscar that he had to search for a new career. He took some courses in lithography to become a film stripper, but realized that his eyesight was too poor to do that kind of work. Instead, he opted for the printing side of things. He worked in a couple of shops, learning the business and working in various positions until he became a pressman. He then got a job at a bigger company, where he joined a printers union, and continued working there as a pressman for sixteen years. It turns out that he was very well-suited to printing and learned many tricks over the years on how to be organized, fast, and efficient. Unfortunately, however, despite the fact that he had found a career he really liked, he had to retire when he was fifty-one due to arthritis in his hands.

Oscar lived in the same apartment he grew up in, having cared for his parents and his father’s cousin until they all passed away. He did a little bit of traveling, taking trips to Philadelphia and the White Mountains, and liked to go out to hear live music. He says he was never a heavy drinker, having seen enough of that during his years at Schlater’s Bar. He smoked until he was seventy and then quit, though he doesn’t think he did much damage because “I never inhaled deeply.” He also spent a lot of time at home listening to his collection of big band records and reading voraciously. He is a avid fan of classic literature, Shakespeare and Cyrano De Bergerac being his favorites. He enjoyed mechanical projects of any nature and did quite a bit of woodworking over the years, as well. Despite the solitary nature of his hobbies, however, he is a very, very social person. He attended the synagogue in his neighborhood in New York for years and had many friends there, but he never married.

His brother, Oliver, however, did get married, and just around the time Oscar was retiring, Oliver decided to move his family to Chicago. Oliver and his wife, Judy, urged Oscar to come, too, but Oscar wanted to remain in New York and stayed there alone for another seventeen years. When Oscar fell and broke a hip, however, in 1989, he was finally convinced by Oliver to move to Chicago so that he would be near family. Oliver helped him to find an apartment in Rogers Park in a building for Jewish senior citizens. Oscar enjoyed his new apartment and his new city, though over the next seven years, his health continued to deteriorate.

In that time, he had two more hip surgeries, cataract surgery, two operations on his intestines, a colostomy, prostrate surgery and eventually had to start dialysis. His doctor calls him “a medical miracle” to still be alive. He was recently hospitalized for various reasons for about six months, after which time his doctor recommended nursing home placement. Knowing that he could no longer care for himself, Oscar agreed. Before he was discharged, Oliver and his daughter, Pam, helped to find a place for him in a Bohemian Home on the northwest side, where he is making a smooth adjustment.

Despite all of his physical ailments, Oscar’s mind is crisp and sharp. He loves words and loves conversation, but despises small talk. He craves in-depth, intellectual conversations, and like his mother, Gladys, can speak on any subject—from the latest news, to Eleanor Roosevelt’s abilities to run the country during the Depression, to Shakespeare, to the national debt. He calls himself a “chain thinker” because “one thought leads to another and another.” Oscar credits his vast knowledge to reading every day on the bus back and forth to work, which, he says, was his “real education.” Reading, he says, “is the secret to education and the secret to writing.”

Politically, Oscar describes himself as a liberal and doesn’t believe the current thinking that today’s problems are the result of problems in the family. He believes that society’s problems are caused by poor educations and the lack of discipline in today’s youth. He feels that “too much freedom is bad.” On the other hand, he thinks minds can become closed with “too many rules and regulations. They become warped somehow.” People, he says, “are only interested in following an instruction book at work and have no room for initiative or invention.”

Despite these somewhat depressing theories, Oscar is not a bitter, negative, or cynical man in any way. He says, “Some people come out crying. I was born laughing.” He says that throughout his life, he was prone to worry, but he tried very hard to control it. He handled stressful situations by “fumbling through them.” He once read that the secret to happiness is to “keep laughing and keep in a good humor,” a philosophy he whole-heartedly adopted. Indeed, Oscar is always laughing and has a wonderful sense of humor. He is aggravated when people “blame God for everything.” His theory is that “man shares 50/50 with God in ruling this world, and if something gets screwed up, it’s not God’s fault.” Oscar is a delightful, charming man who loves to engage with all around him.

(Originally written: July 1996)

If you liked this true story about the past, check out Michelle’s historical fiction/mystery series, set in the 1930s in Chicago:

The post “Rats as Big as Cats!” and Other Stories from the Wonderfully Philosophic Oscar S. Cohen appeared first on Michelle Cox Author.