Gennaro Cuofano's Blog, page 141

November 16, 2021

Google Graveyard: The Top Google Failed Products

Google is certainly the world’s greatest tech giant, with products such as YouTube, Gmail, Chrome, and Google Search synonymous with the internet. But this does not mean the company is immune to failure. Following is a look at just a few of the company’s many failed products.

Google PlusGoogle Plus is one of the company’s more high-profile failures. The social media platform emerged at a time when Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Tumblr were already rather popular. Nevertheless, the platform saw 90 million users within a year of launch.

So, what went wrong?

For one, the circle system used by Google Plus was complex and far from user-friendly. The process of creating separate circles for family and friends did not appeal to most users who wanted a simpler solution.

Google also had to deal with the fallout from security flaws, discovering in late 2018 that the personal data from 52.5 million user accounts had been leaking for at least three years. A Google Plus app was also ignored for the most part, with the company only developing an app after it became clear that Facebook and Twitter were using mobile to their advantage.

By that stage, it was too late. Google Plus was finally shut down in April 2019.

Google Web AcceleratorGoogle Web Accelerator was launched in 2005 to speed up page load times on a user’s computer.

The software was riddled with bugs from the outset, preventing YouTube videos from playing and embedding sensitive personal information in page requests. Google Web Accelerator also tended to retrieve unwanted webpage content and killed webmail sessions as soon as the user logged in.

Google ceased providing support for the software in January 2008.

Google VideoBefore Google acquired YouTube for $1.65 billion in 2006, the company released its own video platform called Google Video.

Ultimately, Google Video was unable to attract users from YouTube which was starting to gather momentum during the mid-2000s. What’s more, Google Video was a very basic video player that didn’t solve a user problem.

For a large company with significant resources, it was simply easier for Google to acquire YouTube and shut down its own platform.

Google AnswersGoogle Answers allowed users to pay a researcher to answer a question they had, with Google taking a percentage of the fee.

Though the fee was typically around $2.50, platforms such as Yahoo! Answers and Quora meant users could find the information for free elsewhere. Interestingly, Google Answers was also competing against Google’s own free search engine.

The service was closed down after approximately 4.5 years.

KnolKnol, an arbitrary term denoting a “unit of knowledge”, was Google’s response to Wikipedia.

Knol was supposed to feature user-generated articles on a variety of topics and even used the same font as Wikipedia. However, the platform failed to gain traction and was shut down in 2012.

While Google recognized the importance of creating an accessible knowledge repository, it did not understand the community aspect that made Wikipedia a success. Contributors to Knol who wanted to make edits were at the mercy of the so-called “expert” who wrote the article. This resulted in users uploading duplicate articles instead of trying to improve existing pieces – a fundamental strength of Wikipedia.

Google also allowed article submitters to earn money through their content through advertising. Inevitably, this attracted users with nefarious intentions to the platform.

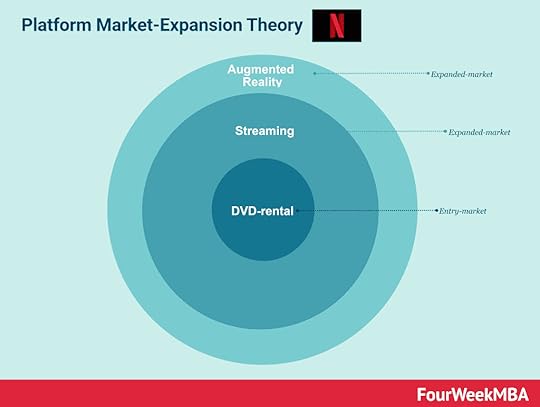

Key takeaways:Google’s most successful products are synonymous with the internet. But the company has certainly had its fair share of failures. The social media network Google Plus is perhaps the most significant.Google Video was another failure because it did not solve an identified user problem. Google Answers was shut down because it competed with free question-answer services such as Yahoo! Answers and Google’s own search engine.Knol was a Wikipedia-esque knowledge site that also failed to gain traction. In developing Knol, Google did not understand the community aspect of Wikipedia that made it so successful.Visual Concepts Related To Google Business Model Google is a platform, and a tech media company running an attention-based business model. As of 2020, Alphabet’s Google generated over $182 billion in revenues. Almost $147 billion came from Google Advertising products (Google Search, YouTube Ads, and Network Members sites). They were followed by over $21 billion in other revenues (comprising Google Play, Pixel phones, and YouTube Premium), followed by Google Cloud, which generated over $13 billion in 2020.

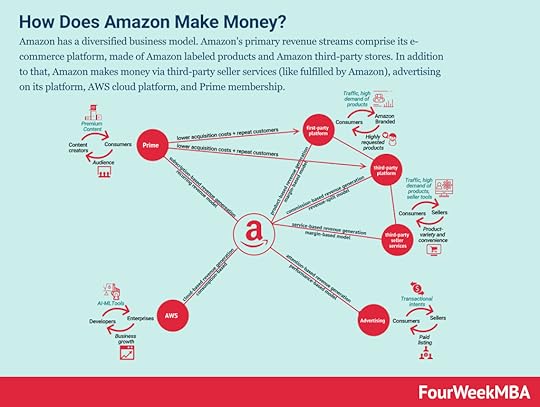

Google is a platform, and a tech media company running an attention-based business model. As of 2020, Alphabet’s Google generated over $182 billion in revenues. Almost $147 billion came from Google Advertising products (Google Search, YouTube Ads, and Network Members sites). They were followed by over $21 billion in other revenues (comprising Google Play, Pixel phones, and YouTube Premium), followed by Google Cloud, which generated over $13 billion in 2020. In an asymmetric business model, the organization doesn’t monetize the user directly, but it leverages the data users provide coupled with technology, thus having a key customer pay to sustain the core asset. For example, Google makes money by leveraging users’ data, combined with its algorithms sold to advertisers for visibility. This is how attention merchants make monetize their business models.

In an asymmetric business model, the organization doesn’t monetize the user directly, but it leverages the data users provide coupled with technology, thus having a key customer pay to sustain the core asset. For example, Google makes money by leveraging users’ data, combined with its algorithms sold to advertisers for visibility. This is how attention merchants make monetize their business models.  DuckDuckGo is a search engine that prioritizes privacy. Thus it throws your data away as a search is performed. Indeed, it simply uses keywords and geodata from the users (if shared on the fly). In addition, the search engine is monetized via affiliate links. Thus DuckDuckGo’s business model proposes an alternative to Google’s business model.

DuckDuckGo is a search engine that prioritizes privacy. Thus it throws your data away as a search is performed. Indeed, it simply uses keywords and geodata from the users (if shared on the fly). In addition, the search engine is monetized via affiliate links. Thus DuckDuckGo’s business model proposes an alternative to Google’s business model.  While Google (now Alphabet) has been born as a search engine, it is now a diversified company, even though its core business remains search, as most of its revenues still come from Google, the search engine, and YouTube, the “video engine.” However, as a tech giant, which business is primarily based on advertising, the company does compete with Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft (with Bing), and Amazon (with e-commerce search and its advertising machine).

While Google (now Alphabet) has been born as a search engine, it is now a diversified company, even though its core business remains search, as most of its revenues still come from Google, the search engine, and YouTube, the “video engine.” However, as a tech giant, which business is primarily based on advertising, the company does compete with Facebook, Twitter, Microsoft (with Bing), and Amazon (with e-commerce search and its advertising machine).  Google and Amazon are fighting for dominance between e-commerce and advertising. Where Google has a monopoly in the search market. Amazon might gain a monopoly in product searches. In 2020, Google opened its Google Shopping for free to contrast Amazon dominance on e-commerce and prevent Amazon from taking more space in the digital advertising industry, the core business fo Google.

Google and Amazon are fighting for dominance between e-commerce and advertising. Where Google has a monopoly in the search market. Amazon might gain a monopoly in product searches. In 2020, Google opened its Google Shopping for free to contrast Amazon dominance on e-commerce and prevent Amazon from taking more space in the digital advertising industry, the core business fo Google. In an asymmetric business model, the organization doesn’t monetize the user directly, but it leverages the data users provide coupled with technology, thus have a key customer pay to sustain the core asset. For example, Google makes money by leveraging users’ data, combined with its algorithms sold to advertisers for visibility.

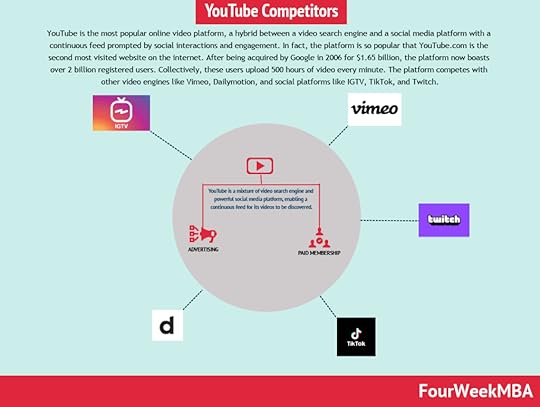

In an asymmetric business model, the organization doesn’t monetize the user directly, but it leverages the data users provide coupled with technology, thus have a key customer pay to sustain the core asset. For example, Google makes money by leveraging users’ data, combined with its algorithms sold to advertisers for visibility.  YouTube is the most popular online video platform, a hybrid between a video search engine and a social media platform with a continuous feed prompted by social interactions and engagement. In fact, the platform is so popular that YouTube.com is the second most visited website on the internet. After being acquired by Google in 2006 for $1.65 billion, the platform now boasts over 2 billion registered users. Collectively, these users upload 500 hours of video every minute. The platform competes with other video engines like Vimeo, Dailymotion, and social platforms like IGTV, TikTok, and Twitch.

YouTube is the most popular online video platform, a hybrid between a video search engine and a social media platform with a continuous feed prompted by social interactions and engagement. In fact, the platform is so popular that YouTube.com is the second most visited website on the internet. After being acquired by Google in 2006 for $1.65 billion, the platform now boasts over 2 billion registered users. Collectively, these users upload 500 hours of video every minute. The platform competes with other video engines like Vimeo, Dailymotion, and social platforms like IGTV, TikTok, and Twitch.Read Also: Google History, Google SWOT, Google Organizational Structure, How Does YouTube Make Money, How To Use Google Sheets, Google Competitors.

Read next:

The Power of Google Business Model in a NutshellHow Does DuckDuckGo Make Money? DuckDuckGo Business Model ExplainedHow Amazon Makes Money: Amazon Business Model in a NutshellHow Does Netflix Make Money? Netflix Business Model ExplainedHow Does Spotify Make Money? Spotify Business Model In A NutshellDuckDuckGo: The [Former] Solopreneur That Is Beating Google at Its GameHow Does Facebook Make Money? Facebook Hidden Revenue Business Model ExplainedMain Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsTech Business ModelThe post Google Graveyard: The Top Google Failed Products appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

November 15, 2021

How Does Coursera Make Money? The Coursera Business Model In A Nutshell

Coursera is an American massive open online course (MOOC) provider founded by Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller in 2012. Coursera revenue is categorized according to consumer, enterprise, and degrees. The consumer category accounts for the majority of revenue with multiple studies and course options for individual students looking to upskill.

History of Coursera The Coursera Timeline, from its inception to its IPO (image Source: Coursera prospectus).

The Coursera Timeline, from its inception to its IPO (image Source: Coursera prospectus).Coursera is an American massive open online course (MOOC) provider founded by Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller in 2012.

Before launching Coursera, both Ng and Koller were Stanford University computer science professors with a mission to bring high-quality education to the masses. The idea for the company came after Ng decided to offer a version of his popular machine learning class online. Ng himself was inspired by Udacity founders Sebastian Thurn and Peter Norvig, who launched their first course on artificial intelligence in 2011.

To ensure the class would be ready for the start of the semester, Ng hired three freshman interns to develop the platform and course content. The group expected around 20,000 people to sign up for the class once it was released. However, over 100,000 signed up.

At some point, Ng partnered with friend Daphne Koller – who was also interested in online education and alternative teaching methods. The pair quickly realized they wanted to scale their idea, eventually deciding to leave Stanford and establish a for-profit business backed by venture capital funding. The start-up raised $16 million with a couple more million dollars contributed by university partners. The three freshmen who initially developed the platform were also hired as paid employees.

Coursera began partnering with high-profile educational institutions such as Princeton, Stanford, and the University of Pennsylvania. Over the years, the company would continue this tradition and attract more students in the process. COVID-19 induced lockdowns also contributed to growth as people used their extra free time to upskill or acquire new knowledge for the sake of it. By the end of 2020, the platform boasted 77 million users.

In February 2021, the company received B Corp certification. This means Coursera has a legal duty to not only its shareholders but also to making a positive impact on society.

Today, Coursera partners with more than 200 universities and companies around the world. Each partnership allows the individual to partake in learning that is flexible, affordable, and job-relevant.

Coursera mission, vision and core values The Coursera Purpose Statement (Image Source: Coursera prospectus).

The Coursera Purpose Statement (Image Source: Coursera prospectus).Coursera’s mission is to “provide universal access to world-class learning so that anyone, anywhere has the power to transform their life through learning.”

Coursera’s core belief is “that education is the source of human progress.” Its vision is accomplished by building up a global platform connecting learners.

As the company highlighted:

The current system of higher education faces inherent challenges. The predominantly classroom-based model may not be able to keep pace with the rapidly emerging skills required to succeed in today’s workforce. While serving certain learners well, the in-person experience may fail to meet the needs of learners in more remote areas and non-traditional learners who need access to education and upskilling the most, both domestically and internationally. Lastly, the cost of education has grown considerably. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, student loan debt in the United States was the second largest component of household debt at $1.55 trillion as of September 30, 2020, creating further headwinds for individuals navigating their careers and personal lives.

Below are some KPIs.

Coursera KPIs as per its financial prospectus.Coursera revenue generation

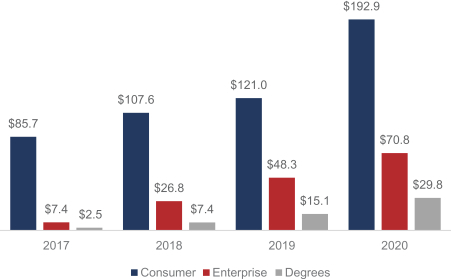

Coursera KPIs as per its financial prospectus.Coursera revenue generation The company generated over $293 million in 2020 and over $66 million in net losses. As Coursera tries to scale its platform, its cost of revenues (money shared with its partners which provide the courses’ materials) and sales and marketing expenses make up most of its costs to run the business.

The company generated over $293 million in 2020 and over $66 million in net losses. As Coursera tries to scale its platform, its cost of revenues (money shared with its partners which provide the courses’ materials) and sales and marketing expenses make up most of its costs to run the business.  Some of the Coursera key performance indicators. The platform had over 76 million students in 2020, it had released 11,900 degrees by 2020, of which it recorded 387 Enterprise Customers. Of the total revenues, about 65% came from the consumer segment, and more than 20% came from the enterprise segment.

Some of the Coursera key performance indicators. The platform had over 76 million students in 2020, it had released 11,900 degrees by 2020, of which it recorded 387 Enterprise Customers. Of the total revenues, about 65% came from the consumer segment, and more than 20% came from the enterprise segment. In general, Coursera works on a freemium business model. Students can take courses for free but must pay if they require official accreditation.

Coursera has multiple revenue generation strategies, split broadly into three segments: consumer, enterprise, and degrees.

Consumer

Consumer

The consumer segment covers payments and subscriptions made directly by students. This is by far the most significant source of revenue for the company, amounting to $192.9 million in 2020.

Individual students have several options here:

Signature Track – for those wishing to earn an official certificate of completion upon completing a free course. Coursera charges between $30 and $100, depending on the course topic.Specializations – this option is essentially a bundle of a few different courses designed to help students deepen their knowledge in a specific area. Students are charged monthly, with prices starting at $39.Professional Certificates – a longer-term commitment of 1-6 months enabling students to gain new knowledge and launch their careers. Some of the available topics include marketing analytics, project management, and social media marketing. Again, prices start at $39/month.MasterTrack® Certificates – featuring 4-7 month learning modules designed to earn credit toward a university degree. These certificates focus on real-world projects that have practical applications. Topics include data analytics, social work, and health informatics. Prices start at $2,000.Coursera Plus – an all-in-one solution featuring unlimited access to 3,000 courses, Specialisations, and Professional Certificates. Once the 30-day free trial has ended, students must pay $395 annually.EnterpriseThe enterprise segment incorporates business and government clients wishing to train teams of employees. Coursera also includes universities offering online courses to students in this segment.

Some of the major clients to utilize the Coursera For Business service include L’Oréal, Danone, General Electric, Tata, and Proctor & Gamble. For teams and smaller organizations, the cost is $399 per user per year.

For larger companies, prices are tailored to the size of the organization and are available on request. Its enterprise offering comprises:

Coursera for Business: seat license subscription through the Enterprise Plan where small and larger businesses can use to train their teams. Coursera for Campus a subscription to college and university customers with either a fixed number of licenses or enrollments per campus or a fixed contract with unlimited learners. Coursera for Government: a fixed subscription per licensed user per year. DegreesLastly, the degrees section deals with universities that are offering complete Bachelor’s or Master’s degrees online.

Degrees are offered in a range of disciplines, including Business, Computer Science, Data Science, Public Health, and Engineering.

Prices for online degrees are substantially less than the equivalent in-person degrees because overhead costs are lower. Most degrees can be completed in 2-4 years and prices start at $9,000.

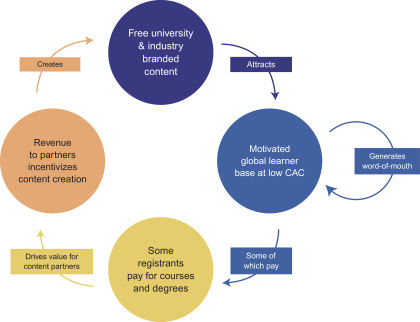

How Coursera business model worksCoursera’s business model is based on an educational platform enabling educators, learners, and institutions to connect through a broad range of learning offerings: Guided Projects, courses, Specializations, certificates, and degrees. Its go-to-market strategy is based on freemium offerings.

The large registered learner base makes it easy to acquire users that can be converted into paying consumers or enterprise accounts. Indeed the consumer learners represent the “top-of-the-funnel” or the main source of leads that can be converted in Enterprise or degree offerings.

In fact, in 2020, about 50% of new degrees were generated by registered free Coursera users and 30% of Coursera Enterprise leads were also sourced from the Enterprise platform.

The Coursera consumer flywheel starts with a platform that provides free, high-quality content with an efficient acquisition model. The company estimated in 2020 the student acquisition cost was below $2000 per student’s degree.

The Coursera consumer flywheel starts with a platform that provides free, high-quality content with an efficient acquisition model. The company estimated in 2020 the student acquisition cost was below $2000 per student’s degree. As noted in the introduction, Coursera partners with leading educational institutions to offer online courses to students.

These courses are pre-recorded video lectures the student can watch on a set schedule or at a more convenient time. To facilitate learning, each course incorporates homework, assignments, exams, and a discussion forum. Importantly, courses are taught by actual university professors.

Interested students need to sign up for a free account and choose the subjects they are interested in studying. Then, they must select the courses they want to take and decide whether they would like to receive accreditation for their successful completion.

In recent years, the company has moved away from its massive open online course heritage and toward a model where students pay for stackable, short-course credentials. These credentials take the form of completion certificates which are endorsed by the high-profile universities Coursera partners with. Coursera qualifications are looked upon favorably by employers, despite the company favoring a non-traditional, off-campus approach to higher learning.

Image Source: Coursera prospectus.Who owns Coursera?

Image Source: Coursera prospectus.Who owns Coursera?Below is a look at the ownership structure of Coursera, with the company last releasing data in December 2020:

New Enterprise Associates (18.3%) and Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (9.2%) – venture capital firms.G Squared (15.9%) – a growth-stage venture fund.Northern Trust (7.9%) – a financial services company.Andrew Ng (7.8%) – Coursera co-founder.Jeffrey Maggioncalda (3.5%) – Coursera president and CEO. Key takeaways:Coursera is an American massive open online course (MOOC) provided founded by Andrew Ng and Daphne Koller in 2012. The idea for the company came after Ng noticed the popularity of an online extension to a machine learning course he was teaching at Stanford University.Coursera revenue is categorized according to consumer, enterprise, and degrees. The consumer category accounts for the majority of revenue with multiple study and course options for individual students looking to upskill.Coursera courses are taught by actual professors from top universities that endorse the completion certificates awarded to students. In recent years, the company has moved away from its massive open online course focus toward stackable, short-course credentials.Related EdTech Business Models Duolingo is an EdTech platform leveraging gamification to enable millions of users to learn languages. Duolingo leverages a hybrid between ad-supported and freemium models. Indeed, the free app makes money through advertising. Free users are also channeled into premium subscriptions with an ad-free experience and more features.

Duolingo is an EdTech platform leveraging gamification to enable millions of users to learn languages. Duolingo leverages a hybrid between ad-supported and freemium models. Indeed, the free app makes money through advertising. Free users are also channeled into premium subscriptions with an ad-free experience and more features. Khan Academy is an EdTech non-profit organization whose mission is “to provide a free, world-class education to anyone, anywhere,” It runs thanks to the sponsors of various donors that keep the platform developing content at scale for its millions of students across the world.

Khan Academy is an EdTech non-profit organization whose mission is “to provide a free, world-class education to anyone, anywhere,” It runs thanks to the sponsors of various donors that keep the platform developing content at scale for its millions of students across the world. Started as an attempt to transform education, MasterClass finds top talents and turn them into instructors. With a straightforward membership model of $180 per year, the streaming online education platform gives access to all its courses and the new releases on the platform. In 2020, it got valued at over $800 million.

Started as an attempt to transform education, MasterClass finds top talents and turn them into instructors. With a straightforward membership model of $180 per year, the streaming online education platform gives access to all its courses and the new releases on the platform. In 2020, it got valued at over $800 million. Udacity is a freemium EdTech platform, offering MOOCs (courses open to anyone for enrolment). Udacity partners up with companies and universities to offer nanodegrees (short-term online education programs focused on specialized skills in computer science). The user either pays a one-time or subscription fee to access one or all courses.

Udacity is a freemium EdTech platform, offering MOOCs (courses open to anyone for enrolment). Udacity partners up with companies and universities to offer nanodegrees (short-term online education programs focused on specialized skills in computer science). The user either pays a one-time or subscription fee to access one or all courses. Udemy is an e-learning platform with two primary parts: the consumer-facing platform (B2C). And the enterprise platform (B2B). Udemy sells courses to anyone on its core marketplace, while it sells Udemy for Business only to B2B/Enterprise accounts. As such, Udemy has two key players: instructors on the marketplace, and business instructors for the B2B platform.

Udemy is an e-learning platform with two primary parts: the consumer-facing platform (B2C). And the enterprise platform (B2B). Udemy sells courses to anyone on its core marketplace, while it sells Udemy for Business only to B2B/Enterprise accounts. As such, Udemy has two key players: instructors on the marketplace, and business instructors for the B2B platform.Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsTech Business ModelsThe post How Does Coursera Make Money? The Coursera Business Model In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

How Does Coupang Make Money? The Coupang Business Model In A Nutshell

Coupang is a South Korean eCommerce company. Coupang makes money by selling consumer items through its desktop and mobile eCommerce platform. The company also collects various fees from its food delivery, video streaming, and advertising services.

History of CoupangCoupang is a South Korean eCommerce company founded by Bom Kim in 2010. Due to its size and market position, Coupang is often referred to as the “Amazon of South Korea”.

The company began as a Groupon-style daily deals business after Kim dropped out of Harvard Business School. However, he quickly pivoted to an auction-based marketplace after noticing the growing influence of eCommerce. Despite crossing $1 billion in sales just three years later, Kim was not convinced that customers loved his business.

He decided to pivot once more, this time reinventing Coupang as an end-to-end shopping platform where the full customer journey was managed from desktop to door. This necessitated that a new logistics business be constructed to delight customers and improve South Korea’s inefficient postal service. Coupang now delivers 99.3% of all orders within 24 hours, with customers able to receive their goods by 7 a.m. if they purchase before midnight the day before.

In recent years, Coupang has expanded into other services. Rocket Wow is a paid subscription service similar to Amazon Prime, with perks such as free or one-day delivery and discounts on certain products. Rocket Fresh is a fresh food delivery service promising similarly rapid delivery, while the restaurant delivery service Coupang Eats and video streaming service Coupang Play are also recent additions.

In March 2021, the company held an IPO on the New York Stock Exchange which valued it at approximately $84.5 billion. One month after entering Japan in June, Coupang launched in Taiwan where established players Uber Eats and Foodpanda are already operating. At the time of writing, Coupang has not divulged further expansion plans. However, the company has been observed hiring for lead operations, retail, and logistics roles in Singapore.

Coupang missionCoupang’s mission is to “create a world where customers wonder: ‘How did I ever live without Coupang?'”

Coupang revenue generation

As an eCommerce retailer, Coupang primarily makes money by selling consumer items online. This includes the sale of third-party goods and private-label items, with the latter resulting in higher margins.

Having said that, Coupang does make money in several other ways. Let’s take a look at them in the following paragraphs.

Rocket JikguRocket Jikgu is a delivery service for South Korean citizens who want to receive overseas orders in less than three days. The service claims to offer 80,000 items from 3,500 global brands.

Most of these brands are those not officially imported into the country and typically include vitamins, cosmetics, and detergent from the United States.

To shorten delivery times, Coupang sources products directly from the manufacturer without involving a third party.

Delivery is free if the total order amount exceeds 29,800 won, equivalent to approximately $25.

Coupang EatsCoupang Eats is a food delivery service offering a wide range of products including meal kits, salads, meat, and ice cream.

The company charges a delivery fee of around 2,000 South Korean won ($1.70) for each order, with no minimum order amount.

Rocket WowAs noted earlier, Rocket Wow is an Amazon Prime-like service offering fast delivery and other perks.

Here, the company charges 2,900 South Korean won ($2.50) each month after a 30-day free trial.

Coupang PlayCoupang Play is an on-demand video streaming service.

The company also charges 2,900 South Korean won per month, but Rocket Wow subscribers can access Coupang Play for free.

AdvertisingCoupang also sells advertising to interested parties. Advertising spots are based on the pay-per-click (PPC) system, so merchants are only charged when the ads are clicked on by a consumer.

Advertising is seen on almost every page of the Coupang website, allowing businesses to access their target audience across various touchpoints. Available formats include category page listings, banners, and even order completion page ads.

How it worksTo order goods online, Coupang users must visit the company website on either desktop or mobile. The latter is the preferred method for most, with mobile applications accounting for 75% of total sales.

Margins on most third-party products are thin, a problem common to many eCommerce retailers. To counteract these thin margins, Coupang is following the lead of Amazon by developing private-label product ranges in high-value segments such as apparel, beauty, and electronics.

In terms of order fulfillment, Coupang can deliver rapidly because it fulfills orders itself. By operating its own distribution and logistics network, it avoids the relatively inefficient practice of sending couriers to third-party stores and restaurants.

The size and reach of this logistics network is impressive, with the company noting that 70% of its customers live within ten minutes of one of its more than 100 distribution centers. What’s more, Coupang’s established logistics network has allowed it to expand into food delivery with relative ease.

Who owns Coupang?Coupang is majority-owned by venture capital and private equity funds with a 54% stake. Institutions comprise 16.3%, while the general public holds 12.4%. Individual insiders, or those that sit on the board or hold other senior management positions, have a 10.3% stake in the company.

In 2018, the company received a $2 billion investment from SoftBank Investment Advisers (UK) Limited, with the venture capital group subsequently taking a 33.1% shareholding.

Some of the other major shareholders include:

Greenoaks Capital Partners LLC (16%).Bom Suk Kim (10%).Maverick Holdings (6.4%).Key takeaways:Coupang is a South Korean eCommerce company founded by Bom Kim in 2010. The company began as a Groupon-style daily deals business after Kim dropped out of Harvard Business School.Coupang makes money by selling consumer items through its desktop and mobile eCommerce platform. The company also collects various fees from its food delivery, video streaming, and advertising services.Coupang can deliver orders rapidly thanks to a logistics network where no South Korean citizen is more than 10 minutes from a fulfillment center. The company is majority-owned by venture capital and private equity funds, with Softbank the largest shareholder at 33%. Related Business Models DoorDash is a platform business model that enables restaurants to set up at no cost delivery operations. At the same time, customers get their food at home and dashers (delivery people) earn some extra money. DoorDash makes money by markup prices through delivery fees, memberships, and advertising for restaurants on the marketplace.

DoorDash is a platform business model that enables restaurants to set up at no cost delivery operations. At the same time, customers get their food at home and dashers (delivery people) earn some extra money. DoorDash makes money by markup prices through delivery fees, memberships, and advertising for restaurants on the marketplace. Glovo is a Spanish on-demand courier service that purchases and delivers products ordered through a mobile app. Founded in 2015 by Oscar Pierre and Sacha Michaud as a way to “uberize” local services. Glovo makes money via delivery fees, mini-supermarkets (fulfillment centers that Glovo operates in partnership with grocery store chains), and dark kitchens (enabling restaurants to increase their capacity).

Glovo is a Spanish on-demand courier service that purchases and delivers products ordered through a mobile app. Founded in 2015 by Oscar Pierre and Sacha Michaud as a way to “uberize” local services. Glovo makes money via delivery fees, mini-supermarkets (fulfillment centers that Glovo operates in partnership with grocery store chains), and dark kitchens (enabling restaurants to increase their capacity). Grubhub is an online and mobile platform for restaurant pick-up and delivery orders. In 2018 the company connected 95,000 takeout restaurants in over 1,700 U.S. cities and London. The Grubhub portfolio of brands like Seamless, LevelUp, Eat24, AllMenus, MenuPages, and Tapingo. The company makes money primarily by charging restaurants a pre-order commission and it generates revenues when diners place an order on its platform. Also, it charges restaurants that use Grubhub delivery services and when diners pay for those services.

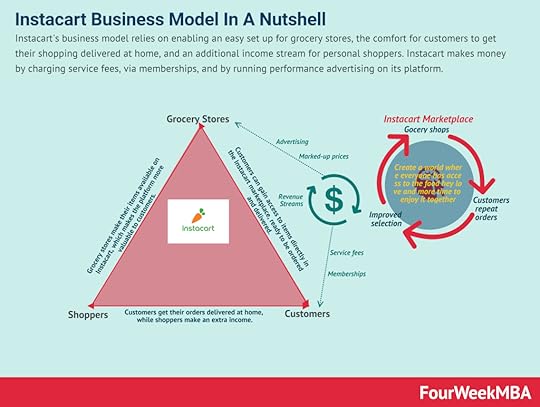

Grubhub is an online and mobile platform for restaurant pick-up and delivery orders. In 2018 the company connected 95,000 takeout restaurants in over 1,700 U.S. cities and London. The Grubhub portfolio of brands like Seamless, LevelUp, Eat24, AllMenus, MenuPages, and Tapingo. The company makes money primarily by charging restaurants a pre-order commission and it generates revenues when diners place an order on its platform. Also, it charges restaurants that use Grubhub delivery services and when diners pay for those services.  Instacart’s business model relies on enabling an easy set up for grocery stores, the comfort for customers to get their shopping delivered at home, and an additional income stream for personal shoppers. Instacart makes money by charging service fees, via memberships, and by running performance advertising on its platform.

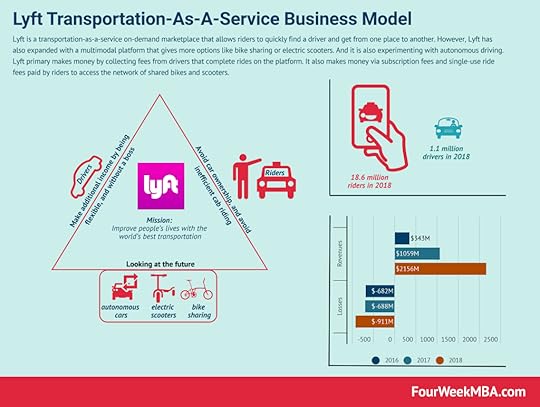

Instacart’s business model relies on enabling an easy set up for grocery stores, the comfort for customers to get their shopping delivered at home, and an additional income stream for personal shoppers. Instacart makes money by charging service fees, via memberships, and by running performance advertising on its platform. Lyft is a transportation-as-a-service marketplace allowing riders to find a driver for a ride. Lyft has also expanded with a multimodal platform that gives more options like bike-sharing or electric scooters. Lyft primary makes money by collecting fees from drivers that complete rides on the platform.

Lyft is a transportation-as-a-service marketplace allowing riders to find a driver for a ride. Lyft has also expanded with a multimodal platform that gives more options like bike-sharing or electric scooters. Lyft primary makes money by collecting fees from drivers that complete rides on the platform. Uber is a is two-sided marketplace, a platform business model that connects drivers and riders, with an interface that has elements of gamification, that makes it easy for two sides to connect and transact. Uber makes money by collecting fees from the platform’s gross bookings.

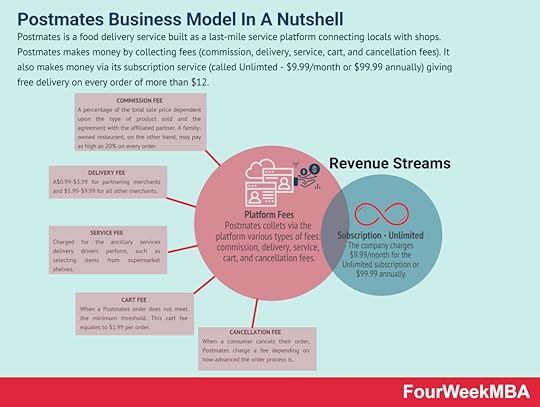

Uber is a is two-sided marketplace, a platform business model that connects drivers and riders, with an interface that has elements of gamification, that makes it easy for two sides to connect and transact. Uber makes money by collecting fees from the platform’s gross bookings. Postmates is a food delivery service built as a last-mile delivery service platform connecting locals with shops. Postmates makes money by collecting fees (commission, delivery, service, cart, and cancellation fees). It also makes money via its subscription service (called Unlimted – $9.99/month or $99.99 annually) giving free delivery on every order of more than $12.

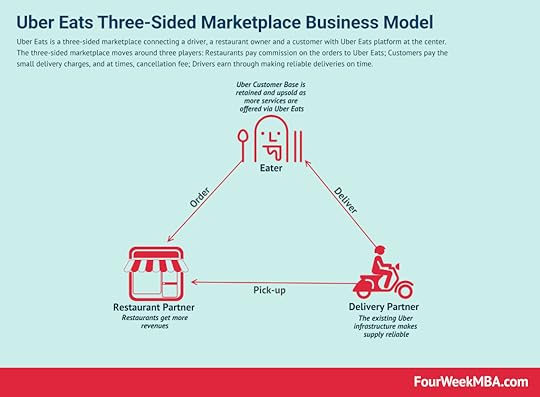

Postmates is a food delivery service built as a last-mile delivery service platform connecting locals with shops. Postmates makes money by collecting fees (commission, delivery, service, cart, and cancellation fees). It also makes money via its subscription service (called Unlimted – $9.99/month or $99.99 annually) giving free delivery on every order of more than $12. Uber Eats is a three-sided marketplace connecting a driver, a restaurant owner and a customer with Uber Eats platform at the center. The three-sided marketplace moves around three players: Restaurants pay commission on the orders to Uber Eats; Customers pay the small delivery charges, and at times, cancellation fee; Drivers earn through making reliable deliveries on time.

Uber Eats is a three-sided marketplace connecting a driver, a restaurant owner and a customer with Uber Eats platform at the center. The three-sided marketplace moves around three players: Restaurants pay commission on the orders to Uber Eats; Customers pay the small delivery charges, and at times, cancellation fee; Drivers earn through making reliable deliveries on time.Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post How Does Coupang Make Money? The Coupang Business Model In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

November 3, 2021

Bigness, Too Big To Scale: How Companies Change With Size

Too big to scale is a phenomenon where a company has passed a threshold that makes it much more fragile to scale. In short, an additional level of scale instead of creating growth efficiency generates at best diseconomies of scale. At worse congestion and collapse.

Understanding the implication of Scale and SizeFor years, Facebook’s founder’s — Mark Zuckerberg– motto has been “move fast and break things.” This motto helped the company scale from a single computer in a dorm room to one of the largest tech companies in the world.

Yet, back in 2017, that motto changed to “Move fast with stable infrastructure.” This is a paradigm shift from both a technical and business standpoint and it might fool you into believing that the decision to change its motto came centrally, from Mark Zuckerberg.

However, the key lesson I want you to bring home is that as Facebook size reached a certain threshold, the company completely transformed. And this transformation was not the consequence of a drafted plan, written down and executed. But instead, it was the consequence of size.

In short, as Facebook grew and scaled, it automatically changed as an organization. If at all, as the Facebook executive team realized that, they had to change its motto to fit this new reality.

Breaking things was no longer an option for Facebook. Indeed, the cost of breaking something at Facebook’s scale was so high (not only for the company but for society) that keeping this mantra would have resulted in the company’s collapse under its own size.

Just like an ant, that turns into an elephant, Facebook had transformed. Scale had changed it all.

Thus, a software bug, that once was not expensive to fix, with billions of interactions through the platform, that same bug would have meant a huge effort from the engineering team to fix it. Together with the reputational and legal risk coming with it.

When that level of scale is achieved, where size makes the company a potential burden to society, the company loses its ability to experiment fast (as each of those experiments carries a too high potential negative cost to society), and it becomes a market monopolist.

Size prevents quick experimentation, also the pace of innovation is significantly slowed down. Therefore, the Too Big To Scale player’s only option is to limit competition in the market, by means of acquisitions, bad business practices (like knock-offs, or copycat products), and lobbying.

As we’ll see here though, not all scale is bad, and scaling to a certain size might actually help the business become more effective.

What scale does to companies?While scale and size might seem two separate things at a first sight. In reality, scale and size move in an infinite loop, that determines a sort of “science of growth.” As we move within complex systems, scale can help that system grow, yet as the system grows it changes, it becomes something new.

Business people that have transformed companies from startups, to scale up, mature, and (in some cases) monopolies know that well.

In his book, Scale, Geoffrey West gives an incredible account of how scale changes things, from physical to more complex things (like cities and companies). Some of the key points of this study highlight how things scale in most cases in a non-linear fashion.

In short, they fall under what we know as power laws. Growth is analyzed as a mechanism between incoming energy + the energy required for the organism’s maintenance (Geoffrey West divides it into repair and replacement) + new growth.

From this simple equation, we can determine how growth looks like.

Thus, the metabolic rate (or how the metabolic energy is distributed across maintenance of existing cells/physical structure and the creation of new ones) can increase sublinearly or superlinearly.

This will trace the difference between sublinear (thus bounded) and superlinear (unbounded) growth.

Bounded vs unbounded growthIn biology, as organisms increase their size, something interesting happens. As a reminder, growth in biological terms can be seen as the difference between metabolism (the energy generated by the organism) and maintenance (that needed for regenerating).

As size scales, metabolism scales sublinearly. It, therefore, slows down, and it’s not able to pick up with the energy needed for maintenance, thus creating over time (as size increases) a situation of growth stagnation.

In the opposite scenario, where metabolism scales superlinearly, it’s able to pick up more quickly with the maintenance needed, and therefore has the potential to keep growing, as size increases (one of such examples are cities).

In a scenario of unbounded growth, the underlying mechanism is superlinear scaling. In short, the underlying organism that scales superlinearly, could, in theory, keep growing forever.

These examples that Geoffrey West gives in the book “Scale” are enlightening. In short, according to the research of the book, the metabolic rate of companies is stuck in the middle, where they do grow quickly as they first scale. This is why younger companies – if investing back their resources into the business can quickly gain traction.

There is a stage in which, a large, mature organization stops growing altogether.

As we’ve seen companies do grow quickly as they are young, and small in size. Yet, as they become large and mature, there is a point in which growth might stop altogether.

Size, fragility and decentralizationLet’s plug another piece of the puzzle here. In his book series, Incerto, Nassim Nicholas Taleb gives us another important piece.

In a lecture, on “Small is Beautiful” Taleb highlighted:

We use fragility theory to show the effect of size and response to uncertainty, how distributed decision-making creates more apparent volatility, but ensures long term survival of a system. Simply, economies of scale are more than offset by stochastic diseconomies from shocks and there is such a thing as a “sweet spot” in optimal size. We show how city-states fare better than large states, how mice and small species are more robust than elephants, and how the canton mechanism can potentially solve Near Eastern problems.

As Taleb also highlighted in a tweet “What works on a small scale almost NEVER expands to large scale.”

How monopolies negatively affect marketsConventional economics attributes to economies of scale, thus size, the ability of companies to become so efficient to build so-called “moats.” Or along with lasting economic advantage. This belief has led to the creation in many industries (since the 1980s) of massive monopolies, that do look like states.

However, the reason why monopolies developed is the opposite. They developed because market concentrations were not only allowed, but also favored in many industries. Yet, the overall effect of monopolies on marketplaces lead to:

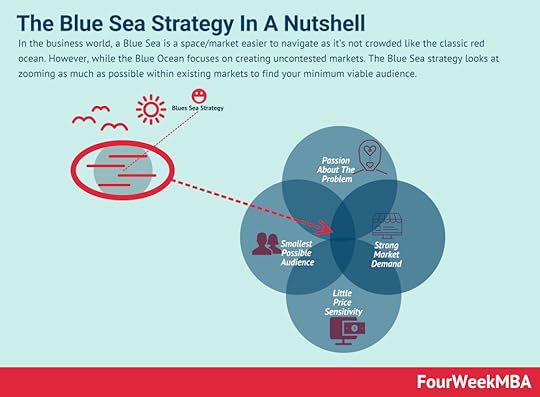

Reduced competition.Reduced innovation. Negative externalities.System fragility. Higher overall costs for consumers.How do you scale without turning into a monopoly? Place bets.Create independent spin offs: do not try to align cultures across companiesIf you stay small keep control, if you become large flat up the organization: we’re used to the opposite scenario. Where companies that are big are pretty much beurocratic, centralized and follow a gerarchic decision-making structure. Instead, while it’s fine to keep tight control as the company is small, after a certain size it should be decentralized. How do you enter a market dominated by a monopoly?What might seem a strength of the monopolist, that of encompassing a whole market. It’s in reality a weakness, as it creates the opportunity for new companies to create value with a Blue Sea Approach. And we’ll see how the Strategy Lever Framework can be used to enter a market dominated by a monopoly.

Read: Business Scaling, Developing A Business Strategy.

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyMarketing StrategyBusiness Model InnovationPlatform Business ModelsNetwork Effects In A NutshellDigital Business ModelsThe post Bigness, Too Big To Scale: How Companies Change With Size appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

Why Did Segway Fail? What Happened To Segway

The Segway is a two-wheeled, self-balancing personal transporter invented by Dean Kamen and launched in 2001 as the Segway PT.

The transporter arrived on the scene with much fanfare, with consumers curious and eager to ride a device that looked like it belonged in a sci-fi movie. Upon its release, Kamen believed “the Segway HT will do for walking, what the calculator did for pad and pencil. Get there quicker. You’ll go further.” This, he hoped, would also help the two-wheeled transporter revolutionize the way cities were laid out and how people moved through them.

Just six years later, the PT had achieved only 1% of its sales target. Kamen hoped to sell half a million units per year, but after six years had sold a mere 30,000. The company was later acquired by Ninebot, Inc., with the Chinese robotics start-up announcing it would discontinue production in June 2020.

What went wrong?

Consumer novelty and safety regulationsSteve Jobs famously warned Kamen the Segway’s image could be ruined by a single rider falling off and hurting themselves.

In 2003, press photographers captured President George W. Bush dismounting from his Segway during a family vacation. Piers Morgan, a notable British journalist, also had a fall in 2007 and broke three ribs in the process.

In June 2010, Segway company owner James Heselden died after riding his Segway off a cliff and into a river.

It’s important to note that the Segway was not an inherently dangerous form of transportation. Instead, many who were accustomed to driving cars were simply unaware of the safety gear required to operate a two-wheeled vehicle. Most barely wore a helmet, let alone the protective gear commonly seen on motorcycle riders, for example.

Eventually, transport authorities did step in and enforce certain rules for Segway use.

Poor pricing strategySegway RTs were initially priced at $5,000, a hefty price to pay to avoid walking and equivalent to buying a reliable used car.

Some suggest the company should have offered the Segway on a pay-per-use basis. However, this would have been difficult since smartphones and smartphone apps had yet to achieve critical mass.

ImpracticalityTo some extent, the Segway was impractical. It was small enough to fit inside an elevator, but its 100-pound bulk made it impractical for buildings with stairs.

It also occupied a somewhat awkward gap in the personal transportation market. With most cities designed for pedestrians and large vehicles but nothing in between, there was no infrastructure to support the Segway as a form of mass transportation.

In many countries, it was banned from sidewalks and roads because authorities didn’t know how to classify it.

Early adopters were also called fat and lazy and felt they should have been walking instead. Many consumers considered the Segway to be a device that invited mockery, which no doubt impacted sales and public perception.

Poor market researchLike many products that promise to revolutionize the world, the company ended up releasing an invention and not an innovation.

The RT was kept a secret until launch and there was little if any consideration given to user feedback and testing.

History will also show that the inventors failed to identify a viable target market. This point is related to impracticality and Segway’s failure to identify a compelling reason for a consumer to shell out $5,000.

CompetitionIn 2017, electric scooter companies such as Bird and Lime effectively sealed the fate of the Segway.

The scooters, which are controlled by an app, are a much cheaper (and somewhat safer) form of personal transportation in cities.

Read The Business Failure Book

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post Why Did Segway Fail? What Happened To Segway appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

What Happened To Google Glass? How Google Glass Set The Stage For The AR Revolution

Google Glass is a brand of smart glasses with an optical, head-mounted display. Google developed the glasses with the intent to produce a ubiquitous computer allowing the wearer to communicate with the internet via voice commands.

Prototype Google Glass smart glasses were launched in April 2013 for the princely sum of $1,500. Almost immediately, they attracted criticism from consumers who had concerns over their privacy, safety, and cost.

Just two years later, Google announced it would be ceasing production of the consumer version of the glasses. The company then pivoted to the business sector and launched Glass Enterprise Edition for certain workplaces such as factories and surgeries.

Why did the consumer version fail so spectacularly? Read on to find out.

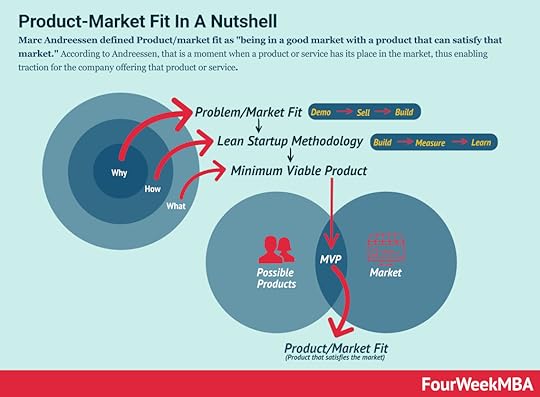

Product-market fit Marc Andreessen defined Product/market fit as “being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.” According to Andreessen, that is a moment when a product or service has its place in the market, thus enabling traction for the company offering that product or service.

Marc Andreessen defined Product/market fit as “being in a good market with a product that can satisfy that market.” According to Andreessen, that is a moment when a product or service has its place in the market, thus enabling traction for the company offering that product or service.Google Glass failed as a product because its inventors neglected to do the proper research on its potential users and the market more generally. Instead of developing a product that would solve user problems, they believed the glasses would sell on hype and revolutionary technology alone.

Poor product development was exposed by the early adopters who could not identify any meaningful benefits to wearing the glasses. What’s more, the glasses were not technologically advanced enough to warrant regular use and Google had not determined whether they were comfortable to wear for long periods.

CompetitionGoogle had lofty ambitions to augment reality with a touchpad, camera, and LCD or LED display. In truth, however, all the company did was supplement reality.

Ultimately, the sunglasses had a limited battery life of between three to five hours. They were also competing with smart televisions, watches, and speakers that had faster processors, larger capacities, and better cameras.

Stigma and negative publicityGoogle Glass attracted significant criticism after it was discovered wearers could film others covertly.

Some bars and restaurants banned wearers from entry, with the term “Glasshole” coined around the same time. Google then released a statement instructing users to respect the privacy of others and not be creepy or rude, but the damage had been done.

The timing of the negative publicity was also unfortunate since there was also rising distrust around the power of big tech companies at the time.

CostEven the prototype version of the glasses retailed for $1,500 – equivalent to the price of a well-equipped desktop computer.

The high cost of the glasses was exacerbated by the fact that they didn’t perform any function especially well. As a result, those who could afford them were content purchasing a more affordable smartphone without the associated stigma of owning it.

TimingWhile as a company you can innovate, and create new markets. Oftentimes, technologies proceed with the development of complementary innovations. At the time, AR might have been too early to be accepted, given the strong transition from desktop to mobile. In that phase though, mobile won.

Setting the stage for the AR revolutionAugmented reality and virtual reality are taking the center stage, in what has been defined as “Metaverse.”

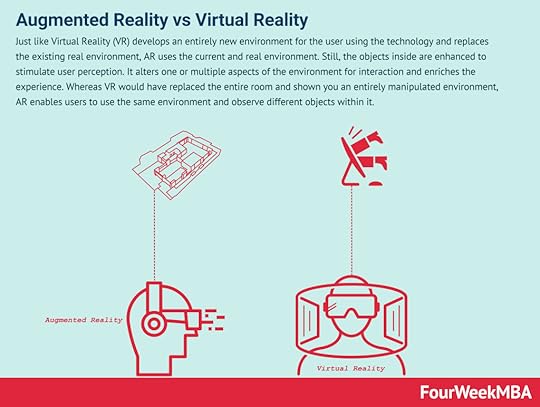

Just like Virtual Reality (VR) develops an entirely new environment for the user using the technology and replaces the existing real environment, AR uses the current and real environment. Still, the objects inside are enhanced to stimulate user perception. It alters one or multiple aspects of the environment for interaction and enriches the experience. Whereas VR would have replaced the entire room and shown you an entirely manipulated environment, AR enables users to use the same environment and observe different objects within it.

Just like Virtual Reality (VR) develops an entirely new environment for the user using the technology and replaces the existing real environment, AR uses the current and real environment. Still, the objects inside are enhanced to stimulate user perception. It alters one or multiple aspects of the environment for interaction and enriches the experience. Whereas VR would have replaced the entire room and shown you an entirely manipulated environment, AR enables users to use the same environment and observe different objects within it.Today these technologies and products might become the next frontier. As companies like Apple dominated the mobile industry. Who’ll be able to tame the next wave will also ride a very large market.

Read The Business Failure Book

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post What Happened To Google Glass? How Google Glass Set The Stage For The AR Revolution appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

What Happened To Digg? How Digg Failure Brought To Reddit’s Success

Digg is an American news aggregator website founded by Jay Adelson and Kevin Rose in 2004.

Digg was once an extremely successful social platform that disrupted the news industry with a curated front page of popular and shareable web content. Users could vote such content up or down, which Digg called digging and burying respectively.

The platform reached peak popularity between 2006 and 2010, with the site attracting close to 200 million unique visits per year. Independent websites mentioned on the Digg homepage frequently crashed due to the sudden influx of traffic, a phenomenon called the “Digg effect”.

In 2012, however, after a total of 350 million upvotes, the site announced it would be acquired by technology investment company Betaworks. The purchase price of $500,000 was a fraction of the $160 million Digg was thought to be worth during its heyday.

Let’s take a look at how Digg fell from grace.

The emergence of competitorsThe Digg button, which allowed users to submit a site to Digg, suddenly had competition. The Facebook Like button was launched in April 2010 and could be found on 350,000 sites just five months later.

Around the same time, Digg had to deal with the rapid emergence of social news site Reddit and to a lesser extent, Twitter.

The impact of this extra competition was exacerbated by a Google Algorithm update that same year, which made Digg links less valuable in search result rankings.

User experience issuesFaced with increased competition and declining traffic, Digg decided to act with a now-infamous site redesign in August 2010.

The new design was widely criticized by users because it removed many popular features, including the ability to bury posts, save favorites, post videos, and sort by subcategory. What’s more, the platform became buggy, and users were frustrated that they couldn’t communicate with other users directly. Perhaps most damaging of all, the updates were implemented without any regard to user feedback.

This alienated Digg’s user base and caused mass migration to Reddit in particular, which maintained user trust by remaining consistent throughout.

Platform abuseDigg’s reputation as a democratic news service where everyone could submit links and vote quickly devolved into an oligarchy of power users.

Each of these power users had a disproportionate influence on votes because of their large and devoted following. Whenever they submitted a link to Digg, their followers would game the system by populating the front page with their content.

Investor pressure to make Digg profitable also resulted in the essence of the platform being abused. The platform removed popular features to copy the business model of more profitable websites. Decision-makers also changed the ranking algorithm when the site was redesigned so that corporate-sponsored articles were published on the home page.

Sale and relaunchDigg was sold in three separate parts during July 2012. The Digg Brand, website, and technology were sold to Betaworks, while 15 staff transferred to The Washington Post. Professional network LinkedIn also purchased multiple patents for approximately $4 million.

Betaworks relaunched Digg in 2012 with many of its original features reinstated. However, the platform never recovered as competitors such as Reddit took most of the market share.

Six years later, Digg was acquired by advertising company BuySellAds.com for an undisclosed amount.

How Digg failure set the stage fro Reddit’s successAs Digg failed, Reddit took off. The platform has become among the most popular social network of our times, thanks to the ability to have subcommunities create their own digital environments so that users could freely express themselves.

Reddit is a social news and discussion website that also rates web content. The platform was created in 2005 after founders Alexis Ohanian and Steve Huffman met venture capitalist Paul Graham and pitched the company as the “front page of the internet.” Reddit makes money primarily via advertising. It also offers premium membership plans.

Reddit is a social news and discussion website that also rates web content. The platform was created in 2005 after founders Alexis Ohanian and Steve Huffman met venture capitalist Paul Graham and pitched the company as the “front page of the internet.” Reddit makes money primarily via advertising. It also offers premium membership plans.  Some people find marketing on Reddit very outdated and obsolete, yet where Facebook and Instagram are today’s traditional marketing channels, Reddit has the nature of being unconventional amongst them. Reddit can be a great viral channel to cheaply amplify your brand and fill the top of the funnel.

Some people find marketing on Reddit very outdated and obsolete, yet where Facebook and Instagram are today’s traditional marketing channels, Reddit has the nature of being unconventional amongst them. Reddit can be a great viral channel to cheaply amplify your brand and fill the top of the funnel.Read The Business Failure Book

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyBusiness DevelopmentDigital Business ModelsDistribution ChannelsMarketing StrategyPlatform Business ModelsRevenue ModelsTech Business ModelsBlockchain Business Models FrameworkThe post What Happened To Digg? How Digg Failure Brought To Reddit’s Success appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

What is Web3? Web3 In A Nutshell

Web3 describes a version of the internet where data will be interconnected in a decentralized way. Web3 is an umbrella that comprises various fields like semantic web, AR/VR, AI at scale, blockchain technologies, and decentralization. The core idea of Web3 moves along the lines of enabling decentralized ownership on the web.

Understanding Web3

To better understand Web3, it may be helpful to first describe a little internet history.

The evolution of the internet is often separated into three distinct stages: Web 1.0, Web 2.0, and Web 3.0.

Web 1.0 was the first iteration of the internet, with most users consuming content on websites that contained information in the form of text and images. These sites were served from a static file system and featured low levels of interactivity. Many call Web 1.0 the read-only web.

Web 2.0 is, for the most part, the internet in its current state. This iteration is social and interactive and there are more users creating content as opposed to simply consuming it. Web 2.0 gave rise to several sites that were more interactive and built upon user-generated content. Here, content is siloed, centralized, and run by corporations such as Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Airbnb. Web 2.0 is often referred to as the read-write web.

The Web 3.0 era is now beginning to emerge and is a key component in solving many of the problems associated with a centralized Web 2.0. Instead of the internet being controlled by a few organizations, Web 3.0 favors privacy, transparency, data ownership, and digital identity solutions. This functionality is underpinned by decentralized networks, blockchain technology, and a tokenized economy.

What are the core characteristics of Web3?Though the shift from Web 1.0 is Web 2.0 is relatively simple to define, the shift from Web 2.0 to Web 3.0 is less clear.

To provide clarity on Web 3.0, consider the following specific innovations and practices that define it:

Semantic web – Web 3.0 improves web technologies to generate, share, and connect content through search and analysis based on an ability to understand the meaning of words. This differs from Web 2.0, which relies on an understanding of keywords and numbers.Artificial intelligence – Web 3.0 is also able to decrypt natural language and understand intention in much the same way humans do. What’s more, it can recognize real information from fake information. This results in faster, relevant, reliable, and more intelligent results which meet user needs.3D Graphics – the third generation of the internet also integrates 3D and VR technologies to blur the line between the physical and digital world. Examples include museum guides, geospatial applications, computer games, and eCommerce product guides.Connectivity – information within Web 3.0 is more connected via semantic metadata, enabling the user experience to be enhanced by leveraging all available information.Ubiquity – in the Web 3.0 era, the internet is accessible to everyone, everywhere, all of the time. At some future point, internet connectivity will no longer be restricted to Web 2.0 devices such as computers and smartphones. Internet of Things (IoT) will facilitate the creation of novel types of connected devices.Web3, decentralization, and Blockchain[image error]A Blockchain Business Model according to the FourWeekMBA framework is made of four main components: Value Model (Core Philosophy, Core Values and Value Propositions for the key stakeholders), Blockchain Model (Protocol Rules, Network Shape and Applications Layer/Ecosystem), Distribution Model (the key channels amplifying the protocol and its communities), and the Economic Model (the dynamics/incentives through which protocol players make money). Those elements coming together can serve as the basis to build and analyze a solid Blockchain Business Model.The desire for decentralization started to grow after users on centralized networks began to fear for the privacy of their personal data. At more or less the same time, the popularity of Blockchain and cryptocurrency also began gathering momentum.

As a result, Blockchain in the Web 3.0 era incorporates the five characteristics mentioned in the previous section on a decentralized, peer-to-peer network. Using Blockchain technology and its immutable encrypted data, the need for centralized corporate operators is made redundant.

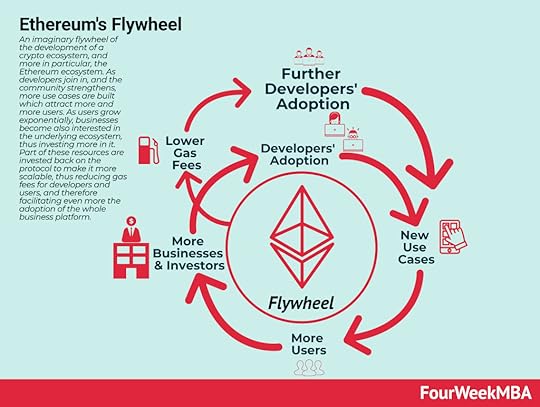

The Ethereum platform is currently the Blockchain platform most closely resembling the characteristics of Web 3.0.

An imaginary flywheel of the development of a crypto ecosystem, and more in particular, the Ethereum ecosystem. As developers join in, and the community strengthens, more use cases are built which attract more and more users. As users grow exponentially, businesses become also interested in the underlying ecosystem, thus investing more in it. Part of these resources are invested back on the protocol to make it more scalable, thus reducing gas fees for developers and users, and therefore facilitating even more the adoption of the whole business platform. Key takeaways:Web3 is a version of the internet where data will be interconnected in a decentralized way. It emerged in response to the limitations of a centralized Web 2.0, where a few large corporations control the internet. Web3 is perhaps best described by the specific innovations and practices that define it. These five characteristics include semantic web, artificial intelligence, 3D graphics, connectivity, and ubiquity.Web3 and Blockchain incorporate the five characteristics of a decentralized, peer-to-peer network with immutable and encrypted data. Ethereum is arguably the Blockchain platform embodying most aspects of Web3.

Blockchain Business Models Book

An imaginary flywheel of the development of a crypto ecosystem, and more in particular, the Ethereum ecosystem. As developers join in, and the community strengthens, more use cases are built which attract more and more users. As users grow exponentially, businesses become also interested in the underlying ecosystem, thus investing more in it. Part of these resources are invested back on the protocol to make it more scalable, thus reducing gas fees for developers and users, and therefore facilitating even more the adoption of the whole business platform. Key takeaways:Web3 is a version of the internet where data will be interconnected in a decentralized way. It emerged in response to the limitations of a centralized Web 2.0, where a few large corporations control the internet. Web3 is perhaps best described by the specific innovations and practices that define it. These five characteristics include semantic web, artificial intelligence, 3D graphics, connectivity, and ubiquity.Web3 and Blockchain incorporate the five characteristics of a decentralized, peer-to-peer network with immutable and encrypted data. Ethereum is arguably the Blockchain platform embodying most aspects of Web3.

Blockchain Business Models Book

Read Next: Dissecting Blockchain Business Models, Blockchain Flywheel: Inside Ethereum’s Distribution Flywheel.

Read Also: Proof-of-stake, Proof-of-work, Bitcoin, Dogecoin, Ethereum, Blockchain, BAT, Monero, Ripple, Litecoin, Stellar, Dogecoin, Bitcoin Cash, Filecoin.

Main Free Guides:

Business ModelsBusiness StrategyMarketing StrategyBusiness Model InnovationPlatform Business ModelsNetwork Effects In A NutshellDigital Business ModelsThe post What is Web3? Web3 In A Nutshell appeared first on FourWeekMBA.

Developing A Business Strategy With The Strategy Lever Framework

Developing a successful business strategy is about finding the proper niche, where to launch an initial version of your product to create a feedback loop and improve fast while making sure not to run out of money. And from there create options to scale to adjacent niches.

Business strategies make sense only in hindsightI have a business mantra that goes along these lines:

Business strategies take years to roll out. Yet when they do, they are obvious only in hindsight.

For the entrepreneurs who roll them out, that is all but a linear process. Rolling out these business strategies is a painful process, which requires a lot of faith in your own gut instinct, and it’s all about sweat, persistence, execution, and stubbornness.

And it all starts by balancing out the short and long term.

Balancing short term survival with long-term (at times) grandiose visionAs Jeff Bezos explained many times over, many decisions seemingly do not make sense in the short term. They do with a long-term perspective. Therefore, as an entrepreneur, it’s critical to balance short and long term.

From here let me give you some examples of how short term and long term are two different creatures, and yet they feed each other:

Profit is different from liquidity: when you run a business, that might seem obvious. But as you see it making the first profits, you might still struggle with profitability. As perhaps your clients’ payment cycles are long or your suppliers’ payment cycles are short. Or both. In other words, getting to profitability is great, but if you don’t have liquidity to invest back into the business, to create options to scale, not much useful for the long run.Being right in the long-term does not guarantee survival: while we all love to be right. If you don’t manage to survive the short-term, that won’t be much needed. Regrets will hunt you down, as you see others successfully executing on your same idea, but with more ability to balance the short term survival to the long-term vision, which leads to the next point. You might have a grandiose vision, but you need reality checks: we all like to think of ourselves as changing the world. For how noble this thought might seem, this also can easily lead to failure. When building up a business, execution takes up most of the effort. Thus, without built-in reality checks (is the product feasable? do people want it? is it adding value to the right people?), it’s easy to fall into the business cimitery.So how to minimize the risk of a bad execution? Let’s build some premises before we can lay down the whole framework.

Action plan: can you hold it in your head? If not, throw it awayBack in 2006, as Tesla was trying to pull off its first model, the Roadster, one thing was clear. The grandiose business plan who had been drafted a few years earlier by Tesla’s co-founders (Elon Musk would become CEO only in 2008) proved quite wrong.

That’s not because the people who drafted it were not smart. On the opposite, they were so smart to be able to put together a complex scenario analysis and have it drafted as a business plan. Yet when execution came, the costs and timing to produce the electric sport’s car were, by far, quite off. This also led to a final internal fight, where the initial co-founders (Martin Eberhard and Marc Tarpenning) were ousted.

In the meantime, in 2006, Musk had drafted a master plan that looked like the following:

Source: Elon Mush Tweet

Source: Elon Mush TweetThis action plan, which was written down but could have been held in mind represented the key steps, took Tesla over fifteen years to roll out! And I’m sure Elon Musk might have rehearsed it over and over, through the years.

The niche is the reality checkFrom a market launch perspective, how do you balance short and long term?

The answer is the niche. Or a subsegment of the market that will enable you to kick off a feedback loop to improve the business quickly. In fact, a “market” is too big to even understand whether your product is making a difference.

I know this might sound trivial. Yet, there is a critical reason why the market niche you pick is so important:

This serves as the center stage to present your product. It helps narrow down the scope of the business, thus make it much much simpler to execute. But most importantly, when you start something new, the most valuable thing to have – to progress fast – is to kick off a feedback loop. When you target too wide market, there is no feedback loop in place. Why? Because the environment you target is so complex, that to understand wheter you’re doing something right or wrong is impossible. That is why a much smaller market segment, is way more simple to tackle. A niche, the smaller it is, the easier to target, to track the progress of your business and trigger “learning feedback loops”.This last point is extremely important to stress. In fact, we can argue that the most valuable asset for our business over time, is a continued “learning feedback loop” where the market is able to tell us what we’re doing wrong, and how we can improve. In a niche market, the audience is small enough to give us this feedback. When the audience is too large and spared, it’s very hard to make any conclusion at all.

Complex systems are fractalsBenoit Mandelbrot who coined the term “fractal” made fractal geometry an incredible tool to describe the real world. A fractal is a sort of pattern that repeats itself at various scales. A great example of that is the cauliflower, a cruciferous vegetable with a very interesting shape. In fact, if you zoom in, you find the same pattern and shape repeated over and over.

I took this picture for you at the local supermarket. This, in particular, is a Roman cauliflower, and as you can see, if you zoom over and over again, you will find a self-repeating pattern. The same shape over and over at various scales. As a sort of Russian Matryoshka doll.

In short, complex systems in the real world are very very irregular. They do look similar at various scales (a neighborhood is made of blocks, a city is made of neighborhoods, a country is made of cities). Yet when things scale up and down, the dynamics change. This is what a complex system means. It’s not about the shape itself, but the size and scale which determine the dynamics of the system.

Why is this important to us, here? A few implications:

Smaller scale is easier to handle, as complex dynamics kick in exponentially at wider scale (you don’t control large, complex systems) Complex systems are mostly perturbated. Therefore, the more you take on a larger market the more you expose yourseful to unknown risks, volatility and therefore chances to fail. A bigger opportunity, but not a reversible one. It’s true there is a much bigger opportunity in a larger market, but there is a point in which you cannot reverse your position. As you get exposed to the largest chunk of the market, you can’t go back. Why? you have structured your whole company to survive in that market, and if that market suddenly changes, srhinks or it’s taken over by another market, the company might collapse.These are all things you need to be aware of when creating options to scale.

Create options to scaleAs you take over a niche, at that point you have options to scale. It’s worth highlighting that scaling to a certain extent can be a great way to grow your business. Yet, as you scale, once a critical mass is reached, everything will change. The wider the market, the less control you will have on it, and the more fragile your business might become.

From here it makes sense to adopt a transitional business model framework.

Transform the business at each stage (Transitional Business Modeling)As we’ll see later on, a transitional business model is a “temporary business model” that is executed to tackle various stages of growth. The premise that matters here is that as you move from a transition to the next, your whole business model changes, and this, in turn, might require a completely different business midnset.