James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 17

June 2, 2016

REVIEW: Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War by Karen Abbott

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War caught my attention because I like to read about topics that are somewhat off the beaten path. Karen Abbott writes about four women who served their country, whether it was the Union or Confederacy, as spies and in other functions.

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War caught my attention because I like to read about topics that are somewhat off the beaten path. Karen Abbott writes about four women who served their country, whether it was the Union or Confederacy, as spies and in other functions.

I had known some of what Belle Boyd did during the war, but the other women were new names to me. Honestly, Boyd had never impressed me. True, she was an effective spy, but it seemed like what she was doing was just as much about making herself important as it was to help the Confederacy.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow was a member of Washington society who was able to seduce politicians and military men into divulging secrets. I found her time in prison very interesting in how she refused to let it break her, but then she feared going back so it definitely had an effect on her.

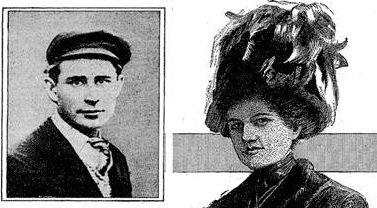

Belle Boyd

Elizabeth Van Lew was part of Richmond society who helped hide Union soldiers in her home and pass on information to the North. I actually found the story of Mary Bowser, one of Van Lew’s servants, more interesting. Bowser was hired in the Confederate White House and collected information right from Confederate President Jefferson Davis’s home and passed it on to Van Lew.

Emma Edmonds’ story was the one that truly caught my attention. She took on a male persona and became a soldier in the Union army where she fought, nursed soldiers, and served as a postmaster. She also went undercover as a female slave to collect information.

Emma Edmonds

The epilogue that explains what happened to these women after the war I found particularly interesting. Although I am pleased that the country recognized the contributions these ladies made to the war effort, not all of them led happy lives after the war.

Abbott does a great job of telling the stories in a compelling way, but sometimes the transitions between the stories was muddled. I found that I was quite fascinated to find out what would happen to these ladies.

I am surprised that Abbott included the stories of all four of these women in one book. I would think that any of them deserve their own book.

I was worried when I started reading that Abbott would write a feminist, politically correct book. I am pleased to say that is not the case. At times, I saw some things that might be construed that way, but that could have been because I was looking for it. By and large, it was a straightforward and compelling story.

Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy serves as a good introduction to these ladies, but you should look for additional books to flesh out the stories. Some reviewers have pointed out problems in some of the details that Abbott included. Many of these are minor problems, but some are distracting. One that caught my attention was her description of what the Confederate soldiers did to the Union dead after a battle. I have never read anything like that before and it seems so outrageous that she would have wanted to make sure that it was verified.

In other sections, I found myself thinking, “I wish I had written a passage like that in my books.” Abbott definitely made me appreciate the efforts of the women more than I had when started reading.

Author focuses on little-known nuns’ work during Civil War

Female reporter on Gettysburg Address gets her recognition 78 later

Radio interview about Civil War nursing

June 1, 2016

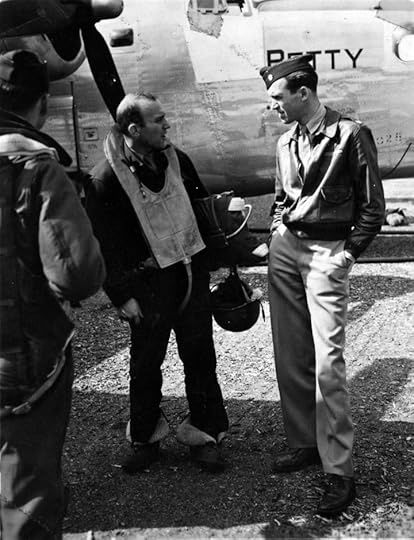

Hollywood at War, James Stewart, the first star to enlist, and he was the real deal, flying 20 combat missions — BEGUILING HOLLYWOOD

May 26, 2016

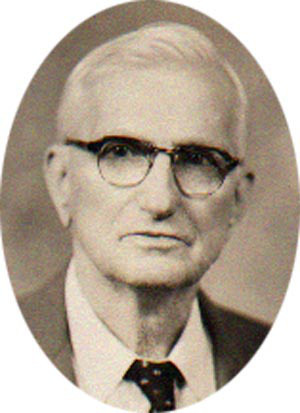

Getting paid what he was worth

A. Stover Fitz

When was the last time you heard of a public official not only volunteering, but insisting that his salary be more than cut in half? When have you ever heard of it?

It was as rare in the 1950’s as it is now. That’s why when Waynesboro, Pa.’s assistant manager and treasurer did it in 1958, it was reported in newspapers around the country. It probably also made a lot of public officials hope that the people they served didn’t expect the same thing from them.

“I feel you’re paying me too much, it’s not fair to me nor to the public,” A. Stover Fitz told the Waynesboro Council on Jan. 20, 1958, as reported in The (Chambersburg) Public Opinion.

It was a frank admission from a long-time borough employee. Fitz’s salary at the time was $4,000 a year, which is roughly $31,200 in today’s dollars. To further put it in context, the average income for a man in 1958 was $3,700 a year, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

So Fitz’s salary was only 8 percent above the national average, but to reach that amount, he was filling two roles for the borough and collecting both of the salaries for those positions. He collected the borough taxes in his role as borough treasurer and as the assistant borough manager, he provided assistance and advice to the borough manager.

“Make my salary $1,800 a year as treasurer and forget about the assistant borough manager title,” Fitz told the council.

He was willing to take a 55 percent pay cut and still perform the same duties. It wasn’t that he was being magnanimous; Fitz simply believed that public service should be more a service than a job. Fitz had worked for the borough in various capacities for 49 years. He had begun his career with Waynesboro as a part-time secretary in 1909. He rose through the ranks to eventually become borough manager before slowing down a bit to become the borough’s assistant manager and treasurer.

At 81 years old, Fitz wanted to enjoy his remaining years without having to feel the need to work all hours of the day to justify receiving two salaries.

“I want to feel free to work a half day when I feel like it, take a half day off for illness and to come in late when it’s snowing,” Fitz said.

Council President Harold J. Rowe praised Fitz for his integrity and said that the he believed that even when Fitz was working half a day, the work he did was still worth $4,000 a year. Fitz was insistent, though. He pushed his position and eventually convinced the borough council. The councilmen voted to cut Fitz’s salary “with reluctance.”

May 19, 2016

Bessie Darling’s murder haunts us still

Bessie Darling’s Thurmont home. Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

When the mail train from Baltimore stopped in Thurmont on Halloween, more than the mail was delivered. George F. Schultz, a 62-year-old employee with Maryland Health Department, left the train. Schultz hired Clarence Lidie and his taxi to give him a ride to the Valley View Hotel, which was 10 minutes away on the side of Catoctin Mountain.

As Schultz climbed into the car, Lidie noticed that he was carrying a .38-caliber revolver and remarked on it.

“Shultz laughed and remarked that ‘he didn’t know what he might run into’,” Edmund F. Wehrle wrote in a study about the history of Catoctin Mountain Park.

The Valley View Hotel was actually a summer boarding house, which had been run by Bessie Darling, a 48-year-old divorcee, since 1917. It was a large house built in 1907 that sat on a steep tract of land near Deerfield.

Darling, a Baltimore resident, had purchased the property from Mary E. Lent after Darling’s divorce in 1917.

“She generally managed the hotel in the summer and returned to Baltimore in winter, where she used her considerable social contacts to drum up summer business for her hotel,” Wehrle wrote. “Her skill at cooking and baking, as well as the scenic site helped build her a solid clientele.”

In the early 20th century, people took the Western Maryland Railroad from Baltimore to PenMar Park to enjoy the cooler mountain temperatures and to get away from the stresses of the city. Such was the appeal of the Catoctin Mountain area as a summer retreat that visitors always needed a place to stay.

“These such boarding houses offered the women of the area a rare opportunity to operate businesses,” Wehrle wrote.

Schultz had known Darling since 1926. They had become so close that Schultz had even spent Christmas 1930 with Darling’s family. Newspaper accounts at the time said they were romantically linked, and he often spent weekends at hotel while Darling was there.

Darling, who was 14 years younger than Schultz, met a lot people, both men and women in her work. In the summer of 1933, Schultz had become convinced that Darling was seeing Charles Wolfe, a 63-year-old man who had lost his wife a year earlier. He also lived in Foxville, much closer to the boarding house than Baltimore. (Wolfe later told the Hagerstown Daily Mail that he and Darling had been little more than acquaintances.)

The thought of Darling with another man made Schultz angry and he was known for his displays of temper.

“One Thurmont resident remembered that Schultz frequently drank, and, on one occasion, assaulted Darling during an argument in front of the Lantz post office,” Wehrle wrote.

While Darling forgave him that time, she was not so forgiving in this instance. Schultz and Darling got into a loud argument apparently over Wolfe, which ended when Darling left the hotel. She went to a neighbor’s home to spend the night and told the neighbor that Schultz was no longer welcome in her home, according to newspaper accounts.

Darling didn’t return to the hotel until Schultz left for Baltimore, and Darling didn’t return to Baltimore at the end of the tourist season. She decided that she would spend the winter in the hotel rather than having to deal with Schultz and his jealousy.

Around 7 a.m. on Halloween morning, Schultz came up to the rear entrance of the hotel as Maizie Williams, the 18-year-old maid, was coming out for firewood. Schultz demanded to see Darling. Williams said Darling was in her room and tried to close the door on the man.

Schultz forced his way inside. Williams hurried upstairs to Darling’s bedroom to warn Darling with Schultz following. Williams entered the bedroom and locked the door behind her.

This didn’t stop Schultz for long. He forced the lock and opened the door. Then he entered the bedroom and shot Darling who fell to floor dead.

Schultz then calmly told Williams to make him coffee. She did and when he finally let her leave the house to get help for Darling, he told her, “When you come back, you’ll find two of us dead.”

Williams rushed out of the hotel to the nearest home with a phone. She called Frederick County Sheriff Charles Crum who drove to the hotel with a deputy around 9:30 a.m.

They entered through the basement door because Schultz had locked all of the doors and windows. When they entered the Darling’s bedroom, they found her lying dead at the foot of the bed.

They also found Schultz nearly dead from a self-inflicted gunshot to his chest. Crum brought Dr. Morris Bireley up from Thurmont to treat Schultz, who was then taken to the hospital in Frederick.

Once Schultz recovered from the wound, he was tried for murder on March 13, 1934. The prosecution called 26 witnesses in their case of first-degree murder. Schultz claimed that Darling had also had a pistol and his killing her had been an act of self-defense. The jury deliberated an hour and found him guilty of second-degree murder and Schultz was sentenced to 18 years in the Maryland State Penitentiary in Baltimore.

Wehlre recounted the story of Charles Anders who had been in the courtroom when Schultz was sentenced and, 66 years later, still remembered watching Schultz sob as the verdict was read.

The drama of the murder fed into the tabloid style journalism of the day and people followed the case with interest.

“Even today, the murder stirs an unusual amount of residual interest,” Wehrle wrote.

May 12, 2016

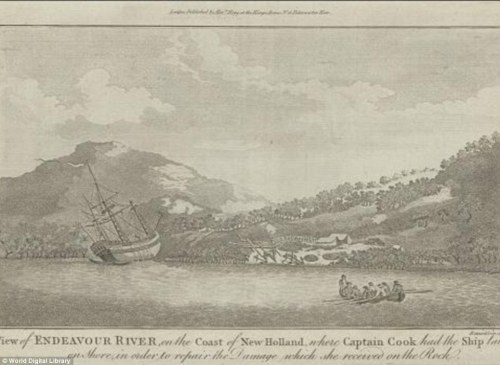

Capt. Cook’s ship located after 238 years

Captain Cook’s ship, Endeavour, has finally been located after 238 years. It was a ship that led an interesting history and now hopefully part of it can at least be salvaged and preserved.

Captain Cook’s ship, Endeavour, has finally been located after 238 years. It was a ship that led an interesting history and now hopefully part of it can at least be salvaged and preserved.

The Daily (UK) Mail reported on the find last week. The Rhode Island Marine Archaeology Project discovered the ship, which they say had been scuttled in Newport Harbor in 1778 by British forces in the lead up to the Battle of Rhode Island.

Orignally named the Earl of Pembroke, the ship was launched in 1764. The British Navy purchased the ship in 1768 and remnamed it the Endeavour. The ship and crew began exploring the Pacific Ocean and to search out a previously unknown, but suspected, continent, called Terra Australis Incognita.

It found Australia and made landfall on April 29, 1770. Captain Cook charted the coastline and then returned to England, arriving in 1771, nearly three years after the ship had set sail.

Cook’s efforts won him a promotion, but the Endeavour sat in dock largely unused. It was sold to a shipping magnate in 1775. However, once war broke out, ships were needed to join in the fight. “That individual then tried to sell the ship back to the British when the demand for ships increased during the war but they would not accept the vessel given its age and what it had been through over the years,” the Daily Mail reported.

The man made major repairs to the boat and renamed it Lord Sandwich. He then offered to sell it again and this time, the Navy did buy it.

It arrived at Rhode Island to serve as a prison ship for captured Colonial soldiers. It was blown up in 1778 to try and create a blockade of the harbor. The remains of the ship were found among thirteen others that were probably scuttled for the same reason.

While I hope something can be done to preserve the ship, I don’t hold out much hope. It’s a wooden ship that has been underwater for nearly 240 years. The will be fragile.

I remember when C&O Canal boats were uncovered during construction in Cumberland, Md., they had been buried for roughly 60 years. Engineers deemed them too fragile and costly to restore so they were simply reburied.

May 5, 2016

Labor trouble on the C&O Canal

The C&O Canal basin at Cumberland, Maryland.

Capt. John Zimmerman had his crew move the canal boat, Joseph Murray, under a chute for the Maryland Coal Company to take on a load of coal at the Cumberland Canal Basin on August 4, 1873.

He worked with his son and two hands to position the canal boat’s open hold under the church. It was something that occurred many times daily at the basin as canal boats prepared to haul coal to Georgetown and 1873 was the height of the canal’s “golden age.” By the end of the year, 91 canal boats would be built in Cumberland, bringing the number of boats navigating the canal up to 500, each with an average capacity of 112 tons.

The problem was that the Maryland Company hadn’t agreed to pay the uniform rate of freight that the canallers were insisting upon to offset increase hauling costs including a 5 cents per ton toll increase that had been raise in February. Though the canallers were unionized, they had agreed to not haul freight on their boats for companies that wouldn’t pay the uniform rate.

Zimmerman knew that he was breaking with his fellow canallers, but he had “boasted that he would let no man stop him,” according to the Cumberland Daily Times.

He had not tried to hide when he left the Maryland Company office and headed for the Joseph Murray. Nor had he been secretive when he moved the boat under the coal chutes.

The other canallers knew what he was doing and they didn’t like it.

“Hardly had the first pot of coal touched the bottom of the hold before the deck of the ‘Joseph Murray’ swarmed with boarders. Zimmerman made a show of resistance but was shoved off into the canal; his son and the other members of the crew leaving the vessel without further notice,” the Cumberland Daily Times reported.

The mob then chopped the stern post and destroyed windows on cabins. As they prepared to move onto other areas of the boat, someone realized that the canal boat belonged to Dave Eckelberry of Hancock and not Zimmerman. He was only employed by Eckelberry to captain the boat.

They stopped their destruction, but not their taunting of Zimmerman.

“While Zimmerman was struggling in the water, he was pelted with lumps of coal,” the newspaper reported.

He got out of the water and walked dripping wet to the office of the Maryland Coal Company. He took out his wallet and removed the money to dry and return it to the company agent in the office. Zimmerman had been paid extra to haul the coal for the company.

The other canallers swarmed into the office and swore at and threatened Alexander Ray, the company agent from Georgetown. “No blows were struck, however, and the demonstration ended in noise,” the newspaper reported.

Zimmerman left the office and headed into Cumberland. The crowd of canallers followed him and jeered him.

For Zimmerman, enough was enough. He “turned about, drew a revolver and threatened to shoot,” according to the newspaper.

Someone was able to knock the pistol from his hand while Joseph Kirtley ran off to issue a complaint against Zimmerman. A warrant was issued for Zimmerman’s arrest. He was taken before the magistrate, but eventually released on bail.

Captain Mills and other Cumberland police officers were sent to wharf to “quell any disturbance that might be in progress or that might arise, but on their arrival everything was quiet, and remained so throughout the day, although no other boat attempted to load for the Maryland Company,” the Cumberland Daily News reported.

The Maryland Company eventually shipped 110,663 tons of coal in 1873 or 14 percent of Cumberland’s business that year. It shipped the third-largest amount (out of 11 companies) in 1873.

For other posts about the C&O Canal:

The engineering marvel hidden underneath a mountain

The C&O Canal during the Civil War

C&O Canal murder mystery has surprising solution

April 28, 2016

Farm wife kept secret from Confederate occupiers

Mrs. Samuel Lightner appeared to be aiding the Confederate Army during the Civil War, but she was actually hiding bonds and securities from the Cumberland Valley Railroad from them.

Mrs. Samuel Lightner would never have considered herself an actress. She was a wife and a mother of eight and filling those roles was enough for anyone. However, in late June of 1863, she performed a role worthy of the best actresses of the time.

Despite the fact that her family supported the Union and her husband was in the army, Mrs. Lightner played the role of a Confederate sympathizer in order to save a railroad. Samuel Lightner had been drafted in 1862 as Chambersburg, Pa., worried about a Confederate invasion from Washington County.

For nearly a year, Mrs. Lightner had worked hard to keep the family farm near Greenville, Pa., running and to care for her eight children.

At the end of June 1863, a group of Confederate scouts rode up to the farmhouse asking to be fed. Mrs. Lightner had only a few minutes to make a decision. She “was fearful of displeasing the southern soldiers lest they retaliate by setting fire to the home,” according to the Public Opinion. Part of the fear certainly came from worrying about the safety of her children, but Mrs. Lightner also knew she was hiding a secret that she needed to protect.

Her decision made, she welcomed the soldiers and allowed them to camp on her farm. According to Benjamin Lightner, who was a youngster at the time, he mother spent the next week baking 25 loaves of bread for the soldiers and supplying each of the men with a pint of milk.

At the end of the month, the soldiers headed east where they would participate in the Battle of Gettysburg.

When word of what Mrs. Lightner had done leaked out, she experienced a lot of criticism among her neighbors. It wasn’t until years later that it became known that Emmanuel Hale, Mrs. Lightner’s father and a employee of the Cumberland Valley Railroad, had brought bonds owned by railroad to the farmhouse and asked his daughter to hide them. She had done so and this was another reason she had needed to keep the Confederate soldiers from searching the house or burning it down.

The Cumberland Valley Railroad was an early railroad that was chartered in 1831 and connected to Pennsylvania’s Main Line. It ran from Harrisburg to Chambersburg down to Hagerstown and Winchester, Virginia. In 1839, it became the first railroad to have passenger sleeping cars. The railroad had been used to supply Union troops during the war.

The Confederate army had already shown a willingness to destroy the railroad when soldiers tore down railway building in Chambersburg in 1862 around the same time Samuel Lightner was drafted. Around the same time as Mrs. Lightner was hiding the securities, the Confederate army had burned the railroad’s property in Chambersburg and torn up miles of track. A year after this incident, the Confederate army under Jubal Early returned to Chambersburg and burned even more of the railroad’s property.

One of the Lightner children, Mrs. W.F. Kohler of Scotland, Pa., told the story of the reason her mother had helped the Confederates to the Public Opinion in the early 1950’s.

April 21, 2016

Thank a World’s Fair for these everyday items

Mental Floss has a fun article about seven things that were introduced at World’s Fairs. It’s a good read, but it looks at only big items like the Eiffel Tower (introduced at the 1889 Paris World’s Fair) and the Ford Mustang (introduced at 1964 New York World’s Fair).

However, World’s Fairs have preview many new items that are more commonplace and still around today. Here are some of the ones that I could think of:

1893 Chicago World’s Fair

The pressed penny souvenir was first introduced at the 1893 World’s Fair. It had a very simply design compared to the ones seen today.

Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit Gum

Spray paint – Oddly enough, this was a display at the fair. It was developed by Francis David Millet as a way to finish some of the buildings on time for the fair to open.

Pressed penny souvenirs – They are standard at most tourist attractions nowadays.

Cracker Jacks

Pabst Blue Ribbon Beer – Originally called Pabst Select, the beer won a blue ribbon at the fair and the name change soon followed.

The Zipper

The telautograph – a very early version of the fax machine invented by Elisha Gray.

Cream of Wheat

1904 St. Louis World’s Fair

The Poulson Telegraphone was an early version of the telephone answering machine.

“An apple a day keeps the doctor away.” – This saying was created by J. T. Stinson a Missouri fruit grower who used it to promote apples.

The Poulson telegraphone – An early version of the telephone answering machine.

Tabletop stove

Coffeemaker

Electrical plug and wall outlet

1939 New York World’s Fair

I bet this dress made from cellophane, which was first introduced at the 1939 World’s Fair sounded worse that my old corduroy pants used to sound.

Cellophane – Among the uses DuPont pictured for this was clothing.

Nylon stockings

Television – The first U.S. television broadcast was President Franklin D. Roosevelt welcoming the visitors to the fair on opening day April 30, 1939.

1964 New York World’s Fair

1964 brought us Belgian Waffles, and I would guess, it was the same year the American waistline began to expand.

Belgian waffles

Picturephone – This was an early version of videoconferencing. Attendees could videochat in New York with people using a picturephone in Disneyland in California and other locations around the country.

I know a gentleman named Chuck Caldwell who attended the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair when he was 10 years old. He loved it. Although he didn’t get to attend, the fair featured the first Major League All-Star Baseball game.

The thing that he remembers most was the Sky Ride. Visitors rode elevators to the top of tall, steel towers that rose 628 feet into the air. One tower was on the mainland while the other tower stood 1,850 feet away across the lagoon on the fair’s island, which had been built atop a reclaimed landfill. From the observation deck there, he could see far into the city and over Lake Michigan. On clear days, a person could also see into adjacent states. An aerial track carried double-decker rocket cars across the lagoon and 210 feet above it for a distance of more than one-third of a mile to other tower.

He also had a hand in a circus display at the 1982 Knoxville World’s Fair. Howard Tibbals had been a fan of the circus since his childhood. In 1956, he began building what would become his lifetime passion, a scale circus. Such an undertaking required help and Tibbals had seen Chuck’s work as a sculptor and hired him to help built his highly-detailed model circus. Tibbals could build the miniature wagons and tents, but he needed Chuck to make the performers and animals for him.

Nowadays, unfortunately, the World’s Fairs aren’t even called that. If you’re lucky, they will be referred to as World Expositions, but often, they are called Registered expositions. They are also no longer an annual event. The last registered exposition was in Milan, Italy, in 2015. It ran from May 1 to October 31 of that year.

There are plans for a world exposition in Kazakhstan in 2017. So far, the United States is not one of the 30 confirmed countries that will be participating in it.

April 14, 2016

Trying to create a new county in Maryland

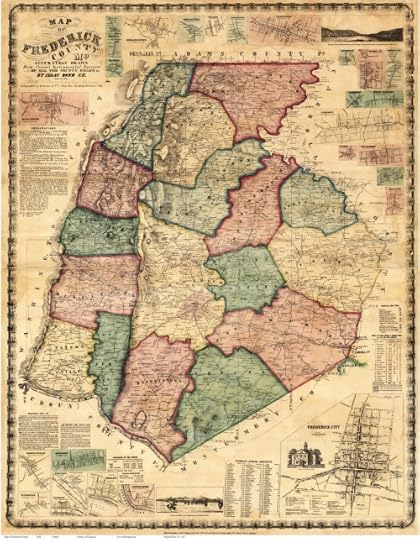

An 1858 map of Frederick County from the Library of Congress. During the 1870s, there was a movement in the northern part of the county to break away from Frederick County and join with parts of neighboring Carroll and Washington Counties to form Catoctin County.

Can you imagine a Catoctin County, Maryland? It would have included Frederick County north of Walkersville and Mechanicstown would have been the county seat.

It was a dream that some people in the northern Frederick County area pursued throughout 1871 and 1872. The Catoctin Clarion was only on its 10th issue when it carried a long front-page article signed with the pen name Phocion. Phocion was an Athenian politician, statesman, and strategos in Ancient Greece.

The issue had been talked about within groups of people for a while and it was time to garner support by taking the issue to a larger, general audience.

“Some sober sided citizens in our valley are quietly discussing the question among themselves, shall Frederick county be divided and the new county of Catoctin be erected into a separate organization?” the newspaper reported. Wicomico County had been formed in 1867 from portions of Somerset and Worcester counties so the idea of another new Maryland county was not far-fetched. In fact, Garrett County would be formed from the western portion of Allegany County in 1872.

The main reason put forth for creating a new county was the distance and expense of traveling to Frederick to register deeds and attend court. Opponents argued that creating a new county would be costly for the citizens in the new county. New county buildings would have to be constructed and county positions filled. All of this financial burden would have to be absorbed by the smaller population in the new county.

“Our neighbors across the Monocacy in the Taneytown District have but a short distance to go to attend Carroll county Court. Why shall we on this side be deprived privileges which were granted to them? Shall the people on one side of the Monocacy be granted immunities which are to be withheld from citizens residing on the other side?” the Clarion reported.

Besides northern Frederick County, Phocion said that in Carroll County, residents of Middleburg, Pipe Creek and Sam’s Creek were also interested in becoming part of Catoctin County.

“If a majority of the citizens residing in Frederick, Carroll and Washington counties (within the limits of the proposed new county), favor a division, I see no reason why it should not be accomplished,” the newspaper reported.

In deciding on what the boundaries of the new county would be, there were three conditions that needed to be met in Maryland. 1) The majority of citizens in the areas that would make up the new county would have to vote to create the county. 2) The population of white inhabitants in the proposed county could not be less than 10,000. 3) The population in the counties losing land could not be less than 10,000 white residents.

Interest reached the point where a public meeting was held on January 6, 1872, at the Mechanicstown Academy “for the purpose of taking the preliminary steps for the formation of a New County out of portions of Frederick, Carroll and Washington counties,” the Clarion reported.

Dr. William White was appointed the chairman of the committee with Joseph A. Gernand and Isaiah E. Hahn, vice presidents, and Capt. Martin Rouzer and Joseph W. Davidson, secretaries.

By January 1872, the Clarion was declaring, “We are as near united up this way on the New County Question as people generally are on any mooted project—New County, Railroad, iron and coal mines, or any other issue of public importance.”

Despite this interest in a new county, by February the idea had vanished inexplicably from the newspapers. It wasn’t until 10 years later that a few articles made allusions as to what had happened. An 1882 article noted, “It was to this town principally that all looked for the men who would do the hard fighting and stand the brunt of the battle, for to her would come the reward, the court house of the new county. The cause of the sudden cessation of all interest is too well known to require notices and only comment necessary is, that an interest in the general good was not, by far, to account for the death of the ‘New County’ movement. Frederick city, in her finesse in that matter, gave herself a record for shrewdness that few players ever achieve.”

A letter to the editor the following year said that the men leading the New County Movement had been “bought off, so to speak, by the promises of office, elective at the hand of one party, appointive at the hands of the other, and thus the very backbone taken out of the movement.” The letter also noted that the taxes in Frederick County were now higher than they had been when a new county had been talked about and that they wouldn’t have been any higher than that in the new county. “And advantages would have been nearer and communication more direct,” the letter writer noted.

April 7, 2016

A silent killer kills two people and two cats, but spares a rabbit (part 2)

Author’s Note: This is part two of the story I started last week. The columns ran in the Cumberland Times-News last year and recently won a local column award from the Maryland-Delaware-DC Press Association. Since I like the story, I thought I would share it with those of you who live outside of the Cumberland, Maryland, area. If you missed the first part, you can find it here.

Charles Twigg and Mary Grace Elosser mysteriously died on the eve of their wedding in 1910.

New Year’s Day 1911 should have been a day of rejoicing for the Twigg and Elosser families. Instead it turned into a day of mourning and mystery.

The day before, Charles Twigg and Mary Grace Elosser had been found dead in a room in the Elosser family home. Though the couple had been alone in the room, other family members had been in the house and no one heard anything suspicious and there were no marks on the bodies.

No one knew what had happened. Had it been a double suicide or a murder-suicide and why would either happen on the eve of their wedding?

An autopsy showed that both Twigg and Elosser had poison in their systems. Had someone poisoned them, making it a double murder?

Theories abounded. Twigg had originally been interested in Elosser’s younger sister, May, but had fallen in love with Elosser. Had May poisoned the couple out of jealousy? Had Twigg’s chewing gum been poisoned and he passed the poison to Elosser when they kissed? Anna Elosser, Elosser’s mother, was quick to accuse Twigg as a jealous murderer who had killed her daughter.

Eight-year-old Harlan Norris, a neighborhood boy, told investigators that he had seen the couple sitting with empty glasses and a bottle of green liquid between them. Anna Elosser said that the bottle had contained ammonia, which the family had used to try and revive Twigg and Elosser before they were known to be dead. The glasses had contained drinks that were also brought in to try and revive the couple.

Nationwide interest was quickly sparked over the mystery. Reporters from New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Pittsburgh, and other places arrived in Cumberland seeking answers and people to interview. The Elosser Family hired Pinkerton detectives to conduct an investigation independent of the Cumberland Police investigation.

Amid this controversy, the couple who should have been started the rest of their lives together were buried separately on Jan. 3. Elosser was buried in Rose Hill Cemetery in Cumberland and Twigg was buried at the Methodist church in Keyser.

At the coroner’s inquest, doctors Koon, Foard, Harrington, Broadrup, and Owens all testified that they had found cyanide in the blood of the Twigg and Elosser. Chemist George Baker concurred with their findings. What no one could explain was how it had gotten there.

The final conclusion of the inquest was that death had come from “poisoning administered in a manner unknown,” according to the Cumberland Evening Times.

Weeks after their death, the killer was identified as a small gas stove in the parlor. Drs. John Littlefield and A. H. Hawkins had been studying carbon monoxide poisoning and suspected that this is what happened to the couple. They replicated the situation in the Elosser home with a cat in a box sitting in for the couple. After 90 minutes in a closed room, the cat was dead. The experiment was repeated later in the day with a cat and a rabbit. This time, the cat died, but the rabbit survived.

The doctors who had testified of cyanide poisoning were skeptical at first. State’s Attorney David Robb continued following up every lead. Based on the new information, he had the stove in the Elosser home on First Street in South Cumberland examined.

The Cumberland Evening Times reported, “the startling discovery was made at the time of the test last week that the flue, in which the pipe from the gas stove fitted, was banked with soot, three feet high in the flue and seven inches thick at the base of the flue. There was absolutely no draft, and when the stove was lighted with the draft pipe in the flue, the flames boiled and emitted a gas odor.”

Because the couple had been closed in the room with no ventilation, they had been overcome by the poisonous fumes. Others who went into the room didn’t suffer the same fate because when they entered the room, the doors were open allowing for ventilation.

It was an accidental death and one of the earliest documented cases of carbon monoxide poisoning.