James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 21

August 27, 2015

Easter at Camp David

The Nixons leaving Easter services in Thurmont in 1971.

Anyone with eyes knew just where President Richard M. Nixon and his family were Easter Sunday morning in 1971.

It was pretty widely known through town that the Nixons would be spending the weekend at Camp David, a favorite retreat for the president. Since it was also Easter weekend, speculation was on whether they would attend church on Sunday and which church they would choose.

“Gold Cadillacs, television cameras, photographers, newsmen, and Secret Service agents do not stand outside of a church in Thurmont for the average person,” the Catoctin Enterprise reported.

The church was the Thurmont United Methodist Church where the Reverend Kenneth Hamrick was pastor.

Prior to the Easter service, Mrs. Hamrick had received a call from Camp David asking for her husband. Rev. Hamrick was officiating at another church, but when he returned home, his wife had him return the call. That is when he found out that he would have special guests during his service that day.

This visit apparently came about because of Mrs. Hamrick. “Rev. Hamrick, a part-time White House employe[e], attended a staff reception last Christmas at which time Mrs. Hamrick had asked Mrs. Nixon to bring the President to her husband’s church sometime in the future,” The Frederick Post reported.

Not only did the president and first lady attend, but they were joined by Julie and David Eisenhower, former First Lady Mamie Eisenhower, and Tricia Nixon and her fiancée Edward Finch Cox.

“I didn’t mention their presence to others attending the services,” Hamrick told The Frederick Post. “I did mention the President, as well as other world leaders, in my prayers at the end of the service.”

Rev. Hamrick’s sermon dealt with the rejection of both Christ and Christianity in biblical and modern times.

Afterwards, Hamrick told the Catoctin Enterprise, “The President said the sermon was ‘very good, very pertinent’ and it appeared that I ‘had done my homework’.” He added that the first lady told him, “It made my Easter Day.”

The Nixons and their guests then returned to Camp David for an Easter dinner. Two months later, Tricia Nixon and Edward Cox would return to Camp David to spend their honeymoon there after their June 12 wedding.

President Nixon enjoyed spending time at Camp David. It was a place where he could think, relax, and get work done. He had worked on his first acceptance speech as the Republican presidential nominee there as vice-president. Although John F. Kennedy won that election, Nixon would return to Camp David in 1968 as president.

Dale Nelson tells a story in The President Is at Camp David that Nixon speechwriter William Safire tried making a case to Nixon’s appointment secretary, Dwight Chapin, that the president should spend more time in the White House not on an isolated mountain.

“Do you want to be the one who tells the president he can’t go to Camp David? Because it sure as hell isn’t going to be me.”

According to Nelson, when former President Dwight D. Eisenhower died in 1969, Nixon wrote his eulogy at Camp David. He made the decision to order troops into Cambodia during the Vietnam War there. He wrote his 1972 presidential nomination acceptance speech there.

The Nixons also spent Easter 1972 at Camp David. They also celebrated David Eisenhower’s 24th birthday during that Easter weekend.

August 20, 2015

Small-town high school students prepare for the journey of a lifetime in the middle of the Great Depression (Part 4)

The boys of Arendtsville Vocational High School stopped at Lake Erie on their return trip to Alaska in 1937.

The boys of Arendtsville Vocational High School had already seen so much during the summer of 1937. They had traveled across the United States, down to the bottom of the Grand Canyon, and upon an ocean to reach Alaska. It was almost too much to take in fully, and yet, their journey wasn’t complete.

From Vancouver, British Columbia, they climbed aboard a half-ton truck that they had specially outfitted to carry the 25 boys and their teacher, Edwin Rice.

“Most of the roads in British Columbia are dirt and not very good at that,” Rice wrote in a letter to The Gettysburg Times. “We were saturated with dust when we got to Asveyoos.”

They drove into Washington State where they watched the construction of the Grand Coulee Dam.

“Today it is one of the largest dams in the world, but then it was only about 50 feet high under construction,” Wayne Criswell said in the unpublished article, “The Journey of a Lifetime Summer 1937” about Criswell’s memories as told to James Wego.

The boys also stopped in Yellowstone National Park where they tried to take a swim in the hot springs. Criswell noted in the article, “a mistake, really hot!”

Whereas, their trip to the West Coast had followed a southern route across the country, their journey home took them along a northern route. They passed through the Dakotas, Minnesota, Wisconsin and Michigan. They crossed into Canada to travel to Niagara Falls and traveled south into the United States and over to Erie, Pennsylvania.

They returned home on August 3, having been gone for a little over six weeks.

“It was a fantastic trip, but it was good to see little, but beautiful Arendtsville,” Criswell wrote. “I had enough of travel for awhile.”

They had visited two countries and 24 states and territories as they traveled more than 9,000 miles. It truly was the adventure of a lifetime.

Criswell also recognized that it wouldn’t have happened it not for Rice, a teacher who went beyond the call. “Arendtsville High School and our group of students were lucky to have a teacher like Professor Rice,” Criswell said. “One who was interested and dedicated to broadening the experience and interests of so many young people. We all recognized, no doubt much later, just how much effort and hard work that he had expended to give us the very special experience and how much it had contributed to our knowledge and awareness of the world around us.”

August 13, 2015

Small-town high school students prepare for the journey of a lifetime in the middle of the Great Depression (Part 3)

Students from Arendtsville High School aboard the Prince Rupert on their way to Alaska. Courtesy of Gary Weikert.

Few of the boys of Arendtsville Vocational High School had traveled beyond the borders of Adams County, but in a short time during the summer of 1937, they had visited two countries, traveled through 19 states and territories, swam in two oceans, and were getting ready to sail on an ocean.

They boys had traveled a southern route across the country with their teacher, Edwin Rice, but now they were in Vancouver, British Columbia. There, they boarded the steamship, Prince Rupert. Since the group was traveling on a shoestring budget, they had booked passage on the freight deck. It was cramped quarters. The boys slept in bunk beds and the rooms had no windows, “but we could see out when the doors opened,” Wayne Criswell said in “The Journey of a Lifetime Summer 1937” an unpublished article Criswell told to James Wego.

The ship sailed up the inside passage headed toward Alaska. At times the sea was rough and some of the boys realized that they were prone to seasickness. Rice wrote in a letter to The Gettysburg Times, “’Bud’ McDonald says he does not wish me any bad luck but he wishes that I would get sick so he and the others could laugh.”

By and large, the boys enjoyed the voyage. “The ship had a real theater where we saw a live program of singing and readings. Fancy stuff!” Criswell wrote.

The first stop on the voyage was at Ocean Falls where they toured the Pacific Paper Mills and saw how paper was made from the trees being cut down until the finished produce came out of the machines.

In Alaska, the Prince Rupert docked among Navy destroyers at Ketchikon. “The immigration officer made us prove that we weren’t foreigners trying to sneak into a United States Territory,” Criswell wrote. Alaska wouldn’t become state until 1959.

The Prince Rupert’s next stop was in Juneau. This town amazed Criswell who noted that a portion of the town was built over water on wooden pilings because there wasn’t enough room at the base of the mountains.

He delighted in how long the days were in Alaska. “It was funny to be awake late in the night (like 11:00 P.M.) and have enough daylight for reading the paper,” Criswell said. It was only dark for three or four hours a day.

The third Alaskan stop was in Skagway where all of the streets were dirt roads and the sidewalks were boardwalks. Being agriculture students, the boys took note of the fruits and vegetables displayed in shop windows, which were “two or three times the size of those we grow at home.”

Sighting a nearby glacier truly let the boys know that they were in a foreign land, despite the fact that it was part of the United States. “The steamer blew its loud and sharp whistle, making part of the glacier break off and fall into the sea,” Criswell said.

Another new sight was the influence of the Eskimos that could be seen around Skagway in totem poles, carvings, and brightly colored outfits.

The boys also took a short ride out to where gold was shipped from the Alaskan mines and miners purchased new supplies.

“The gold rush must have been exciting,” Criswell mused.

While there, they decided to stretch their legs and take a hike. Skagway is surrounded by mountains and they were told that a beautiful lake could be found midway up.

“We walked up to this lake and it was pretty nice,” Rice wrote. “Back of the lake was a high water fall with a lake high up above, we wondered what it looked like from the other lake.”

They started up the mountain again. Five of the boys tired too quickly and turned back. The rest made it to the second lake after about 90 minutes of climbing. They were now above the tree line and there was snow on the ground.

“Looking to the north we could see the sea with the little town below,” Rice wrote. “The shore line is covered with trees and above the trees are snow-capped mountains stretching away to the north and east.” He added that it was the second-most-beautiful sight that he saw on the trip.

As the boys sailed back to the Vancouver, they boys visited the Frazer River Valley and watched the Indians there dry salmon on racks in preparation for the winter.

They took some time to fish and Rice even caught his first fish. “The fish seemed very willing to be caught. Almost as fast as a line was thrown in, a fish was on it,” Rice wrote.

The group once more boarded the truck they had specially equipped for the journey and set off once again across the United States, this time taking a northern route.

August 6, 2015

Small-town high school students prepare for the journey of a lifetime in the middle of the Great Depression (Part 2)

Students from Arendtsville Vocational High School had to dig their truck out of mud during their trip to Alaska in 1937.

Twenty-six students from Arendtsville Vocational High School set out on a cross-country journey to Alaska and back on June 18, 1937. The trip had been years in the making and for the boys, many of whom had barely ventured to the furthest reaches of Adams County, no matter what happened, it would be well worth the wait.

They first headed east in their Ford half-ton flatbed truck, which had been specially outfitted to carry all of the boys, their teacher Edwin Rice, and everything they would need for their journey. Rice had taken his students on a number of summer trips over the years, but the 9,000-mile trip planned for 1937 was by far, the grandest trip that he had undertaken.

The traveled along the Eastern Shore of Maryland, Delaware, and down into Virginia. They stopped at Virginia Beach where the boys went swimming in the Atlantic Ocean. Many of the boys had never seen an ocean before, let alone swim in one.

Each evening the group stopped somewhere near a freshwater source so they had water to drink and wash with. They prepared their supper on the hand-made stove that they carried on the truck and performed different duties that they had been assigned. They camped out overnight and in the morning, cooked their breakfasts. Then they hit the road again stopping somewhere along the way for lunch.

Their southern route them through North Carolina, Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas.

“The vastness of the country was mind-boggling and the experiences came so fast that they are hard to recount,” Wayne Criswell, a former student at the high school, told James Wego in the unpublished article, “The Journey of a Lifetime”. “In Oklahoma we were in a terrible dust storm. This was the period of the famous Dust Bowl climate in the west and mid-west – crop failures that devastated countless farmers and their families.”

In Texas, they traveled along the famous Route 66, which at the time was little more than a dirt road, according to Criswell. For the most part, that was not much of a problem, but the group ran into heavy rains in New Mexico. They pulled a tarp over the open bed of the truck to keep the boys dry, but the dirt road turned into “gumbo road” that mired the truck. It forced the boys to get out and push the truck free.

In Arizona, the group visited the Grand Canyon and stood at the edge in awe of what they saw before them.

“There were nothing but cliffs, gorges, the river, and it went on forever,” Criswell said.

The boys hiked nearly eight miles along a narrow trail that wound along the sides of cliffs down to the Colorado River. Their joy at reaching the bottom of the canyon was interrupted when one of the boys had an appendicitis attack and had to be taken back up the canyon and driven 90 miles to the nearest hospital in Flagstaff, Arizona.

From Arizona, they visited Bryce Canyon in Utah and then traveled to Salt Lake City where the State Director of Education met them and introduced them to Governor Henry H. Blood, who spent about 10 minutes talking with the boys.

They also attended a concert at the Mormon Tabernacle, which apparently put some of the boys to sleep.

They had more fun floating in the Great Salt Lake and driving across the salt flats. The salt in the flats reminded the boys of snow.

“One of the boys suggested, I think it was John Lynn, that if his imagination were a little stronger he would have frozen to death. It would have taken some imagination for the thermometer stood around 105 degrees,” Rice wrote in a letter to The Gettysburg Times.

From Utah, they drove into the Nevada and the American desert.

“We had practically all the types of weather the desert has to offer,” Rice wrote. “In the morning, it was so cold that it was uncomfortable; by noon it was so hot it was worse than uncomfortable; by 4 o’clock in the afternoon, thunder stormed could be seen in the horizon and a cloud that looked like the worst kind of hail storm was directly in front of us.”

Out of the desert, they traveled up into the mountains and over Tioga Pass, which is nearly 10,000 feet above sea level.

“The road was so steep that we had to get out and walk next to the truck; otherwise it would not make it and overheat the motor,” Criswell said.

At the top of the mountain, the boys took a break and had a “terrific snow ball fight.”

Once in California, they headed down the mountain to Yosemite National Park.

“There were steep narrow roads with hairpin turns,” Criswell said. “It would take make times of backing up, turning, backing up, turning, etc. to finally find a straight road.”

They spent the night in Yosemite and got to see a “waterfall of fire.” In a practice that ended in 1968, a huge bonfire was set afire and then pushed over a high cliff.

From the park, they headed toward San Francisco, anxious to travel across the Golden Gate Bridge, which had opened to traffic just three weeks earlier.

“On our way to California we saw a truck carrying fresh apricots,” Criswell said. “Our truck was so close to it that we were able to “pick some off’. Maybe that is why they tasted so good.”

When they reached San Francisco, they were disappointed to find that they would not be allowed to drive their truck across the bridge. They had to take use the older Oakland Bridge instead.

They drove up the coast from San Francisco, passing through Oregon and Washington and into Canada. They stopped in Vancouver where they would leave the truck for a while to travel aboard the Prince Rupert of the Canadian National Steamship Line.

During this first part of their journey, the group from Arendtsville had driven through 19 states and territories, but now they were about to experience sailing on an ocean.

July 30, 2015

Small-town high school students prepare for the journey of a lifetime in the middle of the Great Depression (Part 1)

The students of Arendtsville High School preparing to set out across country in 1937 in their specially outfitted half-ton truck.

Arendtsville is a small town in south central Pennsylvania 3,800 miles from Alaska. In 1937, a group of teenagers set out from their little community with Alaska as their destination.

The teenagers were students of Arendtsville Vocational High School. The school had first opened as a two-year high school in 1911 on the second floor of the elementary school. Enrollment quickly grew and within a couple years the students moved to the second floor of the fire house on South High Street, according to the National Apple Museum web site.

The students got their own building in 1914 when the school board voted to build a high school on South High Street. The course work was expanded to a three-year program.

This was due to the urging of Edwin Rice, who was a student a State College. His arguments convinced people and support grew for a vocational school. In 1917, Butler and Franklin Townships joined together to establish the Arendtsville Joint Vocational High School.

Rice eventually became a teacher at the new school and every few years, he organized a summer trip for students. “Some teachers, it seemed, taught the subject matter in a very formal way; you either understood the material and passed or, for whatever reason, failed. Mr. Rice went far beyond the subject matter and was truly interested in broadening the horizon of education to the real world,” Wayne Criswell, a former student at the high school, told James Wego in the unpublished article, “The Journey of a Lifetime”.

During the summer of 1937, he planned to take 26 students on “a 9,000 mile journey in six weeks on the road to places only known from textbooks, stories by adults, or perhaps a rare movie,” Criswell said.

Rice had been taking his students on summer trips roughly every other year for the previous 15 years. So the idea of a summer trip was familiar with people in the community, but many, including staff at the high school, thought taking a 9,000-mile trip to Alaska and around the county was too much.

Rice didn’t think so. He’d been thinking about it for years. He knew that financing a trip was going to be hardest part. Each student would need to raise around $1,500, a princely sum during the heart of the Great Depression. Most families couldn’t afford to contribute much. Rice met with the families a few times to explain his plans and how each family could afford the trip.

However, the students were agriculture students so Rice arranged to lease about 30 acres of farmland.

“Every boy had to work on the fields, as part of his share of the expense. The harvested crop, done by the boys, was sold to a canning plant in Gettysburg (Burgoon and Yingling) and, of course, had to be transported to the facility,” Criswell said. The students going on the trip did this for three years prior to the trip.

Students also sold shell seeds during the winter.

By the summer of 1936, enough money had been raised that Rice purchased a half-ton truck with an open bed. It was a new 1936 Ford truck, but it was a demonstrator model. The truck was outfitted to hold all 26 boys and Rice. The open bed had benches installed along the sides and up the middle where the boys would ride. Each bench had a flip-top so that items could be stored inside. There was a clothing rack over the cab and a tarp was stored there that could be unrolled over the bed if it rained. Between the wheels on the driver’s side of the truck a handmade stove and cooking utensils. On the other side of the truck between the wheels, food and a keg of water were stored.

In addition to the money that needed to be raised, each boy had to take $50 dollars in order to purchase one meal a day. Each family also to supply 16 quarts of canned foods, which would be used to feed the boys at other times.

Each boy was assigned a duty that he was expected to do during the trip. For instance, Criswell’s job was to check the oil and water in the truck daily and top them off if needed.

Once the truck was outfitted and the parents’ questions answered, the group was ready to set off as the summer of 1937 began.

The students participating in the trip were: Paul Tate, Lester Carey, Donald Warren, Robert Knox, Roland Orner, Russell Barber, Blair Fiscel, Sterling Funt, Paul Cole, William Oyler, Wayne Criswell, Edgar McDonnell, Glenn Bream, Bruce Hartman, Joseph Redding, Warren Bushey, Orville McBeth, Jesse Fiscel, Rodney Taylor, John Andrews, Fred McDannell, Ralph Cooley, John Linn, Glenn Kime and Samuel Rice (the youngest member of the group at age 11).

July 16, 2015

REVIEW: The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime That Scandalized a City & Sparked the Tabloid Wars by Paul Collins

I bought The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime That Scandalized a City & Sparked the Tabloid Wars awhile back. It finally worked its way to the top of my “to read” pile. I wish I had read it sooner because I really liked it.

I bought The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime That Scandalized a City & Sparked the Tabloid Wars awhile back. It finally worked its way to the top of my “to read” pile. I wish I had read it sooner because I really liked it.

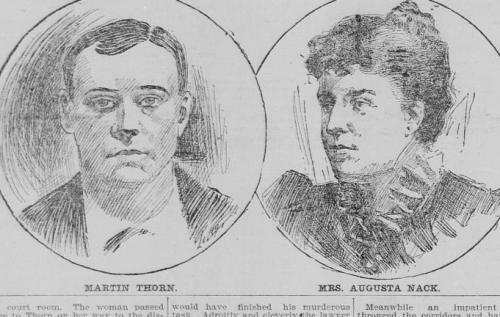

The main story involves the identification of a dismembered corpse. Once the body is identified as William Guldensuppe, which leads to two suspects, Augusta Knack, Guldensuppe’s lover, and Martin Thorn, Knack’s lover. However, it is much harder for the police to figure out which of the two suspects committed the murder and whether the other was a willing participant or a dupe.

While the pursuit of the murderer makes an interesting story in itself, the secondary story of how the newspapers played up the story to the point of actually becoming part of the story is just as interesting. Reporters planted evidence, interrogated witnesses, and enlisted their readers in the search for missing body parts.

This was the age of “yellow journalism” with the newspapers of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer competing against each other to be number one.

The story flowed like a bestselling mystery and kept me interested throughout. I kept bouncing back and forth over which of the two suspects committed the murder.

Collins also does a great job of setting the scene. He puts you in the period with colorful descriptions of life in the city.

I found after reading the book that I was searching the Internet looking for the newspapers and books mentioned in the book.

July 9, 2015

Rejected four times, Menchey becomes a decorated veteran

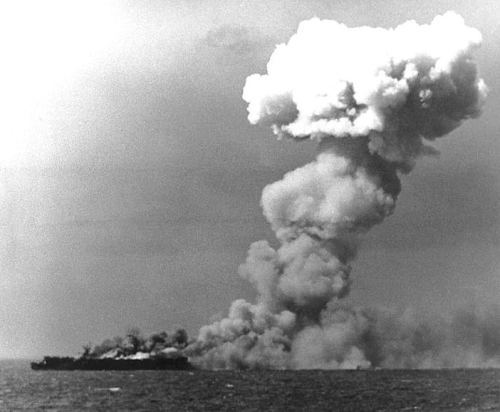

The U.S.S. Princeton burning after she was hit by a Japanese bomb during the Battle of Leyte in WWII.

Before Francis J. Menchey could fight for his country amid the islands of the Pacific Ocean during World War II, he first had the win the battles against the draft boards at home that didn’t want him to fight.

When Menchey graduated from Gettysburg High School in 1943, the U.S. had been at war with the Axis Powers for about 18 months. Like many Americans, the young man wanted to do his part to help his country. Shortly before his graduation, he traveled to Baltimore to try and enlist in the U.S. Navy.

The U.S. Navy rejected him because the physician at the enlistment center said Menchey had a hernia. That was news to Menchey who felt perfectly fine and had never had any indication that he had a hernia.

“Returning to Gettysburg, Menchey consulted his family physician who declared that he was physically fit for service,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

He tried to enlist locally and was told the same thing. He was unfit because he had a hernia. Then the local draft board called for him to enlist, but he was again rejected for a third time as being unfit.

After graduation, Menchey took a job with Eastman Kodak in Rochester, N.Y., but he didn’t give up on his hope of serving in the military. He had the plant’s physician examine him.

“There just isn’t anything wrong with you,” the doctor told him.

So Menchey tried to enlist in Buffalo, N.Y., and was turned down for a fourth time.

When he returned to Gettysburg for Christmas with his family in 1943, he was called up for induction by his draft board again. He traveled to Harrisburg where he was examined and finally, on this fifth attempt to join the military, he was accepted. However, he was told that he would be leaving on January 4, 1944, for army boot camp. Menchey wanted to join the navy. He asked to be reassigned to the navy but he was turned down.

“He then appealed to a Navy Commander who ‘changed’ the induction paper after he confirmed Menchey’s statements that his Navy enlistment papers of several months previous were still on file,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

Menchey reported to boot camp at Great Lakes and was then sent to corpsmen’s school in San Diego and onto Radium Plaque Adaptomter’s school on Treasure Island off San Francisco.

“Six months after his induction Menchey was at Pearl Harbor and a few weeks later he was aboard a task force flagship en route to his first engagement at Angar in the Peleliu group,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

He also participated in the battles of Leyte, Luzon and Iwo Jima. One time a Japanese bomber strafed Menchey’s ship, wounding 17 men and barely missed crashing into the ship.

The Battle of Leyte was a two-month-long battle against the Japanese in the Philippines. It was the first battle in which the U.S. forces faced Japanese kamikaze pilots. Menchey’s ship was the acting general communications ship for the attack force. It was under an air attack 85 times in 30 days and general quarters was sounded 149 times during that month. Menchey was part of a medical group of six doctors and 27 corpsmen who took care of the wounded and dying who were brought aboard the ship. At one point, they were caring for 215 men with serious injuries and 375 ambulatory wounded. When the fighting was finished, nearly 53,000 soldiers had been killed.

Menchey was given a month-long leave in early 1945 and returned home to visit his family.

“Rejected three time by the navy and turned down once by draft board examiners Francis J. ‘Dick’ Menchey, Pharmacist Mate Third Class, is home from the Pacific wars with four battle stars and an extra star for having survived 85 air attacks in thirty days while his ship was laying off Leyte Island, 13 of his 18 months were spent in the Pacific war zone,” the Gettysburg Times noted.

He was discharged from the Navy in in February 1946. When he returned home, he brought his new wife, Della C. de Baca, whom he had met in San Francisco.

This local hero died in 2002.

July 2, 2015

Ignoring facts doesn’t make them false just forgotten

I am reluctant to write about this topic because the subject of the Confederate flag along with some other recent events have generated more anger and rudeness online than I have ever seen. I’ve watched friends turn on each other and rather than try to speak rationally about a topic, they simply “unfriend” each other on Facebook.

I am reluctant to write about this topic because the subject of the Confederate flag along with some other recent events have generated more anger and rudeness online than I have ever seen. I’ve watched friends turn on each other and rather than try to speak rationally about a topic, they simply “unfriend” each other on Facebook.

However, other things have happened this week or occurred to me that, I think, had shown me some different angles on the topic that I felt compelled to share because I haven’t seen some of them mentioned.

First off, I’ve seen written in newspaper reports that the Confederate battle flag in South Carolina was flying above the state house. First, this is not true. Second, this is being reported by the media, which seeks to have to public trust them, but can’t get the story right. The Confederate flag is flying above a Confederate memorial on the grounds of the state house. It did fly for years above the state house, placed there by a Democrat administration. A Republican administration moved it to the Confederate memorial. Yet, the Republicans are the ones being accused of being racially insensitive by the Democrats for supposedly doing what the Democrats actually did.

Politics aside, the controversy over the flag has now led to people calling for the removal of Confederate memorials, names, and statues from everything. I have seen more vitriol about this issue than there was among the actual veterans who fought and died under the flags during the Civil War.

In 1913, more than 57,000 Civil War veterans came together in Gettysburg. It was the largest reunion of actual veterans ever held and included both Union and Confederate veterans. Just before the event happened, a rumor spread that no flags of the Confederacy would be allowed. Confederate veterans started to talk about boycotting the event. The organizers heard what was happening and issued a statement that essentially said that all flags from the war would be allowed, but the United States flag would be the largest and fly the highest.

Just about everyone was fine with this. Confederate General E. J. Hunter said, “This is a united country, and has only one flag. The fact that the one flag is the flag carried by our war enemies 50 years ago means nothing any more. We left our sacred emblems home.”

Pictures from the reunion show both flags flying with the United States flag predominant, as it should be.

During the week-long event, former enemies walked together, laughed together, and shared memories. They did not yell at each other and call each other names. They did not belittle each other because one side was the victor and the other wasn’t.

They engaged in civil discourse.

Today, it has gotten to the point that groups want to replace the American flag and remove the Jefferson Memorial because Jefferson was a slaveholder. The memorial isn’t there to help people remember that Jefferson was a slaveholder. It’s there because he was the third President of the United States, the man who doubled the size of America, and the author of the Declaration of Independence.

Where I live in Gettysburg, the sponsors of a living history event have said that they aren’t going to allow the Confederate flag to fly at the event. So are they uninviting Confederate re-enactors? Are they only going to tell one side of the story of the Civil War?

These are certainly attempts to rewrite history. I’ve heard “rewriting history” applied to a different interpretation of facts. I may not like the interpretation, but as long as facts are used, I don’t have a problem with it. It’s when the facts are altered, misrepresented, and omitted that I have a problem.

The current efforts against the Confederate flag remind me of when an iconic photo of President Franklin D. Roosevelt was altered to remove the cigarette holder from his mouth years ago. What it showed was a lie because the group didn’t want to deal with the fact that Roosevelt smoked.

I was working on a newspaper column this week and went to research a subject at the local historical society. In doing so, I found a letter written by a college history professor to the author of an article that ripped apart an article the author had written.

He wrote, in part, “Until the law requires training and license to practice history, we can expect to find almost anything in speech and print which from those whose method is best described as without fear and without research.”

While I don’t disagree with the latter part of his statement, I do disagree with the former. First, it would be a violation of free speech and I was stunned that a professor would actually advocate that. Second, it promoted the government as the gatekeeper for what is correct. That would lead to government-approved speech, and you can see where that will get you with all of the politically correct speech out there.

There are lots of historical stories out there and lots of viewpoints. Let them all be told. Let them even be challenged. Then teach our children to think with their heads and not their hearts so that they can evaluate what they read.

Instead what I see is that the politically incorrect views are being ignored or even written out of history books. There’s no chance of civil debate or one side swaying the other. The topic is simply presented as “settled.” If that was true, the country wouldn’t be ripping itself apart right now.

The old saying goes, “Those who don’t know their history are doomed to repeat it.”

Leaving out a full representation of both sides of debate is how it starts.

To see how it ends, look at what happened to other cultures that forgot their roots. That is, if you can find it in a history book.

June 25, 2015

Frederick County’s (Md.) last slave, part 3

Ruth Bowie had grown up as a slave during the Civil War. Even after gaining her freedom, she had remained with a former owners until she married Charles Bowie in 1880.

By the turn of the of century, the Bowies were listed as living in log home along Lewistown Pike in Lewistown, which is where they would call home for their rest of their lives. They had had four children together, but none of them lived to adulthood and then Ruth had to deal with the loss of her husband in 1920.

The Frederick News was reporting that Ruth was over 100 in 1946. The newspaper ran a short article noting that Ruth’s doctor had decided that she was too old to continue living alone. Her sight and hearing were still considered normal, but she had hurt her hip shortly after she had turned 100 a year earlier. He doctor wasn’t sure that she could continue caring for herself.

“The first hundred years aren’t the hardest. It’s after the first hundred years that things begin to get tough,” she told the newspaper.

The Frederick Emergency Hospital, which is now the Montevue Assisted Living Center, became Ruth’s new home. She became a fixture there sitting in her low broad-armed chair and relating her quickly fading memories to her friends who would come to visit her.

“For a woman who has had only one day’s schooling in her life, she is remarkably discriminating in her choice of words. There was almost a wink in her smile when she related that she had not gone back to school after her teacher had whipped her on the first day because she was so ‘full of devilishness,’” Mehl wrote.

When her friends visited, they would often bring her treats of chicken, sugar cakes and peppermint candies, which were Ruth’s favorite foods.

“I like peppermint candy best,” Ruth told the Sun Magazine.

According to Diane Grove, administrator at Montevue Assisted Living Center, Ruth was discharged from the emergency hospital on May 22, 1955, at the age of 107.

When Ruth died later that year on November 23, she was the oldest resident of Frederick County. She had also been readmitted to Montevue because of her deteriorating health. The Rev. Charles Corbett officiated at her funeral when she was buried at Creagerstown Lutheran Church Cemetery.

“Every life is important and every story has its place in history but it’s what you do with that life that’s important,” said Dwight Palmer, president of the Frederick County NAACP.

Though Bowie was not a civil rights icon, she represented the goals of the civil rights movement. She had risen from slavery to make a life for herself. She was well loved in the community by people of all colors. Despite the fact that she had no family to care for her, friends had visited Ruth frequently during her time at Montevue. Also, at a time when segregation still existed, Ruth’s pallbearers were all white men who considered themselves her friends.

June 21, 2015

Frederick County’s (Md.) last slave, part 2

The Mullinix Farm where Ruth Bowie lived as a slave during the Civil War.

Ruth Bowie was born a slave in Montgomery County, Maryland. When she died in 1955, she was the last person in Frederick County, Maryland, who had been born into slavery.

Slave Life

Letha Brown was a house servant and cook for the Mullinixes while Wesley was a field hand.

“Well she remembers the days of her slavery when custom permitted owners to wield the whip ‘for the least little thing’ and little Ruthie often felt the sting of the switch,” Sullivan wrote.

However, Ruth’s experience with this came from her interactions with Asbury’s wife, Elizabeth Mullinix whom she called “Ol’ Missy.”

Hilton says he has no doubt that Ol’ Missy beat Ruth. “She treated everybody like that not just Ruth,” Hilton said. “Family stories say she was a crazy woman.”

For the most part, Ruth worked in the main house. She was brought up to be a house servant like her mother. She would wash and iron clothes, clean house and take care of the Mullinix children.

“Often she would sit on a three-legged stool, crooning to the baby while her mistress in long hooped skirts worked a spinning wheel across the room,” Mehl wrote.

During Ruth’s childhood, the Mullinix farm switched from growing tobacco to general farming. This meant that fewer slaves were needed to handle the workload.

“Tobacco had blighted the land and general farming wasn’t as labor intensive as tobacco farming,” Hilton said.

So Mullinix reduced the number of slaves he owned. The ones he freed and who chose to remain on the farm help with the raising of corn, wheat and cattle.

The Civil War

As the country split in two during the War Between the States, Ruth had memories of soldiers riding along the country roads in Montgomery County. Some of them would camp near the Mullinix farm, steal horses or just generally frighten people.

Nearly 100 years after the fact, Ruth still remembered the day soldiers broke into the main house looking for food. She heard them coming and hid behind a sugar barrel.

One of the soldiers found her and yelled, “I’m hungry!”

“They’s meat in the pot an’ bread in the box,” Ruth whispered in fright.

The soldiers took the meat and bread and left without causing any more problems except that the family went hungry that night.

Though Ruth could remember the incident past her 100th birthday, whether the soldiers had been Union or Confederate escaped her.

Another day that Ruth never forgot was April 14, 1865, the day Abraham Lincoln was assassinated.

What’s less certain is whether she attended the Gettysburg Address two years prior.

“Now she doesn’t know, but young friends say years ago she used to talk about that great day in Pennsylvania and they’re prone to believe that she was there,” Sullivan wrote.

Ruth stayed with the Mullinixes until she married Charles Bowie in 1880. He had fought in the war on the Union side. After the war ended, he had returned to Frederick County to work for Dr. T. E. R. Miller until he fell off a wagon, injuring his right arm so badly that it had to be amputated.