James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 20

November 5, 2015

Looking Back 1949: The boy who was missing part of his heart

Dr. Alfred Blalock performs one of his early heart operations at Johns Hopkins University. Courtesy of Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives, Johns Hopkins University.

James “Jim Boy” McKenzie of Lonaconing had lived nearly four years with only three-quarters of his heart, but time was running out for the young boy.

When Jim Boy was born in 1946, it was without the right ventricle of his heart. The right ventricle is one of the four chambers of the heart. It pumps deoxygenated blood from the heart through the lungs and back to the left atrium in the heart.

Without the ventricle, Jim Boy was able to live but he suffered from a unique version of the Blue Baby Syndrome. Blue babies have poorly oxygenated blood that is blue in color rather than red and this blue blood causes their bodies to look blue. In Jim Boy’s case, it was only his hands, feet and lips that apparently turned blue.

His parents had taken Jim Boy to Johns Hopkins Hospital four times over his short life and “specialists informed them they could do nothing for Jim Boy at the time, but possibly could aid him if he lived a little longer,” the Sunday Cumberland Times reported in December 1949.

So Jim Boy returned home with no relief in sight and his condition grew worse. He suffered an attack in August 1949 and was admitted to Allegany Hospital. For six weeks, Dr. Thomas Robinson watched over Jim Boy trying to find an effective treatment. Nothing worked.

Jim Boy was admitted to Johns Hopkins on Oct. 27 for the fifth, and what many people expected to be the last, time.

Doctors told the McKenzie family that things didn’t look good for the youngster. He had two blood clots in the main artery leading to his heart and two more were forming in the main artery to Jim Boy’s brain.

Doctors Alfred Blalock and Helen Taussig took on the case and recommended surgery for Jim Boy, but they only placed his chances of survival at 60 percent. According to the Sunday Cumberland Times, “later the specialists gave him even lesser odds as he never ate much, weighed only 24 pounds, could hardly walk two feet without falling and his breath was very short.”

Blalock was the surgeon-in-chief of Johns Hopkins Hospital and professor and director of the department of surgery of the medical school. He had become well known when he showed that shock generally came from the loss of blood. He recommended using plasma or whole-blood transfusions as treatment for shock, treatment that is credited with saving the lives of many casualties during World War II. He had also developed the use of shunts to bypass obstructions in the aorta.

Taussig’s interest in cardiology and congenital heart disease led her to discover that the major problem with Blue Baby Syndrome was the lack of blood reaching the lungs to be oxygenated.

In 1943, she overheard a conversation Blalock was having with another doctor about his shunt technique when she began thinking it might have an application in treating Blue Baby Syndrome. She interrupted the conversation and began brainstorming ideas with Blalock.

From this conversation, Blalock and Taussig developed a successful way to treat Blue Baby Syndrome. The first operation using shunts to treat Blue Baby Syndrome took place in November 1944 and was successful. The following year, the pair published a joint paper on the first three operations in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

By the time Jim Boy came to them, Blalock and Taussig were famous for successfully treating Blue Baby Syndrome. If anyone could help Jim Boy, they could.

The surgery lasted four hours, during which they transferred the main artery of Jim Boy’s right arm to his heart and a near-normal function returned to the boy’s circulatory system, according to the Sunday Cumberland Times.

A half an hour after the operation, Jim Boy was conscious enough to recognize his mother and his lips were already turning pink.

By post-operative day two, he was more talkative and on day three the nurses were calling him “Chatterbox.” He was released from the recovery room to a regular room on day four.

In the following month, Jim Boy gained two pounds, his chest expanded and he grew 1.25 inches.

His parents said, “The two doctors who have restored the warmth to our son’s hands and feet certainly have put a warm spot for them in our hearts.”

October 29, 2015

The champion coal miner of the world

When Lawrence B. Finzel trudged home from the Western Maryland coal mines each day, he knew he had done a good day’s work. In fact, he knew he’d done a good two or three days work.

When Lawrence B. Finzel trudged home from the Western Maryland coal mines each day, he knew he had done a good day’s work. In fact, he knew he’d done a good two or three days work.

In 1917, Finzel was called the champion coal miner of the world “who just before the recent wage increase became effective earned $347.92 in one month mining coal,” according to The (Oakland) Republican.

He accomplished this by mining an average of 12 tons of coal daily at a time when a good day’s work at the region’s mine was five tons of coal.

“He leaves his home with his fellow miners and returns with them and does as much work as two or three ordinary miners with apparent ease,” the Cumberland Evening Times.

Though he accomplished this great feat in Hooversville, Pa., Finzel was born in Garrett County and had worked in mines in Maryland and West Virginia, accomplishing similar feats.

He came from a mining family. His father, Henry, was a German immigrant who settled in Garrett County and mined for half a century. Finzel was one of six brothers who were taught to be industrious not only in the coal mines but on the family farm.

“When the farm was in good state of cultivation and the work could be done by the boys in the evening, the boys went into the mines. After digging coal the greater part of the day, they came home and worked on the farm,” The Republican reported.

His industriousness paid off for him. Coal mining pays miners by the amount of coal they mine. When Finzel worked for the Consolidation Coal Company, he was “drawing the largest pay for any miner in the small-vein mines in that region,” according to The Republican.

He took a job in West Virginia working for the Saxman Coal and Coke Company near Richwood. “Working in a seam of coal three feet high, he earned $2,360 in one year, and average of $196 per month. He loaded 4,000 tons of coal, an average of 12 tons daily. This is believed to be the greatest amount of coal ever dug by one miner in the State of Virginia,” The Republican reported.

He then moved his family to Hooversville to work for the Custer & Sanner Coal Company. He was told that the previous earnings record for a miner was $175 in two weeks. Finzel set to work to break the record. During the first two weeks of October 1917, he earned $136.97 (with a poor car supply) and during the back end of the month, he earned $211.05, which broke the previous record handily. Finzel even thought he could have done $400 during the month if he had had a good car supply in the early part of the month.

It was such an accomplishment that it made news around the country, particularly in newspapers in coal-mining regions.

He also held a record for mining 600 tons of coal in a month, according to the Cumberland Evening Times.

“On one occasion he was given a heading to drive and two other miners were given an air course. In one month Finzel had driven the heading sixty feet deeper in the coal than the others had driven the air course,” the Connersville, Ind., Daily Examiner reported.

For all his great accomplishments in the mine, Finzel was not a large man. He was described as being of medium height and his friends called him “the little big digger.” Because of his great feats, he was often examined by doctors looking for something that made him special. The Cumberland Evening Times noted that “a physical examination at John Hopkins Hospital he was pronounced the finest muscled man that ever came to the institution.”

Finzel died two years later after his record-setting month, on January 19, 1919, from complications from pneumonia. He left behind a wife, a daughter, and three sons.

According to the Charleston (W. Va.) Gazette, Finzel’s headstone read: “He led the world in coal mining during the World war.”

October 22, 2015

FREE historical fiction novels

For a limited time, I am offering three of my historical novels for free. If you’ve been reading my blog and enjoying the posts, here’s your chance to grab three free novels. By clicking on this link and signing up, you’ll be able to download Canawlers, The Rain Man, and October Mourning.

For a limited time, I am offering three of my historical novels for free. If you’ve been reading my blog and enjoying the posts, here’s your chance to grab three free novels. By clicking on this link and signing up, you’ll be able to download Canawlers, The Rain Man, and October Mourning.

Canawlers is my favorite among the historical fiction novels that I’ve written. It follows the Fitzgerald Family as they try to keep their canal boat running along the 185-mile-long C&O Canal during the Civil War.

Midwest Book Review wrote, “A powerful, thoughtful and fascinating historical novel, Canawlersdocuments author James Rada, Jr. as a writer of considerable and deftly expressed storytelling talent.”

I wrote this book after biking the C&O Canal with my wife. Up until that point, I had little interest in history, but I fell in love with the canal and wanted to tell a story set on it.

The Rain Man is set during the 1936 St. Patrick’s Day Flood on the Potomac River. It was a devastating flood. If you ever get a chance to go to historic Harpers Ferry, there’s a building there with all the flood high-water marks on it. The one for 1936 is the highest mark on the building and well above the first floor. A flood like that seemed like a great setting for a novel.

This Rain Man is a mystery thriller set during the day of the flood as a Cumberland City police officer pursues a killer through a city that is quickly being submerged.

In the fall of 1918, Spanish Flu killed around 60 million people worldwide in two months. That was about 2 percent of the world’s population. People were terrified and with good reason. It is the deadliest disease known to man and no one knew how to stop it.

Now imagine that someone was deliberately aiding in the spread of the flu? That’s the idea behind October Mourning.

Reviewer’s Bookwatch said, “This is a very good, and very easy to read, novel about a famous, yet unknown, bit of 20th Century American history.”

There’s no trick involved here. I’m working on building my mailing list, and as a way to say “Thanks for signing up,” I’m offering these e-books for free. Their normal retail price would be $16. Enjoy them, and let me know what you think.

https://aimpublishing.leadpages.co/fb-hf-box-set-test/

October 15, 2015

Gentleman of the Old School (Part 2)

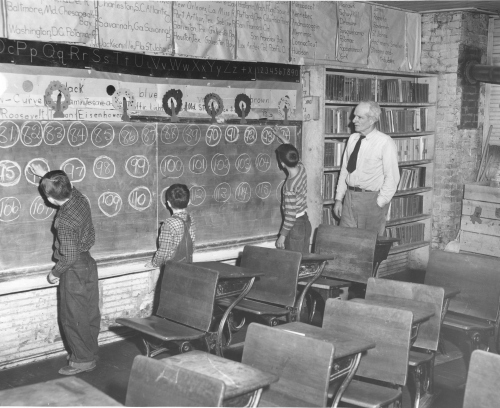

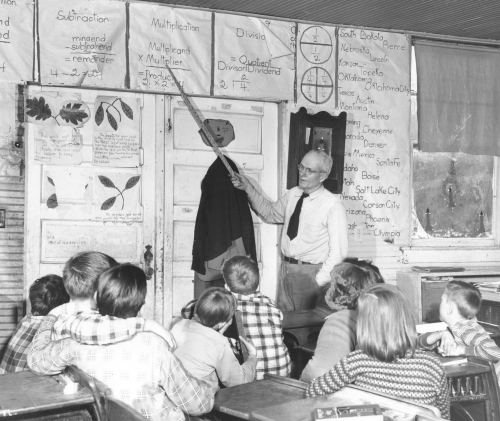

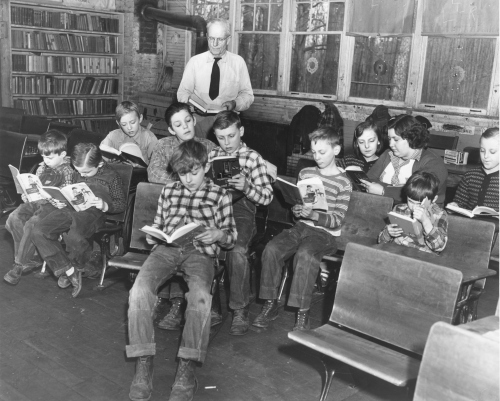

William McGill teaching at Phillips Delight School, the last one-room school in Frederick County, Maryland. Courtesy of ThurmontImages.com.

During his last years of teaching at Philip’s Delight, William McGill’s day began at 7 a.m. when he would get in the station wagon and drive up Catoctin Mountain on roads “so winding an narrow that he blows his horn constantly to warn the lumber wagons which frequently come the other way,” William Stump wrote in an article for the Sun Magazine. The change in elevation was 1,500 feet over six miles of road.

He would stop at the farms and cabins and pick up the older school children and then take them back down the mountain to Thurmont High School. Many of them were his former students so he would catch up with their lives and their studies during the trip.

Once he dropped them off, he would turn around and head back up the mountain. If he passed the homes of any of his current students, he would stop to pick them up. When they arrived at Philip’s Delight School, it would already be warm because two students who lived closest to the school had the job each morning to fetch wood from the shed and get the fire started in the iron stove that served as the building’s heating system.

“It was still cold at times because it wasn’t insulated,” said former student Austin Hurley of Thurmont.

Another former student, Betty Willard of Thurmont remembered that on those cold days the students were allowed to move their desks so that they were closer to the stove. Also, because the school did not have electricity when she attended, foggy days would make it hard to see inside the school since the windows were only on one side of the building. On those days, the students were allowed to move their desks closer to the windows in order to be able to read their books.

Like many other buildings on the mountain, Philip’s Delight School had no indoor plumbing. The students had to use the two outhouses behind the school.

“You just had to watch out for snakes, bees and spiders when you opened the door,” Betty Willard said.

Inside the school, the wooden floor of the school was black from the oil it was polished with to keep down the dust. Seven rows of desks filled the room and bookshelves, coat racks and blackboards were mounted on the walls. The walls were in need of a fresh coat of paint, but it was hard to tell this because posters covered just about all of the free space on the walls.

The posters were part of McGill’s teaching style. He told The News, “If a fifth grader has forgotten something basic from the previous year all he has to do is look around. In fact, there’s hardly a spot to rest a day-dreaming eye without absorbing knowledge.”

Most of the student arrived by 8:30 a.m. The girls would often bring flowers to put in bottles to brighten the room. The boys would get buckets and walk down a lumber trail to the Willard Farm a quarter mile away. They would fill the buckets with water and then walk back to the school. The water they brought would be the school’s water supply for the day.

The students each brought their own tin cup to school. If they got thirsty during the day, they would use a dipper to get water from a bucket and fill their cup.

The school had electricity, but only after January 1952. Up until that time, a student would ring a school bell to note the beginning of classes. After that time, an electric buzzer was used.

The school day started each morning with the students reciting The Lord’s Prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance.

Then McGill would begin teaching his lessons to seven different grades of students with the skill of a master juggler. Stump described one scene this way:

“Seating the first-graders with picture books, he sends third, fourth and fifth graders to the blackboards with instructions to write the names of the characters in their books. Looking at his watch, he reads aloud with the seventh.

“McGill is not still for a second. Neither is he excited—although every second is one of enthusiasm for him,” Stump wrote.

At lunch time, many students walked home for lunch, but others ate at the school. Though some of the schools in Frederick got a hot lunch program earlier, hot lunches didn’t come to many of the county’s rural schools until 1923 and even then, calling it a “hot lunch” was generous.

“At Philip’s Delight hot cocoa is served at noon each day and the milk for this beverage is carried by the teacher for a distance of about six miles to the school. There are about 30 children enrolled in the school,” The News reported.

Some other rural schools would have hot soup instead of cocoa. The purpose wasn’t for the cocoa or soup to be lunch but to supplement the lunch the students brought from home.

Before the students could eat their lunches, they would say grace. Then McGill would sit with them and talk while they ate.

After lunch, the student would play outside while McGill sat on the porch watching over them. Once recess had ended, there would be another session of afternoon classes until the day ended and McGill became a bus driver again.

Betty Willard remembered that McGill would also take the students on field trips. She remembered one such trip when McGill had all of the students bring a sack to take a field trip to gather mushrooms. However, as they walked through the woods to the mushrooms, McGill would have students identify trees and wildflowers that he pointed out.

McGill said of his teaching philosophy in The News, “I’m strong on fundamentals; you won’t believe it, but I talked to a high-school student not long ago who said the capital of the United States was Annapolis. That why I stress places and locations so much; I’ve always done it and I always will.

“Yet it’s more than that. I teach the fundamentals of religion—because there are no churches up here,” McGill said in the Sun Magazine.

He put the school’s location to his benefit in teaching, taking the students on walks in the woods to view animals or using acorns for counting. His goal was to keep them busy and to have fun and rarely did he have discipline problems.

“And in a school like this, every last pupil gets close attention from the teacher—and the young ones benefit from being in the same room with the older ones,” he told The News.

Betty Willard enjoyed working with the younger students when she finished with her own lessons.

“I think that is where I got the desire to teach,” Willard said. She taught school for 40 years, including teaching at the last two-room school in the county, which was in Foxville.

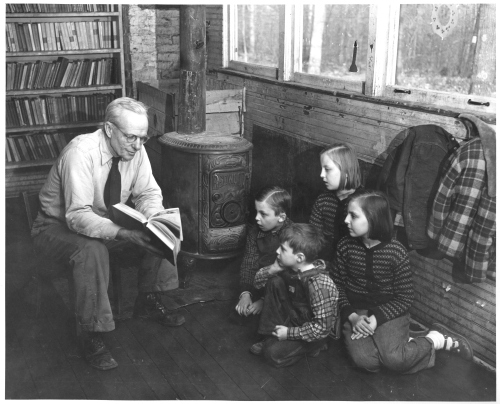

William McGill teaching at Phillips Delight School, the last one-room school in Frederick County, Maryland. Courtesy of ThurmontImages.com.

Closing the school

When McGill was transferred to Catoctin Furnace School in the middle of the 1954-1955 school year, no other teacher could be found to take his place at Philip’s Delight and so the decision was made to close the school. With only 13 students in the school, Superintendent Eugene Pruitt decided that two-thirds of the costs to operate the school could be saved by bussing the students to Catoctin Furnace School, and as an added benefit, McGill would still be teaching them.

McGill retired from teaching in 1958 at the mandatory age of 70.

“I’ve tried to give an education and make it pleasant for the pupils. I know I’ve had a good time,” McGill told the Frederick Post.

When this teacher of the county’s smallest schools died at age 85 in 1973, it made the front page in The News.

According to former student, Gideon Willard of Thurmont, the school building sat deserted until 1961. After a snowstorm, the old roof was overburdened with snow and collapsed and the school had to be torn down.

Though Philip’s Delight was one of the last one-room schools in Maryland, the last one-room school to close down was in Tylerton, a small island community in the Chesapeake Bay. When it closed in 1994, it had only nine students with five of them moving on to middle school the next year.

William McGill teaching at Phillips Delight School, the last one-room school in Frederick County, Maryland. Courtesy of ThurmontImages.com.

October 8, 2015

Gentleman of the Old School (Part 1)

Phillip’s Delight School was the last one-room schoolhouse in Frederick County, Md. Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

William McGill would have laughed at the idea that students need to be educated in $60-million-plus schools to get a good education. He would have known. For nearly a quarter century, he taught school in the last one-room school in Frederick County.

“Some people are of the opinion that youngsters can’t get an education in a one-room school. That isn’t keeping with the facts,” McGill told the Sun Magazine in 1952. “Since 1910, I’ve been teaching in schools like this, and I wish I had a dollar for every one of my pupils who went to the university. Why, last year Betty Ann Willard, a girl I taught, was the honor graduate at Thurmont High.”

Philip’s Delight

Philip’s Delight School was located off an old lumber trail surrounded by thick woods high up on Catoctin Mountain. Before the school closed on February 1, 1955, the families on the mountain had had their own school since 1800.

Albert Hauver, a 96-year-old resident on the mountain, told McGill the history of the school in 1943. The families living on the mountain in 1800 sought a location to build a school for their children.

It is said that Philip Fox found a locations and declared, “What a delightful spot for a building,” according to McGill. People started calling the spot Philip’s Delight and built a log cabin on the site that served as the school until 1886. That year, the building burned down. Another building was built a short distance away that served as the new school until 1932 when it also burned down. The final school building was brought into the area from Foxville and served until the school was closed. William Stump, writing for the Sun Magazine, said that the final building was “a dull, weather-beaten building, and the years have made it swaybacked, like and old plowhorse.”

Despite its exterior, the school was relatively well equipped. McGill told The Frederick News in 1943, “Many visitors drop in on us during the school year and they frequently manifest surprise at our modern equipment, such as cards, charts, wall maps, textbooks, test materials and library books. The superintendent and supervisors have made it their policy to furnish all school children in the county with as near equal opportunities as possible.”

During its 155 years, Philip’s Delight was always a one-room school with never more than few dozen students in grades one through seven. When the school finally closed, it only had 13 students.

Teacher William McGill teaching students in the Phillip’s Delight one-room school. Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

William McGill

McGill was the last teacher at the school and it was because of his strong support of the school that it remained open as long as it did.

When the school burned down in 1932, McGill told The News, “The superintendent’s office said, ‘Ah! Now we can bring those pupils down the hill to Thurmont.’ So they announced that they were not going to rebuild, and they put on a new school bus. And you know what happened?

“It ran for four months, and it didn’t have a single passenger!”

The families who lived on the mountain didn’t want their children traveling on the narrow, winding road up and down the mountain twice a day. In the winter, the roads could quickly turn icy, which made them even more dangerous.

McGill volunteered to teach at the school, but after a few years was transferred to act as the principal at Foxville School. However, by 1946, the Philip’s Delight School had gone through a number of teachers; none of whom wanted to teach in such a small school and isolated area. The Frederick County Board of Education began discussing closing the school, which parents again resisted vehemently.

McGill gave up his principalship and moved once again to Philip’s Delight School where he taught until 1955.

McGill was the son of an Episcopal minister who was born near Catoctin Furnace. He attended Old St. Paul’s School in Baltimore and Thurmont High, but he did not attend college initially. Once he was a teacher, he did study summers at Johns Hopkins and Western Maryland College.

He began teaching in Frederick County’s small rural schools in 1910. He would teach as many as 84 students at a time, some of them 21 years old.

“Got arrested twice for fighting with my pupils, then. They were as old as 21 in those days, and didn’t have a whole lot of respect until I drilled it into them,” McGill told The News.

Despite his early fights, McGill became a teacher who was loved and respected by his students and parents.

“He was the last of the one-room school teachers in the county, and in his early days he taught in areas where there were no communications and some of the patrons could not read or write. In some cases, Mr. McGill was the main liaison with the outside world for medical services, letter writing, and the like,” The News reported.

In his later years, he was often called “Gentleman of the Old School.”

During the 1940’s McGill would bike from Catoctin Furnace seven miles up hill along narrow roads to reach the school. If it was snowing, he would walk the distance. By the 1950’s, McGill had added school bus driver (actually, it was a station wagon with “school bus” painted on the rear) to his duties, but this allowed him to be able to drive to school.

October 1, 2015

Thurmont’s alligator population

Handlers at the Catoctin Zoo tape an alligator’s jaws shut to prepare it for transport to its winter residence.

Nowadays seeing exotic animals in Thurmont is no big surprise. The Catoctin Wildlife Preserve and Zoo has around 400 wild animals on display across 50 acres.

However, 139 years ago, Thurmont’s animal population was lots of cows, pigs, dogs, cats, chickens…and one alligator.

Andrew Sefton was one of Thurmont’s leading citizens in the 19th Century. He arrived in Thurmont, which was then known as Mechanicstown, in 1831. The town at that time had a population of around 300 people, according to Sefton. Not only was there no Catoctin Zoo, the town had no churches (though the United Brethren in Christ Church was under construction) and no street lights.

Sefton wrote, “the streets were lit up a night from the doors and windows of the merchants’ shops, which made them very brilliant.”

He listed the town and nearby vicinity as having seven tanners, two blacksmith shops, a tilt hammer, grand stone, polishing wheel and turning lathe, all propelled by water power, one wool and cloth factory, two shoemaker shops three tailors, three weavers, one gunsmith, one silversmith, two wagon and coach shops, two mill-wrights, three cabinet maker and house carpenter shops, one saddler, one hatter, one doctor, three stone and brick masons, three hotels and a match factory.

After living in town for about 18 months, Sefton was able to purchase a piece of property on East Main Street. Sefton quickly set to fixing up the property.

Around that time, he also married Elizabeth Weller, the daughter of Jacob Weller, B.S., on March 18, 1833.

“We at once occupied our newly repaired and windows home and have been living in the same house ever since. We have had seven children born to us in this house, five sons and two daughters, all of whom are living, and at this time they are living in four different States of the Union,” Sefton wrote in the Catoctin Clarion.

In 1876, one of the Seftons’ sons, Joseph, was traveling in Florida. On his journey, Joseph thought he had found the perfect gift for his father. He bought it, had it boxed up and shipped to his father.

It arrived here in mid-October. Sefton opened up the box and found that his son had sent him an alligator. It was a young one that was about two feet long and was “greatly admired by the many—male and female—who have gone to see it,” according to an article in the Catoctin Clarion in 1876.

American alligators are found in the southeast United States. Louisiana has the largest alligator population. They live in freshwater as ponds, marshes, wetlands, rivers, lakes, and swamps. As reptiles, they need warm temperatures to regulate their bodies and an environment that doesn’t freeze over.

“Mr. S. is very anxious to keep it alive, but those who understand the nature of these animals say it will be impossible to do so, as the climate and water of this State are not adapted to the culture of alligators,” the Clarion reported.

While Sefton’s alligator was only two-feet long, large adult alligators can grow to around 13 feet and weigh 800 pounds. They can also live to be more than 70 years old.

“Should it live and grow to be a big one, no doubt there will be a scarcity of babies and small boys in this neck of the woods some day, as it is said they have a peculiar faculty for clawing up children and [African Americans],” the Catoctin Clarion reported tongue-in-cheek.

There’s no reference in the newspaper as to how long the alligator lived, but there also wasn’t a long list of missing children from town a few years later.

Andrew Sefton died in 1887.

Though the Catoctin Wildlife Preserve and Zoo has a large alligator swamp, the alligators can’t remain there year round. Each year, the zoo features a Gator Round Up in late October or early November. Visitors can come and watch the zoo keepers collect the alligators and transport them to their winter quarters.

September 22, 2015

Cracker Jack continues to hit a homerun with baseball fans

Cracker Jack has delighted children for more than a century as they dig into a box, or nowadays, a bag of the caramel-coated popcorn and peanut treat searching for the prize inside. It’s in baseball stadiums across the country where the snack truly stands out, though, as thousands of fans sing out “Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack!” as part of baseball’s unofficial anthem, Take Me Out to the Ball Game.

Cracker Jack has delighted children for more than a century as they dig into a box, or nowadays, a bag of the caramel-coated popcorn and peanut treat searching for the prize inside. It’s in baseball stadiums across the country where the snack truly stands out, though, as thousands of fans sing out “Buy me some peanuts and Cracker Jack!” as part of baseball’s unofficial anthem, Take Me Out to the Ball Game.

“So what’s Cracker Jack’s secret?” Susan Feeney asked in her 2002 NPR report. “Three little words: toy surprise inside. One of the main ingredients that has helped Cracker Jack make a lasting impression, not to mention one of the first things that kids will look for on popping open a box, is the prize.”

The earliest version of Cracker Jack was introduced at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. “Candied Popcorn and Peanuts” was the creation of Frederick and Louis Rueckheim. It wasn’t an instant hit.

“People at the World’s Fair didn’t like the stickiness and the hardness of the early Cracker Jack,” wrote Linda Stradley, author of What’s Cooking America. “So Louis made a formula that made a great molasses coating that was crispy and dry. This secret formula is still a secret in the Cracker Jack Company today.”

Jim Davis, who has written two books about Cracker Jack prizes and prize collecting, said the World’s Fair story may not be entirely accurate. “Documentation says just the opposite; the Rueckheims were not listed among a detailed and comprehensive list of World’s Fair vendors. They could have been outside the gates, I suppose,” he says.

While coming up with the new recipe took time, coming up with a name took three years. According to the Odebolt Chronicle Progress Edition, a company salesman and Frederick were sampling the latest batch of the popcorn confection, when the salesman said, “That’s a cracker jack!”

“Why not call it by that name?” Frederick said.

“I see no objection,” the salesman said.

“That settles it then.”

And Cracker Jack was born.

The name, along with the slogan, “The More You Eat, the More You Want,” was copyrighted later that year and has been used ever since.

H.G. Eckstein joined the company in 1896 after he came up wax packaging that kept the popcorn from sticking together in one large clump and ensured freshness. This expanded the market for Cracker Jack tremendously since it could be shipped much further away. “In 1902, Cracker Jack was featured in the Sears catalog which meant that even individuals without access to a large city grocery store could order the product through the catalog and when it arrived it would be fresh,” Jim Trautman wrote in his article, “Crackerjacks and Those Wonderful Prizes.”

Cracker Jack’s big competitor in the early 20th century was Checkers. Checkers’ edge was that it offered prizes in each box. At the time, Cracker Jack offered coupons that could be redeemed for premiums. “You could save up the coupons and redeem them for big items like furniture and appliances,” says Harriet Joyce with the Cracker Jack Collectors Association.

Such premiums appealed to adults, though, and the bulk of the Cracker Jack market was children. In 1912, the Rueckheims copied a good idea and began offering their own prizes. They improved on the idea, though, by offering the prizes in series to encourage repeat business. That, plus a better product, allowed Cracker Jack to overtake Checkers in sales and eventually buy the company that made the popcorn treat.

As America entered World War I, expressions of patriotism could be seen everywhere. Cracker Jack introduced the red, white, and blue stripes to its boxes and created a patriotic mascot.

F.E. Ruhling, general sales manager for F.W. Rueckheim & Bros., wrote in the April 7, 1921, issue of Printer’s Ink, “It was entirely logical, therefore, that the trade character which we created should be a boy, jovial, happy, his arm full with three packages of his favorite. It is a trade character designed to appeal to children to work its way into their memory and make friends of them. And because every boy should have his dog for a pal, we gave the Cracker Jack boy his Bingo—a hybrid pup of questionable pedigree, but just the sort that every boy loves.”

The model for Sailor Jack is said to be Robert Rueckheim, Frederick’s grandson.

“I’ve seen a picture of Robert in the white sailor suits that were popular at the time,” Joyce said. “He was a blond-haired boy, but he didn’t look anything like Sailor Jack.”

That’s probably just as well since Robert died from pneumonia in 1920 at the age of 7.

Bingo is said to have been based on a stray dog Eckstein had adopted named Russell. Russell died in 1930.

The initial Sailor Jack advertising campaign in 1918 was followed by consumer testing to see if they both liked and remembered Sailor Jack and Bingo. Due to an overwhelming positive response, Sailor Jack and Bingo were added to the packaging a year later, according to Ruhling.

Cracker Jack continues to be popular today, though it has gone through a couple of corporate changes and has been owned by Frito-Lay since 1997.

You can even find collectors clubs made up of people with a passion for collecting the different prizes that Cracker Jack boxes have hidden over the years. Some of them can be worth thousands of dollars, depending on their rarity. Trautman wrote that the Chicago office of Cracker Jack kept in a vault at least one of every item ever manufactured.

Cracker Jack also remains available in every Major League Baseball stadium, where it can sell more than 1,000 bags a game, depending on attendance. When the New York Yankees tried to change the popcorn treat in their stadium, fans were outraged, and within two months Cracker Jack was back. Yankees’ chief operating officer, Lonn Trost, said at the time, “The fans have spoken.”

September 17, 2015

LOOKING BACK 1953: CIA doses men with LSD at Deep Creek Lake (Part 2)

President Ford meeting with members of the Olson Family.

The doorman at the Statler Hotel in New York City had taken a break early around 2:30 a.m. on the morning of November 28, 1953, to go for a drink at the nearby Little Penn Tavern. As he turned a corner, he saw something falling through the air.

“It was like the guy was diving, his hands out in front of him, but then his body twisted and he was coming down feet first, his arms grabbing at the air above him,” the doorman told Armond Pastore, the hotel’s night manager, according to H. P. Albarelli Jr. in A Terrible Mistake.

The body hit a wooden partition shielding work being done of the hotel and then the sidewalk. Frank Olson was dead.

A week and a half earlier, Olson had been unknowingly dosed with LSD while staying at a cabin at Deep Creek Lake. Once he discovered what had happened to him, it had changed his life, albeit for a short time.

The investigation by the CIA, which Olson worked with as part of Camp Detrick’s Special Operations Unit, found that Olson had died as “the result of circumstances arising out of [the Deep Creek Lake] experiment,” and there was a “direct causal connection between that experiment and his death,” according to the CIA’s general counsel report, according to the Baltimore Sun.

Although these conclusions had been reached within two weeks of Olson’s death, his family was only told that he had died in the course of his work. This allowed the Olson family to collect federal death benefits, while the official results of the death investigation remained classified.

More than 20 years later, a presidential commission investigating CIA activities inside the U.S. found that an Army scientist had fallen to his death from a hotel room in New York after the CIA had given him LSD in 1953. The Olson family confronted Vincent Ruwet, Olson’s division chief and friend, who admitted that the scientist was Frank Olson.

The family then started on a campaign to fully find out what had happened. President Gerald Ford invited the family to the White House and apologized for the death. The family also received a $750,000 settlement from the government.

However, Olson’s sons still weren’t satisfied that they knew the truth. They had their father’s body exhumed in 1994. A modern autopsy found that Olson had suffered a blow to the head before he fell from his hotel window. According to the autopsy report, the wound was suggestive of a homicide.

“The Manhattan district attorney’s office opened a homicide investigation in 1996. While they were unable to bring charges, they changed the official cause of death from ‘suicide’ to ‘unknown’,” The Baltimore Sun reported.

His family filed a lawsuit against the government in 2012, claiming that the CIA is still holding back files about Olson’s death.

“The evidence shows that our father was killed in their custody. They have lied to us ever since, withholding documents and information, and changing their story when convenient,” said Eric Olson told The Business Insider. The lawsuit was dismissed in 2013 when a judge ruled that it had been “filed too late and is barred under an earlier settlement,” according to Bloomberg Business.

Will the full truth about what happened to Frank Olson ever be known? It remains to be seen how the journey that began in a cabin by the lake will end.

September 10, 2015

LOOKING BACK 1953: CIA doses men with LSD at Deep Creek Lake (Part 1)

Dr. Frank R. Olson, a former biochemist on July 10, 1952 at Fort Detrick, allegedly committed suicide in 1953, when he jumped or fell from the tenth floor of a New York building. Olson’s family is suing the CIA in regard to the death. (AP Photo)

Two bottles of Cointreau sat on the table in front of Frank Olson. Both were open. Both were the same. He reached out for one of the bottles to pour himself an after-dinner drink. He was relaxing in a cabin with other men who had been forced to attend a three-day retreat at Deep Creek Lake from 11/18-20.

He hadn’t wanted to attend. He was having doubts about the ethicality of his work. He didn’t need to about the results of the work in which he was involved at Camp Detrick, in Frederick. He needed to think and clear his mind.

He knew the men he was sharing the large cabin on the lake with. They were members of the Special Operations Division and the CIA. Vincent Ruwet, Olson’s division chief and friend, had picked him up at his house and they had driven west to find this somewhat isolated cabin. It was a large, two-story rental cabin, off of Route 219 about 30 yards from Deep Creek Lake and 100 yards from the nearest neighbor.

The invitation to the “Deep Creek Rendezvous” said that a cover story had been given for the meeting. “CAMOUFLAGE: Winter meeting of script writers, editors, authors, lecturers, sports magazines.”

Olson believed they were there to talk about the joint projects of the Special Operations Division and CIA involving things like biological warfare and using drugs for mind control.

Unbeknownst to Olson, this was also a camouflage story to get him and others to the cabin for an experiment.

The men enjoyed a hearty dinner on Thursday, November 19, and then settled down in the cabin’s living room for after-dinner drinks. Robert Lashbrook, a CIA employee and one of the attendees, poured drinks for eight of the men present. He served the drinks and then poured himself and Sidney Gottlieb drinks from a separate bottle, although there was still liqueur in the first. If it struck anyone as odd or if anyone even noticed, no one remarked on it. Olson took the drink offered him. It was a simple choice, but one that would cost him his life.

He drank the Cointreau and then lost himself in his own thoughts. Sometime between then and Friday afternoon, Olson and the men were told their drinks had been dosed with LSD, according to the Church Committee report.

When Olson returned home that evening, his wife, Alice, “sensed something was wrong the moment he walked in the door. There was a stiffness in the way he kissed her hellow and held her. Like he was doing something mechanical, devoid of any meaning or affection,” H. P. Albarelli wrote in A Terrible Mistake.

Olson’s thoughts now were definitely elsewhere. Later that evening, he admitted to her, “I’ve made a terrible mistake.”

On Monday morning at 7:30 a.m., Olson was waiting for Ruwet when he arrived. Olson admitted he doubts about the work he was doing and said that he wanted to resign.

Olson told his wife later, “I talked to Vin. He said that I didn’t make a mistake. Everything is fine. I’m not going to resign.

The next day, Ruwet and Lashbrook convinced Olson to see a psychiatric doctor in New York. Actually, he was meeting with Harold Abramson, an allergist-pediatrician, who was working with the CIA.

Lashbrook and Olson shared a hotel room on the 13th floor of the Statler Hotel. Early in the morning of November 28, a loud crashing noise woke him up. According to the CIA, Olson threw himself out of the window, committing suicide.

The truth turned out to be something far darker and disturbing.

September 3, 2015

Battlefield Angels: The Daughters of Charity in Missouri During the Civil War

A Daughter of Charity provides care to a wounded soldier during the Civil War.

No one would look at a Daughter of Charity and see the steel in their personalities that gave them the ability to venture where women rarely went in the 1860’s. They ran schools, among which was St. Philomena’s School in St. Louis. They ran DePaul Hospital in St. Louis, which began as the St. Louis Mullanphy Hospital in 1828.

The latter was frowned on. Nursing wasn’t considered a suitable profession for women. Nursing in public hospitals was often done by other residents of the hospital or the poor. No formal training program existed.

That way of thinking began changing in the 1850’s, though. The French Daughters of Charity had served as battlefield nurses caring for French soldiers during the Crimean War. Their service had been so exemplary that many people began looking at the American Daughters of Charity and wondering if they could do the same thing once the Civil War began.

As the United States broke apart, Daughters of Charity from Emmitsburg found themselves serving soldiers in both the Union and Confederacy.

Father Francis Burlando and Mother Ann Simeon visited St. Philomena’s in 1861. Foreseeing that the sisters in Missouri might be called on to serve as nurses as they were in other states, they left directions for how the sisters in Missouri should handle the request when the time arose.

Catholic sisters and war

Nearly 700 Catholic sisters from 22 orders provided some sort of service during the Civil War. The Daughters of Charity provided the largest number—around 300—to serve in the war.

“The country had only 600 trained nurses at the start of the Civil War. All were Catholic nuns. This is one of the best-kept secrets in our nation’s history,” Civil War chaplain Father William Barnaby Faherty once said.

Though the American Daughters of Charity had been in existence for 52 years by 1861, their mother organization in France has existed since 1617. Even before the Civil War, the Catholic sisters’ future was tied to war. Not long after their founding, Founder Saint Vincent de Paul told the sisters, “Men go to war to kill one another, and you, sisters, you go to repair the harm they had have done… Men kill the body and very often the soul, and you go to restore life, or at least by your care to assist in preserving it.”

The American Sisters of Charity started gaining experience in health care when they took over the administration of the Baltimore Infirmary in 1823. Their success with the care of the sick in the hospital led to them opening the first hospital west of the Mississippi River, St. Louis Mullanphy Hospital. They gained experience working with victims of violence, accidents, yellow fever and cholera. As their reputation grew as nurses, they opened additional hospitals and they were asked to assume the administration and nursing duties of others.

These varied experiences in dangerous surroundings became the training ground for what they would face in the war. In doing so, they also became the only source for trained nurses, according to Sister Mary Denis Maher in her book, To Bind the Wounds: Catholic Sister Nurses in the U.S. Civil War.

An old postcard of the St. Louis Mullanphy Hospital in Missouri. The Daughters of Charity started the hospital before the Civil War.

In Missouri

On August 12, 1861, Union Major General John C. Fremont “desired that every attention be paid to soldiers who had exposed their lives for their country, visited them frequently, and believing that there was much neglect on the part of the attendants, applied to the Sisters at St. Philomena’s School, St. Louis, for a sufficient number of sisters to take charge of the hospital, promising to leave everything to their management,” according to the Daughters’ Annals of the Civil War. Because of the reputation of the Daughters of Charity, he promised he would leave the management of the hospital as well as the care of the sick and wounded in the hands of the sisters.

Twelve sisters from St. Philomena’s went to the Military Hospital House of Refuge in the suburbs of St. Louis. The sisters took charge of the hundreds of patients in the wards and whatever related to the sick and wounded. Peter Kenrick, Archbishop of St. Louis, sent a chaplain to say daily Mass for them. It soon became the primary location to send wounded Confederate POWs who were brought up the Mississippi River on hospital steamboats. The Union wounded were sent to City Hospital.

At first, the sisters were a wonder to behold because of their strange dress and some patients asked them if they were Freemasons. The patients were grateful for the fine care they received, and because of that, they gave the sisters their respect and cooperation.

Women from the Union Aid Society visited the soldiers every other day. These women grew to admire the peace that reigned in the wards overseen by the Daughters of Charity and found the patients “as submissive as children,” George Barton wrote in Angels of the Battlefield.

St. Louis was inundated with wounded soldiers after battles. Hospital steamboats would pick up patients from battlefields, treat them and take them to St. Louis for further treatment and recuperation there. More than 800 wounded were known to arrive in the city in a single day and the Daughters of Charity cared for many of them.

Often when the soldiers returned to their regiments, they told other sick or wounded soldiers, “If you go to St. Louis, try to get to the House of Refuge Hospital. The Sisters are there, they will make you well soon,” according to Notes of the Sisters’ Services in Military Hospitals, 1861-1865.

Sisters from St. Louis also visited Jefferson Barracks Hospital, nine miles from the city. The primary duty of the military camp would shift from training soldiers to saving their lives by 1862 when it became a Union hospital with more than 3,000 beds.