James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 22

June 12, 2015

Frederick County’s (Md.) last slave, part 1

Ruth Bowie, “Miss Ruthie”, in the 1950’s.

To most people, Ruth Bowie, or “Miss Ruthie” as she was called, was just a friendly old lady with a sense of humor and a sweet tooth. What they didn’t realize was that she was also a historical figure in the county.

When she died in 1955, she not only was the oldest person in Frederick County (anywhere from 105 to 110 depending on which account was used), she was also the last person in the county who had been born into slavery.

As old as…

No one made an official record of Ruth Brown’s birth in the mid-19th Century. The 1900 U.S. Census listed her as 40 years old, but by the 1920 census, she had aged 25 years.

“Nobody knows just how old Miss Ruthie is, least of all Miss Ruthie herself,” Betty Sullivan wrote for the Frederick Post. Sullivan also noted that Ruth couldn’t remember ever celebrating a birthday as a child.

She is believed to have been born on the Asbury Mullinix Farm in Montgomery County. However, Kay Mehl wrote in the Sun Magazine in 1955 that Bowie was born elsewhere and “’just a toddler’ when sometime before the war she was sold in Montgomery County to a family named Mullinix.”

The Asbury Mullinix farm was located at Long Road off Long Corner Road in Damascus. It was part of a small community called Mullinix Mill, but the buildings burned down long ago.

Ruth’s parents were Wesley and Letha Brown.

Marilyn Veek, a research assistant at the Maryland Room in the C. Burr Artz Library, found the description of Asbury Mullinix’s slaves in the 1850 and 1860 Slave Schedules. In these documents, slaves are listed by their description and owner rather than their name.

In 1850, Mullinix owned seven slaves, including female aged 28 years, 14 years and 6 months. On the 1860 Slave Schedule, he owned nine slaves, including three females ages 11, 8 and 4.

The Asbury Mullinix Farm where Miss Ruthie was born and lived. Family stories say that the little girl on the left behind the fence is Miss Ruthie.

“Since Ruth Bowie’s obituary indicates that she may have been born between 1845 and 1850, it is theoretically possible that she could be the female slave aged 6 months in the 1850 and the female slave aged 11 years in 1860,” Veek wrote in an e-mail.

Veek also noted that Ruth’s parents were listed in the regular 1860 census, which implies that they have may have been freed. That census also only lists them as having a single daughter, 1 year old, named Ann.

“One possibility is that they had been freed by Asbury Mullinix, but that their older children had not, and remained as slaves on his farm,” Veek wrote.

Bob Hilton, a great-great grandson of Asbury Mullinix, suggested another possibility. The Browns may have been freed slaves who still worked for the Mullinixes.

“Asbury had a habit of freeing slaves at 30 years old,” Hilton said. “They just never left the place.”

This had to do with Mullinix’s view of slaves. Hilton has a set of letters exchanged between Mullinix and a doctor in Virginia. In the letters, the doctor argues that slaves aren’t even human while Mullinix says that, yes, they are human, but they are like children who need to be taken care of.

The Browns were still living in the same area in the 1870 census. They are listed as having three daughters, Ellen, Mary and Susan. Ruth Brown doesn’t appear in the 1870 census associated with them.

June 5, 2015

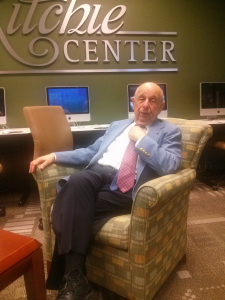

The Return of a Ritchie Boy

WWII veteran Guy Stern returns to Fort Ritchie to speak about his experiences there. Photo courtesy of the author.

Cascade may be a small community nestled in the mountains, but what happened there 75 years ago helped changed the world.

Guy Stern fled Nazi Germany in 1937 as a young man of 15. He left behind his parents and two siblings.

“I made efforts to get the papers for my family to emigrate and I almost succeeded, but in the end it did not work,” said Stern in an interview with the Waynesboro Record Herald. Stern’s family eventually perished in the Holocaust.

Meanwhile, Stern attended St. Louis University and was drafted into the U.S. Army in 1942. Only a few months after his basic training in Texas, he received secret orders to transfer to Camp Ritchie in 1943.

Because of his German heritage, he had been selected as part of a military intelligence training program. Using the knowledge of the German language and culture that men like Stern had, they were trained in interrogation, psychological warfare, and counter-intelligence. About 9,000 mostly Jewish soldiers went through the training and became known as The Ritchie Boys.

Stern was trained in interrogation techniques, the evaluation of enemy documents, psychological warfare, German propaganda and ancillary skills that every soldier needs. The training could also be physically demanding with long, nighttime marches.

“I earned by Ph.D. at college, but nothing I had done at college was as difficult or intense as training at Camp Ritchie,” Stern told the Catoctin Banner.

However, Stern was also able to appreciate the beautiful mountain setting. He enjoyed swimming and canoeing in the lake.

The training at Camp Ritchie lasted for three months. His group was then sent to Louisiana for maneuvers that tested whether they had learned the skills they would need in Europe. Stern and other Ritche Boys were then shipped across the Atlantic. They initially landed in Birmingham, England.

While in England, the Ritchie Boys participated marginally in the D-Day invasion planning. Stern said that they were in charge of how prisoners captured in the invasion would be handled. Once the invasion began, the Ritchie Boys landed three days later to begin their prisoner interrogations.

“Within the first half-hour of being on the beach we began interrogating people and tinkering with psychological warfare,” Stern told the Record Herald.

One of their tactics was to play on the fears of German prisoners. When the Ritchie Boys discovered that German soldiers feared being turned over to Russians, Stern began dressing up in the uniform of a Russian officer. Another Ritchie Boy would lead the prisoner into a tent decorated with Russian posters and mementos. Stern would then interrogate the prison in character as a German.

One of Stern’s coups was when an Austrian deserter gave him a diary that the deserter had kept from the Battle of the Bulge to his capture at the Rhine River. Stern said that between his interrogations and the diary, he believed that the information was correct and useful. It contained information on German morale, plans for troop retreats and hints to the dispersion of other units.

“We could use the information to form the basis of how we directed our propaganda,” Stern told the Catoctin Banner.

Stern returned to Camp Ritchie on Sept. 21, 2013, and found it very different at least until sunset. At that time, Lakeside Hall returned to look very much the way it had when it had been an officer’s club during World War II.

As part of the Sunset on the Mountain event, the hall was given a period makeover. USO Canteen style food was served and 1940’s music played. Sunset on the Mountain also featured an auction with Fort Ritchie and World War II experiences including a ride in an open-cockpit PT-19 trainer aircraft courtesy of the Hagerstown Aviation Museum, a catered dinner at Fort Ritchie’s famed Castle, and autographed memorabilia.

The proceeds from the event benefitted the Fort Ritchie Community Center, which is seeking to get a permanent exhibit in the center that features the Ritchie Boys and Camp Ritchie’s history.

May 28, 2015

It’s an odd country that we live in

My mother-in-law gave my son The United States of Strange for a present one year. I think I read it more than him. It’s filled with lots of odd facts. If you love Mental Floss, you’ll love this book. Anyway, here’s some weird history that I pulled from the book.

My mother-in-law gave my son The United States of Strange for a present one year. I think I read it more than him. It’s filled with lots of odd facts. If you love Mental Floss, you’ll love this book. Anyway, here’s some weird history that I pulled from the book.

During the Civil War, Frank C. Armstrong was the only general officer to fight on both sides, as a captain for the Union army and a brigadier for the Confederacy. Talk about a split personality!

As of 2011, the 10thS. president, John Tyler, who was born in 1790 still has two living grandchildren. I’m still trying to figure out how that is possible.

Until 1977, the U.S. nuclear launch code was 00,00,00,00,00,00,00. This makes those people whose computer passwords are “Password” look like geniuses.

Thomas Edison held 1,093 patents during his lifetime. As a side note, the first copyrighted film in the U.S. was Edison’s assistant sneezing. I wonder if it made as much as The Avengers?

In 1989, a man bought a painting for $4 at a flea market. When he got it home, he found a piece of parchment wedged into the frame. He pulled it free and opened it to discover that he had what turned out to be an original copy of the Declaration of Independence worth $8 million. My son goes to yard sales and only brings home broken stuff that we wind up throwing out.

July 1744, British colonists paid the Iroquois Indians $2,400 for land that it turns out the Iroquois had no right to. This led to a war between the colonists and the Native Americans who did own the land. I guess that was payback for the Dutch getting Manhattan for $24.

When returning from the moon, Buzz Aldrin, Michael Collins, and Neil Armstrong had to go through customs. I wonder if they had to fill out forms declaring why they visited the moon and if they had anything to declare.

Anyway, The United States of Strange is a fun book that claims to have “1,001 Frightening, Bizarre, Outrageous Facts” between the covers. I know I’m amazed each time I read a couple pages.

May 24, 2015

Saving the Marine Corps

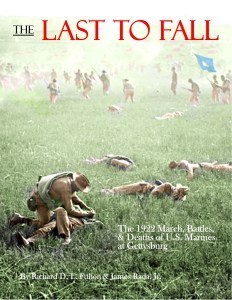

This is a short excerpt from The Last to Fall: The 1922 Marine March, Battles, & Deaths of U.S. Marines at Gettysburg.

The Marines had fought valiantly in World War I like in the Battle of Belleau Wood in France. After the deadly fighting there to drive the entrenched German troops from Belleau Wood, Army General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, said, “The deadliest weapon in the world is a Marine and his rifle.”

The Marines had fought valiantly in World War I like in the Battle of Belleau Wood in France. After the deadly fighting there to drive the entrenched German troops from Belleau Wood, Army General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, said, “The deadliest weapon in the world is a Marine and his rifle.”

However, that didn’t stop Pershing and others from wanting to disband the Marine Corps after the war had been won.

“Right after World War I, when John A. Lejeune was appointed commandant of the Marine Corps, there was a push by General Pershing and President Wilson to have the Marine Corps abolished,” said Gunnery Sergeant Thomas Williams, executive director of the United States Marine Corps Historical Company.

It wasn’t the first time such an action had been considered, nor would it be the last. However, Major General Lejeune was a Marine through and through, and he wasn’t going to go down without a fight.

Lejeune understood that this was a political battle that would be fought on the battlefield of public opinion. He devised a campaign to raise public awareness about the Marine Corps just as the government had rallied public opinion behind the troops during the war.

A number of things evolved from this effort. Celebrating the birthday of the Marine Corps as November 10, 1775 was part of the public relations push by the Marine Corps. Also, elements of the Marine uniform were tied to iconic battles or moments of Marine Corps history.

Gen. Lejeune also wanted to improve the skills and abilities of the Corps by applying lessons learned from WWI to introduce new tactical doctrines. He realized that he could do this and use it as a means of increasing public awareness about the Marine Corps.

“Instead of going to obscure places to conduct war games and learning lessons learned and learning how to integrate armor, artillery, and aviation into war fighting, he would do it at iconic places and put the Marines out in front of the public,” Williams said.

At the time, the national military parks, such as Gettysburg, were still under control of the U.S. War Department, which meant the Marines could use the parks as a training ground. Lejeune chose to do just that with a series of annual training exercises, which commenced in 1921.

May 14, 2015

A policeman, an owl, and a cow go out one night…

An old postcard view of Bedford, Pa., where Officer Young met an owl and a cow one night in 1950.

It sounds like the opening line for a joke. A policeman, an owl, and a cow went out one night. However, while not funny, it is certainly odd.

Bedford Police Officer James Young was station near the corner of Pitt and Julianna streets in the town one early morning in April 1950. Around 2 a.m., he watched a large owl dive out of the night school and crash into the window of Murdock’s Jewelry and Gift Shop.

The store had been around since 1910 when J. F. Murdock took over the J. W. Ridenour dtore. “His gifts are especially well known for their unique and pleasing qualities,” the Bedford Gazette said of Murdock’s.

As Young watched the large owl flopping around groggily on the sidewalk, “It occurred to Officer Young that owls are birds of prey with a bounty on their heads,” the Cumberland Evening Times reported.

He started across the street with the intent of subduing the owl and turning it in for its bounty. Before he could reach it, the owl recovered and took to the air. It flew across Julianna Street and landed on top of the scales in front of Murphy’s Store.

“Unsheathing his night stick, Officer Young slowly approached, shining his flashlight in the bird’s eyes to hold its attention,” the Cumberland Evening Times reported.

A quick hit with the night stick brought the bird down. Young stretched out the owl’s wings and guessed the wingspan was at least four feet wide.

Because of the size of the owl, Young tried to get help from a nearby taxi driver to help him load the owl into his vehicle.

“But as he and an assistant started to return they saw the durable bird prop itself up, heave into the air and make off in the direction of the Monument,” the Cumberland Evening Times reported.

And that was the last that Officer Young saw of the owl, but the cow’s story was just beginning. It came ambling down West Pitt Street from the direction of the Ford Garage. Officer Young saw it and went to try and lead it somewhere, of course, he wasn’t sure where that “somewhere” would be. The cow, for its part, had its own ideas of where it wanted to go and it resisted Young’s efforts to move it in a different direction.

At times, it was uncertain as to who was leading whom, but Young finally managed to push the cow into a fenced in yard and closed the gate behind it.

Young was wondering what to do with a cow when the police call sounded. He answered it and the dispatcher told him that a trucker had passed through Bedford carrying seven cows in his trailer. Upon reaching his destination, the trucker discovered he only had six cows. Young looked over at his captured cow and assumed that it must have fallen off somewhere along the journey without being injured.

It was nearly sunrise by the time he managed to return the stray cow to the grateful trucker.

“His owl-bounty had flown away and he was weary from his tussle with both bird and beast. ‘But,’ he said, as he related the story later, ‘at least it was an unusual night,’” the Cumberland Evening Times reported.

May 7, 2015

A coal town collapse, part 3

Help had arrived at Shallmar, Md. Trucks began arriving daily, braving the steep, narrow roads to reach the isolated coal town. A Baltimore meat packing company sent a load of fresh beef. The Maryland Jewish War Veterans collected toys. The Amici Corporation in Baltimore sent $50 to the Oakland Chamber of Commerce to purchase candy for the children of Shallmar. Plus, Amici employees raised another $1,000 for the town in general.

Help had arrived at Shallmar, Md. Trucks began arriving daily, braving the steep, narrow roads to reach the isolated coal town. A Baltimore meat packing company sent a load of fresh beef. The Maryland Jewish War Veterans collected toys. The Amici Corporation in Baltimore sent $50 to the Oakland Chamber of Commerce to purchase candy for the children of Shallmar. Plus, Amici employees raised another $1,000 for the town in general.

The Baltimore American Legion collected so much food and clothing that it filled a room at the War Memorial Building. Among the donated items was 300 pounds of bacon, 250 loaves of bread, 200 quarts of milk, cases upon cases of canned goods and groceries, 100 pairs of shoes, 20 men���s overcoats, 12 women���s fur coats and blankets, not to mention toys for the children.

From New York City, the Save the Children Federation said that it would be sending toys and other needed things to the town. The Cumberland local of the United Brewery Workers of America also began raised money. Cumberland dairies donated milk and bakeries donated bread.

Shallmar even made international news when the London Times interviewed Andrick for a story. Letters arrived from other European cities like Paris with words of concern for Shallmar���s residents.

A photographer took a shot of two-year-old Jean Ann Crosco sitting amid a pile of shoes being distributed. She was crying because none of them fit her. Numerous newspapers all around the world ran the picture and donations poured in specifically for Jean Ann. About a week after the photo was published, Jean Ann���s mother told The Iola Register, ���We have heard from every state in just a week. The kind people sent her dresses and other pretties. And she had about $200 in money gifts. And Jean Ann has forty���yes, forty���pairs of shoes.���

The picture spurred A. K. Rieger, president of Gunther Brewing Company in Baltimore, to buy all of the children in Shallmar a new pair of shoes.

On Dec. 21, the senior class at a Cumberland Catholic girls��� school, cancelled its own Christmas party to throw one for the children of Shallmar in the school. Two days later, the United Paper Workers Union Local 67 came to town to throw the children another party.

The Cumberland Optimist Club alone had delivered more than 15 tons of food and clothing to the town by the middle of December and it was only one organization of dozens that was delivering food.

As Christmas Day approached, the downstairs of the J. Paul Andrick home filled with boxes and bags of letters and postcards; most of them with cash and checks in them. On the Friday before Christmas, 2,000 pounds of mail arrived in Shallmar.

A week before Christmas, the Shallmar Relief Committee decided that since the town���s residents had been blessed by so much kindness that they would be just as generous. The committee sent out food and clothing to help another 70 families in the region who were in just as bad a shape as families in Shallmar had been. Some got money, some got clothing and they all got food.

���Today with $5,000 on deposit to their credit in a nearby bank, with tons of canned food piled up in their schoolhouse and more toys for their children than they know what to do with, the people of Shallmar have a realization of the Christmas message of ���good will to men,��� George Kennedy wrote in The Washington Star.

On the Friday before Christmas, the members of the Shallmar Relief Committee filled the school classrooms with the items that had been held back from distribution. Children were allowed into the school to select one toy, one novelty and one book. They were stunned at the abundance that confronted them and were hesitant to pick anything up. The girls, especially, were slow in selecting their dolls. They would look at the dolls without touching them and once their decision was made, they would pick up their doll and hug it.

Of all of the children who came to the toy shop that day, only one returned. Six-year-old Elaine Paugh came back about an hour after she had finished her selections. She quietly told Andrick that her mother had told her to return the very nice doll that she had selected for herself. She was obviously fighting back tears as she handed the doll to Andrick.

Andrick told her to go ahead and select another doll, but he knew something that Elaine didn���t. Her mother had picked out a beautiful doll for her on Friday evening and thought that another little girl should get the nice doll that Elaine had picked out. Elaine would be sad for only a day.

That evening, Paul dressed up as Santa Claus and delivered bags of candy, nuts and oranges to each of the families in Shallmar.

Charlotte Crouse and her brother were fighting that evening and too excited about the coming of Christmas to go to bed. Her mother finally had enough and told them, ���If you don���t stop fighting, Santa Claus won���t come.���

At that moment, Charlotte looked up and saw Andrick outside the window in the living room. Of course, she thought she was seeing Santa Claus. She quickly stopped fighting with her brother and was on her best behavior for the rest of the night.

The next morning Charlotte got the doll for Christmas that her parents had picked out for her.

At Christmas morning church services, preachers announced that children from surrounding towns would be welcome to come and pick out their own toys at the Shallmar School. The relief committee had decided that it wanted to make sure that all of the gifts were shared with other children who might not have a Christmas otherwise.

Donations to Shallmar and its residents continued flowing into town even after Christmas. With hunger only temporarily eased by what grew to an estimated $7,000 in cash and $30,000 in food, toys, clothing and other items by early 1950, Andrick and the Shallmar Relief Committee turned their attention to long-term solutions for the town���s problems. The money lasted until the account was closed in May1952.

April 24, 2015

A coal town collapse, part 2

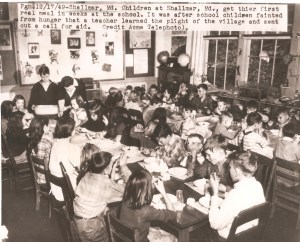

��On December 8, 1949, residents picked up The Republican to read: ���Shallmar Residents Are Near Starvation, Urgent Appeal Made For Food, Clothing and Cash.��� It was a front page story under the masthead of the newspaper.

��On December 8, 1949, residents picked up The Republican to read: ���Shallmar Residents Are Near Starvation, Urgent Appeal Made For Food, Clothing and Cash.��� It was a front page story under the masthead of the newspaper.

Mine closings and poverty were nothing new to the region, but the fact that it was so bad that children were fainting from lack of food and others not able to attend school because they didn���t have warm clothing was more than anyone with a conscience could handle.

Charles Briner, the Garrett County director of employment security for Maryland, was inundated with telephone calls that spanned the gamut from pleas for him to do something to help Shallmar to accusations that he was killing the miners.

The Oakland American Legion Auxiliary was quick to announce that it was starting a collection of clothes and food.

A Cumberland Evening Times reporter arrived in Shallmar on the day The Republican article came out. He interviewed residents for his own article, which ran the following day.

As Shallmar���s story spread, more and more letters filled Paul���s mail slot at the company store until finally all Paul was getting was a note from the postmaster and store manager, Baxter Kimble, saying to ask him for the mail.

The other person who started getting calls and letters was mine superintendent Howard Marshall. Reporters tracked him down in a Cumberland hospital recovering from minor surgery.

Marshall told reporters that he didn���t know when the mine would reopen. He seemed to have little sympathy for the plight of his miners and their families.

���I ain���t seen anyone starving yet,��� Howard told the reporters. His solution was that the county welfare system should take care of them. ���They pay enough taxes,��� he said.

However, he wasn���t totally unsympathetic. The company wasn���t trying to collect on its house rent or company store accounts. While the rent for the largest houses in town was only $12.60 a month, in some cases, rent hadn���t been paid for over a year.

��

A few days after the Cumberland Evening Times appeared, a large truck rolled into town filled with fresh vegetables, meat packed on ice, canned goods, milk, dresses, pants and shirts. So many people had been calling the newspaper office asking where they could make donations that newspaper collected donations and used a company truck to make the delivery.

Seven-year-old sandy-haired Bob Hartman���s eyes bugged out at all the food. Then he saw a set of new Levi overalls that looked like they would fit someone his size.

He told one of the men, ���I���d sure like to have them overalls.���

The truck driver looked at Bob and his threadbare clothes. ���We���ll see if we can���t get them for you.���

The man walked away. When he came back a minute later, he had the overalls in his arms and handed them to Bob. He ran home and tried them on, pulling the stiff material over his worn pants and shirt. The overalls weren���t a perfect fit, but it was good enough. He felt warmer without any drafts whipping through the holes in his pants. Though Christmas was still two weeks away, Bob felt like it was already Christmas morning.

It looked like Christmas had come early to the town. Unshaven miners smiled behind their whiskers, mothers and wives laughed as children grabbed at the clothing separated into piles on tables in the union hall. Finding something they liked, many children hurried home to try on the clothes. Others couldn���t wait that long and began pulling on sweaters over their summer shirts and trying on shoes. It was the first time in weeks that some of them had been warm. Each family also got enough food to last them a week.

With the town���s sudden abundance, Andrick called for a community meeting in the school to decide how to distribute the food. He also told the gathered crowd that more would be coming. The townspeople formed the Shallmar Relief Committee with Andrick as the chairman.

Relief efforts for the town got a big boost when CBS broadcaster Edward R. Murrow saw the story on the news wires and told the country about Shallmar on his Dec. 13 broadcast. More reporters, including Murray Kempton from the New York Post, started arriving in town to follow-up on the story of the town on the verge of starvation.

By the time The Republican article had come out, the Garrett County Commissioners had already decided to fund a hot lunch program for Shallmar School, a building without a kitchen or cafeteria.

The union hall in the school could be used as the dining hall, but there was no way to prepare the meals. The commissioners weren���t willing to pay for a school expansion and the kitchens in the houses in Shallmar were too small to prepare hot lunches for large groups. The solution was to cook the meals at Kitzmiller School, which was two miles away. The food was then dished out on plates that were covered and driven to Shallmar to be served while they were still hot.

With a plan in place, the commissioners allocated $1,200 to feed the students at Shallmar through the end of the school year. Andrick also allocated money that the town had been receiving to pay for the students��� portion of their lunches.

On Dec. 17, students sat down at two long wooden tables and had their first hot lunch in weeks, if not months.

April 20, 2015

The Legacy of Battle: Pennsylvania College in the Post-Civil War Era

Originally posted on The Gettysburg Compiler:

Originally posted on The Gettysburg Compiler:

by Meg Sutter ���16

For Parts 1 and 2 of this three-part series, see ���The Calm Before the Storm: Pennsylvania College in the Antebellum Period.��� and��������We will close . . . you know nothing about the lesson anyhow': Pennsylvania College during the War���

The war did not end with the Battle of Gettysburg, of course, and Gettysburg and Pennsylvania College were still impacted after the battle and the end of the war. In November 1863, David Wills, an 1851 graduate of Pennsylvania College, invited President Lincoln to give an address dedicating a National Cemetery to those who had died at Gettysburg giving their ���last full measure of devotion.��� Dr. William E. Barton in Lincoln at Gettysburg described November 18, 1863 as ���Gettysburg���s greatest night . . . John Hay and other gay spirits made a festive night of it. They had an oyster supper at the college, other re-freshments���

View original 1,147 more words

April 17, 2015

A coal town collapse, part 1

Betty Mae Maule was one of 60 students who attended the two-classroom Shallmar School in November 1949. When teaching principal J. Paul Andrick asked Betty Mae to write a problem at the board one day, the 10-year-old girl stood up at her desk and promptly fainted.

Betty Mae Maule was one of 60 students who attended the two-classroom Shallmar School in November 1949. When teaching principal J. Paul Andrick asked Betty Mae to write a problem at the board one day, the 10-year-old girl stood up at her desk and promptly fainted.

Betty Mae and her siblings hadn���t eaten anything all day. Their last meal had been the night before when the eight people in the family shared a couple apples.

This is how bad things had gotten in the little coal town on the North Branch Potomac River. What had once been the jewel of Western Maryland coal towns was dying.

Operating only 36 days in 1948, the Wolf Den Coal Corporation, which owned Shallmar, came into 1949 struggling in vain to stay open. The mine shut down in March, having operating only 12 days that year.

Shallmar���s houses had once been considered among the nicest homes for miners in the region. Now they needed a fresh coat of paint and more than a few were boarded up because they were no longer livable or needed.

The Maule family had six children. When Andrick explained to Walter Maule and his wife, Catherine, that he knew their children hadn���t eaten that day, Catherine���s explanation was simple: The mine had closed.

Miners had collected unemployment, but it hadn���t been much because the miners hadn���t worked much in recent years. Even that meager amount had stopped in August.

Albert Males, chairman of the United Mine Workers local relief committee, had then used the union treasury to issue small relief checks of $2 to $7 a week to families. He only had $1,000 to split among four dozen families so it hadn���t lasted long.

The Maules had been eating only apples that the children had found on the ground at a nearby orchard. Those had run out the day before, which is why the family hadn���t eaten that morning. It wasn���t the first time they had gone without breakfast lately either.

���My children have forgotten what milk tastes like,��� Catherine later told a reporter for the Cumberland Evening Times. They hadn���t had any meat or milk for four months.

Catherine assured Paul that they had managed to find enough cabbage and potatoes to get them through the next day. She was proud of this because, ���We sometimes don���t even have potatoes and cabbage,��� she said.

With the mine closed there were no jobs in Shallmar. Only three people in town had cars and families couldn���t afford the move.

Taking action

That night, Andrick started writing letters to anyone he could think of who might be able to help from the board of education to his U.S. senators. He also wrote to the county newspaper, The Oakland Republican hoping to let people know about Shallmar���s plight.

That night, Andrick started writing letters to anyone he could think of who might be able to help from the board of education to his U.S. senators. He also wrote to the county newspaper, The Oakland Republican hoping to let people know about Shallmar���s plight.

The next morning, Andrick had his wife make extra sandwiches for his lunch. He gave the sandwiches to the students he saw with nothing to eat at lunchtime, according to his son, Jerry. He not only gave the extra sandwiches away but his own lunch as well.

The men in Shallmar had tried to feed their families. They hunted each day, but came home empty handed. Many deer in Western Maryland were dying from a disease in 1949 reducing their numbers. Shallmar hunters only managed to bag four deer. The meat was appreciated, though.

���I never cared much for venison, but it was the first fresh meat in this house for three months,��� one woman told a reporter with the Portland Sunday Telegram and Sunday Press Herald.

John Crouse was one of the lucky hunters who bagged a deer in season, but it wasn���t enough to keep his family of six children fed for too long. The Crouse family ate one meal a day and on many days and that meal was potatoes and baked beans.

���It was the first time we had fresh meat in eight months,��� John���s wife, Dolly, told the Baltimore Sun.

April 1, 2015

Find out how the Marines would have fought the Battle of Gettysburg

The Last to Fall: The 1922 March, Battles, & Deaths of U.S. Marines at Gettysburg is now available for sale online and at stores.

The Last to Fall: The 1922 March, Battles, & Deaths of U.S. Marines at Gettysburg is now available for sale online and at stores.

Thomas Williams, executive director of the U.S. Marine Corps Historical Company, said, ���Every American is familiar with the iconic battle fought in Gettysburg during the American Civil War, some are even aware that two Marine officers and the ���Presidents Own��� Marine Band accompanied President Abraham Lincoln to Gettysburg in November 1863 to dedicate the National Cemetery there. However, few people are aware that 59 years later the US Marines would “reenact” the battle.

���In 1922, General Smedley Butler would march over 5,000 Marines from MCB Quantico, Virginia to the hallowed fields of Gettysburg. Conducted as a training exercise, but more importantly to raise public opinion and awareness, the Marines would travel to the National Battlefield and carry out many aspects of the original battle. Ultimately over 100,000 spectators would come to witness this monumental event.

���Authors Jim Rada and Richard Fulton have done an outstanding job of researching and chronicling this little-known story of those Marines in 1922, marking it as a significant moment in Marine Corps history.”

The 178-page book is 8.5 inches by 11 inches and contains more than 160 photographs depicting the march from Quantico to Gettysburg and the simulated battles on the actual Gettysburg battlefield.

���The march involved a quarter of the corps at the time,��� co-author Richard D. L. Fulton said. ���It was part PR stunt, but it was also an actual training maneuver for the marines.���

James Rada, Fulton, and Cathe Fulton (who served as a research assistant) searched through hundreds documents and photographs looking for the details of the march and battles, but the book was meant to tell a story. For that, they went hunting through lots of newspapers in order to piece together the stories of the marines on the march and the people they met along the way.

���What���s really fun is that the marines re-enacted Pickett���s Charge both historically and with then-modern military equipment,��� Rada said.

The event was also marred by tragedy when something happened to one of the bi-planes and it crashed into the battlefield killing the two marines flying it. The pilot, Capt. George Hamilton was a hero of World War I.

President Warren G. Harding and his wife, along with a number of military personnel, politicians, and representatives of foreign governments, stayed in camp on July 1 and 2 with the marines and witnessed some of the maneuvers.

The Last to Fall: The 1922 March, Battles, & Deaths of U.S. Marines at Gettysburg retails for $24.95 and is available at local bookstores, online retailers and ebookstores. You can purchase it from Amazon.com here.