James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 26

July 25, 2014

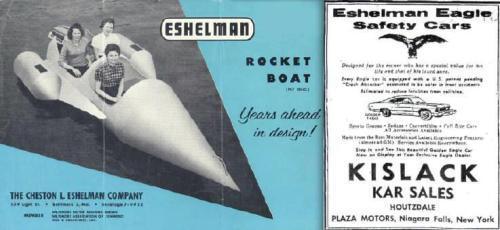

Mars adventurer builds “Rocket” boats and cars

As Paul Harvey used to say, “Here’s the rest of the story” about the Gettysburg man who tried to fly a plane to Mars.

People thought Cheston Eshleman, a Gettysburg High School graduate, was crazy when he tried to fly to Mars in a small airplane in 1939. Maybe they were right, but there’s a fine line between crazy and genius.

Eshleman’s flight of fancy cost him his pilot’s license, but it didn’t stop him from thinking about flying and how it could be done better. One of the things he thought about was how an airplane might be improved so that he could have had a better chance of flying further, although not necessarily in outer space.

One of his designs was called a “flying flounder” or “flying pancake” by people who saw it, but Eshleman called it his “flying carpet.” In 1942, the Gettysburg Times reported that the odd plane “has aroused the interest of Army and Navy officials.”

Eshleman, who was 25 years old, had been testing his new plane in Baltimore since January of 1942. By late July, it had flown successfully 62 times.

“A friend pilots the ship on its tests for Eshleman has been unable to fly since his license was revoked after a fishing boat picked him up at the end of his ‘Mars’ flight,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

Eshleman’s “flying carpet” was 24 feet long and 12 feet wide. It was made entirely of plastic except for some electronics and wiring. Eshleman and six other men had built the airplane in eight weeks at a cost of $5,000 (about $73,000 today). He told reporters that he believed that he could build a larger version of the plane in half the time.

“The wingless construction, he states, has reduced drag or wind resistance 30 per cent providing for speed increase. The aircraft, he asserts, retains normal lifting power, can land in a very small space, and will make 190 miles an hour when powered by a 130-horsepower motor. It has a normal tail assembly and a propeller in front,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

While most of the bugs had been worked out of the design by July, the maiden flight of the plane had been disappointing at best.

“The craft got a few feet off the ground, bounced back to earth, and caught fire. It looked like the end of an experiment which in a letter to President Roosevelt Eshleman had said would ‘cause all existing aircraft in the world to become historic,’” the newspaper reported.

Eshleman’s airplane designs were patented in 1943 and his start-up company began building light, commercial aircraft in Dundalk, Md.

After World War II ended, his attention seemed to shift from aircraft to other types of machinery. The Cheston L. Eshleman Company in Baltimore built lawn mowers, plows and garden tractors.

Then in 1953, his attention shifted again and he began building small, one-cylinder automobiles, golf carts, boats, and scooters. Though no longer building planes, he paid homage to his interstellar dream by calling his boat design, the “Rocket Boat,” which was built from surplus military aircraft wing tanks.

The one-cylinder, air-cooled, two-horsepower engine powered the car up to 15 mph and cost $295. It was sold as a child’s car while the adult car cost $395 and had a three-horsepower engine that could travel at 25 mph. The small cars featured battery-operated head and tail lamps, upholstered seats, and rocket emblems (an Eshleman trademark feature) on the flanks. The cars could also get 70 miles per gallon.

Eshleman ran an effective mail-order campaign to sell most of the vehicles. However, this proved a detriment when many people were disappointed at the small size of the cars, which were 54 inches long, 24 inches wide and 23 inches tall. They quickly returned the vehicles.

After a fire destroyed the Baltimore factory in 1956, the company moved to Crisfield, Md., and renamed itself the Eshleman Motor Company in 1959. It also started building slightly larger cars that were up to 72 inches long and 60 inches tall.

While the company continued building cars, Eshleman moved to Miami, Fla., and began working on new design for a front bumper. Eshleman called it a “crash absorber” and made it from a tire. It was impact resistant up to 15 mph.

Though he continued to invent and earn patents, Eshleman largely retired from the business world in 1967.

Eshleman died at age 87 in 2004, never having reached Mars, though he had certainly seen his dreams soar.

July 24, 2014

Much Better Historical Movies

My writer’s group just had a discussion about Son of the Morning Star and the consensus was that despite its flaws, it was the best of the Custer movies.

Originally posted on Practically Historical:

Originally posted on Practically Historical:

An earlier post pilloried poor historical dramas…this list contains superior efforts.

31 seconds to infamy

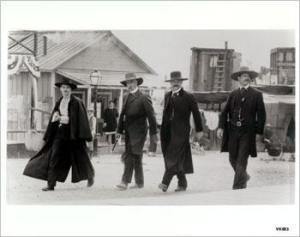

Tombstone-1993: No movie will ever accurately portray the life and character of Wyatt Earp, he’s not nearly likable enough; but Tombstone comes close to capturing the tumultuous two-year period the Earp clan resided in Southern Arizona. Kevin Jarre crafted a remarkably accurate and detailed script and was granted permission to direct the film. Shortly after filming began, studio hatchet men fired Jarre and stripped much of his work from the final product. The production values remained high featuring authentic costuming, gun play, and a detailed recreation of Arizona’s biggest boom town. Enough of Jarre’s script remains giving Val Kilmer’s sly Doc Holliday plenty of saucy one liners to balance Kurt Russell’s conflicted Earp. Put Sam Elliot on a dusty street with a gun and a Stetson, good things will happen. The film takes liberties with history (Holliday was…

View original 381 more words

July 16, 2014

Flight to Mars falls far short of goal

On Monday morning June 5, 1939, 22-year-old Cheston Lee Eshleman climbed into the cockpit of a small plane in Camden, N. J. and flew it east. His goal wasn’t to cross the Atlantic Ocean. No, the Gettysburg High School graduate had a much further destination in mind.

On Monday morning June 5, 1939, 22-year-old Cheston Lee Eshleman climbed into the cockpit of a small plane in Camden, N. J. and flew it east. His goal wasn’t to cross the Atlantic Ocean. No, the Gettysburg High School graduate had a much further destination in mind.

He was going to fly to Mars.

He had given a letter to a “jittery citizen” at the airport asking that it be mailed to the Philadelphia newspapers. The letter noted his interstellar destination and said that Eshleman wanted to return the “visit to Mars on Sunday evening, October 1938 (the night of the Orson Welles radio broadcast),” according to the Ironwood (Mich.) Daily Globe, one of the many newspapers nationwide that carried the story. Orson Welles’ adaptation of War of the Worlds during a radio program on Halloween night 1938 had sent many people into a panic who missed the introduction to show and believed it was a real news program about an alien invasion.

Another reason for his trip was “To survey a temporary hideout for the harmless people so they may escape in time of war the slave-enforced ultra-tragedy when the maniacs versus the he-man feud to destroy themselves and their possessions,” the Daily Globe reported.

Eshleman was born in McKnightstown on January 23, 1917. His parents, Samuel and Bertha Eshleman, owned the Fox Hill Orchards.

However, out on his own, Eshleman had dreams beyond agriculture. Those dreams took a turn for the worse, though, when the airplane that he had rented for $11 an hour developed problems over the Atlantic Ocean. A gas line broke in the aircraft and kept reserve gasoline from being pumped into the main fuel tank.

“This kid just went frantic with fear when he lost the radio beam out of Newark,” Edward Walz, the owner of the airplane, told reporters. “He didn’t know which way to go out there over the water. So he came down the first chance he got.”

The plane crashed into the water about 200 miles east of Boston. Eshleman escaped but the plane sank. Eshleman was left floating in the water until fishermen pulled him aboard their fishing trawler. He had spent 13 hours in the water.

Once ashore, Eshleman was arrested for larceny of the airplane and jailed in the little township jail in Pennsauken, N.J. where he was the sole prisoner.

When arraigned, the blue-eye, brown-haired Eshleman told court reporter George E. Yost that he had planned for a 15-hour flight.

“Where?” Yost asked him.

“Mars,” Eshleman replied with a smile. Then he added, “But there has been one serious misstatement. I’m not a thief. What I planned to do was to pay the $11-an-hour rent for the plane out of my earnings after the trip.”

He apparently figured that a trip to Mar and back would bring him fame and fortune, and it certainly would have if it could have been done.

The police doubted that Mars was Eshleman’s actual destination. They argued that the maps and letters they found in Eshleman’s room at the YMCA said it was more likely that the young man was hoping to reach an airfield in Scotland.

Eshleman was held on $5,000 bail. His parents managed to post a bond and a settlement was worked out with the Walz Flying School. In August, Eshleman’s hearing was postponed indefinitely after his family agreed to pay for the lost airplane.

One might think that after this experience, Eshleman would have been committed to mental institution and would have never flown in an airplane again.

One would be quite wrong. More on that to come.

June 11, 2014

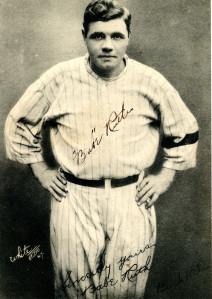

The Return of the King: The Babe Visits the Place He was Discovered

Word had gotten around that Babe was back, the home run king of the American League had returned. Those who heard came to see him; some even took the trolley from Frederick to Thurmont and then switched to the Emmitsburg Railroad to make the rest of the journey to Emmitsburg. So when George Herman Ruth walked onto Echo Field at Mount St. Mary’s College on May 7, 1921, a crowd was there to greet him.

Word had gotten around that Babe was back, the home run king of the American League had returned. Those who heard came to see him; some even took the trolley from Frederick to Thurmont and then switched to the Emmitsburg Railroad to make the rest of the journey to Emmitsburg. So when George Herman Ruth walked onto Echo Field at Mount St. Mary’s College on May 7, 1921, a crowd was there to greet him.

The Babe Discovered

It was far larger than the one that had greeted him when he made his first appearance on the field in 1913.

At that time, Ruth was a young man of 18 years who was playing baseball with the team from St. Mary’s Industrial School for Boys of Baltimore. The school was a reformatory and orphanage. Ruth had been there since he was seven years old because his parents couldn’t care for him.

Brother Matthias Boutlier, the Head of Discipline at St. Mary’s Industrial School, introduced Ruth to the game of baseball, which he quickly took to. The team made the trip to Mount St. Mary’s in 1913 to play a commencement day game against the Mount St. Mary’s freshman baseball team as an opener to the alumni game that featured college alumni playing against the varsity team.

The odds looked good for the alumni to win in 1913. They had Joe Engel, a pitcher for the Washington Senators, on the mound for them. He was able to play in the game since Sunday baseball wasn’t allowed in Washington D.C. at the time and so he was off work.

Engel had once been something special in his own right. When he had attended the Mount, he had lettered in track, baseball, basketball and football. He also pitched a perfect game while on the Mount baseball team. He pitched in the Major League from 1912 until 1920. Once he was sent to the Minor League, Engel would show himself to be an excellent scout. He eventually became known as one of the greatest scouts and baseball promoter in the history of the game.

It could be argued that that talent first began to show itself in Engel in 1913. He was among the crowd who watched Ruth, who stood 6 foot 2 inches tall and weighed 170 pounds, strike out 18 of the 20 batters he faced.

“The St. Mary’s pitcher caught Engel’s eye, partly because of his fastball and partly because of his haircut. Ruth—he was the pitcher, of course—no longer wore his hair cropped short but instead was wearing it in the most mature hair style, that he, Engel, had ever seen on a school kid,” Henry Thomas wrote in Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train. The haircut apparently was tightly clipped on the sides and “roached” or waved over his forehead. According to Thomas it was “in the mode highly favored by bartenders and other cool cats of the day.”

Engel said later of his first impression of Ruth, “He really could wheel that ball in there, and remember, I was used to seeing Walter Johnson throw. This kid was a great natural pitcher. He had everything.”

Then once the game had ended, Ruth cleaned himself up and joined the band to play the bass drum.

That evening on a train to Baltimore, Engel ran into Jack Dunn, the owner and manager of the Baltimore Orioles, which was a Minor League team that had no connection to the current Major League team with the same name. Engel knew Dunn professionally and the two began to talk during the ride. When Dunn heard that Engel had been playing in his alma mater’s alumni game, he asked if anyone on the college’s team showed promise. Engel began talking about the young pitcher he had seen who could also play the drums.

“He’s got real stuff,” Engel told Dunn.

It was the first time Ruth’s name was mentioned professionally, according to Tom Meany a writer who has written extensively about Babe Ruth.

Dunn made a note of the name, but he didn’t immediately act on it. That came later when another person with a keen eye for baseball praised Ruth’s ability.

“Then Dunn heard the same name from Brother Gilbert when he went to scout a possible pitcher at St. Joseph’s. Brother Gilbert, wanting to keep his own player in school and pitching for St. Joseph’s, began to extol the natural talent of a kid named Ruth over at St. Mary’s. Dunn decided it was time to see for himself,” wrote Wilborn Hampton in Babe Ruth: A Twentieth-Century Life.

Dunn went to St. Mary’s Industrial School and watched Ruth pitch during a workout for half an hour and signed him to a contract for $250 a month on February 14, 1914.

By July, Ruth had made the jump to the Boston Red Sox to play in the Major League. He got his first victory pitching during his major league debut on July 11. He was sent back to the Minor League for awhile and returned as a starter the following year. That season his record was 18-8 and his batting average was .315. The Red Sox won that year’s World Series and though Ruth played in it, he grounded out during his only time at bat.

By 1918, the Red Sox began to recognize Ruth’s ability as a hitter. They began using him less as a pitcher and more as a hitter. That year, he led the American League in home runs and the following year, he would set his first single-season home run record (29 home runs).

Ruth was sold to the New York Yankees in December 1919. During the 1920 season, Ruth hit 54 home runs with a .376 batting average, again setting records. His .847 slugging average would stand for more than 80 years.

This was the legend that returned to Mount St. Mary’s. Discovered as a teenage pitcher here, he was now returning as the home run king.

The King Returns

It was big news for Frederick County. Although The Frederick Post didn’t routinely report on Emmitsburg news, it included a paragraph in its May 7 edition noting: “’Babe’ Ruth, the home run king of the American League, spent last night at Mt. St. Mary’s College. He passed through Frederick by auto about 8:30 o’clock yesterday evening. He will return to Frederick early this morning making the return trip by automobile. He will pass through Frederick again between 8 and 8:30 o’clock.”

When Ruth had arrived at Mount St. Mary’s College on Friday evening, he visited the faculty and met them. Then visited a study hall to meet with students there and talk with them. It was there that the students convinced him to spend the night and give a demonstration of the talent that had made him a legend the next morning.

The good-natured Ruth relented and word spread quickly that Ruth would be giving a hitting demonstration the next morning. And so, when Ruth stepped onto Echo Field the next morning, a crowd had gathered to see the man who was on his way to becoming a baseball icon.

“Time after time mighty shouts went up as the Terror of Twirlers sent the white pellet first over the tennis courts in right field and then over the bank in left. For nearly an hour, the King of Swat stood up to the plate and golfed the horsehide to all corners of the lot. He slammed them anywhere and everywhere. Slow ones, fast ones, it made no difference to the ‘Bam,’ he hit them all right on the old nose,” The Mountaineer reported.

Mike Gibbons, director of the Babe Ruth Museum, said, “He hit monstrous flies and let people catch them. He also let the pitcher strike him out, which the crowd loved.”

Ruth stopped only because he needed to get on the road to be elsewhere, but he was besieged by fans who wanted a picture with him or signed balls and bats and “one guy presented a tattoo needle to stamp a little remembrance on for keeps,” according to The Mountaineer.

Ruth left Emmitsburg and drove to Washington where he played in a game against the Senators where he hit his eighth home run of the season.

The 1921 baseball season was a good year for Ruth. He hit 59 home runs, batted .378 and had a slugging average of .846 and led the Yankees to their first league championship.

June 5, 2014

How to make a whale disappear

View of Scheveningen Sands with and without the beached whale. Courtesy of Yahoo News.

Maybe they can change the saying, “The elephant in the room” to “The whale on the beach.”

Art conservators discovered a hidden portion of a painting that when revealed changes the whole meaning of the picture. Hendrick van Anthonissen around 1641 painted “View of Scheveningen Sands” around 1641. More than 100 years later the painting was donated to the Fitzwilliam Museum.

The painting at that time showed people gathered in small groups on a beach in The Hague in the Netherlands. It seemed a typical seascape. The problem was it wasn’t the painting that van Anthonissen had created, at least not entirely.

Of course, no one knew that at the time.

It was only when Shan Kuang, a conservation student at the University of Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum, started cleaning the painting recently that the truth was uncovered…literally.

“Kuang was tasked with removing a coat of varnish, which is typically found on oil paintings, but unfortunately yellows over time. When she began cleaning, a figure emerged on the horizon of the ocean next to a shape that looked like a sail. This was “extremely peculiar and unexpected,” Kuang said. But further cleaning with a scalpel and solvent revealed the floating figure was actually standing on top of a whale, and what at first appeared to be a sail was actually the whale’s fin,” Megan Gannon wrote for Live Science.

It was kind of like an 19th Century version of Photoshop.

No one knows when the whale was painted over, but it was most likely done because societal sensitivities of the day didn’t want to view a dying whale.

The painting can be seen in the Fitzwilliam Museum.

May 27, 2014

There was no stopping “Commando” Kelly during WWII

Ralph F. Kelly of Emmitsburg, Md., was a battle-hardened veteran of World War II by the age of 24. It only prepared him for what was to come.

“He was with the first Allied troops which invaded the North African coast last November, and has been fighting steadily since with the exception of a two-week period spent in a hospital recovering from wounds received in initial engagements,” the Gettysburg Times reported in 1943.

In August of 1943, the Allied Forced invaded Sicily. The soldiers met strong resistance from the Italian and German armies as each side battled to control the high ground in the hilly country.

During the fighting, Sgt. Kelly found himself behind a machine gun firing on the enemy. He fired on the enemy time and again, but eventually, he and the other riflemen in his machine gun nest found themselves isolated from the rest of their company as the Axis soldiers slowly pushed forward.

The enemy fire began focusing on the machine gun nest as it was one a diminishing number of close Allied targets.

“Although the machine gun was isolated from the rest of his company and bearing the brunt of an enemy counterattack, Sergeant Kelly refused to leave his position despite the ferocity of the enemy attack and the fact that his ammunition was seriously depleted, Sergeant Kelly continued firing upon the enemy and inflicted serious casualties,” Kelly’s Silver Star citation read.

More importantly, was what Kelly’s actions allowed to happen. One soldier told Associated Press writer Don Whitehead, “The boys had plenty of guts, and what about Kelly? There’s a soldier for you. Ralph refused to leave his machine gun post until all the riflemen were out and he had no support himself.”

For Kelly, it must have seemed like just another workday.

Kelly graduated from Emmitsburg High School in 1935 and took a job in the Taneytown plant of the Blue Ridge Rubber Company.

Kelly was inducted into the army in January 1942, following in the footsteps of his older brother, Luther, who was a veteran of WWI. Kelly trained for six months at Camp Blanding in Florida and Fort Benning in Georgia before being sent overseas to become part of the First Army of the First Division.

He landed in North Africa with the Allied forces in November 1942 and was hit with shrapnel in his right leg. He spent a few weeks in the hospital and returned to duty with a Purple Heart.

During a fight near Gela, Sicily, Kelly saw a wounded soldier lying in the open and in danger of being shot and killed. Kelly rushed from his place of safety to grab the soldier and carry him to safety. This action earned him an Oak Leaf Cluster for his gallantry.

He was wounded again in November 1944 while fighting in Germany and had to spend a couple more weeks in the hospital.

During his time overseas, Kelly saw fighting in Africa, France, Sicily, Belgium and Germany.

Kelly was given a month’s leave in early 1945. When he returned home to Emmitsburg to visit his family, the Gettysburg Times dubbed him “Commando” Kelly.

“Although his honors do not include the Congressional Medal – highest award of any of the armed forces – Sergeant Kelly’s decorations include enough other ribbons to weight down his tunic,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

In his 2 ½ years overseas, Kelly had won:

A Silver Stars for gallantry in action

An Oak Leaf Cluster (in lieu of a second Silver Star)

2 Purple Hearts for wounds received in action

A Bronze Star that is given only to infantrymen

A Combat Infantryman’s Badge

A Silver Rifle and Wreath that can only be won by an infantryman fighting in the field

A Good Conduct Medal

The European Theater of Operations Ribbon with 5 Battle Stars

Following his leave, Kelly returned overseas to finish out the war. The Gettysburg Times noted, “The Army needs experienced men like him to carry on the battles to victory.”

“Commando” Kelly died in 2003 at Taneytown, Md.

May 7, 2014

Facts in Five

Originally posted on Practically Historical:

Originally posted on Practically Historical:

Easily forgotten statistics…

about our fighting men in the Civil War:

Two out of every five soldiers killed in action would be buried as ‘Unknown’

The average soldier was 23 years old, 5’4″ tall, and weighed 143 pounds

One in ten soldiers were wounded in combat

The Union desertion rate was 12% - Confederate was 16%

One in 65 soldiers died in combat

Edged weapons accounted for less than 2% of Civil War casualties

Only one in seven wounded soldiers would survive their injuries

Death by disease and infections doubled the Killed-in-action rate.

No doubt figured, just amputate

May 6, 2014

The C&O Canal during the Civil War

While the Mason-Dixon Line being the dividing line between the North and the South, an argument could be made that the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was the dividing line between the Union and Confederacy. Running alongside the Potomac River as it does, Virginia was directly south of the canal and Maryland was to the north. Whenever you read about an army crossing the Potomac River, it also had to cross the canal.

While the Mason-Dixon Line being the dividing line between the North and the South, an argument could be made that the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal was the dividing line between the Union and Confederacy. Running alongside the Potomac River as it does, Virginia was directly south of the canal and Maryland was to the north. Whenever you read about an army crossing the Potomac River, it also had to cross the canal.

The unlucky location meant that the canal was vulnerable to destruction by both the Union and Confederate armies

“In some instances, battles were fought so close to the canal that the company’s property was hurriedly made into hospitals and morgues,” Elizabeth Kytle wrote in Home on the Canal.

The canal boats were considered military targets and Confederate soldiers made a habit of commandeering them at the start of the war and confiscating their cargo. One of these boats was owned by Cumberlander Thomas McKaig and held at Harpers Ferry until all the salt it was carrying in its holds was removed. Whether this was an act of piracy or not is debatable. Since McKaig was a Southern sympathizer, he might have made arrangements to deliver the salt to the Confederacy rather than the Union.

Early in the war, the Union Army seized the Alexandria Aqueduct and drained in to hinder any plans to canal boats and their cargo into Virginia and the primary cargo that everyone wanted was Allegany County coal.

“A specialized ‘super-coal,’ Maryland’s product was particularly suited for New England textile mills and for steamship bunkering, and it had been used successfully for smelting iron. Thus, with Virginia coal no longer available to the northeastern market, Maryland’s contribution became increasingly important to the Union Cause,” National Park Service Historian Harlan Unrau wrote in The Chesapeake and Ohio Canal During the Civil War: 1861-1865.

Built to Last

The Confederate Army attempted multiple times to destroy the canal during the war or at least damage it so it wouldn’t hold water, thereby stranding the canal boats and keeping the coal from reaching Washington.

Henry Kyd Douglas, a Marylander who served on Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s staff wrote that the general made several trips to dam no. 5 in Washington County with the intent to destroy it “thereby impairing the efficiency of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, over which large supplies of coal and military stores were transported to Washington…”

However, Jackson and other Confederate officers soon found out that this wasn’t as easy as it seemed. In December 1861, Jackson pounded the dam with artillery, but he couldn’t breach it. Other officers had similar experiences when trying to destroy the canal. The masons who built the canal built it to last. Jackson’s men finally resorted to digging a channel to divert water, causing the canal to dry up south of the dam. This left boats sitting in the canal and coal sitting in the warehouses in Cumberland that couldn’t be shipped out.

Most of the damage to the canal was done early in 1861 and repaired before the First Battle of Bull Run except for a except Edwards Ferry, a culvert three miles above Paw Paw Tunnel, and the Oldtown Deep Cut. According to Unrau, “it took an 80-man crew with 20 horses and carts some 25 days to restore navigation at the large breach near the aforementioned culvert and the heavy rock slide at the Oldtown Deep Cut.” While the last repairs were underway, General Robert Patterson dispatched a company of troops to Hancock to protect the waterway from Williamsport to Cumberland.

Problems in Cumberland

The disruption to the canal trade, along with the uncertainty of who controlled the B&O Railroad, sent Cumberland into an economic recession. William Lowdermilk wrote in The History of Cumberland, Maryland, “Her great thoroughfare, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, was interrupted and her Canal closed. Trade from Virginia was withdrawn. Every industry was stopped or curtailed; stores were closed and marked ‘for rent;’ real estate sank rapidly in value. Merchants without customers slept at their counters, or sat at the doors of their places of business. Tradesmen and laborers, out of employment, lounged idly about the streets. The railroad workshops were silent and operations in the mining regions almost entirely ceased. Then commenced a deep, painful feeling of insecurity and an undefined dread of the horrors of war. Panic makers multiplied and infested society, startling rumors were constantly floating about of secret plots and dark conspiracies against the peace of the community and private invidivuals,”

Protecting the Canal

Because of the problemns with raiders disrupting trade on the canal, President Abraham Lincoln had also authorized Representative Francis Thomas, a former president of the canal company in 1839-41, to organize four citizen regiments to protection canal property and boaters on the canal and along boat sides of the Potomac River. The companies would be called the Potomac Home Brigade.

While the lower sections of the canal saw heavy actions taken at times to destroy it, the upper sections saw relatively few problems. There were minor skirmishes and vandalism, but noting along the lines of what was seen on the canal below Williamsport.

It is believed that one of the reason that the upper sections of the canal weren’t subject to the same attacks as the lower sections was that Canal President Alfred Spates had made an agreement with the Confederacy about military targets through an aide to General Robert E. Lee. While the agreement is known to have existed, the terms were never made public, according to Unrau.

Confiscation

The following spring, the ironclad Merrimac had officials in Washington fearing that their city could be bombarded. Desperate for a way to keep the dangerous, new sailing vessel out of the Potomac River, government officials commandeered more than 100 canal boats at Georgetown.

“Some were filled with rocks and taken down to the river so they could be sunk if it became necessary to block the channel. Six or eight of them actually were sunk later; the others were returned to their owners,” Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles wrote in his diary.

Boats were confiscated two other times during the year, but in the other instances not nearly as many boats were commandeered and they weren’t kept from their work as long. When 40 boats were confiscated later in 1862, they were towed to another river to be used as bridges for Union troops to cross the river.

Cumberlander A.C. Greene, one of the canal directors, wrote to the Canal Company complaining that between the military actions against the canal and bad weather, “There has be no real navigation on the canal this year.”He added that the “very existence of the canal” was “trembling in the balance.” It would be impossible for the boatmen to replace in 1862 the 100 boats held by the government.

He wrote the letter in August and the following month, the Battle of Antietam occurred near the canal, shutting it down further. The tolls the Canal Company collected during September and August were less than 9 percent of the amount collected in 1860, which had been far from a banner year.

Oddly enough, as Union fortunes in the war began to turn following this battle so did the outlook for the canal. Business began to pick up the following year and would continue to grow throughout the war.

In Western Maryland, though, Confederate raiders shifted their focus from damaging the canal to destroying the boats. The raiders acted like pirates, capturing the boats, taking what they wanted and burning what was left.

“Rebs are stealing the horses from the Boats clear to Cumbd. Two boats have been robbed within ten miles of Cumbd. and last night a gang of McNeill’s men crossed at Black Oak bottom, passed over Will’s Mountain into the valley of Georges Creek and swept the coal mines of their horses. The American Co. lost sixteen,” Greene wrote to the Canal Company.

When to war ended, the C&O Canal “emerged from the Civil War on both a depressing note and a promising one.” The canal had been abused during the war and left in deplorable condition so much so that it wouldn’t be until 1869 that all of the damage done from the Civil War was repaired. However, trade on the canal had started rising in 1863 and would continue to grow and remain strong through the canal’s golden years of the 1870s.

April 26, 2014

The literal past: a college student’s view of history.

Originally posted on www.seanmunger.com:

Originally posted on www.seanmunger.com:

I’ve been teaching history at the college level for almost 4 years now. I love it and teaching is clearly the job I was born to do, but, like every job, it comes with frustrations. I think almost everybody who pursues a career in education has moments where they despair what their students don’t know when they first walk into the classroom. This article is not that sort of lament. I don’t mind that some of my students don’t know what much about history when I first see them; it is, after all, my job to remedy that situation. What is interesting–and what will be the subject of this article–is how they think about history, and the implications that it might have.

What’s most striking to me about how many of my students think about history is how literally they interpret things. They tend to view actions, processes and eras…

View original 900 more words

April 23, 2014

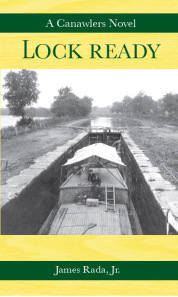

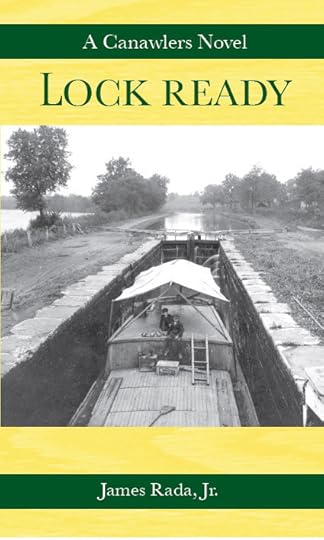

Cover art for “Lock Ready”

Here’s the cover art for my new historical novel that coming out next month. Lock Ready is my first historical novel in seven years. It’s also been 10 years since I wrote my last Canawlers novel.

Here’s the cover art for my new historical novel that coming out next month. Lock Ready is my first historical novel in seven years. It’s also been 10 years since I wrote my last Canawlers novel.

Lock Ready once again return to the Civil War and the Fitzgerald Family. The war has split them up. Although George Fitzgerald has returned from the war, his sister Elizabeth Fitzgerald has chosen to remain in Washington to volunteer as a nurse. The ex-Confederate spy, David Windover, has given up on his dream of being with Alice Fitzgerald and is trying to move on with his life in Cumberland, Md.

Alice and her sons continue to haul coal along the 184.5-mile-long C&O Canal. It is dangerous work, though, during war time because the canal runs along the Potomac River and between the North and South. Having had to endured death and loss already, Alice wonders whether remaining on the canal is worth the cost. She wants her family reunited and safe, but she can’t reconcile her feelings between David and her dead husband.

Her adopted son, Tony, has his own questions that he is trying to answer. He wants to know who he is and if his birth mother ever loved him. As he tries to find out more about his birth mother and father, he stumbles onto a plan by Confederate sympathizers to sabotage the canal and burn dozens of canal boats. He enlists David’s help to try and disrupt the plot before it endangers his new family, but first they will have find out who is behind the plot.

I’ve had fun writing about the Fitzgeralds over the years, but at this point, I see this as my last Canawlers novel. I do have an idea for a non-fiction C&O Canal book, but it will still be years before it comes out. Until then, I hope you enjoy my three Canawlers novels and one novella. The best order to read them in is: Canawlers, Between Rail and River, Lock Ready and The Race.