James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 19

January 14, 2016

Where fairy tales came to life (Part 1)

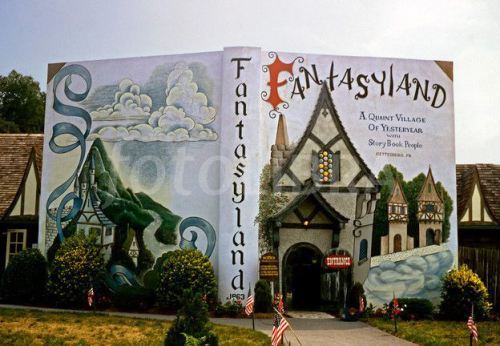

Children entered Fantasyland through a low entrance in a storybook.

It was a place a place where happy family memories were made, and now it only exists as happy family memories. Fantasyland entertained tens of thousands of youngsters and the young at heart from 1959 to 1980.

Kenneth and Thelma Dick had taken their family to the shore for a vacation in 1957. On their way home, they stopped at Storybook Land near Atlantic City, N.J. It was a small park, planned to entertain young children like the three Dick girls.

“My mother kept saying the whole time, ‘I could do better than this. This is so okay, but I could do something so cute,’” Jaqueline White said. She is the middle child of the three Dick girls between her sisters, Stephanie and Cynthia.

White’s parents spent the four hours of the drive home, planning the park and how they would market it. Because they wanted to locate it where there were a lot of people, the Dicks had decide on whether they would build their park in Lancaster or Gettysburg.

Mother Goose greeted children as they entered Fantasyland.

Gettysburg won, in part because Kenneth Dick was from this area and was a graduate of Biglerville High School. However, the Dicks also had a strategic reason for locating the Fantasyland in Gettysburg.

“Parents bring their children to Gettysburg, and they will climb on the cannons and run across the field, but after an hour, they’ll be saying, ‘Dad, what else is there to do?’ Fantasyland gave little kids something to do,” White said.

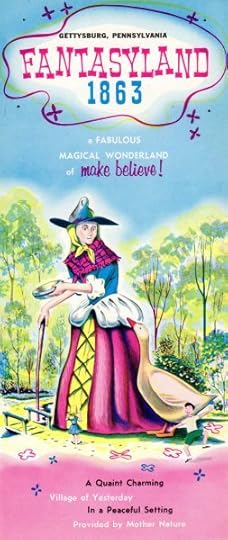

The park opened in July 1959 and was called Fantasyland 1863. “This is Fantasyland…,” the brochure promised. “a world set apart…a world where stories…and dreams…of elves and fairies…and all the storybook characters come to life…in a beautiful setting with the ‘gentle look’ of long ago.”

To enter the park, you had to walk through a short door that part of a large storybook. The door was only five feet tall. If a person walked in without stooping, he or she was charged the children’s price of 60 cents. People who stooped were charged adult admission of a dollar.

“We had a lot of grandmothers get in for the children’s price,” White said. “They loved it.”

The first thing a person saw walking into the park was a 23-foot-tall Mother Goose statue with her goose. A girl in the storybook office could see visitors approaching the statue and speak to them through a microphone, which delighted the younger children. A few keen observers will note that Mother Goose changed her appearance during the park’s life. A fire burned the original statue’s head off and a new one was built to replace it.

Children could also talk to a number of different live costumed characters, such as Raggedy Ann and Andy, Little Bo Beep, the Easter Bunny, or a Fairy Princess.

The cover of the original park map for Fantasyland.

The park was originally 23 acres, but grew over time to 35 acres as new attractions were added. While most of the attractions had a storybook character theme like the Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe or Rapunzel’s Castle, you could also visit Santa’s Village, watch a Wild West Show, take in an animal show where rabbits and chickens had been trained to play baseball, basketball, and the piano. The park featured 11 rides, four live shows, and a number of displays.

“The Winter Wonderland started out as a scary inside ride, but we bought it and my mother transformed it into the Winter Wonderland,” White said.

Thelma had a gift for things like that. She created beautiful gardens throughout the park and designed many of the attractions. On a Christmas trip to New York City, she enjoyed the window displays in Macy’s so much that she walked into the store and bought all of the displays. She then had buildings constructed with each one holding a moving Christmas display. This became Santa’s Village. Musselman’s even paid for apple-oriented attraction to be constructed at the park.

“I liked it best at night,” White said. “We stayed open until 10 p.m. and we had the trees full of colored lights that we turned on. It was beautiful.”

This was all amid a wooded setting with trails that wound through landscaped gardens. You could also see plenty of live animals, such as tame fawns, trained rabbits, calves, and raccoons.

January 7, 2016

A WWII vet remembers D-Day

Donald Lewis stood crammed among a group of friends and fellow soldiers trying not to lose his balance. The landing craft they were on was pushing toward its destination on Omaha Beach at Normandy, France. A strong current threatened to pull them away from their destination.

Donald Lewis stood crammed among a group of friends and fellow soldiers trying not to lose his balance. The landing craft they were on was pushing toward its destination on Omaha Beach at Normandy, France. A strong current threatened to pull them away from their destination.

Lewis was a long way from his hometown of Thurmont, but he along with millions of other young men had been drafted to serve in the armed forces during World War II. Though he had entered the army as a private, he had risen to the rank of staff sergeant.

Lewis stood at the front of the landing craft hanging onto the edge of the wall. Around him, he could hear the explosion of artillery and see the explosions on the water or beach. Things seemed a mass of confusion, but it was all part of the largest seaborne invasion ever undertaken. The coordinated D-Day attack on German forces at Normandy, France. The invasion involved 156,000 Allied troops. Amphibious landings along 50 miles of the Normandy Coast were supported by naval and air assaults.

Lewis’s job in the invasion seemed simple. He was to go ashore first and mark paths across the irrigation ditches that crossed the beach.

However, the landing craft couldn’t make it to the beach. It grounded on a sandbar.

Lewis and the other men were still expected to take the beach, though. The front ramp of the landing craft was lowered and Lewis ran into the water. He suddenly found himself in water over his head, weighed down by a heavy backpack.

“I just had to hold my breath and walk part of the way underwater until my head was above water,” Lewis said.

The Germans started firing on the beach and the landing craft. Lewis focused on his job and began marking the paths where troops could cross.

“When I looked back, men were laying everywhere,” Lewis said. “Just about everyone on the boat was dead.”

After the war, when he was invited back to Normandy for the anniversary of the D-Day invasion, Lewis always turned down the invitations. Now 96 years old, he has never returned to Omaha Beach.

“I’ve seen all I wanted to,” he said.

Though amazingly not wounded during that invasion, he was later wounded in the leg during an artillery barrage. He wound was near his groin and barely missed his groin. Lewis remembers laying in a hospital in England waiting to be taken into surgery.

“A big, ol’ English nurse comes walking up and she pulls back the sheet and looks at the wound,” Lewis said. “Then she said to me, ‘Almost got your pride and joy, didn’t they?’”

Another time, Lewis barely escaped being killed. He and other soldiers were up in trees along a road, waiting to ambush the Germans. However, the Germans were being careful that day.

Another time, Lewis barely escaped being killed. He and other soldiers were up in trees along a road, waiting to ambush the Germans. However, the Germans were being careful that day.

“A sniper must have spotted me up there,” Lewis said. “I knew he hit my helmet. I started down that tree as fast as I could grabbing limbs and dropping.”

When he got to the ground, he took off his helmet and saw that there was a hole through the front of it and a matching one through the back of it. Only the fact that his helmet had been sitting high on his head saved his life.

“People wondered why I didn’t bring the helmet home as a souvenir, but I didn’t want anything to do with it,” Lewis said.

Perhaps his most-pleasant memory from the war was when he was discharged from the army. He was in line with other soldiers being discharged after the end of the war. The soldier at the front of the line would walk up to the officer at the front of the room, receive his discharge papers, salute, and walk away.

“When I got my papers, I let out a war whoop and woke that place up,” Lewis said.

Once back in Thurmont, Lewis went to work on the family farm. He met his wife, Freda, who was a farm girl also from Thurmont and they married in a double ceremony with a couple they were friends with.

Lewis also had a political career. He served two terms as Mayor of Thurmont and one term as a Frederick County Commissioner. He said a group of people tried to talk him into running for governor, but he turned them down, saying, “I’m too honest for that.”

He is now 96 years old and still living on his own. “I want to live to be 100,” he said. “After that, I’ll take what I can get.”

Veterans’ Day is on Nov. 11. Make sure to thank any veterans you know for their service and attend one of the special Veterans’ Day activities going on in the area.

December 31, 2015

The engineering marvel hidden under a mountain

On the day that construction began on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on July 4, 1828, the pressure was on the work crews to get dig the 184.5-mile-long ditch to Cumberland as quickly as possible.

Why the rush? The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad broke ground in Baltimore for its construction began on the same day and Cumberland was the prize for both the canal and railroad.

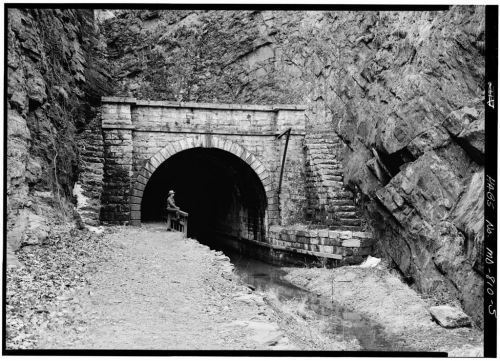

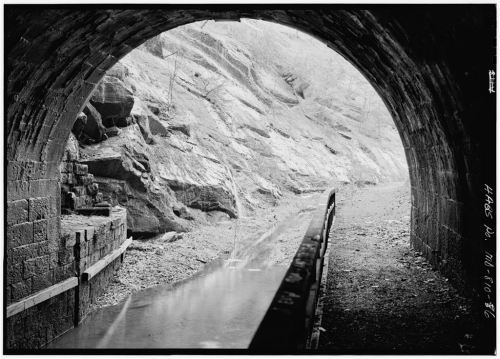

The C&O Canal crews worked hard digging the canal and building 160 culverts, 74 lift locks and 11 aqueducts. However, the canal has only one tunnel—the Paw Paw Tunnel—and it was a major reason why the B&O Railroad beat the C&O Canal to Cumberland by eight years.

Construction

When planning out the route of the C&O Canal, it could have continued to follow the Potomac River through southeastern Allegany County, weaving along the Paw Paw Bends or cut through a mountain. Following the bends in the river would have been the easier course, but cutting a tunnel through the mountain would save five miles and could be done in two years, according to the engineering estimates.

The contractor chosen to dig the tunnel was a former Methodist minister named Lee Montgomery. He began hiring men to work on the tunnel in June 1836. The crews worked from either end of the tunnel digging into the mountain and from above cutting down into the mountain.

Four shafts were dug into the mountain to work from above the mountain. They were set in pairs; one shaft of each pair allowed for debris removal and the other was for ventilation. The northernmost pair of shafts was 122 feet deep and the southernmost pair of shafts was 188 feet deep.

The crews initially blasted away large areas of rock with black powder and then shaped the tunnel with picks and shovels. The rubble was hauled out of the tunnel with horse carts.

“The workers were not experts at blasting, and there was a great deal of overbreakage; the excavation was 40 percent larger than needed,” Elizabeth Kytle wrote in Home on the Canal.

Once excavated, the tunnel arch was formed from layer upon layer of bricks. According to Kytle, the Paw Paw Tunnel lining is 13 layers of brick deep with some places having up to 33 layers. Any open spaces remaining above the arch were backfilled with the excavated material.

“The slaty rock was reasonably hard, but loose enough to make frequent trouble by caving in. It was dangerous work and it went at a snail’s pace,” Kytle wrote.

Montgomery had projected before construction began that his crews would be able to bore out seven to eight feet a day. The reality turned out to be that his crews working three shifts each day only managed 10 to 12 feet a week.

Because of the C&O Canal Company’s financial problems, work was suspended on the tunnel from 1842 to 1847 and construction didn’t restart until November 1848. It was completed by a different contractor, McCulloh and Day, and opened for navigation on October 10, 1850.

The final 3,118-foot-long tunnel is called “the greatest single engineering achievement on the canal,” by the National Park Service. It is 22 feet wide and 24 feet wide and sheathed in more than 11 million bricks.

Operation

Operation

Though the Paw Paw tunnel was an engineering marvel, it was narrow for purposes of the canal. While the canal was designed so that boats could pass each other going in opposite directions, the towpath and canal bed through the Paw Paw Tunnel were both only wide enough for one set of canal mules and one canal boat to move through the tunnel.

Because of the length of the tunnel, a canaller upon reaching one entrance of the tunnel could tell if another boat was already in the tunnel, but it was impossible to tell if the boat was approaching or heading away. The canallers started lighting colored lanterns fore and aft on their boats to distinguish direction. A green lantern was hung fore and a red lantern was hung aft. That way, other canallers could tell whether boats in the tunnel were coming or going.

If the boat was showing a green light, the canal boat captain knew that the boat was approaching and pulled over to wait.

Not that problems still didn’t arise.

Some canal boat captains who were in a rush or just plain cranky, refused to yield the right of way to boats in the tunnel. George Hooper Wolfe tells one of the stories in his book I Drove Mules on the C&O Canal.

Two captains—Jim McAlvey and Cletus Zimmerman—and their boats met in the middle of the tunnel. Neither man wanted to back up, and the captains got into a fist fight over who had the right of way. Then things escalated.

“A gun was drawn and would have been used but for the quick action of a mule driver who knocked the gun from the captain’s hand into the Canal,” Wolfe wrote.

Other boats began entering the canal from both ends of the tunnel and soon the tunnel was filled with boats. As day gave way to evening, crew members of each boat began starting corn cob fires in their cabin stoves to cook meals. Before too long, the tunnel began filling with smoke from the stoves and making staying in the tunnel very uncomfortable.

This sped up negotiation and the captains reached an agreement so that the boats could start moving again.

When traffic on the canal reached its peak during the 1870’s, a watchman was hired to help regulate the traffic at the Paw Paw Tunnel and keep it from becoming a bottleneck. The watchman enforced the Canal Company rules for using the tunnel and could fine canal boat captains $10 for violating them.

The Tunnel Today

After decades of struggling to be successful, the C&O Canal closed for good in 1924. The federal government eventually bought it $2 million, originally planning to turn it into a parkway. However, public sentiment changed the government’s intention and the C&O Canal became a national park instead.

Even today, the Paw Paw Tunnel is still an impressive structure on the C&O Canal and it is still isolated. While there is a parking area just off Route 51 between Paw Paw, W.Va., and Oldtown, visitors still have to walk about half a mile along the towpath to reach the tunnel.

A flashlight is recommended if you want to walk through the tunnel since it is quite dark and there is no interior lighting. It will also allow you to see some of the features of the tunnel, including the weep hole (openings in the brick liner that allow water to pass through), the rope burns on the wooden railing and the brass plates the serve as 100-foot markers inside the tunnel.

Visitors can also hike a steep two-mile long, Tunnel Hill Trail, over the mountain. This trail passes by where the canal builders lived while the tunnel was being built.

December 24, 2015

The Spanish Flu hits Gettysburg (Part 3)

In many municipalities, people covered their faces to try and avoid infection from the flu.

Through November of 1918, the cases, and more importantly deaths, from Spanish Flu decreased. People started breathing a sigh of relief without it going through a surgical mask. Then Adams County then suffered what only a few places around the country saw, a second spike in the flu.

By the end of October, the Gettysburg Times was reporting that 23,000 Pennsylvanians had died from the flu. That represents roughly ¼ of 1 percent of the state’s population that died in one month and the month still had five days left in it when this was reported.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that the flu peaked in Philadelphia during the week of Oct. 16. On that day, not that week, 700 Philadelphians died. Pittsburgh saw its peak three weeks later. So Adams County most likely saw its peak somewhere in between.

The emergency hospital at Xavier Hall in Gettysburg lifted its quarantine at the end of the October and by this point 148 people who had been sent there had died.

Residents were confused about the flu, which only added to their fear of it. The way Spanish Flu struck across the county was inconsistent. The Halloween parade in Gettysburg was cancelled, but the bans on public gatherings were slowly being lifted.

The second wave of Spanish Flu hit particularly hard in the Fairfield area and the eastern part of the county. One doctor was quoted in the Star and Sentinel as saying, “I have just come from four homes. Three or four people were sick in every one of them. One of the families had both parents and the two children ill. I have another family in which there were six cases.”

Reports said the second outbreak wasn’t as pervasive, but it could still be deadly. This is typical of locations where there was a second outbreak.

Adams County moved into the 1918 Christmas season cautiously. Dr. B. F. Royer told the Gettysburg Times, “With the approach of the holiday season too much stress cannot be laid on the necessity of avoiding crowding in the stores, many of which are poorly ventilated.”

Christmas 1918 was somber. A lot of people had lost someone they knew to the flu. Officials urged people to do their shopping early when fewer people would be in the stores. Church Christmas programs were cancelled for fear of having too many people in a confined space.

The Compiler reported that the Stoner Brothers died within 24 hours of each other. They were farmers who had been married for two years and were both in their mid-20s.

The Gettysburg Times reported that Charles Walter who had been sick for two weeks with the flu died on January 2 at home of his parents just before they had to leave for the funeral of their daughter who had died earlier from flu.

The Gettysburg Times reported another unusual case associated with Spanish Flu in 1919. A man named Roy Dice said he had caught the flu, survived and Dr. Swan told him he could start sitting up. Dice began to feel pains in his leg. It quickly swelled up and turned blue. Then gangrene set in and he wound up having his leg amputated.

By January 18, 160 soldiers had died from the flu, most of them at Camp Colt, according to the Star and Sentinel. In Gettysburg, 19 people died and four in Cumberland, Straban, Freedom, Highland townships. This is incorrect simply from counting the obituaries. It may simply be the number of people who were listed as dying specifically from the flu. However, pneumonia deaths at this time were from a complication from contracting the Spanish Flu, and these deaths were roughly equal to those who died from the flu.

Even using the low numbers, Gettysburg’s population was 4,600 at the time. This represents roughly 4 percent of population dying in just a few months.

December 17, 2015

The Spanish Flu Hits Gettysburg (Part 2)

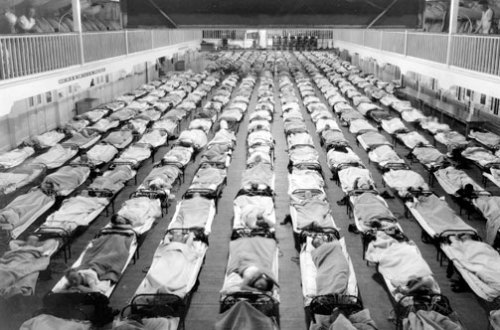

An emergency hospital filled with Spanish Flu patients. This shot was not taken in Gettysburg, but Gettysburg had similar hospitals.

Though it was a different war and a different century, Gettysburg found itself once again occupied by an army. Young men were sent there to learn to fight the Germans in World War I.

They trained to fight the enemy using a piece of state-of-the-art military technology called the tank. The problem was that no one could see the enemy that they were fighting in Gettysburg. It moved indiscriminately through camps and communities injuring and killing men, women, soldier, children. It made no difference.

Before Spanish Flu disappeared, it had killed about 50 million people worldwide or more than four times the population of Pennsylvania.

A factor that played into the spread of the flu and how deadly it was that the U.S. was cramming soldiers into military camps all across the country. The closeness of the quarters helped the flu spread and with more young men contracting the flu than normal, deaths among that age group also increased.

This helped contribute to the W-shaped death curve of the flu. Generally, when flu is fatal, it is with the youngest and oldest in the population, those whose immune systems are weakest. Spanish Flu’s death curve also spiked in the middle with 20-30 year olds, giving it a W shape.

During the first week of the outbreak, no mention was made of the problem in the local newspapers. Yet, the problem was growing. It had already reached epidemic status in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia by Oct. 4.

A headline in The Compiler in early October proclaimed, “The Answer to the Scourge is a Demonstration by Community to Flight It to the Limit. Never has Gettysburg been so stirred as by the scourge of Influenza. Never has the heart of the town been so wrung as by the scourge carrying off the soldier boys who as answered their country’s call in defense of her principles.” This announcement seemingly came out of nowhere since the paper hadn’t been reporting on the buildup to what was a health problem in the county.

Father W.F. Boyle offered Xavier Hall as a hospital. Father Boyle believed that it would be easier to control the flu if you could isolate the sick from the healthy. It was a good idea, but it was too late. Sixty-four cots were set up in the hall as it was transformed into an emergency hospital that quickly filled up.

Prof. Lamond, director of the local Red Cross, sent for nurses to care for the sick. In a show of community spirit, Mrs. Burton Alleman of Littlestown had schoolchildren canvass the town for donations for the hospital. They raised $100 and collected 59 water bottles, 10 fountain syringes, 15 ice caps, 500 sputum cups and 25 serving trays.

Two days after the hospital opened, county schools were closed, which was a common defense against the Spanish Flu. It was also announced that in less than two weeks, 92 soldiers had died at Camp Colt.

By Oct. 12, The Compiler, which had proclaimed that the flu was abating locally just a few days before, now said that it was the “most heartrending epidemic the town has ever been through. … Distress has pervaded the hearts of our people but around this dark cloud is the glow of the wonderful demonstration of our people in town and country and nearby places.”

Warnings were issued and sick families quarantined. Some people even took to wearing surgical masks.

Camp Colt now had 100 dead soldiers. This was one out every six soldiers at the camp and many of the 500 remaining were sick with the flu.

Several of the nurses caring for the soldiers in the emergency hospitals contracted the flu and wound up becoming patients themselves. One of the nurse aides died and even Prof. Lamond caught the flu.

This is one of the insidious ways that the Spanish Flu worked. Many communities were already shorthanded medically because doctors had been drafted to serve in WWI. As the remaining doctors became overwhelmed with their additional workload, many of them caught the flu. The remaining doctors found themselves working longer hours with contagious people. This would wear them down and make them susceptible to flu and the process would repeat.

The dead soldiers were taken to the Grand Army of the Republic Hall in town until arrangements could be made to ship their bodies home. As each body was taken to the train depot, it was given a military escort. This must have been a depressing sight for residents to see 100 times as each soldier was taken to the train that would return him home.

Half of the front page of the newspapers was taken up with obituaries of people who died from the flu.

George Pretz was the author of the lyrics for the Gettysburg College fight song. He was also an army doctor who died in Syracuse. When his wife, Carrie, heard he was sick, she started up to New York, but she didn’t arrive until after he had died. His brother-in-law, Edgar Tawney, “went to Hanover on Monday for flowers and while sitting in an automobile was stricken and being brought home died early Tuesday morning.”

A similar story to this one is that George Stravig, his son, brother and sister all died within a week of each other because of the flu.

By mid-October, all pretense of optimism was gone. A Gettysburg Times headline proclaimed: “Death’s Harvest Still Continues.”

Then a week later, the reports were suddenly upbeat. The Times declared that the flu was all but gone from Camp Colt.

But the Spanish Flu wasn’t done with Adams County yet.

December 10, 2015

The Spanish Flu Hits Gettysburg (Part 1)

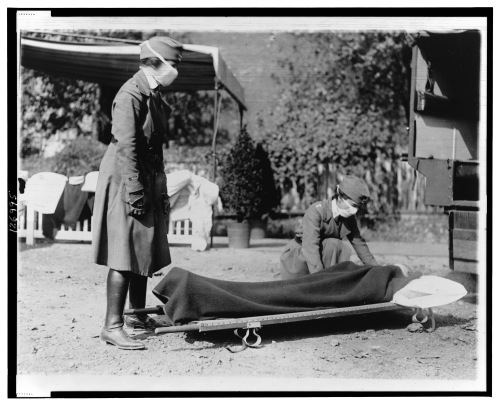

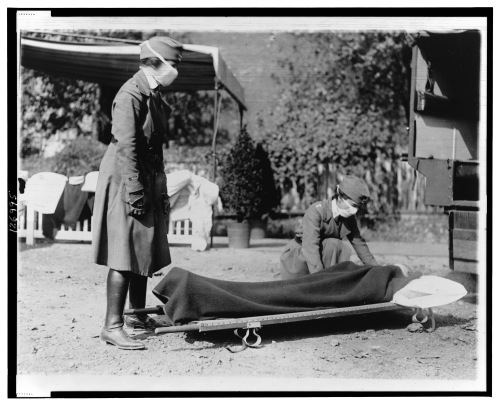

Nurses help a patient suffering from Spanish Flu in 1918.

It seems that every few years the world holds its breath hoping not to catch the flu even if it isn’t spreading among humans. The latest strain of flu has only struck 108 people, but it has killed 22 of them and has spread beyond the borders of China.

Flu is part of life, though, so what do people fear?

They worry that history will repeat itself.

In 1918, the world was at war and about 50 million people would die as a result of it in the fall. It was not World War I that killed all those people. The death toll from the war was 16 million. However, the Spanish Flu was more than three time deadlier in only a fraction of the time.

It was called Spanish Flu because it apparently first appeared in Spain and was that year’s flu strain. When it first appeared in the U.S. in the spring of 1918, it was highly contagious, but it wasn’t any more deadly than a typical flu strain. The problem with the flu virus is that it mutates and some of those mutations can become deadly.

Remember the SARS scare? That killed a few hundred people out of a worldwide population of 6.9 billion.

Now imagine the terror people felt about a flu that killed 2 to 3 people out of every 100 across the world died. If the Spanish Flu struck today, the lethality would be around 185 million.

The Spanish Flu not only killed more people than World War I, but it killed more people in one year than the Black Plague did in 4 years. It was so devastating that human life span was reduced by 10 years in 1918.

Here’s how Gina Kolata described a Spanish Flu attack in her book, Flu, “The sickness preyed on the young and healthy. One day you are fine, strong, and invulnerable. You might be busy at work in your office. Or maybe you are knitting a scarf for the brave troops fighting the war to end all wars. Or maybe you are a soldier reporting for basic training, your first time away from home and family.

“You might notice a dull headache. Your eyes might start to burn. You start to shiver and you will take to your bed, curling up in a ball. But no amount of blankets can keep you warm. You fall into a restless sleep, dreaming the distorted nightmares of delirium as your fever climbs. And when you drift out of sleep, into a sort of semi-consciousness, your muscles will ache and our head will throb and you will somehow know that, step by step, as your body feebly cries out “no,” you are moving steadily toward death.”

Spanish Flu first appeared in Adams County near the end of September 1918. It almost always it made its first appearance in any community during the last week of September, whether it was here or in Europe where there was fighting. This could indicate that that there wasn’t a flash point location so much as this was a strain of flu that mutated. That is a point that is argued, though. Some have tried to set an origin point. Boston and in Kansas are the most-common locations suggested.

The Gettysburg Compiler reported on Sept. 28 that the flu had broken out in Camp Colt, Gettysburg’s army training camp. At this point, they believed that it had come from soldiers who had been exposed to it in Camp Devens in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, which is one of the places where the flu was believed to have started.

To combat Spanish Flu at Camp Colt, 500 soldiers were getting daily throat sprays, which were believed enough to stop the flu. The newspaper reported, “The epidemic seems to be well in hand with treatment before the severe stages.” However, within this first week of breaking out, 125 men had been hospitalized and five had died. These were the men who had come from Camp Devens.

The problem wasn’t well in hand, either. By the time the Spanish Flu was finished with Adams County, so many people had died that it would be nearly 40 years before the county saw a death toll that high again.

The Spanish Flu Hits Adams County (Part 1)

Nurses help a patient suffering from Spanish Flu in 1918.

It seems that every few years the world holds its breath hoping not to catch the flu even if it isn’t spreading among humans. The latest strain of flu has only struck 108 people, but it has killed 22 of them and has spread beyond the borders of China.

Flu is part of life, though, so what do people fear?

They worry that history will repeat itself.

In 1918, the world was at war and about 50 million people would die as a result of it in the fall. It was not World War I that killed all those people. The death toll from the war was 16 million. However, the Spanish Flu was more than three time deadlier in only a fraction of the time.

It was called Spanish Flu because it apparently first appeared in Spain and was that year’s flu strain. When it first appeared in the U.S. in the spring of 1918, it was highly contagious, but it wasn’t any more deadly than a typical flu strain. The problem with the flu virus is that it mutates and some of those mutations can become deadly.

Remember the SARS scare? That killed a few hundred people out of a worldwide population of 6.9 billion.

Now imagine the terror people felt about a flu that killed 2 to 3 people out of every 100 across the world died. If the Spanish Flu struck today, the lethality would be around 185 million.

The Spanish Flu not only killed more people than World War I, but it killed more people in one year than the Black Plague did in 4 years. It was so devastating that human life span was reduced by 10 years in 1918.

Here’s how Gina Kolata described a Spanish Flu attack in her book, Flu, “The sickness preyed on the young and healthy. One day you are fine, strong, and invulnerable. You might be busy at work in your office. Or maybe you are knitting a scarf for the brave troops fighting the war to end all wars. Or maybe you are a soldier reporting for basic training, your first time away from home and family.

“You might notice a dull headache. Your eyes might start to burn. You start to shiver and you will take to your bed, curling up in a ball. But no amount of blankets can keep you warm. You fall into a restless sleep, dreaming the distorted nightmares of delirium as your fever climbs. And when you drift out of sleep, into a sort of semi-consciousness, your muscles will ache and our head will throb and you will somehow know that, step by step, as your body feebly cries out “no,” you are moving steadily toward death.”

Spanish Flu first appeared in Adams County near the end of September 1918. It almost always it made its first appearance in any community during the last week of September, whether it was here or in Europe where there was fighting. This could indicate that that there wasn’t a flash point location so much as this was a strain of flu that mutated. That is a point that is argued, though. Some have tried to set an origin point. Boston and in Kansas are the most-common locations suggested.

The Gettysburg Compiler reported on Sept. 28 that the flu had broken out in Camp Colt, Gettysburg’s army training camp. At this point, they believed that it had come from soldiers who had been exposed to it in Camp Devens in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, which is one of the places where the flu was believed to have started.

To combat Spanish Flu at Camp Colt, 500 soldiers were getting daily throat sprays, which were believed enough to stop the flu. The newspaper reported, “The epidemic seems to be well in hand with treatment before the severe stages.” However, within this first week of breaking out, 125 men had been hospitalized and five had died. These were the men who had come from Camp Devens.

The problem wasn’t well in hand, either. By the time the Spanish Flu was finished with Adams County, so many people had died that it would be nearly 40 years before the county saw a death toll that high again.

December 1, 2015

Author focuses on little-known nuns’ work during Civil War

This is an interview that I did recently for the Hagerstown Herald-Mail. It was put together by Lifestyle Editor Crystal Schelle.

This is an interview that I did recently for the Hagerstown Herald-Mail. It was put together by Lifestyle Editor Crystal Schelle.

Name: James Rada Jr.

Age: 49

City in which you reside: Gettysburg, Pa.

Day job: Freelance writer

Book title: “Battlefield Angels: The Daughters of Charity Work as Civil War Nurses”

Genre: History

Synopsis: The Daughters of Charity were the only trained nurses in the country at the start of the Civil War. Their work on the battlefields, in hospitals, on floating hospitals and in POW camps helped saved thousands of soldiers’ lives.

Publisher: Legacy Publishing

Price: $19.95

Website: www.jamesrada.com

Facebook: www.facebook.com/jamesradajr

Twitter: @jimrada

How did you discover the stories of the nuns at Daughters of Charity in Emmitsburg, Md.?

I was working for a newspaper in Emmitsburg, and I encountered sisters at meetings and other events. When they found out that I was interested in history, some of them told me about the Daughters of Charity’s involvement in the Civil War. Never having heard the story before, I was interested and wanted to know more.

Why did you feel it was important to tell their story?

While the involvement of Catholic sisters is a little-known story, the Daughters of Charity’s story is more obscure. The Daughters of Charity were, by far, the largest group of Catholic sisters involved in the Civil War. However, when you read newspaper accounts or diaries, they are usually called Sisters of Charity or Sisters of Mercy. These were different orders. I wanted to call attention specifically to the Daughters of Charity and separate their work from the work of the other orders.

How did their training differ from that of others, like Clara Barton?

Daughters of Charity first became involved in health care in 1823. At first, their role was administrative, but they soon expanded into nursing. In the years leading up to the war, many of the sisters gained experience in large-scale health crises by nursing the sick during yellow fever and typhoid outbreaks. As they took on the role of nursing more often, one of the sisters even authored a textbook on the subject, which was used as a training manual for other sisters. They were even caring for Confederate soldiers in New Orleans before war broke out. Once hostilities began, they not only had the experience to help with a large number of casualties, but they had trained sisters in most of the states in the war, ready to go and help.

Barton was not working as a nurse when the war began. She joined with one of the many aid societies that formed after war broke out. These societies were groups of volunteers who were trained in how to provide care to soldiers. They were also limited somewhat in where they could go. This drove her to become an independent nurse in order to be able to go to the soldiers who were still on the battlefield.

During your research, what surprised you the most about the Daughters of Charity?

The first thing that caught my attention was that the Daughters of Charity were so trusted by both the Federal and Confederate governments that they were allowed to cross lines in order give care to any soldier who needed it. This ended after the first year of the war, though, when Confederate spies disguised as sisters were caught.

The other thing that really surprised me was that the Daughters of Charity were the only trained nurses in the country at the time of the war. I guess I had always considered nursing as having a much older history. Most nursing was done by family members or, if the patient was in a hospital, by other ambulatory patients. It wasn’t considered a lady-like career.

During a time when disease was the biggest killer of soldiers, how were the sisters able to save so many men?

Their experiences, which were captured in the textbook I mentioned earlier, allowed them to have a lot of practical knowledge. They knew that patients in a well-ventilated area recovered better. They had seen that patients kept in clean clothes and on clean sheets had fewer infections. They didn’t know why at the time, only that it worked, and that was what was important to them. When disease broke out, they were willing to risk exposure themselves in order to treat the symptoms that soldiers suffered. In many cases, that was enough help to allow the soldiers to recover.

What do you believe would have been the outcome of triage medicine if more women like the Daughters of Charity were on the battlefield?

I believe more soldiers’ lives could have been saved. The Daughters of Charity found themselves stretched pretty thin throughout the war. There were always places they were needed. Some sisters worked in hospitals, while others were sent from hot spot to hot spot. After the Battle of Antietam, only two sisters could be sent to help. When Gen. McClellan found this out, he was a bit upset because he had been hoping for many more, but there weren’t any available to send. Now, once the soldiers were taken off the battlefield and sent to a hospital, they were often cared for by Daughters of Charity there. For instance, many of the Antietam casualties were sent to hospitals in Frederick, Md., that were run by the Daughters of Charity.

What do you hope people learn from your book?

I want people to know what these ladies did during the war. Their contributions were just as important as the battles. Without their knowledge and experience, the casualties during the Civil War could have been much greater.

Where can readers purchase your novel?

While any bookstore can order the book from Ingram, I do know that Turn the Page in Boonsboro carries copies on the shelf. The book also can be purchased from online retailers, including Amazon.com and Barnesandnoble.com, or from my website, www.jamesrada.com. If someone wants a signed copy, then either Turn the Page or my website is the place to get one.

November 26, 2015

START YOUR ENGINES!

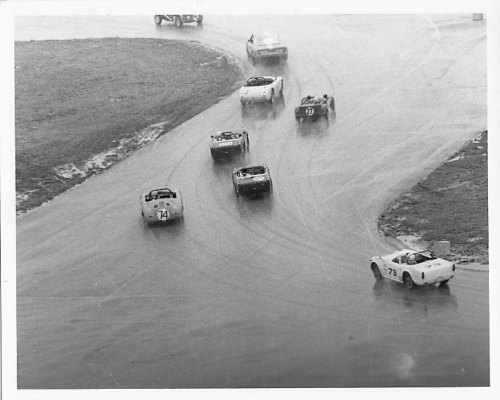

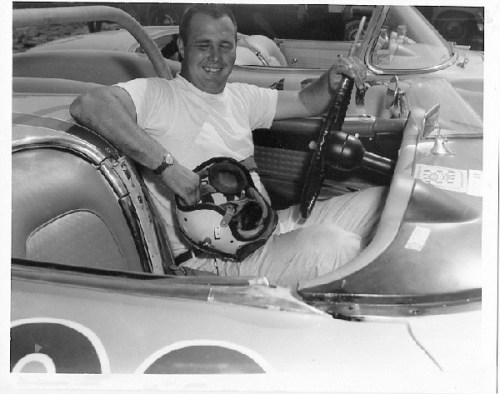

Courtesy of http://www.nationalroadrally.com/index.html.

The Cumberland (Md.) Municipal Airport has never been busier than when sports cars raced around its runways.

Yes, sports cars. Not airplanes.

Each May from 1953 to 1971 racers from across the country would travel to Cumberland to test their sports cars against other top cars to see whose was the fastest. Roger Penske, Shelby Briggs and Carroll Shelby all raced at the Cumberland Airport. The races featured some of the greatest racing cars of the time: Birdcage Maserati, Ferrari Testa Rossa, D Type Jaguar, Porsche 356 Speedster, Cobra, Mustang, Camaro, Sunbeam Alpine, Austin Healy 100, and the Howmet Turbine Car.

“It was a great time,” said Dave Williams. “A who’s who of American sports car racing came through Cumberland.” Williams watched many of those old races as a young man and he remains a racing enthusiast and promoter of sports car racing today.

The Cumberland Municipal Airport offered a 1.6-mile-long course for the racers. In the days before permanent automobile racetracks became common, airport runways offered a satisfactory alternative.

Cumberland Lions Club staged the annual races and their proceeds helped provide free eye exams and glasses for needy children in the county, helped build Lions Manor Nursing Home, contributed to the Wilmer Eye Clinic at Johns Hopkins and provided funding to the local Salvation Army, Boy Scouts of America, and YMCA.

May 1953 saw the first races at the airport. It was a result of months of planning between officials from the airport, Cumberland Lions, and Pittsburgh Steel Cities Region – Sports Car Club of America.

“The initial 1953 event started as Steel Cities/Pittsburgh Regional Races with 80 entries and a rather sparse group of spectators,” Bob Poling and Bill Armstrong wrote in Wings over Cumberland: An Aviation History.

Word spread locally and through the racing community that the airport in Cumberland was a great track on which to race.

The following year 122 racers and their cars showed up to compete before a crowd of around 12,000 people. This led to Cumberland’s regional event becoming a national one.

“Being a national event meant that it was the most-important event in your region in a year,” said Williams.

It also meant that only racers with a national competition license could compete at Cumberland. There were only 1,100 nationally licensed drivers in the country at that time and 284 of them showed up in Cumberland to race in 1955. They came from 40 of the 48 states, Washington, D.C. and Canada. The racers competed in 11 races from 8:30 a.m. until 4:15 p.m. giving racing fans a full days of thrills.

Courtesy of http://www.nationalroadrally.com/index.html.

As a national event, Cumberland began getting featured in media across the country. Sports Illustrated listed the Cumberland Airport Races among the big coming events in the world of sports.

“It represented the largest car race conducted in the US and included many prominent racing figures such as the Briggs Cunningham team of Maseratti race cars. Also, the American manufactured Corvette was making its presence known,” wrote Poling and Armstrong.

The Cumberland Sports Car races continued to grow in popularity with fans. Some of the highlights over the years include:

1956 – Band leaders Paul Whiteman and Skitch Henderson along with actor Steve Allen race in Cumberland.

1957 – Famed racer Carroll Shelby wins the main event at Cumberland.

1958 – Roger Penske taking his SCCA driver’s test in Cumberland in a 283 Corvette. Penske got his license at the cost of his car. He blew the engine and then it fell off the trailer as he took it home.

1965 – The new GT Mustang driven by Bob Johnson wins the Production Car race.

1966 – The Walt Hansgen Memorial Trophy is awarded in memory of a five-time winner at Cumberland. Hansgen was killed in a crash at LeMans earlier in the year.

1967 – What would become a classic—the Z28 Camaro—won its first race.

1968 – Ray Heppenstal drove the turbine-powered Howmet TX Turbo car. Billed as the “car of the future”, it lost its race to Bob Nagel’s McKee Ford 427.

Courtesy of http://www.nationalroadrally.com/index.html.

The peak year for the races, as far as attendance goes was 45,000 people in 1958. This was also the year a racer went over the embankment at the airport. Louis Jeffries was driving a Siata Special when the brakes failed coming off a long straightaway. The car went over the embankment, rolling several times until it reached the bottom. Jeffries was injured but not seriously. It was the only time that this type of accident happened during the races.

“By the early 1960’s, though, airport courses were being replaced by permanent sports tracks and attendance at airport races declined,” said Williams.

Though the community supported the races, some people were starting to complain about the ground at the airport being torn up and that the cars racing at Cumberland were starting to show their age.

Then the Cumberland Mayor and City Council voted to ban car races at the airport after June of 1971. This allowed the 1971 race to go on. Only 200 cars entered the races and competed against each other before 12,000 fans. Almost as if to mark the sadness of the last airport races in Cumberland, it rained through much of the day.

The Federal Aviation Administration agreed with the actions of the city government. In a letter to the city, an FAA official wrote that “it is evident that increased use of the airport requires that all facilities be available for aviation purposes.”

Amateur racing had been struggling in recent years not only because access to airports was being denied organizers, but insurance costs for such events were rising dramatically. Also, many of the big-name draws for these events had turned professional, taking much of the fan base with them.

Allegany County continues to have autocrosses but nothing like the head-to-head competition that once thrilled residents.

For a great selection of historic pictures and information about the Cumberland Road Rally, visit http://www.nationalroadrally.com/index.html.

Courtesy of http://www.nationalroadrally.com/index.html.

November 12, 2015

What one rose buys

Each year, congregations of three churches in Chambersburg, Pa., offer a single rose to a member of the city’s founding family. It is a simple gift, but one that has been given year after year, decade after decade, century after century without fail.

The reason the rose is given each year is simple. The rent must be paid.

Benjamin Chambers founded Chambersburg in 1734 when a representative of the Penn family issued him a “Blunston license” for 400 acres. Because of the area’s Scotch and Irish residents, the Falling Spring Presbyterian Church was the first church established in the town. In 1768, Chambers gave the congregation land for a church and cemetery in 1768 because he recognized the role that religion played in creating a community and giving it a moral core.

In 1780, he offered land to the First Lutheran Church and Zion Reformed Church, which were both working to grow and establish themselves in the town. All that he asked in return for the land was that an annual rent of one single red rose be paid to his family or a descendant.

“One of the stipulations in the deed is that it had to be a rose from the church’s grounds,” said Rev. Jeffrey Diller of the Zion Reformed Church.

The payment of the rose rent at the Zion Reformed Church in Chamberburg, Pa. Photo courtesy of the Zion Reformed Church.

It is not known why Chambers chose such an unusual rent payment, but the red rose does have some biblical connections.

The five petals of a red rose were held as symbolic of the five wounds of Jesus Christ by early Christians. It is also associated with the blood of Christian martyrs or representative of the Virgin Mary. Some legends say that white roses grew in the Garden of Eden, but they turned red with shame when Adam and Eve fell from grace.

One of these may have been Chambers’ reason for choosing the red rose as payment or it may simply have been his favorite flower.

“The son, Capt. Benjamin had roses lining his walk in front of his house which would have been part of the original settlement of the founder. Later, the area became known as Rosedale,” said Ann Hull, executive director of the Franklin County Historical Society.

Diller also noted that it may have simply been fashionable at the time to give churches land that way. He said that he knows of many other churches throughout the region that pay a similar annual rent.

Whatever the reason, his foresight and generosity allowed the churches to establish themselves in the town.

“We make a big thing of it each year with a program that celebrates the historical aspect of the ceremony,” Diller said.

During a different Sunday in June, each church has a special service in which a member of the Chambers family is presented with the rose rent.

The Zion Reformed Church service begins with a fellowship breakfast on the morning of the second Sunday in June. This is followed by a historical presentation to place the event in context, the ceremony to select the rose and the celebration of the presentation of the rose rent.

Franklin County, Pa., has also paid the rose rent since 2007. It was based on a deed that the late John George, a descendant of the founding Chambers family, found in the Franklin County Courthouse. The 1785 deed transferred lots to the county to hold a courthouse and jail in exchange for a rose rent.

Franklin County Commissioner G. Warren Elliot made the first payment of the rent to George’s widow, June, in July 2007 when he gave her a dozen roses.