James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 15

September 15, 2016

Catoctin Furnace and Thurmont lose 17 men in train wreck

Editor’s Note: This is the final article in a series of three articles about the great Ransom train wreck in 1905.

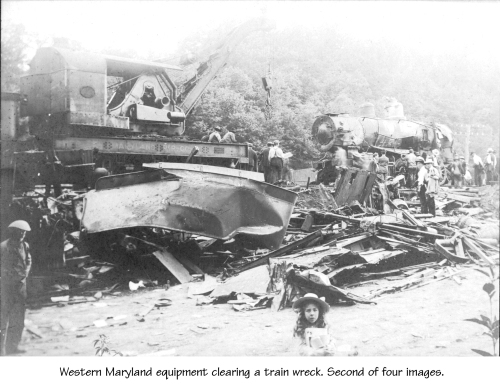

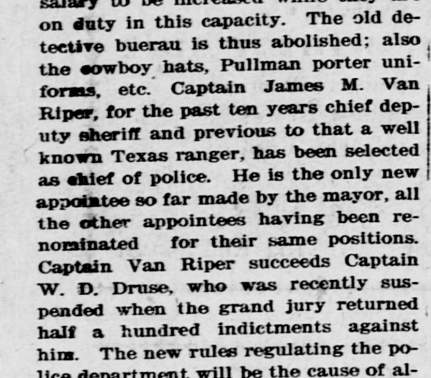

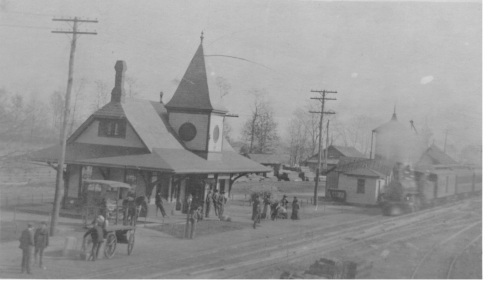

Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

The first report of the deadly Western Maryland Railroad train wreck to reach Thurmont was on Saturday, June 17. It said that 40 to 60 people had been killed. The numbers slowly dropped as more became known and passengers and crew were accounted for. In all, 26 people died and 11 were injured. It was, and remains, the worst accident in the history of the Western Maryland Railway.

“The scenes of agony and distress at the homes of dead victims of the accident cannot be described. They were harrowing in the extreme, and those who witnessed them will never forget the wails of widowed women, orphaned children and relatives of the dead,” the American Sentine reported.

It could have been worse, though. Reports credit the Engineer George Covell of the No. 5 with reducing the casualties, though he didn’t survive himself. He applied the emergency air brakes as soon as he recognized the problem. The track was curving at the collision point so that “the force of the impact was much less upon the coaches than it would have been in a direct line. Railroad men say it is extremely probable that if the collision had occurred on a straight track the coaches would have been telescoped and the passengers subjected to frightful loss of life,” according to the American Sentinel.

The towns affected the most by the wreck were Thurmont and Catoctin Furnace, having 17 of their men killed and seven injured. It also left 13 women widowed and 38 children fatherless according to The New York Times.

“Close family ties and friendships existed among these people. No one was untouched by the tragedy which left a number of widows and fatherless children and dominated thinking in the village for Catoctin Furnace for years,” Elizabeth Anderson wrote in Faith in the Furnace.

With such a large number of the dead coming from a small community, many of the dead were related. McClellan Sweeney was the father of Frank and William Sweeney and brother of Harry. Charles Miller and Charles Kelly were brothers-in-law and E. M. Miller was Charles Miller’s son.

E.M Miller, who escaped injury, helped the reporters identify many of the dead and would not take any payment for the service. When he had finished helping the reporters, he turned to them and said, “My father, Charles T. Miller, and my uncle, Charles Kelly, are both in the wreck and I am sure they are both dead.” He said it with dry eyes, but the newspaper report noted that it was apparent he was “stunned and dazed by the magnitude of the calamity,” American Sentinel reported.

Residents poured out to the local train station in a macabre replay of the townspeople’s regular Wednesday ritual.

“Many of the locals would go to the Thurmont station every Wednesday and take baskets with good things to eat,” George Wireman wrote about the wreck. “They sent them down the line to their family who were working on the railroad.”

On this June night, food was far from their thoughts as residents gathered to await word of whether their sons, fathers and brothers were among the casualties.

Some survivors arrived after midnight, bringing more accurate and horrifying accounts.

On Sunday, June 18, word spread that a train would arrive with the dead at 7 p.m. The train didn’t arrive until about 12:30 a.m. Monday, but the people were still waiting, as was a hearse driven by undertakers Clarence Creager and Elmer Black.

“During that whole of Sunday great throngs of people were at the station waiting for the train that should bring home the silent disfigured forms of those who had gone forth strong and well. It was about 12:30 a.m. when the first shipment of bodies arrived and then came the long procession of hearses and wagons through the town and in the peaceful moon light wended their way to the Catoctin grief stricken homes where the majority of the dead men lived in life,” reported The Catoctin Clarion.

Seventeen funerals were held in Thurmont over the next two days. Out of respect for the town’s loss, all the local businesses in Thurmont closed Monday during the funerals.

Because the dead were all employees of the Western Maryland Rail Road, it quickly became apparent there was no relief plan to help the families with their loss.

“If there had been, these unfortunate men would have under that system, provided for their families in case of death,” a newspaper editorial in The Catoctin Clarion noted.

The Western Maryland Rail Road was running its normal schedule two days after the accident; the same day the dead in Thurmont and Catoctin Furnace were being buried. The accident didn’t tear up any track so the only impediment was the wreckage that needed to be removed. For them, business would go on as usual.

The legal authorities in Carroll County where the wreck happened decided not to hold an inquest about the accident for which they received a lot of criticism, according to the American Sentinel. The State’s Attorney decided that the inquest was not needed because not only was the cause of the accident known but those responsible for the accident had been killed in the collision. Just a week earlier the Carroll County Commissioners had passed an order that the county wouldn’t pay for inquests that weren’t required. “Under the provisions of these articles inquests are only necessary in the cases of persons who die in jail or when the cause of death is unknown and there is a reason to suspect a felony. Neither of these contingencies are applicable to the wreck case and Mr. Steele considers that it would be an unnecessary expenditure of the people’s money to hold an inquest in the case,” the American Sentinel reported.

Even if the state’s attorney had been able to prosecute those responsible for the accident, it wouldn’t have brought back the fathers, brothers, husbands and son who died on the tracks at Ransom.

September 14, 2016

How Research Creates Historical Novels…

Research can be addictive.

… And helps with historical treatment.

I hated history in my youth. But now? I love research. It takes my mind to places that existed long before and can exist again in a historical novel.

The Library of Congress – Historical Newspapers – can take you back to the late 1800’s. I needed 1901 so I found myself in good shape (except I spent hours upon hours finding interesting articles that had nothing to do with my MS, The Last Bordello.) Once I focused, ALL these articles played a pivotal role in my plot line. (I had many more, these are just a few.)

Let’s start with the secondary, still-important, characters and work our way down to Madam Fannie Porter.

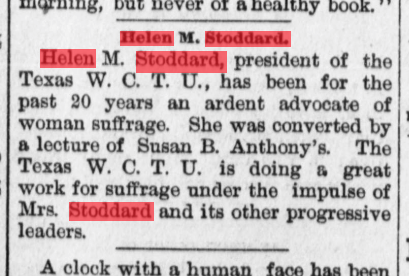

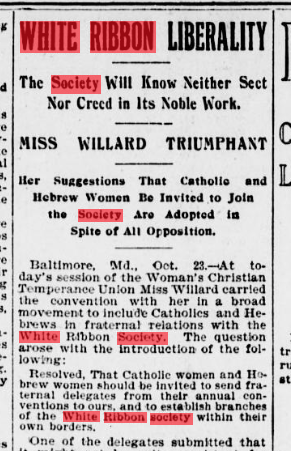

The Women’s Christian Temperance Union :

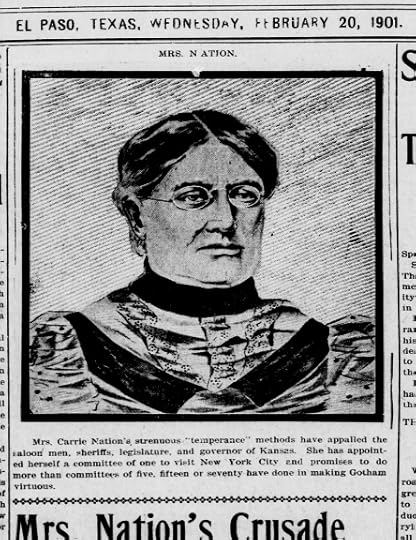

Now, for a sense of place:

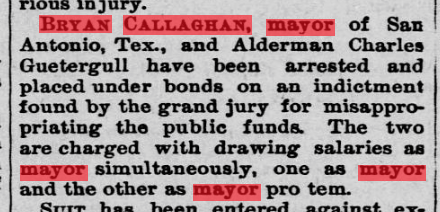

The politicians, Mayor Hicks, former Mayor Bryan Callaghan, Captain James Van Riper:

The “then” never solved murder of Helen…

View original post 56 more words

September 8, 2016

Two trains collide in Ransom

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of three articles about the great Ransom train wreck in 1905.

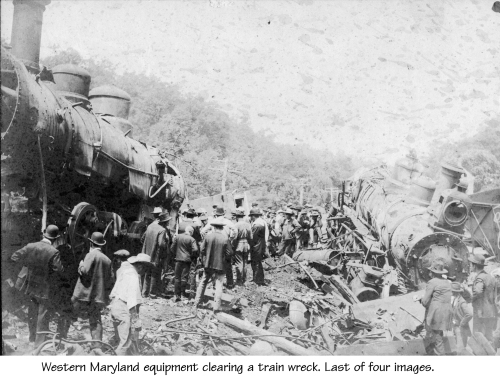

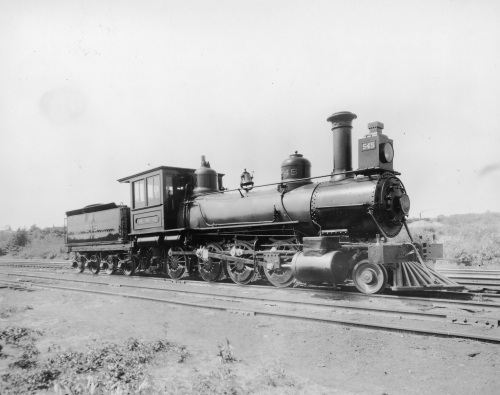

Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

On June 17, 1905, around 5:55 p.m., near Ransom, a little village southeast of Patapsco, Md., in Carroll County, the Blue Mountain Express and a freight train collided head-on.

“Just west of the bridge, they came together with terrific force, the three engines being piled one upon another, fortunately in such a manner that sufficient steam connections were broken, to relieve the boilers, and thus prevent the further horror of one or more explosions,” reported The Washington Post.

“After the freight train whizzed past Patapsco, it was only a couple of minutes and it sounded like the whole train rolled down the track. The noise was terrific! I never heard such an awful noise like that!” said 13-year-old Emil A. Caple who was walking near the tracks on his way to the Patapsco Post Office and General Store.

George C. Buckingham was a conductor on the freight train. He had just looked at his pocket watch and thought the train would be able to make up the five minutes it was running behind. As he put his watch back in his pocket, he felt “the awful plunging jar, crash and grind of wood and steel.”

“There was no time to move. The man ahead of me, a Washington doctor, dived out of his window; we were two seats from the front of the first coach, and I sprang to my feet and amid the groans and shrieks of the injured, I made my way out,” Cunningham told the Hagerstown Daily Mail.

The Frederick Daily News reported that the men who were sitting on the bumper suffered the greatest casualties.

“When the crash came the more fortunate, who were on the engine, jumped or were thrown from the train and were only injured. Those in the baggage car were terribly mangled, and the crews of all three engines were killed. Their bodies all believed to be under the wreckage of the engines,” reported The New York Times.

Flagman George Lynch was at the back of the freight train at the time of the collision. He was the only one of the nine crew members on the three engines to survive.

“There was a jar and then a succession of bumps, but I was not thrown down,” Lynch said.

Despite the impact of the engines in which “the three steam monsters were reduced to scrap iron,” none of the passenger coaches derailed. They all survived because of this, and “none of the passengers were injured aside from slight cuts, bruises and shocks,” according to one newspaper report.

Caple said that everyone who had heard the wreck came running. “I ran right along with them as fast as my legs could carry me. On the way down, we passed a man with a railroad flag in his hand running towards the Patapsco store. Somebody asked him, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘My god, I don’t know.’ He ran up the track to telephone Westminster,” Caple said.

When Caple arrived at Ransom, it was hard for him to see the actual wreck because of all the steam escaping from busted engines and what he did see, he wished he hadn’t.

“People were crawling from the wreck scalded. Some were laying with arms and legs chopped off and screaming and crying were terrible. Carloads of lard in wooden barrels had burst open and many passengers were covered with it and rescue crews had to work in it up to the knees to pull people out. They told all of us to either help or we would have to leave. So no matter what age, every one of us pitched in to help.

“I helped pick up arms and legs. No one knew for sure who they belonged to, so they told us to give them to anybody who didn’t have one that it looked like they belonged to. I helped another man who was scalded. He kept crying that he was so cold, so I got a coat and put over him. They said he had been scalded inside and I believe he died.

“The whole bottom just west of the Patapsco River was strewn with wreckage and bodies and people calling for help.”

Westminster knew of the crash minutes after it happened. Captain H. Clay Eby, a former conductor on one of the trains involved in the crash, lived near the crash site. Though he couldn’t see the collision, he had recognized the sound and what it meant. He had a telephone in his house, so he called E.O. Grimes, the railroad agent in Westminster, and alerted him to the collision.

Once news of the wreck got out, a relief train was put together at Westminster and sent out to help. The injured were taken by train to a hospital in Baltimore. “Just before the first relief train taking the injured to the hospitals of Baltimore left the wreckage began to burn.” Ambulances were also ordered to the scene. An express train following the freight train acted as a relief train for the other side and the passengers on both trains gave all possible aid to the victims.

George Stimmel, a laborer from Thurmont, was one of the passengers taken out of the wreck alive. He was taken to the Hotel Albion in Westminster, but he died the next morning. While on the relief train to Westminster, he “offered a touching and pathetic prayer for his wife and children, pleading earnestly that they might be supported by Almighty God and that the wife might be enabled to train up the children in the paths of christianity and righteousness.”

About 75 men from the Western Maryland and Northern Central railroads used two steam cranes to clear away the wreckage. “With two great steam cranes the three engines were righted and placed upon the tracks, then slowly towed down to the siding near Lawndale. The overturned cars, the broken and twisted axles and machinery were hauled out of the way, and watches, pocketbooks, blank books and other effects belonging to the victims of the wreck were collected,” reported The Catoctin Clarion.

Here are the other parts of the story:

On the road to disaster (part 1)

September 1, 2016

On the road to disaster

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of three articles about the great Ransom train wreck in 1905.

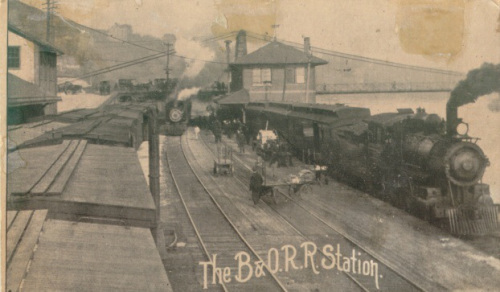

Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

Perhaps the railroaders’ minds were on a tomorrow they would never see. Such thinking might, in part, explain some of their actions on June 17, 1905.

The Western Maryland Rail Road train schedule would change on Sunday, June 18, 1905, but that was tomorrow. On Saturday, June 17, Flagman George Lynch and other members of the freight train crew were waiting with their train on a siding at Gorsuch, Maryland.

Lynch’s eastbound train had pulled onto the siding at 4:25 p.m. to wait for three westbound trains to pass.

“While we were waiting we all got down from the train and sat on a pile of ties near the track. The two engineers and the conductors had their time cards and schedules and we talked for awhile about the time we were making, how long we had to wait for No. 5 and where we would run to after she passed,” Lynch recalled for the Catoctin Clarion.

Drawn by engines 41 and 43, Lynch’s freight train was 18 cars long and heavily laden with coal. Once the three westbound trains had passed, the line would be open for Lynch’s train to continue its eastbound journey to Baltimore, but with only one set of tracks to travel, the other trains had priority.

The crew waited for “considerably” more than an hour. The Union Bridge Accommodation, No. 17, passed on time. Then came the No. 11 Blue Mountain Express, also on time for its first trip of the season.

Lynch retold the events that followed to a newspaper reporter for the Catoctin Clarion.

With a few minutes left before the third westbound train, the No. 5 Thurmont Express, was scheduled to pass, Lynch walked away from the group to get some water at a nearby spring. When he returned, the engineers were in their respective engines. The firemen were shoveling coal into the fires to build up a head of steam.

“Jump on board if you’re going,” one of the engineers called.

Lynch looked at his watch once again. By his reckoning, they still had a few minutes before the train could leave, but he wasn’t going to be left behind. He grabbed a handrail and pulled himself aboard the moving train.

“Where are you fellows going to pass the No. 5?” Lynch called to the fireman.

“At Lawndale,” was the answer he thought he heard over the noise of the steam engine gathering speed.

Lynch couldn’t believe the answer. There wasn’t enough time to get to Lawndale if the No. 5 hadn’t already passed.

“For God’s sake, look at your watch!” Lynch shouted.

The fireman waved his hand at Lynch as if nothing was wrong. Lynch wondered if his watch was simply wrong.

“There were two engineers, the two conductors, and the fireman, five in all, who had the time and knew the schedules as well as I did,” Lynch said.

“Evidently, the engineers or conductors had gotten confused as to how many trains went by,” said local Thurmont historian and train enthusiast George Wireman in a 2005 interview. “But how they could get so mixed up about ordinary work has been a question mark for years.”

One suggestion raised by The Washington Post was, “The fact that a new schedule goes into effect tomorrow may have caused some confusion.” The new schedule had the westbound No. 5 nine minutes slower in reaching Westminster, Md., because a stop in Glyndon, Md., was added. If the crew was thinking that day that the No. 5 was on the new schedule, then they would have thought the train was further east, possibly about 4.5 miles further east than it was. Had this been the case, the freight train would have had time to reach the Lawndale siding.

Another possibility is that since the Blue Mountain Express was making its first run of the season that day, the crew might have been expecting only two trains and not three. However, according to Lynch’s version of events, the crew knew a third train was coming and thought they would have time to pull over.

Lynch said in the Frederick Daily News that he considered pulling down the air brakes, but he deferred to the greater experience of the other crewmen.

The No. 5 had left Hillen Station in Baltimore City, Md., on time at 5 p.m. About 100 passengers were aboard. The train had three passenger coaches and a baggage combination car. Most of the passengers sat in the coaches. It was eating up the route at 30 miles per hour.

The baggage car was filled with railroad workers, many of whom lived in Thurmont, Md. and Catoctin Furnace, Md., two towns next to each other in northern Frederick County. The workers – they were called “floaters” because they traveled to where they were needed to work – had boarded the train at Mount Hope, Md., where they had been working to repair the damage from a small freight wreck there during the week prior. The train was so crowded that some of the men had to sit on the bumpers between the baggage car and the engine tender and between the baggage car and the first passenger car.

It was a choice most of them would not live to regret.

August 25, 2016

Burgess “Cupid” called on to help

It was a bit early for Valentine’s Day, but Gettysburg Burgess William G. Weaver was called on to serve a cupid in January 1950.

It was a bit early for Valentine’s Day, but Gettysburg Burgess William G. Weaver was called on to serve a cupid in January 1950.

He announced at a meeting that he had received a letter addressed to the “Burgermeister” of “Gettysburgh.” The letter was “printed in German script,” according to the Gettysburg Times and was from two women in Hamburg, Germany.

Amelie Schmidt, 48, and Margarethe Lange, 45, wanted to correspond with single men in Adams County. Schmidt wrote that she weighed 170 pounds and Lange wrote that she weighed 155 pounds. Both women said that they were good cooks and housekeepers and they included pictures with the letters. However, since the women only spoke German, any interested male needed to be able to read and write German.

“Through a somewhat sketchy interpretation of it, the burgess deduced that the two women think they would like the United States much better than Germany, and would like to come here,” the Gettysburg Times reported.

Weaver announced a week later that he had gotten his first “nibble” from a man interested in the “friendship circle.” It didn’t come from an Adams County man, though. An unnamed Carlisle man called the burgess asking for the names and addresses of Lange and Schmidt.

“Adams county men may be more cautious, or maybe they haven’t got around to inquiring yet, but the female of the species has not been backward about expressing opinions,” the newspaper reported.

Weaver said that he had also received calls from two women who were outraged that Weaver announced the letter and its contents. Weaver told the newspaper that the gist of the calls was, “We’ve got enough old maids in Adams county now, we don’t need any more.”

The mail-order bride industry can trace its roots in the United States to the American West. The number of men in the West far outnumbered the women so it was difficult for men to find themselves wives.

Asian workers would arrange with a mail-order bride service for brides to come from China or other Asian countries to marry them. It was the business version of arranged marriages.

Successful western farmers and businessmen would write to churches and family in the East or ran advertisements looking for wives. The women would write and send pictures and a courtship would take place via mail until the women agreed to marry a man they had never met in person. They were willing to do this as a way to gain financial security and even explore life on the frontier.

The 1950 incident wasn’t the first time that the Gettysburg burgess had been asked to help arrange marriages. In the lead up to the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg in 1913, a resident of St. James, Mo., wrote to Burgess J. A. Holtzworth in late May. He noted that he and a group of four or five other Missouri veterans were coming to Gettysburg for the reunion. They aged veterans were hoping that the burgess could direct them toward some single women.

The Missourian wrote, “…if you have got a few good widows or old maids who would like to marry and go west, we can accommodate a few. They must be good housekeepers and not too young.”

The Gettysburg Times reported that the burgess would forward the names and contact information of any women who were interested in applying “for the position of unsalaried housekeeper.”

It’s wasn’t reported whether the burgesses had any success in arranging marriages.

Some other Gettysburg stories that you might like:

Farm wife kept secret from Confederate occupiers

Where fairy tales came to life (Part 1)

Small-town high school students prepare for the journey of a lifetime in the middle of the Great Depression (Part 1)

August 18, 2016

Let it snow! Oh, no!

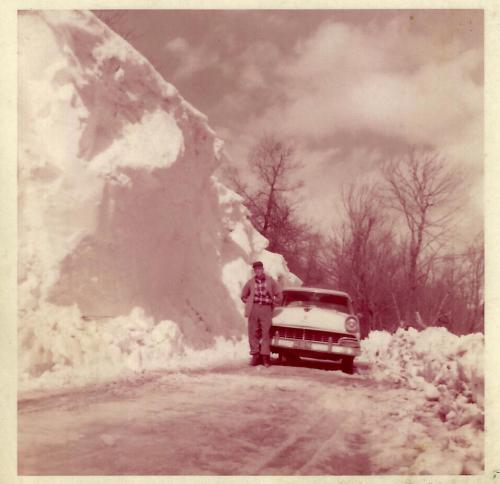

A road cleared of snow during the 1958 blizzard in Garrett County.

The call came in that Thomas J. Johnson needed an ambulance. He was seriously ill and needed to get to the hospital. Normally, it wouldn’t be a problem, but in early 1958, getting anywhere in Garrett County, Maryland, was to say the least difficult.

The ambulance attempted to reach him, but it couldn’t get through to Johnson’s Herrington Manor home. Help came in the form of bulldozers and snow plows that struggled to carve a path through drifting snow as high as 15 feet. It took six hours for the plows to reach the 67-year-old Johnson and rush him to Garrett Memorial.

During another incident that winter, Trooper First Class Robert Henline walked three miles through deep snow that vehicles couldn’t get through to deliver medicine to a desperate family near Gorman.

Other incidents occurred, some serious and some just major inconveniences, but there were a lot of them. In seven weeks in 1958, nearly 112 inches of snow fell on the county, beating out the previously bad winter of 1936. No other winter in the 20th century to that point even came close.

The Cumberland Sunday Times reported that the bad weather “practically isolated most of the county despite heroic efforts of State Roads and county roads crews, National Guardsmen and other volunteers.”

Although the first snows of the new year had fallen mid-January, the first big storm came at the end of the month. Ten inches of snow fell on January 24 followed by three more inches two days later. “For a short time on Friday afternoon there was snow, sleet and ice falling at the same time,” The Republican reported. A heavy fog also slowed things down.

The heavy snows led to the rare occurrence of closing Garrett County schools in the county for three days at the beginning of February.

“It was the first time in several years that there had been the loss of even one day of school,” The Republican noted.

School Superintendent Willard Hawkins said he “was afraid to put the buses on the roads because of poor visibility and icy conditions.” The Republican reported that Hawkins had intended to resume school on the third days until he found out that many children and teachers were still snowbound.

A week later nearly 10 inches of snow fell on three consecutive days. Pleasant Valley, Kempton, North Glade, Sanders Lane, and Herrington Manor were the worst hit, reporting snow drifts of 15 feet or more. With visibility near zero, the Maryland State Police issued an emergency travel only order.

The blizzard left about 40 percent of the county roads impassable for two days, according to Paul DeWitt, assistant county engineer. Garrett County had 140 men working 45 snow plows around the clock to try and open and clear the 740 miles of county roads.

State road crews were running 20 snow plows and a giant snow-blower over the 158 miles of state roads in the county. The only state road that was impassable was Route 495 between Bittinger and Grantsville.

With so much snow on the ground, the snow plows were only able to push it so far off the road before running into previous piles of snow that had been pushed off the road. “By that time there was no place to push it and consequently many of the highways drifted completely over,” The Republican reported.

In Oakland, snow and vehicles competed for space and the snow often won. “Parking space was at a premium and many of those who found places at the edges of the drifts found themselves unable to move when they returned to their cars,” The Republican noted.

All of the snow busted the county’s budget that year with rented equipment costing $1,000 a day and snow removal equipment using 2,000 gallons of gasoline a day.

Although the snow totals blew away previous snowfall records in the county, at least the temperature records still stood. In 1958, the temperature fell to -17 degrees, but the 1912 record was -40 degrees.

You might also be interested in:

Train crashes into county school bus killing seven children

The champion coal miner of the world

Looking Back: Sledding on City Streets

August 11, 2016

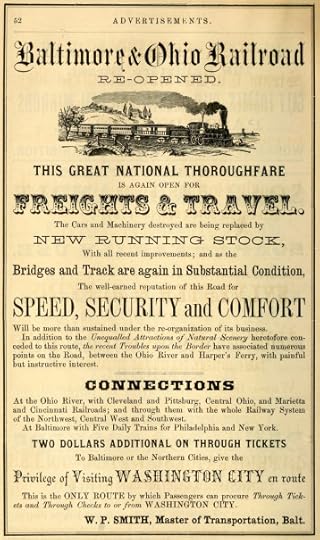

The Engines of War: How the B&O Railroad helped save the Union

From Baltimore’s Pratt Street Riot in April 1861 that saw the first fatality of the Civil War to President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train in 1865, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was a rolling witness to history.

From Baltimore’s Pratt Street Riot in April 1861 that saw the first fatality of the Civil War to President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train in 1865, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was a rolling witness to history.

“You could argue that it was the most crucial railroad in the United States during the war because it ran across the dividing line between the North and South,” says Courtney Wilson, executive director of the B&O Railroad Museum in Baltimore.

At the beginning of the war, the B&O had 513 miles of track that ran from Washington, DC, to Wheeling, Virginia.

“From Wheeling, the train would be taken across the river on floats to Parkersburg,” Wilson notes. From there, connections could be made to other railroads, but the Washington, DC, connection was the critical one. In terms of rail service, the B&O was Washington’s lifeline to the Union.

Despite being in the Union, the rail line ran through states with Southern sympathies or states that were actually in the Confederate States of America. This made it a target too tempting to ignore. Over the course of the war, 143 raids and battles would involve the B&O.

New Tactics

In terms of tactics and strategy, the Civil War was unlike any conflict fought before, largely because of the use of railroads.

Most of the nation’s 200 railroads at the start of the war remained loyal to the Union. Among these railroads, the majority used a uniform distance between their rails. This allowed the Union to move troops and goods faster and with fewer transfers.

This was a significant tactical advantage for the North. The trick was for Union generals to learn to make use of it.

“I would say that they adapted to it very quickly, particularly that they could move troops six times the distance in a 24-hour period,” says Wilson.

“A Southern Railroad”

Marylander John W. Garrett (for whom Garrett County is named) was president of the B&O during the Civil War years. Garrett had been born in Virginia and still loved the Old Dominion, though it was considered an enemy of the state where he lived as an adult.

“His loyalties were in question at first because he had called the B&O a Southern railroad,” Wilson says. He also referred to Confederate leaders as “our Southern friends.”

However, the Confederacy also had doubts about Garrett’s loyalty to the Southern cause. After the Pratt Street Riot, a group of Southern sympathizers threatened to “destroy every bridge and tear up your track” along the railroad.

“It was two to three months before he won the confidence of the president,” Wilson says, and that came about because Garrett, as well as many Maryland businessmen with pro-Southern leanings, realized that their commercial interests lay with the Union.

John Stover wrote in History of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, “John W. Garrett might claim that the B&O was a Southern line, but in his heart he knew that both the prosperity and the future of his railroad lay with the North, the West, and the Union, rather than the South.”

Once Garrett came to this realization, he committed himself to the Union cause and didn’t waver.

Pre-War Engagements

Even before the Civil War started with the bombardment of Fort Sumter in 1861, the B&O had been caught up in the tensions between the North and South.

In 1859, conductor A.J. Phelps sent a panicked telegram to Baltimore that read, in part, “Express train bound east under my charge was stopped this morning at Harpers Ferry by armed abolitionists. They have possession of the bridges and of the arms and armory of the United States.”

This was the beginning of John Brown’s ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry and is often considered the first battle of the Civil War. Brown realized what Confederate generals would also come to see in a few years: If they could sever the B&O Railroad’s connection, they could cripple their enemy.

In 1860, President-Elect Abraham Lincoln made his way from Illinois to Washington, DC, for his inauguration. It was supposed to be a leisurely trip, but rumors began that Lincoln might face violence in pro-Southern Baltimore.

Lincoln’s schedule was adjusted so that his train arrived in Baltimore at 3 a.m. Horses quietly dragged Lincoln’s rail car along Pratt Street from the Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Baltimore depot to the Camden Street depot, where it was transferred to the B&O line. The B&O then delivered the president-elect safely to Washington at 6 a.m.

Damages during the War

In the early years of the war, when Northern Virginia was contested territory, sections of the B&O that ran south of the Potomac River would sometimes be under Confederate control. Whenever this happened, the Confederate Army was sure to burn bridges and tear up tracks.

“Millions and millions and millions of dollars of damage was done to the railroad during the war,” Wilson says.

The B&O’s annual report for 1861 showed that it had been a particularly costly year for the railroad. Losses totaled 26 bridges nearly a mile in length, 102 miles of telegraph line, two water stations, and a lot of rolling stock lost because of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson.

On May 23, 1861, Jackson’s men shut down the B&O between Point of Rocks, 12 miles east of Harpers Ferry, and Cherry Run, 32 miles west of Harpers Ferry. Jackson captured 56 locomotives and more than 300 freight cars. Some of them were put into use with Confederate railroads, while the rest were kept at Martinsburg, Virginia.

The following month, at Martinsburg, Jackson’s men blew up the seven-span railroad bridge; 400 rail cars and 42 engines were destroyed. This represented a significant loss to the railroad and shut down the B&O for close to 10 months.

This turned out to be the Confederacy’s most successful action against the B&O. Though they recognized the importance of the railroad to war-time tactics, they were unable to permanently stop the B&O or match the railroad’s success with the Southern railroads.

Recognizing the importance of the B&O to its own success, the Union government dedicated brigades on the eastern and western ends of the line to protect the B&O from not only regular Confederate Army actions, but also raids from the growing number of ranger units.

Prosperity

The relationship between the B&O and the Union proved beneficial to both. The Union was able to move its men and equipment quickly to where they were most needed.

For instance, when General William Rosecrans required back-up to defeat Confederate General Braxton Bragg in Georgia, help came from 30 trains pulling around 700 cars filled with 25,000 troops. They made a large part of the journey on the B&O.

For the B&O, revenues increased dramatically, and not just from its government contracts to provide transportation.

“Both passenger and freight revenue greatly increased between 1861 and 1865, passenger receipts increased more than fourfold in the four years, and freight revenue climbing nearly threefold,” Stover wrote.

“However, the 1861 revenue, partly because of the destruction caused by Stonewall Jackson, was much below that of previous years.”

Other stories of interest:

Thurmont loses its railroad station

Train crashes into county school bus killing seven children

The final trip of Maryland’s last interurban trolley

August 4, 2016

Thurmont loses its railroad station

The old Western Maryland Railroad station. Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

One of the reasons that there is a Thurmont was lost in 1967.

Thurmont was originally called Mechanicstown, but a movement in 1873 started to come up with a more progressive name for the growing town. Among the supporters of a name change was the Western Maryland Railroad.

“The railroad was all for the idea since it would relieve the shipping and passenger problems caused by a profusion of the ‘sound alike’ communities. There was Mechanicsburg and Mechanicsville, Pennsylvania and several Mechanicsvilles in Maryland as well as our town,” according to A Thurmont Scrapbook.

The Western Maryland Railroad had first reached Mechanicstown on January 9, 1871. The first stationmaster was Harry Shriner.

“Upon the event of the coming of the railroad to Mechanicstown, a group of civic-minded citizens arranged a reception and a banquet for the railroad officials and their guests. It was a big event, taking place in the Stocksdale Warehouse located beside the tracks at the end of Carroll Street,” George Wireman wrote in the Catoctin Enterprise in 1972.

The warehouse served as a temporary depot for the telegrapher and expressman until a permanent depot could be built on the site of the old cannery in Thurmont. The depot had two waiting rooms, an office for the stationmaster and telegrapher and sanitary facilities. The grounds outside were landscaped and there was a water tank at either end of the depot.

By 1890, six passenger, mail and express trains (three eastbound and three westbound) ran through Thurmont daily.

In 1914, Thurmont even had a milk service train running to Baltimore.

During 1923, a young man named S. Elmer Barnhart started working for the Western Maryland Railroad. He was a fresh graduate from the Dodge Institute of Telegraphy and State Agency in Valparaiso, Ind. He had been born in Greencastle, Pa., and served in France with Base Hospital 98 during World War I.

He began his career with the railroad at Edgemont but he soon moved to Rocky Ridge’s station.

“Part of his job involved relaying basketball results by Morse telegraphy from Mt. St. Mary’s College to the Associated Press,” George May wrote in the Frederick Post in 1967.

Barnhart took over operating the Thurmont station in September 1939.

“The peak of his career was in 1952 when he was freight, ticket and baggage agent and operator at Thurmont; agent for the Railway Express Agency; Mayor of Thurmont which included being superintendent of the Municipal Light Company and Chief of Police and an elder and financial secretary of St. John’s Lutheran Church of Thurmont,” May wrote.

As automobiles continued to can gain favor as a form of transportation for Americans, the Western Maryland Railroad stopped passenger service to Thurmont on March 1, 1957. Freight and mail service continued, though.

Occasionally, a few special trains would be scheduled to carry passengers on special excursions, usually to Pen-Mar Park.

“On Saturday, October 12, 1963, the local station resembled a scene from the pages of history when large crowds gathered to ride the special excursions to Pen Mar Park, located a short distance west of Blue Ridge Summit in the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains,” Wireman wrote.

With little notice, the Western Maryland Railroad closed the Thurmont depot on January 13, 1967.

“The need for the station diminished during recent years because of more modern accounting practices in Hagerstown, which took over the work of the Thurmont Agency,” Wireman wrote.

Many people assume that the decision to close the depot came about because Barnhart retired on January 1, 1967, at age 65. He had spent 44 years with the railroad and 27 years in charge of the Thurmont train station.

“On April 4, 1967, the fate of the station was soon learned. A wrecking crew appeared on the scene and began demolishing this Heritage Landmark. Within the short period of three days, a stranger visiting the site would never have realized that a railroad station once stood on this very spot,” Wireman wrote.

While the trains still run through Thurmont, they no longer stop in the town.

Here are some more stories that involve the Western Maryland Railroad in Thurmont:

Bessie Darling’s murder haunts us still

The final trip of Maryland’s last interurban trolley

July 28, 2016

The Fall of the Fly (part 2)

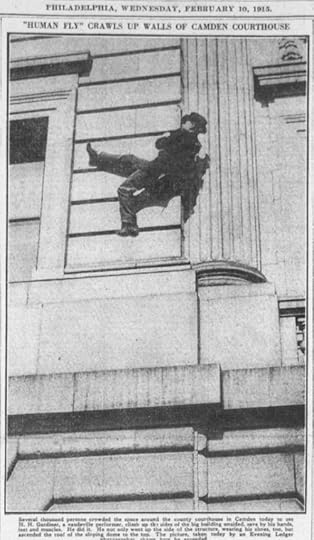

A Human Fly in action.

During the Sunday night performance, thousands of people gathered to watch the Human Fly, George Oakley, repeat his daring deeds. After his first stunt, his assistant, Anna Vivian Murray, urged him to rest a bit before scaling the tall bank building.

Oakley waved off her concerns and told her that he was in a hurry and wanted to leave Chambersburg that evening. It would be at least 9 p.m. by the time that he finished.

“He kissed me and sent me upstairs with the tube,” Murray said later.

Murray went into the building to wait at the second-floor window and Oakley soon began his climb. Minutes later, as he neared the fourth floor and hooked his cane on the inner tube, the crowd heard a “dull snap.” The inner tube had broken and the cane went flying off into the crowd.

“His fall was unbroken except by one man who rushed in in an attempt to save him,” The Repository reported.

Oakley landed on his left side, smashing hard against the pavement. The crowd screamed and several women fainted. The police had trouble getting to Oakley because the crowd was so thick.

Four men lifted Oakley and put him into a cab. Murray, who was said to be his wife, had reached his side by that time. Oakley was conscious. He asked for a priest and how far he had fallen.

“Only three stories. You’re all right. George. You’re more scared than hurt, you’ll be all right,” Murray told him.

This was not Oakley’s first accident in his six years of daredevil climbing. His first accident had actually happened earlier in the year on July 4. Oakley fell 1 ½ stories while climbing a building in Scottsdale, Arizona. He had walked away from the fall with an injured left hand.

However, his climbing partner had been killed in plane stunt a few weeks earlier. He had made a parachute jump and his chute had failed to open.

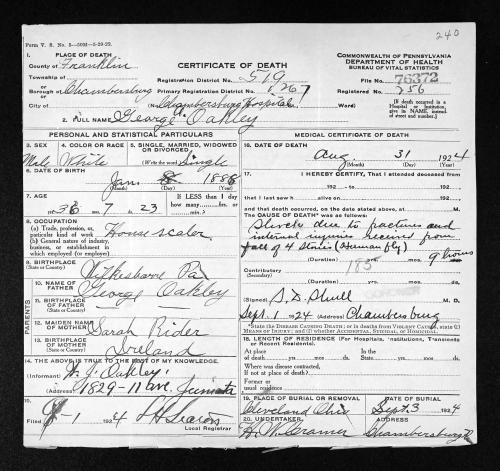

An examination at Chambersburg Hospital showed that Oakley had a number of broken bones including lower vertebrae, his pelvis, ribs, left arm and his breast bone with many of the bones being broken in multiple places. According to The Franklin Repository, his “nervous system suffering much from shock.”

Oakley remained conscious for several hours. Father Noel of Corpus Christ Catholic Church arrived to deliver last rites. Thoughout the night Oakley’s condition grew worse and Murray and a young boy stayed by his bedside.

Oakley died early the next morning. His body was taken to H. W. Cramer’s for preparation for burial.

His wife, Clara, arrived from Cleveland, Ohio, which surprised many people because Oakley had introduced Murray as his wife and the young boy as his son. According to Oakley’s WWI draft registration card, not only was Oakley married, but he had three children.

During the coroner’s inquest, Murray admitted that she and Oakley hadn’t been married, but had been planning to wed.

“I loved Oakley as I thought I could never love any man. We were to be married within a month. I never knew he was a married man, if he really was,” she said.

More importantly, she told the jurors that Chambersburg had been the first time that she had held the inner tube for Oakley’s climb. Chief Byers and Motorcycle Officer Suder tested the tube using the top of an open door at police headquarters to stretch the tube over. Suder said it broke under little strain.

It appeared that a faulty or weak inner tube was the culprit. Coroner Shull ruled that death accidental.

Catch the first part if you missed it:

The Fall of the Fly (part 1)

The Human Fly’s death certificate.

July 21, 2016

The Fall of the Fly (part 1)

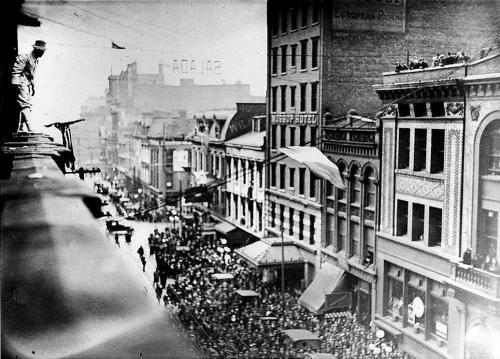

A Human Fly looks over the crowd during a 1916 performance.

Many a young boy loves to climb a tree, pushing the limits of gravity to see how high they can climb and enjoying the rush of adrenaline as the ground grows further and further away. Those boys grow up, though, and realize that if they should fall, they could be seriously injured.

Other boys just never seem to outgrow that urge to climb. They become daredevils. In the early 20th century, these climbers earned the nickname “Human Fly.” They toured the country accepting the challenge to climb the tall buildings in any town. Although many of the famous Human Flys were active in the first couple decades of the 20th century, Human Fly John Ciampa climbed building in the 1940s and early 1950s, Human Fly George Willig climbed the World Trade Center in 1977 and Human Fly Rick Rojatt was a stunt rider in the 1970’s.

In 1924, plans to have an open-air attraction from New York City entertain the crowds during Old Home Week in Chambersburg fell through so Human Fly George Oakley “one of the most daring of present-day human flies,” according to The Franklin Repository, was invited as a replacement act. He was going to be performing in Hagerstown the week before so it fit well with his schedule.

Oakley arrived for two evenings of performances on Saturday and Sunday, August 30 and 31. He did not have the appearance of a daredevil. He was a 36-year-old man of medium height and a stout build.

He performed two daredevil feats for the crowds. For the first stunt, The Franklin Repository, reported, “He will stand on his head on the front bumper rail of an auto, which will attain a speed of 30 miles an hour and suddenly stop. When it stops, Oakley will turn a somersault in the air, and land in the street right side up.”

The second feat was just as, if not more, dangerous. He scaled the outside of the Chambersburg Trust building. “In scaling the walls he used a cane and an automobile inner tube. Someone would precede him to each story inside the building and hold the tube against the outside. The cane he used to hook onto the tube an then he would scale the wall to the window where he would wait for her until she had dropped the tube from the window above,” The Franklin Repository reported.

It was an exciting show that left people holding their breath and shutting their eyes when the tension became too great.