James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 14

November 17, 2016

Confederate Army takes civilian prisoners after the Battle of Gettysburg

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of three posts about the civilians who were taken as prisoners of war by the Confederate Army after the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863.

Libby Prison in Richmond, Va., where the Gettysburg civilian prisoners were kept for a time.

In March of 1865, the country was still at war, but the end was near. The Confederacy was collapsing and the Union was pressing its advantage and forcing the Confederate Army to retreat.

They would not surrender easily, though. Just a couple weeks earlier, 40 McNeill’s Rangers had snuck into Union-occupied Cumberland, Md., and kidnapped General George Crook and General Benjamin Kelley from their hotel rooms. They escaped back into Virginia and delivered the prisoners to the infamous Libby Prison where they were promptly ransomed back to the Union.

The generals’ incarceration hadn’t even lasted a month. They were lucky.

Around the same time negotiations were underway to free the generals, several men returned home to Adams County, Pennsylvania. They had been missing for 20 months. They weren’t victorious soldiers. They were farmers, postmasters, and ordinary citizens. They were also a secret, or perhaps, a shame of the Confederacy because these men were civilians arrested by the Confederate Army at the end of the Battle of Gettysburg and marched back to Virginia when the Confederate Army retreated.

“The hostages were selected from three target groups. They were agents of the government such as postmasters or tax collectors, they defied or criticized the invaders or they were prominent citizens in the community,” James Cole, a descendant of one of the hostages, said in a 1994 interview.

On July 2, 1863, Confederate soldiers arrested Samuel Pitzer and his uncle, George Patterson on the suspicion that they were spies. The rebel sharpshooters were hidden behind the Pitzer Schoolhouse and surprised Pitzer and Patterson.

The two men argued that they were farmers not spies. The soldiers told them that they would have to go to the headquarters for a hearing.

“As they did not find any firearms upon us they assured us that we would not be held after the hearing. When we reached headquarters however Major Fairfax said it was too late to give the hearing that night and put if off till morning,” Pitzer wrote of his experiences years later and reported in the History of the St. James Lutheran Church.

The following day, the Confederates were defeated and started their retreat. All thought of the hearing was forgotten and the prisoners were forced to march south, accompanied by a guard who stood beside each prisoner.

Emanuel Trostle, was another Gettysburg farmer. He lived with his wife and child on Emmittsburg Road. During the battle, a Confederate colonel rode up to his farmhouse and warned him that his family was in danger because of the battle.

“Mr. Trostle, who was crippled at the time, and walked with the aid of a staff and crutch, told the colonel that he could not pass through his pickets. The colonel told him that he would take him through, and accordingly did so,” the Gettysburg Times reported in 1914 when Trostle died.

Trostle had second thoughts the next morning, though. He worried about some of the household goods that he had left behind and headed back, accompanied by a friend. They got as far as the pickets before they were captured.

“He was taken to the battle-field, expecting to be paroled, but the firing opened before the parole could be made out. He was taken to Staunton, Va., walking the entire distance of 175 miles; was on the road six days, and for three days had not a mouthful to eat,” according to the Gettysburg Times.

When the Confederates left Pennsylvania at the end of the Battle of Gettysburg, they left with eight civilians: George Codori, J. Crawford Guinn, Alexander Harper, William Harper, Samuel Pitzer, George Patterson, George Arendt, and Emanuel Trostle.

November 10, 2016

Emmitsburg gets three burgesses in four months

Emmitsburg, Md., once went through three burgesses in four months in 1939.

It began when Burgess Michael J. Thompson died unexpectedly on May 31. He had gone out walking through Emmitsburg, including stopping at the Hotel Slagle, before heading home. He had only been home a few minutes when the heart struck and he died about 12:20 p.m.

“Mr. Thompson had been in ill health for the last two years and the attack this morning was third he has suffered within the last year,” The Frederick Post reported.

He was only 61 years old. He had been born in Waterbury, Conn., in 1877. He loved playing sports, but in 1893 while playing football for Suffield Academy against Taft School, he broke his right leg. He healed, but then broke it again the following spring while sliding into second base during a baseball game.

His playing days were over.

When he attended Holy Cross, he organized the school’s first football team and coached it in 1896 while he was still only a freshman. The following year, he refereed his first game between Boston College and Brown.

He soon became a regular referee for college games.

“His most famous game was the Harvard-Carlisle Indians contest in 1903, when he allowed the ‘hidden-ball’ play. Jimmy Johnson, the Indian quarterback, in a close formation, slipped the ball under the jersey of Dillon, a husky tackle, who lumbered unmolested down the field and across the goal line,” The Frederick Post reported.

He came to Mount St. Mary’s College in 1911 and served as a coach and referee for 23 years before retiring.

He was also a former publisher of the Emmitsburg Chronicle.

Two days before Thompson was buried, John B. Elder became the burgess since he was the head of the town council. Like Thompson, he was also a publisher of the Emmitsburg Chronicle.

With Elder’s move to burgess, Council Member Charles Harner became the head of the town council.

Harner and Elder were the only two members of the town’s governing body at this time. Usually, there was a burgess and three members of the town council. However, the third seat on the council had gone unfilled in the last election. Thompson had been planning on appointing a person to fill the seat, but he had died before it could be done.

On August 21, The Gettysburg Times reported that “Emmitsburg now has its third burgess since the May election as municipal affairs underwent a second unexpected change, occasioned by the sudden resignation last Friday of Guy S. Nunenbaker, retired engineer.”

Elder had unexpectedly resigned from his position as burgess at the beginning of the month. Luckily, Thornton Rogers had been appointed to town council before Elder’s resignation so Harney wasn’t left as the sole member of town government.

Richard Zacharias became the new burgess and served out Thompson’s unexpired term.

This wasn’t the first or last time that Emmitsburg would have trouble finding people to serve in Emmitsburg’s government. Many of its elections lacked contested races and once no one even filed to run for the office of burgess.

“A light vote is anticipated inasmuch as apathy of local citizens to run for office was prevalent during the past week when no one filed his intentions to run for the office of Burgess,” the Emmitsburg Chronicle reported in 1955 just before the election.

The newspaper speculated that most people probably thought that incumbent mayor Thornton Rodgers would run again, but he, too, chose not to seek re-election. When no one had filed for burgess in the election, Rodgers allowed himself to become a write-in candidate.

He was re-elected with 91 votes (out of 438 registered voters) of residents who wrote in his name.

James Edward Houck was elected burgess in 1961, but even then, people referred to the position as mayor. He won the election by only four votes over the incumbent Mayor Clarence Frailey.

Houck wrote in an article for the Greater Emmitsburg Area Historical Society about his time in office, “Being elected Burgess of Emmitsburg in the early 1960’s was quite an eye opening experience for me. The regular duties that you expect to do and the things you want to accomplish are only a small portion of the job.”

Additional charter changers in 1974 made official the change from a burgess to a mayor.

In 2006, the number of commissioners on the board was increased from four members to five. Changes were also made to keep the mayor from voting on issues since he also has veto power.

Other posts that you might enjoy:

The Return of the King: The Babe Visits the Place He was Discovered

There was no stopping “Commando” Kelly during WWII

Thurmont’s “Cat Lady” lived in an old bus

November 4, 2016

Luck keeps Deer Park man alive during WWII

Three Japanese snipers who got into a shoot out with U.S. troops and lost during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The Battle of Leyte Gulf is considered by many to be largest naval battle during World War II, so it is often forgotten that troops were sent ashore to capture Leyte Island once the gulf was won.

The United States’ victory in October 1944 secured the seas around the islands in the Leyte Gulf, but the Japanese still held the islands. On December 7, the 77th Infantry Division, under the command of Major General Andrew Bruce, made an amphibious landing at Albuera, a city on Leyte Island. The 305th, 306th, and 307th Infantry Regiments came ashore without incident, but that peace wouldn’t last.

Kamikaze attacks sunk U.S. destroyers. Japanese troops on the island regrouped and began fighting back against the Americans. Private Denver C. Sharpless of Deer Park, Md., was among the U.S. troops taking fire.

He had been overseas for a year after having gone through basic training at Fort Jackson in South Carolina. He had enlisted in the army at Fort Meade in April 1942 for the “duration of the War or other emergency, plus six months,” which was a standard enlistment for WWII.

The 30-year-old infantryman had just taken cover in a ditch during a firefight when he saw a Japanese soldier emerge from his cover.

“He was the biggest Jap I ever saw,” Sharpless told an interviewer while he was in the hospital recovering from a nerve ailment in his right leg. “Must have been more than six feet and I’m not exaggerating when I say that his head was as big as one of our helmets.”

The average height of Japanese soldiers during the war was under five feet five inches. Sharpless himself was only five feet eight inches tall and weighed 152 pounds.

Sharpless wasn’t too scared of the Japanese solider. Sharpless had found cover and he had his rifle. And that big, hulking soldier made an easy target.

Then the Japanese soldier saw Sharpless and dropped out of sight. The Japanese soldier began crawling and Sharpless saw him again when he passed through an open area 25 yards away.

“Then I began to get frightened because, when I pulled the trigger, my M1 wouldn’t fire,” Sharpless said. “I yanked open the bolt and saw that the firing pin was broken.”

Sharpless was considering scurrying away so he didn’t fall within the soldier’s sights. Then Sharpless saw another American with a Browning Automatic Rifle coming toward him. The American soldier had also seen the Japanese soldier.

Sharpless asked to borrow the man’s rifle, but the soldier told him that he wanted to take out the Japanese soldier. He fired a couple shots and the Japanese soldier went down.

“I wished at the time that I had a camera to take his picture,” Sharpless said. “He looked like one of those oversize freaks you see in comic strips.”

Besides fighting at Leyte, Sharpless also fought on Guam. He earned the Combat Infantry Badge for exemplary conduct under fire and the Philippines Liberation campaign ribbon. Despite surviving enemy fire, the nerve ailment manifested itself a few months later. It severity required that he be sent to a California hospital for treatment.

He was the son of Robert and Bertha Sharpless. His parents had divorced at a young age, though, and he had been raised by his mother in Deer Park. His father was a coal miner who lived in Swanton and had remarried.

Denver died in Ohio in 1991.

October 27, 2016

Consolidating Civil War hospitals in Maryland

When the Indiana Zouaves arrived in Cumberland in June 1861, they attracted a lot of attention from the residents and understandably so. Hundreds of the soldiers arrived at one time wearing brightly colored uniforms.

When the Indiana Zouaves arrived in Cumberland in June 1861, they attracted a lot of attention from the residents and understandably so. Hundreds of the soldiers arrived at one time wearing brightly colored uniforms.

Another group of soldiers began arriving around the same time. These men didn’t march down Baltimore Street in groups to display themselves. They arrived by train and wagon, even canal boat, at all hours of the day and were carried into hotels and warehouse out of public view.

The pageantry of the Civil War had quickly given way to the reality of soldiers who needed treatment. Because of Cumberland’s location at the nexus of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, and National Road, it became an ideal location to concentrate medical services. The wounded could be taken from the battlefronts by wagon and driven to Cumberland or loaded onto rail car that would speed them on their way there.

Once in Cumberland, military doctors, local physicians, Catholic sisters and volunteers took care of their needs.

With soldiers facing a much longer recovery time than they do nowadays, the beds in the dozens of temporary hospitals throughout Cumberland filled quickly. More wounded were coming into the city than were being released from the hospitals or buried in the graveyards. Supplies to treat all of them began dwindling.

In March 1862, the Wheeling Daily Press published a letter from a Cumberland surgeon thanking the U.S. Sanitary Commission in Wheeling for the supplies that had been sent to Cumberland. The surgeon wrote, in part, “We need them badly and they are doing our soldiers much good. We have about 1200 sick. In consequence of our increasing numbers we have not yet a sufficient supply of bed ticks, comfortable pillows, pillow cases, etc.”

Besides needing supplies, Surgeon-in-Charge George Suckley wanted to get the wounded out of the drafty warehouses, engine houses and other buildings that were not intended to house people. He began searching for a location where the wounded could be brought that wasn’t strung out among two dozen locations throughout Cumberland.

The answer came from an unlikely source.

Mary Townsend came from Frostburg one day to visit her husband who was a local doctor helping care for the wounded soldiers. She sat in Dr. Suckley’s office listening to the doctor and her husband discuss the condition of the soldiers as she recounted decades later.

“Can’t you think of some place near here where these convalescent men, who are not improving in this dreadful heat, could be transferred?” Dr. Suckley asked Dr. Townsend.

Mrs. Townsend didn’t even wait for husband to reply. She said that she knew of a place that was 8.5 miles from Cumberland in a “delightful valley I came through this afternoon with the finest spring water, a large tavern, several houses and three large barns not used for years.”

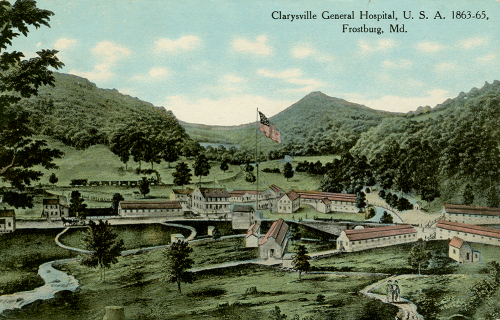

Her description appealed to Dr. Suckley who drove out to Clarysville to see it for himself. “The next day the barns were cleaned and fresh hay put on the floor, then the men were taken up with their blankets and laid on the flood. Many said they had never slept so well, it proved an ideal spot and hundreds of men were saved by the easy transfer,” Mrs. Townsend wrote.

Records show that Dr. Suckley, Dr. Townsend and the assistant quartermaster visited Clarysville on March 4, 1862. They liked what they saw and agreed with Mrs. Townsend that the site would make a fine hospital.

Brigade Surgeon John Carpenter wrote later that hospital buildings were “admirably located at a point sufficiently near for comfortable transportation, and sufficiently distant to enjoy all the advantages of a pure atmosphere. The seclusion of the position is such as to allow the convalescent abundant liberty for suitable exercise in the open air, and its purity produces the most admirable tonic effect upon the enfeebled sick. The supply of water is abundant and its quality excellent.”

Suckley made arrangements with Rebecca Clary, who owned the property, and Mrs. George Clise, who was renting the property, for the U.S. Government to use it. On March 6, 1862, 100 soldiers helped Mrs. Clise move into a nearby vacant house and the transformation of the inn into a hospital began.

The Clarysville Inn had been built in 1805 and became a popular stop along the National Road. However, it was obvious from the start that the two-story brick inn would not offer sufficient space to bring all of the wounded from Cumberland to Clarysville.

Construction soon began on additional facilities. Within a short time, six wards (150 feet long), three wards (130 feet long), a 100-foot-long ward, a 90-foot-long dining room, a70-foot-long kitchen, a 38-foot-long storehouse, a 50-foot-long guard quarters, a 44-foot-long bake house and eight waters closets (10 feet long) were built, according to a report written by Capt. George Harrison, assistant quartermaster in 1865.

“These buildings, though well adapted for use in warm weather, do not afford sufficient protection from the cold of winter for sick and wounded men. the declivity of the ground causes them to stand high, the sides are of rough upright boards with crevices not battened to their full height, and the ridge ventilators having no sash to close, the cold wind and snow penetrate to an extant unbearable by the patients,” Dr. George Oliver, the surgeon in charge following Dr. Suckley, wrote.

Each ward had two rows of iron cots with an aisle down the center, according to Robert Bruce in The National Road.

The influx of wounded continued, though, and even overflowed the capacity of the Clarysville Hospital and filled 15 temporary hospitals in Cumberland and one site in Mount Savage.

The hospital continued serving soldiers until August 1865 when its designation was changed from a General Hospital to Post Hospital. The structure and contents were sold and the government returned the inn to the owners.

The Clarysville Inn remained an operating inn until it burned down on March 10, 1999.

You might also like these posts:

Battlefield Angels: The Daughters of Charity in Missouri During the Civil War

Radio interview about Civil War nursing

The Spanish Flu Hits Gettysburg (Part 1)

October 20, 2016

The circus comes to town in York, Pa.

The big top and midway of the Tom Mix Circus (formerly the Sam Dill Circus). Courtesy of circusesandsideshows.com.

Early Wednesday morning, July 19, 1933, a long train arrived in York, Pa., and stopped near the fairground. The Sam B. Dill Circus had arrived.

“Young America, having caught the infectious circus spirit is likely to be in ahead of both morning orb and circus and be on the lot along with enthusiastic adults to greet the show train on its arrival there,” The York Dispatch reported the day before the train’s arrival.

The unloading and setting up of the circus tents and shows worked smoothly. All of the performers knew their jobs. They had been doing it multiple times each week since the circus had opened its season in Dallas, Tex., on April 9.

Wagons containing the menagerie were rolled down ramps. Trunks were carried off to other areas. Elephants and roustabouts worked to raise the big top as the sun rose. Within a relatively short time, the big top tent was erected and the performers went to work preparing their equipment inside while the roustabouts set up the bleacher seating.

By the time everything was finished around 9 a.m., the cooks in the circus kitchen had breakfast ready.

The Sam B. Dill Circus was scheduled to play two performances, at 2 p.m. and 8 p.m., for York residents.

“Sam B. Dill’s Circus isn’t the biggest circus in the world but what it lacks in size it makes up in quality,” the Amarillo Sunday News and Globe wrote about the circus.

Dill had managed the famous John Robinson Circus, but when it was sold to the American Circus Corp., Dill had struck out on his own. Though not a large circus, Dill’s circus was popular and tended to sell out its performances.

After breakfast, everyone had a short rest and then they began to scurry around getting the menagerie wagons harnessed to horses and in a line. Performers dressed in their bright and flamboyant costumes. At noon, “a long column of red, gold and glitter, with bands playing and banners flying will move sinuously out of the Richland avenue gate,” The York Dispatch reported.

From the Richland Avenue, the parade moved east on Princess Street, then north on George Street to Continental Square. From the square, the circus moved west on Market Street and then back to Richland Avenue. Thousands of spectators lined the route to watch the performers, hear the music, and marvel at the wild animals.

The first wagon was the band wagon where Shirley Pitts, the country’s only female calliope player, conducted the band. Then came the wagons pulling tigers, monkeys, seals, and more. Other flat wagons featured clowns goofing off and Wild West displays.

When the parade arrived back at the fairgrounds, many of the spectators followed them. Although the big top wouldn’t open until one o’clock, they wandered the midway, playing games, getting an up close look at the menagerie, or visiting some of the shows in the smaller tents.

The three-ring show under the big top had dozens of animals such as Oscar the Lion, Buddy the performing sea lion, camels, zebras, horses, elephants, dogs, monkeys and ponies.

Christian Belmont swung on the trapeze, along with aerialist Rene Larue. Mary Miller performed a head-balancing act. The four Bell Brothers showed off their acrobatic skills and Betha Owen owned the high wire. Among the clowns, young Jimmy Thomas was noted as the “youngest clown in the circus world.” He traveled with his mother Lorette Jordan, who was also an aerialist with the show.

The circus also liked to feature a western movie star with its Wild West acts. In 1933, that performer was Buck Steel. The following year, Tom Mix joined the circus. He had been a major western movie star who had seen his popularity decline in the 1920s. In 1935, he bought it from Dill and renamed it the Tom Mix Circus.

Following the second performance at 8 p.m., the performers broke down the circus and loaded it back on the train to head out for the next city by midnight.

You might also enjoy these posts:

Up, up and away in my beautiful balloon!

Burgess “Cupid” called on to help

1933 Chicago World’s Fair

October 13, 2016

Two centuries of Franklin County Masons

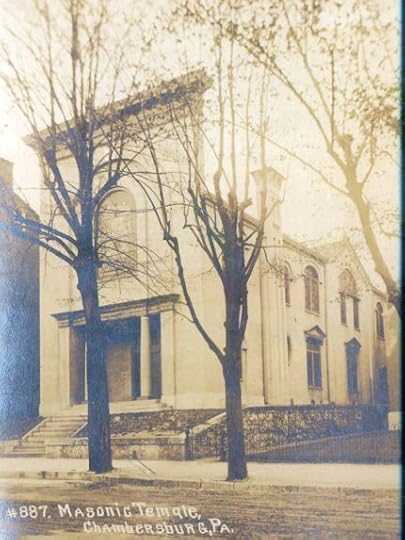

While the George Washington Masonic Lodge in Chambersburg, Pa., wasn’t the first lodge of the Free and Accepted Masons in Franklin County, it is the oldest and April 23, 2016, marks two centuries of service in the county.

Lodge No. 79

The first Masonic Lodge in the county was formed in 1800. General James Chambers, son of Chambersburg’s founder Benjamin Chambers, served as the Warrant Master. Over the next five years, the lodge met 54 times and then closed its doors, not having gotten a strong membership base.

This didn’t end Freemasonry in the county, though. Men continued to travel great distances to meet and fellowship at other lodges. However, the rigors of long travel for a relatively short meeting grows old quickly, and a group of men began petitioning for a new lodge to be formed in Chambersburg.

George Washington Lodge No. 143

George Washington Lodge No. 143

In 1815, the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania acted favorably on the petition and issued a warrant on January 15, 1816, to George Washington Lodge No. 143. The lodge was constituted on April 23, 1816, and the Masons began meeting at various locations around the town.

“The meetings were first held in the Franklin County Courthouse, but that was considered an inconvenience,” Mike Marote, a member of the George Washington Lodge. Another location where the Masons met was Capt. George Coffey’s Inn, but no one is sure where that inn was located in town.

The Masons purchased land for their temple in April 1823 and Silas Harry, a bridge builder, set the work to build the temple for $2,500. The final structure was a two-story brick building that was 32 feet wide by 67 feet long. The foundation stone was laid on June 24, 1823, and the building was occupied on September 16 of the following year.

The 1830s saw a period where Masons were persecuted in the country and the George Washington Lodge decided on December 3, 1830, “to go dark” as Lodge Worshipful Master Kevin Hicks said. The charter was returned to the Grand Lodge in 1831, essentially disbanding the lodge, but the Masons still met quietly and out of the public eye.

During this time, the Masons didn’t own the temple and it was used as a church printing office. The lodge reconstituted itself in 1845, but it wasn’t until 1860 that the George Washington Lodge was able to repurchase the temple for $2,000.

The Burning of Chambersburg

When Confederate General Jubal Early demanded a ransom from Chambersburg in 1864, the people weren’t able to pay it. Early ordered the town burned and $1.7 million in property was lost in the resulting flames.

One area of the town was left untouched, though. The Masonic temple and the buildings in the half block area surrounding it were unscathed.

“Confederate soldiers were posted out front prevented other Confederate soldiers from burning the lodge,” Marote said.

The reason for this is that as the orders were being given to burn Chambersburg, an unnamed Confederate officer saw the lodge and took steps to save it. The surrounding buildings were also preserved because they were so close to the temple that if they had burned, they might have caught the temple on fire.

“Because the temple wasn’t being burned, women and children were able to take shelter inside,” Hicks added.

Since the officer was never identified, the story is considered a well-authenticated legend. Many of the other details have been verified and the half block around the temple was left untouched while the town burned around it.

Teachings

While there is much fellowshipping among the Masons, there is also instruction. Masons learn various speeches, passwords, and signs to move through 33 different degrees. Hicks noted that a man becomes a Master Mason at the third degree, though.

“We are learning what I call moral lessons with allegories,” Hick said.

Though generally believed to be a Christian group, Masons include many faiths. The one requirement is that Masons must believe in a higher being. Each lodge has a book of faith on its central altar. The George Washington Lodge uses a Bible that is more than 100 years old, but other lodges can include a book of faith for the predominant religion of the lodge.

“Freemasonry is not a church,” Hicks said. “I look at it as a steady moral compass. You treat people like you want to be treated.”

Masons are involved in many civic activities and participates in parades and building dedications. They can be identified in full regalia that includes tuxedos, top hats, and aprons.

“We have a belief in working for the greater good and for the good of the community,” Hicks said.

Although the teachings are private matters for Masons, the public has occasionally been invited in to witness these meetings. The last time was in December 2014. It was so well received in the community that not only were all the seats in the meeting room filled, but 37 additional chairs had to be brought in to accommodate the crowd, according to Hicks.

Hicks would also like to open the temple up, on occasion, for artists to come in and use their time in the temple for inspiration for their art. He would then set up the social room as an art gallery where the artists could sell their works one evening.

Other Lodges

Franklin County currently has three other Masonic Lodges: Acacia Lodge No. 586 in Waynesboro, Mount Pisgah Lodge No. 443 in Greencastle, and Orrstown Lodge No. 262 in Orrstown. A fourth lodge, Gen. James Chambers Lodge No. 801, has recently merged with the George Washington Lodge to make both lodges stronger.

The George Washington Lodge boasts a membership of around 800 Masons.

200 Years

To celebrate its bicentennial year, the George Washington Lodge will have a luncheon and rededication of the cornerstone of the original lodge on August 23, 2016. Oddly enough, as of August 2015, the lodge was still unsure as to where the original cornerstone was located. They are hoping to find buried beneath the earth before the ceremony. There will also be an evening banquet at Green Grove Gardens in Greencastle. The Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania will be the featured speaker.

Other posts that you might be interested in:

The mystery of the Masons and their history in Thurmont

Farm wife kept secret from Confederate occupiers

Getting paid what he was worth

October 6, 2016

Edward Woodward: Poet, Gunsmith, Souvenir Maker

One of the unique desk sets made by Edward Woodward. He used artifacts collected from the Gettysburg battlefield.

Edward Woodward was a creative man who came to America from England in the mid-1850s seeking an opportunity to display his creativity. What he found when he and his father arrived in Baltimore was a land of simmering tensions that soon erupted into the Civil War.

On April 19, 1861, a regiment of Massachusetts soldiers was transferring between railroad stations in Baltimore. To do this they had to disembark one train and march through a city filled with Confederate sympathizers to another station where they could board a train to Washington.

The sympathizers attacked the soldiers, blocking the route and throwing bricks and cobblestones at the Union men. The soldiers panicked and fired into the mob, which led to a wild fight involving the soldiers, mob, and Baltimore police. When all was said and done, four soldiers and 12 civilians had been killed. These deaths are considered the first of the Civil War.

Woodward was living in the city at the time, and although it is uncertain whether he saw the melee or heard about it second hand, it affected him.

He was a gunsmith by trade and associates who were Southern sympathizers encouraged him to go South where he would be appointed as the superintendent of a gun manufacturing plant.

His reply was, “I will never go against the flag that waved over me when I crossed the boundless sea to this land of liberty—on it there is no rampant lion to devour nor unicorn to gore. Oh may that flag forever wave until time shall be no more,” according to some of Woodward’s papers still with his family.

At 47 years old, Woodward was not an ideal recruit as a soldier even though he knew his way around a rifle. Instead, he went and joined the Union Relief Association and began caring for sick and wounded soldiers. He went into the hospitals and fed them as he spoke with them.

When the federal government took over Point Lookout, Md., and turned it into a large hospital for Union soldiers and a prisoner-of-war camp for Confederate soldiers in 1862, Woodward volunteered to go and help. However, his time there was cut short when he was severely injured. Though his injury and how he received it is not known, it was severe enough that he had to return home to recover.

Once he recovered, he still wanted to help care for the soldiers. According to family papers, he “volunteered to go to the battlefield of Gettysburg, which he did and remained, until the closing of the hospitals, never making any charge or receiving any pay for his services.” He came to Gettysburg as a member of the Christian and Sanitary Commissions, but when they moved on, he stayed behind to continue helping the sick, but to also start a new life.

He soon resumed his work as a gunsmith in the town. However, he also started a cottage industry in creating souvenirs from the relics of the battle. Woodward created desk sets that contained pieces of artillery shells and weapons. He also made engraved belt buckles from pieces of artillery shells. Some of these items sell for thousands of dollars today.

His obituary in the Star and Sentinel notes, “He was a man of considerable ability, and was known to nearly every student of Pennsylvania College within 25 years.”

Meanwhile, the Homestead Orphanage opened in 1866 to national fanfare. There was much to admire about the operation at first, but then Rosa Carmichael was hired in 1870 as the matron of the orphanage. Things soon began changing and rumors spread that the children in the orphanage were being mistreated.

A story about two of the orphans, Bella Hunter and Lizzie Hutchison was one of the early warning signs. When the two girls tore their dresses, Carmichael made them wear boys’ clothing for two months. This seemed to be the tip of the iceberg as other stories started coming out.

“All sorts of stories were told,” Mark H. Dunkelman wrote in Gettysburg’s Unknown Soldier. “Mrs. Carmichael was said to have suspended children by their arms in barrels. She had hidden mistreated victims from the prying eyes of inspectors. Most scandalous of all were tales of a dungeon in the Homestead cellar, a black hole eight feet long, five feet deep, and only four feet high, unlit and unventilated, where she shackled children to the wall.”

It was also noticed that the orphans were no longer allowed to decorate the soldiers’ graves in Soldier’s National Cemetery on Memorial Day. It all finally became too much for Woodward who had cared for some of those dead soldiers in their last day.

He expressed his anger in a broadside, simply called “Poem” that he then distributed throughout town. The poem criticized her treatment of Bella and Lizzie, calling her “a modern Borgia” and wrote of the orphans, “They are kept like galley slaves, while strangers decorate their father’s graves.”

He wrote two other poems that have survived. One is titled “Woman’s Sin was a Blessing.” It talks about how Eve should be viewed as a good and gentle woman and not simply as the one who brought about the Fall.

The other poem is called “What Did the Soldiers Endure” and deals with Woodward’s wartime work in hospitals. It reads in part:

“They left their homes surrounded with every pleasure

To defend the flag, their country’s greatest treasure,

The native born American, and the volunteer exile,

Marched to the battlefields in rand and file—

“How cheerfully they marched, no fear, wounded they fell,

Devoted to the flag they admired and loved so well.

On the street you see a man with an empty coat sleeve

And another on crutches, oh! how it makes us grieve.”

Edward Woodward died on January, 28, 1894, at the age of 79. Although he had been in ill health for years, the end came quickly. He fell sick on a Wednesday and died on Sunday from “inflammation of the bowels,” according to the Star and Sentinel. He is buried in Evergreen Cemetery.

October 3, 2016

Images of Power, Images of War: Schmucker Art Gallery’s New Exhibit

By Laurel Wilson ’19

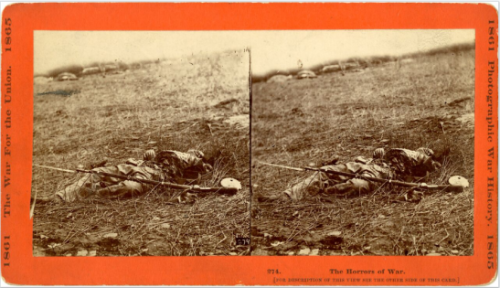

Bodies in Conflict: From Gettysburg to Iraq is a brand new exhibit in Schmucker Art Gallery at Gettysburg College. Curated by Mellon Summer Scholar Laura Bergin ’17, it features eleven depictions of bodies engaged in various conflicts in U.S. history, ranging from the Civil War to the war in Iraq. In addition to curating the physical exhibit found in Schmucker Art Gallery, Bergin also created a virtual version, which can be accessed online through the Schmucker Gallery web page. Of particular interest to those interested in the Civil War are two of the oldest pieces in the collection, a lithograph depicting Pennsylvania Bucktails engaging with “Stonewall” Jackson’s men and stenograph images that depict the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg.

This stereoscope portraying the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg is featured in Bergin’s exhibit. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

This stereoscope portraying the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg is featured in Bergin’s exhibit. Photo via Wikimedia Commons.

Bergin’s self-designed major, Images of Conflict…

View original post 491 more words

September 29, 2016

You’ll shoot your eye out, kid!

The famous line from the movie “A Christmas Story” is “You’ll shoot your eye out, kid.” A variation of that line is said throughout the movie whenever the young boy who is the center of the story expresses his wish for a Red Ryder B-B Gun for Christmas.

The famous line from the movie “A Christmas Story” is “You’ll shoot your eye out, kid.” A variation of that line is said throughout the movie whenever the young boy who is the center of the story expresses his wish for a Red Ryder B-B Gun for Christmas.

However, a bigger threat to young boys’ eyes during the later decades of the 19th Century and even into the 21th Century was not a B-B gun, Red Ryder’s or otherwise. It was the bow gun and its sibling, the sling shot.

Though crossbows have been around for centuries, it wasn’t until 1868 that Howard Tilden patented “The Flying Comet,” a toy bow gun for children. He wrote on his patent application that, “the object of my invention is to provide for children a mechanical toy, that shall be once harmless and amusing.”

Unfortunately, things didn’t work out that way.

Case in point, the Franklin Repository reported in 1890 that, John Zullinger, an 11-year-old boy who lived in Orrstown had injured his right eye playing with a bow gun at his home.

“The little fellow was using a horse shoe nail to shoot at a mark, and while drawing up the bow, the string slipped and the nail struck fairly upon the ball of the eye inflicting a dangerous wound,” the newspaper reported.

John’s father brought him into Chambersburg the next day to have a doctor look at his eyes and see what could be done. The prognosis was not good. It appeared as if the youngster would lose most of his sight in his injured eye.

“This is another warning to boys not to play with dangerous toys. That there have not been some bad accidents in Chambersburg with this ‘cat and dog’ nuisance is almost a marvel,” the newspaper reported.

The newspaper article noted that because bow guns and sling shots had been such a problem in Philadelphia recently that the city police went through each public school in the city and searched the pockets of the boys in the schools. If they found any sling shots or bow guns, the toys were confiscated.

“There have been a number of fatal accidents from them in the city. It wouldn’t be a bad idea to have a similar raid here,” the newspaper suggested.

There’s no reference as to whether such a raid ever took place in Chambersburg, but it is not hard to believe that it wouldn’t have. It wouldn’t be much different than the no-tolerance policy that schools nationwide have for weapons being brought into the school.

As far sling shots and bow guns, they can still cause problems for young boys who test the limits of their toys. Only last year, a 12-year-old Roseville, Minnesota, boy was killed when he was hit in the chest by a rock from an oversized sling shot.

You might also like these posts:

Getting paid what he was worth

What one rose buys

Small-town high school students prepare for the journey of a lifetime in the middle of the Great Depression (Part 1)

September 22, 2016

The music never dies for the Arion Band

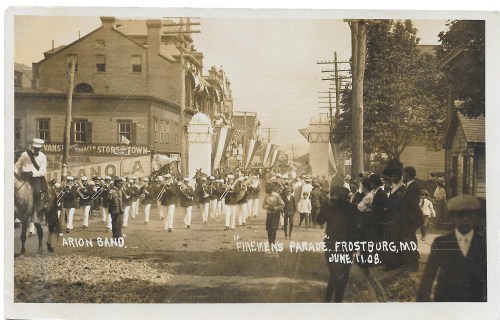

The Arion Band performing in 1908 in Frostburg. Courtesy of the Albert and Angela Feldstein Collection.

For longer than anyone has been alive today, Frostburg, Md., has always had the Arion Band. Before Alexander Graham Bell said, “Mr. Watson, come here I need you,” Watson could listened to the band playing a march or other popular piece of music.

Through the Great Depression and victory at war, the Arion Band brought joy to Western Marylanders and celebrated with them whether it was a holiday or victory at war. Even as music styles changed, the Arion Band kept up with them and adapted.

“The Arion Band is believed to be the oldest, continually operating band in the country,” says Blair Knouse, president of the band. You might find bands that have been around longer, they have gaps in their history where most likely they weren’t performing for a time.

While the Arion Band’s membership fluctuates from season to season, it maintains about 30 active members who love making music, much like the founders of the band. Knouse has played flute with the band for five years.

Back in 1875, German coal miners in the Frostburg area formed a chorus that performed locally. The following year, the chorus purchased instruments so that the singers would have some accompaniment. Local furniture maker Conrad F. Nichol organized the musicians into the German Arion Band and became its first director.

“By 1877, they were saying, ‘This is fun. Let’s forget about singing,’” says band director Ron Horner, who has been in that position since 1995 and is only the seventh director that the band has had.

The band started practicing at the Gross and Nichol Furniture Store on February 5, 1879. This was where they continued to practice until the store burned down in 1888.

“The blaze claimed instruments, uniforms, music, and even the director as Mr. Nichol set about rebuilding his business,” Jay Stevens wrote in his history of the band, which was included in the program for the 125th anniversary performance.

Band members and residents of communities in the area bought new instruments for the band and rehearsals continued in the Odd Fellows Hall in Frostburg.

In 1889, while under the direction of the second band director, John Miller, the band was sworn in at the 4th Battalion Band, a component of the Maryland State Militia. The band nearly went to war during the Spanish-American War.

“The entire band was drafted en masse as an army band, but then the war ended so they wound up not going into the war,” Knouse says.

As anti-German sentiment rose during World War I, the band, under the direction of its third director, George Vogtman, decided to drop “German” from its name.

During the Great Depression and much of World War II, R. Hilary Lancaster led the band. He was followed by Darrell Zeller, who led the band from 1943 until 1989. George McDowell led the band from 1989 until 1995.

Now in its 138th year, the Arion Band continues playing each summer season from mid-May through mid-September. During the season, they will play around 10 performances. They stay local playing at festivals, nursing home, and sporting events. Practices are held in the Arion Band Hall on Uhl Street, which was built in 1900.

“The furthest we’ve ever traveled since I’ve been a member is Altoona to play for at an Altoona Curves baseball game,” Knouse says.

However, the band did travel by train to Luray, Va., where it performed in the caverns, according to Stevens’ history.

The band gets its name from the ancient Corinthian, Arion He was a poet who was known for his musical invents, including the dithyramb. He is also remembered for the Greek myth of being kidnapped by pirates and thrown overboard, only to be rescued by dolphins.

All of the members are volunteers, who participate because they love playing music. They range from middle-school students to retired musicians.

“We have a lot of nice history and multiple generations playing,” Knouse says. This includes a father and daughter who play trumpets, in-laws, aunts, and cousins from local families.

There was time in its early years when musicians had to try out for the band. Once in the band, there was competition to play in the first seat for a particular instrument. This meant that musicians were serious about their practicing.

“If you were talking, they could hold your instrument for a week so that you couldn’t practice,” says Vice President Jeanette Tucker.

In modern times, the band has been open to anyone who has a desire to play music.

“We will work with whoever comes to play,” Tucker says. “The ones who don’t fit in kind of weed themselves out.”

She joined the band 19 years ago after she heard them performing at the Frostburg Soapbox Derby Day.

“I heard them play and I thought, ‘That’s what I want to be a part of,’” Tucker says.

Any money the band gets from its performances are used to pay the band’s expenses, such as travel and hall upkeep.

“We keep going because we have a sense of responsibility to keep the tradition alive and keep it going,” Horner says.

One way the band keeps that tradition alive is through their music choices. Horner’s job as director is to find the music that will appeal to the audiences that they play for. This has led to an evolving repertoire that remains top quality.

The musicians themselves are another reason for the longevity of the band. Once members join, they tend to remain with the band because it is fun and they form close relationships with the other members.

“We create something together that no one can do individually,” Horner says.