James Rada Jr.'s Blog, page 13

January 12, 2017

Get “The Man Who Killed Edgar Allan Poe” FREE until Jan. 13

[image error]If you’re a fan of Edgar Allan Poe, The Man Who Killed Edgar Allan Poe solves the mystery of the great writer’s murder, and you can get it FREE on Kindle until Jan. 13.

You might be thinking that Poe wasn’t murdered. He died in a hospital. You’re wrong.

While he did die at the Washington Medical Center, before that, he was found delirious on the streets of Baltimore and wearing clothes that were not his own. He was admitted to the hospital where he died without explaining what had happened to himself. One clue to what happened to him was that he shouted the name “Reynolds” before he died.

The hospital and its records were later destroyed in a fire, so we’re left with theory and conjecture about how the Master of the Macabre died. One person knows how the Father of the Modern Mystery died, and that person is …

The Man Who Killed Edgar Allan Poe.

This is his story, although it reads like one of Poe’s horror tales.

Alexander Reynolds has been known by many names in his long life, the most famous of which is Lazarus, the man raised from the dead by Christ. Matthew Cromwell is another resurrected being living an extended life. Eternal life has its cost, though, whether or not Alexander and Matthew want to pay it.

Alexander has already seen Matthew kill Edgar’s mother and he is determined to keep the same fate from befalling Edgar.

From the time of Christ to the modern days of the Poe Toaster, The Man Who Killed Edgar Allan Poe is a sweeping novel of love, terror, and mystery that could have come from the imagination of Edgar Allan Poe himself.

From the reviewers:

“Impressively original, exceptionally well written, absolutely absorbing from beginning to end, ‘The Man Who Killed Edgar Allan Poe’ showcases author J. R. Rada’s outstanding skills as a novelist. ” – Reviewer’s Bookwatch

“…this fictional nail-biting account of the two men whose blood feud brought about Edgar’s death. … it’s a great ride through suspense, horror, and mystery – worthy of the writer for whom the novel takes license.” – Allegany Magazine

You might also like these posts:

REVIEW: Liar, Temptress, Soldier, Spy: Four Women Undercover in the Civil War by Karen Abbott

REVIEW: Six Frigates by Ian W. Toll

REVIEW: The Murder of the Century: The Gilded Age Crime That Scandalized a City & Sparked the Tabloid Wars by Paul Collins

January 5, 2017

This restaurant, which is as old as the U.S., used to be a stop on the Underground Railroad

[image error]While the Founding Fathers were working to build a nation in Philadelphia in 1776, in south-central Pennsylvania (Adams County, Pa. wasn’t created until 1800), Rev. Alexander Dobbin and his parishioners were building a house that, just like the United States, is still standing more than two years later.

Though now surrounded by houses, businesses, hotels and monuments in Gettysburg, when the house was built, it was a 300-acre farm.

The Dobbin Family

Alexander Dobbin was born in Ireland in 1742. After studying the classics in Ireland, Dobbin and his wife, Isabella Gamble, left Ireland to settle in America. In America, Dobbin became pastor of the Rock Creek Presbyterian Church, located one mile north of what is now Gettysburg.

In 1774, the Dobbin purchased 300 acres of land in and around what is now the town of Gettysburg. At one point, he was the second-largest landholder in the area behind Gettysburg founder James Getty.

[image error]The original stone structure was home to Dobbin’s wife, 10 children and 9 step children. Isabella died at a young age and Dobbin married Mary Agnew who had 9 children.

The house also served as a Classical School, which was a combined seminary and liberal arts college. “Dobbin’s school was the first of its kind in America west of the Susquehanna River, an academy which enjoyed an excellent reputation for educating many professional men of renown,” according to the Dobbin House brochure.

Dobbin also worked to establish Adams County as separate from York County. Once it happened, he was appointed one of the two commissioners who helped chose Gettysburg as the county seat of the new county.

The house passed out of the Dobbin family in 1834 and began being passed through a series of owners. Conrad Snyder owned the house during the Civil War.

Dobbin House on the Underground Railroad

[image error]During the Battle of Gettysburg, Beamer said, “There was substantial fighting nearby. It was amazing that it didn’t take a cannonball hit.”

The house was also used as an Underground Railroad stop. Slaves were hidden in a crawl space between the first and second floors behind a false wall. The space can still be seen today when touring the house.

The Many Uses of the Dobbin House

The house served as a private residence or apartments until the 1950’s. From the 1950’s until 1975, the building was a museum, gift shop and housed a diorama on the second floor.

The current owners purchased the house in 1975 and opened the Springhouse Tavern in May 1978. That evolved over the years growing into a complex that includes the tavern, a fine-dining restaurant in the actual Dobbin House, a banquet room, gift shop and bed and breakfast that serve more than 200,000 guests each year.

“We strive to serve quality food and offer gracious service,” Beamer said.

It’s all done in the setting of an authentic colonial tavern that offers recipes that have been featured in “Bon Appetit” and “Cuisine” magazines.

The Dobbin House is also on the National Register of Historic Places.

For more information, visit the Dobbin House web site.

December 29, 2016

1925 tornado left thousands dead and injured

[image error]

A mid-afternoon tornado on March 18, 1925, left a killing swath in its wake.

The tornado actually traveled through five Midwest states, but it was three Illinois towns that bore the brunt of the destruction. “Where it did the worst damage the tornado lasted less than five minutes,” reported the Ada (OK) Evening News.

Tornado Arrives

The tornado came out of the Ozark Mountains in mid-afternoon. This is a bad hour for a tornado to hit because schools and businesses are packed with people. This proved to be the case with this tornado as well.

Its main path was measured at around 200 miles long, but this tornado took erratic and deadly detours before returning to the main path. When the distances traveled on the offshoots was added in, the total mileage was around 700 miles.

[image error]

The destruction of Griffin, IN, after the 1925 tornado swept through.

The Destruction

The Ada Evening News described the destruction in this way: “It flattened heavily constructed school and business buildings with worse results than in lighter dwellings.

“Babies in homes were special sufferers.

“Fires still raging or smouldering and millions of dollars worth of wreckage delayed counts of the larger death lists.

“The hardest hit places were three small-cities in southern Illinois, West Frankfort, Murphysboro and Carbondale.

“Nearly all the destruction was in the soft coal fields.

“Next to Illinois the worst sufferers were in Indiana and Missouri with fatal results of the tornado reaching Tennessee and Kentucky.”

In DeSoto, IL, the tornado flattened a school with 250 students in it. Only three escaped without injury and 88 were killed. In the entire town, only five buildings were left standing.

“So terrific was the force of the storm that bodies were reported carried a mile while timbers from the wrecked town of DeSoto, Illinois were found in DuQuoin 15 miles away,” reported the Ada Evening News.

In the town of Parrish, IL, only three people in a town of 500 escaped injury.

Aftermath

The tornado traveled through five states – Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Tennessee and Kentucky – and killed people in 26 towns.

The tornado left many fires in its wake, which hampered the efforts of rescuers.

Around 1000 people were killed and 3000 injured. About 10000 were left homeless by the tornado.

The Red Cross moved in following the tornado to offer help. Relief trains were sent and many people sent donations. The day after the tornado the Illinois Legislature authorized $500,000 in relief aid.

“As reports from various sections were gathered today no doubt was left that the disaster is the worst of its kind in the country’s history. The greatest death toll previously taken by a cyclone was in 1908 when five hundred were killed in Mississippi, Louisiana, and Alabama.

“The terrific blow of yesterday was followed today by high winds in Pennsylvania. Michigan and Northern New York,” reported The Sheboygan (WS) Press.

Total damage was estimated at well over $10 million.

December 22, 2016

Civilian POWs return home

This is the third in a series of articles about the civilians who were taken as prisoners of war by the Confederate Army after the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863.

[image error]

Salisbury Prison for Union soldiers in North Carolina.

Eight civilians from Gettysburg were arrested during the 1863 battle, taken south, and imprisoned in POW camps where they endured brutality and starvation.

The arrested men were George Codori, J. Crawford Guinn, Alexander Harper, William Harper, Samuel Pitzer, George Patterson, George Arendt, and Emanuel Trostle.

“Both Pennsylvania and the U. S. government informed the Confederacy that they had taken noncombatant civilians, and demanded their return. Because it refused, and since it was regarded as an act of state terrorism, the U. S. Secretary of War ordered the U. S. Army to seize 26 Confederate civilians and hold them as counter hostages at the Fort Delaware Prison on the Delaware River,” according to the Gettysburg Times.

The fort is on Pea Patch Island in the Delaware River between Delaware and New Jersey. It had granite and brick walls that ranged in thickness from seven to 30 feet and were 32 feet high. Conditions for prisoners there were unpleasant, although not as unpleasant as things had been in Salisbury Prison for the Gettysburg civilian prisoners.

One Union doctor wrote of his visit to the prison and was recorded in The War Of The Rebellion: A Compilation Of The Official Records Of The Union And Confederate Armies. “The barracks were at that time damp and not comfortably warm, and I suspect they have been so a part of the time during the winter…Some, perhaps a large majority, were comfortably clad. Some had a moderate and still others an insufficient supply of clothing. The garments of a few were ragged and filthy. Each man had one blanket, but I observed no other bedding nor straw. Nearly all the men show a marked neglect of personal cleanliness. Some of them seem vigorous and well, many look only moderately well, while a considerable number have an unhealthy, a cachectic appearance.”

In early 1865, the Gettysburg civilian POWs finally got their hearing before General Winder in Richmond. “He called some of us disloyal Pennsylvanians. I told him I was loyal to the backbone,” Samuel Pitzer wrote after the war.

This led to their release and they began returning home to Gettysburg in the middle of March 1865.

The return of the prisoners was a surprise to many because most of them had been presumed dead after the battle. Emanuel Trostle’s wife hadn’t given up hope that her husband still lived and was rewarded for her dedication when he returned home. He went on to lead a successful life as a shoemaker and a farmer.

He died in 1914 at the age of 75. He would have been alive to see the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg and perhaps, the same men who had captured him during the battle. It is not known whether he attended the reunion, though.

George Cordori’s return on March 13 got a small mention in the Adams Sentinel. The joy of his return lasted only two weeks. He died of pneumonia at the age of 59.

“For a number of years he had had an attack of this dangerous disease almost every winter, but during the past 18 months, though suffering the privations incident to the life of a prisoner of the South, he informed us his health was very good,” the Gettysburg Compiler reported. It is believed he caught a cold riding the crowded transport that brought freed prisoners to Annapolis and dropped them off.

Ironically, three days after Codori died, the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and Senate released a joint resolution asking “That the Secretary of War be respectfully requested to use his utmost official exertions to secure the release of J. Crawford Gwinn, Alexander Harper, George Codori, William Harper, Samuel Sitzer (sic), George Patterson, George Arendt, and Emanuel Trostle, and such other civilians, citizens of Pennsylvania, as may now be in the hands of the rebels authorities, from rebel imprisonment and have them returned to their respective homes in Pennsylvania.”

Here are the other parts of the story:

Confederate Army takes civilian prisoners after the Battle of Gettysburg (part 1)

Gettysburg civilians endure horrors of POW camps (part 2)

December 15, 2016

Gettysburg civilians endure horrors of POW camps

This is the second in a series of articles about the civilians who were taken as prisoners of war by the Confederate Army after the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863.

[image error]When the Confederate Army left Pennsylvania at the end of the Battle of Gettysburg, they left with eight civilians. These men had done nothing wrong except be in the wrong place at the wrong time. They were captured at different locations around Gettysburg on the suspicion that they were spies for the Union Army.

They weren’t.

They were ordinary citizens caught in the middle of a great battle.

The arrested men were George Codori, J. Crawford Guinn, Alexander Harper, William Harper, Samuel Pitzer, George Patterson, George Arendt, and Emanuel Trostle.

Samuel Pitzer was a Gettysburg farmer who had been arrested on July 2. He wrote that the prisoners were first sent to Castle Lightning prison in Richmond where all of their money except for two cents, their knives and their blankets were taken.

They were then moved to Libby Prison. Pitzer was upset that his hat was stolen there, which he said would have been worth $150 to $200 in Confederate dollars.

“The first thing we hear when new prisoners came in was ‘Fresh Fish,’ to which another would immediately reply ‘Scale him,’ and it was not long they had them all scaled,” Pitzer wrote.

The rations were poor, so much so that even the pigs ate better.

“They raise beans down there on which they fatten their hogs,” Pitzer wrote. “We got a broth with about a dozen of these beans and a little corn bread.”

After a time, they were sent to Castle Thunder Prison where the rations were even worse.

The commander there was a Union army deserter named George Edwards. He had a reputation for brutality. Pitzer wrote that he would make the prisoners stand around him while he swung his sword back and forth coming close to slicing the prisoners open.

After two months in Richmond, the prisoners were sent further south to Salisbury, N.C., where they were imprisoned in an old tobacco factory. At first, there were 500 prisoners in the factory prison, but during October 1863, that number swelled to 14,000.

What little food the prisoners received had a lot to be desired. In the beginning, their rations consisted of a little meat that was “strong and so full of worm holes that we could see through it,” according to Pitzer.

Other days, the guards simply threw a little beef and tripe into the garrison and let the prisoners fight over who got to eat it.

Sometimes the prisoners weren’t fed for two or three days at a time. It was a tactic used to encourage them to join the Confederate army so they could be sent to guard forts and camps.

The prisoners got to the point that they were eating just about anything they thought would fill them up.

“They ate rats, cats and dogs and I saw an Irishman eating the graybacks as he picked them from his clothes,” Pitzer wrote.

Within four months that 14,000 number had dwindled to 4,500 as men died from malnutrition.

“As regularly as the day returned from forty to sixty died,” Pitzer wrote.

The dead were buried in a common grave four bodies deep.

The Gettysburgians endured, though, not knowing when the end would come, but knowing that it would come eventually.

Here’s are the other parts of the story:

Confederate Army takes civilian prisoners after the Battle of Gettysburg (part 1)

Civilian POWs return home (part 3)

December 8, 2016

First Woman Executed in the Electric Chair

On March 20, 1899, Martha Place earned her place among the infamous by becoming the first woman executed in the electric chair.

On March 20, 1899, Martha Place earned her place among the infamous by becoming the first woman executed in the electric chair.

Martha Place was put to death in Sing Sing Prison’s electric chair on March 20, 1899 after having murdered her stepdaughter and trying to murder her husband. The double murder was shown conclusively to have been planned by Place and yet, her death elicited sadness among many, including the prison warden.

The First Woman Executed by Electrocution

Martha Place was led into Sing Sing Prison’s death chamber and strapped to the electric chair. An electrode was placed on a shaved area on the crown of her head and one on her calf.

“Mrs. Place went calmly to the chair. She leaned on Warden Sage’s arm. Her eyes were closed, and she seemed neither to seem nor to hear. She murmured a prayer,” reported the Portsmouth Herald.

She wore a plain black dress she had made herself.

“It was her expectation to wear this dress when she emerged from the penitentiary, either as a free woman or to return to Brooklyn for a new trial,” the Marion Daily Star reported.

Her last words as she sat down were, “God help me.”

More than 1700 volts were sent through her body, killing her instantly at 11:01 a.m. One report noted how the only sign of pain was how her lips pressed together.

“It was almost a smile, as she died,” the Portsmouth Herald reported.

Why She Was Executed

William Place lived in Brooklyn with his daughter Ida. About 18 months after the death of his first wife, he hired Martha as a housekeeper. They were married two months later.

“As long as she was housekeeper, it is said, she was extremely kinds to place’s daughter Ida, but she became quite a different person when place married her,” the Portsmouth Herald reported.

Martha was jealous of the close relationship between her husband and stepdaughter, which led to quarrels between the three of them. In addition, William wouldn’t let Martha’s son from her first marriage come to live with them.

And so, on February 8, 1898, after planning what she would do, Martha Place attacked her 22-year-old stepdaughter. She threw carbolic acid in the young woman’s face and then struck her senseless with an axe. She then carried the woman to the bed and smothered her with a pillow.

Following that, she lay in wait for her husband to return. When he did, she attacked him with the axe.

She injured him and he lost consciousness, but not before his screams alerted the neighbors. When the police broke into the house, they found Martha unconscious on an upstairs bed in an apparent suicide attempt.

The husband recovered and identified his wife as his attacker. Further, it was shown that Martha had written to her brother outlining her plan and telling him that she would be coming to live with him.

The Trial and Appeals

Judge William Hurd sentenced her to death after her trial and she fainted when she heard the verdict. Martha Place was sent to Sing Sing Prison on July 21, 1898, and wept as she entered.

She appealed the decision, but did not win.

Gov. Theodore Roosevelt of New York would not commute Martha’s sentence. He wrote in his statement, “This murder was one of peculiar deliberation and atrocity. To interfere with the course of the law in this case would be justified only on the ground that never hereafter, under any circumstances, should capital punishment be inflicted upon any murderess, even though the victim was herself a woman, and even though that victim’s torture preceded her death. There is but one course open to me. I decline to interfere with the course of the law.”

And so, Martha became the 26th person to die in Sing Sing’s electric chair.

You might also like these posts:

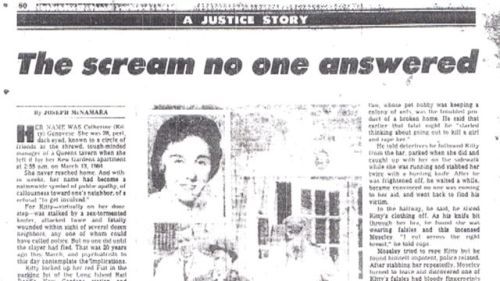

Murder Witnessed By 38 People Who Ignored Her Scream For Help

Ex-LAPD detective believes his father committed the Black Dahlia murder

Embarrassed wife has Oakland’s first doctor executed

December 1, 2016

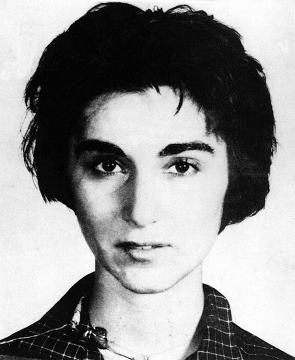

Murder Witnessed By 38 People Who Ignored Her Scream For Help

Catherine (Kitty) Genovese

On March 27, 1964, Catherine (Kitty) Genovese returned home from her work managing a Queens bar. It was around 3:20 a.m. when she parked her car and walked toward her apartment in the Kew Gardens neighborhood of Queens, New York.

The Attack on Kitty Genovese

She noticed a man loitering nearby who soon moved to intercept her. The man attacked her and she screamed. Lights in the nearby apartments came on and people looked outside.

“Oh, my God, he stabbed me! Please help me! Please help me!” Genovese screamed.

A man yelled from one of the apartments, “Leave that girl alone!”

The attacker ran off and the neighbors went back to bed.

The Murder of Kitty Genovese

A short time later the killer returned and attacked Genovese again and again she screamed. Lights in nearby apartments came on and once again people looked out at the attack. This time the killer the killer succeeded and murdered and raped Genovese.

One person did call police who arrived within two minutes, but by then it was too late. Genovese died on the ambulance ride to the hospital.

When witnesses were questioned as to why they did nothing, the most-common response was that they didn’t want to get involved.

Assistant Chief Inspector Frederick Lussen said, “ a phone call (during the attack) would have saved the girl’s life.”

The Murderer

Winston Moseley, 29, was arrested for the murder. He was a business machine operator who was arrested later on burglary charges. He confessed to the Genovese murder and two others that also involved sexual assault. Psychiatric exams suggested he was a necrophile. He was convicted of murder and sentenced to death.

Married, Moseley had gotten up at 2 a.m. that night, left his wife sleeping and set out to kill a woman. He found Genovese.

Though his own testimony at his trial proved he was the murderer, his death sentence was reduced to a life sentence in 1967. He tried to escape from prison in 1968, managing to take five hostages and rape one of them before being recaptured.

He was denied parole for the thirteenth time in March 2008.

Response to the Murder

In the weeks following, the murder of Kitty Genovese was not the story so much as the witnesses lack of help. The United Press International report read, “38 residents of a middle class New York neighborhood watched a killer stalk a 28-year old woman for more than 30 minutes before he killed her and none of them even called for help.”

The country’s shock at how witnesses failed to help Genovese led to a nationwide effort, particularly in New York City, to fight apathy about crime.

Started campaign against apathy against crime

How the story has changed

As more investigations and evidence have come to light about the story, it has altered somewhat. For instance, it was originally reported that Moseley made three attacks against Genovese. It is now known that they were only two attacks. Also, though it was originally reported that 38 people saw the murder, it is now believed that the number was around 12 and none of them saw the entire attack.

Other posts that you might be interested in reading:

Bessie Darling’s murder haunts us still

Death in a bottle: the mysterious unsolved Tylenol murders.

C&O Canal murder mystery has surprising solution

November 24, 2016

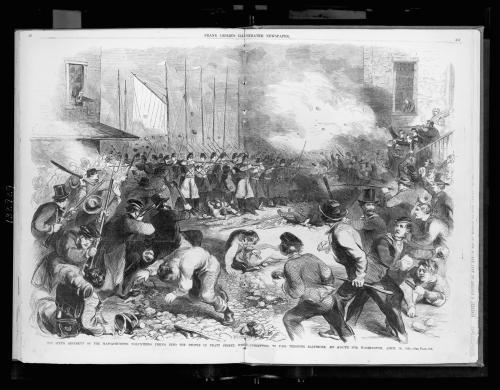

War in the Streets: The Civil War’s First Casualties Died on Pratt Street

The Sixth Massachusetts Regiment wasn’t looking for trouble when they came to Baltimore in April 1861. The city wasn’t even their destination. They were traveling to Washington, D.C., but there was no direct railroad connection between Massachusetts and Washington. The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad ended at President Street Station. Horses then had to pull the rail cars 10 blocks along Pratt Street to Camden Station and onto the rails of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The Sixth Massachusetts Regiment wasn’t looking for trouble when they came to Baltimore in April 1861. The city wasn’t even their destination. They were traveling to Washington, D.C., but there was no direct railroad connection between Massachusetts and Washington. The Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad ended at President Street Station. Horses then had to pull the rail cars 10 blocks along Pratt Street to Camden Station and onto the rails of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad.

The soldiers were answering the request of President Abraham Lincoln who had called for 75,000 troops to put down rebellion that began at Fort Sumter a week earlier. The call had only encouraged the Confederacy. What had been seven Confederate states quickly grew to 11 and many Marylanders wanted their state to be the 12th. These people saw the arrival of Union troops, even those passing through, as a foreign invasion.

With tensions high, the Baltimore Police escorted the Massachusetts troops as they transferred between stations. Nine rail cars were allowed to pass over the Jones Falls bridge with little but catcalls like “Let the police go and we’ll lick you” or “Wait till you see Jeff Davis” harassing them.

When the tenth car approached the bridge, someone in the gathering mob managed to throw the brake on the car and stop it. The crowd then pelted the rail car with paving stones as the soldiers within took cover.

The crowd quickly grew to 800 people who began to tear up the street and tracks with shovels and picks. With no way to continue, the soldiers were faced with marching through the growing mob in order to get to Camden Station. However, the mob had continued to grow both in size and anger. It was now estimated to be 2,000 people strong.

When the troops didn’t leave the relative safety of the rail car, the mob prepared to storm it. They were only stopped by the Baltimore Police who rushed in force to put themselves between the crowd and the rail car.

With the tracks blocked, the troops had no choice but to disembark into the hostile crowd. They formed ranks and began to slowly push their way toward the Camden Street station. The mob wasn’t willing to let them go so easily, though. The soldiers tried to march in one direction and were blocked by an unyielding crowd. When they reversed direction, the mob blocked them in that direction, too.

“Then the crowd pressed stronger, until the body reached the corner of Gay street, where the troops presented arms and fired,” according to an eyewitness account published in The Sun. “Several persons fell on the first round, and the crowd became furious. A number of revolvers were used, and their shots took effect in the ranks.”

Chaos reigned as people scattered, yelling and trampling each other. The police efforts were overwhelmed within minutes as they lost control of the situation.

The soldiers now found themselves in a running fight with the mob as they tried to reach Camden Station. The mob continued throwing bricks and stones and some even got a hold of weapons and fired toward the soldiers.

“After firing this volley the soldiers again broke into a run, but another shower of stones being hurled into the ranks at Commerce street with such force as to knock several of them down, the order was given to another portion of them to halt and fire, which had to be repeated before they could be brought to a halt,” according to The Sun. “They then wheeled and fired some twenty shots, but from their stooping and dodging to avoid the stones, but four or five shots took effect, the marks of a greater portion of their balls being visible on the walls of the adjacent warehouses, even up to the second stories. Here four citizens fell, two of whom died in a few moments; and the other two were carried off, supposed to be mortally wounded.”

One soldier who was brought down by the mob begged for his life, saying “he was threatened with instant death by his officers if he refused to accompany them. He said one-half of them had been forced to come in the same manner, and he hoped all who forced others to come might be killed before they got through the city.” Whether he spoke the truth or just hoped to win his life is not known, but the mob took no further action against him.

One soldier who was brought down by the mob begged for his life, saying “he was threatened with instant death by his officers if he refused to accompany them. He said one-half of them had been forced to come in the same manner, and he hoped all who forced others to come might be killed before they got through the city.” Whether he spoke the truth or just hoped to win his life is not known, but the mob took no further action against him.

The soldiers eventually reached Camden Station and the police formed up their own ranks to block the mob. The troops were alive but they had lost much of their equipment and some of their wounded, who they had been forced to leave behind.

The small battle left four soldiers and 12 civilians dead. It is not known how many civilians were wounded but 36 soldiers were left behind to be treated. One of the dead soldiers, Corporal Sumner Henry Needham, is sometimes considered to be the first Union casualty in the Civil War, though he was killed by civilians.

Though the Maryland legislature voted against secession on April 26, it had to meet in Frederick to do it for fear of inciting another riot. Union troops were also deployed throughout the state to ensure that it remained within the Union. Confederate sympathizers like the mayor of Baltimore and the police commissioner were imprisoned in Fort McHenry.

The most-lasting effect of the riot is that it inspired James Ryder Randall to write “Maryland, My Maryland,” a strongly Southern supporting song, which eventually became the state song.

November 18, 2016

Historic Photo: Banana docks, East River, New York, circa 1900, colorized.

Marina Amaral’s colorization work is amazing. It looks authentic and so eye catching.

This absolutely jaw-dropping photo is exactly the kind of history I love to see the most: a real, genuine piece of the past that has been made vivid, real and accessible in a way that speaks to us today very powerfully. In this photo, taken between 1890 and 1910 (my guess is it’s around 1900), a ship carrying bananas from Central or South America has just docked at a pier in the East River in New York City and fruit agents–the men in suits–are already haggling for deals, even before the bananas themselves have been unloaded. Carts are ready to haul the fresh fruit away to marketplaces, most of them probably not too far away from this site. In the meantime, lots of other commerce is going on, and you can see the buildings of Manhattan rising in the background. This is a very evocative image that speaks to the…

View original post 276 more words

Historic Photo: Men of the Depression, 1939, by Dorothea Lange, colorized.

Brazilian digital colorist Marina Amaral has done a magnificent job of bringing this 1930s photo to life.

Source: Historic Photo: Men of the Depression, 1939, by Dorothea Lange, colorized.