Two trains collide in Ransom

Editor’s Note: This is the second in a series of three articles about the great Ransom train wreck in 1905.

Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

On June 17, 1905, around 5:55 p.m., near Ransom, a little village southeast of Patapsco, Md., in Carroll County, the Blue Mountain Express and a freight train collided head-on.

“Just west of the bridge, they came together with terrific force, the three engines being piled one upon another, fortunately in such a manner that sufficient steam connections were broken, to relieve the boilers, and thus prevent the further horror of one or more explosions,” reported The Washington Post.

“After the freight train whizzed past Patapsco, it was only a couple of minutes and it sounded like the whole train rolled down the track. The noise was terrific! I never heard such an awful noise like that!” said 13-year-old Emil A. Caple who was walking near the tracks on his way to the Patapsco Post Office and General Store.

George C. Buckingham was a conductor on the freight train. He had just looked at his pocket watch and thought the train would be able to make up the five minutes it was running behind. As he put his watch back in his pocket, he felt “the awful plunging jar, crash and grind of wood and steel.”

“There was no time to move. The man ahead of me, a Washington doctor, dived out of his window; we were two seats from the front of the first coach, and I sprang to my feet and amid the groans and shrieks of the injured, I made my way out,” Cunningham told the Hagerstown Daily Mail.

The Frederick Daily News reported that the men who were sitting on the bumper suffered the greatest casualties.

“When the crash came the more fortunate, who were on the engine, jumped or were thrown from the train and were only injured. Those in the baggage car were terribly mangled, and the crews of all three engines were killed. Their bodies all believed to be under the wreckage of the engines,” reported The New York Times.

Flagman George Lynch was at the back of the freight train at the time of the collision. He was the only one of the nine crew members on the three engines to survive.

“There was a jar and then a succession of bumps, but I was not thrown down,” Lynch said.

Despite the impact of the engines in which “the three steam monsters were reduced to scrap iron,” none of the passenger coaches derailed. They all survived because of this, and “none of the passengers were injured aside from slight cuts, bruises and shocks,” according to one newspaper report.

Caple said that everyone who had heard the wreck came running. “I ran right along with them as fast as my legs could carry me. On the way down, we passed a man with a railroad flag in his hand running towards the Patapsco store. Somebody asked him, ‘What happened?’ He said, ‘My god, I don’t know.’ He ran up the track to telephone Westminster,” Caple said.

When Caple arrived at Ransom, it was hard for him to see the actual wreck because of all the steam escaping from busted engines and what he did see, he wished he hadn’t.

“People were crawling from the wreck scalded. Some were laying with arms and legs chopped off and screaming and crying were terrible. Carloads of lard in wooden barrels had burst open and many passengers were covered with it and rescue crews had to work in it up to the knees to pull people out. They told all of us to either help or we would have to leave. So no matter what age, every one of us pitched in to help.

“I helped pick up arms and legs. No one knew for sure who they belonged to, so they told us to give them to anybody who didn’t have one that it looked like they belonged to. I helped another man who was scalded. He kept crying that he was so cold, so I got a coat and put over him. They said he had been scalded inside and I believe he died.

“The whole bottom just west of the Patapsco River was strewn with wreckage and bodies and people calling for help.”

Westminster knew of the crash minutes after it happened. Captain H. Clay Eby, a former conductor on one of the trains involved in the crash, lived near the crash site. Though he couldn’t see the collision, he had recognized the sound and what it meant. He had a telephone in his house, so he called E.O. Grimes, the railroad agent in Westminster, and alerted him to the collision.

Once news of the wreck got out, a relief train was put together at Westminster and sent out to help. The injured were taken by train to a hospital in Baltimore. “Just before the first relief train taking the injured to the hospitals of Baltimore left the wreckage began to burn.” Ambulances were also ordered to the scene. An express train following the freight train acted as a relief train for the other side and the passengers on both trains gave all possible aid to the victims.

George Stimmel, a laborer from Thurmont, was one of the passengers taken out of the wreck alive. He was taken to the Hotel Albion in Westminster, but he died the next morning. While on the relief train to Westminster, he “offered a touching and pathetic prayer for his wife and children, pleading earnestly that they might be supported by Almighty God and that the wife might be enabled to train up the children in the paths of christianity and righteousness.”

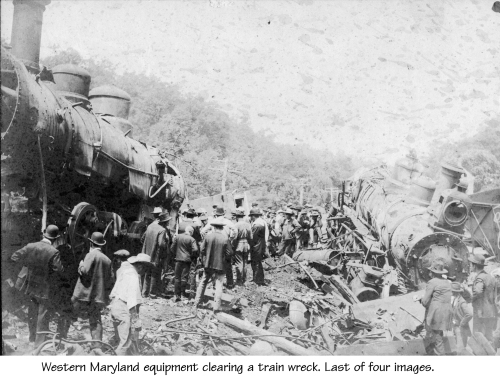

About 75 men from the Western Maryland and Northern Central railroads used two steam cranes to clear away the wreckage. “With two great steam cranes the three engines were righted and placed upon the tracks, then slowly towed down to the siding near Lawndale. The overturned cars, the broken and twisted axles and machinery were hauled out of the way, and watches, pocketbooks, blank books and other effects belonging to the victims of the wreck were collected,” reported The Catoctin Clarion.

Here are the other parts of the story:

On the road to disaster (part 1)