On the road to disaster

Editor’s Note: This is the first in a series of three articles about the great Ransom train wreck in 1905.

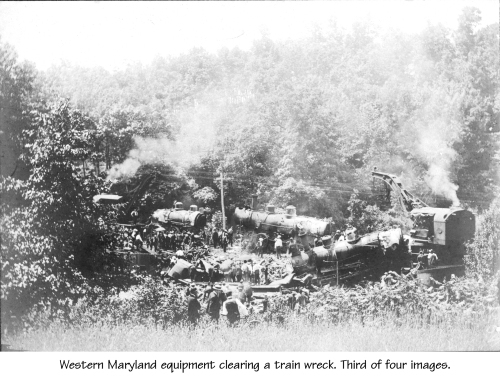

Courtesy of Thurmontimages.com.

Perhaps the railroaders’ minds were on a tomorrow they would never see. Such thinking might, in part, explain some of their actions on June 17, 1905.

The Western Maryland Rail Road train schedule would change on Sunday, June 18, 1905, but that was tomorrow. On Saturday, June 17, Flagman George Lynch and other members of the freight train crew were waiting with their train on a siding at Gorsuch, Maryland.

Lynch’s eastbound train had pulled onto the siding at 4:25 p.m. to wait for three westbound trains to pass.

“While we were waiting we all got down from the train and sat on a pile of ties near the track. The two engineers and the conductors had their time cards and schedules and we talked for awhile about the time we were making, how long we had to wait for No. 5 and where we would run to after she passed,” Lynch recalled for the Catoctin Clarion.

Drawn by engines 41 and 43, Lynch’s freight train was 18 cars long and heavily laden with coal. Once the three westbound trains had passed, the line would be open for Lynch’s train to continue its eastbound journey to Baltimore, but with only one set of tracks to travel, the other trains had priority.

The crew waited for “considerably” more than an hour. The Union Bridge Accommodation, No. 17, passed on time. Then came the No. 11 Blue Mountain Express, also on time for its first trip of the season.

Lynch retold the events that followed to a newspaper reporter for the Catoctin Clarion.

With a few minutes left before the third westbound train, the No. 5 Thurmont Express, was scheduled to pass, Lynch walked away from the group to get some water at a nearby spring. When he returned, the engineers were in their respective engines. The firemen were shoveling coal into the fires to build up a head of steam.

“Jump on board if you’re going,” one of the engineers called.

Lynch looked at his watch once again. By his reckoning, they still had a few minutes before the train could leave, but he wasn’t going to be left behind. He grabbed a handrail and pulled himself aboard the moving train.

“Where are you fellows going to pass the No. 5?” Lynch called to the fireman.

“At Lawndale,” was the answer he thought he heard over the noise of the steam engine gathering speed.

Lynch couldn’t believe the answer. There wasn’t enough time to get to Lawndale if the No. 5 hadn’t already passed.

“For God’s sake, look at your watch!” Lynch shouted.

The fireman waved his hand at Lynch as if nothing was wrong. Lynch wondered if his watch was simply wrong.

“There were two engineers, the two conductors, and the fireman, five in all, who had the time and knew the schedules as well as I did,” Lynch said.

“Evidently, the engineers or conductors had gotten confused as to how many trains went by,” said local Thurmont historian and train enthusiast George Wireman in a 2005 interview. “But how they could get so mixed up about ordinary work has been a question mark for years.”

One suggestion raised by The Washington Post was, “The fact that a new schedule goes into effect tomorrow may have caused some confusion.” The new schedule had the westbound No. 5 nine minutes slower in reaching Westminster, Md., because a stop in Glyndon, Md., was added. If the crew was thinking that day that the No. 5 was on the new schedule, then they would have thought the train was further east, possibly about 4.5 miles further east than it was. Had this been the case, the freight train would have had time to reach the Lawndale siding.

Another possibility is that since the Blue Mountain Express was making its first run of the season that day, the crew might have been expecting only two trains and not three. However, according to Lynch’s version of events, the crew knew a third train was coming and thought they would have time to pull over.

Lynch said in the Frederick Daily News that he considered pulling down the air brakes, but he deferred to the greater experience of the other crewmen.

The No. 5 had left Hillen Station in Baltimore City, Md., on time at 5 p.m. About 100 passengers were aboard. The train had three passenger coaches and a baggage combination car. Most of the passengers sat in the coaches. It was eating up the route at 30 miles per hour.

The baggage car was filled with railroad workers, many of whom lived in Thurmont, Md. and Catoctin Furnace, Md., two towns next to each other in northern Frederick County. The workers – they were called “floaters” because they traveled to where they were needed to work – had boarded the train at Mount Hope, Md., where they had been working to repair the damage from a small freight wreck there during the week prior. The train was so crowded that some of the men had to sit on the bumpers between the baggage car and the engine tender and between the baggage car and the first passenger car.

It was a choice most of them would not live to regret.