Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 54

December 3, 2017

In The Shadow of Liberty- A 2018 Tayshas Reading List Selection

In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives was named to the 2018 Tayshas Reading List” by the Texas Library Association. The complete list can be found here.

The complete list can be found here.

November 28, 2017

Who Started the “War on Christmas?”

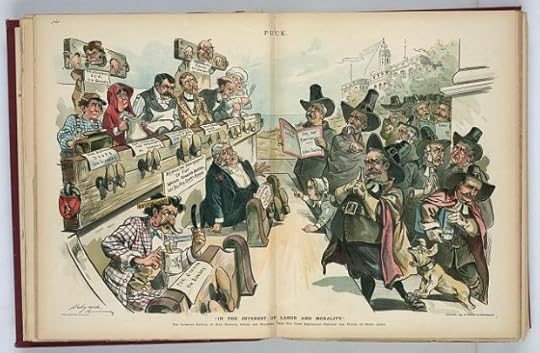

“In the interest of labor and morality” (1895: Image Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print)

(Revision of post first published 12.11.2103)

It’s that time of year. Cue the lights, decorations, music.… and the “War on Christmas.”

Proclaiming a secular assault on the religious significance of the holiday has become a seasonal staple, just like the Macy’s Parade with Santa Claus. The President made saying “Merry Christmas” a campaign issue and it has been a staple of conservative talk show hosts for years.

The basic premise: Christmas is under attack by Grinchy atheists and secular humanists who want to remove any vestige of Christianity from the public space. Any criticism of public displays devoted to religious symbols –mangers, crosses, stars — is seen by these folks as part of a wider attack on “Christian values” in America. Mass market retailers who substituted “Happy Holidays” for “Merry Christmas” are part of the conspiracy to “ruin Christmas.”

But in fact, most religious displays are not banned. Courts simply direct that one religion cannot be favored over another under the Constitutional protections of the First Amendment. Christmas displays are generally permitted as long as menorahs, Kwanzaa displays, and other seasonal symbols are also allowed.

In other words, the “War on Christmas” is pretty much a phony war. But where did this all start?

The first laws against Christmas celebrations and festivities in America came during the 1600s –from the same wonderful folks who brought you the Salem Witch Trials — the Puritans. (By the way, H.L. Mencken once defined Puritanism as the fear that “somewhere someone may be happy.”)

“For preventing disorders, arising in several places within this jurisdiction by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other communities, to the great dishonor of God and offense of others: it is therefore ordered by this court and the authority thereof that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon any such account as aforesaid, every such person so offending shall pay for every such offence five shilling as a fine to the county.”

–From the records of the General Court,

Massachusetts Bay Colony

May 11, 1659

The Founding Fathers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were not a festive bunch. To them, Christmas was a debauched, wasteful festival that threatened their core religious beliefs. They understood that most of the trappings of Christmas –like holly and mistletoe– were vestiges of ancient pagan rituals. More importantly, they thought Christmas — the mass of Christ– was too “popish,” by which they meant Roman Catholic. These are the people who banned Catholic priests from Boston under penalty of death.

This sensibility actually began over the way in which Christmas was celebrated in England. Oliver Cromwell, a strict Puritan who took over England in 1645, believed it was his mission to cleanse the country of the sort of seasonal moral decay that Protestant writer Philip Stubbes described in the 1500s:

‘More mischief is that time committed than in all the year besides … What dicing and carding, what eating and drinking, what banqueting and feasting is then used … to the great dishonour of God and the impoverishing of the realm.’

In 1644, Parliament banned Christmas celebrations. Attending mass was forbidden. Under Cromwell’s Commonwealth, mince pies, holly and other popular customs fell victim to the Puritan mission to remove all merrymaking during the Christmas period. To Puritans, the celebration of the Lord’s birth should be day of fasting and prayer.

In England, the Puritan War on Christmas lasted until 1660. In Massachusetts, the ban remained in place until 1687.

So if the conservative broadcasters and religious folk really want a traditional, American Christian Christmas, the solution is simple — don’t have any fun.

Read more about the Puritans in Don’t Know Much About® History and America’s Hidden History. The history behind Christmas is also told in Don’t Know Much About® The Bible.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

November 22, 2017

Two for Thanksgiving: Real First Pilgrims & Holiday’s History

Like the Macy’s parade, here is my Thanksgiving tradition. I post two articles about the holiday that I wrote for the New York Times.

The first, from 2008, is called “A French Connection” and tells the story of the real first Pilgrims in America. They were French. In Florida. Fifty years before the Mayflower sailed. It did not end with a happy meal. In fact, it ended in a religious massacre.

Illustration by Nathalie Lété in the New York Times

TO commemorate the arrival of the first pilgrims to America’s shores, a June date would be far more appropriate, accompanied perhaps by coq au vin and a nice Bordeaux. After all, the first European arrivals seeking religious freedom in the “New World” were French. And they beat their English counterparts by 50 years. That French settlers bested the Mayflower Pilgrims may surprise Americans raised on our foundational myth, but the record is clear.

The complete story can be found in America’s Hidden History.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

The second is “How the Civil War Created Thanksgiving” (2014) and tells the story of the Union League providing Thanksgiving dinners to Union troops.

Of all the bedtime-story versions of American history we teach, the tidy Thanksgiving pageant may be the one stuffed with the heaviest serving of myth. This iconic tale is the main course in our nation’s foundation legend, complete with cardboard cutouts of bow-carrying Native American cherubs and pint-size Pilgrims in black hats with buckles. And legend it largely is.

In fact, what had been a New England seasonal holiday became more of a “national” celebration only during the Civil War, with Lincoln’s proclamation calling for “a day of thanksgiving” in 1863.

Enjoy them both. Now for some football.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

November 10, 2017

11-11-11: Don’t Know Much About Veterans Day-The Forgotten Meaning

“The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.”

(This is a revised version of a post originally written for Veterans Day in 2011. The meaning still applies.)

Taken at 10:58 a.m., on Nov. 11, 1918, just before the Armistice went into effect; men of the 353rd Infantry, near a church, at Stenay, Meuse, wait for the end of hostilities. (SC034981)

On Veterans Day, a reminder of what the day once meant and what it should still mean.

That was the moment at which World War I –then called THE GREAT WAR– largely came to end in 1918, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

One of the most tragically senseless and destructive periods in all history came to a close in Western Europe with the Armistice –or end of hostilities between Germany and the Allied nations — that began at that moment. Some 20 million people had died in the fighting that raged for more than four years since August 1914. The formal end of the war came with the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

Besides the war casualties, an estimated 100 million people died during the war of the Spanish flu, a worldwide pandemic that was completely linked to the war and had an impact on its outcome. That is the subject of my forthcoming book, More Deadly Than War:The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War. (May 15, 2018)

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and World War I -Coming MAY 2018

The date of November 11th became a national holiday of remembrance in many of the victorious allied nations –a day to commemorate the loss of so many lives in the war. And in the United States, President Wilson proclaimed the first Armistice Day on November 11, 1919. A few years later, in 1926, Congress passed a resolution calling on the President to observe each November 11th as a day of remembrance:

Whereas the 11th of November 1918, marked the cessation of the most destructive, sanguinary, and far reaching war in human annals and the resumption by the people of the United States of peaceful relations with other nations, which we hope may never again be severed, and

Whereas it is fitting that the recurring anniversary of this date should be commemorated with thanksgiving and prayer and exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations; and

Whereas the legislatures of twenty-seven of our States have already declared November 11 to be a legal holiday: Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring), that the President of the United States is requested to issue a proclamation calling upon the officials to display the flag of the United States on all Government buildings on November 11 and inviting the people of the United States to observe the day in schools and churches, or other suitable places, with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

Of course, the hopes that “the war to end all wars” would bring peace were short-lived. By 1939, Europe was again at war and what was once called “the Great War” would become World War I. With the end of World War II, there was a movement in America to rename Armistice Day and create a holiday that recognized the veterans of all of America’s conflicts. President Eisenhower signed that law in 1954. (In 1971, Veterans Day began to be marked as a Monday holiday on the third Monday in November, but in 1978, the holiday was returned to the traditional November 11th date).

Today, Veterans Day honors the duty, sacrifice and service of America’s nearly 25 million veterans of all wars, unlike Memorial Day, which specifically honors those who died fighting in America’s wars.

We should remember and celebrate all those men and women. But lost in that worthy goal is the forgotten meaning of this day in history –the meaning which Congress gave to Armistice Day in 1926:

to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations …

inviting the people of the United States to observe the day … with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

The Library of Congress offers an extensive Veterans History Project.

The Veterans Administration website offers more resources on teaching about Veterans Day.

Read more about World War I and all of America’s conflicts in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

I discuss the role of Americans in battle in more than 240 years of American history in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah (Hachette Books and Random House Audio). My forthcoming book, MORE DEADLY THAN WAR: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War will be published in May 2018.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback and Random House audio)

October 16, 2017

Who Said It? (10/16/2017)

President John F. Kennedy, Proclamation 3504 (October 23, 1962), authorizing the naval quarantine of Cuba. This proclamation and a national television address by Kennedy were made in response to the placement of Soviet missiles on the island of Cuba in October 1962. The threat led to the most dangerous Cold War confrontation as the two countries tiptoed toward war. A U.S. spy plane was shot down over Cuba and the prospect of nuclear exchange grew real.

John F. Kennedy, 35th President of the United States (Source: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum)

Any vessel or craft which may be proceeding toward Cuba may be intercepted and may be directed to identify itself, its cargo, equipment and stores and its ports of call, to stop, to lie to, to submit to visit and search, or to proceed as directed. Any vessel or craft which fails or refuses to respond to or comply with directions shall be subject to being taken into custody. Any vessel or craft which it is believed is en route to Cuba and may be carrying prohibited materiel or may itself constitute such materiel shall, wherever possible, be directed to proceed to another destination of its own choice and shall be taken into custody if it fails or refuses to obey such directions. All vessels or craft taken into custody shall be sent into a port of the United States for appropriate disposition.

-President John F. Kennedy

After a period of tense negotiations, the thirteen days marking the most dangerous period of the Cuban missile crisis ended on October 28 when Moscow announced that the Soviet Union had accepted a negotiated solution and affirmed that the missiles would be removed in exchange for a non-invasion pledge from the United States. Other secret agreements included the removal of U.S. missiles that had been placed in Turkey, a NATO ally.

Visit the “The World on the Brink” Cuban Missile Crisis resources a the JFL Presidential Library & Museum.

Pop quiz: What did Washington get when the British surrendered at Yorktown?

Answer: All of the enslaved people in Yorktown who had escaped to the British in hopes of freedom.

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis by John Trumbull (Source: Architect of the U.S. Capitol)

When the British forces under Cornwallis surrendered to George Washington and his French allies on October 19, 1781, the terms of capitulation included the following phrase

It is understood that any property obviously belonging to the inhabitants of these States, in the possession of the garrison, shall be subject to be reclaimed.

(Article IV, Articles of Capitulation; dated October 18, 1781. Source and Complete Text: Avalon Project-Yale Law School)

Thousands of escaped enslaved people had flocked to the British army during Cornwallis’s campaign in Virginia in what has been called the “largest slave rebellion in American history.”

They had come in the belief that the British would free them. Cornwallis had put them to work on the British defense works around the small tobacco port, and when disease started to spread and supplies ran low, Cornwallis forced hundreds of these people out of Yorktown. Many more died from epidemic diseases and the shelling of American and French artillery during the siege.

The African Americans in Yorktown included at least seventeen people who had left Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation with the British, as well as members of Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved community also captured earlier in 1781. They were all returned to bondage, along with thousands of others as Virginian slaveholders came to Yorktown to recover their “property.”

Isaac Granger Jefferson at about age 70 (Courtesy: Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Among them was Isaac Granger Jefferson, a five-year-old boy who was returned to Monticello and later told his story.

The stories of some of the people “reclaimed” by Washington are told in my new book, IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY; The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives.

The Battle of Yorktown and role of African-American soldiers there –as well as the fate of the enslaved people in the besieged town — are featured in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

“A fascinating exploration of war and the myths of war. Kenneth C. Davis shows how interesting the truth can be.” –Evan Thomas, New York Times-bestselling author of Sea of Thunder and John Paul Jones

September 22, 2017

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War

Scheduled for publication in May 2018 by Henry Holt, this book recounts the story of the most deadly epidemic in modern times, the Spanish Flu pandemic, which struck the world 100 years ago during the last months of World War I.

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War -Coming MAY 2018

Publisher’s Description:

Invisible. Incurable. Unstoppable.

From bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis comes a fascinating account of the Spanish influenza pandemic that swept the world from 1918 to 1919.

With 2018 marking the centennial of the worst disease outbreak in modern history, the story of the Spanish flu is more relevant today than ever. This dramatic narrative, told through the stories and voices of the people caught in the deadly maelstrom, explores how this vast, global epidemic was intertwined with the horrors of World War I – and how it could happen again. Complete with photographs, period documents, modern research, and firsthand reports by medical professionals and survivors, this book provides captivating insight into a catastrophe that transformed America in the early twentieth century.

I will be writing more about the book and the subject of the Spanish Flu and the “war to end all wars” as we get closer to publication date. In the meantime, I hope you will also read my previous book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

September 20, 2017

“Mob Rule Cannot Be Allowed”-Little Rock, 1957

“Mob rule cannot be allowed to override the decisions of our courts.”

President Eisenhower (Courtesy: Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum)

President Dwight D. Eisenhower, “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock,” (September 24, 1957)

For a few minutes this evening I want to speak to you about the serious situation that has arisen in Little Rock. To make this talk I have come to the President’s office in the White House. I could have spoken from Rhode Island, where I have been staying recently, but I felt that, in speaking from the house of Lincoln, of Jackson and of Wilson, my words would better convey both the sadness I feel in the action I was compelled today to take and the firmness with which I intend to pursue this course until the orders of the Federal Court at Little Rock can be executed without unlawful interference.

In that city, under the leadership of demagogic extremists, disorderly mobs have deliberately prevented the carrying out of proper orders from a Federal Court. Local authorities have not eliminated that violent opposition and, under the law, I yesterday issued a Proclamation calling upon the mob to disperse.

This morning the mob again gathered in front of the Central High School of Little Rock, obviously for the purpose of again. preventing the carrying out of the Court’s order relating to the admission of Negro children to that school.

Whenever normal agencies prove inadequate to the task and it becomes necessary for the Executive Branch of the Federal Government to use its powers and authority to uphold Federal Courts, the President’s responsibility is inescapable.

In accordance with that responsibility, I have today issued an Executive Order directing the use of troops under Federal authority to aid in the execution of Federal law at Little Rock, Arkansas. This became necessary when my Proclamation of yesterday was not observed, and the obstruction of justice still continues.

Complete text and Source: Dwight D. Eisenhower: “Radio and Television Address to the American People on the Situation in Little Rock.,” September 24, 1957. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

September 19, 2017

A cover is born!

I am very excited to unveil the cover design for my forthcoming book, MORE DEADLY THAN WAR: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War.

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War -Coming MAY 2018

Scheduled for publication in May 2018 by Henry Holt, the book tells the story of the most deadly epidemic in modern times, the Spanish Flu pandemic, which struck the world 100 years ago during the last months of World War I.

The two stories are inseparable. You cannot understand the end of that war without knowing about a global calamity that killed an estimated five percent of the world population in a little more than a year. Spanish Flu killed about as many Americans in one year as have died of HIV/AIDS in thirty years.

This dramatic narrative, told through the stories and voices of the people caught in the deadly maelstrom, explores how this vast, global epidemic was intertwined with the horrors of World War I.

I will be writing more about the book and the subject of the Spanish Flu and the “war to end all wars” as we get closer to publication date. In the meantime, I hope you will also read my previous book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

September 18, 2017

Who Said It? (9/18/2017)

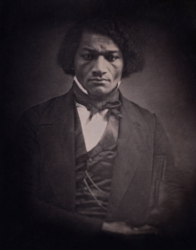

Answer: Frederick Douglass, “Speech to the National Free Soil Convention” (August 11, 1852)

Frederick Douglass circa 1847, age approximately 29 years. Source National Portrait Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Both National Conventions acted in open contempt of the antislavery sentiment of the North, by incorporating, as the corner stone of their two platforms, the infamous law to which I have alluded—a law which, I think, will never be repealed—it is too bad to be repealed—a law fit only to trampled under foot, (suiting the action to the word). The only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter is to make half a dozen or more dead kidnappers. [Laughter and applause.] A half dozen more dead kidnappers carried down South would cool the ardor of Southern gentlemen, and keep their rapacity in check. That is perfectly right as long as the colored man has no protection. The colored men’s rights are less than those of a jackass. No man can take away a jackass without submitting the matter to twelve men in any part of this country. A black man may be carried away without any reference to a jury. It is only necessary to claim him, and that some villain should swear to his identity. There is more protection there for a horse, for a donkey, or anything, rather than a colored man—who is, therefore, justified in the eye of God, in maintaining his right with his arm.

Frederick Douglass: Speech to the National Free Soil Convention August 11, 1852

Source: Frederick Douglass Writing Projects, University of Rochester Libraries

Douglass was talking about the Fugitive Slave Act, enacted on September 18, 1850 as part of the Compromise of 1850. Passage of this law further emboldened abolitionists such as Douglass as well as inspiring Harriet Beecher Stowe to write Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Harriet’s Writing Room Source: Bowdoin College