Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 56

July 27, 2017

“Two Societies, One Black, One White”

(Revised post originally published on February 29, 2016)

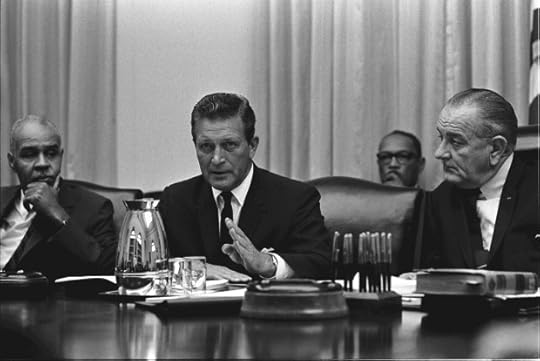

On July 27, 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson established an 11-member National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. He was responding to a series of violent outbursts in predominantly black urban neighborhoods in such cities as Detroit and Newark. (New York Times account.)

Time Magazine cover August 4, 1967

On July 29, 1967, President Johnson made remarks about the reasons for the commission:

The civil peace has been shattered in a number of cities. The American people are deeply disturbed. They are baffled and dismayed by the wholesale looting and violence that has occurred both in small towns and in great metropolitan centers.

No society can tolerate massive violence, any more than a body can tolerate massive disease. And we in America shall not tolerate it.

But just saying that does not solve the problem. We need to know the answers, I think, to three basic questions about these riots:

–What happened?

–Why did it happen?

–What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?

Source:Lyndon B. Johnson: “Remarks Upon Signing Order Establishing the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders.,” July 29, 1967. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

On Feb. 29, 1968, President Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, later known as the Kerner Commission after its chairman, Governor Otto Kerner, Jr. of Illinois, issued a stark warning:

“Our Nation Is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”

Governor of Illinois Otto Kerner, Jr., meeting with Roy Wilkins (left) and President Lyndon Johnson (right) in the White House. 29 July 1967 Source LBJ Presidential Library

The Committee Report went on to identify a set of “deeply held grievances” that it believed had led to the violence.

Although almost all cities had some sort of formal grievance mechanism for handling citizen complaints, this typically was regarded by Negroes as ineffective and was generally ignored.

Although specific grievances varied from city to city, at least 12 deeply held grievances can be identified and ranked into three levels of relative intensity:

First Level of Intensity

1. Police practices

2. Unemployment and underemployment

3. Inadequate housing

Second Level of Intensity

4. Inadequate education

5. Poor recreation facilities and programs

6. Ineffectiveness of the political structure and grievance mechanisms.

Third Level of Intensity

7. Disrespectful white attitudes

8. Discriminatory administration of justice

9. Inadequacy of federal programs

10. Inadequacy of municipal services

11. Discriminatory consumer and credit practices

12. Inadequate welfare programs

Source: “Our Nation is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”: Excerpts from the Kerner Report; American Social History Project / Center for Media and Learning (Graduate Center, CUNY)

and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University).

Issued nearly half a century ago, the list of grievances reads as if it could have been written last week.

July 26, 2017

Don’t Know Much About Executive Order 9981

[Repost; originally posted 7/26/2013]

This is how a president, who actually served in the military (World War I) dealt with discrimination.

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued an Executive Order that ended official discrimination in the United States military.

[image error]

After Truman’s order. the U.S. military was desegregated and integrated units fought in Korea. (Photo: U.S. Army-November 1950)

It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin. This policy shall be put into effect as rapidly as possible, having due regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without impairing efficiency or morale.

Coming in an election year, it was a daring move by Truman, who still needed the support of southern segregationists. It was also a controversial decision that led to the forced retirement of the Secretary of the Army when he refused to desegregate the Army.

As historical documents go, “Executive Order 9981” doesn’t have quite the same ring as “Emancipation Proclamation” or “New Deal.” But when President Harry S. Truman issued this Executive Order, he helped transform the country. This order began the gradual official process of desegregating America’s armed forces, which was a groundbreaking step for the American civil rights movement. (It is worth noting that many of the arguments made at the time against integration of the armed services –unit cohesion, morale of the troops, discipline in the ranks– were also made about the question of homosexuals serving in the military, a policy effectively ended when “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was overturned in 2011.)

In a Defense Department history of the integration of the Armed Forces, Brigadier General James Collins Jr. wrote in 1980:

The integration of the armed forces was a momentous event in our military and national history…. The experiences in World War II and the postwar pressures generated by the civil rights movement compelled all the services –Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps — to reexamine their traditional practices of segregation. While there were differences in the ways that the services moved toward integration, all were subject to the same demands, fears, and prejudices and had the same need to use their resources in a more rational and economical way. All of them reached the same conclusion: traditional attitudes toward minorities must give way to democratic concepts of civil rights.

Here is the text of the Executive Order 9981 (dated July 26, 1948)

A Chronology of events leading to the Order and more information can be found at the the Truman Library.

You can learn more about Truman in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents and more about the Cold War and Korean War in Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

July 15, 2017

Who Said It (July 17, 2017)

President Harry S. Truman, diary entry (July 17, 1945) describing meeting Soviet dictator Josef Stalin at the Potsdam Conference after Germany was defeated in World War II.

Truman had become president when Franklin D. Roosevelt died on April 1945. He met Stalin for the first time on July 17, 1945 at a meeting of the “Big Three” victorious allies in the war against Hitler’s Germany –The Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States.

With the war against Germany over, Truman wanted Stalin’s aid in defeating Japan.

Soviet Prime Minister Josef Stalin, President Harry S. Truman, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill pose for the first time before the opening of the Potsdam Conference. PHOTO SOURCE: National Archies and Records Administration Harry S. Truman Library, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 198797.

“Promptly a few minutes before twelve I looked up from the desk and there stood Stalin in the doorway. I got to my feet and advanced to meet him. He put out his hand and smiled. I did the same. . . . After the usual polite remarks we got down to business. I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument. It pleased him. I asked him if he had the agenda for the meeting. He said he had and that he had some more questions to present. I told him to fire away. He did and it is dynamite—but I have some dynamite too which I’m not exploding now. . . . I can deal with Stalin. He is honest—but smart as hell.”

—From President Truman’s Diary

Source: The National Archives “Eyewitness”

Truman’s “dynamite” was the revelation of the atomic bomb. He told the Soviet dictator about the atomic bomb, unaware that Stalin’s spies had already gotten much of the information about the “Manhattan Project” that developed the bombs later dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945.

This meeting and the events leading up to it are detailed in my book The Hidden History of America At War.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

July 8, 2017

Don’t Know Much About the 14th Amendment

(The original post of this piece is from July 2010 and was revised in 2015 and again in July 2017.)

Image Source: Supreme Court of the United States

On July 9, 1868, the states of Louisiana and South Carolina ratified the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, providing the necessary three-fourths of the states to adopt this very significant Amendment as part of the law of the land.

One of the “Reconstruction Amendments” ratified in the wake of the Civil War, it had far-reaching consequences in American history, touching on every aspect of public and private life in America — from the schoolroom to the bedroom. And it still does.

The first two sections of the Amendment read as follows. The full text of the 14th Amendment can be found at the links to the National Archives and Library of Congress at the bottom of this post.

AMENDMENT XIV Passed by Congress June 13, 1866. Ratified July 9, 1868. Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age,* and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State. *Changed by section 1 of the 26th amendment.

Its immediate impact was to give citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” which included former slaves. Creating national citizenship that was independent of state citizenship, the 14th Amendment reversed the 1857 Dred Scott decision which denied citizenship to most slaves.

Think of a controversial court decision in our history and chances are the 14th Amendment is involved. It has been invoked in such major decisions as Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which ended segregation of public schools; Roe v. Wade (1973), which disallowed most existing restrictions on abortion; and Loving v. Virginia (1967), which ended race-based restrictions on marriage in America. It also provided the Constitutional authority for many of the most important pieces of civil rights legislation passed in the 1960s. And the 14th Amendment has been central to the same-sex marriage debate. Here is an article from the National Constitution Center on 10 Supreme Court Cases about the 14th Amendment.

And here are other resources on the 14th Amendment from the National Constitution Center’s Interactive Constitution.

In addition, the 14th Amendment forbids states from denying any person “life, liberty or property, without due process of law” or to “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of its laws.”

These clauses, usually referred to as “due process” and “equal protection,” have been involved in some of the most significant decisions in American history. You don’t need to be a Constitutional scholar to understand this Amendment and the profound impact it has had –and continues to have– on every American’s life.

Here is a link to the National Archives US Constitution site

Here is a link to more information on the 14th Amendment from the Library of Congress

July 1, 2017

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (11 of 11)

The Declaration Mural by Barry Faukner (National Archives)

Last part of a series on the lives of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. (A YES following the entry means the signer enslaved people; a NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

A New England slaver. A forgotten founder who died in debt and disgrace. A college president. A legendary bullet maker. Jefferson’s teacher –and a murder victim. Last but not least among the 56 signers.

–William Whipple (New Hampshire) Usually described as a 46 year old merchant, he was more precisely a sea captain who made a fortune sailing between Africa and the West Indies — in other words, the slave trade. He also enslaved people and one of those men, known as Prince, accompanied Whipple throughout his illustrious career as an officer in the Revolution. It was thought that Prince was the black man depicted in the famous “Washington Crossing the Delaware” painting, but that is not accurate because Prince and Whipple were far from the action that night. Whipple later served in a variety of state offices in New Hampshire and legally manumitted Prince –who also went by the name of Caleb Quotum — in 1784. Whipple died in Portsmouth in 1785. YES

–William Williams (Connecticut) A 45 year old merchant, he was a veteran of the French and Indian War who had married the daughter of Connecticut’s Royal Governor. He was not present for the July vote but signed the Declaration and was a tireless supporter of the war effort. After a long career in public service, he died in 1811, aged 71. NO

–James Wilson (Pennsylvania) Scottish born, he was a 33 year old lawyer at the time of the signing and one of the most important Founding Fathers you probably never heard of. A key supporter of the Declaration, Wilson was among the signers and Philadelphia elites who were attacked in his home during the war in a riot over food prices and scarcity. Wilson was also a key member of the Constitutional Convention, credited with several significant compromises. Although hopeful to be made Chief Justice of the new Supreme Court, he was appointed an associate by Washington. But land speculation ruined him and he ended up in debtor’s prison, like his colleague Robert Morris (See previous post #7) before his death in disgrace at age 55 in 1798, an embarrassment to his Federalists friends and colleagues. NO

–John Witherspoon (New Jersey) Another profoundly influential immigrant, the Scottish born minister was 53 year old president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) where his hatred of the British influenced many students including notable schoolmates Aaron Burr and James Madison. He lost a son at the battle of Germantown in 1777 but continued his career in Congress. After the war, he attempted to rebuild the college and was a prime mover in the growth and organization of the Presbyterian Church. He died in 1794 in Princeton, where the is buried, at age 71. YES

–Oliver Wolcott (Connecticut) A 49 year old lawyer, he was a veteran of the French and Indian War who was not present for the vote and signed at a later date. Wolcott was in New York when Washington’s troops tore down a statue of King George III after hearing the Declaration of Independence read. He is credited with the plan to melt down the lead statue and turn it into bullets for the war effort. He served in the Connecticut militia during the Revolution and held a series of state posts after the war including as governor of Connecticut at his death in 1797 , aged 71. YES

–George Wythe (Virginia) A 50 year old lawyer, he made his greatest mark as a teacher of law to Thomas Jefferson at the College of William and Mary –as well as later students including James Monroe, future Chief Justice John Marshall and congressman Henry Clay, earning him the title “America’s first law professor.” He died in 1806 , around 80, apparently murdered by a nephew who was perturbed that Wythe was planning to free the slaves that the young man was supposed to inherit. (The nephew was acquitted of murder but convicted of forging his uncle’s checks). YES

Read the story of James Wilson and the Philadelphia Riot in America’s Hidden History.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

June 30, 2017

Whatever Became of 56 Signers (Part 10 of 11)

(Part 10 of a series that begins here. A YES at the end of the entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

A victim of the British. Two Irish immigrants. An orphaned carpenter. Among the next five of 56 signers.

–Richard Stockton (New Jersey) Of the signers who clearly suffered for his actions, this successful and widely-admired 45 year old attorney at the signing, may have suffered most. Stockton is also credited with recruiting John Witherspoon, an influential Sottish minister, (See next installment in series) to become president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton). Betrayed by loyalists in his home state, he was captured by the British in 1776, although later released in a prisoner exchange, not for having sworn allegiance to the King, as reported in a much-disputed rumor of the day. His New Jersey home was also damaged by the British but later restored. Stockton was in poor health after the experience in captivity but lived until 1781, when he died of throat cancer. YES

–Thomas Stone (Maryland) Among the conservatives in Congress, he was a 33 year old attorney at the signing, reluctant about independence, but then joining in the favorable vote. Another son of a wealthy planter, he had a low profile after the signing, helping write the Articles of Confederation but not signing them. He also declined to take part in the Constitutional Convention, when his wife, who fell ill following an inoculation against smallpox, died in 1787. Apparently despondent, he died four months later in 1787 at age 44. YES

–George Taylor (Pennsylvania) Arriving in America as an indentured servant from Ireland, he was a 60 year old merchant and iron maker at the signing. He had risen at the foundry where he worked to become bookkeeper, then bought the business after his employer’s death and then married the late owner’s widow. Taylor was not in the influential Pennsylvania delegation for the July vote, but signed the document in August. During the war, his foundry provided cannon and cannonballs for the war effort, but Congress was notoriously slow to pay its bills and his business suffered. He died in 1781 at age 65. YES

–Matthew Thornton (New Hampshire) An Irish-born physician, he was around 62 at the signing, a veteran surgeon who had served with the New Hampshire militia in the French and Indian War. A latecomer to Congress, he joined in November 1776 and was later permitted to add his name to the document. He later served as a state judge and then operated a farm and ferry before his death in 1803 at about age 89. NO

–George Walton (Georgia) Orphaned and apprenticed as a carpenter, he was a 35 year old self taught attorney at the signing. Although his exact birth date is unknown, some claim that he was the youngest Signer – a distinction usually given to Edward Rutledge (See previous entry). Serving with the Georgia militia, he was shot and captured by the British in 1778. Well-treated, he was held for a year before being exchanged for a British officer –even though it was known he was a signer. He later served in a variety of state offices, including governor and senator from Georgia, and built a home on lands confiscated after the war from a Tory, or Loyalist. He is implicated in the events that led to the duel that killed fellow signer and political rival Button Gwinnet (see Part 3 of series). He died in 1804, aged 63 (?) . Yes/No? [Unable to confirm his status as slaveholder pending further investigation.]

. Yes/No? [Unable to confirm his status as slaveholder pending further investigation.]

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

June 29, 2017

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (Part 9)

(Part 9 in a series that begins here; a YES following the entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

Betsy Ross’s uncle. The “first psychiatrist.” Youngest signer. The Great Compromiser. An Irish man named Smith. The next five signers:

–George Ross (Pennsylvania) The son of a Scottish-born minister, he was a 46 year old attorney at the signing, a loyalist before turning to the patriot cause in 1775. Yes, he was Betsy’s uncle, but the rest of the Ross flag story has been dismissed as family legend. He left Congress in early 1777 due to illness — the same severe gout that afflicted a number of signers– and served as a Pennsylvania judge before his death in 1779 at 49, following a severe attack of gout. NO

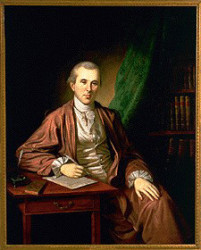

Dr Benjamin Rush by Charles Willson Peale c. 1783. Winterthur Museum

–Benjamin Rush (Pennsylvania) Raised by a widowed mother, he was a 30 year old physician at the signing, youngest in the Pennsylvania delegation. He was elected after the July vote and his diaries, letters and notes provided some of the best portraits of many of the signers and other founders. He served as surgeon general of the armies during the war, and became an early abolitionist while still a slaveholder himself. Rush was an early advocate of many modern medical practices, while at the same time practicing bloodletting. He established the first free medical clinic and remained in Philadelphia during a yellow fever epidemic, spoke against capital punishment and for the idea that there was mental illness which led to his being called “The Father of American Psychiatry.” He died of typhus in 1813 at age 67. YES

–Edward Rutledge (South Carolina) Son of an Irish immigrant physician, he was a 26 year old attorney at the signing, the youngest of the signers. Rutledge later left Congress and was captured by the British when Charleston fell in May 1780 and was held for nearly a year. After the war, his finances and businesses flourished and he returned to state politics, and was elected governor of South Carolina, but died at 50 in 1800, before his term ended. YES

–Roger Sherman (Connecticut) A self-educated son of a farmer, he was a prosperous merchant, attorney and politician, aged 55 at the signing. He would sign three of the central documents in America’s foundation: the Declaration (he was a member of the draft committee), the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution. It was at the 1787 convention that Sherman proposed the “Great Compromise” that ended the deadlock between large and small states. He was also a true “Founding Father”–after Carroll (18 children) and Ellery (16 children), Sherman fathered the third most children among the signers -15. A leading Federalist, he served in the House and Senate, where he was serving at his death in 1793 at age 72. NO

–James Smith (Pennsylvania) Another immigrant signer, he was born in Ireland and was around 57 at the signing, another self-taught attorney. Elected to Congress after the July vote, he signed the Declaration. He returned to law practice and state offices before his death in 1806 at about age 87. NO

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

June 28, 2017

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (Part 8)

[Part 8 of a blog series that begins here. Note: YES following an entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.]

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

Minister turned lawyer. Self-taught planters’s sons. A Nay vote. A rare bachelor. And a veiled man. The next six signers:

–Thomas Nelson, Jr. (Virginia) Another son of a wealthy planter. he was a 37 year old merchant-planter at the signing, owner of more than 400 enslaved people. He raised money to supply troops and even commanded militia. Legend has it that he fired a cannon at his own Yorktown mansion during the 1781 siege when told that it was British headquarters. The war cost him financially and he was in ill health, retiring as Virginia’s governor and living on his plantation until his death at 50 in 1789. YES

–William Paca (Maryland) An attorney and wealthy planter’s son, he was 35 at the signing. A patriot leader in somewhat conservative Maryland, he helped bring the state to favor independence at Philadelphia. He raised funds for the war effort and later, as Congressman, worked to support veterans. An advocate of the Constitution, he was later appointed a federal judge by President Washington, and was in that post at his death in 1799 at age 58. YES

Robert Treat Paine (Courtesy: Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts)

–Robert Treat Paine (Massachusetts) Overshadowed by two Adamses and Hancock from Massachusetts, he was a minister turned attorney, 45 at the signing, best known as one of the prosecutors in the 1770 trial of the British soldiers charged in “Boston Massacre.” His friend and fellow delegate John Adams had served rather successfully as their defender. In 1780, he was among the founders of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the first American groups dedicated to expanding scientific knowledge and learning. After the war, he remained active in Massachusetts politics and was named a state judge by Hancock until his retirement in 1804 due to deafness. He died in 1814 at age 83. NO

–John Penn (North Carolina) A wealthy planter’s son who taught himself to read and write, he was a 36 year old attorney at the signing. He remained in Congress and was one of the signers who also signed the first American constitution, the Articles of Confederation. He retired to private law practice and died in 1788 at age 48. YES

–George Read ( Delaware) Among the conservative delegates, he was a 42 year old lawyer at the time of the signing but had voted against independence on July 2.He served in state offices until ill health forced his resignation. But he returned to Philadelphia to take part in the Constitutional convention and was leading voice for small states’s rights and led the ratification forces in Delaware, the first state to ratify the Constitution. Elected to the Senate, he resigned to take a judgeship in Delaware before his death in 1798 at age 65. YES

–Caesar Rodney (Delaware) Another self educated attorney, son of a planter, he was 47 at the signing. He is best known for an 80 mile ride in a storm to break a deadlock that put Delaware in the independence column –which cost him favor with conservatives in his home state. One of the three bachelor signers (Francis Lee and Thomas Lynch were the others), he remained in the Congress until he became Delaware’s state president. A cancerous growth on his face was untreated and he covered it with a silk veil, worn for a decade before his death in 1784 at age 55. YES

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

June 27, 2017

Whatever Became of 56 Signers (7th in series)

(Part 7 in a series that begins here. NOTE: YES following the entry means the Signer enslaved people; No means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

A tavern owner’s son. Two of America’s wealthiest men –both named Morris. And the first to die. The next five signers in this series;

-Thomas McKean (Delaware) Son of a Pennsylvania farmer-tavern owner, McKean was a self educated, 42 year old attorney turned politician at the time of the signing (although he did not sign in 1776). A vigorous patriot, he held offices in both his native Pennsylvania and Delaware and was a key supporter of the Declaration. When another delegate from Delaware was absent and the state might vote against independence, McKean sent a horse and rider to collect fellow delegate Caesar Rodney and bring him back to vote —an 80 mile ride in a storm. There is some dispute about when he actually signed but it was after January 1777. McKean and his family were pursued by the British but never captured. A vocal advocate of the Constitution, he served in many state posts, including governor of Pennsylvania, and prospered after the war. He died in 1817 at age 83. YES

–Arthur Middleton (South Carolina) A 34 year old plantation owner, at the signing, replaced his father –thought too conservative — in Congress. Educated in England, he became active in patriot politics.One of the few deletes to serve in the wartime militia, he was captured in Charleston in 1780, along with Thomas Heyward (Post #4) and Rutledge, two other South Carolina signers. Although his home had been destroyed he was released by the British and returned to Congress in 1781. After the war he returned to his plantation where he died at age 44 in 1787. YES

–Lewis Morris (New York) Another of the wealthy sons of prominent New York families in the state’s delegation, Morris was a 50 year old land owner with large holdings in what is now the Bronx in New York City. Although his home was assaulted by British troops during the war, it was attacked and severely damaged because of its value, not because he was a signer. Morris led troops of the militia during the vote in July, but then led the New York delegation in later signing the Declaration, making it unanimous. Morris rebuilt the family home and land holdings after the war and was a leader with Alexander Hamilton in ratification of the Constitution. He died in 1798, aged 71 and his former plantation is known today as the Morrisania section of the Bronx. YES

Oil painting of Robert Morris by Robert Pine (c. 1785)

–Robert Morris (Pennsylvania) (No relation to Lewis Morris above.) One of the wealthiest individuals in America, he was a 42 year old Philadelphia merchant and speculator when he signed. Born in Liverpool, he had come to America and made a fortune as a merchant, becoming the “Financier of the Revolution.” Accused of profiteering during the war, he was attacked in the Philadelphia home of fellow signer James Wilson. A delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, he declined to serve as Washington’s secretary of Treasury, recommending Alexander Hamilton instead. He later became a Senator. But he lost his fortune through land speculation and was bankrupted and put in debtor’s prison. He died in poverty and relative obscurity in 1806, aged 72. YES

–John Morton (Pennsylvania) A farm boy turned surveyor, he was 52 at the time of the signing. He has two key distinctions: his vote pushed Pennsylvania into the pro-independence camp and then he was first signer to die. He fell ill in 1777 and died at about age 52, leaving his farm and enslaved people to his wife and children who had to flee from a British attack. YES

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

June 26, 2017

Don’t Know Much About® the Korean War

(Update of 2010 post)

It used to be called the “Forgotten War.”

But it is no longer forgotten, as recent headlines out of North Korea prove. And it never really ended.

The Korean War started on June 25, 1950. More than one hundred thousand troops from Communist-ruled North Korea invaded South Korea.

In the wake of World War II, when Korea had been brutally occupied by the Japanese, the Korean peninsula was divided by the victorious allies between a Soviet-allied North and a western allied South Korea.

The UN called the invasion a violation of international peace and demanded that the Communists withdraw. In what was called a UN “police action,” sixteen UN countries sent troops to help the South Koreans, and 41 countries sent military equipment and other supplies. But the United States provided about 90 percent of the troops, military equipment, and supplies.

Fighting in the Korean War, one of the bloodiest wars in history, ended on July 27, 1953, when the UN and North Korea signed an armistice. A permanent peace treaty between South Korea and North Korea has never been signed. What else do you know about this Cold War conflict that had the world on brink of World War III? (Answers below)

1. Who first commanded the UN troops in Korea?

2. What nation entered the war on North Korea’s side?

3. What two aviation “firsts” occurred during the war?

4. Why did President Truman fire General MacArthur?

5. What were American losses in the Korean war?

Although it attracts less attention than the nearby Vietnam War Memorial, there is a Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C. A National Parks Service link: http://www.nps.gov/kwvm/

In the Korean War, the U.S. military was integrated. (Source: Library of Congress)

The Korean War also marked the first time in American history that the armed services were integrated, following Truman’s Executive Order desegregating the military in 1948. Read more about that order here.

You can read about Korea and the Cold War era in Don’t Know Much About History and The Hidden History of America at War.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

Answers

1. On July 8, with the approval of the UN Security Council, Pres. Truman named Douglas MacArthur commander in chief of the United Nations Command.

2. More than 300,000 Communist Chinese troops crossed into North Korea in October 1950 and U.S. and Chinese troops first clashed on October 25. They fought until November 6, when the Chinese suddenly withdrew.

3. The Korean war marked the first battles between jet aircraft and for the first time, helicopters carried troops into combat.

4. One of the controversies of the war occurred in April 1951, when President Truman removed General MacArthur from command, the result of a continuing dispute between MacArthur and defense leaders in Washington. MacArthur wanted to bomb bases in a part of China, and use other “all-out measures.” Truman feared such actions might lead to a third world war. The decision was very unpopular; MacArthur was viewed as a hero and Truman’s popularity plunged. It was one of the reasons he chose not to run for another term. World War II hero General Dwight Eisenhower, the Republican candidate, won election as President in 1952 on a stunning vow to end the war.

5. The Department of Defense reports that 54,246 Americans service men and women lost their lives during the Korean War. This includes all losses worldwide during that period. As there has been no peace treaty, those Americans who lost their lives in the Demilitarized Zone of Korea since the Armistice are also included.