Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 58

June 11, 2017

Don’t Know Much About the Lovings-50 Years Later

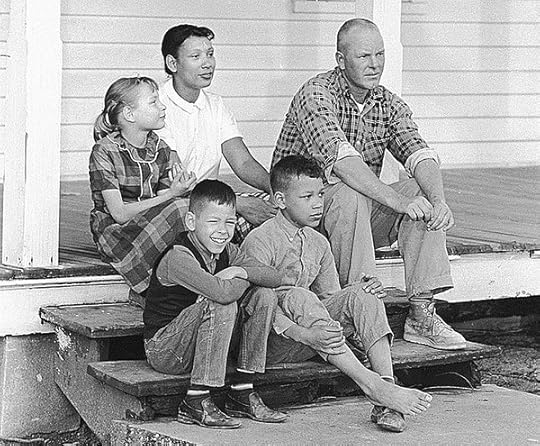

Richard and Mildred Loving at their home in Central Point, Va. with their children, Peggy (from left), Donald and Sidney, in 1967. Free Lance-Star, via Associated Press

[2017 Revision of an earlier post]

When the the Supreme Court made its historic ruling in two cases in 2015 related to marriage equality (“Highlights from the Supreme Court Decisions on Same-Sex Marriage,” New York Times), the decision drew upon the case of Loving v. Virginia —decided by the Supreme Court on June 12, 1967 –50 years ago.

The case involved the law in Virginia, and other states, which prohibited interracial marriage, or “miscegenation.”

Loving v. Virginia changed that. And America.

“Today, one in six newlyweds in the United States has a spouse of a different race or ethnicity, according to a recent analysis of 2015 census data by the Pew Research Center. That is a five-fold increase from 1967, when just 3 percent of marriages crossed ethnic and racial lines.” (Source: New York Times)

Richard Loving, a white man, married Mildred, a 18-year-old woman of African-American and Native American descent, in Washington, D.C. When they returned to their native Virginia, they were arrested in the middle of the night and the Lovings were forced to leave Virginia. A few years later, young Mildred asked Robert F. Kennedy, the new Attorney General, for help. He suggested the American Civil Liberties Union and she wrote to them. Two young lawyers decided to take the case. They brought suit which eventually found its way to the Supreme Court

The Court ruled that anti-miscegenation laws, such as those in Virginia, violated the Due Process Clause (“No person shall be … deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law….” ) and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment (“nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law …”).

In the unanimous majority opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote:

“Marriage is one of the ‘basic civil rights of man,’ fundamental to our very existence and survival.”

Change in American history is often slow. And it usually comes from the bottom up –not the top down. Whether it was abolition, civil rights, or even independence itself, when it comes to most of the great social upheavals of our past, the politicians and “leaders” have generally had to be dragged kicking and screaming in the direction of change. It may be glacially slow, but it will happen, in part because there is a generational change that made same sex marriage prohibitions on the books seem as antiquated –and as wrong —as the now-unconstitutional bans on interracial marriage.

Before her death in 2008, Mildred Loving, the young woman who brought the suit against Virginia, issued a statement on the 40th anniversary of the decision. She wrote:

“Surrounded as I am now by wonderful children and grandchildren, not a day goes by that I don’t think of Richard and our love, our right to marry, and how much it meant to me to have that freedom to marry the person precious to me, even if others thought he was the ‘wrong kind of person’ for me to marry. I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people’s religious beliefs over others. I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving, and loving, are all about.”

The January/February 2012 issue of Humanities magazine featured the Lovings as did a recent HBO documentary, The Loving Story.

There is a more complete discussion of the history of the Lovings, their case and its connection to the same sex marriage debate in the new, revised edition of Don’t Know Much About History: Anniversary Edition.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

June 7, 2017

Don’t Know Much About® Homer Plessy

[Revision of post from 2012]

What did “separate but equal” mean?

On this date 125 years ago — June 7, 1892– Homer Plessy was arrested when he refused to leave an all-whites railroad car in New Orleans. It was no accident. A 30-year-old shoemaker born to parents who were classed as “free people of color,” Plessy had been chosen to deliberately violate the law so that it could be challenged in court.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

Homer Plessy was seven-eighths Caucasian and one-eighth black, an “octaroon” in the parlance of the day, and in facial features, he appeared to be Caucasian. But when he tried to sit in a railroad coach reserved for whites, that one-eighth was all that counted. Plessy was arrested, in accordance with an 1890 Louisiana law separating railroad coaches by race. Assisted by the Comité des Citoyens (“Citizens’ Committee”), a pioneering civil rights group, Plessy fought his arrest all the way to the Supreme Court in 1896.

Unfortunately, this was the same Supreme Court that had protected corporations as “persons” under the Fourteenth Amendment, ruled that companies controlling 98 percent of the sugar business weren’t monopolies, and jailed striking workers who were “restraining trade.”

In Plessy’s case, the arch-conservative, business-minded Court showed it was also racist in a decision that was every bit as indecent and unfair as the Dred Scott decision before the Civil War. The majority decision in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson established a new judicial idea in America—the concept of “separate but equal,” meaning states could legally segregate races in public accommodations, such as railroad cars and public schools. In his majority opinion, delivered on May 18, 1896, Justice Henry Brown wrote,

We consider the underlying fallacy of the plaintiff’s argument to consist in the assumption that the enforced separation of the two races stamps the colored race with a badge of inferiority. If this be so, it is not by reason of anything found in the act, but solely because the colored race chooses to put that construction upon it.

The problem with this fine notion, of course, was that every facet of life in the South was increasingly separate —schools, dining areas, trains and later buses, drinking fountains, and lunch counters— but they were never equal.

The lone dissenter in this case was John Marshall Harlan (1833–1911) of Kentucky. In his eloquent dissent, Harlan wrote,

“The arbitrary separation of citizens, on the basis of race, while they are on a public highway, is a badge of servitude wholly inconsistent with the civil freedom and the equality before the law established by the Constitution. It cannot be justified upon any legal grounds. . . . We boast of the freedom enjoyed by our people above all other peoples. But it is difficult to reconcile that boast with a state of the law which, practically, puts the brand of servitude and degradation upon a large class of our fellow-citizens, our equals before the law.”

In practical terms, Plessy v. Ferguson had given the Court’s institutional stamp of approval to segregation and generations of “Jim Crow” laws. It would be another sixty years before another Supreme Court decision overturned the “separate but equal” doctrine in Brown v Board of Education.

A transcript of the Plessy ruling can be found in the “100 Milestone Documents” site of the National Archives.

This entry is adapted from the revised and updated Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

June 5, 2017

Who Said It? (6/5/17)

John Adams, writing as “Novanglus,” Boston Gazette [1774] no. 7. Incorporated in Article 30 of the Declaration of Rights in the Massachusetts Constitution [1780].

“A government of laws, and not of men.”

Source: The John Adams Historical Society website

John Adams, Second POTUS , official portrit (Source: White House Historical Association)

According to Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations:

“Adams credits this formulation to James Harrington [1611-1677], with those work The Commonwealth of Oceana [1656] he was familiar, Adams’s use of the phrase gave it wide circulation in America.” (p. 337)

A few years earlier, Adams had written notes for a speech he gave in the spring of 1772. He wrote:

There is danger from all men. The only maxim of a free government ought to be to trust no man living with power to endanger the public liberty.” [Bartlett’s p. 337; John Adams Historical Society]

May 30, 2017

Who Said It (5/29/2017)

John F. Kennedy –“Remarks at Amherst College upon receiving an Honorary Degree,” October 26, 1963, Public Papers of the Presidents: John F. Kennedy, 1963.

President John F. Kennedy (1961)

“We must never forget that art is not a form of propaganda; it is a form of truth.”

Source: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

May 29, 2017

Don’t Know Much About® JFK

President John F. Kennedy (1961)

(Photo by Alfred Eisenstadt-Courtesy of White House Press Office)

[Earlier post revised 5/29/2017]

Frozen in time as the youthful avatar of a new generation in American politics, John F. Kennedy would have been 100 years old yesterday. He was born on May 29, 1917.

Now, more than 50 years after John F. Kennedy was inaugurated, the public remains fascinated with the man, his family, and his times. His life and loves, his controversial death, and the legacy of his brief presidency and extended family continue to exert a hold on the American imagination.

When JFK was assassinated on November 22, 1963, the modern myth-making machine was set in motion. It transformed a president who had committed serious mistakes while also conjuring brilliant successes into a sun- dappled, all-American legend— a modern young King Arthur from Camelot, the popular musical of the day, which became the enduring image of his abbreviated life and presidency.

Elected at forty-two—still the youngest elected president— and dead at forty-six, John F. Kennedy had, in the lyrics of Camelot, a “brief, shining moment” that remains one of the most extraordinary passages in American history, shaping the course of modern presidential politics and history. From the Bay of Pigs fiasco to the near-disaster of the Cuban Missile Crisis and America’s growing involvement in Vietnam, all set against the American civil rights crusade, the glow of Kennedy’s legacy as president has been dulled by time. Yet he remains beloved by many Americans.

✱ Kennedy was the first president born in the twentieth century.

✱ He was the first, and to date, only Roman Catholic to be elected president.

✱ To date, Kennedy is the only president to win a Pulitzer Prize, for Profiles in Courage. Before his death in 2008, former Kennedy speechwriter Theodore Sorensen confirmed that he had written the book with Kennedy.

✱ Kennedy was the first president to have a poet take part in his inaugural. Robert Frost recited from memory an older poem, “The Gift Outright,”

✱ While there had been gardens at the White House since the time of John Adams, and presidents such as Jefferson and John Quincy Adams had been enthusiastic gardeners, the iconic “Rose Garden,” outside the president’s office, was formalized by Kennedy. After his 1961 trip to Europe, Kennedy wanted a more formal setting for official use.

✱ John F. Kennedy and William Taft are the only presidents buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Following his death, this obituary appeared in the New York Times.

The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum is in Boston.

You can read more about John F. Kennedy and his presidency in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About® History

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

May 23, 2017

Who Said It? (5/23/17)

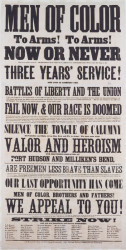

John Logan “Memorial Day Order” (May 5, 1868)

General Logan, a Civil War veteran, was the leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, a powerful fraternal organization of Union veterans. The order he issued calling for a day to mark the graves of those who had died in the fight to preserve the Union and end slavery became the basis for Decoration Day, later called Memorial Day. Read a complete history of the holiday here: “The Divisive and Partisan History of Memorial Day”

We are organized, comrades, as our regulations tell us, for the purpose, among other things, “of preserving and strengthening those kind and fraternal feelings which have bound together the soldiers, sailors and marines who united to suppress the late rebellion.” What can aid more to assure this result than by cherishing tenderly the memory of our heroic dead who made their breasts a barricade between our country and its foes? Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains and their deaths the tattoo of rebellious tyranny in arms. We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds. Let pleasant paths invite the coming and going of reverent visitors and fond mourners. Let no vandalism of avarice or neglect, no ravages of time, testify to the present or to the coming generations that we have forgotten, as a people, the cost of a free and undivided republic.

Source and Complete Text: National Cemetery Administration

Read more about Memorial Day, the Civil War, and the history of slavery in these books:

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

May 22, 2017

The Divisive & Partisan History of “Memorial Day”

(Revise of 2015 post)

It is a well-established fact that Americans like to argue. And we do. Mays or Mantle. A Caddy or a Lincoln. And, of course, abolition, abortion, and guns.

But a debate over Memorial Day –and more specifically where and how it began? America’s most solemn holiday should be free of rancor. But it never has been.

The heated arguments over removing the Confederate flag and monuments to heroes and soldiers of the Confederacy in New Orleans and provide examples and reminders of the birth of Memorial Day.

Born out of the Civil War’s catastrophic death toll as “Decoration Day,” Memorial Day is a day for honoring our nation’s war dead.

Waterloo, New York claimed that the holiday originated there with a parade and decoration of the graves of fallen soldiers in 1866. But according to the Veterans Administration, at least 25 places stake a claim to the birth of Memorial Day. Among the pack are Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, which says it was first in 1864.( “Many Claim to Be Memorial Day Birthplace” )

And Charleston, South Carolina, according to historian David Blight, points to a parade of emancipated children in May 1865 who decorated the graves of fallen Union soldiers whose remains were moved from a racetrack to a proper cemetery.

But the passions cut deeper than pride of place.

From its inception, Decoration Day (later Memorial Day) was linked to “Yankee” losses in the cause of emancipation.

Calling for the first formal Decoration Day, Union General John Logan wrote, “Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains…”

Leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, Logan set the first somber commemoration on May 30, 1868, in Arlington Cemetery, the sacred space wrested from property once belonging to Robert E. Lee’s family.( When Memorial Day was No Picnic by James M. McPherson.)

In other words, Logan’s first Decoration Day was divisive— a partisan affair, organized by northerners.

In 1871, Frederick Douglass gave a Memorial Day speech in Arlington that focused on this division:

We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.

I am no minister of malice. I would not strike the fallen. I would not repel the repentant; but may my “right hand forget her cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth,” if I forget the difference between the parties to that terrible, protracted, and bloody conflict.

But the question remains: what inspired Logan to call for this rite of decorating soldier’s graves with fresh flowers?

The simple answer is—his wife.

While visiting Petersburg, Virginia – which fell to General Grant 150 years ago in 1865 after a year-long, deadly siege – Mary Logan learned about the city’s women who had formed a Ladies’ Memorial Association. Their aim was to show admiration “…for those who died defending homes and loved ones.”

Choosing June 9th, the anniversary of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” in 1864, a teacher had taken her students to the city’s cemetery to decorate the graves of the fallen. General Logan’s wife wrote to him about the practice. Soon after, he ordered a day of remembrance.

The teacher and her students, it is worth noting, had placed flowers and flags on both Union and Confederate graves.

As America wages its partisan wars at full pitch, this may be a lesson for us all.

More resources at the New York Times Topics archive of Memorial Day articles

The story of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” is told in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR (Now in paperback)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

May 15, 2017

Who Said It (5/15/17)

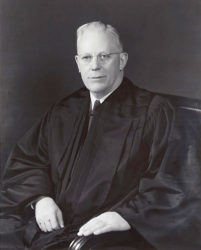

Chief Justice Earl Warren, Opinion of the Court Brown v Board of Education of Topeka (May 17, 1954)

This unanimous decision ruled that racial segregation of public schools is unconstitutional, overturning the “separate but equal” doctrine established in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896. The decision stated that

“separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Undated photo of Earl Warren, 14th Chief Justice of the United States

“In the instant cases … there are findings below that the Negro and white schools involved have been equalized, or are being equalized, with respect to buildings, curricula, qualifications and salaries of teachers, and other “tangible” factors. Our decision, therefore, cannot turn on merely a comparison of these tangible factors in the Negro and white schools involved in each of the cases. We must look instead to the effect of segregation itself on public education.

In approaching this problem, we cannot turn the clock back to 1868, when the Amendment was adopted, or even to 1896, when Plessy v. Ferguson was written. We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.”

Source and Excerpts of decisions on Brown v Board of Education cases. Teaching American History

May 12, 2017

Mother’s Day-A “Hidden History”

[Updated post]

Let me be among the first to say Happy Mother’s Day. Spouses, partners, and children everywhere: Don’t forget.

But amidst the brunches, flower-giving, and chocolate samplers, there is a story of another “Mother’s Day” that is worth remembering this weekend.

Julia Ward Howe, a prominent abolitionist best known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” published what became known as the “Mother’s Day Proclamation,” originally called “An Appeal to Womanhood Throughout the World.”

Julia Ward Howe (1907) Source: Library of Congress

In 1870, Howe wrote:

Our husbands shall not come to us reeking with carnage, for caresses and applause. Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy, and patience. . . . From the bosom of the devastated earth a voice goes up with our own. It says, Disarm, Disarm! The sword of murder is not the balance of justice! Blood does not wipe out dishonor nor violence indicate possession.

Source and Complete Text: Library of Congress

Howe’s international call for mothers to become the voice of pacifism found few takers. Even among like-minded women, there was greater urgency over the suffrage question. Her passionate campaign for a “Mother’s Day for Peace” begun in 1872 fell by the wayside.

Mother’s Day, as we know it, is not the invention of Hallmark; it started in 1912 through the efforts of West Virginia’s Anna Jarvis to create a holiday honoring all mothers for their sacrifice and to assist mothers who needed help.

Today, Mother’s Day is largely a commercial bonanza — flowers, chocolates and greeting cards. Is it possible to truly honor Howe’s version of Mother’s Day and work towards her original vision of Mother’s Day?

If only we remember the history behind the holiday and what she thought it should be.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

May 8, 2017

Who Said It? (5/8/2017)

President Harry S. Truman May 8, 1945 V-E Day

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

THE PRESIDENT. Well, I want to start off by reading you a little statement here. I want you to understand, at the very beginning, that this press conference is held with the understanding that any and all information given you here is for release at 9 a.m. this morning, eastern war time. There should be no indication of the news given here, or speculation about it, either in the press or on the radio before 9 o’clock this morning.

The radio-my radio remarks, and telegrams of congratulation to the Allied military leaders, are for release at the same time. Mr. Daniels has copies of my remarks, available for you in the lobby as you go out, and also one or two releases here.

[1.] Now, for your benefit, because you won’t get a chance to listen over the radio, I am going to read you the proclamation, and the principal remarks. It won’t take but 7 minutes, so you needn’t be uneasy. You have plenty of time. [Laughter]

“This is a solemn but glorious hour. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly all over Europe.”

Source: Harry S. Truman: “The President’s News Conference on V-E Day,” May 8, 1945. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

Harry S. Truman was born on May 8. Read more about him in this post, Don’t Know Much About® Harry Truman