Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 57

June 26, 2017

Who Said It? (6/26/2017)

President Harry S. Truman “Statement on the Situation in Korea” (June 27, 1950)

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

“IN KOREA the Government forces, which were armed to prevent border raids and to preserve internal security, were attacked by invading forces from North Korea. The Security Council of the United Nations called upon the invading troops to cease hostilities and to withdraw to the 38th parallel. This they have not done, but on the contrary have pressed the attack. The Security Council called upon all members of the United Nations to render every assistance to the United Nations in the execution of this resolution. In these circumstances I have ordered United States air and sea forces to give the Korean Government troops cover and support.”

Source and Full Text: “Statement by the President on the Situation in Korea” June 27, 1950. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

On June 25, 2017, war broke out on the Korean Peninsula as forces from the communist North invaded South Korea. Forces from the United States were soon committed to the fighting, although there was no declaration of war by Congress.

With her brother on her back a war weary Korean girl tiredly trudges by a stalled M-26 tank, at Haengju, Korea., 06/09/1951 Item from Record Group 80: General Records of the Department of the Navy Resources on the Korean War from the National Archives.

June 25, 2017

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (6th in a series)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

(Sixth in a series. The first post is here.)

Wealthy planters, merchants and moderates

-Richard Henry Lee (Virginia) A 41 year old planter from a prominent Virginia family –his younger brother Francis Lightfoot (See previous post) was also there– Lee deserves more acclaim than he usually gets. A “great orator,” said John Adams, Lee introduced the resolution for independence. Curiously he left Congress and didn’t vote for the resolution or the Declaration, which he signed later in the summer of 1776. He was one of the few signers to actually serve with a Virginia militia unit. He remained in poetics after the war, becoming a vocal opponent of the Constitution but an advocate for the Bill of Rights. He was elected to the U.S. Senate but resigned in ill health and died at age 62 in 1794. YES

–Francis Lewis (New York) A native of Wales, he was a 63 year old merchant at the time of the signing, a key supporter of George Washington, but was instructed not to vote for the Declaration by New York. He then signed in August. During the war, his wife was imprisoned by the British and died shortly after her release, leaving Lewis grief-stricken. He died in 1802 at age 89, was buried in an unmarked grave at Manhattan’s Trinity Church, and now, curious New Yorkers will know why there is a Francis Lewis Boulevard in Queens. YES

–Philip Livingston (New York) The 60-year-old member of one of New York’s wealthiest families, he was a merchant who favored the patriot cause but was, like many New Yorkers, more moderate about declaring independence and was absent when the entire delegation abstained from the vote. But he signed in August. (Robert Livingston, a cousin and member of the Declaration draft committee, was also absent from the vote and never signed the Declaration). The British occupied his Brooklyn home after the fall of New York and used it as a hospital. Although he sold some of his property to support the war effort, his family continued to amass large land holdings in upstate New York. In poor health, he died at age 62 in 1778, when Congress was forced to evacuate Philadelphia and moved to York, Pa. YES

–Thomas Lynch, Jr. (South Carolina) At 27, the second youngest signer (after Edward Rutledge also of South Carolina), he was lawyer and son of a delegate. When his father, a wealthy planter, suffered a stroke, the younger Lynch was sent to Congress. (His father was unable to vote or sign.) Both left for home in poor health and the elder Lynch died en route. Lynch Jr. and his wife later sailed for France in the hope of regaining his health but both died at sea in 1779. YES

June 24, 2017

Whatever Became of 56 Signers (5th in a series)

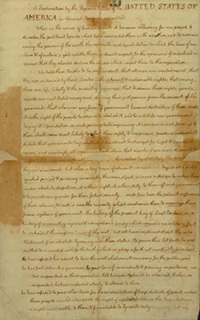

Fair Copy of the Draft of the Declaration of Independence (Source New York Public Library)

(This is the fifth in a series. The first post is linked here.)

Slave trader turned early abolitionist. Flag designer. “First President.” And the Author.

-Stephen Hopkins (Rhode Island) Second oldest delegate after Franklin, Hopkins was 69 years old at the signing. A merchant, he had been Rhode Island’s colonial governor but was an outspoken advocate of independence. A partner of the wealthy Brown brothers who were involved in the slave trade –Newport was a key northern slavery port– he enslaved several people. But in 1774, he secured passage of law prohibiting the slave trade in Rhode Island, one of the first anti-slavery laws in the colonies and he began freeing some but not all of the people he enslaved. In ill health, he retired from politics and public life and died in 1785 at age 78. YES, but he had begun began freeing some of them by 1776.

-Francis Hopkinson (New Jersey) Like Franklin and Jefferson, Hopkinson was a man of many talents, a 38 year old attorney and musician at the time of the signing, he was the son of the founder –with Franklin– of the University of Pennsylvania and was among the school’s first graduates. Though long overlooked, he has more recently gotten his due as the designer of the “Stars and Stripes.” The claim is based on Hopkinson submitting a bill for his work on the flag and requesting “a quarter cask of the public wine” in payment. He was already on the Congressional payroll so was refused. While his home was ransacked during the war, he emerged relatively unscathed and later became a Federal judge before his death in 1791 at 53. YES

-Samuel Huntington (Connecticut) An apprenticed barrel-maker who became a successful attorney, he was a 45 year old politician at the time of the signing, having resigned his post as “King’s Attorney.” His true distinction is serving as “President of the United States in Congress Assembled” when the Articles of Confederation were adopted –making him the “First President,” sort of. Others have staked that claim as well. He served in a variety of national and state posts, including being the sitting governor of Connecticut at his death in 1796 at age 64. NO

–Thomas Jefferson (Virginia) 33 year old planter, scientist, writer, lawyer. You know most of the rest. But Jefferson’s wartime service as Virginia’s governor is sometimes overlooked. In 1781,he was governor when the British attacked the state, including forces led by Benedict Arnold. Jefferson fled and was later investigated by the state legislature but no charges were filed. Some of his slaves were taken by the British and were being held in Yorktown during the siege in September-October 1781 and were later returned to Jefferson by George Washington. He died, like John Adams, on the 50th anniversary of the adoption–July 4, 1826. See the Monticello site for more information. YES

–Francis Lightfoot Lee (Virginia) A member of the state’s prominent planter family, he was 41 years old at the signing, the quiet brother of Richard Henry Lee, who offered the first resolution calling for independence in June 1776. After the war, he was a prominent advocate of the new Constitution, unlike his more visible older brother. He left the national scene and died at age 62 in 1797. YES

June 23, 2017

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (4th in a series)

Fair Copy of the Draft of the Declaration of Independence (Source New York Public Library)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Part 4 in a series that begins here.

Father and grandfather of presidents. A simple farmer. A workaholic. The next five signers, in alphabetical order: (Yes following the entry means slaveholder; No means not a slaveholder.)

-Benjamin Harrison (Virginia) A member of the Virginia aristocracy, he was a well-to-do planter, around 50 at the the signing. Although his famed Berkeley Plantation on the James River was supposedly destroyed during the Revolution, it clearly survived. So did Harrison, who went on to serve three terms as governor of Virginia before his death in 1791 at age 65. Besides his role in the July 2 and 4 votes in Philadelphia, he is mostly distinctive as the father of 9th president William Henry Harrison and grandfather of namesake Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd president. YES

-John Hart (New Jersey) Described as a well-meaning “Jersey” farmer with little education, Hart was a 65 year old planter at the time of the signing, and devoted to the patriot cause. Although supposedly hounded by the British during the war, he was later able to entertain General Washington and allow 12,000 troops to camp in his fields in 1778. He died of kidney stones in 1779, aged 68. YES

–Joseph Hewes (North Carolina) Born in New Jersey, he moved to North Carolina and was a 46 year old Quaker merchant at the signing. At first a reluctant patriot, he broke with the Quakers over the possibility of a violent rebellion and was considered a key influence in Congress by John Adams. His shipping experience was significant enough for him to be described as the first “secretary of the Navy,” responsible for getting his friend John Paul Jones a commission. Working relentlessly for the Congress, Hewes fell sick and died in 1779 at age 49 and was deeply mourned by his Congressional colleagues. YES

-Thomas Heyward, Jr. (South Carolina) Son of a wealthy planter, he was a 30 year old lawyer at the signing. Heyward counts as one of the few signers actually captured by the British, who then took his enslaved people, apparently shipping them to bondage in the West Indies. Initially paroled (released under an agreement), he was later taken aboard a prison ship and then held in St. Augustine, Florida under a form of house arrest until released in a prisoner exchange. While a hostage, he is credited with writing verses to a song called “God Save the Thirteen States.” He dabbled in politics after the war, but focused on rebuilding his family plantation where he died at 63 in 1809. YES

-William Hooper (North Carolina) Born in Boston, he was a 34 year old attorney who had moved South at the signing. He missed the key July vote but returned to sign the Declaration in August. Hooper was one of the signers who suffered losses during the war when the British invaders evacuating the Wilmington, North Carolina area and destroyed his home. He later pressed for ratification of the Constitution but lacked popularity in his adopted state and, suffering from a variety of illnesses, including malaria, died in 1790 at age 48. YES

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

June 22, 2017

Whatever Became Of…56 Signers? (3d in series)

Fair Copy of the Draft of the Declaration of Independence (Source New York Public Library)

[Post revised June 22,2017]

Part 3 in a series of posts about the fates of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. A printer, a politician with a notable name, a duelist, a Connecticut Yankee, and the most famous signature in U.S. history.

A Yes after their names means they enslaved people; No means they did not.

-Benjamin Franklin (Pennsylvania) America’s most famous man in 1776, Franklin was 70 years old at the time of the signing. Printer, publisher, writer, scientist, diplomat, philosopher –he was the embodiment of the Enlightenment ideal. A member of the draft committee that produced the Declaration, Franklin was a central figure in the independence vote and then helped the war effort by winning crucial French support for the America cause. But he lost no Fortune, reportedly tripling his wealth during the conflict. Franklin returned to the scene of the Declaration’s passage in 1787 to help draft the Constitution.. When he died at age 84 in 1790, his funeral was attended by a crowd equal to Philadelphia’s population at the time. Read more on Franklin at this National Park Service site. YES

–Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts) A 32 year old merchant from Marblehead, Gerry (pronounced with a hard G like Gary) is much more famous for later dividing Massachusetts into oddly-shaped voting districts as the state’s governor. A cartoonist compared the districts to a salamander and the word “gerry-mandering” was born. Though he voted for independence, Gerry was not present to sign in August, signing later in the fall of 1776, He profited from the war and later joined the Massachusetts delegation to the Constitutional convention in 1787, although he refused to sign the Constitution. He became James Madison’s second vice president in 1813, but died in office in 1814 at age 70. NO

–Button Gwinnett (Georgia) An English-born plantation owner and merchant, he was 41 at the time of the signing. And didn’t last much longer. A political argument with a Georgia general led to a duel in which Gwinnett was mortally wounded. He died in 1777 at age 42, the second of the signers to die. (John Morton of Pennsylvania was first.) YES

–Lyman Hall ( Georgia) A Connecticut Yankee physician transplanted to Georgia plantation owner, Hall was 52 years old at the signing. A vocal patriot when Georgia was far more hesitant about independence, he first came to Philadelphia as a nonvoting delegate. Hall’s plantation was destroyed during the war when the British made their punishing attacks on the South. He later served as Georgia’s governor, dying at age 66 in 1790. YES

–John Hancock (Massachusetts) Born into a poor parson’s family in Lexington (National Parks Service site) , Hancock was sent to live with a wealthy uncle when his father died. He inherited his uncle’s shipping business and was one of America’s wealthiest men by the time he was thirty. A patriot leader in Boston, it was Hancock and Samuel Adams who the British sought to capture on that April 1775 night when the war began. President of the Continental Congress when independence was declared, he was 39 at the time of the signing. The outsized signature on the document cemented his fame in American lore. After the war, Hancock was governor of Massachusetts at the time of his death in 1793 at age 56. YES

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

June 21, 2017

Whatever Became Of…56 Signers? (2d in a series)

Fair Copy of the Draft of the Declaration of Independence (Source New York Public Library)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Part 2 of a series that begins here. (A YES denotes slaveowner or trader; NO means the person did not enslave people.)

Here are the next five Signers of the Declaration, continuing in alphabetical order:

–Samuel Chase (Maryland) A 35 year old attorney, Chase has the distinction of being among those signers who didn’t vote on July 4; he signed the later printed version in August. Accused of wartime profiteering but never tried or convicted, he later went broke from business speculating and settled into law practice. President George Washington appointed him to the Supreme Court, and Chase became the first justice to be impeached –although he was acquitted. He died in 1811 at age 70. YES Learn more about Impeachment history here.

-Abraham Clark (New Jersey) An attorney, 50 years old at the signing, Clark had two sons who were captured and imprisoned during the war; one on the notorious British prison ship Jersey and the other in a New York jail cell. Clark served in Congress on and off and opposed the Constitution’s ratification until the Bill of Rights was added. He died in 1794 at age 68. YES

–George Clymer (Pennsylvania) A 37 year old merchant the time of the signing, Clymer was a well-heeled patriot leader who helped fund the American war effort. He was also elected to Congress after the July 2 independence vote, signing the Declaration on August 2. He belongs to an elite group who signed both the Declaration and the Constitution. (The others were Roger Sherman of Conn,; George Read of Del.; and Franklin, Robert Morris and James Wilson, all of PA.) He continued to prosper after the war and died in 1813 at age 74. NO

-William Ellery (Rhode Island) A modestly successful merchant turned attorney, aged 48 at the signing, Ellery replaced an earlier Rhode Island delegate who died of smallpox in Philadelphia. (Smallpox killed more Americans than the war did during the Revolution.) A dedicated member of Congress during the war years, Ellery saw his home burned by the British although it is thought unlikely they knew it was the home of a Signer. An abolitionist, he was rewarded after the war by President Washington with the lucrative post of collector for the port of Newport which he held for three decades. He died in 1829, aged 92, second in longevity among signers after Carroll. (See previous post.) NO

-William Floyd (New York) A 41 year old land speculator born on Long Island, New York, Floyd abstained from the July 2 independence vote with the rest of the New York delegation, but is thought to be the first New Yorker to sign the Declaration on August 2. Reports that his home on Fire Island was destroyed by the British were exaggerated, although it was used as a stable and barracks by the occupying Redcoats. (It is now part of a Fire Island National Park.) Floyd served in the first Congress before moving to western New York where he owned massive land tracts and where he died at age 86 in 1821. YES

Read more about the Revolution, Declaration and “Forgotten Founders” in these books:

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

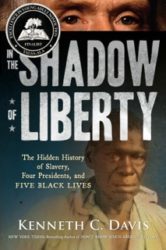

And In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives

June 20, 2017

“Lives, Fortunes, Sacred Honor:” Whatever Became Of 56 Signers? (1 in a series)

They pledged:

“... our Lives, our Fortunes, and our Sacred Honor.”

Then what happened?

The Grand Flag of the Union, the “first American flag,” originally raised in 1775 and later by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

This is an updated repost (June 2017) of a series about the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence. Included in this list is a simple guide to those Signers who enslaved people. A Yes means they enslaved people; a No means they did not.

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Those strong words concluded the Declaration of Independence when it was adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776.

There is little question that men who signed that document were putting their lives at risk. The identity and fates of a handful of those Signers is well-known. Two future presidents — Adams and Jefferson— and America’s most famous man, Benjamin Franklin, were on the Committee that drafted the document.

But the names and fortunes of many of the other signers, including the most visible, John Hancock, are more obscure. In the days leading up to Independence Day, I will offer a thumbnail sketch of each of the Signers in alphabetical order. Some prospered and thrived; some did not: How many of those Signers actually paid with their Lives, Fortunes, and Sacred Honor?

–John Adams (Massachusetts) Aged 40 when he signed, he went on to become the first vice president and second president of the United States. Adams died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration in 1826 at age 90. (Jefferson died that same day) NO

–Samuel Adams (Mass.) Older cousin to John, Samuel Adams was 53 at the signing. He went on to a career in state politics, initially refused to sign the Constitution because it lacked a Bill of Rights, and was governor of Massachusetts. He died in 1803 at 81. NO

–Josiah Bartlett (New Hampshire) Inspiring the name of the fictional president of West Wing fame on TV, Bartlett was a physician, aged 46 at the time of the signing. He helped ratify the Constitution in his home state, giving the document the necessary nine states to become the law of the land. Elected senator he chose to remain in New Hampshire as governor. Three of his sons and other descendants also became physicians. He died in 1795 at age 65. YES

–Carter Braxton (Virginia) A 39-year-old plantation owner, Braxton was looking to invest in the slave trade before the Revolution. Initially reluctant about independence, he helped fund the rebellion and lost a considerable fortune during the war –not because he was a signer, but because of shipping losses during the war itself. He later served in the Virginia legislature and died in 1797 at age 61, far less wealthy than he had been, but also far from impoverished. YES

–Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Maryland) A plantation owner, 38 years old and one of America’s wealthiest men at the signing, Carroll was the only Roman Catholic signer and the last signer to die. With hundreds of enslaved people on his properties, Carroll considered freeing some of them before his death and later introduced a bill for gradual abolition in Maryland, which had no chance of passage. At age ninety-one, he laid the cornerstone of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as a member of its board of directors. He died in 1832 at age 95. YES

Update: Carroll’s cousin was John Carroll, a Jesuit priest, first Roman Catholic bishop in the United States, and a founder of Georgetown College. The New York Times has reported how, in 1838, Georgetown sold 272 enslaved people to keep the college financially afloat.

And read more about the Declaration and the Signers in:

DON’T KNOW MUCH ABOUT® THE AMERICAN PRESIDENTS (Hachette Paperback/Random House Audio)

Don’t Know Much ABout® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial/Random House Audio)

June 15, 2017

“Juneteenth is for Everyone”

Monday June 19, 2017 is a day to mark “Juneteenth” –a holiday celebrating emancipation at the end of the Civil War.

Foods on the Juneteenth altar include beets, strawberries, watermelon, yams and hibiscus tea, as well as a plate of black-eyed peas and cornbread. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York Times

“SOME two months after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, effectively ending the Civil War, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger steamed into the port of Galveston, Tex. With 1,800 Union soldiers, including a contingent of United States Colored Troops, Granger was there to establish martial law over the westernmost state in the defeated Confederacy.

On June 19, two days after his arrival and 150 years ago today, Granger stood on the balcony of a building in downtown Galveston and read General Order No. 3 to the assembled crowd below. “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free,” he pronounced.” (New York Times June 19, 2015)

Read the complete history of Juneteenth in my New York Times Op-ed, “Juneteenth is for Everyone”. The celebration of the the holiday and its traditions of foods is highlighted in this New York Times article, “Hot Links and Red Drinks”

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

June 14, 2017

Juneteenth- Time to celebrate

The official Juneteenth Committee in East Woods Park, Austin, Texas on June 19, 1900. (Courtesy Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

[Repost of 2014 post]

Happy Juneteenth! Since 1865, June 19th has served as another kind of Independence Day. It is a day that celebrates the end of slavery in America.

On June 19, 1865, Union General Gordon Granger informed former slaves in the area from the Gulf of Mexico to Galveston, Texas that they were free. Abraham Lincoln had officially issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, but it had taken two more years of Union victories to end the war in April 1865 and for this news to reach enslaved people in remote sections of the country.

This is from General Granger’s Order No. 3:

The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor. The freedmen are advised to remain quietly at their present homes and work for wages. They are informed that they will not be allowed to collect at military posts and that they will not be supported in idleness either there or elsewhere.

Many of the newly freed slaves in the territory, the last area to receive news of the war’s end and Emancipation, celebrated the news with ecstasy, and according to the Texas State Library, the words “June” and “nineteenth” became a new word and a new celebration of freedom. They called it Juneteenth.

In many parts of Texas, ex-slaves purchased land, or “emancipation grounds,” for the Juneteenth gathering. Examples include: Emancipation Park in Houston, purchased in 1872; what is now Booker T. Washington Park in Mexia; and Emancipation park in East Austin.

Other former slaves began to travel to other states in search of family members who had been separated from them by slave sales. Starting in 1866, that spontaneous celebration –more commonly called “Juneteenth”– spread to become a holiday celebrating emancipation in many parts of the United States, although it still lacks national recognition. Read more about Juneteenth in the article Juneteenth: Our Other Independence Day , which I wrote for Smithsonian.com

June 13, 2017

Don’t Know Much About Impeachment?

“An impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history.”

–House Minority Leader Gerald Ford (April 1970)

In the summer of 1787, as the framers debated the Constitution, Benjamin Franklin worried about how to get ride of corrupt or incompetent officials. Without some method of removal, the only recourse was assassination.

The other delegates agreed. And after considerable debate, they added the power of impeachment to the list of checks and balances of the legislature on the other two branches.

Read the history of impeachment in this article from Smithsonian, “The History of American Impeachment.”

Read more about the Constitutional power of impeachment in these articles from the National Constitution Center.