Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 51

June 21, 2018

Whatever Became Of…56 Signers? (2d in a series)

Fair Copy of the Draft of the Declaration of Independence (Source New York Public Library)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Part 2 of a series that begins here. (A YES denotes slaveowner or trader; NO means the person did not enslave people.)

Here are the next five Signers of the Declaration, continuing in alphabetical order:

–Samuel Chase (Maryland) A 35 year old attorney, Chase has the distinction of being among those signers who didn’t vote on July 4; he signed the later printed version in August. Accused of wartime profiteering but never tried or convicted, he later went broke from business speculating and settled into law practice. President George Washington appointed him to the Supreme Court, and Chase became the first justice to be impeached –although he was acquitted. He died in 1811 at age 70. YES Learn more about Impeachment history here.

-Abraham Clark (New Jersey) An attorney, 50 years old at the signing, Clark had two sons who were captured and imprisoned during the war; one on the notorious British prison ship Jersey and the other in a New York jail cell. Clark served in Congress on and off and opposed the Constitution’s ratification until the Bill of Rights was added. He died in 1794 at age 68. YES

–George Clymer (Pennsylvania) A 37 year old merchant the time of the signing, Clymer was a well-heeled patriot leader who helped fund the American war effort. He was also elected to Congress after the July 2 independence vote, signing the Declaration on August 2. He belongs to an elite group who signed both the Declaration and the Constitution. (The others were Roger Sherman of Conn,; George Read of Del.; and Franklin, Robert Morris and James Wilson, all of PA.) He continued to prosper after the war and died in 1813 at age 74. NO

-William Ellery (Rhode Island) A modestly successful merchant turned attorney, aged 48 at the signing, Ellery replaced an earlier Rhode Island delegate who died of smallpox in Philadelphia. (Smallpox killed more Americans than the war did during the Revolution.) A dedicated member of Congress during the war years, Ellery saw his home burned by the British although it is thought unlikely they knew it was the home of a Signer. An abolitionist, he was rewarded after the war by President Washington with the lucrative post of collector for the port of Newport which he held for three decades. He died in 1829, aged 92, second in longevity among signers after Carroll. (See previous post.) NO

-William Floyd (New York) A 41 year old land speculator born on Long Island, New York, Floyd abstained from the July 2 independence vote with the rest of the New York delegation, but is thought to be the first New Yorker to sign the Declaration on August 2. Reports that his home on Fire Island was destroyed by the British were exaggerated, although it was used as a stable and barracks by the occupying Redcoats. (It is now part of a Fire Island National Park.) Floyd served in the first Congress before moving to western New York where he owned massive land tracts and where he died at age 86 in 1821. YES

Read more about the Revolution, Declaration and “Forgotten Founders.”

In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives

June 20, 2018

“Lives, Fortunes, Sacred Honor:” Whatever Became Of 56 Signers? (1 in a series)

They pledged:

“... our Lives, our Fortunes, and our Sacred Honor.”

Then what happened?

The Grand Flag of the Union, the “first American flag,” originally raised in 1775 and later by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

This is an updated repost of a series about the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence. Included in this list is a simple guide to those Signers who enslaved people. A Yes means they enslaved people; a No means they did not.

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Those strong words concluded the Declaration of Independence when it was adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776.

There is little question that men who signed that document were putting their lives at risk. The identity and fates of a handful of those Signers is well-known. Two future presidents — Adams and Jefferson— and America’s most famous man, Benjamin Franklin, were on the Committee that drafted the document.

But the names and fortunes of many of the other signers, including the most visible, John Hancock, are more obscure. In the days leading up to Independence Day, I will offer a thumbnail sketch of each of the Signers in alphabetical order. Some prospered and thrived; some did not: How many of those Signers actually paid with their Lives, Fortunes, and Sacred Honor?

–John Adams (Massachusetts) Aged 40 when he signed, he went on to become the first vice president and second president of the United States. Adams died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration in 1826 at age 90. (Jefferson died that same day) NO

–Samuel Adams (Mass.) Older cousin to John, Samuel Adams was 53 at the signing. He went on to a career in state politics, initially refused to sign the Constitution because it lacked a Bill of Rights, and was governor of Massachusetts. He died in 1803 at 81. NO

–Josiah Bartlett (New Hampshire) Inspiring the name of the fictional president of West Wing fame on TV, Bartlett was a physician, aged 46 at the time of the signing. He helped ratify the Constitution in his home state, giving the document the necessary nine states to become the law of the land. Elected senator he chose to remain in New Hampshire as governor. Three of his sons and other descendants also became physicians. He died in 1795 at age 65. YES

–Carter Braxton (Virginia) A 39-year-old plantation owner, Braxton was looking to invest in the slave trade before the Revolution. Initially reluctant about independence, he helped fund the rebellion and lost a considerable fortune during the war –not because he was a signer, but because of shipping losses during the war itself. He later served in the Virginia legislature and died in 1797 at age 61, far less wealthy than he had been, but also far from impoverished. YES

–Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Maryland) A plantation owner, 38 years old and one of America’s wealthiest men at the signing, Carroll was the only Roman Catholic signer and the last signer to die. With hundreds of enslaved people on his properties, Carroll considered freeing some of them before his death and later introduced a bill for gradual abolition in Maryland, which had no chance of passage. At age ninety-one, he laid the cornerstone of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as a member of its board of directors. He died in 1832 at age 95. YES

Update: Carroll’s cousin was John Carroll, a Jesuit priest, first Roman Catholic bishop in the United States, and a founder of Georgetown College. The New York Times has reported how, in 1838, Georgetown sold 272 enslaved people to keep the college financially afloat.

June 19, 2018

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War (Available May 15)

Now available, this book recounts the story of the most deadly epidemic in modern times, the Spanish Flu pandemic, which struck the world 100 years ago during the last months of World War I.

The book and audio versions are available for preorder and links to online sellers can be found here.

Davis (In the Shadow of Liberty) immediately sets the urgent tone of his forthright chronicle, citing staggering statistics: the Spanish Flu pandemic that began in spring 1918 claimed the lives of more than 675,000 Americans in a single year and left a worldwide death toll estimated at 100 million. The author structures his exhaustive account of the origins, transmission, and consequences of the pandemic within the framework of WWI, underscoring the lethal concurrence of these “twin catastrophes.”

Invisible. Incurable. Unstoppable.

From bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis comes a fascinating account of the Spanish influenza pandemic that swept the world from 1918 to 1919.

With 2018 marking the centennial of the worst disease outbreak in modern history, the story of the Spanish flu is more relevant today than ever. This dramatic narrative, told through the stories and voices of the people caught in the deadly maelstrom, explores how this vast, global epidemic was intertwined with the horrors of World War I – and how it could happen again. Complete with photographs, period documents, modern research, and firsthand reports by medical professionals and survivors, this book provides captivating insight into a catastrophe that transformed America in the early twentieth century.

Listen to a sample of the Audio version coming from Penguin Random House Audio.

I hope you will also read my previous book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

June 12, 2018

Juneteenth: The “Other” Independence Day

(Revised of a post from June 2015)

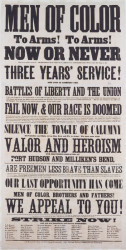

TUESDAY JUNE 19 is a day to mark “Juneteenth” –a holiday celebrating emancipation at the end of the Civil War.

Foods on the Juneteenth altar include beets, strawberries, watermelon, yams and hibiscus tea, as well as a plate of black-eyed peas and cornbread. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York Times

“For centuries, slavery was the dark stain on America’s soul, the deep contradiction to the nation’s founding ideals of “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and “All men are created equal.” When Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, he took a huge step toward erasing that stain. But the full force of his proclamation would not be realized until June 19, 1865—Juneteenth, as it was called by slaves in Texas freed that day.”

“Juneteenth: Our Other Independence Day” My article in Smithsonian (June 15, 2011)

“SOME two months after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, effectively ending the Civil War, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger steamed into the port of Galveston, Tex. With 1,800 Union soldiers, including a contingent of United States Colored Troops, Granger was there to establish martial law over the westernmost state in the defeated Confederacy.

On June 19, two days after his arrival and 150 years ago today, Granger stood on the balcony of a building in downtown Galveston and read General Order No. 3 to the assembled crowd below. “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free,” he pronounced.” (New York Times June 19, 2015)

Read more of the complete story of Juneteenth in my New York Times Op-ed, “Juneteenth is for Everyone”. The celebration of the the holiday and its traditions of foods is highlighted in this New York Times article, “Hot Links and Red Drinks”

May 21, 2018

Don’t Know Much About® Memorial Day

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= (This video was originally posted May 2012. It was produced, edited and directed by Colin Davis.)

Memorial Day brings thoughts of duty, honor, courage, sacrifice and loss. The holiday, the most somber date on the American national calendar, was born in the ashes of the Civil War as “Decoration Day,” when General John S. Logan –a-veteran of the Mexican and Civil Wars, a prominent Illinois politician and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union fraternal organization –called for May 30, 1868 as the day on which the graves of fallen Union soldiers would be decorated with fresh flowers.

“We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the Nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds.”

Pointedly, Logan’s order was seen as a day to honor those who died in the cause if ending slavery and opposing the “rebellion.”

Every year at this time, I spend a lot of time talking about the roots and traditions of Memorial Day.

It’s not about the barbecue or the Mattress Sales. Obscured by the holiday atmosphere around Memorial Day is the fact that it is the most solemn day on the national calendar. This video tells a bit about the history behind the holiday.

One way to mark Memorial Day is by simply reading the Gettysburg Address. Here is a link to the Library of Congress and its page on the Address. I also discussed Memorial Day in a previous post.

Soldiers of the 146th Infantry, 37th Division, crossing the Scheldt River at Nederzwalm under fire. Image courtesy of The National Archives.

One of the most famous symbols of the loss on Memorial Day is the Poppy, inspired by this World War I poem by John McCrae, “In Flanders Fields”

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place, and in the sky,

The larks, still bravely singing, fly,

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead; short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe!

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high!

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Source: The poem is in the public domain courtesy of Poets.org

Have a memorable Memorial Day!

(Images in video:Courtesy of the Library of Congress and Flanders Cemetery image Courtesy of the American Battle Monuments Commission)

May 20, 2018

150 Years of the Divisive & Partisan History of “Memorial Day”

MEMORIAL DAY -MONDAY MAY 28, 2018

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Photo: Arlington National Cemetery) This memorial was created after the great losses of World War I.

(Revise of 2015 post)

It is a well-established fact that Americans like to argue. And we do. Mays or Mantle. A Caddy or a Lincoln. And, of course, abolition, abortion, and guns.

But a debate over Memorial Day –and more specifically where and how it began? America’s most solemn holiday should be free of rancor. But it never has been.

The heated arguments over removing the Confederate flag and monuments to heroes and soldiers of the Confederacy in New Orleans and provide examples and reminders of the birth of Memorial Day.

In the Korean War, the U.S. military was integrated. (Source: Library of Congress)

Waterloo, New York claimed that the holiday originated there with a parade and decoration of the graves of fallen soldiers in 1866. But according to the Veterans Administration, at least 25 places stake a claim to the birth of Memorial Day. Among the pack are Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, which says it was first in 1864.( “Many Claim to Be Memorial Day Birthplace” )

And Charleston, South Carolina, according to historian David Blight, points to a parade of emancipated children in May 1865 who decorated the graves of fallen Union soldiers whose remains were moved from a racetrack to a proper cemetery.

But the passions cut deeper than pride of place.

Born 150 years ago out of the Civil War’s catastrophic death toll as “Decoration Day,” Memorial Day is a day for honoring our nation’s war dead. A veteran of the Mexican War and the Civil War, John A. Logan, a Congressman and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, set the first somber commemoration on May 30, 1868, in Arlington Cemetery, the sacred space wrested from property once belonging to Robert E. Lee’s family.( When Memorial Day was No Picnic by James M. McPherson.) The Grand Army of the Republic was a powerful fraternal organization formed of Civil War Union veterans.

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

From its inception, Decoration Day (later Memorial Day) was linked to “Yankee” losses in the cause of emancipation. Calling for the first formal Decoration Day, Union General John Logan wrote, “Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains…”

In other words, Logan’s first Decoration Day was divisive— a partisan affair, organized by northerners.

In 1871, Frederick Douglass gave a Memorial Day speech in Arlington that focused on this division:

We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.

I am no minister of malice. I would not strike the fallen. I would not repel the repentant; but may my “right hand forget her cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth,” if I forget the difference between the parties to that terrible, protracted, and bloody conflict.

But the question remains: what inspired Logan to call for this rite of decorating soldier’s graves with fresh flowers?

The simple answer is—his wife.

While visiting Petersburg, Virginia – which fell to General Grant 150 years ago in 1865 after a year-long, deadly siege – Mary Logan learned about the city’s women who had formed a Ladies’ Memorial Association. Their aim was to show admiration “…for those who died defending homes and loved ones.”

Choosing June 9th, the anniversary of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” in 1864, a teacher had taken her students to the city’s cemetery to decorate the graves of the fallen. General Logan’s wife wrote to him about the practice. Soon after, he ordered a day of remembrance.

The teacher and her students, it is worth noting, had placed flowers and flags on both Union and Confederate graves.

As America wages its partisan wars at full pitch, this may be a lesson for us all.

More resources at the New York Times Topics archive of Memorial Day articles

The story of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” is told in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR (Now in paperback)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

May 18, 2018

Who Said It? (5/19/2014)

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964)

(Photo: Arnold Newman, WHite House Press Office)

President Lyndon B. Johnson, “The Great Society” Speech (University of Michigan, May 22. 1964)

Each year more than 100,000 high school graduates with proved ability do not enter college because they cannot afford it. And if we cannot educate today’s youth, what will we do in 1970 when elementary school enrollment will be five million greater than 1960? And high school enrollment will rise by five million. And college enrollment will increase by more than three million.

In many places, classrooms are overcrowded and curricula are outdated. Most of our qualified teachers are underpaid, and many of our paid teachers are unqualified. So we must give every child a place to sit and a teacher to learn from. Poverty must not be a bar to learning, and learning must offer an escape from poverty.

But more classrooms and more teachers are not enough. We must seek an educational system which grows in excellence as it grows in size. And this means better training for our teachers. It means preparing youth to enjoy their hours of leisure, as well as their hours of labor. It means exploring new techniques of teaching, to find new ways to stimulate the love of learning and the capacity for creation.

Source: American Experience-PBS: “LBJ”

A few months after declaring a “War on Poverty,” President Lyndon B. Johnson outlined his ambitious domestic agenda to end poverty, improve the status of African Americans and create a more equal and just American society. In the speech Johnson said,

The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time. But that is just the beginning.

The range of programs that were introduced fifty years ago included Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, Head Start, and the Job Corps.

In April 2014, New York Times reporter Trip Gabriel assessed the War on Poverty half a century later in “Fifty Years Into the War on Poverty, Hardship Hits Back.”

President Johnson was a schoolteacher in a poor, rural district in Texas before entering politics. Read more about his life, administration and legacy in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About History,

May 14, 2018

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War (Available May 15)

Available on May 15, 2018 by Henry Holt, this book recounts the story of the most deadly epidemic in modern times, the Spanish Flu pandemic, which struck the world 100 years ago during the last months of World War I.

The book and audio versions are available for preorder and links to online sellers can be found here.

Davis (In the Shadow of Liberty) immediately sets the urgent tone of his forthright chronicle, citing staggering statistics: the Spanish Flu pandemic that began in spring 1918 claimed the lives of more than 675,000 Americans in a single year and left a worldwide death toll estimated at 100 million. The author structures his exhaustive account of the origins, transmission, and consequences of the pandemic within the framework of WWI, underscoring the lethal concurrence of these “twin catastrophes.”

Invisible. Incurable. Unstoppable.

From bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis comes a fascinating account of the Spanish influenza pandemic that swept the world from 1918 to 1919.

With 2018 marking the centennial of the worst disease outbreak in modern history, the story of the Spanish flu is more relevant today than ever. This dramatic narrative, told through the stories and voices of the people caught in the deadly maelstrom, explores how this vast, global epidemic was intertwined with the horrors of World War I – and how it could happen again. Complete with photographs, period documents, modern research, and firsthand reports by medical professionals and survivors, this book provides captivating insight into a catastrophe that transformed America in the early twentieth century.

Listen to a sample of the Audio version coming from Penguin Random House Audio.

I hope you will also read my previous book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

May 13, 2018

In the Shadow of Liberty

As the headlines show almost daily, the history of slavery and its role in American history and society has never been more important –or more misunderstood. My recent book puts a human face on slavery and its significance in American history through the lives of five remarkable people who were enslaved some of America’s most famous men.

In The Shadow Of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives

•Notable Children’s Books-2017 ALSC/ALA

•A FINALIST for 2017 Award for Excellence in Young Adult Nonfiction by YALSA — the Young Adult Library Services Association of the American Library Association.

•A selection of the 2018 Tayshas Reading List/Texas Library Association

•Named one of the BEST CHILDREN’S AND YOUNG ADULT BOOKS OF 2016 (Washington Post)

LINKS TO PURCHASE THE BOOK AND AUDIO CAN BE FOUND HERE

Did you know that many of America’s Founding Fathers—who fought for liberty and justice for all—were slave owners?

Through the powerful stories of five enslaved people who were “owned” by four of our greatest presidents, this book helps set the record straight about the role slavery played in the founding of America. These dramatic narratives explore our country’s great tragedy—that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

BILLY LEE, who became George Washington’s valet and fought in the American Revolution alongside him.

ONA JUDGE, who escaped from Washington’s Philadelphia household—only to be tracked down by the president’s men.

ISAAC GRANGER, who survived the devastation of Yorktown before returning to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.

PAUL JENNINGS, who was present at the burning of James Madison’s White House during the War of 1812.

ALFRED JACKSON, who was born into slavery at Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, survived the Civil War, and lived at the plantation into the 20th century.

These stories help us know the real people who were essential to the birth of this nation but traditionally have been left out of the history books. Their stories are true—and they should be heard.

Some of the hidden history from IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY

Five of the first seven presidents, and ten of the first fifteen, were slaveholders or raised in a slaveholding household.

George Washington once bought teeth from enslaved people to be used in his dentures.

For seven years as President Washington knowingly broke a Pennsylvania that freed enslaved people who lived in the state for more than six months.

Dozens of enslaved people from Jefferson’s Monticello, along with seventeen from Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation, were among thousands of African American refugees with the British in Yorktown, Virginia when American and French forces won the last battle in the Revolution.

The first man to write a memoir of working in the White House was formerly the enslaved valet of James Madison who witnessed the burning of the White House during the War of 1812.

Andrew Jackson went into debt to pay for the legal defense of four enslaved men from his Hermitage plantation who were tried for murder.

May 8, 2018

The first “Mother’s Day”-Some Hidden History

[Updated post]

Let me be among the first to say Happy Mother’s Day. Spouses, partners, and children everywhere: Don’t forget.

But amidst the brunches, flower-giving, and chocolate samplers, there is a story of another “Mother’s Day” that is worth remembering this weekend.

Julia Ward Howe, a prominent abolitionist best known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” published what became known as the “Mother’s Day Proclamation,” originally called “An Appeal to Womanhood Throughout the World.”

Julia Ward Howe (1907) Source: Library of Congress

In 1870, Howe wrote:

Our husbands shall not come to us reeking with carnage, for caresses and applause. Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy, and patience. . . . From the bosom of the devastated earth a voice goes up with our own. It says, Disarm, Disarm! The sword of murder is not the balance of justice! Blood does not wipe out dishonor nor violence indicate possession.

Source and Complete Text: Library of Congress

Howe’s international call for mothers to become the voice of pacifism found few takers. Even among like-minded women, there was greater urgency over the suffrage question. Her passionate campaign for a “Mother’s Day for Peace” begun in 1872 fell by the wayside.

Mother’s Day, as we know it, is not the invention of Hallmark; it started in 1912 through the efforts of West Virginia’s Anna Jarvis to create a holiday honoring all mothers for their sacrifice and to assist mothers who needed help.

Today, Mother’s Day is largely a commercial bonanza — flowers, chocolates and greeting cards. Is it possible to truly honor Howe’s version of Mother’s Day and work towards her original vision of Mother’s Day?

If only we remember the history behind the holiday and what she thought it should be.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah