Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 48

November 13, 2018

Two for Thanksgiving: Real First Pilgrims & Holiday’s History

Like the Macy’s parade, here is my Thanksgiving tradition. I post two articles about the holiday that I wrote for the New York Times.

The first, from 2008, is called “A French Connection” and tells the story of the real first Pilgrims in America. They were French. In Florida. Fifty years before the Mayflower sailed. It did not end with a happy meal. In fact, it ended in a religious massacre.

Illustration by Nathalie Lété in the New York Times

TO commemorate the arrival of the first pilgrims to America’s shores, a June date would be far more appropriate, accompanied perhaps by coq au vin and a nice Bordeaux. After all, the first European arrivals seeking religious freedom in the “New World” were French. And they beat their English counterparts by 50 years. That French settlers bested the Mayflower Pilgrims may surprise Americans raised on our foundational myth, but the record is clear.

The complete story can be found in America’s Hidden History.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

The second is “How the Civil War Created Thanksgiving” (2014) and tells the story of the Union League providing Thanksgiving dinners to Union troops.

Of all the bedtime-story versions of American history we teach, the tidy Thanksgiving pageant may be the one stuffed with the heaviest serving of myth. This iconic tale is the main course in our nation’s foundation legend, complete with cardboard cutouts of bow-carrying Native American cherubs and pint-size Pilgrims in black hats with buckles. And legend it largely is.

In fact, what had been a New England seasonal holiday became more of a “national” celebration only during the Civil War, with Lincoln’s proclamation calling for “a day of thanksgiving” in 1863.

Enjoy them both. Now for some football.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

November 9, 2018

Who Said It? (11-9-2018)

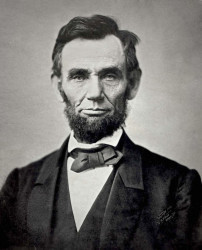

Abraham Lincoln “Thanksgiving Proclamation” (October 1863)

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

It has seemed to me fit and proper that they should be solemnly, reverently, and gratefully acknowledged as with one heart and one voice by the whole American people. I do, therefore, invite my fellow-citizens in every part of the United States, and also those who are at sea, and those who are sojourning in foreign lands, to set apart and observe the last Thursday of November next as a Day of Thanksgiving and Prayer to our beneficent Father who dwelleth in the heavens. And I recommend to them that, while offering up the ascriptions justly due to Him for such singular deliverances and blessings, they do also, with humble penitence for our national perverseness and disobedience, commend to His tender care all those who have become widows, orphans, mourners, or sufferers in the lamentable civil strife in which we are unavoidably engaged, and fervently implore the interposition of the Almighty hand to heal the wounds of the nation, and to restore it, as soon as may be consistent with the Divine purposes, to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquillity, and union.

November 8, 2018

11-11-11: Don’t Know Much About Veterans Day-The Forgotten Meaning

“The eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.”

(This is a revised version of a post originally written for Veterans Day in 2011. The meaning still applies.)

Taken at 10:58 a.m., on Nov. 11, 1918, just before the Armistice went into effect; men of the 353rd Infantry, near a church, at Stenay, Meuse, wait for the end of hostilities. (SC034981)

On Veterans Day, a reminder of what the day once meant and what it should still mean.

That was the moment at which World War I –then called THE GREAT WAR– largely came to end in 1918, on the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month.

One of the most tragically senseless and destructive periods in all history came to a close in Western Europe with the Armistice –or end of hostilities between Germany and the Allied nations — that began at that moment. Some 20 million people had died in the fighting that raged for more than four years since August 1914. The formal end of the war came with the Treaty of Versailles in June 1919.

Besides the war casualties, an estimated 100 million people died during the war of the Spanish flu, a worldwide pandemic that was completely linked to the war and had an impact on its outcome. That is the subject of my recent book, More Deadly Than War:The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War.

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and World War I

The date of November 11th became a national holiday of remembrance in many of the victorious allied nations –a day to commemorate the loss of so many lives in the war. And in the United States, President Wilson proclaimed the first Armistice Day on November 11, 1919. A few years later, in 1926, Congress passed a resolution calling on the President to observe each November 11th as a day of remembrance:

Whereas the 11th of November 1918, marked the cessation of the most destructive, sanguinary, and far reaching war in human annals and the resumption by the people of the United States of peaceful relations with other nations, which we hope may never again be severed, and

Whereas it is fitting that the recurring anniversary of this date should be commemorated with thanksgiving and prayer and exercises designed to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations; and

Whereas the legislatures of twenty-seven of our States have already declared November 11 to be a legal holiday: Therefore be it Resolved by the Senate (the House of Representatives concurring), that the President of the United States is requested to issue a proclamation calling upon the officials to display the flag of the United States on all Government buildings on November 11 and inviting the people of the United States to observe the day in schools and churches, or other suitable places, with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

Of course, the hopes that “the war to end all wars” would bring peace were short-lived. By 1939, Europe was again at war and what was once called “the Great War” would become World War I. With the end of World War II, there was a movement in America to rename Armistice Day and create a holiday that recognized the veterans of all of America’s conflicts. President Eisenhower signed that law in 1954. (In 1971, Veterans Day began to be marked as a Monday holiday on the third Monday in November, but in 1978, the holiday was returned to the traditional November 11th date).

Today, Veterans Day honors the duty, sacrifice and service of America’s nearly 25 million veterans of all wars, unlike Memorial Day, which specifically honors those who died fighting in America’s wars.

We should remember and celebrate all those men and women. But lost in that worthy goal is the forgotten meaning of this day in history –the meaning which Congress gave to Armistice Day in 1926:

to perpetuate peace through good will and mutual understanding between nations …

inviting the people of the United States to observe the day … with appropriate ceremonies of friendly relations with all other peoples.

The Library of Congress offers an extensive Veterans History Project.

The Veterans Administration website offers more resources on teaching about Veterans Day.

Read more about World War I and all of America’s conflicts in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

I discuss the role of Americans in battle in more than 240 years of American history in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah (Hachette Books and Random House Audio). My forthcoming book, MORE DEADLY THAN WAR: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War will be published in May 2018.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback and Random House audio)

October 28, 2018

Don’t Know Much About® Halloween–The Hidden History

(Video directed and produced by Colin Davis; originally posted October 2015)

When I was a kid in the early 1960s, the autumn social calendar was highlighted by the Halloween party in our church. In these simpler day, the kids all bobbed for apples and paraded through a spooky “haunted house” in homemade costumes –Daniel Boone replete with coonskin caps for the boys; tiaras and fairy princess wands for the girls. It was safe, secure and innocent.

The irony is that our church was a Congregational church — founded by the Puritans of New England. The same people who brought you the Salem Witch Trials.

Here’s a link to a history of those Witch Trials in 1692.

Rooted in pagan traditions more than 2000 years old, Halloween grew out of a Celtic Druid celebration that marked summer’s end. Called Samhain (pronounced sow-in or sow-een), it combined the Celts’ harvest and New Year festivals, held in late October and early November by people in what is now Ireland, Great Britain and elsewhere in Europe. This ancient Druid rite was tied to the seasonal cycles of life and death — as the last crops were harvested, the final apples picked and livestock brought in for winter stables or slaughter. Contrary to what some modern critics believe, Samhain was not the name of a malevolent Celtic deity but meant, “end of summer.”

The Celts also saw Samhain as a fearful time, when the barrier between the worlds of living and dead broke, and spirits walked the earth, causing mischief. Going door to door, children collected wood for a sacred bonfire that provided light against the growing darkness, and villagers gathered to burn crops in honor of their agricultural gods. During this fiery festival, the Celts wore masks, often made of animal heads and skins, hoping to frighten off wandering spirits. As the celebration ended, families carried home embers from the communal fire to re-light their hearth fires.

Getting the picture? Costumes, “trick or treat” and Jack-o-lanterns all got started more than two thousand years ago at an Irish bonfire.

Christianity took a dim view of these “heathen” rites. Attempting to replace the Druid festival of the dead with a church-approved holiday, the seventh-century Pope Boniface IV designated November 1 as All Saints’ Day to honor saints and martyrs. Then in 1000 AD, the church made November 2 All Souls’ Day, a day to remember the departed and pray for their souls. Together, the three celebrations –All Saints’ Eve, All Saints’ Day, and All Souls Day– were called Hallowmas, and the night before came to be called All-hallows Evening, eventually shortened to “Halloween.”

And when millions of Irish and other Europeans emigrated to America, they carried along their traditions. The age-old practice of carrying home embers in a hollowed-out turnip still burns strong. In an Irish folk tale, a man named Stingy Jack once escaped the devil with one of these turnip lanterns. When the Irish came to America, Jack’s turnip was exchanged for the more easily carved pumpkin and Stingy Jack’s name lives on in “Jack-o-lantern.”

Halloween, in other words, is deeply rooted in myths –ancient stories that explain the seasons and the mysteries of life and death.

October 16, 2018

Pop quiz: What did Washington get when the British surrendered at Yorktown?

(Original post updated 10/18/2018)

Answer: All of the enslaved people in Yorktown who had escaped to the British in hopes of freedom.

Surrender of Lord Cornwallis by John Trumbull (Source: Architect of the U.S. Capitol)

When the British forces under Cornwallis surrendered to George Washington and his French allies on October 19, 1781, the terms of capitulation included the following phrase

It is understood that any property obviously belonging to the inhabitants of these States, in the possession of the garrison, shall be subject to be reclaimed.

(Article IV, Articles of Capitulation; dated October 18, 1781. Source and Complete Text: Avalon Project-Yale Law School)

Thousands of escaped enslaved people had flocked to the British army during Cornwallis’s campaign in Virginia in what has been called the “largest slave rebellion in American history.”

They had come in the belief that the British would free them. Cornwallis had put them to work on the British defense works around the small tobacco port, and when disease started to spread and supplies ran low, Cornwallis forced hundreds of these people out of Yorktown. Many more died from epidemic diseases and the shelling of American and French artillery during the siege.

The African Americans in Yorktown included at least seventeen people who had left Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation with the British, as well as members of Thomas Jefferson’s enslaved community also captured earlier in 1781. They were all returned to bondage, along with thousands of others as Virginian slaveholders came to Yorktown to recover their “property.”

Isaac Granger Jefferson at about age 70 (Courtesy: Tracy W. McGregor Library of American History, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library)

Among them was Isaac Granger Jefferson, a five-year-old boy who was returned to Monticello and later told his story.

The stories of some of the people “reclaimed” by Washington are told in my book, IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives.

The Battle of Yorktown and role of African-American soldiers there –as well as the fate of the enslaved people in the besieged town — are featured in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

“A fascinating exploration of war and the myths of war. Kenneth C. Davis shows how interesting the truth can be.” –Evan Thomas, New York Times-bestselling author of Sea of Thunder and John Paul Jones

October 9, 2018

Pop Quiz: Who first used the words “Wall of Separation” in talking about church and state?

Answer: Roger Williams, the dissident minister banished by the General Court of the Massachusetts Bay Colony on October 9, 1635. Williams was told to leave the colony within six weeks. If he returned, he risked execution. He eventually went on to found Rhode Island, with a written constitution guaranteeing freedom of religion, approved by Parliament in 1644.

Williams died in Rhode Island in 1683. Learn more at the Roger Williams National Memorial (U.S. National Park Service).

As Williams biographer John M. Barry wrote:

Williams described the true church as a magnificent garden, unsullied and pure, resonant of Eden. The world he described as “the Wilderness,” a word with personal resonance for him. Then he used for the first time a phrase he would use again, a phrase that although not commonly attributed to him has echoed through American history. “[W]hen they have opened a gap in the hedge or wall of Separation between the Garden of the Church and the Wildernes of the world,” he warned, “God hathe ever broke down the wall it selfe, removed the Candlestick, &c. and made his Garden a Wildernesse.”

Read more: “God, Government and Roger Williams’ Big Idea” by John M. Barry in Smithsonian magazine

The phrase, “wall of separation between church and state” does not appear in the United States Constitution as many people think. But it was used in a famous letter written by Thomas Jefferson in 1802.

As I wrote in a 2011 essay, “Why U.S. is Not a Christian Nation,”

The idea was not Jefferson’s. Other 17th- and 18th-century Enlightenment writers had used a variant of it. Earlier still, religious dissident Roger Williams had written in a 1644 letter of a “hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world.”

Williams, who founded Rhode Island with a colonial charter that included religious freedom, knew intolerance firsthand. He and other religious dissenters, including Anne Hutchinson, had been banished from neighboring Massachusetts, the “shining city on a hill” where Catholics, Quakers and Baptists were banned under penalty of death.

According to the Library of Congress:

This phrase has become well known because it is considered to explain (many would say, distort) the “religion clause” of the First Amendment to the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion …,” a clause whose meaning has been the subject of passionate dispute for the past 50 years.

Read more about Jefferson’s letter and the phrase: “A Wall of Separation” by James Hutson, a curator at the Library of Congress

October 4, 2018

Who Said it (10/4/2018)

I found it (the world) was not round . . . but pear shaped.

Christopher Columbus — Log of his third voyage (1498)

I found it (the world) was not round . . . but pear shaped, round where it has a nipple, for there it is taller, or as if one had a round ball and, on one side, it should be like a woman’s breast, and this nipple part is the highest and closest to Heaven.

–Christopher Columbus, Log of his third voyage (1498)

Read more about the Columbus story and watch a Don’t Know Much About Minute here.

September 24, 2018

A Parade More Deadly Than War

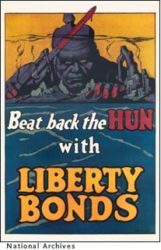

It was a parade like none Philadelphia had ever seen.

In the summer of 1918, as the Great War raged and American doughboys fell on Europe’s killing fields, the City of Brotherly Love organized a grand spectacle. To bolster morale and support the war effort, a procession for the ages brought together marching bands, Boy Scouts, women’s auxiliaries, and uniformed troops to promote Liberty Loans –government bonds issued to pay for the war. The day would be capped off with a concert led by the “March King” himself –John Philip Sousa.

The city sought to sell Liberty Loans, bonds to pay for the war effort, while bringing its citizens together during the infamous pandemic.

Read the complete article: “Philadelphia Threw a WWI Parade That Gave Thousands of Onlookers the Flu” from Smithsonian Magazine

Read more: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/histor...

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and World War I -Coming MAY 2018

September 3, 2018

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War (Available May 15)

Now available, this book recounts the story of the most deadly epidemic in modern times, the Spanish Flu pandemic, which struck the world 100 years ago during the last months of World War I. While U.S. doughboys joined the largest offensive in American military history (Meuse-Argonne) that began in late September 1918, the Spanish flu pandemic returned to America with devastating virulence and violence. It is an unforgettable story that has been forgotten.

The book and audio versions are available for preorder and links to online sellers can be found here.

Davis (In the Shadow of Liberty) immediately sets the urgent tone of his forthright chronicle, citing staggering statistics: the Spanish Flu pandemic that began in spring 1918 claimed the lives of more than 675,000 Americans in a single year and left a worldwide death toll estimated at 100 million. The author structures his exhaustive account of the origins, transmission, and consequences of the pandemic within the framework of WWI, underscoring the lethal concurrence of these “twin catastrophes.”

Invisible. Incurable. Unstoppable.

From bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis comes a fascinating account of the Spanish influenza pandemic that swept the world from 1918 to 1919.

With 2018 marking the centennial of the worst disease outbreak in modern history, the story of the Spanish flu is more relevant today than ever. This dramatic narrative, told through the stories and voices of the people caught in the deadly maelstrom, explores how this vast, global epidemic was intertwined with the horrors of World War I – and how it could happen again. Complete with photographs, period documents, modern research, and firsthand reports by medical professionals and survivors, this book provides captivating insight into a catastrophe that transformed America in the early twentieth century.

Listen to a sample of the Audio version coming from Penguin Random House Audio.

I hope you will also read my previous book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

August 20, 2018

Who Said It (8/20/18)

President Abraham Lincoln, First Annual Message (December 3, 1861)

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labor of community exists within that relation. A few men own capital, and that few avoid labor themselves, and with their capital hire or buy another few to labor for them. A large majority belong to neither class–neither work for others nor have others working for them. In most of the Southern States a majority of the whole people of all colors are neither slaves nor masters, while in the Northern a large majority are neither hirers nor hired. Men, with their families–wives, sons, and daughters–work for themselves on their farms, in their houses, and in their shops, taking the whole product to themselves, and asking no favors of capital on the one hand nor of hired laborers or slaves on the other.

Source: Abraham Lincoln: “First Annual Message,” December 3, 1861. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

For a history of the roots of Labor Day, read “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day

Or watch this brief animated video I did with Ted ED: “Why do Americans and Canadians Celebrate Labor Day?