Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 47

January 24, 2019

Don’t Know Much About® Edith Wharton

(originally posted on 1/24/2013; revised 1/24/2019)

[image error]

A plaque honoring Edith Wharton in Paris (Photo: Courtesy of Radio France International)

Born today in New York City in 1862: Edith Newbold Jones, who achieved fame as Edith Wharton, the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1921 (for The Age of Innocence).

Romance, scandal and ruin among New York socialites—long before this was the stuff of People, and “Gossip Girl,” it was the subject matter for Edith Wharton’s most famous works. In such novels as The House of Mirth (1905) and The Age of Innocence (1920), Wharton painted detailed, acid portraits of high society life. In doing so, she created heartbreaking conflicts beneath the façade of wealth and manners. Again and again, characters like Newland Archer and Lily Bart were forced to choose between conforming to social expectations and pursuing true love and happiness.

Edith Wharton in France during World War I (Photo: Courtesy The Mount Edith Wharton’s Home)

The other lesser-known aspect of Wharton’s life is her experience in France during World War I, where she founded hospitals and refugee centers for women and children. She also wrote urging the United States to join the war.

American novelist Edith Wharton set up workshops for women all over Paris, making clothes for hospitals as well as lingerie for a fashionable clientele. She raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for refugees and tuberculosis sufferers and ran a rescue committee for the children of Flanders, whose towns were bombarded by the Germans. Her friend and fellow author Henry James called her the “great generalissima”.

Source: Radio France International: “Edith Wharton-The American novelist who joined France’s WWI effort”

Her most famous work set outside the realm of high-tone New York was Ethan Frome (1911), set in wintry, rural Massachusetts.

Know your Wharton? Try this quick quiz–

TRUE or FALSE (Quiz adapted from Don’t Know Much About Literature, written with Jenny Davis-Answers below)

1. Edith Wharton wrote about wealthy New Yorkers to escape the poverty of her own upbringing.

2. Though Edith Wharton was unhappily married, she could not get divorced because it was socially unacceptable.

3. In addition to her fiction, Wharton published several books on interior decorating and landscaping.

The Mount is Wharton’s restored home in the Berkshires in Massachusetts.

The Edith Wharton Collection of manuscripts, correspondence and photographs is housed at Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library.

Edith Wharton died in France in August 1937. Here is her New York Times: obituary.

Answers

1. FALSE. Wharton was born to wealthy New Yorkers, and summered in Newport, Rhode Island. She grew up traveling through Europe, and was educated by private tutors. After an official debut into society, she married a rich banker twelve years her senior.

2. FALSE. She divorced Teddy Wharton in 1913.

3. TRUE. Her first book was The Decoration of Houses, establishing her fame as a writer. She also wrote about Italian landscaping and architecture in Italian Villas and Their Gardens, illustrated by Maxfield Parrish.

January 10, 2019

Whatever Became of Thomas Paine?

Thomas Paine ©National Portrait Gallery London copy by Auguste Millière, after an engraving by William Sharp, after George Romney oil on canvas, circa 1876

Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.

-Thomas Paine Common Sense

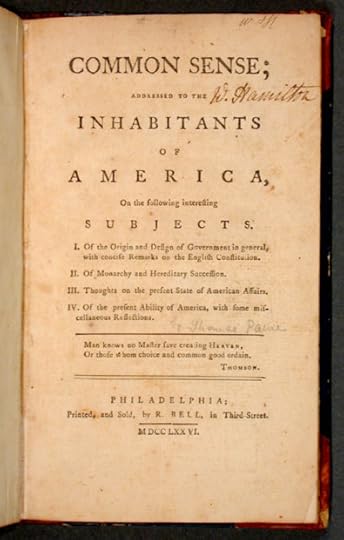

One of the most significant pieces of writing in American history was published on January 10, 1776. It was Thomas Paine’s essay Common Sense and is widely credited with helping to rouse Americans to the patriot cause. Its sales were extraordinary at the time; given the American population today, current day sales would amount to some 60 million copies.

Common Sense Source: Library of Congress

The pamphleteering Paine is best known for Common Sense and The Crisis, among other works that supported the cause of independence. But after the Revolution, Paine returned to his native England and later went to France, then in the throes of its Revolution. Paine was caught up in the complex politics of the bloody Revolution there, eventually winding up in a French prison cell, facing the prospect of the guillotine.

After eventually being freed, Paine wrote an open letter in 1796 angrily denouncing President George Washington for failing to do enough to secure his release.

“Monopolies of every kind marked your administration almost in the moment of its commencement. The lands obtained by the Revolution were lavished upon partisans; the interest of the disbanded soldier was sold to the speculator…In what fraudulent light must Mr. Washington’s character appear in the world, when his declarations and his conduct are compared together!”

Source: George Washington’s Mount Vernon

This was a serious case of bridge-burning and Paine swiftly fell from grace in America. But apart from dissing the Father of the Country, Paine had also fallen from favor for his most famous work after Common Sense. In 1794, he had published The Age of Reason (Part I), a deist assault on organized religion and the errors of the Bible. In it, Paine had written:

I do not believe in the creed professed by the Jewish church, by the Roman church, by the Greek church, by the Turkish church, by the Protestant church, nor by any church that I know of. My own mind is my own church.

All national institutions of churches, whether Jewish, Christian or Turkish, appear to me no other than human inventions, set up to terrify and enslave mankind, and monopolize power and profit.

(Source: USHistory.org)

After returning to the United States, which owed so much to him, Paine was regarded as an atheist and was abandoned by most of his friends and former allies. He died in disgrace, an outcast from the United States he had helped create. The Quaker church he had rejected refused to bury him after he died in Greenwich Village (New York) in 1809. He was buried on his farm in New Rochelle, New York. A handful of people attended his funeral.

An admirer brought this remains back to England for reburial there, but they were lost.

You can read more about Thomas Paine, his relationship with Washington and his ultimate fate in Don’t Know Much About History and Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents.

January 8, 2019

IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY-now in paperback

While waiting for the arrival of More Deadly Than War (May 15) do check out In The Shadow Of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives

•Notable Children’s Books-2017 ALSC/ALA

•A FINALIST for 2017 Award for Excellence in Young Adult Nonfiction by YALSA — the Young Adult Library Services Association of the American Library Association.

•A selection of the 2018 Tayshas Reading List/Texas Library Association

•Named one of the BEST CHILDREN’S AND YOUNG ADULT BOOKS OF 2016 (Washington Post)

Did you know that many of America’s Founding Fathers—who fought for liberty and justice for all—were slave owners?

Through the powerful stories of five enslaved people who were “owned” by four of our greatest presidents, this book helps set the record straight about the role slavery played in the founding of America. These dramatic narratives explore our country’s great tragedy—that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

BILLY LEE, who became George Washington’s valet and fought in the American Revolution alongside him.

ONA JUDGE, who escaped from Washington’s Philadelphia household—only to be tracked down by the president’s men.

ISAAC GRANGER, who survived the devastation of Yorktown before returning to Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello.

PAUL JENNINGS, who was present at the burning of James Madison’s White House during the War of 1812.

ALFRED JACKSON, who was born into slavery at Andrew Jackson’s Hermitage, survived the Civil War, and lived at the plantation into the 20th century.

These stories help us know the real people who were essential to the birth of this nation but traditionally have been left out of the history books. Their stories are true—and they should be heard.

Some of the hidden history from IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY

Five of the first seven presidents, and ten of the first fifteen, were slaveholders or raised in a slaveholding household.

George Washington once bought teeth from enslaved people to be used in his dentures.

For seven years as President Washington knowingly broke a Pennsylvania that freed enslaved people who lived in the state for more than six months.

Dozens of enslaved people from Jefferson’s Monticello, along with seventeen from Washington’s Mount Vernon plantation, were among thousands of African American refugees with the British in Yorktown, Virginia when American and French forces won the last battle in the Revolution.

The first man to write a memoir of working in the White House was formerly the enslaved valet of James Madison who witnessed the burning of the White House during the War of 1812.

Andrew Jackson went into debt to pay for the legal defense of four enslaved men from his Hermitage plantation who were tried for murder.

IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY Published by Henry Holt & Co. | On sale September 20, 2016 ISBN: 978-1-62779-311-7 | Hardcover | Ages 10 and up | 304 pages | $17.99

Available in Audio from Penguin Random House

Who Said It? (1/8/2019)

George Washington, First Annual Address to Congress (January 8, 1790)

Nor am I less persuaded that you will agree with me in opinion that there is nothing which can better deserve your patronage than the promotion of science and literature. Knowledge is in every country the surest basis of public happiness. In one in which the measures of government receive their impressions so immediately from the sense of the community as in ours it is proportionably essential.

Complete Text and Source: The American Presidency Project, UC Santa Barbara

Under the terms of the Constitution, Washington delivered this message to Congress in person. It would later be called the State of the Union address.

Read more from Washington’s Mount Vernon Plantation.

January 4, 2019

Who Said It? (5/19/2014)

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964)

(Photo: Arnold Newman, WHite House Press Office)

(Revised January 4, 2019)

Johnson’s “Great Society” idea was also presented in his State of the Union Address on January 4, 1965.

New York Times report on the speech.

Video and Transcript of the Johnson’s State of the Union address

President Lyndon B. Johnson, “The Great Society” Speech (University of Michigan, May 22. 1964)

Each year more than 100,000 high school graduates with proved ability do not enter college because they cannot afford it. And if we cannot educate today’s youth, what will we do in 1970 when elementary school enrollment will be five million greater than 1960? And high school enrollment will rise by five million. And college enrollment will increase by more than three million.

In many places, classrooms are overcrowded and curricula are outdated. Most of our qualified teachers are underpaid, and many of our paid teachers are unqualified. So we must give every child a place to sit and a teacher to learn from. Poverty must not be a bar to learning, and learning must offer an escape from poverty.

But more classrooms and more teachers are not enough. We must seek an educational system which grows in excellence as it grows in size. And this means better training for our teachers. It means preparing youth to enjoy their hours of leisure, as well as their hours of labor. It means exploring new techniques of teaching, to find new ways to stimulate the love of learning and the capacity for creation.

Source: American Experience-PBS: “LBJ”

A few months after declaring a “War on Poverty,” President Lyndon B. Johnson outlined his ambitious domestic agenda to end poverty, improve the status of African Americans and create a more equal and just American society. In the speech Johnson said,

The Great Society rests on abundance and liberty for all. It demands an end to poverty and racial injustice, to which we are totally committed in our time. But that is just the beginning.

The range of programs that were introduced fifty years ago included Medicare, Medicaid, food stamps, Head Start, and the Job Corps.

In April 2014, New York Times reporter Trip Gabriel assessed the War on Poverty half a century later in “Fifty Years Into the War on Poverty, Hardship Hits Back.”

President Johnson was a schoolteacher in a poor, rural district in Texas before entering politics. Read more about his life, administration and legacy in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About History.

December 28, 2018

Who Said It (12/28/2018)

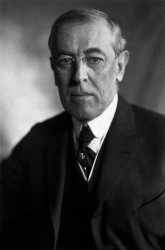

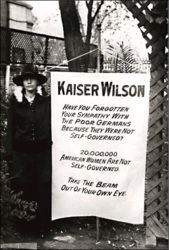

President Woodrow Wilson War Message to Joint Session of Congress: April 2, 1917

Thomas Woodrow Wilson 28th POTUS (1918) Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts,-for democracy…

Source and Complete Transcript of Wilson’s Speech via National Archives

Don’t Know Much About® Woodrow Wilson

“Who was the last president born in a slave holding household?”

Thomas Woodrow Wilson 28th President (1918) Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA

It might seem like a piece of trivia. But the answer is not trivial. President Woodrow Wilson was born in Staunton, Virginia, on December 28 ,1856, the last of eight presidents born in Virginia. He was the son of a Presbyterian minister who did not own slaves himself. But the house in which Wilson was born was the property of the church Wilson’s father led and slaves came with the house. His father was a leader in the creation of the Southern Presbyterian Church which split from the main body of the church over slavery in 1861. Born Thomas Woodrow Wilson, the 28th was raised in Virginia, Georgia, and South Carolina. He later recalled seeing Robert E. Lee as small child.

Wilson was elected in 1912 after one of the most extraordinary campaigns in presidential history. He defeated both the incumbent Republican William Howard Taft and third-party candidate Theodore Roosevelt.

Fast Facts

-Wilson was the first and to date only president with a Ph.D. He had also served as the President of Princeton before becoming Governor of New Jersey.

-Wilson’s first wife Ellen Louise Wilson died in the White House of “Bright’s disease” (kidney failure) on August 6, 1914.

-Wilson married Edith Galt Wilson on December 18, 1915 in the home of the bride in Washington, D.C. Their engagement and wedding caused some scandal at the time coming only a little more than a year after the death of Wilson’s first wife.

-Edith Galt Wilson accompanied her husband to and from the Capitol at his second inaugural in 1917, establishing a new tradition. It was also the first Inaugural Parade in which women participated.

-Wilson delivered the annual message to Congress (“State of the Union”) to a joint session of Congress in person in 1913, the first time a president had done so since Thomas Jefferson began sending a written message in 1803. He also also established a tradition of regular press conferences.

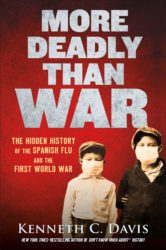

_While negotiating the Versailles Treaty in France following the end of World War I, Wilson fell ill with the flu. The illness, which may have been “Spanish Influenza,” left him weak and seemed to change Wilson, leading to speculation that the illness affected his decision-making at this crucial moment in history. Read more in More Deadly Than War

-Wilson collapsed on September 25, 1919 and suffered a stroke, leaving him partially paralyzed. His wife, Edith, kept him sequestered in the White House for five weeks, in one of the most serious cases of presidential disability in history. During this time, Edith Wilson served as his “steward,” as she described it, selecting which business he could tend to and making at least one important policy decision.

The Woodrow Wilson Presidential Library is in Staunton, Virginia adjacent to the Woodrow Wilson birthplace.

December 26, 2018

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War

Now available, this book recounts the story of the most deadly epidemic in modern times, the Spanish Flu pandemic, which struck the world 100 years ago during the last months of World War I. While U.S. doughboys joined the largest offensive in American military history (Meuse-Argonne) that began in late September 1918, the Spanish flu pandemic returned to America with devastating virulence and violence. It is an unforgettable story that has been forgotten.

The book and audio versions are available for preorder and links to online sellers can be found here.

Davis (In the Shadow of Liberty) immediately sets the urgent tone of his forthright chronicle, citing staggering statistics: the Spanish Flu pandemic that began in spring 1918 claimed the lives of more than 675,000 Americans in a single year and left a worldwide death toll estimated at 100 million. The author structures his exhaustive account of the origins, transmission, and consequences of the pandemic within the framework of WWI, underscoring the lethal concurrence of these “twin catastrophes.”

Invisible. Incurable. Unstoppable.

From bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis comes a fascinating account of the Spanish influenza pandemic that swept the world from 1918 to 1919.

With 2018 marking the centennial of the worst disease outbreak in modern history, the story of the Spanish flu is more relevant today than ever. This dramatic narrative, told through the stories and voices of the people caught in the deadly maelstrom, explores how this vast, global epidemic was intertwined with the horrors of World War I – and how it could happen again. Complete with photographs, period documents, modern research, and firsthand reports by medical professionals and survivors, this book provides captivating insight into a catastrophe that transformed America in the early twentieth century.

Listen to a sample of the Audio version coming from Penguin Random House Audio.

I hope you will also read my previous book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

December 21, 2018

Winter Solstice: The “Reason for the Season”

The 2018 Winter Solstice arrives today, December 21, 2018. So ’tis a perfect day to talk about the real “reason for the season.”

And here’s the real first Christmas question: Why all the fuss over December 25?

For starters, the Gospels never mention a precise date or even a season for the birth of Jesus. How then did we settle on December 25 and all those festive lights?

If a bright light just went off in your head, you’re getting warm. It’s largely about the Sun.

In ancient times, a popular Roman festival celebrated Saturnalia, a Thanksgiving-like holiday marking the winter solstice and honoring Saturn, the god of agriculture. The Saturnalia began on December 17th and while it only lasted two days at first, it was eventually extended into a weeklong period that lost its agricultural significance and simply became a time of general merriment. Even slaves were given temporary freedom to do as they pleased, while the Romans feasted, visited one another, lit candles and gave gifts. Later it was changed to honor the official Roman Sun god known as Sol Invictus (“Unconquered Sun”) and the solstice fell on December 25.

Two other important pagan gods popular in ancient Rome were also celebrated around this date. The Roman were big on adopting the gods of the people they conquered. Mithra, a Persian god of light who was first popular among Roman soldiers, acquired a large cult in ancient Rome. The birth of Attis, another agricultural god from Asia Minor, was also celebrated on December 25. Attis dies but is brought back to life by his lover, a goddess whose temple later became the site of an important basilica honoring the Virgin Mary. By the way, the symbol of Attis was a pine tree.

Candles. Gift giving. Pine trees. Dying gods brought back to life. Hmmm. Sound familiar?

All the similarities between Saturnalia and these other Roman holidays and the celebration of Christmas are no coincidence. In the fourth century, Pope Julius 1 assigned December 25 as the day to celebrate the Mass of Christ’s birth –Christ’s mass. This was a clever marketing ploy that conveniently sidestepped the problem of eliminating an already popular holiday while converting the population.

There is a scholarly argument that the December 25 date was marked earlier in some Christian communities, as argued by Yale Divinity school Dean Andrew McGowan. But the official recognition by the Pope cemented the date for many Christians. In other Christian communities, January 6 –the Epiphany, or the day the magi visited the infant Jesus– was considered more significant. The period between these dates also accounts for the “Twelve Days of Christmas.” Other authorities disagree and say that December date was arrived at by adding nine months to March 25, the Feast of the Annunciation, the day of Jesus’s miraculous conception.

But most modern Christmas traditions reflect the merger of pagan rituals, beliefs, and traditions with Christianity. The early church fathers knew that they couldn’t convert people without allowing them to keep some of their ancient festivals and rituals so they would allow them if they could be connected to Christianity.

The importance of the winter solstice, then, is crucial to understanding many of the other traditions of this season. Evergreen trees, mistletoe, holly, and Yule logs all relate back to pre-Christian practices and symbols that celebrate the return of light and life after the Solstice. That’s why the Puritans rejected Christmas celebrations under Cromwell and in the Massachusetts colony in 1659. (Read my post Who Started the War on Christmas?“)

While we are talking about dates, the precise year of the birth of Jesus is also a mystery. The dating system we use is based on a system devised by a monk around 1500 years ago and is seriously flawed. The historical King Herod who ordered the massacre of the innocents died in 4 BC (or BCE, Before the Common Era). The “census” ordered by Emperor Augustine is not recorded in Roman history, but a local census did take place in the Roman province of Judea in 6 AD (or CE, the Common Era). Is that all perfectly clear now?

You can read more about the mythic roots of Christmas and the gospel accounts of Jesus in Don’t Know Much About Mythology and Don’t Know Much About the Bible.

November 29, 2018

Who Started the “War on Christmas?”

“In the interest of labor and morality” (1895: Image Courtesy of Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.print)

(Revision of post first published 12.11.2103)

It’s that time of year. Cue the lights, decorations, music.… and the “War on Christmas.”

Proclaiming a secular assault on the religious significance of the holiday has become a seasonal staple, just like the Macy’s Parade with Santa Claus. Saying “Merry Christmas” became a 2016 campaign talking point and it has been a staple of conservative talk show hosts for years.

The basic premise: Christmas is under attack by Grinchy atheists and secular humanists who want to remove any vestige of Christianity from the public space. Any criticism of public displays devoted to religious symbols –mangers, crosses, stars — is seen by these folks as part of a wider attack on “Christian values” in America. Mass market retailers who substituted “Happy Holidays” for “Merry Christmas” are part of the conspiracy to “ruin Christmas.”

But in fact, most religious displays are not banned. Courts simply direct that one religion cannot be favored over another under the Constitutional protections of the First Amendment. Christmas displays are generally permitted as long as menorahs, Kwanzaa displays, and other seasonal symbols are also allowed.

In other words, the “War on Christmas” is pretty much a phony war. But where did this all start?

The first laws against Christmas celebrations and festivities in America came during the 1600s –from the same wonderful folks who brought you the Salem Witch Trials — the Puritans. (By the way, H.L. Mencken once defined Puritanism as the fear that “somewhere someone may be happy.”)

“For preventing disorders, arising in several places within this jurisdiction by reason of some still observing such festivals as were superstitiously kept in other communities, to the great dishonor of God and offense of others: it is therefore ordered by this court and the authority thereof that whosoever shall be found observing any such day as Christmas or the like, either by forbearing of labor, feasting, or any other way, upon any such account as aforesaid, every such person so offending shall pay for every such offence five shilling as a fine to the county.”

–From the records of the General Court,

Massachusetts Bay Colony

May 11, 1659

The Founding Fathers of the Massachusetts Bay Colony were not a festive bunch. To them, Christmas was a debauched, wasteful festival that threatened their core religious beliefs. They understood that most of the trappings of Christmas –like holly and mistletoe– were vestiges of ancient pagan rituals. More importantly, they thought Christmas — the mass of Christ– was too “popish,” by which they meant Roman Catholic. These are the people who banned Catholic priests from Boston under penalty of death.

This sensibility actually began over the way in which Christmas was celebrated in England. Oliver Cromwell, a strict Puritan who took over England in 1645, believed it was his mission to cleanse the country of the sort of seasonal moral decay that Protestant writer Philip Stubbes described in the 1500s:

‘More mischief is that time committed than in all the year besides … What dicing and carding, what eating and drinking, what banqueting and feasting is then used … to the great dishonour of God and the impoverishing of the realm.’

In 1644, Parliament banned Christmas celebrations. Attending mass was forbidden. Under Cromwell’s Commonwealth, mince pies, holly and other popular customs fell victim to the Puritan mission to remove all merrymaking during the Christmas period. To Puritans, the celebration of the Lord’s birth should be day of fasting and prayer.

In England, the Puritan War on Christmas lasted until 1660. In Massachusetts, the ban remained in place until 1687.

So if the conservative broadcasters and religious folk really want a traditional, American Christian Christmas, the solution is simple — don’t have any fun.

Read more about the Puritans in Don’t Know Much About® History and America’s Hidden History. The history behind Christmas is also told in Don’t Know Much About® The Bible.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)