Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 46

May 30, 2019

Who Said It?

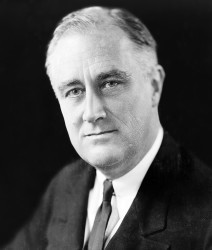

Seventy-five years ago, on the night of June 6, 1944, President Roosevelt went on national radio to discuss the invasion of Normandy — D-Day — with the American people.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “D-Day Prayer” (June 6, 1944)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “D-Day Prayer” (June 6, 1944)

Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.

Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest-until the victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and flame. Men’s souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

His address took the form of this prayer. (Full text from Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum)

May 28, 2019

D-Day- 75th Anniversary

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “D-Day Prayer” in an announcement to the nation of the invasion of Normandy (June 6, 1944)

Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933

My fellow Americans: Last night, when I spoke with you about the fall of Rome, I knew at that moment that troops of the United States and our allies were crossing the Channel in another and greater operation. It has come to pass with success thus far.

And so, in this poignant hour, I ask you to join with me in prayer:

Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.

Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest-until the victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and flame. Men’s souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

Franklin Roosevelt’s D-Day Prayer Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum

Steven Spielberg’s World War II epic, Saving Private Ryan, brought the brutal reality of combat home to millions, but many moviegoers did not know which battle the film depicted, or when and why it happened. The assault, code-named Operation Overlord, occurred June 6, 1944, against Hitler’s Germany. In the largest amphibian assault in history, Allied armies crossed the English Channel to land on five beaches in Normandy in northern France. The invasion force involved 700 ships, 4,000 landing craft, 10,000 planes, and some 176,000 Allied troops. The allied forces were commanded by future President, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The German army did not formally surrender until May 7, 1945. May 8, 1945 was declared V.E. (Victory in Europe) Day.

More D-Day resources can be found at the FDR Library and Museum

Read more about FDR’s life and administration and World War II in Don’t Know Much About® History and Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

May 26, 2019

Veterans, Poppies, and “In Flanders Fields”

Soldiers of the 146th Infantry, 37th Division, crossing the Scheldt River at Nederzwalm under fire. Image courtesy of The National Archives.

One of the most famous symbols of the sacrifice and loss we mark on Memorial Day and Veterans Day is the Poppy, inspired by this World War I poem, “In Flanders Fields,” written by John McCrae.

John McCrae, a Canadian doctor and teacher who is best known for his memorial poem “In Flanders Fields,”

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place, and in the sky,

The larks, still bravely singing, fly,

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead; short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe!

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high!

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Source: The poem is in the public domain courtesy of Poets.org

“Soon after writing “In Flanders Field,” McCrae was transferred to a hospital in France, where he was named the chief of medical services. Saddened and disillusioned by the war, McCrae found respite in writing letters and poetry, and wrote his final poem, “The Anxious Dead.”

In the summer of 1917, McCrae’s health took a turn, and he began suffering from severe asthma attacks and bronchitis. McCrae died of pneumonia and meningitis on January 28, 1918.” (Poets.org)

Inspired by McCrae’s poem, an American woman, Moina Michael originated the idea of wearing red poppies to honor the war dead. She sold poppies with the money going to benefit servicemen, and the movement caught on, spreading to Europe as well. In 1948, Moina Michael was honored for founding the Poppy Movement with a red 3 cent postage stamp.

May 21, 2019

Don’t Know Much About® Memorial Day

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= (This video was originally posted May 2012. It was produced, edited and directed by Colin Davis.)

Memorial Day brings thoughts of duty, honor, courage, sacrifice and loss. The holiday, the most somber date on the American national calendar, was born in the ashes of the Civil War as “Decoration Day,” when General John S. Logan –a-veteran of the Mexican and Civil Wars, a prominent Illinois politician and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, a Union fraternal organization –called for May 30, 1868 as the day on which the graves of fallen Union soldiers would be decorated with fresh flowers in his “General Orders No. 11.”

“We should guard their graves with sacred vigilance. All that the consecrated wealth and taste of the Nation can add to their adornment and security is but a fitting tribute to the memory of her slain defenders. Let no wanton foot tread rudely on such hallowed grounds.”

Pointedly, Logan’s order was seen as a day to honor those who died in the cause of ending slavery and opposing the “rebellion.”

Every year at this time, I spend a lot of time talking about the roots and traditions of Memorial Day.

It’s not about the barbecue or the Mattress Sales. Obscured by the holiday atmosphere around Memorial Day is the fact that it is the most solemn day on the national calendar. This video tells a bit about the history behind the holiday.

Soldiers of the 146th Infantry, 37th Division, crossing the Scheldt River at Nederzwalm under fire. Image courtesy of The National Archives.

One of the most famous symbols of the loss on Memorial Day is the Poppy, inspired by this World War I poem by John McCrae, “In Flanders Fields”

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place, and in the sky,

The larks, still bravely singing, fly,

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the dead; short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe!

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high!

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Source: The poem is in the public domain courtesy of Poets.org

Have a memorable Memorial Day!

The U.S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs offers more resources on the history and traditions of Memorial Day.

(Images in video: Courtesy of the Library of Congress and Flanders Cemetery image Courtesy of the American Battle Monuments Commission)

May 14, 2019

Don’t Know Much About® the Tonkin Resolution

[8/2016 post updated 5/15/2019]

“Charges that four oil vessels were attacked at the mouth of the Persian Gulf over the weekend have amplified fears across the region about the escalating tensions between Iran and the West.” New York Times, May 13, 2019

Ships attacked. U.S. military response ratcheted up. Been there, done that. It did not end well.

What was the Tonkin Resolution?

Photograph taken from USS Maddox (DD-731) during her engagement with three North Vietnamese motor torpedo boats in the Gulf of Tonkin, 2 August 1964. (Courtesy of the U.S. Naval Historical Cente)r

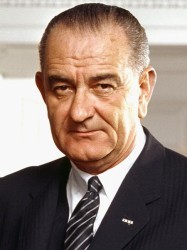

On August 7, 1964, Congress approved a resolution that soon became the legal foundation for Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. (New York Times story)

It came in August 1964 with a brief encounter in the Gulf of Tonkin, the waters off the coast of North Vietnam where the U.S. Navy posted warships loaded with electronic eavesdropping equipment enabling them to monitor North Vietnamese military operations and provide intelligence to CIA-trained South Vietnamese commandos. One of these ships, the U.S.S. Maddox was reportedly fired on by gunboats from North Vietnam.

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964) Photo: Arnold Newman, White House Press Office

The reported attack came in the midst of LBJ’s 1964 campaign against hawkish Republican Barry Goldwater. President Johnson felt the incident called for a tough response and had the Navy send the Maddox and a second destroyer, the Turner Joy, back into the Gulf of Tonkin. A radar man on the Turner Joy saw some blips, and that boat opened fire. On the Maddox, there were also reports of incoming torpedoes, and the Maddox began to fire. There was never any confirmation that either ship had actually been attacked. Later, the radar blips would be attributed to weather conditions and jittery nerves among the crew.

According to Stanley Karnow’s Vietnam: A History,

“Even Johnson privately expressed doubts only a few days after the second attack supposedly took place, confiding to an aide, ‘Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.’”

Johnson ordered an air strike against North Vietnam and then called for passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. This legislation gave the president the authority to “take all necessary measures” to repel attacks against U.S. forces and to “prevent further aggression.” The resolution not only gave Johnson the powers he needed to increase American commitment to Vietnam, but allowed him to blunt Goldwater’s accusations that Johnson was “timid before Communism.”

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed the House unanimously after only forty minutes of debate. In the Senate, there were only two voices in opposition. What Congress did not know was that the resolution had been drafted several months before the Tonkin incident took place. In June 1964, on LBJ’s orders, according to journalist-historian Tim Weiner,

“Bill Bundy, the assistant secretary of state for the Far East, brother of the national security adviser, and a veteran CIA analyst, had drawn up a war resolution to be sent to Congress when the moment was ripe.” (Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA, p. 280)

Congress, which has sole constitutional authority to declare war, had handed that power over to Johnson, who was not a bit reluctant to use it. One of the senators who voted against the Tonkin Resolution, Oregon’s Wayne Morse, later said,

“I believe that history will record that we have made a great mistake in subverting and circumventing the Constitution.”

After the vote, Walt Rostow, an adviser to Lyndon Johnson, remarked,

“We don’t know what happened, but it had the desired result.”

In January 1971, Congress repealed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution as popular opinion grew against a continued U.S. military involvement in Vietnam

Since Vietnam, United States military actions have taken place as part of United Nations’ actions, in the context of joint congressional resolutions, or within the confines of the War Powers Resolution (also known as the War Powers Act) that was passed in 1973, over the objections (and veto) of President Richard Nixon.”

The War Powers Resolution came as a direct reaction to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Congress sought to avoid another military conflict where it had little input.

“The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the Limits of Presidential Power” National Constitution Center

In 2005, the National Security Agency (NSA) issued a report reviewing the Tonkin incident in which it said “no attack had happened.” (Weiner, p. 280)

The National Endowment for the Humanities website Edsitement offers teaching resources on Tonkin and the escalation of the Vietnam War.

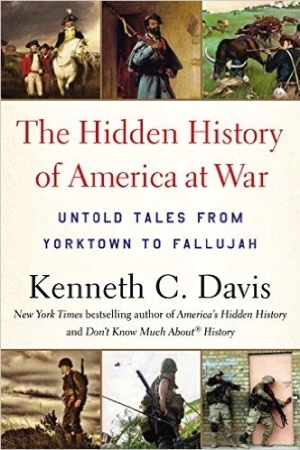

Read more about Vietnam, LBJ and his administration in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents. The Vietnam War and the Tonkin Resolution are also covered in a chapter on the Tet offensive of 1968 in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

May 13, 2019

151 Years of the Divisive & Partisan History of “Memorial Day”

MEMORIAL DAY -MONDAY MAY 27, 2019

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Photo: Arlington National Cemetery) This memorial was created after the great losses of World War I.

(Revise of 2015 post)

It is a well-established fact that Americans like to argue. And we do. Mays or Mantle. A Caddy or a Lincoln. And, of course, abolition, abortion, and guns.

But a debate over Memorial Day –and more specifically where and how it began? America’s most solemn holiday should be free of rancor. But it never has been.

The heated arguments over removing the Confederate flag and monuments to heroes and soldiers of the Confederacy in New Orleans and provide examples and reminders of the birth of Memorial Day.

In the Korean War, the U.S. military was integrated. (Source: Library of Congress)

Waterloo, New York claimed that the holiday originated there with a parade and decoration of the graves of fallen soldiers in 1866. But according to the Veterans Administration, at least 25 places stake a claim to the birth of Memorial Day. Among the pack are Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, which says it was first in 1864.( “Many Claim to Be Memorial Day Birthplace” )

And Charleston, South Carolina, according to historian David Blight, points to a parade of emancipated children in May 1865 who decorated the graves of fallen Union soldiers whose remains were moved from a racetrack to a proper cemetery.

But the passions cut deeper than pride of place.

Born 151 years ago out of the Civil War’s catastrophic death toll as “Decoration Day,” Memorial Day is a day for honoring our nation’s war dead. A veteran of the Mexican War and the Civil War, John A. Logan, a Congressman and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, set the first somber commemoration on May 30, 1868, in Arlington Cemetery, the sacred space wrested from property once belonging to Robert E. Lee’s family.( When Memorial Day was No Picnic by James M. McPherson.) The Grand Army of the Republic was a powerful fraternal organization formed of Civil War Union veterans.

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

From its inception, Decoration Day (later Memorial Day) was linked to “Yankee” losses in the cause of emancipation. Calling for the first formal Decoration Day, Union General John Logan wrote, “Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains…”

In other words, Logan’s first Decoration Day was divisive— a partisan affair, organized by northerners.

In 1871, Frederick Douglass gave a Memorial Day speech in Arlington that focused on this division:

We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.

I am no minister of malice. I would not strike the fallen. I would not repel the repentant; but may my “right hand forget her cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth,” if I forget the difference between the parties to that terrible, protracted, and bloody conflict.

But the question remains: what inspired Logan to call for this rite of decorating soldier’s graves with fresh flowers?

The simple answer is—his wife.

While visiting Petersburg, Virginia – which fell to General Grant 150 years ago in 1865 after a year-long, deadly siege – Mary Logan learned about the city’s women who had formed a Ladies’ Memorial Association. Their aim was to show admiration “…for those who died defending homes and loved ones.”

Choosing June 9th, the anniversary of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” in 1864, a teacher had taken her students to the city’s cemetery to decorate the graves of the fallen. General Logan’s wife wrote to him about the practice. Soon after, he ordered a day of remembrance.

The teacher and her students, it is worth noting, had placed flowers and flags on both Union and Confederate graves.

As America wages its partisan wars at full pitch, this may be a lesson for us all.

More resources at the New York Times Topics archive of Memorial Day articles

The story of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” is told in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR (Now in paperback)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

February 19, 2019

Don’t Know Much About® Executive Order 9066

On this date- February 19, 1942 – a different kind of infamy

Dorothea Lange

In this 1942 Dorothea Lange photograph from the book “Impounded,” a family in Hayward, Calif., awaits an evacuation bus.

Franklin D. Roosevelt famously told Americans when he was inaugurated in 1933:

The only thing we have to fear is fear itself

But on February 19, 1942 –a little more than two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor— President Roosevelt allowed America’s fear to provoke him into an action regarded among his worst mistakes. He issued Executive Order 9066.

The result of this Executive Order was the policy of “relocating” some 120,000 Japanese Americans, and a smaller number of German and Italian Americans, into “internment camps.”

I have written about the subject of the internment of the Japanese American population in the past including one on photojournalist Dorothea Lange, and Ansel Adams, who also documented the period.

Photo: (National Park Service, Jeffery Burton, photographer

Among these resources is a site devoted to the War Relocation Camps –a Teaching With Historic Places Lesson Plan from the National Park Service called “When Fear Was Stronger than Justice.”

February 12, 2019

It is NOT Presidents Day. Or President’s Day. Or Even Presidents’ Day.

So What Day Is it After All?

Okay. We all do it. It’s printed on calendars and posted in bank windows. We mistakenly call the third Monday in February Presidents Day, in part because of all those commercials in which George Washington swings his legendary ax and “Rail-splitter” Abe Lincoln hoists his ax to chop down prices on everything from mattresses and linens to SUVs.

But, this February holiday is officially still George Washington’s Birthday –federally speaking that is.

The official designation of the federal holiday observed on the third Monday of February was, and still is, Washington’s Birthday.

I wrote My Project About Presidents in 3rd Grade when I was 9. Even then I was asking questions about history and presidents

But Washington’s Birthday has become widely known as Presidents Day (or President’s Day, or Presidents’ Day). The popular usage and confusion resulted from the merging of what had been two widely celebrated Presidential birthdays in February —Lincoln’s on February 12th, which was never a federal holiday– and Washington’s on February 22, which was.

Created under the Uniform Holiday Act of 1968, which gave us three-day weekend Monday holidays, the federal holiday on the third Monday in February is technically still Washington’s Birthday. But here’s the rub: the holiday can never land on Washington’s true birthday because the latest date it can fall is February 21, as it did in 2011.

There is a wealth of information about the First President at his home Mount Vernon.

Washington’s Tomb — Mt. Vernon (Photo credit Kenneth C. Davis 2010)

Read More About the creation of the Presidency, Washington, his life and administration in DON’T KNOW MUCH ABOUT® THE AMERICAN PRESIDENTS. Washington’s role in the American Revolution is highlighted Chapter One of THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR.

And George Washington’s role as a slaveowner is fully explored in IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives.

The Hidden History of America At War (paperback)

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

January 30, 2019

Who Said It? (1/30/2019)

Franklin D. Roosevelt, First Inaugural Address (March 4, 1933)

I am certain that my fellow Americans expect that on my induction into the Presidency I will address them with a candor and a decision which the present situation of our Nation impels. This is preeminently the time to speak the truth, the whole truth, frankly and boldly. Nor need we shrink from honestly facing conditions in our country today. This great Nation will endure as it has endured, will revive and will prosper. So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself–nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance. In every dark hour of our national life a leadership of frankness and vigor has met with that understanding and support of the people themselves which is essential to victory. I am convinced that you will again give that support to leadership in these critical days.

Source: Avalon Project

Franklin. D. Roosevelt was both on January 30, 1882. More here

FDR had the Flu

Of the many what-ifs of history, this is a big one.

In September 1918, Franklin D. Roosevelt -then the Assistant Secretary of the Navy- was carried off the troopship Leviathan by stretcher. He had just inspected U.S. troops in Europe and, either before leaving France or on board the transport, he came down with the Spanish Flu –then sweeping the warring world.

Leviathan, a confiscated German ship was converted into a troop carrier during World War I. The largest passenger ship in the world at the time, it was used to transport thousands of troops, many of whom fell sick during the Spanish Flu pandemic.

The fifth cousin of the 26th President, Theodore Roosevelt, FDR was taken to his mother’s Manhattan apartment. He had the flu and was deathly ill.

What if… Franklin D. Roosevelt had not survived this bout of the Spanish Flu?

Roosevelt did survive. Previously a New York State senator, he returned to politics and was the unsuccessful Democratic candidate for Vice President in 1920.

In August 1921, Roosevelt fell ill with what was thought to be polio, which left his legs crippled. (Recently, it has been suggested he might have had a different illness.) Remaining active in Democratic politics, FDR continued his recuperation, learning to walk with the use of braces and a cane. He made sure that he was not seen using a wheelchair in public.

Despite this disability, Franklin D. Roosevelt went on to be elected Governor of New York in 1928. After the Great Depression began, he ran for a second term and addressed the economic crisis with relief packages which President Hoover resisted on the national level.

So, first of all, let me assert my firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is…fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.

In 1932, Roosevelt ran against the incumbent Hoover. With the nation in the depths of the Great Depression crisis, the worst economic downturn in American history. He had promised Americans a “New Deal” and started a series of federal relief programs to get the American economy moving again. Despite the continuing national depression, he was reelected in 1936 by a landslide and again in 1940, becoming the first U.S. President to win a third term in office.

By then his attention had turned to foreign affairs and the threat posed in Europe by Hitler and Mussolini and in Asia by Japan. He led the United States into World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

Born on January 30, 1882, Franklin D. Roosvelt died on April 12, 1945. Here is a chronology of FDR’s life as part of his New York Times obituary.

More resources on Roosevelt’s life can be found at his Presidential Library and Museum.