Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 42

March 23, 2020

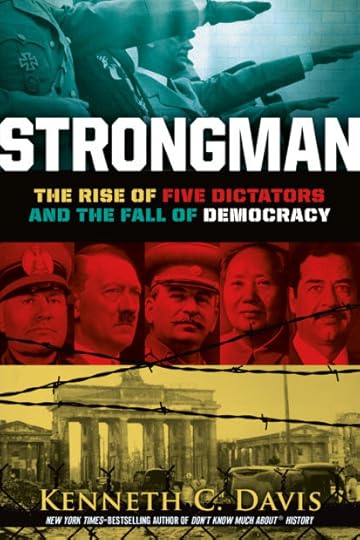

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

In October 2020, my new book, STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy, will be published (Holt Books).

In it, I recount the story of the rise to power of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world. In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy (October 2020)

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

–Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

–Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

–Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of your young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

–Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

Watch for more news about STRONGMAN here in the coming months.

March 16, 2020

Who Said It? (3/16/20)

James Madison, writing anonymously, in “A Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments” (June 1785)

James Madison by Thomas Sully (Library of Congress)

Because we hold it for a fundamental and undeniable truth, “that Religion or the duty which we owe to our Creator and the manner of discharging it, can be directed only by reason and conviction, not by force or violence.” The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate. This right is in its nature an unalienable right. It is unalienable, because the opinions of men, depending only on the evidence contemplated by their own minds cannot follow the dictates of other men: It is unalienable also, because what is here a right towards men, is a duty towards the Creator. It is the duty of every man to render to the Creator such homage and such only as he believes to be acceptable to him.

Who does not see that the same authority which can establish Christianity, in exclusion of all other Religions, may establish with the same ease any particular sect of Christians, in exclusion of all other Sects? that the same authority which can force a citizen to contribute three pence only of his property for the support of any one establishment, may force him to conform to any other establishment in all cases whatsoever?

“A Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments,” anonymously authored by James Madison and published on or about June 20, 1785, argues against a resolution by the House of Delegates, adopted on November 11, 1784, to levy a so-called General Assessment to benefit all Christian sects, including dissenters against the established Church of England. The resolution excited such opposition, and petitions like Madison’s such support, that Madison was emboldened to reintroduce Thomas Jefferson‘s Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom, which passed the General Assembly on January 16, 1786.

Source: Encyclopedia Virginia

Don’t Know Much About® Mr. Madison

March 16 marks the anniversary of the birth of America’s fourth President, James Madison, also known as “The Father of the Constitution.”

While small in stature, and sometimes overshadowed by his more famous Virginian predecessors, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, Madison is generally considered one of the greatest of the Founding Fathers for the breadth and influence of his contributions. Like many of the Founders, Madison had reservations about slavery as a contradiction to this ideals, but did little to end the institution. He hoped that slavery would end after the foreign trade was abolished and thought that enslaved African-Americans should be emancipated and returned to Africa.

Montpelier, home of James Madison (Photo: Kenneth C. Davis, 2010)

James Madison was born on March 16, 1751 in Port Conway, Virginia. The son of a tobacco planter, he chose the unusual course of going north to study at the College of New Jersey (now Princeton). There he came under the influence of the college President, John Witherspoon, a future signer of the Declaration of Independence, and made a friend of fellow student, young Aaron Burr, son of the College’s founder.

Returning to Virginia, Madison became involved in patriot politics and became a close colleague of his neighbor Thomas Jefferson, serving as Jefferson’s adviser and confidant during the war years while Jefferson was Governor of Virginia.

In 1794, he married the widow Dolley Payne Todd, having been formally introduced by his college friend Aaron Burr.

A few Madison Highlights–

•Secured passage of the Virginia Act for Establishing Religious Freedom (1786), an act that is a cornerstone of religious freedom in America. As part of that effort, he wrote the influential Memorial and Remonstrance Against Religious Assessments. (I discuss the “Remonstrance” in my article “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance” in the October 2010 Smithsonian.)

•Was the moving force behind the Constitutional Convention and was one of the principal authors of the Constitution. Madison’s support of the electoral system is laid out in this essay by Yale professor Akhil Reed Amar “The Troubling Reason the Electoral College Exists.”

•With Alexander Hamilton and John Jay was one of the authors of The Federalist Papers, arguments in favor of the ratification of the Constitution

•Was principal author of the Bill of Rights, which he originally thought unnecessary

Following ratification of the Constitution, Madison was a member of the House of Representatives from Virginia and a powerful Congressional ally of George Washington.

•Drafted the first version of Washington’s Farewell Address

•Supervised the Louisiana Purchase as Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of State

•Presided over the ill-prepared nation during the War of 1812, the “second war of independence”

I believe there are more instances of the abridgment of the freedom of the people by gradual and silent encroachments of those in power than by violent and sudden usurpations. –June 16, 1788

Madison’s grave at Montpelier (Author photo 2010)

Madison died on June 28, 1836 at Montpelier, at age 85. Enslaved servant Paul Jennings was at his bedside and later recalled in a memoir that Madison died, “as quietly as the snuff of a candle goes out.”

James Madison is buried at Montpelier.

The story of Paul Jennings, who was enslaved by Madison and wrote a memoir of working as a servant in the White House, is told in my recent book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

LINKS:

The White House brief biography of James Madison

The Library of Congress Resource Collection on James Madison.

Madison’s Major Papers and Inaugural Addresses can be found at the Avalon Project of the Yale Law School.

February 29, 2020

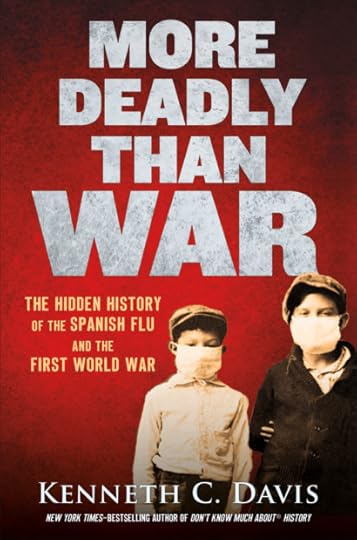

“Have Americans Forgotten the History of this Deadly Flu?”

Members of the St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps on duty on five ambulances during the 1918 flu pandemic. Via Library of Congress

This is from a PBS interview that ran in November 2018 about the impact of the Spanish Flu and the possibility of another pandemic outbreak. This is the subject of my book More Deadly Than War. As I said at the time,

Could this happen again? The answer is, of course. And I’m sure there are people at the CDC who probably have nightmares about this. But we are much better prepared than we were 100 years ago. We would possibly have a vaccine that would work against such a virus, if it were identified and produced in massive numbers quickly enough.

We have erected enormous guardrails around the world through international cooperation, the World Health Organization, perhaps one of the most effective parts of the United Nations. Those guardrails are weakened when we deny science, when we ignore sound medical advice for short-term political considerations.

Read more of the interview here:

“In autumn of 1918, the largest military offensive in American history was raging on Europe’s Western Front. The battle concluded on Nov. 11, 1918, when the Armistice with Germany was signed, ending what was known as the Great War.

But more U.S. soldiers died of disease (63,114), primarily from the Spanish flu, than in combat (53,402).

Overall, 675,000 Americans were killed by the Spanish flu. This number surpasses the total of U.S. soldiers killed in World War I, World War II, the Korean War and Vietnam War combined. Current day estimates put the death toll from the 1918-1919 outbreak of the Spanish flu between 80 to 100 million worldwide.”

February 19, 2020

Don’t Know Much About® Executive Order 9066

(Post revised 2/19/2020)

On this date- February 19, 1942 – a different kind of infamy

Dorothea Lange

In this 1942 Dorothea Lange photograph from the book “Impounded,” a family in Hayward, Calif., awaits an evacuation bus.

Franklin D. Roosevelt famously told Americans when he was inaugurated in 1933:

The only thing we have to fear is fear itself

But on February 19, 1942 –a little more than two months after the attack on Pearl Harbor— President Roosevelt allowed America’s fear to provoke him into an action regarded among his worst mistakes. He issued Executive Order 9066.

The result of this Executive Order was the policy of “relocating” some 120,000 Japanese Americans, and a smaller number of German and Italian Americans, into “internment camps.”

The National Constitution Center offers an excellent overview of the order and its impact.

I have written about the subject of the internment of the Japanese American population in the past including one on photojournalist Dorothea Lange, and Ansel Adams, who also documented the period.

Photo: (National Park Service, Jeffery Burton, photographer

Among these resources is a site devoted to the War Relocation Camps –a Teaching With Historic Places Lesson Plan from the National Park Service called “When Fear Was Stronger than Justice.”

February 18, 2020

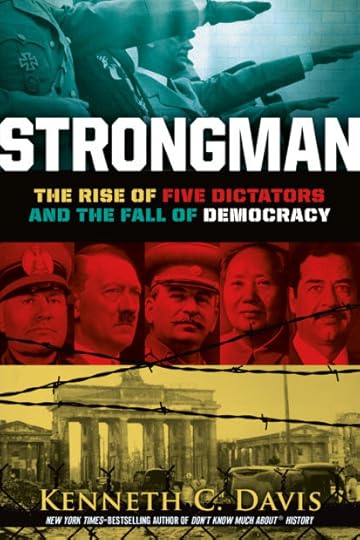

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

In October 2020, my new book, STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy, will be published (Holt Books).

In it, I recount the story of the rise to power of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world. In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy (October 2020)

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

–Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

–Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Watch for more news about STRONGMAN here in the coming months.

February 11, 2020

Don’t Know Much About® Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday

February 12 used to mean something special — Abraham Lincoln’s Birthday. It was never a national holiday but it was pretty important when I was a kid and we got the day off from school in my hometown.

The Uniform Holidays Act in 1971 changed that by creating Washington’s Birthday as a federal holiday on the third Monday in February. It is NOT officially “Presidents Day.”

But it is still a good excuse to talk about Abraham Lincoln, especially since his real birthday is on the calendar.

“Honest Abe.” “The Railsplitter.” “The Great Emancipator.” You know some of the basics and the legends. But check out this video to learn some of things you may not know, but should, about the 16th President.

Here’s a link to the Lincoln Birthplace National Park

This link is to the Emancipation Proclamation page at the National Archives.

February 5, 2020

Who Said It? (Annual Address Edition)

George Washington, First Annual Address to Congress (January 8, 1790)

Nor am I less persuaded that you will agree with me in opinion that there is nothing which can better deserve your patronage than the promotion of science and literature. Knowledge is in every country the surest basis of public happiness. In one in which the measures of government receive their impressions so immediately from the sense of the community as in ours it is proportionably essential.

Complete Text and Source: The American Presidency Project, UC Santa Barbara

Under the terms of the Constitution, Washington delivered this message to Congress in person. It would later be called the State of the Union address.

Read more from Washington’s Mount Vernon Plantation.

February 2, 2020

Who Said It?

Thomas Paine, “The Crisis” (December 23, 1776)

Portrait of Thomas Paine (1792) National Portrait Gallery

[While Paine’s birthday is listed in some sources as January 29, 1736, others cite a date of February 9, 1737. This reflects the change in calendars in Great Britain and American colonies. The January date is “Old Style.”]THESE are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value.

Note: Most of these Who Said It posts have focused on the words of American presidents. This quote from Thomas Paine is a shift to quotes from other key figures in American History. Learn more about Thomas Paine’s life at the Thomas Paine Society.

January 23, 2020

Who Said It? (1/23/2020)

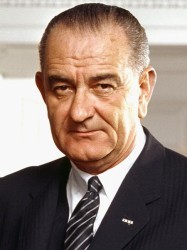

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964)

(Photo: Arnold Newman, WHite House Press Office)

The collection of poll taxes in national elections was prohibited on January 23, 1964, with ratification of the Twenty-Fourth Amendment to the Constitution. Passage of the amendment affected voting in Alabama, Mississippi, Arkansas, Texas, and Virginia.

At ceremonies formalizing ratification in February, President Lyndon Johnson noted that by abolishing the poll tax the American people:

…reaffirmed the simple but unbreakable theme of this Republic. Nothing is so valuable as liberty, and nothing is so necessary to liberty as the freedom to vote without bans or barriers…There can be no one too poor to vote.

Source Library of Congress