Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 38

June 27, 2020

Whatever Became of 56 Signers (7th in series)

(Updated 6/27/2020; Part 7 in a series that begins here. Part 6 Here)

NOTE: YES following the entry means the Signer enslaved people; No means he did not.

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

A tavern owner’s son. Two of America’s wealthiest men –both named Morris. And the first to die. The next five signers in this series.

-Thomas McKean (Delaware) Son of a Pennsylvania farmer-tavern owner, McKean was a self educated, 42-year-old attorney turned politician at the time of the signing (although he did not sign in 1776).

in 1768 he was elected to the American Philosophical Society, a distinguished intellectual society founded by Benjamin Franklin. In 1769 McKean became a trustee of the Academy of Newark, the successor to Allison’s school at New London. He received honorary degrees from Princeton in 1781, Dartmouth in 1782 and Pennsylvania in 1785. Source: The Society of Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration.

A vigorous patriot, he held offices in both his native Pennsylvania and Delaware and was a key supporter of the Declaration. When another delegate from Delaware was absent and the state might vote against independence, McKean sent a horse and rider to collect fellow delegate Caesar Rodney and bring him back to vote —an 80 mile ride in a storm. There is some dispute about when he actually signed but it was after January 1777.

McKean and his family were pursued by the British but never captured. A vocal advocate of the Constitution, he served in many state posts, including governor of Pennsylvania, and prospered after the war. He died in 1817 at age 83. YES

–Arthur Middleton (South Carolina) A 34 year old plantation owner, at the signing, replaced his father –thought too conservative — in Congress. Educated in England, he became active in patriot politics. One of the few delegates to serve in the wartime militia, he was captured in Charleston in 1780, along with Thomas Heyward (Post #4) and Rutledge, two other South Carolina signers. Although his home had been destroyed he was released by the British and returned to Congress in 1781. After the war he returned to his plantation where he died at age 44 in 1787. YES

–Lewis Morris (New York) Another of the wealthy sons of prominent New York families in the state’s delegation, Morris was a 50 year old land owner with large holdings in what is now the Bronx in New York City. Although his home was assaulted by British troops during the war, it was attacked and severely damaged because of its value, not because he was a signer. Morris led troops of the militia during the vote in July, but then led the New York delegation in later signing the Declaration, making it unanimous. Morris rebuilt the family home and land holdings after the war and was a leader with Alexander Hamilton in ratification of the Constitution. He died in 1798, aged 71 and his former plantation is known today as the Morrisania section of the Bronx. YES

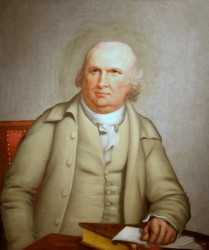

Oil painting of Robert Morris by Robert Pine (c. 1785)

–Robert Morris (Pennsylvania) (No relation to Lewis Morris above.) One of the wealthiest individuals in America, he was a 42 year old Philadelphia merchant and speculator when he signed. Born in Liverpool, he had come to America and made a fortune as a merchant, becoming the “Financier of the Revolution.” Accused of profiteering during the war, he was attacked in the Philadelphia home of fellow signer James Wilson. A delegate to the Constitutional Convention in 1787, he declined to serve as Washington’s secretary of Treasury, recommending Alexander Hamilton instead. He later became a Senator. But he lost his fortune through land speculation and was bankrupted and put in debtor’s prison. He died in poverty and relative obscurity in 1806, aged 72. YES

–John Morton (Pennsylvania) A farm boy turned surveyor, he was 52 at the time of the signing. He has two key distinctions: his vote pushed Pennsylvania into the pro-independence camp and then he was first signer to die. He fell ill with tuberculosis in 1777 and died at about age 52, leaving his farm and enslaved people to his wife and children who had to flee from a British attack. YES

June 26, 2020

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (6th in a series)

[Post updated 6/26/2020]

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

(Sixth in a series. Previous post #5 here. Note: The Yes after a named means the Signer enslaved people; No means he did not. The first post is here.)

Wealthy planters, and a couple of very wealthy New York merchants.

-Richard Henry Lee (Virginia) A 41-year-old planter from a prominent Virginia family –his younger brother Francis Lightfoot (See previous post) was also there– Lee deserves more acclaim than he usually gets. A “great orator,” said John Adams, Lee introduced the resolution for independence. He left Congress to attend to state business in Virginia and didn’t vote for the resolution or the Declaration, which he signed later in the summer of 1776.

Richard Henry Lee National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of Duncan Lee and his son, Gavin Dunbar Lee

He was one of the few signers to actually serve with a Virginia militia unit. He remained in politics after the war, becoming a vocal opponent of the Constitution but an advocate for the Bill of Rights. He was elected to the U.S. Senate but resigned in ill health and died at age 62 in 1794. YES

–Francis Lewis (New York) A native of Wales, he was a 63-year-old merchant at the time of the signing, a key supporter of George Washington, but was instructed not to vote for the Declaration by New York. He then signed in August. During the war, his wife was imprisoned by the British and died shortly after her release, leaving Lewis grief-stricken. He died in 1802 at age 89, was buried in an unmarked grave at Manhattan’s Trinity Church, and now, curious New Yorkers will know why there is a Francis Lewis Boulevard in Queens. YES

–Philip Livingston (New York) The 60-year-old member of one of New York’s wealthiest families, with an estate of 160,000 acres on the Hudson River, he was a merchant who favored the patriot cause. But like many New Yorkers, he was more moderate and cautious about declaring independence and was absent when the entire delegation abstained from the vote. He signed in August. (Robert Livingston, a cousin and member of the Declaration draft committee, was also absent from the vote and never signed the Declaration).

“General Washington and his officers met at Philip’s residence in Brooklyn Heights after their defeat in the battle of Long Island, and decided to evacuate the island. The British subsequently used Philip’s Duke Street home as a barracks, and his Brooklyn Heights residence as a Royal Navy hospital. As the British occupied New York City, Philip and his family fled to Kingston, NY where he maintained another residence. Later, the British burned the city of Kingston to the ground as they did Robert R. Livingston’s mansion, Clermont, across the Hudson River.” (Source: Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Although he sold some of his property to support the war effort, his family continued to amass large land holdings in upstate New York. In poor health, he died at age 62 in 1778, when Congress was forced to evacuate Philadelphia and move to York, Pa. YES

–Thomas Lynch, Jr. (South Carolina) At 27, the second youngest signer (after Edward Rutledge also of South Carolina), he was lawyer and the son of a delegate. When his father, a wealthy planter, suffered a stroke, the younger Lynch was sent to Congress. (His father was unable to vote or sign.) Both left for home in poor health and the elder Lynch died en route. Lynch Jr. and his wife later sailed for the West Indies in the hope of regaining his health but both died at sea in 1779 when their ship was lost in a storm. Among the youngest signers, he was the youngest signer to die at age 30. YES

June 25, 2020

Whatever Became of 56 Signers (5th in a series)

[Post updated 6/25/2020]

Jefferson’s Desk on which he drafted the Declaration (Image: American Museum of History/Smithsonian)

(This is the fifth in a series. The previous post #4 is here. The first post is linked here.)

Slave trader turned early abolitionist. Flag designer. “First President.” Member of a Virginia dynasty. And the Author.

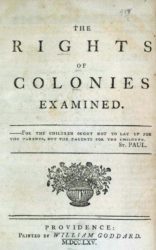

-Stephen Hopkins (Rhode Island) Second oldest delegate after Franklin, Hopkins was 69 years old at the signing. A merchant, he had been Rhode Island’s colonial governor but was an outspoken advocate of independence having written a document entitled, The Rights of the Colonies Examined in 1764.

“Rights of the Colonies Examined” (1765 :Source Wikimedia Commons

A partner of the wealthy Brown brothers who were involved in the slave trade –Newport was a key northern slavery port– he enslaved several people. The role of Stephen Hopkins, his brother Esek -captain of a slave ship- and the Brown brothers as enslavers and the founding of what became Brown University is detailed in a report commissioned by Brown called Slavery and Justice.

But in 1774, he secured passage of law prohibiting the slave trade in Rhode Island, one of the first anti-slavery laws in the colonies and he began freeing some but not all of the people he enslaved. In ill health, he retired from politics and public life and died in 1785 at age 78. YES

-Francis Hopkinson (New Jersey) Like Franklin and Jefferson, Hopkinson was a man of many talents, a 38-year-old attorney and musician at the time of the signing. He was the son of the founder –with Franklin– of the University of Pennsylvania and was among the school’s first graduates. Though long overlooked, he has more recently gotten his due as the designer of the “Stars and Stripes.” The claim is based on Hopkinson submitting a bill for his work on the flag and requesting “a quarter cask of the public wine” in payment. He was already on the Congressional payroll so the request was refused. While his home was ransacked during the war, he emerged relatively unscathed and later became a Federal judge before his death in 1791 at 53. YES

-Samuel Huntington (Connecticut) An apprenticed barrel-maker who became a successful attorney, he was a 45 year old politician at the time of the signing, having resigned his post as “King’s Attorney.” His true distinction is serving as “President of the United States in Congress Assembled” when the Articles of Confederation were adopted –making him the “First President,” sort of. Others have staked that claim as well. He served in a variety of national and state posts, including being the sitting governor of Connecticut at his death in 1796 at age 64. NO

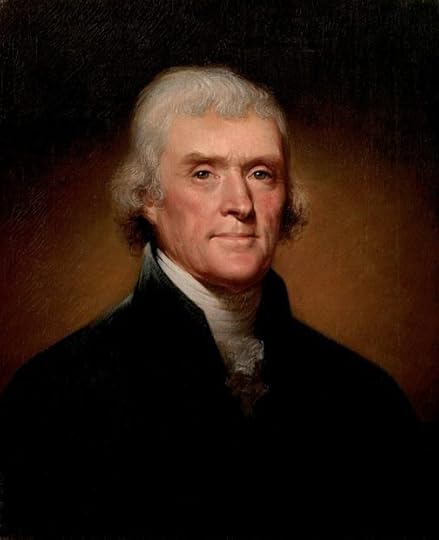

–Thomas Jefferson (Virginia) 33-year-old planter, scientist, writer, and lawyer. You know most of the rest. But Jefferson’s wartime service as Virginia’s governor is sometimes overlooked. In 1781, he was Virginia’s governor when the British attacked the state, including forces led by Benedict Arnold. Jefferson fled and was later investigated by the state legislature but no charges were filed. People enslaved by Jefferson were captured by the British and were being held in Yorktown during the siege in September-October 1781 and were later returned to Jefferson by George Washington.

Thomas Jefferson’s Grave Marker at Monticello (Author photo)

He died, like John Adams, on the 50th anniversary of the adoption –July 4, 1826. See the Monticello site for more information. YES

–Francis Lightfoot Lee (Virginia) A member of the state’s prominent planter family, he was 41 years old at the signing, the quiet brother of Richard Henry Lee, who offered the first resolution calling for independence in June 1776. After the war, he was a prominent advocate of the new Constitution, unlike his more visible older brother. He left the national scene and died at age 62 in 1797. YES

June 24, 2020

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (4th in a series)

[Post revised 6/24/2020]

Fair Copy of the Draft of the Declaration of Independence (Source New York Public Library)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Part 4 in a series that begins here. Previous post #3 is here.

Father and great-grandfather of presidents. A simple farmer. A Quaker workaholic. More lawyers. The next five signers, in alphabetical order: (Yes following the entry means slaveholder; No means not a slaveholder.)

-Benjamin Harrison V (Virginia) A member of the Virginia aristocracy, he was a well-to-do planter, around 50 years old at the the signing.

On June 7, 1776, Benjamin Harrison was chosen to introduce fellow Virginian Richard Henry Lee whose resolution called for independence from England. He was selected to read Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence to the assembled delegates on July 1… [Source: Berkeley Plantation]

Besides his role in the July 2 and 4 votes in Philadelphia, he is mostly distinguished as being the father of 9th president William Henry Harrison and great-grandfather of namesake Benjamin Harrison, the 23rd president.

Although his famed Berkeley Plantation on the James River was attacked and partially burned by British forces led by the traitor Benedict Arnold, it clearly survived the war. So did Harrison, who went on to serve three terms as governor of Virginia before his death in 1791 at age 65. YES

-John Hart (New Jersey) Described as a well-meaning “Jersey” farmer with little education, Hart was a 65 year old planter at the time of the signing, and devoted to the patriot cause. Although supposedly hounded by the British during the war, he was later able to entertain General Washington and allow 12,000 troops to camp in his fields in 1778. He died of kidney stones in 1779, aged 68. YES

–Joseph Hewes (North Carolina) Born in New Jersey, he moved to North Carolina and was a 46 year old Quaker merchant at the signing. At first a reluctant patriot, he broke with the Quakers over the possibility of a violent rebellion and was considered a key influence in Congress by John Adams. His shipping experience was significant enough for him to be described as the first “secretary of the Navy,” responsible for getting his friend John Paul Jones a commission. Working relentlessly for the Congress, Hewes fell sick and died in 1779 at age 49 and was deeply mourned by his Congressional colleagues. YES

-Thomas Heyward, Jr. (South Carolina) Son of a wealthy planter, he was a 30 year old lawyer at the signing. Heyward counts as one of the few signers actually captured by the British, who then took his enslaved people, apparently shipping them to bondage in the West Indies. Initially paroled (released under an agreement), he was later taken aboard a prison ship and then held in St. Augustine, Florida under a form of house arrest until released in a prisoner exchange. While a hostage, he is credited with writing verses to a song called “God Save the Thirteen States.” He dabbled in politics after the war, but focused on rebuilding his family plantation where he died at 63 in 1809. YES

-William Hooper (North Carolina) Born in Boston, he was a 34-year-old attorney who had moved South at the signing. He missed the key July vote but returned to sign the Declaration in August. Hooper was one of the signers who suffered losses during the war when the British invaders evacuating the Wilmington, North Carolina area destroyed his home. He later pressed for ratification of the Constitution but lacked popularity in his adopted state and, suffering from a variety of illnesses, including malaria, died in 1790 at age 48. YES

June 23, 2020

Whatever Became Of…56 Signers? (3d in series)

[Post revised June 23, 2020]

Fair Copy of the Draft of the Declaration of Independence (Source New York Public Library)

Part 3 in a series of posts about the fates of the signers of the Declaration of Independence. A printer, a politician with a notable name, a duelist, a Connecticut Yankee, and the most famous signature in U.S. history.

A Yes after their names means they enslaved people; No means they did not.

-Benjamin Franklin (Pennsylvania) America’s most famous man in 1776, Franklin was 70 years old at the time of the signing. Printer, publisher, writer, scientist, diplomat, philosopher –he was the embodiment of the Enlightenment ideal. A member of the draft committee that produced the Declaration, Franklin was a central figure in the independence vote and then helped the war effort by winning crucial French support for the America cause.

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; gift of the Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation https://npg.si.edu/object/npg_NPG.87....

But he lost no Fortune, reportedly tripling his wealth during the conflict. Franklin returned to the scene of the Declaration’s passage in 1787 to help draft the Constitution. When he died at age 84 in 1790, his funeral was attended by a crowd equal to Philadelphia’s population at the time. Read more on Franklin at this National Park Service site. YES

–Elbridge Gerry (Massachusetts) A 32-year-old merchant from Marblehead, Gerry (pronounced with a hard G like Gary) is much more famous for later dividing Massachusetts into oddly-shaped voting districts as the state’s governor. A cartoonist compared the districts to a salamander and the word “gerry-mandering” was born.

“The Gerry-mander,” political cartoon “The Gerry-mander,” political cartoon by Elkanah Tisdale, Boston Gazette, 1812. © North Wind Picture Archives via Britannica https://www.britannica.com/topic/gerr...

Though he voted for independence, Gerry was not present to sign in August, signing later in the fall of 1776. He profited from the war and later joined the Massachusetts delegation to the Constitutional convention in 1787, although he refused to sign the Constitution. He became James Madison’s second vice president in 1813, but died in office in 1814 at age 70. NO

–Button Gwinnett (Georgia) An English-born plantation owner and merchant, he was 41 at the time of the signing. And didn’t last much longer. A political argument with a Georgia general led to a duel in which Gwinnett was mortally wounded. He died in 1777 at age 42, the second of the signers to die. (John Morton of Pennsylvania was first.) YES

–Lyman Hall (Georgia) A Connecticut Yankee Congregational minister and physician transplanted to Georgia plantation owner, Hall was 52 years old at the signing. A vocal patriot when Georgia was far more hesitant about independence, he first came to Philadelphia as a nonvoting delegate. Hall’s plantation was destroyed during the war during the punishing British campaigns in the South. He later served as Georgia’s governor, dying at age 66 in 1790. YES

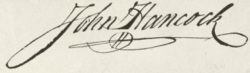

–John Hancock (Massachusetts) Born into a poor parson’s family in Lexington (National Parks Service site), Hancock was sent to live with a wealthy uncle when his father died. He inherited his uncle’s shipping business and was one of America’s wealthiest men by the time he was thirty. A patriot leader in Boston, it was Hancock and Samuel Adams who the British sought to capture on that April 1775 night when the war began.

Cropped from Image:Us_declaration_independence.jpg and enhanced slightly by Tim Packer Image:John_Hancock_Signature_DOI.PNG. Source: Wikimedia Commons

President of the Continental Congress when independence was declared, he was 39 at the time of the signing. The out-sized signature on the document cemented his fame in American lore. Elected Governor of Massachusetts in 1780,

Hancock lived a conspicuously opulent life in his mansion crowning Beacon Hill. The citizenry still had weapons and were accustomed to fighting the taxes of remote governments. Recognizing the stirrings of revolution and suffering from reoccurring gout, Hancock resigned the governorship until the resistance, which took the form of Shay’s Rebellion, was put down.

After the war,

Governor Hancock continued to be reelected annually with victory margins frequently well above eighty percent. He died in office in 1793 and was succeeded by his friend, Lieutenant Governor Samuel Adams. (Source: Commonwealth of Massachusetts)

YES

June 22, 2020

Whatever Became Of…56 Signers? (2d in a series)

(Post revised and updated 6-22-2020)

Fair Copy of the Draft of the Declaration of Independence (Source New York Public Library)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Part 2 of a series that begins here. (A YES denotes an enslaver or slave trader; NO means the person did not enslave people.)

Here are the next five Signers of the Declaration, continuing in alphabetical order:

–Samuel Chase (Maryland) A 35 year old attorney, Chase is among those signers who didn’t vote on July 4; he signed the later printed version in August. Accused of wartime profiteering but never tried or convicted, he later went broke from business speculating and settled into law practice. President George Washington appointed him to the Supreme Court, and Chase became the first justice to be impeached –although he was acquitted.

The failure of the Senate to convict allowed Chase to return to the Supreme Court and serve 6 more years as an associate justice. More importantly, the acquittal deterred the House of Representatives from using impeachment as a partisan political tool.

Read more: Samuel Chase – The Samuel Chase Impeachment Trial – Democratic, House, Jefferson, and Jury – JRank Articles https://law.jrank.org/pages/5151/Chase-Samuel-Samuel-Chase-Impeachment-Trial.html#ixzz6Q6M6venl

Chase returned to the Supreme Court and died of a heart attack in 1811 at age 70. YES Learn more about Impeachment history here.

-Abraham Clark (New Jersey) An attorney, 50 years old at the signing, Clark had two sons who were captured and imprisoned during the war; one on the notorious British prison ship Jersey and the other in a New York jail cell. Clark served in Congress on and off and opposed the Constitution’s ratification until the Bill of Rights was added. He died in 1794 at age 68. YES

–George Clymer (Pennsylvania) A 37 year old merchant the time of the signing, Clymer was a well-heeled patriot leader who helped fund the American war effort. He was also elected to Congress after the July 2 independence vote, signing the Declaration on August 2. He belongs to an elite group who signed both the Declaration and the Constitution. (The others were Roger Sherman of Conn,; George Read of Del.; and Benjamin Franklin, Robert Morris and James Wilson, all of PA.) He continued to prosper after the war and died in 1813 at age 74. NO

-William Ellery (Rhode Island) A modestly successful merchant turned attorney, aged 48 at the signing, Ellery replaced an earlier Rhode Island delegate who died of smallpox in Philadelphia. (Smallpox killed more Americans than the war did during the Revolution.) A dedicated member of Congress during the war years, Ellery saw his home burned by the British although it is thought unlikely they knew it was the home of a Signer. An abolitionist, he was rewarded after the war by President Washington with the lucrative post of collector for the port of Newport which he held for three decades. He died in 1829, aged 92, second in longevity among signers after Carroll. NO

-William Floyd (New York) At the signing, a 41 year old land speculator born on Long Island, New York, Floyd abstained from the July 2 independence vote with the rest of the New York delegation, but is thought to be the first New Yorker to sign the Declaration on August 2. Reports that his home on Fire Island was destroyed by the British were exaggerated, although it was used as a stable and barracks by the occupying Redcoats. (It is now part of a Fire Island National Park.) Floyd served in the first Congress before moving to western New York where he owned massive land tracts and where he died at age 86 in 1821. YES

In the Shadow of Liberty: The Hidden History of Slavery, Four Presidents, and Five Black Lives

Who Said It? (6.22.2020)

Thomas Jefferson, “discussing the fight over the establishment of one form of Christianity in the U.S. to Dr. Benjamin Rush, September 23, 1800.” Peterson, Merrill, ed. Jefferson: Writings. New York: Literary Classics of the U.S., Viking Press, c1984, p. 1082 Source: Monticello)

June 20, 2020

“Lives, Fortunes, Sacred Honor:” Whatever Became Of 56 Signers? (1st in a series)

This is the first in a series of posts about the men who signed the Declaration of Independence and what became of them. Most of these men are obscure to many Americans and they have also been mythologized in some online forums. Their role before, during and after July 4, 1776 is significant. One focus of the series is to show which of these men enslaved people or otherwise participated in the slave trade.

They pledged:

“... our Lives, our Fortunes, and our Sacred Honor.”

Then what happened?

The Grand Flag of the Union, the “first American flag,” originally raised in 1775 and later by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

This is an updated repost of a series about the 56 Signers of the Declaration of Independence. Included in this list is a simple guide to those Signers who enslaved people. A Yes means they enslaved people; a No means they did not. Slavery existed in all thirteen of the future states and at least 40 of the 56 signers enslaved people or were involved in the slave trade and

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

Those strong words concluded the Declaration of Independence when it was adopted by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776.

There is little question that men who signed that document were putting their lives at risk. The identity and fates of a handful of those Signers is well-known. Two future presidents — Adams and Jefferson— and America’s most famous man, Benjamin Franklin, were on the Committee that drafted the document.

But the names and fortunes of many of the other signers, including the most visible, John Hancock, are more obscure. In the days leading up to Independence Day, I will offer a thumbnail sketch of each of the Signers in alphabetical order. Some prospered and thrived; some did not: How many of those Signers actually paid with their Lives, Fortunes, and Sacred Honor?

–John Adams (Massachusetts) Aged 40 when he signed, he went on to become the first vice president and second president of the United States. By 1790, Adams was convinced that his place in the history to be written would be diminished.

“The history of our Revolution will be one continued lie from one end to the other,” he wrote fellow Founder Benjamin Rush in 1790.

“The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington. That Franklin electrified him with his rod –and thenceforward these two conducted all the policies, negotiations, legislatures, and war.”

Adams died on the 50th anniversary of the Declaration in 1826 at age 90. (Jefferson died that same day) NO

–Samuel Adams (Mass.) Older cousin to John, Samuel Adams was 53 at the signing. He went on to a career in state politics, initially refused to sign the Constitution because it lacked a Bill of Rights, and was governor of Massachusetts. He died in 1803 at 81. NO

–Josiah Bartlett (New Hampshire) Inspiring the name of the fictional president of West Wing fame on TV, Bartlett was a physician, aged 46 at the time of the signing. He helped ratify the Constitution in his home state, giving the document the necessary nine states to become the law of the land. Elected senator he chose to remain in New Hampshire as governor. Three of his sons and other descendants also became physicians. He died in 1795 at age 65. YES

–Carter Braxton (Virginia) A 39-year-old plantation owner, Braxton was looking to invest in the slave trade before the Revolution. Initially reluctant about independence, he helped fund the rebellion and lost a considerable fortune during the war — not because he was a signer, but because of shipping losses suffered during the war itself. He later served in the Virginia legislature and died in 1797 at age 61, far less wealthy than he had been, but also far from impoverished. YES

–Charles Carroll of Carrollton (Maryland) A plantation owner, 38 years old and one of America’s wealthiest men at the signing, Carroll was the only Roman Catholic signer and the last signer to die. With hundreds of enslaved people on his properties, Carroll considered freeing some of them before his death and later introduced a bill for gradual abolition in Maryland, which had no chance of passage. At age ninety-one, he laid the cornerstone of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad as a member of its board of directors. He died in 1832 at age 95. YES

Update: Carroll’s cousin was John Carroll, a Jesuit priest, first Roman Catholic bishop in the United States, and a founder of Georgetown College. The New York Times has reported how, in 1838, Georgetown sold 272 enslaved people to keep the college financially afloat.

June 11, 2020

Don’t Know Much About® the Tulsa Massacre

It was called a “riot.” But it was really a massacre — one of the bloodiest in American history.

This material is adapted from Don’t Know Much About® History: Everything You Need to Know About American History but Never Learned (pages 325-327).

In the early 1920s, Tulsa, Oklahoma, was a boisterous postwar boom town, getting rich quick on oil that had recently been discovered there. It was a place where the postwar Ku Klux Klan recruiters found fertile grounds. The isolationist mood, or the America First movement also called nativism, was also flourishing.

In the popular mood of the country, America was white and Christian, and it was going to stay that way. On May 30, 1921, when a teen-aged Black shoe shiner was arrested for assaulting a white girl in an elevator, the publisher of the local paper—eager to win a local circulation war—published a front-page that witnesses have claimed said, “To Lynch Negro Tonight.” (No copy of the paper was ever found, even in newspaper archives.)

It was a familiar story in the Deep South of that era—a Black man accused of sexually assaulting a white woman. Soon after the paper hit the streets, white crowds began to gather outside the courthouse where the accused shoe shiner, Dick Rowland, was being held. (Rowland was eventually released when the woman did not press charges.)

Blacks from the Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood, some of them recently discharged war veterans, also began to descend on the courthouse to protect Rowland from being lynched. Shots were fired and soon the wholesale destruction of an entire community began in hellish force. A mob of more than 10,000 whites, fully backed by the white police force, went wild. It was called a riot but it was a massacre, or in modern parlance there is a better term—“ethnic cleansing.” It lasted over three days.

As historian Tim Madigan put it in his book on Tulsa, The Burning,

“It soon became evident that whites would settle for nothing less than scorched earth. They would not be satisfied to kill negroes, or to arrest them. They would also try to destroy every vestige of black prosperity.”

Soon white women were looting Black homes, filling shopping bags. White men carrying gasoline set fire to the Greenwood neighborhood.

An overview of the aftermath of the Tulsa race massacre in 1921. (Greenwood Cultural Center) via Washington Post

When it was over, there were many dead Blacks, some of them dumped into mass graves, and their neighborhood was in cinders, with more than 1,200 homes burned. Insurance companies later refused to pay fire claims, invoking a riot exemption. To add to the crime, the story disappeared from local history. Even local newspaper files were eventually cleaned out to remove evidence of the incident.

“Tulsa Searches for Mass Graves” (Washington Post, October 23, 2019)

For decades, the massacre was hushed up, kept alive only by oral traditions of a few survivors. Only after nearly eighty years of silence did Tulsa and the Oklahoma legislature come to grips with the past. Historians looking into the city’s deadly massacre believe that close to 300 people died during the violence. In 2000, the “Tulsa Race Riot Commission,” a panel investigating the incident, recommended reparations be paid to the survivors of what is still considered the nation’s bloodiest incident of racial violence.

“No legislative action was ever taken on the recommendation, and the commission had no power to force legislation. In April 2002 a private religious charity, the Tulsa Metropolitan Ministry, paid a total of $28,000 to the survivors, a little more than $200 each, using funds raised from private donations.” (Source: Encyclopedia Britannica)

Don’t Know Much About® the Tulsa “Race Riot”

It was called a “riot.” But it was really a massacre — one of the bloodiest “race riots” in American history.

This material is adapted from Don’t Know Much About® History: Everything You Need to Know About American History but Never Learned (pages 325-327).

In the early 1920s, Tulsa, Oklahoma, was a boisterous postwar boom town, getting rich quick on oil that had recently been discovered there. It was a place where the postwar Ku Klux Klan recruiters found fertile grounds. The isolationist mood, or the America First movement also called nativism, was also flourishing.

In the popular mood of the country, America was white and Christian, and it was going to stay that way. On May 30, 1921, when a teen-aged Black shoe shiner was arrested for assaulting a white girl in an elevator, the publisher of the local paper—eager to win a local circulation war—published a front-page that witnesses have claimed said, “To Lynch Negro Tonight.” (No copy of the paper was ever found, even in newspaper archives.)

It was a familiar story in the Deep South of that era—a Black man accused of sexually assaulting a white woman. Soon after the paper hit the streets, white crowds began to gather outside the courthouse where the accused shoe shiner, Dick Rowland, was being held. (Rowland was eventually released when the woman did not press charges.)

Blacks from the Tulsa neighborhood of Greenwood, some of them recently discharged war veterans, also began to descend on the courthouse to protect Rowland from being lynched. Shots were fired and soon the wholesale destruction of an entire community began in hellish force. A mob of more than 10,000 whites, fully backed by the white police force, went wild. It was called a riot but it was a massacre, or in modern parlance there is a better term—“ethnic cleansing.” It lasted over three days.

As historian Tim Madigan put it in his book on Tulsa, The Burning,

“It soon became evident that whites would settle for nothing less than scorched earth. They would not be satisfied to kill negroes, or to arrest them. They would also try to destroy every vestige of black prosperity.”

Soon white women were looting Black homes, filling shopping bags. White men carrying gasoline set fire to the Greenwood neighborhood.

An overview of the aftermath of the Tulsa race massacre in 1921. (Greenwood Cultural Center) via Washington Post

When it was over, there were many dead Blacks, some of them dumped into mass graves, and their neighborhood was in cinders, with more than 1,200 homes burned. Insurance companies later refused to pay fire claims, invoking a riot exemption. To add to the crime, the story disappeared from local history. Even local newspaper files were eventually cleaned out to remove evidence of the incident.

“Tulsa Searches for Mass Graves” (Washington Post, October 23, 2019)

For decades, the riot and killings were hushed up, kept alive only by oral traditions of a few survivors. Only after nearly eighty years of silence did Tulsa and the Oklahoma legislature come to grips with the past. Historians looking into the city’s deadly riot believe that close to 300 people died during the violence. In 2000, the Tulsa Race Riot Commission, a panel investigating the incident, recommended reparations be paid to the survivors of what is still considered the nation’s bloodiest race riot.

“No legislative action was ever taken on the recommendation, and the commission had no power to force legislation. In April 2002 a private religious charity, the Tulsa Metropolitan Ministry, paid a total of $28,000 to the survivors, a little more than $200 each, using funds raised from private donations.” (Source: Encyclopedia Britannica)