Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 40

May 13, 2020

Who Said It? (5/13/20)

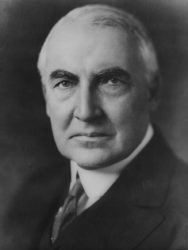

Warren G. Harding (May 14, 1920)

Senator Warren G. Harding (1920) Image Wikipedia

America’s present need is not heroics, but healing; not nostrums, but normalcy; not revolution, but restoration; not agitation, but adjustment; not surgery, but serenity; not the dramatic, but the dispassionate; not experiment, but equipoise; not submergence in internationality, but sustainment in triumphant nationality.

My best judgment of America’s needs is to steady down, to get squarely on our feet, to make sure of the right path. Let’s get out of the fevered delirium of war, with the hallucination that all the money in the world is to be made in the madness of war and the wildness of its aftermath. Let us stop to consider that tranquillity at home is more precious than peace abroad, and that both our good fortune and our eminence are dependent on the normal forward stride of all the American people. . . .

Source: Teaching American History

Following World War I and the Spanish flu pandemic, Senator Warren G. Harding (Ohio-Rep.) ran for president on a platform of a “return to normalcy.” He won the 1920 presidential election in a popular and electoral landslide, the first incumbent Senator to be elected president. His presidency was marred by the Teapot Dome scandal and other corruption in his cabinet which emerged fully after his death in office. Harding died while on a national tour in San Francisco on August 2, 1923. He was succeeded by Calvin Coolidge.

Resources on Harding from the Library of Congress

May 11, 2020

The 1918 Pandemic That Killed Millions (Matter of Fact video)

The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919 was the most deadly outbreak of disease in modern times. It was completely connected to the last year of World War I. And it has some important lessons today as the world confronts another deadly pandemic. This short video looks at the history of one pandemic while we live through another.

May 8, 2020

The first “Mother’s Day”-Some Hidden History

[Updated older post]

Let me be among the first to say Happy Mother’s Day. Spouses, partners, and children everywhere: Don’t forget.

But amidst the brunches, flower-giving, and chocolate samplers, there is a story of another “Mother’s Day” that is worth remembering this weekend.

Julia Ward Howe, a prominent abolitionist best known for writing “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” published what became known as the “Mother’s Day Proclamation,” originally called “An Appeal to Womanhood Throughout the World.”

Julia Ward Howe (1907) Source: Library of Congress

In 1870, Howe wrote:

Our husbands shall not come to us reeking with carnage, for caresses and applause. Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy, and patience. . . . From the bosom of the devastated earth a voice goes up with our own. It says, Disarm, Disarm! The sword of murder is not the balance of justice! Blood does not wipe out dishonor nor violence indicate possession.

Source and Complete Text: Library of Congress

Howe’s international call for mothers to become the voice of pacifism found few takers. Even among like-minded women, there was greater urgency over the suffrage question. Her passionate campaign for a “Mother’s Day for Peace” begun in 1872 fell by the wayside.

Mother’s Day, as we know it, is not the invention of Hallmark; it started in 1912 through the efforts of West Virginia’s Anna Jarvis to create a holiday honoring all mothers for their sacrifice and to assist mothers who needed help.

Today, Mother’s Day is largely a commercial bonanza — flowers, chocolates and greeting cards. Is it possible to truly honor Howe’s version of Mother’s Day and work towards her original vision of Mother’s Day?

If only we remember the history behind the holiday and what she thought it should be.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Who Said It? (5/8/2020)

President Harry S. Truman May 8, 1945 V-E Day. It was a good day to celebrate his birthday.

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

THE PRESIDENT. Well, I want to start off by reading you a little statement here. I want you to understand, at the very beginning, that this press conference is held with the understanding that any and all information given you here is for release at 9 a.m. this morning, eastern war time. There should be no indication of the news given here, or speculation about it, either in the press or on the radio before 9 o’clock this morning.

The radio-my radio remarks, and telegrams of congratulation to the Allied military leaders, are for release at the same time. Mr. Daniels has copies of my remarks, available for you in the lobby as you go out, and also one or two releases here.

[1.] Now, for your benefit, because you won’t get a chance to listen over the radio, I am going to read you the proclamation, and the principal remarks. It won’t take but 7 minutes, so you needn’t be uneasy. You have plenty of time. [Laughter]

“This is a solemn but glorious hour. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly all over Europe.”

Source: Harry S. Truman: “The President’s News Conference on V-E Day,” May 8, 1945. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

Harry S. Truman was born on May 8, 1884. Read more about him in this post, Don’t Know Much About® Harry Truman

Learn more about Truman at the Truman Presidential Library

Who Said It? (5/8/2018)

President Harry S. Truman May 8, 1945 V-E Day. It was a good day to celebrate his birthday.

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

THE PRESIDENT. Well, I want to start off by reading you a little statement here. I want you to understand, at the very beginning, that this press conference is held with the understanding that any and all information given you here is for release at 9 a.m. this morning, eastern war time. There should be no indication of the news given here, or speculation about it, either in the press or on the radio before 9 o’clock this morning.

The radio-my radio remarks, and telegrams of congratulation to the Allied military leaders, are for release at the same time. Mr. Daniels has copies of my remarks, available for you in the lobby as you go out, and also one or two releases here.

[1.] Now, for your benefit, because you won’t get a chance to listen over the radio, I am going to read you the proclamation, and the principal remarks. It won’t take but 7 minutes, so you needn’t be uneasy. You have plenty of time. [Laughter]

“This is a solemn but glorious hour. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly all over Europe.”

Source: Harry S. Truman: “The President’s News Conference on V-E Day,” May 8, 1945. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

Harry S. Truman was born on May 8, 1884. Read more about him in this post, Don’t Know Much About® Harry Truman

Learn more about Truman at the Truman Presidential Library

Don’t Know Much About® Harry S. Truman

Harry Truman “Gave’ Em Hell.” I gave him a A. Born on May 8, 1884, the 33rd President of the United States.

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

It was on his birthday in 1945 that Truman was able to tell Americans that the war in Europe was over with the surrender of Germany.

THIS IS a solemn but a glorious hour. I only wish that Franklin D. Roosevelt had lived to witness this day. General Eisenhower informs me that the forces of Germany have surrendered to the United Nations. The flags of freedom fly over all Europe. For this victory, we join in offering our thanks to the Providence which has guided and sustained us through the dark days of adversity.

Described as “a minor national figure with a pedestrian background,” Truman was a World War I veteran and a Senator from Missouri when Franklin D. Roosevelt chose him to become his running mate in the 1944 election. Truman became vice president when FDR won his fourth term and then took office on April 12, 1945 when FDR died.

When he took office, Truman had been largely left “out of the loop” by Roosevelt as World War II entered its final months. Truman did not know of the existence of the “Manhattan Project” and the development of the atomic bomb until he became president. Then he had to make the decision to use it against the Japanese.

Fast Facts

•Truman was a member of the Sons of the Revolution and the Sons of Confederate Veterans

•He wanted to attend West Point but poor eyesight kept him out. He enlisted in the Missouri National Guard and served as the commander of an artillery battery in World War I.

•Before entering politics, he was a farmer, bank clerk, insurance salesman and owner of a failed haberdashery store.

•As president he once threatened to punch the nose of a newspaper critic who had given his daughter a poor review after her debut singing recital. Margaret Truman went on to greater fame as a mystery novelist, beginning with Murder in the White House published in 1980.

•After Grover Cleveland, Truman is the only president who did not attend college. He attended law school briefly but dropped out.

After the end of World War II, Truman had to shift America’s attention to the new “Cold War” with the Soviet Union and his policies of “containment” and the Marshall Plan to rebuild war-torn Europe were hallmarks of his presidency.

Harry S. Truman died on December 26, 1972.

The Truman Library and Museum is located in Independence, Missouri

Read more about Truman, his life and administration in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents. Truman is also featured in the Berlin Battle chapter of The Hidden History of America at War.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

May 2, 2020

STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy

In October 2020, my new book, STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy, will be published (Preorder from Holt Books) (An audiobook edition will be released by Penguin Random House)

In it, I recount the story of the rise to power of five of the most deadly dictators of the 20th century — Mussolini, Hitler, Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Saddam Hussein.

In addition to telling how these men took unlimited power, brought one-party rule to their nations, and were responsible for the deaths of millions of people, the book offers a brief history of Democracy and discusses the present threat to democratic institutions around the world. In a time when Democracy is under assault across the globe, it is more important than ever to understand how a Strongman takes power and how quickly democracy can vanish –even as millions cheer its death.

Strongman: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy (October 2020)

ADVANCE PRAISE FOR STRONGMAN

“I found myself engrossed in it from beginning to end. I could not help admiring Davis’s ability to explain complex ideas in readable prose that never once discounted the intelligence of your young readers. It is very much a book for our time.”

—Sam Wineburg, Margaret Jacks Professor of Education & History, Stanford University, author of Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone).

“Strongman is a book that is both deeply researched and deeply felt, both an alarming warning and a galvanizing call to action, both daunting and necessary to read and discuss.”

—Cynthia Levinson, author of Fault Lines in the Constitution: The Framers, Their Fights, and the Flaws That Affect Us Today

“A wake-up call to democracies like ours: we are not immune to despots . . . Strongman demonstrates that democracy is not permanent, unless it is collectively upheld. This book shakes that immortality narrative.”

—Jessica Ellison, President of the Minnesota Council for the Social Studies; Teacher Education Specialist, Minnesota Historical Society

Rarely does a history book take such an unflinching look at our common future, where the very presence of democracy is less than certain; even rarer is a history book in which the author’s moral convictions incite young readers to civic engagement; rarest of all, a history book as urgent, as impassioned, and as timely as Kenneth C. Davis’ Strongman.

—Eugene Yelchin, author of the Newbery Honor book Breaking Stalin’s Nose.

Watch for more news about STRONGMAN here in the coming months.

May 1, 2020

Who is “An Enemy of the People?”

We have reached our Dr. Stockman moment.

Henrik Ibsen by Gustava Borgen (public Domain via Wikimedia)

In Ibsen’s classic drama, An Enemy of the People, Dr. Thomas Stockman has discovered that the waters in his town’s famed spa are poisoning the guests. He pleads with his brother, the Mayor, to close the lucrative attraction. But Mayor Peter Stockman refuses to shut down and repair the toxic baths.

“Have you taken the trouble to consider what your proposed alterations would cost?” the Mayor asks his brother. “And do you suppose anyone would come near the place after it had got about that the water was dangerous?”[1]

And there it is. Ibsen brings us to that place where economic health trumps public health.

Sound familiar? It should. Because we face a similar conflict today. A president and his administration are pushing to “reopen” the economy despite express warnings from medical experts about the perils of premature action.[2]

We have been down this road before. This is not the first time that the common good and the bottom line have faced off. In the midst of one pandemic, we need only look to the history of the 1918 pandemic, a story told in my book More Deadly Than War.

What was later called the Spanish flu emerged in March 1918, blossoming into an epidemic on army bases where young Americans were training for Europe’s trenches. After slacking in summertime, the outbreak returned in a second wave, even more swift and lethal, hitting American ports like Boston in September 1918. Striking down soldiers and sailors by the thousands, it jumped from the military to the civilian population. Seeing “bodies stacked like cordwood,” army doctors wondered if they were witnessing a new plague. The Spanish flu was carried to other ports and military bases, including those near Philadelphia.

But to Philadelphia’s civil authorities, it was “just the flu.” And Philadelphia was planning a parade – a grandiose show of patriotism and pride to promote the sale of Liberty Loans. These war bonds were marketed through an intense nationwide propaganda campaign that made buying these bonds an act of allegiance. Woe to those “slackers” who didn’t “do their part.”

Read Philadelphia Threw a WWI Parade That Gave Thousands of Onlookers the Flu

As Philadelphia planned its spectacle, the city’s director of public health knew better. A gynecologist, and an appointee loyal to Philadelphia’s notoriously corrupt political machine, Dr. Wilmer Krusen was warned to cancel the parade. But Dr. Krusen allowed the show to go on. He assured the public that recent military deaths were from “old-fashioned influenza or grip.”[3] His words were a harbinger of the president’s in January. “It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine.”[4]

It wasn’t. As the parade got underway on September 28, 1918, some 200,000 people jammed Philadelphia’s main street, packed eight deep on the sidewalks. Within seventy-two hours of that parade, every bed in Philadelphia’s hospitals was filled.[5]

On October 3, most public spaces –schools, churches, theaters, and pool halls –were officially closed.[6] The delayed lockdown to “flatten the curve” was too little, too late for many in the City of Brotherly Love. Within weeks, more than 12,000 people died in Philadelphia before the epidemic crested there.

Dr. Krusen was aware of the risks posed when he allowed the parade to step off. But he was answering to political and economic concerns, much like the Mayor in Ibsen’s play, and so many economists and administration officials echoing the president’s call to reopen the economy.

History is replete with Dr. Krusen’s counterparts—those scientists and other people who dared challenge authority. Take Giordano Bruno for example. Born in 1548, Bruno became a priest and a learned mathematician. But he was also a free thinker and, in 1584, published his concept that the sun, not the earth, was at the center of Creation.

Bruno was arrested and tried for this and other heresies during the Inquisition. Refusing to recant, the rebellious priest was sentenced as an impenitent heretic on papal orders. In February 1600, he was taken to the Campo de’ Fiori, an open market in Rome, his tongue in a gag, and burned alive.

Today, there is a statue honoring Giordano Bruno in the Campo de’ Fiori. There are no statues of Dr. Krusen. In modern parlance, Bruno was an “Upstander,” Dr. Krusen a “Collaborator.”

Close up of the statue of Giordano Bruno in the Camp de Fiori, Rome (Public Domain Wikipedia Commons)

Giordano Bruno would not serve a master who demanded that he deny the science that contradicted faith. He served the truth. Dr. Stockman refused to serve a master who placed profits over life and was ultimately branded “an enemy of the people.” Dr. Krusen chose instead to answer to his political masters.

This is the essential question now facing both American leadership and every individual. If we are to survive the current coronavirus, we need to carefully choose and serve a worthy master.

TEACHERS: If you would like a virtual visit to discuss this topic or any of my work, please get in touch with me. Here’s the link: Contact page.

[1] Henrik Ibsen, An Enemy of the People, Act II.

[2] https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation...

[3] John M. Barry, The Great Influenza, p. 204

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/op...

[5] Gina Kolata, Flu, p. 20.

[6] Barry, p. 220.

April 30, 2020

Don’t Know Much About® George Washington’s Fashion Statement

(Original post of 2014 updated 4/30/2020)

The American Presidency began 231 years ago when George Washington took the oath of office on April 30, 1789.

For the occasion, Washington wore a suit made in Connecticut. He hoped it would become “unfashionable for a gentleman to appear in any other dress” than one of American manufacture.

(Excerpted from Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents)

He took the oath of office on April 30, 1789, a cool, clear Thursday morning. One similarity to modern inaugurations was the big crowd. A large throng of New Yorkers filled the streets of what is now the city’s financial district, then the center of a city that was much smaller than modern Manhattan.

Washington arrived by carriage to what had previously been New York’s City Hall, given a “face-lift” by Pierre L’Enfant, future designer of the nation’s capital city. The entire government operated out of this single building, renamed Federal Hall. Washington managed more people on his Mount Vernon plantation than worked for the new national government.

For the inauguration he was dressed in a brown suit, white silk stockings, and shoes with silver buckles, and he carried a sword. The suit cloth was made in a mill in Hartford, Connecticut, and Washington had said that he hoped it would soon be “unfashionable for a gentleman to appear in any other dress” than one of American manufacture.

Standing on the second- floor balcony, the “Father of Our Country” took the oath of office on a Masonic Bible. Legend has it that he kissed the Bible and said, “So help me God”— words not required by the Constitution.

But there is no contemporary report of Washington saying those words. On the contrary, one eyewitness account, by the French minister, Comte de Moustier, recounts the full text of the oath without mentioning the Bible kiss or the “So help me God” line. Washington’s use of the words was not reported until late in the nineteenth century. (The demythologizing of this piece of presidential history occasioned a suit by notable atheist Michael Newdow, who sued unsuccessfully in 2009 to keep all mention of God out of the inauguration of Barack Obama.)

What followed was the first Inaugural Address, written by James Madison. Here Washington spoke freely of “the propitious smiles of Heaven”— a divine hand in guiding the nation’s fate. These heavenly references raise the perennial question of faith in the early republic. But, as Ron Chernow writes in Washington, “Washington refrained from endorsing any particular form of religion.”

Here is the transcript of Washington’s first inaugural address from the National Archives. The site of the first inauguration is Federal Hall National Memorial.

Read more about Washington, his life and his presidency in Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents and Don’t Know Much About® History.

April 25, 2020

Who Said It? (4/25/20)

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

Address Before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society

Milwaukee, Wisconsin

September 30, 1859

It is said an Eastern monarch once charged his wise men to invent him a sentence, to be ever in view, and which should be true and appropriate in all times and situations. They presented him the words: “And this, too, shall pass away.” How much it expresses! How chastening in the hour of pride! — how consoling in the depths of affliction! “And this, too, shall pass away.” And yet let us hope it is not quite true. Let us hope, rather, that by the best cultivation of the physical world, beneath and around us; and the intellectual and moral world within us, we shall secure an individual, social, and political prosperity and happiness, whose course shall be onward and upward, and which, while the earth endures, shall not pass away.

Source: Abraham Lincoln Online