Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 39

June 7, 2020

Juneteenth: The “Other” Independence Day

(Revise of a post first published June 2015)

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free…” –General Gordon Granger, June 19, 1865

WEDNESDAY JUNE 19 is a day to mark “Juneteenth” –a holiday celebrating emancipation at the end of the Civil War.

I believe that we have two histories in this country — one white, one black — and they have largely been separate and unequal. The story of Juneteenth is a perfect example of how one of these histories has largely been hidden when we teach American history.

Now more than ever, it is time to fix that.

Foods on the Juneteenth altar include beets, strawberries, watermelon, yams and hibiscus tea, as well as a plate of black-eyed peas and cornbread. Credit Jim Wilson/The New York Times

For centuries, slavery was the dark stain on America’s soul, the deep contradiction to the nation’s founding ideals of “Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness” and “All men are created equal.”

When Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, he took a huge step toward erasing that stain. But the full force of his proclamation would not be realized until June 19, 1865—Juneteenth, as it was called by enslaved people in Texas freed that day.

“Juneteenth: Our Other Independence Day” My article in Smithsonian (June 15, 2011)

The official Juneteenth Committee in East Woods Park, Austin, Texas on June 19, 1900. (Courtesy Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

“SOME two months after Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered on April 9, 1865, effectively ending the Civil War, Maj. Gen. Gordon Granger steamed into the port of Galveston, Tex. With 1,800 Union soldiers, including a contingent of United States Colored Troops, Granger was there to establish martial law over the westernmost state in the defeated Confederacy.

On June 19, two days after his arrival and 150 years ago today, Granger stood on the balcony of a building in downtown Galveston and read General Order No. 3 to the assembled crowd below. “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free,” he pronounced.” (New York Times June 19, 2015)

Read more of the complete story of Juneteenth in my New York Times Op-ed, “Juneteenth is for Everyone”. The celebration of the the holiday and its traditions of foods is highlighted in this New York Times article, “Hot Links and Red Drinks”

The question of how we teach and talk about enslavement is also the subject of my recent article in Social Education, the Journal of the National Council for the Social Studies. (NCSS). Read: The American Contradiction: Conceived in Liberty, Born in Shackles.

June 5, 2020

Who Said It?

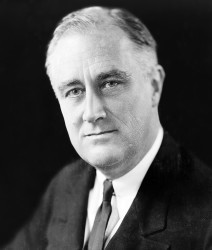

On the night of June 6, 1944, President Roosevelt went on national radio to discuss the invasion of Normandy — D-Day — with the American people.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “D-Day Prayer” (June 6, 1944)

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “D-Day Prayer” (June 6, 1944)

Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.

Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest-until the victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and flame. Men’s souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

His address took the form of this prayer. (Full text from Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum)

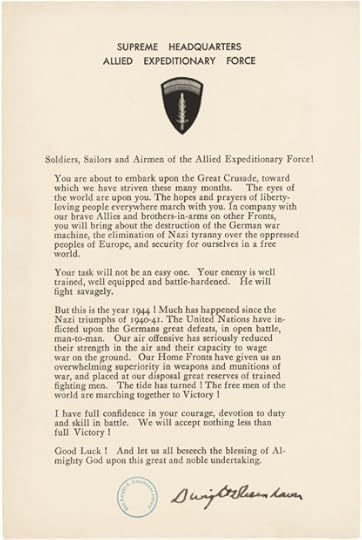

The day before, future president Dwight D. Eisenhower, addressed the troops of the Allied Expeditionary Force and told them,

The hopes and prayer of liberty-loving people everywhere march with you.

00763_2003_001.tif

Don’t Know Much About® D-Day

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, “D-Day Prayer” in an announcement to the nation of the invasion of Normandy (June 6, 1944)

Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1933

My fellow Americans: Last night, when I spoke with you about the fall of Rome, I knew at that moment that troops of the United States and our allies were crossing the Channel in another and greater operation. It has come to pass with success thus far.

And so, in this poignant hour, I ask you to join with me in prayer:

Almighty God: Our sons, pride of our Nation, this day have set upon a mighty endeavor, a struggle to preserve our Republic, our religion, and our civilization, and to set free a suffering humanity.

Lead them straight and true; give strength to their arms, stoutness to their hearts, steadfastness in their faith.

They will need Thy blessings. Their road will be long and hard. For the enemy is strong. He may hurl back our forces. Success may not come with rushing speed, but we shall return again and again; and we know that by Thy grace, and by the righteousness of our cause, our sons will triumph.

They will be sore tried, by night and by day, without rest-until the victory is won. The darkness will be rent by noise and flame. Men’s souls will be shaken with the violences of war.

Franklin Roosevelt’s D-Day Prayer Source: Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and Museum

“Into the Jaws of Death – U.S. Troops wading through water and Nazi gunfire” by Robert F. Sergeant (National Archives)

In the largest amphibian assault in history, Allied armies crossed the English Channel to land on five beaches in Normandy in northern France. The invasion force involved 700 ships, 4,000 landing craft, 10,000 planes, and some 176,000 Allied troops from twelve countries. The allied forces were commanded by future President, Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The day was chaotic, brutal and bloody.

Steven Spielberg’s World War II epic, Saving Private Ryan, brought the reality of combat home to millions, but many moviegoers did not know which battle the film depicted, or when and why it happened. The assault, code-named Operation Overlord, occurred June 6, 1944, against Hitler’s Germany.

By the of the day on June 6, 1944, the allies had taken all five beaches that had been targeted. The combined allied losses on that day have been recently stated at 4,415 dead, according to the National D-Day Memorial.

The German army did not formally surrender until May 7, 1945. May 8, 1945 was declared V.E. (Victory in Europe) Day.

More D-Day resources can be found at the FDR Library and Museum

Read more about FDR’s life and administration and World War II in Don’t Know Much About® History and Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

June 1, 2020

Don’t Know Much About® the Bible

The Devil can scripture for his own purpose.

–Shakespeare, The Merchant of Venice

Throughout history, the Bible has been used to justify many arguments. Often those biblical citations are mistaken, taken out of context, based on a mistranslation –or simply misused. These myths and misconceptions about what is in the Bible led me to write Don’t Know Much About® the Bible.

In American history, the Bible was cited to both justify slavery and call for its abolition. For centuries, slavers pointed to a passage in the book of Genesis to justify the cruel, murderous enslavement of millions of Africans. It is a part of the story of Noah that is not usually told in Sunday school.

After building the ark, loading the animals two by two, and weathering the Flood, Noah and his family reach dry land. Noah begins to plant and grows some grapes to make wine:

20 And Noah began to be an husbandman, and he planted a vineyard:

21 And he drank of the wine, and was drunken; and he was uncovered within his tent.

22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without.

23 And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness.

24 And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him.

25 And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren.

26 And he said, Blessed be the Lord God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

27 God shall enlarge Japheth, and he shall dwell in the tents of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant.

–Genesis 9:20-27 King James Version

The passage is a bit garbled. But the “curse of Ham” was used to justify the enslavement of people of African ancestry, who were believed to be descendants of Ham, through his son Canaan. This theory was widely held during the eighteenth to twentieth centuries to justify both slavery and the racist notion of the inferiority of Blacks, and added to the many biblical references used by Christians to justify enslavement.

Gradually, other Christians argued that to enslave another human was a basic contradiction of Jesus’s teachings, including the Christian version of the “Golden Rule”:

Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them: for this is the law and the prophets.

–Matthew 7: 12 (King James Version)

There are many other instances of the Bible and religion being used as a weapon throughout American history, including the anti-Catholic “Bible Riots” in Philadelphia in 1844, which I wrote about in A Nation Rising.

Read more about the traditions of religious intolerance in my Smithsonian article “America’s True History of Religious Tolerance.”

May 28, 2020

“Two Societies, One Black, One White”

(Revised post originally published on February 29, 2016)

Once again, it is necessary to repost this piece about the Kerner Commission, formed fifty-three years ago to address violence in American cities.

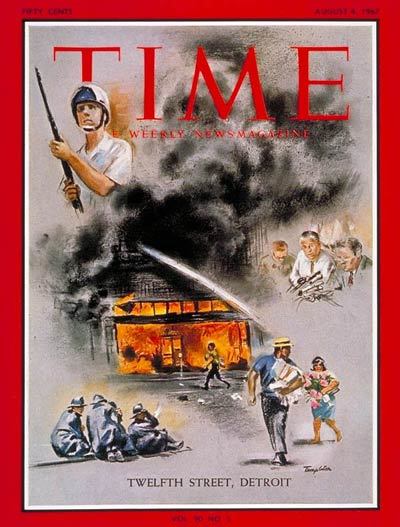

On July 27, 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson established an 11-member National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. He was responding to a series of violent outbursts in predominantly black urban neighborhoods in such cities as Detroit and Newark.

Time Magazine cover August 4, 1967

On July 29, 1967, President Johnson made remarks about the reasons for the commission:

The civil peace has been shattered in a number of cities. The American people are deeply disturbed. They are baffled and dismayed by the wholesale looting and violence that has occurred both in small towns and in great metropolitan centers.

No society can tolerate massive violence, any more than a body can tolerate massive disease. And we in America shall not tolerate it.

But just saying that does not solve the problem. We need to know the answers, I think, to three basic questions about these riots:

–What happened?

–Why did it happen?

–What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?

Source:Lyndon B. Johnson: “Remarks Upon Signing Order Establishing the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders.,” July 29, 1967. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

On Feb. 29, 1968, President Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, later known as the Kerner Commission after its chairman, Governor Otto Kerner, Jr. of Illinois, issued a stark warning:

“Our Nation Is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”

Governor of Illinois Otto Kerner, Jr., meeting with Roy Wilkins (left) and President Lyndon Johnson (right) in the White House. 29 July 1967 Source LBJ Presidential Library

The Committee Report went on to identify a set of “deeply held grievances” that it believed had led to the violence.

Although almost all cities had some sort of formal grievance mechanism for handling citizen complaints, this typically was regarded by Negroes as ineffective and was generally ignored.

Although specific grievances varied from city to city, at least 12 deeply held grievances can be identified and ranked into three levels of relative intensity:

First Level of Intensity

1. Police practices

2. Unemployment and underemployment

3. Inadequate housing

Second Level of Intensity

4. Inadequate education

5. Poor recreation facilities and programs

6. Ineffectiveness of the political structure and grievance mechanisms.

Third Level of Intensity

7. Disrespectful white attitudes

8. Discriminatory administration of justice

9. Inadequacy of federal programs

10. Inadequacy of municipal services

11. Discriminatory consumer and credit practices

12. Inadequate welfare programs

Source: “Our Nation is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”: Excerpts from the Kerner Report; American Social History Project / Center for Media and Learning (Graduate Center, CUNY)

and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University).

Issued half a century ago, the list of grievances reads as if it could have been written today.

May 25, 2020

Don’t Know Much About® Dorothea Lange

Daughter of Migrant Tennessee Coal Miner Living in American River Camp near Sacramento, California

(1936) by Dorothea Lange Credit: Gift of the Farm Security AdministrationMoMA Number:313.1938 Source: Museum of Modern Art

Dorothea Lange was born on May 26, 1895, in Hoboken,NJ. (2015 post; updated 5/26/2020)[image error]

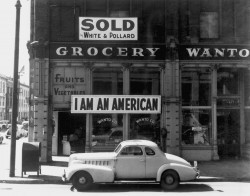

Best known for her photographs of Depression-era America, she also recorded the the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II.

Lange’s commitment to social justice and her faith in the power of photography remained constant throughout her life. In 1942, with the United States recently entered into World War II, the government’s War Relocation Authority assigned her to document the wartime internment of Japanese Americans, a policy she strongly opposed. She made critical images, which the government suppressed for the duration of the war.

–Dorothea Lange biographical entry from Museum of Modern Art

Photo by Dorothea Lange of Japanese-American grocery store on the day after Pearl Harbor Source: Library of Congress

Following the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor by Japan, there was a wave of fear and hysteria aimed at Japanese and people of Japanese descent living in America, including American citizens, mostly on the West Coast. In February 1942. President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which declared certain areas to be “exclusion zones” from which the military could remove anyone for security reasons. It provided the legal groundwork for the eventual relocation of approximately 120,000 people to a variety of detention centers around the country, the largest forced relocation in American history. Nearly two-thirds of them were American citizens. (Smaller numbers of Americans of German and Italian descent were also detained.)

Photo Source: National Archives

The attitude of many Americans at the time was expressed in a Los Angeles Times editorial of the period:

“A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched… So, a Japanese American born of Japanese parents, nurtured upon Japanese traditions, living in a transplanted Japanese atmosphere… notwithstanding his nominal brand of accidental citizenship almost inevitably and with the rarest exceptions grows up to be a Japanese, and not an American…” (Source: Impounded, p. 53)

The exclusion order was rescinded in 1945 and internees were allowed to leave, although many had lost their homes, businesses and property during their confinement. However, the last camp did not close until 1946.

In 1980, Congress established the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians to investigate the internment and, in 1988, President Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which provided for a reparation of $20,000 to surviving detainees.

One of those detainees was Albert Kurihara who told the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians in 1981:

“I hope this country will never forget what happened, and do what it can to make sure that future generations will never forget.” (from Impounded, Norton)

Photographer Dorothea Lange also photographed the internment camps and her censored images were published in 2006 in the book Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment (WW Norton, 2006).

The National Parks Service offers a Teaching With Historic Places lesson plan based on the camps some of which are now part of the National Parks System including Minidoka in Idaho and the Manzanar camp in California.

The Library of Congress offers an extensive collection of Lange photographs.

“Pea pickers in California. ‘Mam, I’ve picked peas from Calipatria to Ukiah. This life is simplicity boiled down.'” March, 1936. America from the Great Depression to World War II: Black-and-White Photographs from the FSA-OWI, 1935-1945, Library of Congress.

May 21, 2020

Who Said It (5/22/2020)

I always suggest reading this for Memorial Day

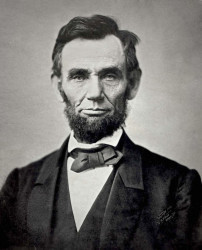

Abraham Lincoln, The Gettysburg Address (November 19, 1863)

“Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate, we cannot consecrate, we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead who struggled here have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living rather to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us–that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion–that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation under God shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people shall not perish from the earth.”

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

Complete Text Source: Avalon Project/Yale Law School

Learn more about the Gettysburg Address in Don’t Know Much About the Civil War and more about American slavery and the presidency in IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

May 19, 2020

The Divisive & Partisan History of “Memorial Day”

MEMORIAL DAY -MONDAY MAY 25, 2020

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (Photo: Arlington National Cemetery) This memorial was created after the great losses of World War I.

(Revise of 2015 post)

It is a well-established fact that Americans like to argue. And we do. Mays or Mantle. A Caddy or a Lincoln. And, of course, abolition, abortion, and guns. And now lockdowns.

There is no debate that Memorial Day 2020 will be unlike any other. Many traditional public celebrations and family gatherings will be severely curtailed.

But a debate over Memorial Day –and more specifically where and how it began? America’s most solemn holiday should be free of rancor. But it never has been.

The heated arguments over removing the Confederate flag and monuments to heroes and soldiers of the Confederacy in New Orleans and provide examples and reminders of the birth of Memorial Day.

In the Korean War, the U.S. military was integrated. (Source: Library of Congress)

Waterloo, New York claimed that the holiday originated there with a parade and decoration of the graves of fallen soldiers in 1866. But according to the Veterans Administration, at least 25 places stake a claim to the birth of Memorial Day. Among the pack are Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, which says it was first in 1864.( “Many Claim to Be Memorial Day Birthplace” )

And Charleston, South Carolina, according to historian David Blight, points to a parade of emancipated children in May 1865 who decorated the graves of fallen Union soldiers whose remains were moved from a racetrack to a proper cemetery.

Born out of the Civil War’s catastrophic death toll as “Decoration Day,” Memorial Day is a day for honoring our nation’s war dead. A veteran of the Mexican War and the Civil War, John A. Logan, a Congressman and leader of the Grand Army of the Republic, established the first somber commemoration on May 30, 1868, in Arlington Cemetery, the sacred space wrested from property once belonging to Robert E. Lee’s family.( When Memorial Day was No Picnic by James M. McPherson.) The Grand Army of the Republic was a powerful fraternal organization formed of Civil War Union veterans.

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

From its inception, Decoration Day (later Memorial Day) was linked to “Yankee” losses in the cause of emancipation. Calling for the first formal Decoration Day, Union General John Logan wrote, “Their soldier lives were the reveille of freedom to a race in chains…”

In other words, Logan’s first Decoration Day was divisive— a partisan affair, organized by northerners.

In 1871, Frederick Douglass gave a Memorial Day speech in Arlington that focused on this division:

We are sometimes asked, in the name of patriotism, to forget the merits of this fearful struggle, and to remember with equal admiration those who struck at the nation’s life and those who struck to save it, those who fought for slavery and those who fought for liberty and justice.

I am no minister of malice. I would not strike the fallen. I would not repel the repentant; but may my “right hand forget her cunning and my tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth,” if I forget the difference between the parties to that terrible, protracted, and bloody conflict.

But the question remains: what inspired Logan to call for this rite of decorating soldier’s graves with fresh flowers?

The simple answer is—his wife.

While visiting Petersburg, Virginia – which fell to General Grant in 1865 after a deadly, year-long siege – Mary Logan learned about the city’s women who had formed a Ladies’ Memorial Association. Their aim was to show admiration “…for those who died defending homes and loved ones.”

Choosing June 9th, the anniversary of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” in 1864, a teacher had taken her students to the city’s cemetery to decorate the graves of the fallen. General Logan’s wife wrote to him about the practice. Soon after, he ordered a day of remembrance.

The teacher and her students, it is worth noting, had placed flowers and flags on both Union and Confederate graves.

As America wages its partisan wars at full pitch, this may be a lesson for us all.

More resources at the New York Times Topics archive of Memorial Day articles

The story of “The Battle of the Old Men and the Young Boys” is told in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR (Now in paperback)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

May 13, 2020

Conversations- “Know More,” an online series with the National Council for History Education

Dear Educators,

In the next few weeks, while some of us are staying home during the Covid-10 pandemic, I’d like to share my love of history with you. Working with the National Council for History Education, I will do three virtual visits with students and teachers around the country.

These “Know More” sessions will take place on May 20, May 27 and June 3. Each will begin at 1:30 PM ET and last for 45 minutes to an hour.

You can learn more and register at the National Council for History Education website.

Here is what we will talk about:

•In our first get-together (May 20), we’ll talk about the worst pandemic in modern history— the Spanish flu — and what it had to do with the First World War. And we’ll also look at what lessons we can take from the Spanish flu pandemic today.

•In our second talk (May 27), we will discuss the history of slavery in the United States and the stories of five people who were enslaved by four U.S. presidents.

•This is an election year. So our third session (June 3) will be about how we elect a president. Come to mention it, why do we even have one?

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion paperback-April 15, 2014)

Each of these sessions will be a conversation— not a lecture. There won’t be any quick quizzes, tests, or papers to turn in. All you need to bring is your curiosity and your questions.

If you are a student from the middle or high school grades, I hope to see you there. Teachers and parents are welcome to join in as well as we talk about what we should learn from the past.

Space is limited. But we want you to be there. History matters. Now more than ever. When you have questions, ask!

“Return to Normalcy”

The Covid-19 pandemic is far from over but people are already asking what a post-pandemic world will look like. Will there be more telemedicine? Less time in the office? More remote learning?

The short answer is nobody really knows. But history can help. The sweeping changes that followed the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918-1919 offer some lessons.

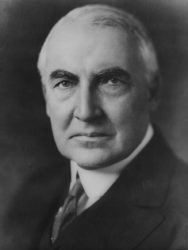

Following the pandemic of 1918-1919, which took 675,000 American lives, most people just wanted to feel “normal.” Ohio Senator Warren G. Harding made “Return to Normalcy” the centerpiece of his 1920 campaign and won the White House in a popular landslide.

Warren G. Harding (1920)

People also adopted a collective amnesia. The Spanish flu pandemic overlapped with the First World War and there was widespread sickness, death, and destruction. But while the First World War profoundly influenced art and literature, the Spanish flu pandemic left few marks in culture or popular memory.

There was no “pandemic literature.” Few novels, plays, movies, or paintings depicted the flu. A notable exception is Pale Horse, Pale Rider, a story written by Katherine Anne Porter, a survivor of the flu. No full-scale history of the flu was written until years later.

No surprise, the pandemic was followed by a desire to relax, have fun — even go a little wild– especially after after Prohibition was ushered in starting on January 17, 1920.

Detroit police inspecting equipment found in a clandestine underground brewery. (National Archives ID 541928)

Actress Louise Brooks an icon of “Flapper” style (Library of Congress http://loc.gov/pictures/resource/ggba...)

Famed entertainer Josephine Baker does the Charleston in Paris (1926 Wikimedia)

The 1920s brought loosening styles of clothing (Flappers!), music (Jazz!), dancing (the Charleston!), and the boom of Hollywood into one of the nation’s biggest businesses. It was the “Roaring Twenties.” After years of war and disease, people wanted to forget their troubles.

The status of women changed— they largely benefited. They had stepped in as nurses, factory workers, and teachers, helping the sick on the home front as others went to war. Women won the right to vote in federal elections in 1920 and voted in all 48 states that year.

And there was a dark side. During the pandemic, Germans were blamed for poisoning the water and causing the pandemic. Crowded tenements were hotspots and immigrants often got blamed for the outbreak. America retreated into isolationism and the anti-immigration laws passed after the pandemic were draconian. The fear of foreigners also emerged in the nation’s firest “Red Scare,” in which a young J. Edgar Hoover began his quest to find socialists, Bolsheviks and communists. And the hatred of immigrants, Jews, Catholics, and African Americans led to a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan, and with it a wave of lynchings.

Of course, the excitement of the “Roaring Twenties” would be short lived and come crashing down –literally– with Wall Street’s “Great Crash” in October 1929 and the Great Depression that followed.

I discuss some of these changes in my book More Deadly Than War and the era of the “Roaring Twenties” in Don’t Know Much About® History.