Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 37

July 17, 2020

Who Said It (July 17, 2020)

President Harry S. Truman, diary entry (July 17, 1945) describing meeting Soviet dictator Josef Stalin at the Potsdam Conference after Germany was defeated in World War II.

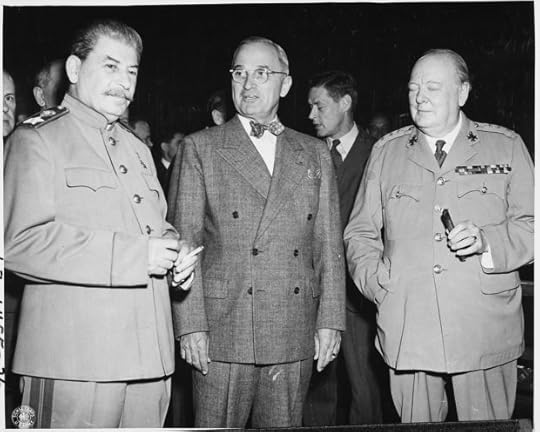

Truman had become president when Franklin D. Roosevelt died on April 1945. He met Stalin for the first time on July 17, 1945 at a meeting of the “Big Three” victorious allies in the war against Hitler’s Germany –The Soviet Union, Great Britain, and the United States.

With the war against Germany over, Truman wanted Stalin’s aid in defeating Japan.

Soviet Prime Minister Josef Stalin, President Harry S. Truman, and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill pose for the first time before the opening of the Potsdam Conference. PHOTO SOURCE: National Archies and Records Administration Harry S. Truman Library, cataloged under the National Archives Identifier (NAID) 198797.

“Promptly a few minutes before twelve I looked up from the desk and there stood Stalin in the doorway. I got to my feet and advanced to meet him. He put out his hand and smiled. I did the same. . . . After the usual polite remarks we got down to business. I told Stalin that I am no diplomat but usually said yes or no to questions after hearing all the argument (sic). It pleased him. I asked him if he had the agenda for the meeting. He said he had and that he had some more questions to present. I told him to fire away. He did and it is dynamite—but I have some dynamite too which I’m not exploding now. . . . I can deal with Stalin. He is honest—but smart as hell.”

—From President Truman’s Diary

Source: The National Archives “Eyewitness”

Truman’s “dynamite” was the revelation of the atomic bomb. He told the Soviet dictator about the atomic bomb which had been tested successfully in New Mexico the day before. The president was unaware that Stalin’s spies had already gotten much of the information about the “Manhattan Project” that developed the bombs later dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. Read about Hiroshima in this post.

This meeting and the events leading up to it are detailed in my book The Hidden History of America At War.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

July 16, 2020

Who Said It? (7/16/2020)

President Harry S. Truman on August 14, 1945 in remarks outside the White House after announcing the unconditional surrender of Japan.

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

“This is the day we have been waiting for since Pearl Harbor. This is the day when Fascism finally dies, as we always knew it would.”

Read more about the final days of World War II in this post on Hiroshima.

Here are Truman’s remarks after meeting Stalin in July 1945.

July 15, 2020

August 6-“Hiroshima Day” 75 Years Ago

The Atomic Bomb Dome-Hiroshima (Photo Courtesy of Hiroshima and Nagasaki Remembered)

[Repost of 2016 essay]

On August 6, 1945, the New York Times asked:

“What is this terrible new weapon?”

(Source, New York Times, August 6, 1945: “First Atomic Bomb Dropped on Japan”)

The story followed the announcement made by President Truman:

“SIXTEEN HOURS AGO an American airplane dropped one bomb on Hiroshima, an important Japanese Army base. That bomb had more power than 20,000 tons of T.N.T. It had more than two thousand times the blast power of the British ‘Grand Slam’ which is the largest bomb ever yet used in the history of warfare.”

August 6, 1945

President Harry S. Truman

(Photo: Truman Library)

(“Statement by the President Announcing the Use of the A-Bomb at Hiroshima”: Truman Library and Museum)

The first atomic bomb was exploded in a test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16, 1945.

Read this excellent account of the test in National Geographic.

President Truman, who had taken office upon the death of President Roosevelt on April 12 without knowledge of the Manhattan Project or the atomic bomb’s existence, was alerted to the success of this test at a meeting with Churchill and Stalin at Potsdam, a city in defeated Germany. (See this recent post on Potsdam)

The atomic bomb was detonated over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. A second device, a plutonium bomb, was used against the city of Nagasaki on August 9. Japan surrendered on August 14.

Almost since the day the first bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, critics have second-guessed Truman’s decision and motives. A generation of historians have defended or repudiated the need for unleashing the atomic weapon.

What history has confirmed is that the men who made the bomb really didn’t understand how horrifying its capabilities were. Of course, they understood the destructive power of the bomb, but radiation’s dangers were far less understood. As author Peter Wyden tells it in Day One, an account of the making and dropping of the bomb, scientists involved in creating what they called “the gadget” believed that anyone who might be killed by radiation would die from falling bricks first.

In less than one second, the fireball had expanded to 900 feet. The blast wave shattered windows for a distance of ten miles and was felt as far away as 37 miles. Over two-thirds of Hiroshima’s buildings were demolished. The hundreds of fires, ignited by the thermal pulse, combined to produce a firestorm that had incinerated everything within about 4.4 miles of ground zero.

The estimated death toll was eighty thousand people killed instantly in Hiroshima; as many as 90 percent of the city’s nurses and doctors also died instantly. By 1950, as many as 200,000 had died as a result of long-term effects of radiation.) The death toll in Nagasaki also reached 80,000 by the end of 1945.

Today should not be a day to argue about the politics of the bomb. It should be a day of solemn remembrance of these victims. And of contemplating the horrific power of the weapons we create.

The City of Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park and Museum offers an English language website with a history of Hiroshima and the effects of the bombing.

You can read more about Hiroshima and the dropping of the atomic bombs in Don’t Know Much About History and more about President Truman in Don’t Know Much About the American Presidents and in The Hidden History of America At War.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

July 13, 2020

Whose History Is It?

Whose history it is? And who gets to shape the narrative?

This is the hottest of hot potato questions, currently dominating the conversation about which dates we mark on the national calendar, whose statues we honor while others are pulled from their pedestals, and how we teach America’s past in our schools,

The comfortable, traditional American history so many Americans were once taught –sort of – has come down for centuries as a bedtime story. It is complete with a happy ending, a rousing tableau for a school pageant, or an instructive morality tale. Columbus’s first voyage and Washington’s cherry tree being Exhibits A and B.

Or it was the exclusive property of one powerful group that wanted to venerate its particular vision of pride. That was the reassuring tale of the first Thanksgiving Happy Meal, or Puritans arriving to establish a “shining city on a hill,” leaving out the indigenous and the dissidents –Roger Williams, Anne Hutchinson, Quakers, and Catholics—who were unwelcome on that hill.

The conflict between that traditional telling of history as American Exceptionalism and a so-called “revisionist” version is boiling over in the wake of the president’s discordantly curdled speech at Mount Rushmore on the eve of Independence Day.

Back in 1790, John Adams, who was present at the creation, offered a gloomy prediction of how the story would be told.

“The history of our Revolution will be one continued lie from one end to the other,” he wrote fellow Declaration signer Benjamin Rush. “The essence of the whole will be that Dr. Franklin’s electrical rod smote the earth and out sprang General Washington…. thenceforward these two conducted all the policies, negotiations, legislatures and the war.”

Adams was right. From the beginning, American history became a national myth. Controlling that narrative is a powerful tool. As Winston Churchill once remarked,

“History will bear me out, particularly as I shall write history myself.”

How we tell history and then drape it over national holidays or erect monuments to a selective account has always been subject to somebody’s agenda. Winners write history –usually. They tailored the story that became the national narrative, or the myth, depending on your perspective. But for the United States that proud, patriotic portrait came at the cost of the whole truth. And it left far too many people out of the picture.

The history widely celebrated on the Glorious Fourth rightly hailed a document that secured the timeless verities of “All men are created equal” and that all are entitled to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

In crafting that laudable lesson, however, some inconvenient truths were swept into history’s dustbin. When it comes to Independence Day, that meant concealing America’s Great Contradiction – that a nation “conceived in liberty” was also born in shackles.

In the current moment of reckoning, there is another agenda. We now acknowledge the purchase of captive Africans in Jamestown in 1619. The Mount Vernon plantation dedicated to honoring the first president now openly confronts the fact that Washington had enslaved more than 300 people at Mount Vernon at his death in 1799. Similarly, Jefferson’s Monticello no longer conceals that the author of the Declaration enslaved people, including his own offspring, born of an enslaved woman.

That history is messy. And the true beauty of American history is that it is not a tale that can be told in simple terms. It is complicated and nuanced. There are few neat answers which fit in a bubble on a standardized test form.

For instance, it is pointless to teach how Washington won the Battle of Yorktown in October 1781 without acknowledging that his first order of business after the surrender was to return thousands of enslaved people who had sought refuge with the British –including those from his Mount Vernon and Jefferson’s Monticello.

It’s absurd to teach a “melting pot” myth and a “religious freedom” narrative without talking about the deep vein of dominant anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic sentiments in America’s past that produced such moments as Philadelphia’s 1844 “Bible Riots,” a deadly sectarian battle begun over which version of the Bible was used in public schools.

Those are also American history “facts.” And as John Adams also famously said,

“Facts are stubborn things…whatever may be our wishes and inclinations or the dictums of our passions…”

Adams said that as he was defending the “bad guys” –the British soldiers who shot at some Boston townies in what became heralded as the Boston Massacre. It is a reminder that America’s rebellion began with an assault on authority. Some snowballs and stones were chucked at those British soldiers. That was followed by act of vandalism and property destruction, now hailed as the Boston Tea Party. And then some rebels tore down a statue—that of King George III, in New York City on July 9, 1776. This is all hailed in the “winner’s history” so many have been taught for so long.

And those are extremely important American history lessons. The rock-throwers, the tea party vandals, and the riotous statue-topplers of the American Revolution were part of the unruly mob that sometimes changes history.

History doesn’t trickle down from the top. Most of the great social movement in this nation’s history came instead from the bottom up. Independence, abolition, suffrage, civil rights, and marriage equality were largely fashioned by those who demonstrated a clear disregard for the law, with the nation’s “leaders” being dragged, kicking and screaming all the way to the finish line.

This is a hard, uncomfortable lesson for some. But in that fact lies the essence of American Exceptionalism.

Letter to Benjamin Rush, April 4, 1790.

“In the Churchill Museum,” Timothy Garton Ash, New York Review of Books, 7 May 1987 also cited in Leonard Roy Frank Quotationary, p. 359.

July 3, 2020

George Washington: A Monumental Reckoning

As the nation reckons with its horrific history of slavery, what do we do about George Washington?

You can also read my post “What Do We Do About George?”

July 2, 2020

What Do We Do About George?

Portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart (Source: Clark Institute Williamstown, Mass.)

It is July 4th, and as monuments to slavery are removed, defaced, and destroyed around the country, we need to ask a thorny question: What do we do about George?

Like many of the Founders, the Father of Our Country enslaved people. Inheriting ten people from his father at age eleven, Washington held more than three hundred men, women, and children in bondage at the time of his death in 1799. While one man was freed in Washington’s will, the others had to wait for Martha Washington to die. And roughly half of those people remained enslaved, parceled out among the Custis family, as part of the estate of Martha’s first husband.

In other words, George Washington was an enslaver from childhood to grave. And we have the receipts.

He once raffled off whole families in lots, including small children separated from parents. He later purchased four children at an estate sale, sending two dark-skinned boys to do fieldwork while two “mulatto” boys became house servants. Frank Lee became Mount Vernon’s butler and his brother Billy Lee served as Washington’s valet, his “loyal manservant,” for some thirty years.

The last remaining set of Washington’s dentures (Courtesy: Mount Vernon Ladies Association)

Washington’s own journal records that he purchased teeth pulled from the mouths of enslaved people, presumably to be fitted into his dentures. In exchange for a grocery list of rum, molasses, fruits, and sweetmeats, he once shipped off a man named Tom, a repeat runaway, and at least two other men to the cane fields of the West Indies.

And then there is the heroic Washington’s actions at Yorktown. After his signal victory over the British in 1781, General Washington wasted no time in recovering Esther, Lucy, Sambo Andersen, and fourteen others who had escaped Mount Vernon when offered the chance. They were among thousands of enslaved people who had fled to the British in hopes of emancipation. While Washington won America’s liberty, they lost theirs.

Did this inconsistency trouble Washington? The contradiction between his devotion to freedom while enslaving people did seem to prick his conscience. In 1786, he confided to fellow Founder Robert Morris, “there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it [slavery].”

But he did precious little to make it happen, either while presiding over the convention that cemented slavery in the Constitution, or as first president. After Philadelphia became the nation’s capital in 1790, President Washington shuttled enslaved servants in and out of the city to evade a Pennsylvania law that called for the emancipation of enslaved males residing in the state for more than six months. In 1793, he signed the Fugitive Slave Act, making assistance to runaways a federal offense.

When Ona Judge, Martha Washington’s enslaved maid, learned she would be given away as a wedding gift, she escaped from the home of the president in 1796. He advertised a ten-dollar reward for her return and spent the next three years trying to track down and recover a woman who had risked all for freedom.

For more than two centuries, these contradictions were given little weight by Washington’s admirers. The little boy who couldn’t tell a lie was immortalized as “First in the hearts of his countrymen.” The enslavement of human beings, especially by one of America’s most admired presidents, remained the dirty secret long concealed by textbooks and popular culture.

But a stunning moment of correction has arrived. It begs the questions:

Will George Washington’s picture be removed from the currency?

Will protestors project the images of African-American heroes onto Washington’s stern visage carved on Mt. Rushmore, as Harriet Tubman’s face now adorns Robert E. Lee’s statue in Richmond?

Washington Monument (Courtesy National Parks Service https://www.nps.gov/wamo/learn/histor...)

What about the Washington Monument?

We are now in a teachable moment. What we do is limited only by our creativity and the courage to be honest. We won’t take a chisel to the Washington Monument or spray paint it with graffiti. But draping the pristine obelisk with a “Black Lives Matter” banner in a moment of national reflection? That would let students and all Americans know that Washington was a flawed man who committed a crime against humanity while also building the nation. This was the “gross injustice and cruelty” that Frederick Douglass famously called out in his 1852 speech, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

Remaining silent on that injustice and cruelty is no longer an option. Because this is one of those “self-evident” truths. The United States was “conceived in liberty,” but born in shackles. We can no longer honor Washington’s indispensable achievements without recognizing his original sin.

What better occasion than Independence Day to be reminded of that.

July 1, 2020

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (11 of 11)

[Post revised 7/1/2020]

The Declaration Mural by Barry Faulkner (National Archives)

Key to Numbers in “The Declaration Mural” by Barry Faulkner

Last part of a series on the lives of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. (Previous post #10 here. From the blog page you can also scroll back through the series.

(A YES following the entry means the signer enslaved people; a NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

A New Hampshire slaver. A forgotten founder who died in debt and disgrace. A college president. A legendary bullet maker. Jefferson’s teacher –and a murder victim. Last but not least among the 56 signers.

–William Whipple (New Hampshire) Often described as a 46-year-old “merchant,” he was more precisely a sea captain who made a fortune sailing between Africa and the West Indies — in other words, the merchandise was human cargo.

He also enslaved people and one of those men, known as Prince, accompanied Whipple throughout his illustrious career as an officer in the Revolution. It was thought that Prince was the Black man depicted in the famous “Washington Crossing the Delaware” painting, but that is not accurate because Prince and Whipple were far from the action that night. Whipple later served in a variety of state offices in New Hampshire and legally manumitted Prince –who also went by the name of Caleb Quotum — in 1784. Whipple died in Portsmouth in 1785. YES

Gravestone of Prince Whipple https://www.blackpast.org/african-ame...

–William Williams (Connecticut) A 45-year-old merchant, he was a veteran of the French and Indian War who was under command of his uncle Ephraim Williams, who was shot and killed in the war. (Ephraim Williams’s will provided funds for the founding of what became Williams College in Massachusetts.) Planning to follow his father as a minister, he attended Harvard but instead opened a store and became a successful merchant.

Williams married Mary Trumbull, the daughter of Connecticut’s Royal Governor. Governor Trumbull was a Royal Governor who supported the patriot cause and was a friend and adviser of George Washington. One of Mary Trumbull’s brothers, John Trumbull, became the most famous painter of the American Revolution, and another later became Connecticut’s Governor.

William Williams was not present for the July vote but signed the Declaration and was a tireless supporter of the war effort. After a long career in public service, he died in 1811, aged 81. NO

–James Wilson (Pennsylvania) Scottish-born, he was a 33-year-old lawyer at the time of the signing and one of the most important Founding Fathers you probably never heard of. A key supporter of the Declaration, Wilson was among the signers and Philadelphia elites who were attacked in his home during the war in a riot over food prices and scarcity.

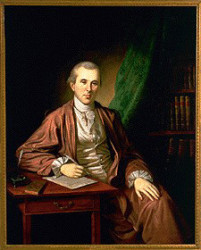

Wilson was also a key member of the Constitutional Convention, credited with several significant compromises. Although hopeful to be made Chief Justice of the new Supreme Court, he was appointed an associate by Washington. But land speculation ruined him and he ended up in debtor’s prison, like his colleague Robert Morris (See previous post #7) before his death in disgrace at age 55 in 1798, an embarrassment to his Federalist friends and colleagues. NO

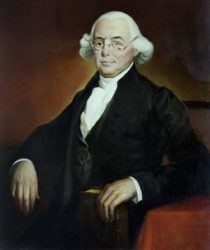

The official portrait of Supreme Court Justice James Wilson.

–John Witherspoon (New Jersey) Another profoundly influential immigrant, the Scottish-born minister was the 53-year-old president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) where his hatred of the British influenced many students including notable schoolmates Aaron Burr and James Madison. He lost a son at the battle of Germantown in 1777, but continued his career in Congress. After the war, he attempted to rebuild the college and was a prime mover in the growth and organization of the Presbyterian Church. He died in 1794 in Princeton, where he is buried, at age 71. YES

A photograph of Maclean House, also called the President’s House, at Princeton University. Built 1756. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

–Oliver Wolcott (Connecticut) A 49-year-old lawyer, he was also a veteran of the French and Indian War who was not present for the vote and signed at a later date. Wolcott was in New York when Washington’s troops tore down a statue of King George III after hearing the Declaration of Independence read. He is credited with the plan to melt down the lead statue and turn it into bullets for the war effort. He served in the Connecticut militia during the Revolution and held a series of state posts after the war including as governor of Connecticut at his death in 1797, aged 71. YES

–George Wythe (Virginia) A 50-year-old lawyer at the signing, he may have made his greatest mark as a teacher of law to Thomas Jefferson who lived with Wythe while at the College of William and Mary –as well as later students including James Monroe, future Chief Justice John Marshall, and congressman Henry Clay, earning him the title “America’s first law professor.”

He died in 1806 , around 80, apparently murdered by a nephew by arsenic poisoning. The nephew was perturbed that Wythe had emancipated his enslaved people and planned to give half his estate to one of those emancipated people. The nephew was acquitted of murder after the testimony of a formerly enslaved woman was disallowed because she was black. The nephew was convicted of forging his uncle’s checks. YES

George Wythe, Signer of Declaration of Independence New York Public Library Digital Gallery (Digital Image ID: 484381)

Read the story of James Wilson and the Philadelphia Riot in America’s Hidden History.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

June 30, 2020

Whatever Became of 56 Signers (Part 10 of 11)

(Post revised 6/30/2020: Part 10 of a series that begins here. Previous post #9 is here. A YES at the end of the entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

A victim of the British. Two Irish immigrants, one an indentured servant. A reluctant lawyer. An orphaned carpenter. Among the next five of 56 signers.

–Richard Stockton (New Jersey) Of the signers who paid for their actions, this successful and much-admired 45-year-old attorney at the signing, may have suffered most. Betrayed by Tory Loyalists in his home state, he was captured by the British in 1776, although later released in a prisoner exchange, not for having sworn allegiance to the King, as reported in a much-disputed rumor of the day. His New Jersey home was also damaged by the British but later restored. Stockton was in poor health after the experience in captivity but lived until 1781, when he died of throat cancer.

Stockton is also credited with recruiting John Witherspoon, an influential Sottish minister, (See next installment in series) to become president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton). His daughter, Julia, was married to Benjamin Rush, another signer.

“Stockton’s home ‘Morven’ had been occupied by British General Cornwallis. Dr. Benjamin Rush wrote: ‘The whole of Mr. Stockton’s furniture, apparel, and even valuable writings have been burnt. All his cattle, horses, hogs, sheep, grain and forage have been carried away by them. His losses cannot amount to less than five thousand pounds.’” (Source: The Society of the Descendants of the Signers.)

His home Morven, later served as the New Jersey Governor’s Mansion from 1954-1981. Today, his name is familiar to most people because there is rest stop on the New Jersey Turnpike named in his honor. YES

–Thomas Stone (Maryland) Among the conservatives in Congress, he was a 33-year-old attorney at the signing, reluctant about independence, but then joining in the favorable vote.He wrote:

“I wish to conduct affairs so that a just and honorable reconciliation should take place, or that we should be pretty unanimous in a resolution to fight it out for independence. The proper way to effect this is not to move too quick. But then we must take care to do everything which is necessary for our security and defense, not suffer ourselves to be lulled or wheedled by any deceptions, declarations or givings out. You know my heart wishes for peace upon terms of security and justice to America. But war, anything, is preferable to a surrender of our rights.” (Source: The Society of the Descendants of the Signers)

Another son of a wealthy planter, he had a low profile after the signing, helping write the Articles of Confederation but not signing them. He also declined to take part in the Constitutional Convention, when his wife, who fell ill following an earlier inoculation against smallpox, died in 1787. Apparently despondent, he died four months later in 1787 at age 44. YES

–George Taylor (Pennsylvania) Arriving in America as an indentured servant from Ireland, he was a 60-year-old merchant and iron maker at the signing. He had risen at the foundry where he worked to become bookkeeper, then bought the business after his employer’s death and then married the late owner’s widow. Taylor was not in the influential Pennsylvania delegation for the July vote, but signed the document in August. During the war, his foundry provided cannon and cannonballs for the war effort, but Congress was notoriously slow to pay its bills and his business suffered. He died in 1781 at age 65. YES

–Matthew Thornton (New Hampshire) An Irish-born physician, he was around 62 at the signing, a veteran surgeon who had served with the New Hampshire militia in the French and Indian War. A latecomer to Congress, he joined in November 1776 and was later permitted to add his name to the document. He later served as a state judge and then operated a farm and ferry before his death in 1803 at about age 89. NO

–George Walton (Georgia) Orphaned and apprenticed as a carpenter, he was a 35-year-old, self taught attorney at the signing. Although his exact birth date is unknown, some claim that he was the youngest Signer – a distinction usually given to Edward Rutledge (See previous entry). Serving with the Georgia militia, he was shot and captured by the British in 1778. He was held for a year before being exchanged for a British officer –even though it was known he was a signer. He later served in a variety of state offices, including governor and senator from Georgia, and built a home on lands confiscated after the war from a Tory, or Loyalist. He is implicated in the events that led to the duel that killed fellow signer and political rival Button Gwinnet (see Part 3 of series). He died in 1804, aged 63 (?) . Possible No. As a Quaker, Walton may have favored abolition. [Unable to confirm his status regarding slavery pending further investigation.]

. Possible No. As a Quaker, Walton may have favored abolition. [Unable to confirm his status regarding slavery pending further investigation.]

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

June 29, 2020

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (Part 9)

(Post updated 6/29/2020: Part 9 in a series that begins here Previous post #8 here a YES following the entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

Betsy Ross’s uncle. The “first psychiatrist.” Youngest signer. The Great Compromiser. An Irishman named Smith. The next five signers:

–George Ross (Pennsylvania) The son of a Scottish-born minister, he was a 46-year-old attorney at the signing, a Loyalist or Tory, before turning to the Patriot cause in 1775. He served as a Colonel in the Pennsylvania militia. Yes, he was Betsy’s uncle by marriage, but the rest of the Ross flag story has been dismissed as family legend. Ross left Congress in early 1777 due to illness — severe gout, a form of arthritis once described as the “rich man’s disease” that afflicted a number of other signers. He later served as a Pennsylvania judge before his death in 1779 at 49, following a severe attack of gout. NO

Dr Benjamin Rush by Charles Willson Peale c. 1783. Winterthur Museum

–Benjamin Rush (Pennsylvania) Raised by a widowed mother, he was a 30-year-old physician at the signing, youngest in the influential Pennsylvania delegation. He was elected after the July vote and his diaries, letters, and notes provided some of the best portraits of many of the signers and other founders.

He served as surgeon general of the armies during the war, and became an early abolitionist while still a slaveholder himself. Rush was also an early advocate of many modern medical practices, while at the same time practicing bloodletting. He established the first free medical clinic and remained in Philadelphia during a yellow fever epidemic in 1793 when the city was the nation’s capital, spoke against capital punishment, and in favor of the idea that there was mental illness which led to his being called “The Father of American Psychiatry.” He died of typhus in 1813 at age 67. YES

–Edward Rutledge (South Carolina) Son of an Irish immigrant physician, he was a 26-year-old attorney at the signing, the youngest of the signers. A wealthy planter as well as a much-admired attorney, Rutledge initially opposed the Declaration before changing his mind to support the favorable vote. He later left Congress and was captured by the British while serving in the militia when Charleston fell in May 1780. He was held in St. Augustine for nearly a year. After the war, his finances and businesses flourished and he returned to state politics. Offered a Supreme Court seat bvy George Washington, he was instead elected governor of South Carolina in 1789, but died at age 50 in 1800, before his term ended. YES

–Roger Sherman (Connecticut) A self-educated son of a farmer, he was a prosperous merchant, attorney, and politician, aged 55 at the signing. He would sign three of the central documents in America’s foundation: the Declaration (he was a member of the draft committee), the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution. It was at the 1787 convention that Sherman proposed the “Great Compromise” that ended the deadlock between large and small states. He was also a true “Founding Father”– after Carroll (18 children) and Ellery (16 children), Sherman fathered the third most children among the signers -15. A leading Federalist, he served in the House and Senate, where he was serving at his death in 1793 at age 72. NO

–James Smith (Pennsylvania) Another immigrant signer, he was born in Northern Ireland and was around 57-years-old at the signing, another self-taught attorney. He had been an outspoken advocate of challenging oppressive British laws and called for the boycott of British goods that was later adopted by the First Continental Congress. Her also joined the Pennsylvania militia and was elected an officer. After the July vote, he signed the Declaration and then rode to York, Pennsylvania to have it read aloud on July 6. He served as Brigadier General of the Pennsylvania militia and later returned to law practice and state offices before his death in 1806 at about age 87. NO

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

June 28, 2020

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (Part 8)

[Updated 6/28/2020: Part 8 of a blog series that begins here. Part 7 here. Note: YES following an entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.]

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

Minister turned whaleboat captain and lawyer. Self-taught planters’ sons. A Nay vote. A rare bachelor. And a veiled man. The next six signers:

–Thomas Nelson, Jr. (Virginia) Another son of a wealthy planter. he was a 37-year-old merchant-planter at the signing, owner of more than 400 enslaved people. He raised money to supply troops and even commanded militia. Legend has it that he fired a cannon at his own Yorktown mansion during the 1781 siege when told that it was British headquarters. The war cost him financially and he was in ill health, retiring as Virginia’s governor and living on his plantation until his death at 50 in 1789. YES

–William Paca (Maryland) An attorney and wealthy planter’s son, he was 35 at the signing. A patriot leader in somewhat conservative Maryland, Pace (pronounced Pay-cah) helped bring the state to favor independence at Philadelphia. He raised funds for the war effort and later, as Congressman, worked to support veterans.

A firm believer in states rights and individual rights, Paca was a leader of the Antifederalist movement in Maryland.

William Paca by Charles Willson Peale MSA SC 4680-10-0083 Source Maryland State House

“Even though he had many reservations, he voted in 1788 to approve the Constitution. He advocated 28 amendments to the Constitution, including those on freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and protection against judicial tyranny, and many of his proposed amendments became a part of the Bill of Rights.” [Source: The Society of the Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration.]

He was twice married, but both wives died after childbirth, and Paca also fathered two children out of wedlock, one to a mixed race woman while serving in Philadelphia, according to the Society of the Descendants. He was later appointed a federal judge by President Washington, and was in that post at his death in 1799 at age 58. YES

Robert Treat Paine (Courtesy: Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts)

–Robert Treat Paine (Massachusetts) Overshadowed by two Adamses and Hancock, he was a minister turned attorney, 45-years-old at the signing, who had also been a sea captain on a whaler.

“In 1754, as Captain of the Seaflower, he led a whaling expedition from Cape Cod to Greenland and left behind what is believed to be the earliest illustrated log of a whaling venture kept by an American.” [Source: Society of the Descendants of the Signers]

He is perhaps best known as one of the prosecutors in the 1770 trial of the British soldiers charged in “Boston Massacre.” His friend and fellow delegate John Adams had served successfully as their defender. In 1780, he was among the founders of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the first American groups dedicated to expanding scientific knowledge and learning. After the war, he remained active in Massachusetts politics, becoming the state’s Attorney General, and was named a state judge by John Hancock until his retirement in 1804 due to deafness. He died in 1814 at age 83. NO

–John Penn (North Carolina) A wealthy planter’s son who taught himself to read and write, he was a 36-year-old attorney at the signing. He remained in Congress and was one of the signers who also signed the first American constitution, the Articles of Confederation. He retired to private law practice and died in 1788 at age 48. YES

–George Read ( Delaware) Among the conservative delegates, he was a 42-year-old lawyer at the time of the signing but had voted against independence on July 2.He served in state offices until ill health forced his resignation. But he returned to Philadelphia to take part in the Constitutional convention and was leading voice for small states’ rights and led the ratification forces in Delaware, the first state to ratify the Constitution. Elected to the Senate, he resigned to take a judgeship in Delaware before his death in 1798 at age 65. YES

Statue of Caesar Rodney on his ride-Rodney Square Wilmington, DE (Public Domain)

–Caesar Rodney (Delaware) Another self educated attorney, son of a planter, he was 47 at the signing. Rodney exemplifies the Great Contradiction of the Declaration, as he had earlier introduced legislation against the foreign slave trade:

“In 1766, as the Speaker of the [Delaware] Assembly, he introduced a bill to prohibit the importation of slaves into Delaware. At this time he was living in Byfield, a plantation of 1,000 acres, and owned 200 slaves. It is clear that he was pondering questions of the Colony’s and Mankind’s liberty and freedom. Indeed, at his death fourteen years later, he directed that all his slaves should be freed then, or shortly thereafter.” [Source: The Society of the Descendants]

He is perhaps best known for an 80-mile ride in a storm to break a deadlock that put Delaware in the Independence column –which cost him favor with conservatives in his home state. He later wrote in a letter:

“I arrived in Congress (tho detained by thunder and rain) time enough to give my voice in the matter of independence . . . We have now got through the whole of the declaration and ordered it to be printed so that you will soon have the pleasure of seeing it.” [Source: The Society of the Descendants]

One of the three bachelor signers (Francis Lee and Thomas Lynch were the others), he remained in the Congress until he became Delaware’s state president. A cancerous growth on his face was untreated and he covered it with a silk veil, worn for a decade before his death in 1784 at age 55. YES