Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 44

September 13, 2019

“Democracy is Not a Spectator Sport”

“Sometimes democracy dies quickly. Sometimes it dies the death of a thousand small cuts, lingering before taking a last breath. But rarely does it meet its demise in darkness. Very often, democracy dies in broad daylight.”

-Kenneth C. Davis “Democracy is Not a Spectator Sport” (Social Education, September 2019)

Democracy is under assault. Both around the globe and in the United States. The threat is very real. Civic engagement –the action of the people to determine what happens– is the best defense of democracy. But it currently stands at a frightening low in the United States.

Mussolini and Hitler in Munich June 1940 (Source National Archives)

My article, Democracy is Not a Spectator Sport: The Role of Social Studies in Safeguarding the Republic, appears in the September issue of Social Education, the magazine of the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS). It discusses the real threats to democracy, what underlies these threats, and most important, what teachers and citizens can do about it. The complete article appears below.

History shows us that democracy is very fragile and can vanish quickly –if we let it. This is the story I will tell in my forthcoming book, STRONGMAN: The Rise of Five Dictators and the Fall of Democracy, which will be published in October 2020 (Holt).

se_8304180

September 12, 2019

Don’t Know Much About® the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire

Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire on March 25, 1911 from front page of The New York World (Source: [Post revised from original on 3/25/2011]Cornell University ILR School Kheel Center © 2011)

[Reposted from original on 3/25/2011]On this date, March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory in New York caught fire and 146 people died, most of them women between the ages of 16 and 23.

“Look for the union label.”

If you are of a certain generation, you may recognize those words instantly. They are the first line of a song that became a 1970s advertising icon.

Sung by a swelling chorus of lovely ladies (and a few men) of all colors, shapes and sizes, it was the anthem of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union.

Airing as American unions began to confront the long, steady drain of jobs to cheaper foreign labor markets, the song rousingly implored us to look for the union label when shopping for clothes (“When you are buying a coat, dress or blouse”).

Seeing these earnest women, thinking of them at their sewing machines, made us race to the closet and check our clothes for that ILGWU tag. (“It says we’re able to make it in the USA.”)

The International Ladies Garment Worker Union was born in 1900, in the midst of the often-violent period of early 20th century labor organizing when brutal working conditions and child labor were the norm in America’s mines and factories.

One of the companies the union attempted to organize was the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory at what is now Greene Street and Washington Place in New York’s Greenwich Village. It employed many poor and mostly immigrant women, most of them Jewish and Italian.

A walkout against the firm in 1909 helped strengthen the union’s rolls and led to a union victory in 1910. But the Triangle Shirtwaist Company –which would chain its doors shut to control its workers— earned infamy when a fire broke out on March 25, 1911 and 146 workers were trapped in the flaming building and died. Some jumped to their deaths.

A police officer and others with the broken bodies of Triangle fire victims at their feet, look up in shock at workers poised to jump from the upper floors of the burning Asch Building. (Credit: Cornell University ILR School Kheel Center ©2011)

The two owners of the factory were indicted but found not guilty. The tragedy helped galvanize the trade union movement and especially the ILGWU.

On the 105th anniversary of that dreadful event, it is worth remembering that American prosperity was built on the sweat, tears and blood of working men and women. Immigration and jobs are the issue again today, just as they were more than a century ago.

Cornell University’s Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation offers a web exhibit on the Triangle Factory Fire. The Library of Congress also offers resources on the tragedy.

On February 28, 2011, American Experience on PBS aired a documentary film about the tragedy and the period.

The site is part of New York University and a National Historic Landmark.

August 26, 2019

Labor Day 2019

“Labor is the superior of capital and deserves much the higher consideration.”

— Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (December 3, 1861)

To most Americans, the first Monday in September means a three-day weekend and the last hurrah of summer, a final outing at the shore before school begins, a family picnic. The federal Labor Day was signed into law by President Grover Cleveland during his second term in 1894.

But Labor Day was born in a time when work was no picnic. As America was moving from farms to factories in the Industrial Age, there was a long, violent, often-deadly struggle for fundamental workers’ rights, a struggle that in many ways was America’s “other civil war.” (From “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”)

“Glassworks. Midnight. Location: Indiana.” From a series of photographs of child labor at glass and bottle factories in the United States by Lewis W. Hine, for the National Child Labor Committee, New York.

The first American Labor Day is dated to a parade organized by unions in New York City on September 5, 1882, as a celebration of “the strength and spirit of the American worker.” They wanted among, other things, an end to child labor.

In 1861, Lincoln told Congress:

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights. Nor is it denied that there is, and probably always will be, a relation between labor and capital producing mutual benefits. The error is in assuming that the whole labor of community exists within that relation.

Today, in postindustrial America, Abraham Lincoln’s words ring empty. Labor is far from “superior to capital.” Working people and unions have borne the brunt of the great changes in the globalized economy.

But the facts are clear: In the current “gig economy,” the loss of union jobs and the recent failures of labor to organize workers is one key reason for the decline of America’s middle class.

This excellent essay by former Labor Secretary Robert Reich explores the vast inequities existing in America’s economy.

Read the full history of Labor Day in this essay: “The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day” (2011)

Who Said It? (8/26/2019-Labor Day edition)

(Reposted from 2014)

Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration.

Abraham Lincoln (November 1863) Photo by Alexander Gardner

Abraham Lincoln, “First Annual Message to Congress” (“State of the Union”) December 3, 1861

It is not needed nor fitting here that a general argument should be made in favor of popular institutions, but there is one point, with its connections, not so hackneyed as most others, to which I ask a brief attention. It is the effort to place capital on an equal footing with, if not above, labor in the structure of government. It is assumed that labor is available only in connection with capital; that nobody labors unless somebody else, owning capital, somehow by the use of it induces him to labor. This assumed, it is next considered whether it is best that capital shall hire laborers, and thus induce them to work by their own consent, or buy them and drive them to it without their consent. Having proceeded so far, it is naturally concluded that all laborers are either hired laborers or what we call slaves. And further, it is assumed that whoever is once a hired laborer is fixed in that condition for life.

Now there is no such relation between capital and labor as assumed, nor is there any such thing as a free man being fixed for life in the condition of a hired laborer. Both these assumptions are false, and all inferences from them are groundless.

Labor is prior to and independent of capital. Capital is only the fruit of labor, and could never have existed if labor had not first existed. Labor is the superior of capital, and deserves much the higher consideration. Capital has its rights, which are as worthy of protection as any other rights.

Source and Complete text: Abraham Lincoln: “First Annual Message,” Read more about Lincoln, his life and administration and the Civil War in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the Civil War and Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents

Don’t Know Much About the Civil War (Harper paperback, Random House Audio)

[image error]

Don’t Know Much About® History: Anniversary Edition (Harper Perennial and Random House Audio)

[image error]

Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents (Hyperion Paperback-April 15, 2014)

July 24, 2019

Don’t Know Much About Impeachment?

(Revise of original post dated 6/19/2017)

“An impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history.”

–House Minority Leader Gerald Ford (April 1970)

In the summer of 1787, as the framers debated the Constitution, Benjamin Franklin worried about how to get ride of corrupt or incompetent officials. Without some method of removal, the only recourse was assassination.

The other delegates agreed. And after considerable debate, they added the power of impeachment to the list of checks and balances of the legislature on the other two branches.

To date, the Senate has conducted formal impeachment proceedings 19 times, resulting in seven acquittals, eight convictions, three dismissals, and one resignation with no further action.

Gerald Ford knew how high that bar was set. In 1970, he failed in his attempt to impeach Douglas. The FDR-appointed liberal justice had already survived an earlier impeachment attempt over his brief stay of execution for convicted spy Ethel Rosenberg. This time, the supposed offense was financial impropriety, but Ford and others also clearly balked at Douglas’s liberal views. The majority of the House disagreed, and Douglas stayed on the bench.

So far, only two American presidents have been impeached and tried in the Senate: Andrew Johnson—Lincoln’s successor—and Bill Clinton. Both were acquitted. Richard Nixon would certainly have been impeached had he not resigned his office in August 1974.

Of the other impeachment cases since 1789, one was of a senator—William Blount of Tennessee, case dismissed in 1799—and one a cabinet officer, Secretary of War William Belknap, who was acquitted in 1876. Most of the other impeachment cases have involved federal judges, eight of whom have been convicted.

Read a brief history of impeachment in this article from Smithsonian, “The History of American Impeachment.”

Read more about the Constitutional power of impeachment in these articles from the National Constitution Center.

July 1, 2019

Jefferson’s Version-A few key differences

This is a post I wrote in 2009 after visiting the hand written copy Thomas Jefferson made of his draft version of the Declaration at the New York Public Library:

Last evening, I had a thrilling experience. In a small, darkened room with the feel of a chapel inside the magnificent New York Public Library, I saw Thomas Jefferson’s handwritten copy of his original draft of the Declaration of Independence. For me this was a “Grail Moment.” Setting aside all of Jefferson’s contradictions and human flaws, I found the experience of seeing these words in his own hand exhilarating.

We take them for granted, of course. But Jefferson gave full voice to the idea that we all possess “inalienable rights” –That we are “created equal.” That we have basic rights to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” That governments exist to advance those human rights, and only with the “consent of the governed.”

The document is written on both sides of two pieces of paper. In his careful, flowing script, Jefferson included all of his original wording to show what the Congress in Philadelphia had changed, underscoring words and phrases that had been deleted. Those alterations, Jefferson, thought were “mutilations.” Distressed by the editing, he made these “fair copies” of his original some time after July 4th. (The document on display at the New York Public Library is one of only two known surviving copies.)

Jefferson’s Desk on which he drafted the Declaration (Image: American Museum of History/Smithsonian)

The most startling of these changes is a paragraph about what Jefferson calls “this execrable commerce” — slavery. Jefferson charged –rather ridiculously, of course– that King George III was responsible for the slave trade and was preventing American efforts to restrain that trade. The section was deleted completely. But it is striking to see Jefferson’s bold, block lettering when he describes:

an open market where MEN should be bought & sold

Yes, he was going home to a plantation completely dependent upon slave labor. But he clearly wanted to underscore his belief that slaves were MEN. The contradiction is stunning, troubling, and difficult to resolve.

As the nation approaches its celebration of Independence and the ideals of “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness,” it is always crucial –and challenging– to remember that with those rights comes responsibility. We have traveled a remarkable road in 233 years (in 2018: 242 years). There is no more powerful symbol of that distance than the fact that an African American has been elected president.

But we still have far to go until we all have secured all of those rights –equality, life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness– for all of the people. Jefferson and his 55 fellow signers pledged their lives, fortunes and “sacred honor” in support of those fundamental human rights. Would we all be willing to say the same?

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (11 of 11)

The Declaration Mural by Barry Faulkner (National Archives)

Key to Numbers in “The Declaration Mural” by Barry Faulkner

Last part of a series on the lives of the 56 men who signed the Declaration of Independence, adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 4, 1776. (A YES following the entry means the signer enslaved people; a NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

A New England slaver. A forgotten founder who died in debt and disgrace. A college president. A legendary bullet maker. Jefferson’s teacher –and a murder victim. Last but not least among the 56 signers.

–William Whipple (New Hampshire) Usually described as a 46 year old merchant, he was more precisely a sea captain who made a fortune sailing between Africa and the West Indies — in other words, the slave trade. He also enslaved people and one of those men, known as Prince, accompanied Whipple throughout his illustrious career as an officer in the Revolution. It was thought that Prince was the black man depicted in the famous “Washington Crossing the Delaware” painting, but that is not accurate because Prince and Whipple were far from the action that night. Whipple later served in a variety of state offices in New Hampshire and legally manumitted Prince –who also went by the name of Caleb Quotum — in 1784. Whipple died in Portsmouth in 1785. YES

Gravestone of Prince Whipple https://www.blackpast.org/african-ame...

–William Williams (Connecticut) A 45 year old merchant, he was a veteran of the French and Indian War who had married the daughter of Connecticut’s Royal Governor. He was not present for the July vote but signed the Declaration and was a tireless supporter of the war effort. After a long career in public service, he died in 1811, aged 71. NO

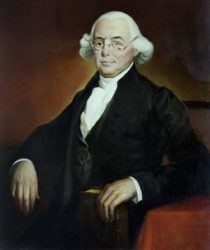

–James Wilson (Pennsylvania) Scottish born, he was a 33 year old lawyer at the time of the signing and one of the most important Founding Fathers you probably never heard of. A key supporter of the Declaration, Wilson was among the signers and Philadelphia elites who were attacked in his home during the war in a riot over food prices and scarcity. Wilson was also a key member of the Constitutional Convention, credited with several significant compromises. Although hopeful to be made Chief Justice of the new Supreme Court, he was appointed an associate by Washington. But land speculation ruined him and he ended up in debtor’s prison, like his colleague Robert Morris (See previous post #7) before his death in disgrace at age 55 in 1798, an embarrassment to his Federalists friends and colleagues. NO

The official portrait of Supreme Court Justice James Wilson.

–John Witherspoon (New Jersey) Another profoundly influential immigrant, the Scottish born minister was 53 year old president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) where his hatred of the British influenced many students including notable schoolmates Aaron Burr and James Madison. He lost a son at the battle of Germantown in 1777 but continued his career in Congress. After the war, he attempted to rebuild the college and was a prime mover in the growth and organization of the Presbyterian Church. He died in 1794 in Princeton, where the is buried, at age 71. YES

A photograph of Maclean House, also called the President’s House, at Princeton University. Built 1756. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Fi...

–Oliver Wolcott (Connecticut) A 49 year old lawyer, he was a veteran of the French and Indian War who was not present for the vote and signed at a later date. Wolcott was in New York when Washington’s troops tore down a statue of King George III after hearing the Declaration of Independence read. He is credited with the plan to melt down the lead statue and turn it into bullets for the war effort. He served in the Connecticut militia during the Revolution and held a series of state posts after the war including as governor of Connecticut at his death in 1797 , aged 71. YES

–George Wythe (Virginia) A 50 year old lawyer, he made his greatest mark as a teacher of law to Thomas Jefferson at the College of William and Mary –as well as later students including James Monroe, future Chief Justice John Marshall and congressman Henry Clay, earning him the title “America’s first law professor.” He died in 1806 , around 80, apparently murdered by a nephew who was perturbed that Wythe was planning to free the slaves that the young man was supposed to inherit. (The nephew was acquitted of murder but convicted of forging his uncle’s checks). YES

George Wythe, Signer of Declaration of Independence New York Public Library Digital Gallery (Digital Image ID: 484381)

Read the story of James Wilson and the Philadelphia Riot in America’s Hidden History.

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

June 30, 2019

Whatever Became of 56 Signers (Part 10 of 11)

(Part 10 of a series that begins here. A YES at the end of the entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

A victim of the British. Two Irish immigrants. An orphaned carpenter. Among the next five of 56 signers.

–Richard Stockton (New Jersey) Of the signers who clearly suffered for his actions, this successful and widely-admired 45 year old attorney at the signing, may have suffered most. Stockton is also credited with recruiting John Witherspoon, an influential Sottish minister, (See next installment in series) to become president of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton). Betrayed by loyalists in his home state, he was captured by the British in 1776, although later released in a prisoner exchange, not for having sworn allegiance to the King, as reported in a much-disputed rumor of the day. His New Jersey home was also damaged by the British but later restored. Stockton was in poor health after the experience in captivity but lived until 1781, when he died of throat cancer. His daughter, Julia, was married to Benjamin Rush, another signer. Today, his name is familiar to most people because there is rest stop on the New Jersey Turnpike named in his honor. YES

–Thomas Stone (Maryland) Among the conservatives in Congress, he was a 33 year old attorney at the signing, reluctant about independence, but then joining in the favorable vote. Another son of a wealthy planter, he had a low profile after the signing, helping write the Articles of Confederation but not signing them. He also declined to take part in the Constitutional Convention, when his wife, who fell ill following an inoculation against smallpox, died in 1787. Apparently despondent, he died four months later in 1787 at age 44. YES

–George Taylor (Pennsylvania) Arriving in America as an indentured servant from Ireland, he was a 60 year old merchant and iron maker at the signing. He had risen at the foundry where he worked to become bookkeeper, then bought the business after his employer’s death and then married the late owner’s widow. Taylor was not in the influential Pennsylvania delegation for the July vote, but signed the document in August. During the war, his foundry provided cannon and cannonballs for the war effort, but Congress was notoriously slow to pay its bills and his business suffered. He died in 1781 at age 65. YES

–Matthew Thornton (New Hampshire) An Irish-born physician, he was around 62 at the signing, a veteran surgeon who had served with the New Hampshire militia in the French and Indian War. A latecomer to Congress, he joined in November 1776 and was later permitted to add his name to the document. He later served as a state judge and then operated a farm and ferry before his death in 1803 at about age 89. NO

–George Walton (Georgia) Orphaned and apprenticed as a carpenter, he was a 35 year old self taught attorney at the signing. Although his exact birth date is unknown, some claim that he was the youngest Signer – a distinction usually given to Edward Rutledge (See previous entry). Serving with the Georgia militia, he was shot and captured by the British in 1778. Well-treated, he was held for a year before being exchanged for a British officer –even though it was known he was a signer. He later served in a variety of state offices, including governor and senator from Georgia, and built a home on lands confiscated after the war from a Tory, or Loyalist. He is implicated in the events that led to the duel that killed fellow signer and political rival Button Gwinnet (see Part 3 of series). He died in 1804, aged 63 (?) . Possibly No. As a Quaker, Walton may have favored abolition. [?Unable to confirm his status pending further investigation.]

. Possibly No. As a Quaker, Walton may have favored abolition. [?Unable to confirm his status pending further investigation.]

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

June 29, 2019

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (Part 9)

(Part 9 in a series that begins here; a YES following the entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.)

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

Betsy Ross’s uncle. The “first psychiatrist.” Youngest signer. The Great Compromiser. An Irish man named Smith. The next five signers:

–George Ross (Pennsylvania) The son of a Scottish-born minister, he was a 46 year old attorney at the signing, a loyalist before turning to the patriot cause in 1775. Yes, he was Betsy’s uncle, but the rest of the Ross flag story has been dismissed as family legend. He left Congress in early 1777 due to illness — the same severe gout that afflicted a number of signers– and served as a Pennsylvania judge before his death in 1779 at 49, following a severe attack of gout. NO

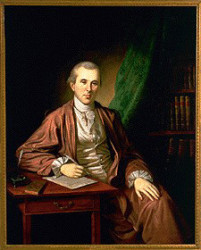

Dr Benjamin Rush by Charles Willson Peale c. 1783. Winterthur Museum

–Benjamin Rush (Pennsylvania) Raised by a widowed mother, he was a 30 year old physician at the signing, youngest in the Pennsylvania delegation. He was elected after the July vote and his diaries, letters, and notes provided some of the best portraits of many of the signers and other founders. He served as surgeon general of the armies during the war, and became an early abolitionist while still a slaveholder himself. Rush was also an early advocate of many modern medical practices, while at the same time practicing bloodletting. He established the first free medical clinic and remained in Philadelphia during a yellow fever epidemic, spoke against capital punishment, and in favor of the idea that there was mental illness which led to his being called “The Father of American Psychiatry.” He died of typhus in 1813 at age 67. YES

–Edward Rutledge (South Carolina) Son of an Irish immigrant physician, he was a 26 year old attorney at the signing, the youngest of the signers. Rutledge later left Congress and was captured by the British when Charleston fell in May 1780 and was held for nearly a year. After the war, his finances and businesses flourished and he returned to state politics, and was elected governor of South Carolina, but died at 50 in 1800, before his term ended. YES

–Roger Sherman (Connecticut) A self-educated son of a farmer, he was a prosperous merchant, attorney, and politician, aged 55 at the signing. He would sign three of the central documents in America’s foundation: the Declaration (he was a member of the draft committee), the Articles of Confederation, and the U.S. Constitution. It was at the 1787 convention that Sherman proposed the “Great Compromise” that ended the deadlock between large and small states. He was also a true “Founding Father”– after Carroll (18 children) and Ellery (16 children), Sherman fathered the third most children among the signers -15. A leading Federalist, he served in the House and Senate, where he was serving at his death in 1793 at age 72. NO

–James Smith (Pennsylvania) Another immigrant signer, he was born in Ireland and was around 57 at the signing, another self-taught attorney. Elected to Congress after the July vote, he signed the Declaration. He returned to law practice and state offices before his death in 1806 at about age 87. NO

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

America’s Hidden History, includes tales of “Forgotten Founders”

June 28, 2019

Whatever Became of 56 Signers? (Part 8)

[Part 8 of a blog series that begins here. Note: YES following an entry means the signer enslaved people; NO means he did not.]

…We mutually pledge to each other our Lives, our Fortunes , and our Sacred Honor.

The Grand Flag of the Union, first raised in 1775 and by George Washington in early 1776 in Boston. The Stars and Stripes did not become the “American flag” until June 14, 1777. (Author photo © Kenneth C. Davis)

Minister turned lawyer. Self-taught planters’s sons. A Nay vote. A rare bachelor. And a veiled man. The next six signers:

–Thomas Nelson, Jr. (Virginia) Another son of a wealthy planter. he was a 37 year old merchant-planter at the signing, owner of more than 400 enslaved people. He raised money to supply troops and even commanded militia. Legend has it that he fired a cannon at his own Yorktown mansion during the 1781 siege when told that it was British headquarters. The war cost him financially and he was in ill health, retiring as Virginia’s governor and living on his plantation until his death at 50 in 1789. YES

–William Paca (Maryland) An attorney and wealthy planter’s son, he was 35 at the signing. A patriot leader in somewhat conservative Maryland, he helped bring the state to favor independence at Philadelphia. He raised funds for the war effort and later, as Congressman, worked to support veterans. An advocate of the Constitution, he was later appointed a federal judge by President Washington, and was in that post at his death in 1799 at age 58. YES

Robert Treat Paine (Courtesy: Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston, Massachusetts)

–Robert Treat Paine (Massachusetts) Overshadowed by two Adamses and Hancock from Massachusetts, he was a minister turned attorney, 45 at the signing, best known as one of the prosecutors in the 1770 trial of the British soldiers charged in “Boston Massacre.” His friend and fellow delegate John Adams had served rather successfully as their defender. In 1780, he was among the founders of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, one of the first American groups dedicated to expanding scientific knowledge and learning. After the war, he remained active in Massachusetts politics and was named a state judge by Hancock until his retirement in 1804 due to deafness. He died in 1814 at age 83. NO

–John Penn (North Carolina) A wealthy planter’s son who taught himself to read and write, he was a 36 year old attorney at the signing. He remained in Congress and was one of the signers who also signed the first American constitution, the Articles of Confederation. He retired to private law practice and died in 1788 at age 48. YES

–George Read ( Delaware) Among the conservative delegates, he was a 42 year old lawyer at the time of the signing but had voted against independence on July 2.He served in state offices until ill health forced his resignation. But he returned to Philadelphia to take part in the Constitutional convention and was leading voice for small states’s rights and led the ratification forces in Delaware, the first state to ratify the Constitution. Elected to the Senate, he resigned to take a judgeship in Delaware before his death in 1798 at age 65. YES

Statue of Caesar Rodney on his ride-Rodney Square Wilmington, DE (Public Domain)

–Caesar Rodney (Delaware) Another self educated attorney, son of a planter, he was 47 at the signing. He is best known for an 80 mile ride in a storm to break a deadlock that put Delaware in the independence column –which cost him favor with conservatives in his home state. One of the three bachelor signers (Francis Lee and Thomas Lynch were the others), he remained in the Congress until he became Delaware’s state president. A cancerous growth on his face was untreated and he covered it with a silk veil, worn for a decade before his death in 1784 at age 55. YES