Kenneth C. Davis's Blog, page 49

August 20, 2018

Why Labor Day? Check out this Ted-Ed animated video

“Why do Americans and Canadians Celebrate Labor Day?”

This Ted-Ed animated video explains the history of the holiday and why it still matters today. (Reposted from 9/1/2014)

You can also view it on YouTube:

You can read more about the history and meaning of Labor Day in this piece I wrote for CNN a few years ago:

“The Blood and Sweat Behind Labor Day”

Read more about the period of labor unrest in Don’t Know Much About® History.

Don’t Know Much About History (Revised, Expanded and Updated Edition)

August 8, 2018

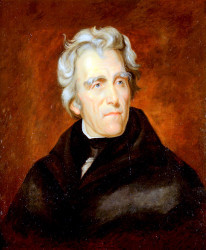

Don’t Know Much About® Andrew Jackson

Imacon Color Scanner

(8/9/2018: Revision of original post of March 15, 2014. Video created and directed by Colin Davis.)

On August 9, 1814, Major General Andrew Jackson signed the Treaty of Fort Jackson ending the Creek War. The agreement provided for the surrender of twenty-three million acres of Creek land to the United States. This vast territory encompassed more than half of present-day Alabama and part of southern Georgia.

Resources from Library of Congress.

Andrew Jackson, the 7th President of the United States, was born on March 15, 1767 on the border of both South and North Carolina (the precise location is uncertain).

When this was last posted, he had fallen from favor and was going to be moved to the back side of the $20 in favor of Harriet Tubman. But with a new president, comes

And Harriet Tubman’s place on the $20 bill is no longer a certainty.

In his day and ever since, Andrew Jackson provoked high emotions and sharp opinions. Thomas Jefferson once called him, “A dangerous man. ”

His predecessor as president, John Quincy Adams, a bitter political rival, said Jackson was,

“A barbarian who could not even write a sentence of grammar and could hardly spell his own name.”

His place and reputation as an Indian fighter began with a somewhat overlooked fight against the Creek nation led by a half-Creek, half-Scot warrior named William Weatherford, or Red Eagle following an attack on an outpost known as Fort Mims north of Mobile, Alabama. Like Pearl Harbor or 9/11, it was an event that shocked the nation. Soon, Red Eagle and his Creek warriors were at war with Andrew Jackson, the Nashville lawyer turned politician, who had no love for the British or Native Americans.

The complete story of the Red Creek War is told in my book A Nation Rising.

You know the name of Andrew Jackson. But you probably don’t know the name William Weatherford. You should. He was a charismatic leader of his people who wanted freedom and to protect his land. Just like “Braveheart,” or William Wallace, of Mel Gibson fame. Only William Weatherford, or Red Eagle, wasn’t fighting a cruel King. He was at war with the United States government. And Andrew Jackson. This video offers a quick overview of Weatherford’s war with Jackson that ultimately led the demise of the Creek nation.

Andrew Jackson died on June 8, 1845. He was surrounded by many of the household servants he had enslaved. He told them:

Tombstone of Alfred Jackson, enslaved servant of Andrew Jackson. (Author photo © 2010)

“I want all to prepare to meet me in heaven….Christ has no respect to color.”

The story of one of those people, Alfred Jackson, is told in my recent book, In the Shadow of Liberty. Alfred Jackson is buried in the garden at the Hermitage, near Andrew Jackson’s gravesite.

August 7, 2018

Who Said It? (8/7/2018)

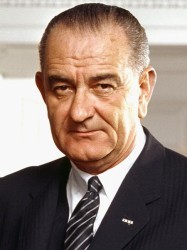

Lyndon B. Johnson, as quoted in Vietnam: A History by Stanley Karnow, regarding the supposed attack on a U.S. Navy vessel off the coast of Vietnam in August 1964.

Even Johnson privately expressed doubts only a few days after the second attack supposedly took place, confiding to an aide, ‘Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.’”

On August 7, 1964, Congress approved a resolution that soon became the legal foundation for Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. (New York Times story)

It came in August 1964 with a brief encounter in the Gulf of Tonkin, the waters off the coast of North Vietnam where the U.S. Navy posted warships loaded with electronic eavesdropping equipment enabling them to monitor North Vietnamese military operations and provide intelligence to CIA-trained South Vietnamese commandos.

Read the entire story of the Tonkin Resolution in this post.

Don’t Know Much About® the Tonkin Resolution

[8/2016 post updated 8/7/2018]

What was the Tonkin Resolution?

Photograph taken from USS Maddox (DD-731) during her engagement with three North Vietnamese motor torpedo boats in the Gulf of Tonkin, 2 August 1964. (Courtesy of the U.S. Naval Historical Cente)r

On August 7, 1964, Congress approved a resolution that soon became the legal foundation for Lyndon B. Johnson’s escalation of the Vietnam War. (New York Times story)

It came in August 1964 with a brief encounter in the Gulf of Tonkin, the waters off the coast of North Vietnam where the U.S. Navy posted warships loaded with electronic eavesdropping equipment enabling them to monitor North Vietnamese military operations and provide intelligence to CIA-trained South Vietnamese commandos. One of these ships, the U.S.S. Maddox was reportedly fired on by gunboats from North Vietnam.

Lyndon B. Johnson (March 1964) Photo: Arnold Newman, White House Press Office

The reported attack came in the midst of LBJ’s 1964 campaign against hawkish Republican Barry Goldwater. President Johnson felt the incident called for a tough response and had the Navy send the Maddox and a second destroyer, the Turner Joy, back into the Gulf of Tonkin. A radar man on the Turner Joy saw some blips, and that boat opened fire. On the Maddox, there were also reports of incoming torpedoes, and the Maddox began to fire. There was never any confirmation that either ship had actually been attacked. Later, the radar blips would be attributed to weather conditions and jittery nerves among the crew.

According to Stanley Karnow’s Vietnam: A History,

“Even Johnson privately expressed doubts only a few days after the second attack supposedly took place, confiding to an aide, ‘Hell, those dumb stupid sailors were just shooting at flying fish.’”

Johnson ordered an air strike against North Vietnam and then called for passage of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution. This legislation gave the president the authority to “take all necessary measures” to repel attacks against U.S. forces and to “prevent further aggression.” The resolution not only gave Johnson the powers he needed to increase American commitment to Vietnam, but allowed him to blunt Goldwater’s accusations that Johnson was “timid before Communism.”

The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution passed the House unanimously after only forty minutes of debate. In the Senate, there were only two voices in opposition. What Congress did not know was that the resolution had been drafted several months before the Tonkin incident took place. In June 1964, on LBJ’s orders, according to journalist-historian Tim Weiner,

“Bill Bundy, the assistant secretary of state for the Far East, brother of the national security adviser, and a veteran CIA analyst, had drawn up a war resolution to be sent to Congress when the moment was ripe.” (Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA, p. 280)

Congress, which has sole constitutional authority to declare war, had handed that power over to Johnson, who was not a bit reluctant to use it. One of the senators who voted against the Tonkin Resolution, Oregon’s Wayne Morse, later said,

“I believe that history will record that we have made a great mistake in subverting and circumventing the Constitution.”

After the vote, Walt Rostow, an adviser to Lyndon Johnson, remarked,

“We don’t know what happened, but it had the desired result.”

In January 1971, Congress repealed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution as popular opinion grew against a continued U.S. military involvement in Vietnam

Since Vietnam, United States military actions have taken place as part of United Nations’ actions, in the context of joint congressional resolutions, or within the confines of the War Powers Resolution (also known as the War Powers Act) that was passed in 1973, over the objections (and veto) of President Richard Nixon.”

The War Powers Resolution came as a direct reaction to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, as Congress sought to avoid another military conflict where it had little input.

“The Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the Limits of Presidential Power” National Constitution Center

In 2005, the National Security Agency (NSA) issued a report reviewing the Tonkin incident in which it said “no attack had happened.” (Weiner, p. 280)

The National Endowment for the Humanities website Edsitement offers teaching resources on Tonkin and the escalation of the Vietnam War.

Read more about Vietnam, LBJ and his administration in Don’t Know Much About® History, Don’t Know Much About® the American Presidents. The Vietnam War and the Tonkin Resolution are also covered in a chapter on the Tet offensive of 1968 in THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR.

Now In paperback THE HIDDEN HISTORY OF AMERICA AT WAR: Untold Tales from Yorktown to Fallujah

July 27, 2018

“Two Societies, One Black, One White”

(Revised post originally published on February 29, 2016)

Once again, it seems valuable to repost this piece about the Kerner Commission, formed fifty-one years ago to address violence in American cities.

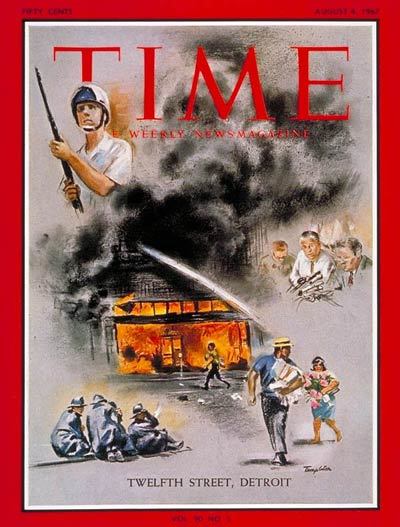

On July 27, 1967, President Lyndon B. Johnson established an 11-member National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders. He was responding to a series of violent outbursts in predominantly black urban neighborhoods in such cities as Detroit and Newark. (New York Times account.)

Time Magazine cover August 4, 1967

On July 29, 1967, President Johnson made remarks about the reasons for the commission:

The civil peace has been shattered in a number of cities. The American people are deeply disturbed. They are baffled and dismayed by the wholesale looting and violence that has occurred both in small towns and in great metropolitan centers.

No society can tolerate massive violence, any more than a body can tolerate massive disease. And we in America shall not tolerate it.

But just saying that does not solve the problem. We need to know the answers, I think, to three basic questions about these riots:

–What happened?

–Why did it happen?

–What can be done to prevent it from happening again and again?

Source:Lyndon B. Johnson: “Remarks Upon Signing Order Establishing the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders.,” July 29, 1967. Online by Gerhard Peters and John T. Woolley, The American Presidency Project.

On Feb. 29, 1968, President Johnson’s National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, later known as the Kerner Commission after its chairman, Governor Otto Kerner, Jr. of Illinois, issued a stark warning:

“Our Nation Is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”

Governor of Illinois Otto Kerner, Jr., meeting with Roy Wilkins (left) and President Lyndon Johnson (right) in the White House. 29 July 1967 Source LBJ Presidential Library

The Committee Report went on to identify a set of “deeply held grievances” that it believed had led to the violence.

Although almost all cities had some sort of formal grievance mechanism for handling citizen complaints, this typically was regarded by Negroes as ineffective and was generally ignored.

Although specific grievances varied from city to city, at least 12 deeply held grievances can be identified and ranked into three levels of relative intensity:

First Level of Intensity

1. Police practices

2. Unemployment and underemployment

3. Inadequate housing

Second Level of Intensity

4. Inadequate education

5. Poor recreation facilities and programs

6. Ineffectiveness of the political structure and grievance mechanisms.

Third Level of Intensity

7. Disrespectful white attitudes

8. Discriminatory administration of justice

9. Inadequacy of federal programs

10. Inadequacy of municipal services

11. Discriminatory consumer and credit practices

12. Inadequate welfare programs

Source: “Our Nation is Moving Toward Two Societies, One Black, One White—Separate and Unequal”: Excerpts from the Kerner Report; American Social History Project / Center for Media and Learning (Graduate Center, CUNY)

and the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University).

Issued half a century ago, the list of grievances reads as if it could have been written last week.

July 26, 2018

Don’t Know Much About Executive Order 9981

[Repost; originally posted 7/26/2013]

This is how a president, who actually served in the military (World War I) dealt with discrimination.

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman issued an Executive Order that ended official discrimination in the United States military.

[image error]

After Truman’s order. the U.S. military was desegregated and integrated units fought in Korea. (Photo: U.S. Army-November 1950)

It is hereby declared to be the policy of the President that there shall be equality of treatment and opportunity for all persons in the armed services without regard to race, color, religion or national origin. This policy shall be put into effect as rapidly as possible, having due regard to the time required to effectuate any necessary changes without impairing efficiency or morale.

Coming in an election year, it was a daring move by Truman, who still needed the support of southern segregationists. It was also a controversial decision that led to the forced retirement of the Secretary of the Army when he refused to desegregate the Army.

As historical documents go, “Executive Order 9981” doesn’t have quite the same ring as “Emancipation Proclamation” or “New Deal.” But when President Harry S. Truman issued this Executive Order, he helped transform the country. This order began the gradual official process of desegregating America’s armed forces, which was a groundbreaking step for the American civil rights movement. (It is worth noting that many of the arguments made at the time against integration of the armed services –unit cohesion, morale of the troops, discipline in the ranks– were also made about the question of homosexuals serving in the military, a policy effectively ended when “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” was overturned in 2011.)

In a Defense Department history of the integration of the Armed Forces, Brigadier General James Collins Jr. wrote in 1980:

The integration of the armed forces was a momentous event in our military and national history…. The experiences in World War II and the postwar pressures generated by the civil rights movement compelled all the services –Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps — to reexamine their traditional practices of segregation. While there were differences in the ways that the services moved toward integration, all were subject to the same demands, fears, and prejudices and had the same need to use their resources in a more rational and economical way. All of them reached the same conclusion: traditional attitudes toward minorities must give way to democratic concepts of civil rights.

Here is the text of the Executive Order 9981 (dated July 26, 1948)

A Chronology of events leading to the Order and more information can be found at the the Truman Library.

July 7, 2018

Don’t Know Much About the 14th Amendment

(The original post of this piece is from July 2010 and was revised in 2015, again in July 2017 and now on June 24, 2018)

“Due Process” and “Equal Protection” for all…

Image Source: Supreme Court of the United States

It seems like a good time to revisit the 14th Amendment in light of the President’s call to deprive immigrants who illegally cross the border of due process rights.

In 1982, the Supreme Court ruled:

“Aliens, even aliens whose presence in this country is unlawful, have long been recognized as ‘persons’ guaranteed due process of law by the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.”

Source: Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Plyer v Doe

As another commentator put it:

In summary, the entire case of illegal aliens being covered by and protected by the Constitution has been settled law for 129 years and rests on one word: ‘person.’ It is the word ‘person’ that connects the dots of ‘due process’ and ‘equal protection’ in the 14th Amendment to the U.S Constitution and it is those five words that make the Constitution of the United States and its 14th amendment the most important political document since the Magna Carta in all world history.

Source: “Yes, Illegal aliens have constitutional rights.” The Hill

THE HISTORY:

On July 9, 1868, the states of Louisiana and South Carolina ratified the 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, providing the necessary three-fourths of the states to adopt this very significant Amendment as part of the law of the land.

One of the “Reconstruction Amendments” ratified in the wake of the Civil War, it had far-reaching consequences in American history, touching on many aspects of public and private life in America — from the schoolroom to the bedroom. And it still does.

The first two sections of the Amendment read as follows.

AMENDMENT XIV Passed by Congress June 13, 1866. Ratified July 9, 1868. Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice-President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age,* and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State. *Changed by section 1 of the 26th amendment.

Its immediate impact was to give citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States,” which included formerly enslaved people. Creating national citizenship that was independent of state citizenship, the 14th Amendment reversed the 1857 Dred Scott decision which denied citizenship to the enslaved.

In addition, the 14th Amendment forbids states from denying any person “life, liberty or property, without due process of law” or to “deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of its laws.”

These clauses, usually referred to as “due process” and “equal protection,” have been involved in some of the most significant decisions in American history. You don’t need to be a Constitutional scholar to understand this Amendment and the profound impact it has had –and continues to have– on every American’s life as well as the rights of non-citizens.

The 14th Amendment has been invoked in such major decisions as Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, which ended segregation of public schools; Roe v. Wade (1973), which disallowed most existing restrictions on abortion; and Loving v. Virginia (1967), which ended race-based restrictions on marriage in America. It also provided the Constitutional authority for many of the most important pieces of civil rights legislation passed in the 1960s. And the 14th Amendment has been central to the same-sex marriage debate. Here is an article from the National Constitution Center on 10 Supreme Court Cases about the 14th Amendment.

And here are other resources on the 14th Amendment from the National Constitution Center’s Interactive Constitution.

Here is a link to more information on the 14th Amendment from the Library of Congress.

July 6, 2018

Who Said It?

Thomas Paine, “The Crisis” (December 23, 1776)

Portrait of Thomas Paine (1792) National Portrait Gallery

THESE are the times that try men’s souls. The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands by it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph. What we obtain too cheap, we esteem too lightly: it is dearness only that gives every thing its value.

Note: Most of these Who Said It posts have focused on the words of American presidents. This quote from Thomas Paine is a shift to quotes from other key figures in American History. Learn more about Thomas Paine’s life at the Thomas Paine Society.

July 5, 2018

More Deadly Than War: The Hidden History of the Spanish Flu and the First World War (Available May 15)

Now available, this book recounts the story of the most deadly epidemic in modern times, the Spanish Flu pandemic, which struck the world 100 years ago during the last months of World War I.

The book and audio versions are available for preorder and links to online sellers can be found here.

Davis (In the Shadow of Liberty) immediately sets the urgent tone of his forthright chronicle, citing staggering statistics: the Spanish Flu pandemic that began in spring 1918 claimed the lives of more than 675,000 Americans in a single year and left a worldwide death toll estimated at 100 million. The author structures his exhaustive account of the origins, transmission, and consequences of the pandemic within the framework of WWI, underscoring the lethal concurrence of these “twin catastrophes.”

Invisible. Incurable. Unstoppable.

From bestselling author Kenneth C. Davis comes a fascinating account of the Spanish influenza pandemic that swept the world from 1918 to 1919.

With 2018 marking the centennial of the worst disease outbreak in modern history, the story of the Spanish flu is more relevant today than ever. This dramatic narrative, told through the stories and voices of the people caught in the deadly maelstrom, explores how this vast, global epidemic was intertwined with the horrors of World War I – and how it could happen again. Complete with photographs, period documents, modern research, and firsthand reports by medical professionals and survivors, this book provides captivating insight into a catastrophe that transformed America in the early twentieth century.

Listen to a sample of the Audio version coming from Penguin Random House Audio.

I hope you will also read my previous book IN THE SHADOW OF LIBERTY.

July 4, 2018

Jefferson’s Version-A few key differences

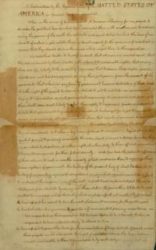

Here is a post I wrote in 2009 after visiting the copy Thomas Jefferson made of his draft version of the Declaration at the New York Public Library:

Last evening, I had a thrilling experience. In a small, darkened room with the feel of a chapel inside the magnificent New York Public Library, I saw Thomas Jefferson’s handwritten copy of his original draft of the Declaration of Independence. For me this was a “Grail Moment.” Setting aside all of Jefferson’s contradictions and human flaws, I found the experience of seeing these words in his own hand exhilarating.

We take them for granted, of course. But Jefferson gave full voice to the idea that we all possess “inalienable rights” –That we are “created equal.” That we have basic rights to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” That governments exist to advance those human rights, and only with the “consent of the governed.”

The document is written on both sides of two pieces of paper. In his careful, flowing script, Jefferson included all of his original wording to show what the Congress in Philadelphia had changed, underscoring words and phrases that had been deleted. Those alterations, Jefferson, thought were “mutilations.” Distressed by the editing, he made these “fair copies” of his original some time after July 4th. (The document on display at the New York Public Library is one of only two known surviving copies.)

Jefferson’s Desk on which he drafted the Declaration (Image: American Museum of History/Smithsonian)

The most startling of these changes is a paragraph about what Jefferson calls “this execrable commerce” — slavery. Jefferson charged –rather ridiculously, of course– that King George III was responsible for the slave trade and was preventing American efforts to restrain that trade. The section was deleted completely. But it is striking to see Jefferson’s bold, block lettering when he describes:

an open market where MEN should be bought & sold

Yes, he was going home to a plantation completely dependent upon slave labor. But he clearly wanted to underscore his belief that slaves were MEN. The contradiction is stunning, troubling, and difficult to resolve.

As the nation approaches its celebration of Independence and the ideals of “Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness,” it is always crucial –and challenging– to remember that with those rights comes responsibility. We have traveled a remarkable road in 233 years (in 2018: 242 years). There is no more powerful symbol of that distance than the fact that an African American has been elected president.

But we still have far to go until we all have secured all of those rights –equality, life, liberty, the pursuit of happiness– for all of the people. Jefferson and his 55 fellow signers pledged their lives, fortunes and “sacred honor” in support of those fundamental human rights. Would we all be willing to say the same?